Executive summary

This report finds that China has dramatically increased its participation and leadership in the two largest global Standards Development Organisations (SDOs) — the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) — over the past few decades to become a leader in international standards. Specifically, China is now the most active participant across the two major global SDOs and has increased its number of leadership positions between five and 17 times in the Technical Committees that make up these SDOs, surpassing major Western powers. By contrast, some Western nations, including the United States, have let their engagement and shares of leadership plateau or even decline. This report examines leadership and participation patterns in the two largest SDOs to offer a nuanced understanding of their internal dynamics and external impacts at a crucial point in their history. The analysis in this report draws on a novel dataset constructed from more than two decades of annual reports, webpages and institutional data.

However, in utilising several metrics that act as proxies for national ‘innovation’ output, this report finds that China’s rise predominantly reflects its broader economic growth and innovation output, while OECD and especially European nations are overrepresented in these SDOs relative to their own innovation outputs. This report suggests that, while any risk of ‘capture’ or ‘distortion’ of these SDOs is yet to become apparent, such risks may emerge in the future. This finding is supported by a range of qualitative research reports across the past few years.

China has dramatically increased its participation and leadership in the two largest Standards Development Organisations over the past few decades to become a leader in international standards.

Even though the SDO system is still functioning adequately, reform is long overdue and becoming urgent. Typically, SDOs must constantly balance three sets of ambitions in international standards development: technical optimisation of the standards (e.g. safety and quality control); commercial motivations from the private sector; and government or national interests. However, alongside managing these ambitions and how they interact, the SDO-coordinated model of international standards is facing two interrelated problems in emerging technology policy that are currently adding external pressure.

The first is exogenous. A storm of geopolitical and emerging technology trends buffeting these institutions and their participants brings with it greater attention from policymakers. As technology plays an ever-more foundational role in providing for global needs like electricity and information, technology competition between the United States and China is ramping up. The private sector has risen to dominate ‘dual-use’ technology and innovation — formerly the domain of government agencies — and national security concerns are expanding into new policy areas, from infrastructure to trade. Together, these trends are reframing areas like international standards as arenas for competition over emerging technologies with commercial and military applications, like artificial intelligence, 6G telecommunications and quantum computing.

The second problem is an information challenge. There is limited understanding in policy and national security circles of the role international standards play in the global economy and the performance, efficacy and resilience of SDOs to hold true to their mandated roles. Such a lack of comprehensive knowledge or data on the performance of SDOs risks consigning any reform to the SDOs themselves to becoming a guessing game of untried ideas measured against unknown targets.

Combined, these two problems pose an existential risk to the current SDO-coordinated mode of international standards development that relies on compromise, consensus and global buy-in. A world without coherent standards risks global supply chains grinding to a halt with immense consequences, from inconsistencies in manufacturing to the sub-par production of pharmaceutical goods or unsafe food preparation damaging businesses and putting lives at risk. To prevent such catastrophe, there is an urgent need to tackle the challenge facing the SDO-coordinated system. This risk is particularly pertinent for the two largest SDOs with global reach, the ISO and IEC. These SDOs are the focus of this report, although another major SDO in emerging technologies, the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), is briefly examined.1 The insights explored in this report may prove indicative for other SDOs.

This report begins by setting out exactly what SDOs are, how they operate and their relationships with national standards bodies. It then examines the challenges they face — from ‘influence efforts’ to ongoing, structural shortcomings — before concluding with a set of policy recommendations to address these.

SDOs and the standards development process must be strengthened to maximise contributions from all nations and stakeholders and build robust, transparent and accountable procedures. This must be executed in a manner that avoids compromising SDOs to the point of stasis, capture or disrepair. Achieving this requires specific action, both by SDOs and governments, but would ideally also be undertaken or embraced at bilateral, minilateral or multilateral levels to drive consistent reform.

For governments like those in Australia and the United States, alongside their national standards bodies, this includes:

- Building coordination networks for national standards bodies to engage with policymakers in other relevant fields, including the national security community, to encourage cross-engagement while ensuring standards experts maintain their independence.

- Equipping national standards bodies to deliver increased training and participation incentives for the private sector to engage with SDOs (rather than a top-down, state or government-led approach).2

- Ensuring that participation by businesses and individuals in international standards development activities qualify for research and development tax credits, something currently not made clear by the US or Australian governments.

- Reviewing incentives to drive participation from those outside the private sector, such as civil society or academia.

- Providing technical experts with clearer instructions on what can be discussed at SDOs in relation to critical or dual-use technologies (those with both military and commercial applications). This would maximise their involvement while still recognising and accommodating national security concerns.

- Formalising long-term capacity-building between national standards bodies and their counterpart institutions across their region. This will foster best practice and bring regions into closer alignment with global standards. This could also involve integrating international standards into government procurement requirements.

- Such efforts, where possible, should leverage or be integrated with existing multilateral frameworks and organisations in a government’s region. This includes the Pacific Area Standards Congress (PASC), an organisation made up of standards-setting bodies from 25 Pacific Rim countries3 and the APEC Sub Committee on Standards and Conformance.4

- Alternatively, several current independent programs by countries could be expanded. In Australia, this could include formalising the initial two-year ‘International Standards Integration for Critical and Emerging Technologies in South-East Asia’ project, run by Standards Australia and sponsored by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT).5 In the United States, expanding the focus in the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s (NIST’s) ‘A Plan for Global Engagement on AI Standards,’ to cover critical and emerging technology areas beyond AI would be a logical and important next step.6

- Expanding secondments, fellowships and exchange programs for experts and staff between different national standards bodies, especially in their immediate region, to boost best practices in standards development.

- For example, expanding the ASEAN-Australia Digital Trade Standards (DTS) Initiative, implemented in part by Standards Australia, to consider coordination on standards beyond digital trade.7 Expanding this initiative’s Fellowship Program which focuses on emerging digital trade professionals to cover standards experts working on broader critical technology areas would be invaluable. If expanded, the Fellowship could potentially be run through the ‘International Standards Integration for Critical and Emerging Technologies in South-East Asia’ program, to ensure the ASEAN-Australia DTS Initiative remains focused on digital trade and the Fellowship is coherent with the existing engagement work of Standards Australia and the Australian Government.

For SDOs, this means:

- Improving public reporting and data on standards development — including votes, proposals submitted and contribution levels where possible — to increase transparency and promote organisational legitimacy.

- This would also enable improved qualitative and quantitative research into SDOs and improve understanding of how states and their representatives are influencing SDOs. Developing a clearer picture of the current system is critical to inform and refine any potential reform to international standards development.

- Continuing to invest in maximising participation and accessibility for technical experts in meetings and contributions.

- This could include ensuring meetings and engagements are run in a hybrid fashion (i.e. allow for virtual participation), where possible, or adopting technology enabled live translation options to allow more experts to engage in discussions that may not speak English, French or Russian (the official languages of the ISO and the IEC).8

Introduction

International standards play an integral role in the international economy and the emerging technologies that drive it. They underpin many of the technologies, products and services designed, produced and consumed globally — ensuring interoperability, improved safety and the consistent production of complex goods across the world.9 The rise of global trade depended heavily on the development of international standards — from the humble shipping container to software and telecommunications.10 As they are typically tied to technological innovation, standards are important to ensuring safe, sustainable and responsible approaches to new and emergent technologies.11 These advanced and emerging technologies underpin the “flows of information and energy”12 — together, the backbone of all modern economic activity.

For global ambitions like mitigating climate change, standards help ensure consistency between countries, technologies and companies. This enables the accurate measuring, reporting and accountability necessary to achieving global decarbonisation goals. In the realm of geopolitics, standards have been highlighted as a core component of the new force shaping international politics: innovation power.13

Increasingly, concerns have been raised over the distortion or capture of international standards by countries to advance their own national economic, geopolitical and technological ambitions. This began with the debate around 5G standards in the 2010s14 and has now arisen in the context of other emerging technologies like artificial intelligence (AI),15 quantum16 and electric and automated vehicles.17 In particular, standards have been considered as a component of geopolitical and technological competition between the United States and China.18 This has drawn additional scrutiny to the bodies that oversee international standards development, Standards Development Organisations (SDOs), and marks a departure from the historically hands-off approach of governments where standards development was predominantly left to each country’s private sector.

China concerns

Multiple accounts19 have flagged concerns that, as in other international forums and organisations, the Chinese state — through various public and private actors — has compromised these SDOs to advance its own authoritarian values. The Chinese state has used various tactics, including offering tax credits or subsidies to companies for the number of experts they send to SDOs, or for the number of proposals submitted by representatives.20 Much has also been made of the fact that the Standards Administration of China, the national body representing China at the two major international SDOs, is a public organisation — part of the State Administration of Market Regulation, which works below the State Council of China.21

In 2021, China released its latest national standards strategy — tied to the earlier ‘Standards 2035’ project released in 2018.22 The 2021 strategy sought to harness China’s approach to the sprawling realm of international standards in a manner that could uplift its industrial capacity and bring 85% of its domestic standards in line with international standards (although whether this means exporting domestic standards to SDOs or domestically implementing international standards remains unclear).23 The strategy also included reference to increasing industry (rather than government-led) involvement in standards development, albeit with the caveat emphasised by observers that at the same time, state-industry integration has grown ever closer in China).24 Primarily, these concerns are that the Chinese state is not just more involved and active in promoting proposals and standards at these SDOs, but that it is distorting these organisations to project its power and preferred values internationally.

Western strategies

Western governments have also been more forward in their preference for strategic government input into how their representatives or delegates engage with SDOs — including offering incentives for participation in standards development. Australia’s Department of Industry, Science and Resources (DISR) openly notes: “The Australian Government wants international standards for these technologies to reflect Australia’s values, innovations and expertise.”25 Standards also featured in the Australian Government’s 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper as part of the discussion of ‘soft power.’26 The 2023 US Government National Standards Strategy For Critical and Emerging Technology outlines that:27

“Strengthening the U.S. approach to standards development will lead to standards that are technologically sound, earn people’s trust, reflect our values, and help U.S. industry compete on a level playing field.”

In their ‘Implementation Plan’ released in July 2024 for the above strategy, the White House emphasised, amongst many other actions, providing “incentives” to promote SDO engagement by the government and other actors.28 However, the US strategy also notes that the “lifeblood of SDOs is good-faith engagement on the technical merits” and that their focus is on “increasing U.S. private and public sector engagement with SDOs”.29 The European Union (EU) has taken the promotion of preferred values by government a step further. The EU Commission’s 2022 Standardisation Strategy considers how standards fit into and support EU policy and legislation and adopts a more state-led approach, including creating an EU excellence hub to guide standardisation across member countries — rather than leaving it to non-governmental entities.30 A current example of this tension is the complexity involved in adopting SDO-developed standards on AI, such as ISO/IEC 42001:2023 — Artificial Intelligence — Management System, in the EU just as it simultaneously implements its own AI Act.31

All three — the EU, the United States and Australia — emphasise in their strategies the importance of standards reflecting their values and national interests while continuing to promote open innovation and the free flow of information.32 The increased state-led framing from Western nations is a marked shift from the historically hands-off, private sector-led approach to international standards.

Minilateral and multilateral groupings are also promoting values in international standards. In 2023, the Quad grouping — Australia, India, the United States and Japan — released the Quad Principles on Critical and Emerging Technology Standards, which emphasised that critical and emerging technologies should be influenced by “our shared democratic values” and human rights considerations.33 However, they also flagged support for the “industry-led, consensus-based multi-stakeholder approaches” taken in the development of international standards. Groups like the G7 also highlighted the centrality of international standards when building regulatory and non-regulatory frameworks for trustworthy AI.34 The G7 noted this should continue to be developed through “existing initiatives”, including specifically SDOs.35 Similarly, the US-EU Trade and Technology Council (US-EU TTC) has emphasised “mutually compatible” technical and international standards as a core tenet of their collaboration, including in areas of “strategic interest” like AI, quantum technology, 6G telecommunications and clean energy technologies.36

The increased state-led framing from Western nations is a marked shift from the historically hands-off, private sector-led approach to international standards.

It is worth noting that just because standards are being mentioned consistently in government policies, strategies and statements, does not necessarily translate into increases in on-the-ground engagement. For example, while the EU-US TTC’s Strategic Standardisation Information mechanism has been cited as an example of successful cross-Atlantic cooperation on standards, in reality, it has been labelled by some as simply an agreement to exchange emails “when it is considered useful.”37 While discerning the extent to which government’s posturing is reflected in action is complicated, standards development is still a predominantly private sector-led process in many Western countries, making both domestic (private-public) and international alignment on standards likely to be an ongoing challenge.

The need for a clear assessment

The increased attention given to SDOs as an arena for the contestation of values and technical dominance, and on China’s activity in these institutions, raises the question of what is actually taking place in these organisations. This issue is compounded by a lack of public and policymaker understanding and research into how standards are developed, or how the organisations that create them — SDOs — function.38 Numerous experts have emphasised the need for greater nuance in understanding how standards are developed and the operation of these organisations by policymakers.39 This includes those at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace,40 Brookings Institution41 and the Centre for Security and Emerging Technology.42 Amongst others, they suggest that a core risk is how policymakers interpret assessments of influence. These experts argue that to suggest China is all of a sudden dominating or dictating international standards — and that in response the United States and other Western states should agitate for major, government-led upheaval of these organisations — ignores the experiences of participants, the structures of SDOs and risks compromising these organisations as a result.

Without a considered understanding of SDOs and how they operate, there is a risk of knee-jerk reactions by policymakers that could compromise the open development of standards to ensure the safety, quality and interoperability of new technologies. This report dives into the fundamentals of international standards development to address this issue, before drawing on a unique dataset to provide a quantitative contribution on leadership and participation dynamics in the major SDOs, and their relationship with national innovative outputs. It concludes with a set of policy recommendations for government and SDOs that stem from this analysis.

Getting the basics right: International standards, national standards bodies and SDOs

Before delving into the data, it is critical to define and establish exactly what the major SDOs look like and how they operate to produce international standards. International standards43 — also termed voluntary or consensus standards — set out the characteristics against which a product, process or service can be evaluated and certified.44 For example, this can range from the overall dimensions of a shipping container to the design of its corner fittings, mechanical seals or tests of its structural strength.45 Other examples range from universal car dashboard symbols and aviation systems to Wi-Fi and bank cards — both of which can be used in almost any country. These characteristics are determined by consensus, “based on the consolidated results of science, technology and experience, and aimed at the promotion of optimum community benefits.”46 International standards are ‘living’ documents that are constantly updated or reviewed.

Most international standards are developed by SDOs, which coordinate the process and draw on a complex constellation of government, intergovernmental, industry and volunteer contributions to inform the final standard that they publish.47 While there is a myriad of SDOs that vary in scale, membership and structure — including some that are technology or sector-specific — the two largest are particularly influential and therefore the focus of this report.48

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) are critical to the current international standards development process. Together, their members represent about 97% of the world’s population49 and as of 2010, their work made up about 85% of international product standards.50 The ISO and IEC are ’sister institutions’51 and cooperate closely, including publishing standards under a joint technical committee — JT1 — that are listed as ISO/IEC standards.

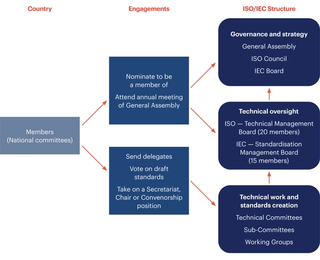

As shown in Figure 1, countries participate through national committees at the ISO and IEC, providing experts to contribute to Technical Committees, Sub-Committees and Working Groups — where the standards themselves are developed. Technical Committees and Sub-Committees are led by one nominated member country, the ‘secretariat’, while Working Groups are led by a ‘convenor’. In the cases of the United States and Australia, these national committees are managed by their national standards bodies — the American Standards National Institution and Standards Australia, respectively. Appendix A goes into detail on how the ISO and IEC operate and Appendix B sets out the national standards bodies of the United States and Australia as case studies for how countries interact with these SDOs.

Figure 1. General structures and roles in the ISO and IEC

Table 1. ISO and IEC summary (all dates are 2024 unless otherwise noted)

Sources: ISO in Figures; IEC National Committees; IEC Facts & Figures.

It is worth noting that SDOs are not just about emerging technologies. They cover all sorts of other areas (including logistics, process management, safety etc.), which can include refining standards for more mature technologies. The impact of each standard is not necessarily easy to measure (this is covered in detail in section 5. Muddying the waters). However, as an example, without standardisation in areas like credit cards (where ISO/IEC 7810 regulates their dimensions, thickness and corner radius, while other ISO/IEC standards cover electrical contacts and magnetic strips), international payments and withdrawals would be near-impossible for individuals when moving between countries, cities or even banks.52

A world without standards?

Without standards, the international supply chains of goods that support everything from healthcare and food supply to industrial machinery and home appliances risk grinding to a halt. One analogy for the friction (and potential risk) of a world without standards would be driving on the right or left side of the road. An Australian driving in the United States faces the mental friction of re-learning where to look when pulling into traffic, parking or navigating intersections. Yet, beyond the added inconvenience, this also increases the chances of accidentally pulling into oncoming traffic, putting the driver and passengers at grave risk. Additional layers of friction would emerge if other standards didn’t exist — from how seatbelts or child seats function to the symbols on the dashboard being inconsistent between countries — each adding confusion and potential risk.

Similarly, without clear standards for everything from electrical parts to food preparation, a world without standards would be a world without trust — either in other drivers, products from overseas or basic food goods. In the arena of emerging technologies, which often feature particularly complex global supply chains, standards are equally critical — foregoing them risks incoherent and inefficient production and greatly hampering innovation. Such a world would carry immense consequences.

Corporate entanglement — standards development should not just be defined in national terms

This report frames its analysis of SDO involvement in terms of ‘nations’, however, the full picture is not so simple. While the data available from the ISO and IEC defines participation and leadership in terms of nations, interviews with those involved in standards suggest that data on SDO participation and leadership by employer or sponsor would be just as valuable. With participation in SDOs led by the private sector (through a national standards body) and many technical experts being employees of the private sector, companies play a significant role in international standards development. In particular, with the international reach of many multinational companies, their influence on standards development could even surpass that of individual nations.

For example, consider an American company that employs technical experts in offices in Los Angeles, London, Frankfurt, Singapore and Sydney. This American company could provide the financial support necessary for their employees — who also happen to be leading experts in their technical field — to participate in standards development on behalf of six different countries. This is not to suggest that technical experts employed by large international companies are compromised or less qualified to serve as delegates to SDOs on behalf of their country or that they would preference the needs of their employer. However, given both the support needed for participating in standards development discussions (time off from work, funding for travel etc.) and the commercial benefits standards can offer companies, this factor cannot be ignored. This is likely to become increasingly important as governments pay more attention to standards development. Despite the challenges in collecting data on the employers or financial supporters of SDO delegates, it is an area that could benefit greatly from future research.

Setting the standard: China’s rise and Western malaise at the ISO and IEC

This section draws on a set of unique data, built from two decades of annual reports, archived webpages and institutional data to examine the leadership and participation trends at the ISO and the IEC.53 It charts China’s momentous rise to be a leader in these institutions and highlights that, despite the relative drop-off in the pre-eminence of Western nations, they still dominate the ISO and IEC across technical, management and governance levels. The subsequent section then contextualises each of these trends and highlights what this means for different countries, including rising powers like India.

Leadership

Across the IEC and ISO, there is one clear trend when it comes to leadership positions — the pronounced rise of China. As shown in Figure 2a, China’s leadership positions (secretariats and convenorships) at the ISO have grown more than 17 times from a mere 21 in 1998 to 373 in 2023. In particular, its leadership positions tripled between 2012 and 2023, catapulting China to hold the third-greatest share of leadership positions in 2023 — surpassing Japan, France and the United Kingdom between 2019 and 2022. As highlighted in Figure 2b, China’s rise over the past decade is momentous, increasing its share at more than five times the rate of the next-best, South Korea.

Figure 2a. Number of ISO secretariat and convenorship positions, 1998–2023

Figure 2b. ISO leadership positions change, 2013–2023

Figure 2c. IEC secretariat positions, 2012–2024, percentage of total

A similar trend is present at the IEC, with China almost tripling its leadership positions (secretariats) — from six in 2012 to 15 in 2024 (see Figure 2c). Despite this, it still sits sixth overall at the IEC and is a long way off Germany (38) or the United States (27).

Participation

The same trend continues when it comes to participation metrics — although China has arguably become even more influential here. Over the past two decades, China has gone from being a participating member (P-member) of 465 Technical and Sub-Committees at the ISO to 763 committees (see Figure 3a). In the process, it has exceeded the level of involvement of all the major Western powers. While the per-committee personnel figures are unknown (i.e. China could be sending one delegate to each committee, while Germany sends five), this rise marks a significant shift, and one not replicated by any other country across the past 20 years.

Figure 3a.

Number of P-memberships in ISO Technical and Sub-Committees, select countries, 2005–2024

Figure 3b.

Number of participation positions in IEC Technical and Sub-Committees, select countries, 2010–2024

At the IEC, China has not seen the same significant rise over the past 15 years. Instead, since 2010, it has maintained its position as a leading participant, sitting right alongside Germany and France. With the IEC only having 216 Technical and Sub-Committees in total, China’s position as a participant on 195 committees or 90% highlights how involved it is at this institution. It is worth noting that participation in and of itself does not necessarily equate to influence or valuable contributions to standards. For example, a smaller team of driven delegates can have far more impact than a larger team that is unorganised or unmotivated. As in other similar international processes that involve building consensus and offering compromise, after achieving an adequate number of delegates, it is more about the work of those that attend, than simply the fact they are there at all, that will be most influential in any final outcome.54

IEEE membership features a similar pattern

While the ISO and IEC are the largest SDOs, some other organisations are particularly prominent in specific or cutting-edge technologies. One such example is the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), an American professional association that has a large number of members (around 460,000 in 2023, made up of individuals and organisations) and publishes standards and peer-reviewed academic work.55 While the data available is far more limited, Figures 4a and 4b highlight membership figures for the top few countries — by standard and student membership, respectively. In a story similar to the ISO and IEC, China has been rising up the ranks. When it comes to standard memberships, China has overtaken Japan and Canada in the last 10 years and in the context of student memberships, it is not far from usurping the United States. Once again, the United States is in a decline, with membership dropping off in both total and percentage terms. However, just as significant is the volume of Indian memberships — triple the United States for student memberships and nearing 20% of all standard memberships. While European powers are not as prominent at the American-founded IEEE, similar trends to those at the ISO and IEC still prevail with China boosting its involvement (or membership numbers) while Western powers (here the United States and Canada) decline in both relative and absolute terms.

Figure 4a. Top five countries for number of standard IEEE memberships, 2013–2023

Figure 4b. Top four countries for number of student IEEE memberships, 2013–2023

Governance

This report focuses primarily on participation and leadership within the process of standards development — analysing those experts that represent nations in the development of standards at the major SDOs. However, the patterns of countries with influence are mirrored in the governance structures of both the ISO and IEC. The ISO’s Technical Management Board and the IEC’s Standardization Management Board are responsible for the overarching management of the standardisation process at each SDO.56 By contrast, the ISO’s Council and the IEC’s Board are each in charge of core governance and executive functions and report to their respective General Assembly.57

As set out in Table 2, the eight countries represented in all four of the governance bodies across the ISO and IEC are those that are also in the top echelon of countries for participation and leadership positions at the Technical Committee and Sub-Committee levels.

Table 2. Membership in governance bodies at the ISO and IEC, 2024

Sources: IEC; ISO.

Note: ISO TMB refers to the ISO’s Technical Management Body and IEC SMB refers to the IEC’s Standardization Management Board.

The most significant standout here is Australia, which sits on all four governance bodies across the ISO and IEC alongside heavyweight nations, outperforming its leadership and participation rates in the more technical standards development process. Beyond this particular highlight, it is the same nations that are most involved in the standards development process that also hold seats in the SDO governance bodies — showing the same countries holding sway across all levels of these organisations.

Western malaise or just a matter of perspective?

While not present across all of the above charts, there is an overall indication of a tapering off in Western engagement at the ISO and the IEC. This trend is most pronounced at the ISO, especially from around 2015. As shown in Figure 2a earlier, Germany, the United States and the United Kingdom have all declined in terms of their absolute number of ISO leadership positions, while the United States has also dropped off in terms of its participation figures (P-memberships in Figure 3a) — although other major Western nations have continued to grow their overall participation. In the case of the IEC, there is less indication of a decline in involvement — although there is some plateauing in major Western nations’ leadership positions — bar Germany and Austria.

However, focusing on the largest Western countries disguises the continuing dominance of the broader group of developed countries, especially the members of the OECD. As highlighted in Figure 5a, despite China increasing its leadership positions at the ISO more than 17-fold between 1998 and 2023, the OECD’s share has dropped by a mere 13%, still holding 84% of these positions in 2023. Even more significantly, the number of positions held by the rest of the world (excluding China and the OECD) has only grown from one per cent to 4.5% — a figure it has hovered at for the past decade.

Figure 5a. Share of ISO secretariats and convenorships, 1998–2023

Figure 5b. IEC leadership is also dominated by OECD nations, 2012–2024

The figures are even more pronounced at the IEC (Figure 5b), where the OECD has held more than 90% of secretariat positions across the past decade. Meanwhile, the share of the rest of the world (excluding China) has halved from two to one per cent. When examining participation levels at the ISO (in Technical Committees), it is clear that Western engagement is still prominent below the leadership level, as captured in Figure 6. The only major exception, as noted previously, is the United States, with a slight decline in participation to mirror their drop in leadership positions. Overall, this chart highlights the continued dominance of Western and European nations. However, there is one particular outlier, Iran, that has increased its participation by an astonishing 149 positions since 2017. While it is unclear what has driven this increased engagement, this is an anomaly that certainly warrants future research.

Figure 6. ISO participation positions change, 2017–2024

Despite China’s unparalleled growth and a drop in US leadership since 2015, the grip of Western nations on these organisations’ leadership posts is still strong.

Innovation and standardisation influence come hand-in-hand — but only for some

China’s rise is clearly significant, as is the relative slow-down in Western engagement and leadership. However, it’s important to contextualise these trends against a broader innovation and technology back-drop. This section draws on two sets of data that act as proxies for a nation’s innovative output — ‘patents in force’ and ‘scientific and engineering academic articles’ — to add context to the results set out above.

Patents in force

There is a clear positive relationship between the number of patents in force from a country and the number of leadership positions held at the ISO and IEC, as highlighted in Figures 7a and 7b. Whether these are directly related or simply benefit from other shared variables, such as resourcing or financing for participation and involvement, is an area that could benefit from future research.

The top six countries remain the same across both institutions — Germany, the United States, China, Japan, France and the United Kingdom. However, there are certain regional dynamics that these charts highlight. European countries — with Germany as a particular outlier — hold far more leadership positions than patents (i.e. sit below the overall trend line). By contrast, three Asia powerhouses — China, Japan and South Korea — alongside the United States, all have more patents in comparison to their share of leadership positions.

Figure 7a. Patents in force versus ISO leadership positions, 2022

Figure 7b. Patents in force versus IEC leadership positions, 2021

While these charts use patents in force rather than patent applications as their metric to try and capture only ‘proper’ innovations (i.e. only those which have been accepted as a patent), this only reflects one element or dimension of innovation — when an innovation is an invention that has public or commercial relevance.

Science and engineering journal output

To complement this, Figures 8a and 8b consider how ISO and IEC leadership compares with the output of national academic communities — measured here in terms of scientific and engineering journal articles. These show a very similar pattern to the number of patents in force — a positive relationship between the number of academic articles and the number of ISO and IEC leadership positions. However, as in the previous case, certain anomalies are evident. Across both charts, the gap between the United States and China, and all other countries, is far more pronounced, while a similar bloc of countries (this time a mix of European and Asian nations) outperform for leadership positions — including Germany, France, the United Kingdom, Japan, South Korea and Italy.

Figure 8a. ISO positions versus scientific and engineering academic articles, 2022

Figure 8b. IEC secreatariats versus scientific and engineering academic articles, 2021

Across both metrics for innovation output, China is a pronounced outlier, underrepresented in leadership positions at the ISO and IEC relative to the scale of its innovation. However, there are the caveats that patents in force and academic articles are only two potential metrics for the ‘innovative capacity’ of a state, and the well-documented use of subsidies and other state policies by China may skew these results.

How these findings fit into the broader literature on China’s SDO leadership rise

While data specifically on the potential ‘influence’ of China or other states would likely only be possible if voting patterns or submission rates were publicly available, several reports and pieces of research have attempted to address this question through qualitative means. Accounts of the Chinese state’s increased involvement and influence in SDOs vary greatly in scale and severity, resulting in very different assessments. These range from actual influence examples being cited as few and far between58 and “overblown”59 to assertions of systematic campaigns to compromise SDOs for national advantage.60

Despite this variation, there are two clear through-lines in these accounts. Firstly, there is consistent evidence presented across journalism,61 qualitative academic research62 and think tank reports (including examples from the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace,63 Brookings Institution64 and the Atlantic Council65) that Chinese representatives’ influence is increasing at SDOs. Secondly, however, is that this same evidence frequently cautions that China’s increasing influence is commensurate with its growth as a commercial power and that Western incumbents still dominate leadership positions66 — a thesis reinforced by this report. As the country with the greatest share of the world’s value-add in manufacturing and one of the largest economies,67 China’s increased involvement and leadership arguably reflects its growth into one of the world’s economic and technological leaders. Other analysis suggests that as they look to be involved in these SDOs, many Chinese companies such as Huawei have focused, initially, on hiring experienced Western practitioners in these bodies to represent them.68

As the country with the greatest share of the world’s value-add in manufacturing and one of the largest economies, China’s increased involvement and leadership arguably reflects its growth into one of the world’s economic and technological leaders.

China’s increased involvement and leadership arguably reflects its growth into one of the world’s economic and technological leaders. Other analysis suggests that as they look to be involved in these SDOs, many Chinese companies such as Huawei have focused, initially, on hiring experienced Western practitioners in these bodies to represent them. This thesis is also echoed by a recent study authorised by the US government on this exact issue. In 2021, a study was commissioned by the US National Institute of Standards and Technology and the Department of Commerce at the direction of the US Congress.69 It surveyed American industry on the “policies and influence” of the People’s Republic of China in the development of international standards for emerging technologies.70 The study concluded that, at least in 2022, the ISO and IEC were considered substantially robust in governance structures, safeguards and rules by the American private sector.71 They concluded that the increase in effective influence from participants backed by the Chinese state was minimal, despite their growth in active participation and submissions.72 This has been reflected in other reports and analyses.73 However, this is not to say that China’s influence may not, over time, become more prominent and effective — but that to date, this is yet to be the case.

It is worth noting that influence at one of the next-largest SDOs after the ISO and IEC, the ITU Tele-communication Standardization Sector (ITU-T), which features a more complex participation structure, is a slightly different story. In the study commissioned by the US National Institute for Standards and Technology, it flagged the ITU-T as an organisation where the Chinese state’s influence was more pronounced.74 In submissions, ITU-T participants bemoaned the lack of rigorous procedures and protections and noted that Sub-Committees were inundated with dozens of “low-quality proposals”.75 These have hampered the ability of Sub-Committees to function and lowered the credibility of the ITU-T, risking disengagement by private-sector members.76 This issue is also highlighted by a study that uses a new dataset of ITU ‘contributions’ to standards, which captured the monumental rise of Chinese companies in telecommunications standards — rising from four per cent of annual contributions in 2002 to 55% by 2021.77

However, taken together, these accounts suggest that the ITU-T is an outlier as far as effective influence is concerned — albeit one in need of reform. As submissions to the National Institute for Standards and Technology commissioned study highlighted, the ITU-T was not indicative of the broader SDO landscape and rather it was the ITU-T’s own differentiated structure that (unlike the ISO or IEC) allowed the growth in Chinese participation and influence to be not just present but effective.78

In conclusion, four outcomes are clear. As this data shows, China has achieved an unprecedented rise in its leadership and participation positions at both the ISO and IEC across the past two-and-a-half decades. At the same time, US leadership has waned, and Western influence plateaued. However, European nations continue to be overrepresented in ISO and IEC leadership positions, while the OECD still dominates in the respective governance bodies and holds more than 85% of either organisation’s leadership at the Technical and Sub-Committee levels. When examined against innovative output, despite China’s rise in the ISO and IEC, it is still arguably underrepresented, given its prominent role in the innovation behind many emerging technologies, such as battery technology. Finally, as set out above, a swathe of qualitative research suggests that, despite some fearmongering, the ISO and IEC currently continue to be considered robust, legitimate organisations that output credible and technically optimised standards devoid of overt political influence. However, with the concerning decline in the reputation of other SDOs, like the ITU-T, there are important areas for improvement to future-proof these institutions from political influence or capture.

What about India?

This report has focused on China’s rise to prominence. However, while the involvement of experts from some other emerging powers has increased (such as Iran in participation figures or South Korea in leadership figures), it is worth taking a moment to look at China’s closest regional comparison in terms of overall scale and potential growth trajectory: India. As highlighted in numerous graphs (especially in Figure 8a and 8b above), India sits far behind China and lags significantly for a country of its size in economic (fifth in the world for total GDP at almost US$4 trillion in 2024) and innovation terms (third in the world for the number of science and engineering journal articles released in 2022 with 207,390).79

Despite being outright third for the number of science and engineering academic articles in 2021 and 2022, India sits 15th for ISO leadership positions in 2024 with 24 and has exactly zero IEC leadership positions in 2024. When measured on a per-capita basis, India sits third-last globally (ahead of only Mexico and Egypt) for representation in ISO leadership positions. As captured in Figure 9, despite starting at a comparable position to China in the 1990s and early 2000s, India’s progress has been minimal. However, at the governance level of the SDOs themselves, India is more prevalent — holding positions across three of the four ISO/IEC governance bodies, the IEC’s Board and Standardization Management Board, and the ISO’s Technical Management Board. However, when it comes to active involvement in the process of standards development, India has not seen the same growth in leadership positions that China experienced, even as its economy and its innovative output (shown as academic articles in Figure 9) have grown significantly.

Figure 9. India’s minimal growth in ISO leadership positions, lagging behind its academic output, 2003–2022

India’s low level of leadership in the standards development process (despite its presence in organisational governance) is in spite of the fact that leadership at major international SDOs has been a stated goal of the Indian Government for half a decade. The 2018 Indian National Strategy for Standardisation noted that “continuous participation should be gradually translated into taking leadership positions...as well as winning secretarial responsibilities commensurate with India’s position as a leading global economy.”80 Additionally, the 2022 Standards National Action Plan from the Bureau of Indian Standards notes India should play a “leading role” in SDOs.81 Given China’s growth in leadership positions lagged behind its academic output initially (until around 2009), there is a strong possibility that India will likely begin to translate its academic output into leadership in standards forums over the coming decades.

For participation, India does fare better, sitting at 11th overall at the ISO and 15th at the IEC in 2024. In addition, at other SDOs, like the IEEE examined earlier that rely more on individual memberships, India is a prominent figure. It has triple the student IEEE memberships of the United States at 64,069 in 2023, and 86,716 full memberships — good enough for almost 19% of total memberships.

However, it is critical that India, as a significant producer of scientific and engineering academic work and a growing, major economy, becomes more involved in these major SDOs, particularly in a leadership capacity. As an increasing number of new countries become significant developers of emerging technologies in their own right, such as India, it is critical that their experts are involved in the development of technological standards through positions in organisations like the ISO and IEC. As one example, India is part of the aforementioned Quad grouping, which released the Quad Principles on Critical and Emerging Technology Standards as part of their work — allowing partners like India to align with other significant countries in their region on standards.82 Their increased involvement will not just improve the global applicability of standards in major growing economies and markets but reinforce the legitimacy of the major SDOs with states beyond the OECD.

Muddying the waters of standardisation: Different interests vie for dominance in SDOs

The above analysis focuses on leadership and participation. However, beyond simply showing up, there are other critical factors at play when a standard is being developed. Namely, three different interests compete to shape the final standard: optimising its technical performance, the commercial interests of private-sector industry and the national interest of governments.83 Sometimes, all three are in harmony. However, especially as governments pay more attention to forums like SDOs, these objectives can become increasingly interrelated, complex and potentially confrontational. To complement the above analysis, this section captures the different tensions that sit beneath the leadership and participation figures outlined above, which may go some way to explaining the complexity of the current challenge facing SDOs.

Technical optimisation

The goal of technical optimisation is based on the premise that standards are a key component of global trade and economic development — improving the interoperability, safety and quality assurances of products, processes and services.84 They help with breaking down trade barriers and building complex goods and supply chains between countries. By drawing from the “distilled wisdom” of a broad set of technical experts on the given topic, and building on previous iterations (for example, ISO standards work in a fashion similar to a stack of LEGO bricks), standards offer a best-practice solution that reflects the needs of those it has been developed to help.85 Under ISO/IEC Guide 2:2004, it is noted that the stated aims of standardisation include achieving: fitness for purpose, compatibility, interchangeability, variety control (i.e. minimising variety), safety, environmental and product protection.86 As the structures within which standards are developed, SDOs provide a “harmonised, stable, and globally recognised framework for the dissemination and use of new technologies.”87

As a result, much of the trust placed in products from global supply chains — by both consumers and producers — depends on adherence to international standards as arbiters of consistency in the quality and safety of products, their various components and broader production processes.88

Commercial benefits and trade impacts

Alongside offering a consistent benchmark for quality, safety and compatibility, the finalisation of a standard by a major SDO can also confer advantages to an industry or specific companies. It can “give first-movers a competitive advantage, and can generate significant revenue for companies with large patent portfolios” through the royalties they earn from others adopting their patented, now-standard technology.89 It also offers companies important interoperability benefits — whether along their own supply chains or with external suppliers.

Standards can also impose ‘switching costs’ on other companies in the industry that are not yet compliant with the new standard. This means that international standards can act as a de facto trade barrier for protectionist ambitions.90 They can allow states to limit market access — requiring that imports meet specific standards before being accepted — and therefore act as an additional barrier to trade, placing compliance costs upon exporters. However, unlike tariffs and other non-tariff barriers, international standards can also increase or expand trade. In some cases, they can cause both at the same time.

National interest

Traditionally, a government’s ‘national interest’ in standards has been on the grounds of the economic advantages they offer — an ambition interconnected with the commercial benefits noted above. However, efforts to empirically measure the overall benefit of standards to economic growth and trade have been somewhat varied, facing consistent challenges in measurement, varying net impacts and endogeneity (two-way causality) bias.91 Despite this, and marked inequalities between countries, the overall body of evidence shows that standards tend to benefit nations by boosting economic growth, innovation, productivity and trade. This section briefly touches on these different economic benefits in turn.

The overall body of evidence shows that standards tend to benefit nations by boosting economic growth, innovation, productivity and trade.

When it comes to the relationship between standards and economic growth, there is a relatively clear-cut, positive case. A 2021 ISO report that summarised 13 studies across a set of member countries (Australia, Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, New Zealand, South Africa and some Nordic countries) found that there was a consistent relationship between economic growth and an increase in a country’s stock (or total number) of standards adopted.92 Productivity benefits are similarly evident. A study by the Centre for International Economics conducted for Standards Australia suggested there is a positive relationship between the stock or total number of standards adopted and overall productivity — with standards acting as a means to diffuse knowledge.93

However, in the context of trade, the impact of standards becomes more complicated. As set out in a 2020 ISO-commissioned report,94 economic theory itself does not suggest that there is an inherent benefit that standards offer for trade. While standards may save firms from expensive information-gathering costs (they know exactly what is expected of their products), standards can also cause changes to products and production (adding further costs). Whether a standard’s impact is positive or negative depends on which effect is more influential. The report concludes that current evidence of overall effects is inconclusive — but it does suggest that any negative effects of standards are likely reduced over time as producers and nations adapt, and that standards can offer ongoing positive benefits for trade by signalling the quality of a given product.95

A similar OECD working paper by GMP Swann reviewed the empirical literature on international standards and trade.96 It concluded that, generally, standards had a positive impact on trade but conceded that the results were muddied by how the different economic impacts of these standards interact with one another. A study by Clougherty and Grajek on the most popular ISO standard (ISO 9000) suggested that, while the diffusion of the standard generally had a positive effect and increased trade, it was countries that were standards-rich (such as European nations) who benefitted most, while countries that lack in standards faced increased compliance costs to meet the new standard.97 As a result, in many cases, states will focus on building interoperability to help unlock the positive benefits of trade (for their own exporters and importers).

Standards also impact innovation in a unique manner. The aforementioned Centre for International Economics report noted that there is a sweet spot for standards implementation — putting standards in place too soon can hamper innovation, while doing so too late can ‘lock in’ inefficient or later-obsolete technologies.98 Standards also offer important platforms or baselines on which additional innovation can build and even spur innovation through the actual development of a standard.99

While these economic benefits are still being studied and debated, the nature of the ‘national interest’ that guides government perspectives on standards is also transforming. It is a long-recognised fact that technology is not developed in a vacuum — in its development, it is imbued with the values, ethics and principles of its creators.100 This has meant that part of the ‘national interest’ of governments in international standards has always involved the promotion of their national values.101 However, this element of ‘national interest’ in standards development, focused on promoting national values, is playing an increasingly prominent role in how governments perceive the development of international standards.

Geopolitics: A growing tension

As the world within which standards are developed is changing — from closer private-public partnerships and industrial policy102 to technological and strategic competition — tensions are starting to show in the current system. With states looking to compete for influence and dominance across different international organisations in emerging technology policy areas,103 frameworks like SDOs are coming under increasing pressure. Emblematic of this challenge is the role of individual representatives at Technical Committees and Sub-Committees.

Individual representatives that engage with these SDOs can be both acting as neutral, technical experts or represent their government or employer’s interests — although they typically coordinate through national standards bodies. While deliberating on the technical specificities of standards, member representatives are expected to act in their capacity as technical experts and based on technical merit, while also representing the interests of their member (at the ISO or IEC, their home country).104 For example, at the ISO, the chair of a Technical Committee is asked to “act in a purely international capacity, divesting him or herself of a national position”.105 This balance is likely to become increasingly challenging for representatives as other policy priorities (such as national security concerns) influence or determine what the ‘national interest’ may be when it comes to standards. In addition, the prominence of multinational corporations that may employ a large number of leading technical experts in a single field all across the globe offers an additional layer of influence. Put together, this complicates any effort to decipher who may be genuinely acting in the interests of their technical expertise.

Despite a focus on technical capability, standards offer potential commercial advantages and can allow for the embedding of particular national values. The core question is whether, or when, these commercial benefits and the national interest, ‘value-embedding’ dimension of standards development begin to distort or draw focus away from the other safety, interoperability and technical objectives of international standards. This is a question that governments and their representatives will need to carefully consider to avoid compromising the broader foundations of these SDOs.

SDOs are equipped with existing mechanisms and principles to balance commercial and government or national interests with technical optimisation

The growing external pressure driven by geopolitical events poses a risk to the continued functionality and legitimacy of the major SDOs. With a reputation centred on their technical expertise, like other regulatory bodies, SDOs have strong incentives to avoid any overt politicisation. Any evidence of political influence risks undermining their position of authority and their legitimacy as a result. To avoid politicisation and focus on technical optimisation, the major SDOs have ‘legitimacy ensuring’ mechanisms in place. These are underlined by two key principles — ensuring standards are consensus-driven and voluntary.

The development of standards involves a consensus-driven approach of deliberation, debate and compromise between all participants,106 with the goal of “the absence of sustained opposition...and to reconcile any conflicting agreements”.107 This is structurally embedded into specific stages in the development of a standard. For example, during voting on a draft standard by member countries at the ISO, it is only approved if two-thirds of the permanent members of the Technical Committee or Sub-Committee are ‘in favour’ and less than one-quarter of all votes are negative.108 In addition, any standards these organisations adopt are voluntary or non-binding.109 Not only is it very difficult for a single representative or member to have a standard passed, but even once approved, companies themselves can elect not to comply with those standards if they are considered sub-par (unless they are adopted by a government as enforceable regulation). In other words, SDOs can let the market decide.

A standard example: The shipping container

In devising standards for the now-ubiquitous shipping container during the 1950s and 1960s, participants of the ISO’s TC104 committee and the American Standards Association’s Materials Handling Sectional Committee 5 could not agree on a single standard.110 As a result, the ISO published a set of different options.111 Following this, private companies were able to assess which of these standards would suit their operations best — and over time, they settled on the 20-foot and 40-foot standard shipping containers that are still used today.112 These containers now carry around 60% of the world’s seafaring goods and are attributed as a critical factor behind the growth in international trade in the 20th century.113

Hard-won legitimacy

The ISO and IEC have also had to navigate crises in the past, but maintaining these principles has been vital. The creation of EU-wide standardisation architecture in the 1980s meant that the ISO and IEC’s most active participants, European nations, were focusing their resources on the intra-European body, rather than the IEC and ISO.114 The solution was to develop parallel processes, where the lead organisation — be they an EU standards body or a global SDO — would deliver its standard in a manner that aligned the requirements of the other so that both were kept in sync.115 After the ISO’s establishment in 1947, the IEC quickly struck an agreement for a joint technical committee — JTC1 — to allow the two organisations to coordinate as ‘sister institutions’ on areas of overlap.116] Throughout their respective histories, the ISO and IEC have consistently increased their institutional authority and legitimacy, built reinforcing collaboration networks and maintained their aforementioned governance principles in the face of crises or adversity.

The efficacy of these governance principles has also been empirically examined. This includes a particularly noteworthy study of the ISO,117 which concludes that these principles have been core to the ISO’s ongoing resilience and ability to dynamically adapt to crises across its more than seventy years of operating. Another study from the same academic volume examining the IEC’s resilience to crises comes to a similar conclusion — an unsurprising finding given the shared principles and status that both the IEC and the ISO hold.118

The risk of state overreach

As with many contested policy spaces for emerging technologies, a rapid, state-led response that lacks technical understanding and nuance risks inadvertently compromising what has, to date, proven to be a predominantly robust and effective global system of international standards development. Additionally, such a response could prove self-destructive.

Failing to lead or participate in the development of certain standards, either due to stringent national security requirements that dissuade private-sector actors from participating, or insufficient investment into a national body, is a de facto hand-over. It passes leadership of the conversation to those still actively involved. If the United States or other Western powers further reduce their engagement in major SDOs like the IEC and ISO (having already plateaued or declined), it would not stop standards from being developed. Instead, it would mean that other nations’ experts would step up to fill the leadership void and hold greater sway over the form those standards take.

To weather these challenges, SDOs must not only rebuff influence efforts but address other shortcomings to ensure they remain robust institutions that can deliver standards for decades to come.

Retreating from the major SDOs also carries economic risks. Several experts have highlighted that “a fractured system” of standards and their development would not only increase costs and friction in international trade but could reduce global compliance with safety standards.119 This would disadvantage companies from all countries and carry near-incalculable implications for the world economy and the operation of many supply chains far beyond the United States or China. As one expert noted, neither “China nor the West profits from a decoupling of standards and a fragmentation into distinct technological spheres.”120 A 2024 report from the US National Security Agency recognised this fact, noting that “[open], transparent, rules-based standards processes — processes that represent multiple stakeholders and do not give undue influence to a limited number of voices — are necessary” and alongside robust US participation, are in the economic and national security interests of the United States.121

As set out by this report, while the influence of the Chinese state has grown in SDOs, the existing principles on which SDOs operate — a consensus-driven, voluntary process with non-binding results — have, to date, withstood these influence efforts. However, with the increasing prominence of ‘values’ framing around international standards, there is a need to ensure SDOs are properly equipped to navigate these shifting priorities amongst their members and can still deliver on their technical objectives. This requires navigating complicated trends shaping international technology policy: technology ‘competition’ between the United States and China; the growth of ‘dual-use’ technology (with potential military and commercial applications) in the private sector; and the expansion of national security concerns within government as a result. To weather these challenges, SDOs must not only rebuff influence efforts but address other shortcomings to ensure they remain robust institutions that can deliver standards for decades to come.

SDOs have other issues that must be addressed

Beyond building a resilient system of SDOs that can stay true to their mandates, ensuring they address certain other concerns is critical to maintaining ‘buy-in’ from all members and standards continue to provide technical and economic benefits to those that participate.

Stakeholder participation and diversity

Boosting participation is arguably the critical ingredient to the long-term success of SDOs like the ISO and IEC.122 This includes not just increased participation by Western countries but ensuring the highest-quality input from as many participants as possible to help develop the most effective and technically optimised standards.

As economies across Asia, Africa and South America become more influential (and innovative), gaining their support will be necessary to ensure standards reflect their markets and the needs of their economies — and their support for the international system of SDOs as they integrate into the global economy and supply chains. Increased participation can ensure standards are applicable in more contexts — whether that be in production processes in different countries or different applications of the same product. A 2022 Brookings Institution study examining the performances of Australia, Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore and Vietnam in developing critical technology standards highlighted the significant intra-regional gaps in maturity between countries regarding standards.123 Closing these gaps (i.e. increasing the participation and engagement with standards in different countries across the region to a similar level) ensures countries adopt and integrate standards as their economies evolve, building greater synergies and alignment between neighbouring countries. Countries that are regional leaders in standards (such as Australia in the Asia-Pacific) should look to boost regional maturity when it comes to standards engagements — which has the potential to provide significant trade and economic connectivity benefits that boosts integration between different national economies.

As economies across Asia, Africa and South America become more influential (and innovative), gaining their support will be necessary to ensure standards reflect their markets and the needs of their economies.

There is a need to constantly improve the balance and diversity of stakeholders involved.124 As captured in Figure 10, Western countries still dominate the leadership positions of the ISO — a pattern echoed at the IEC. Additionally, a significant set of countries and regions are vastly underrepresented, such as Sub-Saharan Africa. Building representation not just geographically, but with different minority groups, will further boost the relevance and utility of standards to broader audiences.

Figure 10. Global distribution of secretariats of Technical Committees and Sub-Committees and convenorships of the ISO, 2023

The earlier data on OECD dominance again reflects this dearth of non-OECD or China leadership at the major SDOs. Countries other than China or those from the OECD only make up one per cent (IEC) and four per cent (ISO) of leadership positions — with these figures either static or in decline across both organisations over the past decade.

Table 3.

Participation (P-membership) and observer (O-membership) rates by different country groups at the IEC, 2024

Source: IEC.

As shown in Table 3, this gap is similar when it comes to engagement levels at the IEC, including the share of Technical and Sub-Committees in which different countries are active participants (hold P-membership) or are observers (O-membership). On average, the rest of the world, excluding China and the OECD, is an active participant in less than two per cent of the IEC’s Technical or Sub-Committees in 2024. Even as observers, the OECD average of 22% sits far above the 3.26% of the rest of the world. These stark differences across participation and leadership highlight what the ISO and IEC have consistently pointed out but struggled to address: there is a lot of work to be done in uplifting the participation of many countries.

Process transparency

Transparency is a critical dimension to the continued legitimacy of organisations like SDOs — and a core bulwark against criticism. Yet, transparency continues to be sorely lacking amongst SDOs. Issues around data and record-keeping in SDOs date back decades, with one 1986 NIST report citing a need for improved information availability to monitor international standards and SDOs.125

The data in this very report is emblematic of this issue. Data collection required internet archives to source historical iterations of webpages, manually extracting figures from annual reports and newspaper articles and sourcing data via reports from individual national standards bodies. Despite these efforts, notable inconsistencies and gaps in the available data make even comparing leadership and participation positions difficult across the ISO and IEC.

Transparency is a critical dimension to the continued legitimacy of organisations like SDOs — and a core bulwark against criticism.

Moreover, the current lack of transparency in SDOs obscures the “development history” of standards and the relative contributions of different members throughout their formation.126 There is no accessible aggregate data available that captures other critical metrics, including which technological areas different leadership or participant positions are related to (although this does exist at the country level). Similarly, no time-series data or material is made public about the voting patterns of countries at the technological area, standard or proposal levels. No material is available that captures the proposals tabled by different countries in the production of standards.

There is merit to maintaining a level of privacy to avoid accidental disclosure of confidential information and allowing participants at Technical Committees and Sub-Committees to engage free from undue scrutiny or pressure. However, future research into the major SDOs, which could help provide external, third-party examinations of their performance and efficacy, is made very difficult by the lack of available data. Without access to first-hand, comprehensive data, external research that could help drive improvements in the SDOs themselves is not possible.

Dual-use technologies and national security concerns

Finally, there is a need for an ongoing dialogue about how to navigate the increasing role of emerging technologies in national security. In the United States, current rules from the Bureau of Industry and Security prevent some technologies from being shared in standards development arenas like SDOs. This has meant that when entity-listed Chinese organisations are involved, US representatives have been forced to withdraw from the development of a specific standard they would otherwise contribute to.127 Some initial steps have been taken to improve this, with a 2022 interim final rule from the Bureau intended to exempt certain technology and software from Export Administration Regulations to specifically aid participation in standards development.128

Innovations in emerging technologies, including those that are dual-use (with commercial and military applications), now predominantly take place in the private sector, where previously these were driven by government-funded research. Yet, these innovations — including in areas like AI, quantum and electric or connected vehicles — are also becoming a core concern for national security in the United States, Australia and beyond. This increasing crossover between the private sector and government means that clear communication and boundaries must be established.

Maturing the dialogue and communication between government officials, the private sector and their national standards representatives will be vital. Additionally, there is a need for clear-cut expectations from government around what can and what cannot be discussed by representatives at SDO forums regarding these cutting-edge technologies. These can ensure that, where possible, standards continue to develop in ways that help build interoperable, safe and adoptable conditions for these technologies, while still addressing important national security concerns.

AI standards: Why it’s important to get national security interpretations right

The discussion around AI standards — arguably the area of greatest focus currently, given AI’s broader popularity — is indicative of the need to be precise and clear when it comes to national security interpretations and exceptions. In late 2023, two of the most prominent SDOs together announced a critical international AI standard — ISO/IEC 42001:2023, centred on the management of AI systems in organisations.129 As a certifiable framework for overseeing AI systems within companies that enables conformity and can build trust throughout international supply chains, it highlights exactly why an informed approach to standards setting by government is critical.130 ISO/IEC 42001:2023 has already been adopted by Standards Australia and is part of NIST’s ‘A Plan for Global Engagement on AI Standards’ in the United States.131 As highlighted by a recent report from the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, these international standards are key to national and economic security concerning strategic emerging technologies like AI.132