Overview

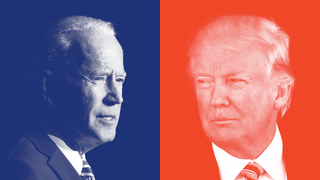

Every US general election carries implications for Australia. But many observers would insist that this time, it’s different, that the trajectories of the United States under a second Trump administration or a Biden administration seem quite different, as do the implications for Australia.

But what is really at stake for Australia? What policy arenas — or elements of politics, the economy, or culture and society of the United States — are likely to be impacted by either election outcome? Among these points of change or continuity, which are of relevance to Australians and Australia’s national interests? How might Australia best respond?

These are the questions addressed in this series of assessments by the researchers of the United States Studies Centre, a collection designed to help frame Australia’s relationship with the United States under either election outcome.

China and the remaking of the American strategic mindset. Irrespective of the election outcome, an enduring legacy of the Trump administration is a resetting of the American strategic mindset: great power rivalry is now the singular external challenge faced by the United States, principally with China and across myriad domains, expanding to non-traditional and emerging vectors of state power. There is no meaningful partisan dispute on this point. Policy modus operandi will differ, perhaps markedly, between a second-term Trump administration and a Biden administration. But the historical significance, high stakes and breadth of the challenge facing the United States is accepted across the American political spectrum.

Australia is an “ally of substance” and can speak accordingly. Australia comes to second Trump term or a Biden administration with impeccable alliance credentials — in no small measure a function of Australia being on the “frontlines” with respect to the China challenge and responding credibly. Few countries enter the Washington post-election environment with as much goodwill, a position of strength that will serve Australia well under either election scenario. This capital should be deployed to ensure Australian voices contribute to the evolution of Indo-Pacific policy in a second Trump administration or to the strategy reviews likely to be undertaken early in a Biden administration.

A goldilocks China policy? If the Obama administration emphasised areas of cooperation with China, and the Trump administration sees itself in strategic competition with China, then a Biden administration will seek to do both.

- Having taken some costly actions with respect to China (tariffs, bans and scrutiny on Chinese investment in particular industries), neither a Trump administration nor a Biden administration will backtrack, at least not rapidly. Even among Trump’s political enemies, there is an acknowledgement that China is a strategic competitor and a different US approach was overdue, that Trump actions have bought the US leverage vis-à-vis China and are important signals of US resolve.

- Climate change is central to Biden policy priorities and frequently cited as a domain in which a productive, cooperative relationship with China is welcome — an obvious point of divergence with the Trump administration.

- Biden promises his China policy will be “more scalpel, less sledgehammer," especially on economic and technological decoupling. Should Biden win, developing and operationalising this nuanced China policy will be contested and delicate work, and will compete with many other domestic and foreign policy challenges. Australia has much at stake and should not — and will not — be a passive bystander.

- Normalising and deepening ties with allies and partners figures prominently in Biden’s foreign policy aspirations but will come to the fore in the Indo-Pacific. Both sides of US politics acknowledge that the magnitude and breadth of the China challenge can only be effectively met in partnership with allies, but this acknowledgement seems more foundational under a Biden administration.

The depth of the public health and economic crises wrought by COVID-19 in the United States suggests that absent a national security crisis, foreign policy and defence will struggle for “above-the-fold” political and public attention in the United States after the election.

Will international affairs struggle for daylight in a crowded US policy agenda? The depth of the public health and economic crises wrought by COVID-19 in the United States suggests that absent a national security crisis, foreign policy and defence will struggle for “above-the-fold” political and public attention in the United States after the election. But should he win, Biden will draw on a deep reservoir of foreign policy and national security talent, experienced with the machinery of government and the cumbersome nature of a presidential transition and already far advanced in their planning. There will be plenty of signals of intent and priorities from a nascent Biden administration with respect to foreign and national security policy. Senate confirmation of senior officials will slow down the implementation of new policy settings.

Several observations follow:

- But a Biden national security team will be eager to reassure allies and partners that notwithstanding the depth of the COVID-19 pandemic — and the usual vagaries accompanying a transition of power — that the ability of the United States to project power and influence is not diminished.

Several observations follow:

- Don’t underestimate the force of inertia. Considerable continuity should be expected with respect to defence and foreign policy in the short term, under either election scenario.

- Burden sharing is here to stay. Capable and committed US allies such as Australia and Japan will continue on their trajectories of more self-reliance in foreign policy and defence in the Indo-Pacific. Policy distraction and overload in the United States, bureaucratic inertia associated with any transition of power and longer-term strains on US defence budgets leave allies such as Australia and Japan with little alternative.

- Early mover advantage? Policy overload and bureaucratic inertia under any election scenario can be parlayed into an opportunity for Australian interests. Australia should continue working with other allies and like-minded partners on elements of collective security in the region, establishing policy facts-on-the-ground and mindsets more aligned to Australia’s national interests, and entrenching Australian points of view ahead of and in anticipation of the position and commitments of a Biden administration.

- In an alliance refresh, what does Australia want? If elected, a Biden administration turns to restoring more conventional relationships with allies — in the context of accepting China and the Indo-Pacific as the greatest strategic challenges faced by the United States — Australia has an opening for moving the United States on long-standing but slow-moving issues in the alliance. Examples include genuine defence industry integration, using the deep and long-standing levels of trust in the bilateral relationship to develop supply chain resilience (e.g., critical materials and frontier technologies), greater presence and influence in both planning for regional contingencies and contributing to US higher-level or longer-range military and strategic planning.

E pluribus duo? Partisan polarisation is a defining characteristic of contemporary American politics. Consider the drivers of this polarisation: deep economic and racial inequality; geographic “sorting” generating de facto partisan segregation, exploited by partisan gerrymanders; political institutions that cede disproportionate power to highly motivated but immoderate voices (non-compulsory turnout, primary elections); a news media landscape disrupted by social media, incentivised to cater to distinct audiences segmented by partisanship and ideology, much like social media itself. None of these are disappearing soon.

- In the shadows — but increasingly less so — and exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and malign foreign actors, conspiratorial thinking and movements have flourished.

- Polarisation drives political and policy distraction in Washington, threatening America's response to public health, security and foreign policy crises. Openness to international trade and investment, alliance commitments, defence spending, defending against foreign interference are all examples of issues that only a few decades ago were relatively immune from partisan rancour in the United States, but of importance and relevance to Australia and its national interests. Australia’s national interests are also squarely implicated should partisan polarisation continue to slow America’s response and recovery from COVID.-19

- Social media and the ubiquity and speed of the internet means there is more cultural, intellectual and social cross-fertilisation from the United States into Australia than ever before. This is overwhelmingly a positive development, with Australian civil society drawing inspiration from and collaborating with American counterparts, in realms too numerous to count.

- But this inspiration and collaboration has less socially desirable facets, with the flourishing of conspiratorial thinking and movements in the United States easily imported into Australia. COVID-19 and its prominence in the US election are amplifying the prominence of opposition to vaccines and public health measures (masks, social distancing, lockdowns) and threats of violence directed against elected political leaders.

Relationship management. Through deft and creative diplomacy and our “frontline” position vis-à-vis China, Australia enjoys a close relationship with a sometimes unpredictable and unconventional Trump administration. But how does Australia navigate Washington under either election outcome?

- Even more unconventional in a second term? Presidencies often mature and even mellow in a second term. But will this be the case under Trump? If Trump wins re-election — again, defying polls, pundits and his many critics — Trump and his advisors will understandably feel validated and emboldened, with foreign policy one of the domains in which that validation is operationalised. “America First” could take on a larger, legacy-defining role in the foreign policy of a second Trump administration, perhaps with more risks for the NATO countries, South Korea and possibly Japan than for Australia. Trump’s palpable fury with China over the COVID-19 pandemic — and a determination to “make China pay” — carries with it some risk of surprise, unilateral actions by the United States against China. US scepticism of multilateral institutions and processes that lie at the heart of the “rules-based international order" will almost surely continue in a second Trump administration.

- A return to convention makes Australia just one of many allies. A Biden administration will seek to renormalise alliance and partner relationships and modes of transacting business in Washington. Other countries that have felt “out in the cold” in Trump’s Washington will compete with Australia for influence with a Biden administration. Australia’s alliance credentials and our “frontline” status with respect to China are tremendous assets here. But risks abound, with NATO partners understandably keen for a post-Trump reset of strategic US priorities and alliance management, along with internal competitions for resources across the US government threatening to distract attention from the Indo-Pacific.

Biden and climate change. A Biden administration will be under intense pressure to see that campaign promises for climate change policy responses are seen through. Biden has said he will return the United States to international climate change fora (e.g., the Paris Climate Accord) and promised a net-zero 2050 target to decarbonise the US electricity sector by 2035 supported by massive investments in clean energy technologies.

- Policy divergence? Biden has pledged to put pressure on other countries to adopt more ambitious targets, using American economic leverage and by integrating climate change initiatives into security and trade policy. This could have significant implications for Australia, which ranks last in the OECD in greenhouse emissions per capita.

The scale of any Biden climate change policy ensemble will depend on whether Democrats also take the US Senate and can work around or reform the Senate’s 60-vote supermajority rule (the filibuster). Absent Senate control, Biden’s ability to move on climate will be limited to executive orders and regulations, all of which will be subject to legal challenges.

Climate change policy could well become a domain in which the United States — at least in appearance, if not in law and policy — vaults from being more sceptical of targets and international agreements than the Australian government to precisely the opposite.

But the ambition to inject climate change considerations into security and trade policy lies more squarely in the purview of the executive branch, with tremendous scope for rule-making and regulations with implications for Australia, say, if the United States regulated international investments in energy-producing or carbon-emitting industries and firms, mandated carbon offsets, or instituted preferred supplier rules or emissions-based duties or tariffs.

Accordingly, climate change policy could well become a domain in which the United States — at least in appearance, if not in law and policy — vaults from being more sceptical of targets and international agreements than the Australian government to precisely the opposite. If Biden is elected, this is a policy domain that will warrant close and constant attention, a potentially new dimension of the US-Australia relationship presenting many opportunities and challenges.

The United States Studies Centre will update these assessments post-election, as the shape of either a second Trump administration or a Biden administration takes shape. The strategic significance of the Indo-Pacific will not change under any case, nor the centrality of Australia’s relationship with the United States as foundational in Australia’s response to the rapid pace of change in the region. Irrespective of the election outcome, the mission of the United States Studies Centre has never been more valuable.

On behalf of the Centre’s researchers, fellows and staff, thank you for your interest in our analysis of America and our insights for Australia.

Simon Jackman

Chief Executive Officer

October 2020

American defence strategy and the Indo-Pacific region

Ashley Townshend

Overview: The United States will seek to bolster conventional deterrence in the Indo-Pacific — a task fraught by strained defence budgets and disagreements within the US defence establishment over how to reorient the military for great power competition with China.

Biden contrasts with Trump: A Biden administration will likely pursue a more multilateral approach to strategic competition. A second Trump term is likely to exacerbate frictions between Washington and Indo-Pacific allies on burden-sharing and its zero-sum approach to competition with China.

What Australia should do

- Regardless of who wins the election: Australia should continue to actively contribute to a strategy of collective defence and the maintenance of a stable Indo-Pacific order, and work with like-minded regional partners to offset shortfalls in US military capacity.

- During a Biden administration, Australia should: Develop mechanisms for combined contingency planning, accelerate defence industry integration and gain greater insight and input into US military and strategic plans in the region.

- During a second Trump term, Australia should: Look to build common ground on China policy among Washington and its allies, while seeking greater US investment in Australian defence infrastructure.

Long-term trends

Owing to the enduring nature of the challenges and constraints facing US defence strategy in the Indo-Pacific, there will be significant areas of continuity and overlap no matter who wins the 2020 election. Three are likely to stand out, with mixed implications for Australia.

First, the Indo-Pacific will remain the US Department of Defense’s declared “priority theater.”1 Given the strong bipartisan and bureaucratic support for the Pentagon’s 2018 National Strategy (NDS), this should come as no surprise. The NDS issued a clarion call for the United States to prioritise “inter-state strategic competition” with China ahead of other global security commitments, setting in train a series of renewed efforts to wind-down military operations in the Middle East, bolster deterrence by denial in the Indo-Pacific, and invest more in advanced research and emerging capabilities to maintain the United States’ eroding military-technological edge.2

This agenda is set to continue. Leading Biden advisors, like Michèle Flournoy and Ely Ratner, have strongly endorsed the NDS framework and its core focus on re-establishing conventional deterrence vis-à-vis an assertive China.3 The Democratic Party as a whole, and Joe Biden specifically, publicly support a Middle East drawdown and an end to the United States’ “forever wars,” a platform that is at least partly motivated by a recognition that the Indo-Pacific is the strategically more important region.4 While the Trump administration has been rightly criticised for failing to sufficiently advance certain NDS objectives in the Indo-Pacific — such as bolstering the military’s forward posture and operations designed to blunt Chinese aggression — the Pentagon’s greater focus on this theatre will likely endure.5

The National Defense Strategy issued a clarion call for the United States to prioritise “inter-state strategic competition” with China ahead of other global security commitments, setting in train a series of renewed efforts to wind-down military operations in the Middle East, bolster deterrence by denial in the Indo-Pacific, and invest more in advanced research and emerging capabilities to maintain the United States’ eroding military-technological edge.

Second, the ability of the next administration to implement this Indo-Pacific agenda will be complicated by disagreements within the Department of Defense over how best to prepare the armed forces for strengthening deterrence regarding China. There is a broad consensus in favour of the NDS’ layered approach to conventional deterrence by denial.6 But the relative importance placed on shaping the battlespace, blunting potential attacks and winning a major power war — and what these distinct priorities require by way of short and long-term investments in capabilities and infrastructure — is subject to considerable bureaucratic rivalry.

The United States’ military services — its Army, Navy, Marine Corps, Air Force and Coast Guard — are now primarily focused on retooling their inventories for high-intensity, state-on-state conflict. On the other hand, US Indo-Pacific Command — which is responsible for the regional application of military force and receives its personnel and materiel from the services — must prioritise the day-to-day requirements of shaping the battlespace, countering low-intensity coercion and maintaining ready forces and critical enablers, like infrastructure and munitions stocks, for immediate use. There are also broader non-partisan disagreements across the defence establishment over the right balance between legacy and advanced systems, the optimum size of the force and specific platforms like ships, and the speed and scale with which the US military should invest, experiment and field next-generation capabilities.7

Some of these tensions will be addressed in favour of Indo-Pacific Command by the establishment of a Pacific Deterrence Initiative (PDI), which enjoys bicameral and bipartisan support in Congress.8 This bill is intended to strengthen the Command’s lethality, posture and capacity for operational experimentation and enhanced engagement with allies and partners.9 Indeed, the PDI is likely to be expanded in the next presidential term owing to strong congressional support. But with funding for this initiative expected to come in around US$300 million in 2021 — compared to US$4.5 billion for the Pentagon’s European equivalent — it will not inoculate either administration from facing hard choices on NDS implementation in the Indo-Pacific.

Finally, the next administration will face static or, more likely, falling defence budgets, compounded by massive fiscal pressures. This means that the three to five per cent real annual growth needed to resource the NDS will not be achieved, leading to billowing strategy-resource shortfalls and increasingly difficult choices about global strategic priorities.10

The budget issue is both structural and political. Although congressional Republicans are more bullish in calling for high defence budgets, the Trump administration has only achieved three to five per cent real growth in the defence budget once and is now presiding over a two per cent real decline in the 2021 budget.11 This is partially due to a deal between congressional Republicans and Democrats in 2019, which rounded out ten years of spending caps.12 More importantly, it reflects the reality of the United States’ rising deficit which, even before COVID-19, was projected to reach US$1 trillion in 2020 and average US$1.3 trillion over the next decade — a forecast that led Defense Secretary Mark Esper to conclude in February that the Pentagon’s budget would remain stagnant in the near-term.13 Now, following trillions of dollars in COVID-19 stimulus and lost revenue, the deficit is likely to reach 98 per cent of GDP by the end of 2020, exceeding the post-Second World War record of 106 per cent of GDP by 2023 and projected to rise to 2.5 times GDP by 2050.14

The next administration will face static or, more likely, falling defence budgets, compounded by massive fiscal pressures. This means that the three to five per cent real annual growth needed to resource the NDS will not be achieved, leading to billowing strategy-resource shortfalls and increasingly difficult choices about global strategic priorities.

These deficit forecasts are already triggering bipartisan concerns about the national debt and a return to the politics of austerity, which could lead to renewed defence spending caps, particularly if different parties control Congress and the White House.15 These structural constraints on future Pentagon spending will be a major challenge whoever wins the election, requiring US global defence priorities to be negotiated down or military and operational risk to be spread more widely.

Together, these three trends shaping America’s Indo-Pacific defence strategy reinforce the need for Australia to play a more active role in contributing to the maintenance of a stable regional order.16 While Canberra will welcome ongoing prioritisation of the Indo-Pacific as the United States’ core strategic focus, it should be under no illusions that the next administration will be able to quickly, easily or substantially deepen the US military’s strategic footprint in this part of the world.

Changes in US Indo-Pacific posture and the fielding of new weapons systems have typically played out over presidential terms, not calendar years. At the margins, more emphasis on rapid innovation, experimentation and fielding of new capabilities — as the US Air Force is exploring — or increased investment in munitions, fuel, military infrastructure and operational funds through the PDI are possible and hold promise for Australian involvement and collaboration.17 But the combination of rising budgetary pressure and the need to make difficult trade-offs — on both the scope of the NDS and how to realise its Indo-Pacific deterrence objectives — suggests a slow rate of change.

To advance Australia’s interests in upholding collective deterrence and defence in this context, Canberra will need a more direct stake in the next administration’s approach to Indo-Pacific military strategy. With other like-minded partners, Australia should seek to shape US posture and spending decisions in line with regional interests and prospective contributions.18

Blue book

What changes under Biden

A Biden administration will be far more consistent and collectively minded in working with US allies and partners, with the restoration of the “liberal international order” a likely hallmark of Biden foreign policy.19 This will be welcomed by Australia and other Indo-Pacific nations that are increasingly alarmed by President Trump’s aggressive transactionalism. A Biden administration will not mean an end — or even a decline — to US efforts to boost burden-sharing by allies and partners. But Biden and his team are likely to bring a greater willingness to accommodate differences in interests, threat perceptions and contributions to collective action than has recently been the case.20

One reason for this is that Biden’s national security team have a multidimensional view of the role of America’s allies and partners. Potential administration appointees such as Jake Sullivan, Abraham Denmark and Mira Rapp-Hooper have argued that allies and partners — particularly close and capable ones like Australia — must be empowered as regional order enhancers.21 This growing role for allies is consistent with Australia’s expanding foreign and defence policy agenda and may make Biden’s team a more natural partner for implementing and building on this year’s ambitious Australia-US Ministerial Consultations (AUSMIN) agenda.22

A Biden administration will likely seek focused contributions from Australia to deterrence and security cooperation in the Indo-Pacific. According to Michèle Flournoy — widely expected to be Secretary of Defence under a Biden administration —“the United States should work closely with its allies and partners to make a clear-eyed assessment of what each country can contribute to stabilizing the region and deterring [China’s] increasingly aggressive behaviour.”23 This could include new posture arrangements, enhanced operational presence, cooperation on advanced long-range strike and a more multilateral model for undertaking intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance, anti-submarine warfare and special operations activities.24 Crucially, such a collective approach to defending the regional order is needed to offset the United States’ declining relative capacity and is anticipated by Canberra’s 2020 Defence Strategic Update, designed to see Australia contribute more independently to shared deterrence objectives.25

A Biden administration will not mean an end — or even a decline — to US efforts to boost burden-sharing by allies and partners. But Biden and his team are likely to bring a greater willingness to accommodate differences in interests, threat perceptions and contributions to collective action than has recently been the case.

Two possible concerns for Australia in a Biden defence strategy stand out. First, Democratic Party preferences for lower defence spending will make it harder for the Pentagon to service its Indo-Pacific goals. Biden, to be fair, has a deep appreciation for the military and says that budget cuts are not inevitable.26 And while some congressional Democrats are very vocal in calling for major cuts to the defence budget — for reasons of pandemic relief, austerity or “guns versus butter” concerns — it is unlikely a Biden administration will heed calls for a ten per cent reduction as progressives have proposed.27 Still, with domestic rebuilding the top priority for most Democrats, Biden will face greater partisan pressure than Trump to reduce military spending, especially if Democrats take the Senate, with some predicting a five per cent cut during his administration.28

Second, a Biden defence strategy could become overly global and ideological in ways that are unhelpful to Australia. There is a strong trans-Atlantic orientation in Biden’s foreign policy team — focused on prioritising NATO and standing up to Russia — and a deeply-held belief that restoring the liberal international order requires America’s global promotion of democratic values.29 These sentiments stand behind Biden’s promises to “reinvent the US alliance system with a democratic underpinning” and to “strengthen the coalition of democracies that stand with [America].30 Both are noble ideas that Australia in many ways supports, particularly where strengthening good governance, setting technology norms, defending free trade and similar issues are concerned. But they have the potential to distract a Biden administration from the Indo-Pacific. An expansive liberal order restoration agenda may frustrate Pentagon efforts to reduce its military footprint in Europe and lower priority regions. Placing human rights at the heart of US foreign policy risks alienating strategically like-minded, but illiberal, Indo-Pacific nations.31 While these are not entirely zero-sum issues, they are difficult to balance in terms of resources and foreign policy bandwidth.

What Australia should do

Australia should reinforce the urgency of Indo-Pacific defence requirements as a priority for a Biden administration. Canberra should leverage Biden’s preference for a multidimensional and multilateral approach to strategic competition to carve out a larger role for Australia in setting and contributing to regional security policy. A more explicit strategy of collective defence — to deter a more assertive China — will require Washington and Canberra to address thorny questions of political and operational risk head-on. To advance this strategy, Australia should propose new mechanisms for combined contingency planning, push for genuine two-way defence industry integration and seek to gain insight and input into US military and strategic planning at earlier stages than is currently the case.32 Australia should pursue these objectives as part of ongoing efforts to transform the Australia-US alliance into a vehicle for collective defence and for strengthening each country’s contribution to maintaining regional order.

Red book

What happens under Trump

Donald Trump’s re-election likely intensifies two trends in US Indo-Pacific defence strategy. First, the president’s scepticism towards alliances will likely increase, leading to bitter burden-sharing negotiations and impeding efforts to forge a collective regional strategy. Having already soured alliance goodwill by seeking a five-fold increase in host-country payments to keep US troops in South Korea and Japan, a re-elected Trump will hold an emboldened position to finish these negotiations on his terms and withdraw some US forces.33 Trump could initiate new quarrels with other allies and partners, thereby complicating the Pentagon’s efforts to advance defence cooperation, combined exercises, and posture changes. This would exacerbate the decline of regional perceptions of US reliability, which is still reeling from Trump’s unilateral imposition of tariffs (on many nations), sanctions (on China) and abandonment of the Trans-Pacific Partnership.34 With regional public attitudes towards the United States at record lows,35 support for the US alliance system may begin to fray — undermining Australia’s interests in a robust and networked security order.

Canberra should use the Pentagon’s global force posture review and bilateral posture working group to attract further US investment in Australian defence infrastructure, an issue Congress and the Trump administration have recently supported.

Second, the Trump administration’s increasingly zero-sum approach towards competition with China is likely to continue in a second term, unnerving Indo-Pacific allies and partners instead of building a unified position through policy compromise. This is particularly true in Southeast Asia where the United States’ divisive rhetoric on everything from technology competition and human rights to economic decoupling is creating friction with prospective balancers.36 To be sure, many Indo-Pacific countries privately welcome the administration’s tough stance on China, which they view as a clear-eyed antidote to Obama-era vacillation.37 But rather than building on this sentiment by offering stable and collaborative stewardship on China strategy, the administration has generally sought to force choices on issues like 5G and infrastructure without offering alternatives.38 This approach will continue to impede the development of collective strategy in the Indo-Pacific.

What Australia should do

Australia should continue to identify areas for China policy coordination that can build common ground between the United States and key regional partners. Although there are some encouraging signs in the administration’s approach to supporting Southeast Asian states in the South China Sea — where Washington has clarified its position on the illegality of Chinese claims — it is unclear if similarly well-coordinated initiatives are in train.39 Building on this year’s AUSMIN, US-Australian and regional efforts on health security, pandemic recovery, disinformation and cyber-resilience hold promise.40 Furthermore, Canberra should use the Pentagon’s global force posture review and bilateral posture working group to attract further US investment in Australian defence infrastructure, an issue Congress and the Trump administration have recently supported.41

An Australian view of US policy toward China

Dr John Lee

Overview: The next administration will seek to find ways to apply further economic pressure on China and achieve greater ‘economic distance’ on US rather than Chinese terms.

Biden contrasts with Trump: Trump seeks the most robust coalitions of the willing to advance this agenda or continue to go it alone in many circumstances. In contrast, Biden wants support from as broad a group of advanced economies as possible.

What Australia should do

Regardless of who wins the election: The United States needs to reassert institutional and collective leadership. The key for Australia is not merely to participate in institutions but to compete through them and reshape them in accordance to Australian interests and values where possible.

During a Biden administration: Biden will want to explore institutional approaches to change Chinese behaviour or punish Beijing. Canberra should get in early to suggest approaches that have sensible institutional landing points, and which serve Australian interests and those of those economies that largely abide by international rules.

During a second Trump term, Australia should: Suggest economic offensive policies that have less market or price distorting effects, thereby lowering the unintended or collateral damage to other economies.

Long-term trends

President Trump has both rare achievements and failures when it comes to foreign policy. He has unsettled the nerves of US allies and friends. On the other hand, Trump has changed conversations, perceptions and, ultimately, policy — especially towards China — more than any other administration for generations. Whereas previous administrations dithered and demurred on this issue, Trump’s high tolerance for disruption, risk and antagonism has done more to alter Beijing’s calculations than any other president this century.

Balancing and countering China is now firmly entrenched as the centrepiece of US Indo-Pacific policy — as is the need to take risks to reverse negative trends or else modify Chinese behaviour and calculation. While many of Biden’s advisors have long been alert to the need for the United States to pursue a more proactive stance vis-à-vis China, Biden was slower to accept this call.

This is no longer true — no small thanks to Trump. Biden largely stakes his foreign policy credentials on who will have the more effective China policy. It is for this reason that this brief on the implications for Australia is framed around how the next administration will pursue Indo-Pacific policy, and China-policy, in particular.

Blue book

What changes under Biden

Biden’s team has put forward what they call advancing a favourable ‘competitive coexistence’ with China in strategic, political, economic, and technological contexts. As with all challenges, clues to their policy direction are found in the most ardent criticisms levelled against President Trump.

First, Biden argues that Trump has alienated or ignored allies. As a contrast, Biden considers that alliances offer the United States enduring and decisive advantages not enjoyed by China and promises to be more consultative with traditional allies and partners.

Biden considers that alliances offer the United States enduring and decisive advantages not enjoyed by China and promises to be more consultative with traditional allies and partners.

Second, and in addition to the off-putting framing of a Trump White House focused on ‘America First,' Biden believes that the United States is vacating international responsibilities and leadership by failing to understand the importance of preserving and exercising influence within institutions and regimes, such as the World Trade Organization (WTO), World Health Organization (WHO), and the East Asia Summit. Meanwhile, China has ramped up efforts to increase its presence and influence in regional and global institutions.

Third, Biden believes that Trump’s economic war against China was poorly thought through, reactionary and frequently self-defeating. Biden believes Trump’s approach has been distressing and disruptive for economic partners, having achieved only transient gains for the United States at best while creating further opportunities for China to exercise economic and institutional leadership.

Fourth, Biden believes the United States has ceded moral leadership through the president’s alleged disinterest in human rights, apparent affinity with authoritarian leaders, and disregard of transnational issues such as climate change. There is also the broader domestic criticism that Trump has poor respect for domestic institutions and laws which degrades the country’s moral standing in the world.

a. Personal dynamics and diplomacy with a Biden administration

Paradoxically, Trump’s unorthodox leadership style has worked to the Australian government’s advantage when it comes to attaining meaningful access to the White House relative to other allied and friendly governments. While most governments, such as those in Seoul and Singapore, continue to struggle to come to grips with the current administration, Canberra (and Tokyo) found a way to focus on the positive aspects of Trump’s preparedness to disrupt and take risks, and manage the negative aspects of these same presidential characteristics.

A Biden administration will be far more orthodox in style and process. This means that Canberra will again be competing with many other allied and friendly nations for privileged access and influence on an even playing field.

Moreover, Biden will gather an experienced group of principals and advisors around him who will be well-known to many officials in the region. Biden and his appointees will have well-developed policy views and are less likely to feel the need to seek guidance from Australia in the manner of the Trump administration when the latter came to power in 2017.

The downside is that it might be more difficult for Canberra to acquire and accumulate influence in Washington under Biden than it has been under Trump.

b. The danger of softer temperaments and the seeking of allied consensus

It is often the case that the greater obstacle to strategic ambition, courage, and resourcefulness on the part of allies such as Australia is less that US power is declining in relative terms than the doubting of American resolve and decisiveness. Australians welcomed Obama’s ‘pivot’ or ‘rebalance’ to Asia but lingering doubts about the then president’s determination and willingness to compete and confront sapped the courage of allies, causing the latter to largely hedge rather than balance or counter Chinese actions.

In an environment of deepening strategic competition with China, Biden’s more risk-averse and calmer (i.e., less disruptive) temperament and instincts might be a blessing but possibly a problem.

Furthermore, Trump’s abrasive treatment of allies and partners has been worrisome but has had the effect of persuading some of these, such as Australia and Japan to accept more responsibility and share of the security burden than a softer administration might have managed to coax. Indeed, those countries becoming more serious about countering China, like India, prefer a difficult but confrontational administration to an amicable but meek one. An administration with the latter characteristics is more likely to entice regional countries to hedge, free ride or remain on the sidelines rather than accept difficult and controversial burdens.

The momentum developed behind giving genuine substance to the Quad (between the United States, Japan, India and Australia), the trilateral cooperation between the United States, Japan and Australia in the Pacific, initiatives such as securing critical minerals, and aligning 5G and other technological policies are all controversial policies in China’s eyes and have been driven by the proactive countries in the Indo-Pacific.

It is a sensitive discussion regarding a Biden administration which makes much of the need to work with allies and partners and bring them along. It is a noble sentiment and gesture. But far more important than seeking the broadest possible agreement or consensus amongst allies and partners is the United States prioritising those prepared to absorb risks and do the heavy lifting — even at the risk of leaving others behind.

c. Competing for influence in institutions and crafting institutional responses and solutions

Trump’s poor understanding of the role of institutions in preserving and enhancing US power and influence and the importance of institutional solutions to problems to lock in gains (and defray risks or losses) is one of the most serious shortcomings in the president’s world view. Biden does not suffer that same ignorance and will be far superior to Trump in this regard.

Under Biden, there will be a high appetite for quickly crafting together a strategy to revive US presence and influence in key regional and global institutions. A Biden administration will want to outline: which institutions, why it is necessary, how to retake the initiative, and cooperation with allies such as Australia. Furthermore, Biden is far more likely to emphasise the importance of institutional outcomes to problems.

Climate change — walk and chew gum

In stark contrast to Trump, Biden’s emphasis will be on responding to climate change, domestically and internationally. Australia will have mixed feelings given the approach of the last Democratic president.

Under Biden, it is critical that the current Australian Government is as desperate as the Turnbull government was in 2017 in scrambling to lay the groundwork for access and influence in Washington before other countries attempt to do the same.

In prioritising a legacy producing global agreement on climate change — the Paris Climate Accord — Obama de-emphasised confrontation with China over strategic, economic, and human rights issues. That secured an agreement but was one which placed few burdens on Chinese carbon emissions, the largest emitter by a considerable margin. Obama’s wiliness to soften the US stance on other issues also seemed to embolden China to assertively pursue other objectives at America’s — and Australia’s — expense.

One suspects Canberra will also prefer that a Biden administration treat the lowering of carbon emissions as an economic and technological policy challenge — maintaining a practical agnosticism to global energy mix — rather than approach it as an ideological crusade to promote implausible renewable causes and proscribe even the highly efficient use of fossil fuels.

What Australia should do

It is important that the Australian Government not assume its familiarity with Biden and his appointees will equate to influence and access. Under Biden, it is critical that the current Australian Government is as desperate as the Turnbull government was in 2017 in scrambling to lay the groundwork for access and influence in Washington before other countries attempt to do the same.

Australia has accumulated standing in our willingness to give voice and/or action to fraught issues, such as China’s illegitimate gaming of the global economic system, the weaknesses of the WHO, and Beijing’s unhealthy sway over its leadership. A Biden administration will welcome Australian views of institutional solutions, including reforming the WHO and WTO or cobbling together an alternative regime in areas such as intellectual property protections, a renewed US influence in regional organisations such as the key ASEAN sponsored regimes. There will be an immediate and immense opportunity for Canberra to play an outsized role in setting the American institutional agenda in the early months of 2021.

The overwhelming evidence is that China will always prioritise its economic objectives over climate change responsibilities despite Beijing’s earnest rhetoric on the latter issue. Australia will do well to remind an incoming Biden administration of that reality.

Red book

What happens under Trump

By now, Australia is familiar with the opportunities and challenges of a Trump administration and making the best of it. This is not the same as being comfortable.

With respect to strategic objectives, military posture, and improving interoperability of US and allied forces, there is broad agreement and the ‘to do’ list is well established.

One area of high concern remains Trump’s economic offensive against China — this will undoubtedly accelerate in scope and depth under a second Trump term. The weaponisation of market access, capital denial, technology/know-how denial and even restrictions on US dollar transactions by Chinese entities will be expanded.

Trump’s high tolerance for disruption, risk and antagonism has done more to alter Beijing’s calculations than any other president this century.

Although Canberra agrees with many of the economic accusations levelled against China and the need for the United States to lead measures against Beijing’s activities, Trump’s approach generates high anxiety for these reasons:

- The use of economic weapons and other forms of economic retaliation against China occurs with minimal consultation of or warning given to other countries. Similarly, Australia is largely in the dark about the intended pace and nature of escalation.

- Economic punishment of and retaliation against China is seen largely as a bilateral issue to achieve a better outcome for the United States. Less thought is given to collateral damage inflicted on other economies and there is little interest in embedding outcomes that would benefit Australia and other economies.

What Australia should do

As a response, some priorities might include:

- Improving key diplomat access in Washington DC: Australia’s formal and/or informal access to key individuals in the US Trade Representative agency and the White House’s Trade and Manufacturing Policy team is a little underdone given its excellent access in other areas and the outsized importance of these entities in driving US economic policy toward China.

- Strengthening economic intelligence: Through improved access, Australia may be in a better position to understand the intended outcome of certain offensive economic policies against China — and be in a better position to assess whether Canberra should support it or remain on the sidelines. It might also give Canberra the opportunity to push for desirable institutional outcomes or landing points that the Trump administration could agree with.

- Promote from a superior position: Australia might also be in a better position to suggest economic offensive policies that have less market or price distorting effects, thereby lowering the unintended or collateral damage to other economies. For example, the United States is accumulating a list of infringing Chinese firms which may be targeted by denying crucial technologies or restricting their participation in US dollar transactions. An additional categorisation of targeted firms should consider the extent to which sanctions against these firms would have secondary disruptive ramifications for non-Chinese firms, sectors, and regional supply chains. If the intention is to restrict the presence of Chinese firms in advanced markets, other additional categorisations could include the extent to which there are non-Chinese alternatives to that firm from trusted economies.

Finally, Trump’s disinterest in institutions is a serious problem for US leadership and power — and therefore a problem for Australia. Having said that, all voices should not be considered of equal value or weight. The danger of Trump de-emphasising multilateral institutions should not blind Australians to the perils of passively allowing these institutions (many of which are filled with entities hostile to US and Australian interests and values), shape or bind our important decisions.

The key is to convince the administration that the objective is not merely to participate in institutions but to compete through them and reshape them in accordance with our interests and values where possible. That pitch must be tailored to the administration, but the objective ought to remain the same.

An American view of US policy toward China

Dr Charles Edel

Overview: American attitudes toward China are hardening and Democrats and Republicans will support policies that enhance American competitiveness and push back on Beijing’s more concerning activities.

Biden contrasts with Trump: In a second Trump term, Trump will become more unilateral in his actions and less constrained in his impulses. A Biden administration will work to place allies and partners at the centre of US foreign policy.

What Australia should do

Regardless of who wins the election: Prepare for several policy adjustments from either electoral outcome. It should also prepare to discuss where Australia and the United States are moving in sync, where they are working at cross-purposes, and where joint efforts can expand productively.42

During a Biden administration, Australia should: Prepare for the United States to return to international fora, emphasise values and human rights, and increase technological and economic policy coordination with allies. Australia should reinforce the administrations’ predilection for alliances by early demonstrations of support for the alliance.

During a second Trump term, Australia should: Continue identifying areas of shared interest with the US and then use existing mechanisms to pursue joint goals. Be prepared for a United States increasingly less committed to multilateralism and a White House disinterested in global leadership in defending democracy.

Long-term trends

The relationship between Washington and Beijing is increasingly characterised by competition across nearly every field — economic, military, technological, institutional and, even, ideological. Competition is unlikely to abate and will likely intensify as modifying factors — such as economic interdependence — become less significant drivers of the relationship.

There is a palpable sense of anger in the United States towards the Chinese Government. This has been growing for a while, but recent polling shows hardening attitudes toward China on most issues. Nearly three-quarters of Americans (73 per cent) now say they have an unfavourable view of China,43 and more than 60 per cent believe that the US should take steps to hold China accountable for its handling of the coronavirus and for exploiting US trade policies.44 And, while Democrats and Republicans express different levels of concern about China’s rise, majorities across party lines favour sanctioning Chinese officials for human rights abuses, prohibiting the sale of sensitive high-tech products to China, and prohibiting Chinese technology firms from building communication networks in the United States.45

These attitudes will help support the belief that US policy needs to become more competitive towards China and further strengthen relationships with traditional allies. Recent actions by the Congress bear that out, with legislation moving forward to sanction Chinese officials for the government’s ongoing genocide in Xinjiang, strengthen the United States’ military capabilities in Asia, and significantly boost investment into research, development, and manufacturing of key technology.46 But, as much as popular attitudes and congressional legislation matter, presidential attitudes matter more in the creation of foreign policy. Both Trump and Biden support a sharper approach to dealing with Beijing, but the nature of US competition will shift considerably based on who is elected president in November.

Biden and Trump hold vastly different views on the United States’ role in the world and differ in their objectives, priorities, and preferred strategies. As such, the range of issues and the types of challenges for traditional allies like Australia will differ greatly based on the next occupant of the White House. Nevertheless, Canberra should be prepared for several policy adjustments from either a second Trump term or a first Biden term.

First, there will be significant turnover in the senior ranks of the US foreign policy establishment — either because of replacements in a second Trump term or new appointments in a Biden administration — and Canberra, therefore, should expect to encounter a significant number of new faces over the next several years.

Second, Canberra also should expect more focus on the US-Australia alliance, regardless of who wins. Under either Biden or Trump, there will continue to be intense US interest in Australia’s experiences dealing with foreign interference and economic coercion. There will also be a push for closer collaboration with Australia around technological innovation, supply chain diversification, and regional defence strategy. Canberra should prepare for discussions of where Australia and the United States are moving in sync, where they are working at cross-purposes, and where joint efforts can expand productively.47

There will be significant turnover in the senior ranks of the US foreign policy establishment — either because of replacements in a second Trump term or new appointments in a Biden administration — and Canberra, therefore, should expect to encounter a significant number of new faces over the next several years.

In the context of the United States’ defence policy, Canberra can anticipate two trends — particularly as it relates to Asia. The first is that the balance of power in Asia will continue to tilt towards China in several important areas. The second is that the economic effects of the coronavirus pandemic will intensify downward pressure on the defence budgets of the United States and other nations. Taken together, Australia should anticipate shifts in US defence policy towards a more distributed, more lethal, and less conventional force structure. Such a shift, already underway, is likely to accelerate over the next several years, will carry implications for how the United States’ allies and partners think about, structure, place, and pay for their own armed forces.

Additionally, it seems clear that the further decoupling of the Chinese and American economies will take place under either a Biden or Trump administration, though the depth, breadth, and pace of decoupling will vary based on who is elected.

Finally, there may be some US-China cooperation on particular issues, though those issues will differ based on who occupies the White House and the composition of the new Congress.

Fundamentally, strategic competition between the United States and China will continue regardless of who is elected in November. However, there are a number of variables beyond the election that will also play a role in shaping US policy and the US approach, such as the new Congress, the willingness of allies (such as Australia and Japan) to shoulder a greater role in their own and regional defence, and perhaps most of all, China’s actions and responses to increasingly global concern about its activities.

Blue book

What changes under Biden

Under a Biden administration, a priority will be to reverse moves seen as harming US interests in Asia. Biden has made clear that as China has become more domestically repressive and externally aggressive, the United States will respond not by turning back the clock to an earlier era of engagement, but by better positioning the country to respond to the comprehensive set of challenges that China poses. This has both domestic and foreign policy components.

These will likely include a major shift in tone and rhetoric, a recommitment to multilateral engagement, a renewed focus on Southeast Asia, and a major push to place traditional allies at the centre of US foreign policy. While there will be a drive to identify limited areas of cooperation with China, a certain amount of decoupling of the Chinese and US economies will continue. China policy would likely become a subset of Asia policy and framed more around how best to defend and strengthen democratic institutions and governments than it would be around changing China. Human rights and democracy support would be high on the agenda, as would be boosting the budgets for diplomacy, aid, and development finance. There would be greater investments into technology, R&D, and education in order to ensure China does not surpass the US in cutting-edge technologies. In concrete terms, a Biden administration will likely focus on policies designed to secure technological advantage, strengthen economic resilience by building trusted supply chains, reinvigorate diplomacy, combat illiberal ideologies, promote an open information environment, enhance military deterrence, build greater asymmetric capabilities, and disperse US forces in Asia.

Under Biden, Canberra can expect outreach, discussion, and potential collaboration from Washington on export controls, screening of inbound foreign investment, technological standard-setting, and guidelines governing how research collaboration is overseen.

Within Democratic circles, there remain ongoing debates about trade policy, North Korea, and the size and shape of the defence budget. For all the areas of broad consensus among Democrats, there are also areas of disagreement, churn and ongoing debate. There is an ongoing debate between centrists and progressives that range across the board — from whether or not the United States should maintain military dominance (or, even presence) in Asia, to whether or not values and democracy support have a place in US foreign policy, to whether a more accommodationist approach would work with Xi Jinping’s China. There is debate about whether the primary competition between China and the United States resides primarily in the military realm or in the economic and ideational space, and subsequently which set of policies — and more importantly, budgetary allocation of resources — should receive priority. Finally, there is a broader debate not about whether to compete, but how to sequence competition and cooperation.48 That is, does competition from “situations of strength” require deferring more cooperative policies, or are certain crises — including those relating to global health, economic and climate change — so dire that competition needs to be moderated, or bypassed in these areas. Here, the debate is not over whether competition or cooperation are the better strategies for the United States, but rather how to compete smarter and in what sequence.

What Australia should do

A Biden administration will likely be more selective and strategic in its approach to decoupling with China. Selective decoupling is especially likely to concentrate around critical infrastructure and defence-related industries and research. As this occurs, Canberra can expect outreach, discussion, and potential collaboration from Washington on export controls, screening of inbound foreign investment, technological standard-setting, and guidelines governing how research collaboration is overseen.

Under Biden, the inclination for a more coordinated and multi-lateral response to China will likely replace unilateral and non-coordinated approaches, increasing the necessity of synchronising policy.

In areas of cooperation, a Biden administration will likely attempt to work with China on combating climate change and coordinating on global health challenges, especially in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic. Neither of these, however, are likely to come at the expense of investing in American competitiveness.

Australia should prepare for a return of the United States to international fora, greater emphasis on values and human rights, and an increased push for coordinating technological and economic policies between the United States and its allies. It should also prepare for climate policy to take on a much greater role in a Biden administration, Southeast Asia to occupy a more central focus in America’s Asia policy, and Washington to likely commit more resources to its diplomatic, aid and development budgets. Finally, Australia should reinforce a Biden’s administrations’ predilection for alliances by early demonstrations of support for the alliance.

Red book

What happens under Trump

In a second Trump term, the contradictions of US policy on China will become more pronounced. Trump’s antipathy towards coalition building at home and abroad, his consistent affinity towards authoritarian governments and silence on their human rights records, and his long-held belief that free trade and multilateralism are loser’s bets will not moderate. The Trump administration will remain focused on seeking an aggressive and multi-faceted set of policies, even if it continues to see internal divisions between those seeking economic engagement on more advantageous terms, those bent on further disentangling the US and Chinese economies, and those looking to thwart Beijing’s actions across the board. These internal divisions would mirror broader Republican debates over how to square industrial policy with free-market principles, disdain for international institutions with concern for ceding key fora, organisations, and venues to China, and how to balance trade and security.

More specifically, a second Trump term would likely see an uptick in symbolically aggressive actions, a push for further bifurcation of the internet and increased regulation of the tech industry, further limits on people-to-people exchanges (such as the withdrawal of the US Peace Corps from China)49 and making permanent the restrictions on certain Chinese students and scholars studying in the United States. The number of prosecutions of Chinese nationals accused of espionage by the Justice Department will likely increase, as will the number of Chinese companies and officials sanctioned for Beijing’s actions in Xinjiang and Hong Kong. There will also continue to be a big push for reshoring manufacturing in the United States, even as Southeast Asia — and not the United States — continues to reap the reward of economic decoupling, and calls for larger defence budgets while cutting funding for diplomacy, foreign aid, and economic development projects.

Looming over all of this would be the prospect of a temperamental Donald Trump. The Trump administration has presided over the largest shift in US policy towards China in four decades, but Trump himself seems the greatest variable in this equation, regularly praising Xi Jinping, asking the Chinese leader for help with his re-election, viewing Huawei and ZTE not as potential threats to information systems but as issues to make personal concessions to the Chinese, and endorsing China’s crackdowns in Hong Kong and Xinjiang. As John Bolton, Trump’s former National Security Advisor recently wrote, “The Trump presidency is not grounded in philosophy, grand strategy or policy. It is grounded in Trump. That is something to think about for those, especially China realists, who believe they know what he will do in a second term.”50 Trump has shown himself hawkish on China only in terms of trade and in deflecting blame for his handling of the coronavirus pandemic. Ultimately, Trump feels no compunction undermining his administration’s stated policies, as he has done repeatedly.

What Australia should do

Australia’s stock will rise because of the policy choices it has made, in relation to other Asian allies, such as Japan and South Korea, and due to reasons that matter more to Trump, such as a positive trade balance, than to anyone else.

On the diplomatic front, a second Trump term might result in closer US-Australian ties, but that would likely prove the exception rather than the model for US alliances, as Trump puts more pressure on South Korea and Japan and increasingly turns away from, and possibly abandons, NATO altogether.

Another Trump term will likely result in more abrupt decisions in the area of decoupling with China, with direct and overt pressure on businesses to fall in line. With that said, there is also the distinct possibility that he will seek another trade deal with Beijing, since the one signed in January 2020 failed to curb China’s subsidies to its state-owned enterprises, did not halt rampant intellectual property theft of US businesses and technology, and did not result in increased Chinese purchases of American goods.

Australia will need to continue identifying areas of shared interest with the United States, and then use existing mechanisms and bilateral fora to pursue joint goals. Australia will also need to be prepared for a United States less committed to multilateralism and a White House that will not play a leading role in defending democracy around the world.

US foreign policy in Europe and the Middle east

Dr Gorana Grgic and Jared Mondschein

Overview: With the exception of China, the pressure for the US government to focus on domestic concerns — and not European or Middle Eastern issues — will likely be greater than any other post-Cold War presidency.

Biden contrasts with Trump: The Biden approach to foreign policy will prioritise restoring alliances, resuscitating multilateralism, promoting human rights, and confronting foreign dictators. President Trump’s foreign policy in Europe and the Middle East will remain unconventional and unpredictable.

What Australia should do

- Regardless of who wins the election: Burden-sharing and maintaining an active presence across all halls of power in Washington will continue to be paramount for US allies like Australia, particularly when the US focus will be increasingly dominated by domestic challenges.

- During a Biden administration, Australia should: Continue efforts in support of burden-sharing and the rules-based international system — including maintaining a robust defence strategy and expanding the revamped Trans-Pacific Partnership.

- During a second Trump term, Australia should: Maintain an assertive voice alongside the rest of the Washington establishment in underlining the strategic importance of the Indo-Pacific.

Long-term trends

Since the end of the Cold War, every US presidential election has featured candidates pledging to do less in foreign policy. Donald Trump in 2016 and Barack Obama in 2008 both criticised US involvement in Middle Eastern wars and pledged to withdraw US troops from the region. George W Bush in 2000 argued that the United States was “no longer fighting a great enemy” and emphasised that the United States “refused the crown of an empire." Bill Clinton told the public in 1992 that “foreign policy is not what I came here to do."

While each US president has subsequently faced criticism for overzealous foreign policy, the pressure on the president who is inaugurated in 2021 to focus on domestic concerns will arguably be greater than it was for any other post-Cold War presidency. These concerns include nationwide civil unrest, an economic recession, and a pandemic that has killed more than 200,000 Americans.

Barring unforeseen events, the one exception to this inward gaze will be China. Contrary to prior elections, both candidates are campaigning on who will do more on this specific foreign policy challenge. Issues in Europe and the Middle East, meanwhile, remain in the background to most Americans — largely seen as a distraction from more pressing issues.

In Europe, Americans will likely remain largely opposed to Russian aggression and in favour of maintaining alliances but with a strong emphasis on allied burden-sharing, which has bipartisan support in the Congress. And in the Middle East, the three drivers of recent US engagement in the region — combating terrorism, securing access to oil, and defending Israel — are simply not urgent priorities. Today, terrorism ranks last in a list of issues that Americans deem to be a “very big problem in the country today," the United States has largely secured energy independence, and Israel is enjoying unprecedented support from Arab nations and, therefore, fewer threats to its existence.

US foreign policy in Europe and the Middle East will continue to be dominated by the challenges presented by China at a level not dissimilar from the Soviet challenge in the Cold War.

Yet, the unfortunate reality is that the most successful strategy for confronting Beijing will require collective action in tandem with allies and partners. A US foreign policy solely focused on China alone will likely lead to less success because unilateral efforts weaken the US ability to confront Beijing.

The United States will maintain an Indo-Pacific Strategy (though perhaps branded differently) and China will remain the central challenge of that strategy. The United States will also continue to seek support of such efforts with allies and partners in Europe and the Middle East but, again, the challenge for US allies and partners is that practically all US foreign policy will be coloured by pressing domestic concerns and strategic competition with China, including seemingly unrelated developments.

US foreign policy in Europe and the Middle East will continue to be dominated by the challenges presented by China at a level not dissimilar from the Soviet challenge in the Cold War. This preoccupation with China will continue to feature in everything from international trade and defence agreements — as evidenced in the new US-Mexico-Canada Free Trade Agreement, which includes language targeting China — to domestic economic activities related to critical supply chains.

As much as domestic concerns and China will colour the focus of US foreign policy, the nature of how it is carried out will remain less inhibited. It should not be forgotten that it was the intractable nature of the United States’ challenges at home and abroad that, in many ways, fuelled Donald Trump’s candidacy. Many Americans concluded that the conventional approach had not achieved desired results so it was worth considering a new approach.

From slapping blanket tariffs on US allies, questioning the utility of NATO and moving the US embassy in Israel to assassinating an Iranian general, this unconventional approach to foreign policy has largely not been perceived by the US public to have resulted in the sort of catastrophe that many experts predicted. This has helped widen US foreign policy’s “Overton window,” or the spectrum of ideas considered palatable by the public.

In either electoral outcome, the American public will expect fewer losses of American lives and less money spent overseas in Europe and the Middle East. They will simultaneously tolerate more unconventionality in the execution of foreign policy than prior presidents employed, or even considered employing.

Blue book

What changes under Biden

The Biden approach to foreign policy will prioritise restoring alliances, the promotion of human rights, and confronting — instead of revering — foreign dictators. Multilateralism rather than unilateralism will be the default stance of a Biden administration, with a concerted push to resuscitate international organisations and deals that have been defanged and rolled back under President Trump — ranging from the World Trade Organization (WTO) and World Health Organization (WHO) to the Paris Climate Accord and Iran Nuclear Deal (Iran Deal).

These efforts will be acutely articulated in the Biden administration’s Summit for Democracy, a meeting of democratic nations to occur in the first year of Biden’s term of office. This gathering would, in Biden’s words, “renew the spirit and shared purpose of the nations of the free world.”

But after the summit, after the increase in rhetorical support for old allies and partners, and after the quick reversals of the Trump administration’s executive orders, the many foreign policy challenges facing the United States will not miraculously disappear. If anything, the problems will likely become more glaring because there will be less media distractions than was customary in the Trump administration.

Europe

Biden has surrounded himself with a team deeply committed to patching up relations with Europe51 given they are, at this point, at their post-Cold War nadir. More attention and assurances given to NATO and US-European Union relations can be expected.

Biden has also professed he will be much tougher on Russia — particularly on issues like election interference in the United States and hybrid warfare against US allies — since he views Putin’s regime as an adversary.52 At the same time, the administration will be pressed to find the right balance in sanctioning Russia for electoral interference and sabotage as it needs to avoid pushing it further into alignment with China.53

Overall, a Biden presidency offers prospects of much greater coordination with European counterparts on China — both on trade and security fronts. Yet Europeans remain far from unified in their stance on China.54 While various initiatives that will foster greater coordination and collaboration on China policy are coming from both executive and legislative levels in the transatlantic space, it is hard to envisage a united front that would encompass most of the European continent in the near term.

In this context, cooperation on trade matters will be one of the policy areas where there will be an early opportunity to develop a more unified front towards China, along with the added benefit of mending relationships damaged by Trump’s tariffs on European allies. A more ambitious undertaking, such as reviving the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership Agreement (TTIP) negotiations, seems to be more far-fetched at the moment as Biden campaigned on a “made in America” platform.55 Moreover, given treaty negotiations are approved by Congress, much will also depend on its ideological makeup. It is equally to be expected the United Kingdom will be actively lobbying for a trade deal with the new administration in the post-Brexit era, although this has not been set as a priority by Biden.

Given candidate Biden’s climate and energy policy platform, Australia might find itself pitted against the transatlantic agenda on green recovery. This is an area where Biden’s cooperation will pick up from where President Obama left, committing even further to work in the context of EU-US Energy Council or the more recently founded Alliance for Multilateralism.56

The Middle East

The combination of a strategic clarity resulting from fewer urgent issues being present in the region, the more limited domestic political value of the region to the Biden administration, and the more pressing concerns elsewhere will mean the region will garner considerably less attention from the Biden administration.

A Biden administration may seek to resurrect the Iran Deal, prioritise human rights in bilateral efforts with nations like Saudi Arabia, and rhetorically push back against Israeli annexation in the West Bank, but these efforts will not be top priorities — particularly in a first term.

A Biden administration may seek to resurrect the Iran Deal, prioritise human rights in bilateral efforts with nations like Saudi Arabia, and rhetorically push back against Israeli annexation in the West Bank, but these efforts will not be top priorities — particularly in a first term.

There will be some notable consistencies with the Trump administration on some key issues, including maintaining both strong support of Israel and a deeply felt scepticism of committing further US troops to the Middle East. And, having previously called himself a Zionist, Biden has also pledged to keep the US embassy in Jerusalem.

What Australia should do

While the rhetoric of the Biden administration will be a vast departure from the Trump administration, many of the key values — particularly urging allies and partners to do more burden-sharing and support efforts to maintain a rules-based international system — will go unchanged from the Trump administration.

As a result, Australia should continue its efforts in support of these values — whether that be through maintaining a robust defence strategy or expanding the revamped Trans-Pacific Partnership. This could also include segmented and issue-specific responses which Australia should take part in or further step up its involvement, as is the case with the Inter-Parliamentary Alliance on China.57

Australian efforts on these fronts would be welcomed by the Biden administration despite the fact that a more progressive US administration may decrease support for US military budget expenditures and US participation in foreign trade agreements.

Red book

What happens under Trump

President Trump has defied a lot of presidential history orthodoxy but he will likely follow at least one convention: In their second term and facing an oppositional Congress, post-Cold War presidents have tended to pursue a more active foreign policy and engage in legacy building. After all, it was in the second term of the Clinton, Bush, and Obama administrations that many of their most ambitious international efforts occurred.

With that said, few aspects of President Trump’s foreign policy in Europe and the Middle East will be conventional in a second term.

Europe