Executive summary

Technology is now the defining element of the Trump administration’s self-professed “strategic competition” with China:

- Washington is highly attuned to the long-term consequences and links between scientific progress, technological adaptation and national power in burgeoning US-China competition.

- Policymakers are attempting to balance efforts to maintain the open and global foundations of US and allied research and development systems, while deterring those that abuse its accessible and integrated nature.

- While President Donald Trump has been highly inconsistent on technological issues, Congress and the executive branch have slowly moved forward in executing the 2017 National Security Strategy and protecting what it termed the US National Security Innovation Base.

Congress and the Trump administration have embarked on a ponderous — and at times heavy-handed — effort to protect America’s technological advantage across multiple domains and through actions by several branches of government:

- Congress has expanded the powers of the Committee of Foreign Investment to review non-controlling investments in technology companies.

- New export controls are being rolled out which feature vastly more expansive definitions of “foundational” and “emerging” technologies, broadening their scope and potential reach.

- The Department of Justice has launched a major criminal justice campaign labelled the “China Initiative”, with the goal of prosecuting technology theft and enforcing existing regulations in every US state.

- Draft bills indicate the likely expansion of Congressional reform to halting the flow of US government funds flowing to overseas partners also involved in joint high-tech research and development (R&D) with China, affecting third parties like Australia.

Australia will be significantly affected by Washington’s unravelling of the US-China technological relationship, owing to its deep enmeshment with America’s scientific infrastructure. To navigate these changes in the national interest, Canberra must consider the following:

- Australia will face growing pressure to limit its science and technology interaction with China in critical dual-use fields in order to maintain technological collaboration with the United States in some emerging technologies, and may even be required to adopt restrictive export control policies.

- Australian research by universities, defence industry, business and government agencies will be seriously impacted by the United States’ expanded export control reform. Canberra should continue to lobby US policymakers on solutions, such as providing exemptions under the National Technology and Industrial Base framework.

- As the global technological ecosystem becomes more nationalised, securitised and difficult to navigate for industry and governments alike, Australia should implement a national research and development strategy that builds its own technological ‘counterweight.’

Introduction

Technology is the defining element of the United States’ growing strategic competition with China which Donald Trump first announced in 2017. The slow disentangling of technological integration between the United States and China that this competition entails will have significant consequences for allies like Australia, who are closely coupled with the United States’ scientific and technological infrastructure. While many have focused on the manufacturing and supply chain aspects of this competition, the US Government has also set about expanding its definition of what constitutes the industries, individuals and knowledge of its national security innovation base. This enlarged understanding, and the beginnings of a whole-of-government approach through various reforms and initiatives, will transform the terms of globalisation, international supply chains and even the US-Australia alliance.1 The likely result will be a further step in the transformation of the alliance from a purely geopolitical arrangement to a geoeconomic one as well.2

Washington and, to a lesser extent, Canberra are attempting to tackle the same problem: how to maintain the open and global foundations of the research and development and innovation systems that have ensured technological competitiveness in the past, while at the same time deterring Chinese efforts that seek to abuse their accessible and integrated nature. The United States has responded to this problem by gradually implementing an updated regulatory framework for its technological industrial base. Washington now considers actors like universities, academics and technology entrepreneurs who contribute to the development of science and technology essential to its national security. New rules, regulations and policies have been crafted to guard against intellectual property (IP) theft and the exportation of critical technologies. Some Chinese critical technology companies, like Huawei, have been specifically targeted by being placed on restrictive oversight lists.3 New powers have been given to bodies charged with providing oversight of foreign direct investment in critical industries. Immigration controls have made it more difficult for foreign students studying STEM subjects.4 Finally, a concerted criminal justice campaign has begun to better enforce laws governing the disclosure of foreign ties in the science and technology industry. These elements make up the initial stages of what Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) Director Christopher Wray has labelled a “whole-of-society response” to protect the United States’ economic competitiveness and technological edge.5

The way Australia’s science and technology ecosystem currently operates will be increasingly under strain in a “world of technologically driven competition.”

While the eventual extent of these policies is not yet known, it is clear the way Australia’s science and technology ecosystem currently operates will be increasingly under strain in a “world of technologically driven competition.”6 America’s policies are aimed at its strategic rival. But they will nonetheless have long-term global implications for close allies like Australia. Allies will face growing pressure to limit their science and technological interaction with China in critical dual-use fields and may be required to adopt restrictive export control policies in order to continue technological collaboration with the United States in some emerging technologies. Australians on the forefront of strategic technology include companies, universities, scientists and entrepreneurs. In interacting with the United States they will be confronted with new rules, regulations and barriers erected around funding sources, international collaborations and further legal oversight. While competition-driven challenges to supply chains, intellectual property protection, foreign investment and export controls will be spread widely in the US economy; the impact will be more acute for countries that are relative “takers” of technology, such as Australia.

Australian universities are on the frontline of this shift. As the producer, partner and location of much of Australia’s scientific, technological and commercial intellectual property, research universities are the most exposed to systemic changes in the US-China economic and technological relationship. This is due to both the nature of the security and economic relationship between Washington and Canberra as well as Australia’s reliance on international students and global research collaborations to cross-subsidise domestic R&D activity, a weakness which the fallout of COVID-19 has exposed.7 The longer-term impact for Australia’s greater technology base will be new American rules redefining US export controls around technological “end use” from the ones currently based on specification.8

The Australian Government will need to incorporate the acceleration of these trends into its assessments and planning, consider the consequences for Australia’s technology base and what avenues it can pursue to ameliorate them. The government should continue to work on current frameworks that allow for exemptions for close technological partners like Australia, such as the National Technology and Industrial Base (NTIB). Finally, Australia’s current approach to funding R&D will no longer be sufficient in a technological world that is more nationalised, securitised and competitive. Canberra must work to build its own technological ‘counterweight’ as a bulwark against global fragmentation allowing it to engage with strategic competition on its own terms.

Quick reference guide

National Security Innovation Base (NSIB)

Agency: The White House

Defined in the 2017 National Security Strategy, the NSIB expands the understanding of the US defence industrial base from large defence companies to include a wider network of stakeholders, including academia, National Laboratories, and the private sector.

Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS)

Agency: US Department of the Treasury

CFIUS is an interagency committee that reviews select foreign investment transactions in the United States.

Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act (FIRRMA)

Agency: US Congress

FIRRMA expanded CFIUS’s powers to review non-controlling foreign investments in technologies, companies and real estate that may have national security implications.

Export Control Reform Act (ECRA)

Agency: US Congress

Passed as part of the 2019 National Defense Authorization Act, the ECRA expanded US export controls to cover “foundational” and “emerging technologies.”

The China Initiative

Agency: US Department of Justice

The China Initiative is the name for a Department of Justice program focused on increasing investigations and prosecutions of intellectual property theft and espionage.

Immigration measures

Agencies: US Immigration and Citizenship Service (USICS); US Department of State

USICS has introduced harsher consequences for foreign students overstaying their visas.

Greater discretionary power has been granted to adjudicators processing foreign student visas, allowing them to deny applications or petitions without first notifying the applicant if necessary evidence is missing.

The State Department has begun actively restricting the visa applications of Chinese graduate students studying “aviation, robotics and advanced manufacturing” in the United States.

The transformation of US-China relations

The change in the United States’ China policy under President Trump has deep roots. As suggested in the administration’s 2017 National Security Strategy (NSS), there is a broad — and largely bipartisan — perception that China’s growing economic, military and technological power has to a degree been built on years of intellectual property theft through cyber operations, exploitation of open scientific and technological collaboration with the West, and unfair trading practices with the United States and its allies.9 Numerous cyber operations targeting US companies, universities and government agencies, attributed to Chinese national security agencies and state-sponsored actors have been well documented, with the 2014 indictment of five Chinese military officers for cyber espionage. This was the first time criminal charges were filed against known state actors and is a notable example.10 An agreement between President Xi Jinping to President Barack Obama to halt economic cyber espionage in 2015 lasted only a short time, with cyber-attacks attributed to actors based in China growing in 2016 (Australia forged a similar agreement with China in 2017).11 Further, in contrast to Australia’s sparse history of prosecutions for IP theft and defence export control infringements, the US Justice Department has documented a long history of economic espionage and targeted attempts to skirt defence export controls by individuals and companies linked to the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and the Chinese government and has brought multiple cases to court.12

This history — along with targeted high-tech industrial policies such as ‘Made in China 2025’, the growing authoritarian nature of the Chinese Communist Party, the militarisation of the South China Sea and the internment of the ethnic Uyghur minority in Xinjiang — has resulted in a broad bipartisan shift on China within the United States.13 Human rights, trade imbalances and China’s growing military power have united a diverse array of interests in the United States, including in Congress and the private sector, which has supported the administration’s shift to “great power competition” as laid out in the NSS and the 2018 National Defense Strategy (NDS).14

At their heart is the growing recognition within Washington of the long-term consequences and links between scientific progress, technological adaptation and national power in its competition with Beijing.15 In other words, both Republicans and Democrats increasingly place technology and its potential application at the centre of US-China competition.16 For instance, the Trump Administration 2017 NSS, and speeches and comments consistently made by senior administration figures since, frame the source of national power and economic prosperity as based upon maintaining America’s technological superiority.17 While the strategies state the need for further investment in R&D in emerging technologies as a main element of this competition, no major government initiatives have materialised since the previous administration’s 2014 Third Offset Strategy, which sought to leverage Department of Defense (DoD) investments to offset the deteriorating US military position in the Indo-Pacific.18 Bipartisan draft legislation, The Endless Frontiers Act, has been introduced which could invest up to $100 billion in the National Science Foundation to “maintain US global leadership in innovation.”19 But until then, a more ponderous and at times heavy-handed effort advanced by Congress and the Trump Administration has advanced across multiple departments and domains aimed at protecting the United States’ technological advantage.

Continuous competition in innovation: The US policy response

Since 2017, Congress and the Trump Administration have proceeded with a number of reforms first hinted at in the NSS, including expanding the idea of what needs to be fostered and protected concerning innovation networks and technology, foreign investment review, export controls and immigration. This collection of policy changes and enforcement represents a halting, but increasingly wholesale, effort to shield the United States’ technology base from IP theft, industrial intelligence collection and other threats:

National Security Innovation Base: As defined by the NSS, the National Security Innovation Base (NSIB) comprises all the inputs and actors critical to maintaining the United States’ technological qualitative edge and global competitiveness. This definition laid the framework for the more all-encompassing approach the Trump Administration has pursued in protecting the United States’ technological edge. Notably, the NSIB expanded the understanding of the US defence industrial base from large defence companies and more traditional industrial inputs to the “network of knowledge, capabilities, and people — including academia, National Laboratories, and the private sector — that turns ideas into innovations, transforms discoveries into successful commercial products and companies, and protects and enhances the American way of life.”20 The NSIB effectively redefined universities — including those that may be conducting basic research — small start-ups and the individuals which make up those organisations as part of the national security enterprise.

The National Security Strategy argues that maintaining a technological lead — critical to both US national security and economic advantage — requires a whole-of-government effort which is beyond the scope of any “individual company, industry, university or government agency.”

The NSS argues that maintaining a technological lead — critical to both US national security and economic advantage — requires a whole-of-government effort which is beyond the scope of any “individual company, industry, university or government agency.” Recognising many technologies which are beginning to form the basis of next-generation military systems and capabilities increasingly originate in inherently globally connected and financed universities, colleges and start-ups the NSS argues that protecting the NSIB will need to be both international and domestic.21 This, in part, laid the foundation for the US Government’s expansion of export controls to entire fields of technology, Committee on Foreign Investment reform, renewed investigation and prosecution of IP theft and disclosure laws, as well as coordination with allies.

Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) reform: The first major reform the NSS proposed to protect the NSIB was CFIUS reform. The equivalent to Australia’s Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB), CFIUS is an interagency committee that reviews select foreign investment transactions in the United States. In early 2018, Congress passed the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act (FIRRMA), expanding the powers of the Committee and the President to review non-controlling foreign investments in technologies, companies and real estate that may have national security implications. Principally, CFIUS’s expanded jurisdiction and review powers focus on the technology sector, with filings now required from foreign investors in “critical technologies, critical infrastructure” and businesses that may have access to “sensitive personal data.”22 While investors from Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom are exempt from filing with CFIUS in non-controlling transactions, they are still required if investing for a controlling stake in sensitive companies or real estate.

Transactions will only be subject to CFIUS review if they meet the definition of a “covered investment.” To meet this requirement, the transaction must afford a foreign person:

- access to non-public technical information;

- membership or observer rights on, or the right to nominate an individual to a position on the board of directors or equivalent governing body; or

- any involvement, other than through voting of shares, in substantive decision making regarding sensitive personal data of US citizens, critical technologies, or critical infrastructure.23

Sensitive personal data has a broad scope, encompassing such things as health-related data and financial data, and a business qualifies for CFIUS review if it relates to US Government personnel or maintains data on more than one million individuals.24 The new FIRRMA rules also require mandatory CFIUS filings for transactions in which a foreign government would acquire a “substantial interest” — or a voting interest of 25 per cent or more — in a relevant business. FIRRMA also expanded CFIUS control over real estate transactions when the property is located within or in close proximity to military installations or other government property related to national security.

As of April 2019, the Trump Administration has blocked three deals as a result of CFIUS recommendations. The administration reversed the purchase of hotel management software company StayNTouch after the group was acquired by China-based Beijing Shiji Information Technology Co. in 2018.25 In other cases, CFIUS has approved certain deals only after national security issues were resolved. Officials reportedly recommended the Trump Administration block German company Infineon Technologies AG’s proposed acquisition of Cypress Semiconductor Corp. due to the companies large amount of revenue from Chinese sources.26 However, the decision was approved by CFIUS after the German chipmaker entered a national security agreement with the US government.27 The case is an example of both the expanding range of factors CFIUS is considering when reviewing foreign investment, as well as the pressure it can bring to bear on companies seeking transactions in the United States. In addition, a number of Chinese companies have withdrawn or sold their investments in the United States following CFIUS recommendations, even before an official decision is announced from the Trump Administration.28

The expansion of US export controls: The second set of major policy reforms since the NSS has been the passage of the Export Control Reform Act (ECRA) of 2018.29 This set of policy changes to US Government export controls will likely have the biggest direct impact on Australia. Passed as part of the 2019 National Defense Authorization Act, the ECRA modified the existing US Export Administration Regulations to cover “foundational” and “emerging technologies” as part of US export controls. These changes are significant in that they largely reframe and expand US export controls from managing specific products to entire technological fields, an idea first flagged in an influential 2018 Defense Innovation Unit report.30 These specially designated technological dual-use fields include robotics, 3D printing, quantum computing, advanced materials, surveillance technologies, synthetic biology and machine learning among others.31

While the US Commerce Department is still formulating most of the rules laying out how these new controls will work in practice, it could mean that research and collaboration with, and within, any US-based organisation in many of these emerging dual-use fields may now fall under US export controls. The level of control and regulation on specific technological fields may vary and can range from applying for a license for any instance of export or retransfer of controlled knowledge to requiring a complete separation of workforces if persons are from an “embargoed” country, which includes China. In effect, the way many defence companies have structured themselves and operated for decades — under the auspices of strict and various export control regulations — could potentially be extended to other areas of the economy. In anticipation of the roll-out of the new regulations, some US-based technology companies have begun to draw up plans that would separate their workforces based on nationality.32

The second category of foundational technologies — potentially a broad list as it is understood as “existing technology already integrated into commercial products’” — is still being formulated but could include basic research and impact filing for patents and transferring technology between universities and industry.33 For instance, foundational technology could range from semiconductors that form some of the basic components of electronic circuits to the tech behind CRISPR, a novel and powerful tool that can be used to edit genomes. Reports indicate that ongoing debates within the Commerce Department revolve around whether to define technologies by their specifications, as most export controls are currently structured, or their applications, a much broader understanding and classification.34

While the Bureau of Industry and Security within the US Commerce Department is still working on what exactly will be included in these new categories, the export controls will be extraterritorial in the same way as existing US export controls operate. This means technologies in these categories are subject to US law, whether it is used by a US-based company or by “any company anywhere that is re-exporting American goods or technology; incorporating technology previously exported from the United States; and by persons subject to the jurisdiction of the United States.”35 As an example, geospatial imagery software, one of the first technologies to be classified under the new rules, now requires companies who wish to export it to apply for a license with the Commerce Department.36

Reportedly, the Bureau of Industry and Security is still undertaking consultations with industry and is likely to release rules on other technologies in the coming months. In the meantime, the bureau is moving ahead in other areas. In April 2020, the bureau amended existing export control regulations, removing exemptions that existed around some dual-use technologies like semiconductor equipment but also expanded the list of actors that would require licenses to export to, such as civilian companies that can be linked to supporting military applications, in China, Russia and Venezuela.37 Critically, the changes also require US companies to “file declarations for all exports to China, Russia and Venezuela regardless of value,” giving the administration substantial data into what exactly is being exported to strategic competitors.38 The rules state supporting the objectives of the NSS as the reason for their rollout.

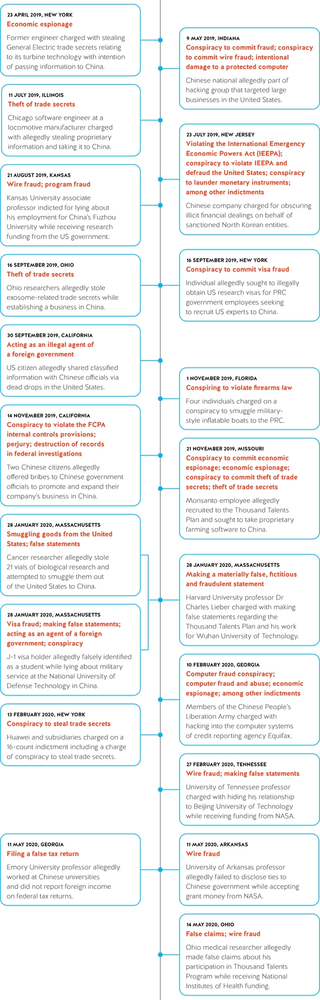

The Department of Justice’s China Initiative: Over the past three years the Department of Justice (DoJ) has stepped-up investigations and prosecutions of intellectual property theft and espionage under what it terms the ‘China Initiative,’ originally announced by then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions in 2018. Since the announcement of the Made in China 2025 industrial policy, Attorney General William Barr noted the department has brought trade-secret theft cases “in eight of the 10 technologies that China is aspiring to dominate.”39 As of February 2020, the FBI has “about a thousand” ongoing investigations into the attempted theft of United States intellectual property and technology; so far it has also made 19 arrests. DoJ officials expect that number to increase over the course of the financial year.40 Compared to the 15 individuals arrested for intellectual property-related cases over the previous six years, the rise in prosecutions reflects a concerted and focused criminal justice response to the rising threat of intellectual property theft presented by China.41 The goal, as stated by DoJ officials in early 2020, is to have each of the country’s 94 US federal district attorneys to bring cases as part of the overarching initiative.42

New investigations seek to more strongly enforce existing regulations and target actors not previously of interest to the Department of Justice, particularly in the higher education sector. For instance, existing policies requiring researchers to declare all potential conflicts of interest or foreign government affiliations are being more stringently enforced.43 The recent high profile arrest of the head of Harvard’s Department of Chemistry, Charles Lieber, for failing to disclose his links to Chinese research institutions while also working on US government-funded projects, is an example of the department’s more aggressive stance on academic disclosure. Another recent fraud case in West Virginia involves a professor claiming time off to care for a newborn, when in fact he used the time to take part in China’s Thousand Talents program.44 The department has also brought cases against Chinese-born faculty members at the University of Kansas, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, and Emory University, in each case for failing to disclose foreign ties.45 Cases involving universities, national laboratories and even hospitals, reflects the department’s focus on prosecuting IP theft in every sector of the NSIB.46

A timeline of the US Department of Justice’s China Initiative, April 2019 — May 202047

The Pentagon and the defence industrial base: The 2020 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) includes provisions designed to protect national security academic researchers from foreign interference, including measures aimed at streamlining gathering information on individuals involved in defence research and development activities.48 The FY2020 NDAA introduces a new interagency group tasked with identifying potential cyberattack threats and vulnerabilities in relation to research. The group will also offer policy guidance and recommendations on how best to secure research information from attacks, and how United States science and technology researchers may better be able to assist in federal missions.49

The Pentagon has also been concerned about weaknesses in the US defence industrial base itself. Following a 2018 White House-directed study into the status of the defence industrial base and manufacturing in the United States, the Department of Defense began to make strategic investments in critical national security components.50 For instance, in recent years the Defense Microelectronics Activity has awarded contracts to semiconductor manufacturers IBM Global Business Services and SkyWater Technology in an attempt to make up for production shortages in certain commercially unviable chips.51 Through March 2019, seven Presidential Shortfall Determinations were issued, identifying production shortfalls in lithium sea-water batteries, alane fuel cell technology, sonobuoys production, and critical chemicals production for missiles and munitions, materials and technologies, all critical for military operations.52 The determinations granted the DoD through the DPA Title III the authority to expand the domestic industrial base capabilities in these critical areas.

Department of Justice’s China Imitative: The Arrest of Harvard Professor Dr Charles Lieber

On 28 January 2020, the Department of Justice charged Dr Charles Lieber, Chair of the Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology at Harvard University, on two counts of making false statements in relation to his involvement in the People’s Republic of China’s Thousand Talents Program.53

A world-renowned chemist, Lieber has been working at Harvard since 1991 and is the Principal Investigator of the university’s Lieber Research Group.54 The group specialises in nanoscience technology and has received more than $15,000,000 in grant funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Department of Defense since 2008.55

The Department of Justice alleges that Lieber had performed work as a “strategic scientist” for Wuhan University of Technology (WUT) as early as 2011. According to the details of a three-year contract intercepted by the FBI, Lieber was allegedly paid US$50,000 per month and was required to work for WUT for no less than nine months a year. Lieber was also awarded more than $1.5 million to establish a research lab at WUT.56

In order to secure NIH funding, non-NIH groups are required to disclose all foreign collaboration and foreign sources of research support, as well as potential financial conflicts of interest provided by foreign universities or governments. The Department of Justice alleges that Lieber repeatedly lied to both Harvard officials and federal investigators when asked about his connections to the Thousand Talents scheme, claiming that he had never been a participant in the program.57 If found guilty, Lieber could face up to five years in federal prison and a quarter-million-dollar fine.58

Detrimental reform: Cracking down on “non-traditional intelligence collectors:” The 2017 NSS also flagged immigration as another area requiring action to protect the NSIB. Specifically, it saw foreign students studying science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) subjects from “designated” countries as potential “non-traditional intelligence collectors” and foreshadowed the need to implement visa reviews, restrictions and other policies to deter the transfer of IP to strategic competitors.59 The first step the administration took occurred in May 2018 when the US Immigration and Citizenship Service delivered a policy memorandum laying out new consequences for foreign students overstaying their visas, with single-day overstays resulting in three to ten-year bans.60 The following month the State Department began actively restricting visa applications of Chinese graduate students studying “aviation, robotics and advanced manufacturing” in the United States. Five-year visas for these programs were reduced to one year, with the requirement to reapply every year.61 In July 2018 improved discretionary power was given to adjudicators processing foreign student visas, allowing them to deny any application or petition without first notifying the applicant if “evidence in the record does not establish eligibility.” These expanded powers were eventually blocked by a court injunction but have since been added to public regulatory agenda plans for September 2020.62

Even as aspects of the administration’s immigration efforts have been held up in court, early indications are that they have impacted the number of foreign students seeking to study STEM subjects in the United States. A National Foundation for American Policy analysis found denial rates for H-1B visa petitions had risen from six per cent in FY2015 to 24 per cent in the third quarter of 2019.63 Further, the total number of foreign students studying in the United States also declined by 10 per cent during the same period.64 In response, China’s Ministry of Education issued a notice warning potential applicants that visas had been restricted for Chinese students wishing to study in the United States, as “the visa review period has been extended, the validity period has been shortened and the refusal rate has increased.”65 These policies, while attempting to deter economic and technological espionage, are likely to be highly detrimental to the US research base.66 For instance, while the policies appear to be based on the assumption that these students return to China after completing their studies in the United States, the vast majority of students apply for further visa pathways to remain and work in the United States, primarily in STEM fields.67

These efforts are likely not the last from the Trump Administration. Additional policies and Congressional bills have been proposed, including expanding the Department of Homeland Security’s vetting of university and school officials in charge of collating data on foreign students and persons on exchange, which would “prevent potential criminal activities or threats to national security” that may result through these programs.68 More specifically, identical bills introduced in the Senate and House in May 2019 by Senator Tom Cotton and Representative Mike Gallagher would ban the issuance of certain academic visas to researchers associated with the PLA.69 In May 2020 Republican Senators Tom Cotton and Marsha Blackburn went even further and introduced the SECURE CAMPUS Act, a bill that would ban Chinese nationals from receiving any visas to student science and technology subjects for graduate or post-graduate studies.70 Later in the same month, the administration officially announced a more targeted policy: students affiliated with PLA-universities studying in the United States would have their visas cancelled, impacting an estimated 3000 students.71

China-Taiwan semiconductor joint venture indicted for economic espionage

In November 2018 the Department of Justice brought indictments against the Chinese state-owned company Fujian Jinhua, the Taiwanese semiconductor manufacturer United Microelectronics Corporation (UMC), and three Taiwan nationals. The Department of Justice accuses those involved of engaging in a conspiracy to steal trade secrets from Micron Technology, Inc. — a semiconductor company based in Boise, Idaho.72

Micron is the only producer of dynamic random access memory technology in the United States — a leading-edge memory storage device used in a wide range of computer electronics — and the company controls between 20 to 25 per cent of the DRAM industry.73

Until recently, China did not possess any DRAM technology, but in 2016, Fujian Jinhua and UMC signed a technology cooperation agreement under which UMC would produce DRAM technology for the Chinese firm. The DoJ alleges that two former Micron employees stole DRAM related intellectual property from the company prior to being hired by UMC.74

One defendant is accused of having downloaded more than 900 Micron confidential and proprietary files while working at Micron and storing them on USB external hard drives or personal cloud storage, which allowed him to access the information while working at UMC.75

Following the indictment and subsequent US government sanctions, Fujian Jinhua ceased operations in March of 2020.

Australia and the evolving US-China struggle for technological advantage

Washington’s initial policy changes constitute a significant shift in the structural nature of the US-China technological relationship, which will have consequences beyond one-off and highly public cases like Huawei or ZTE. The ongoing crackdown on Chinese technology theft along with the raising of regulatory barriers will accelerate the establishment of increasingly distinct technological domains.

Australia is particularly exposed to this transformation. Australian research universities — often collaborating with both US and Chinese government agencies, state-owned enterprises and defence companies — could face significant disruption and limitation in who they partner with, how they structure their laboratories and the way they source funding. In terms of national security, Australia will face growing pressure from the United States to go further in protecting IP, particularly if Canberra continues to seek greater access to and collaboration with America’s defence industrial base. Lastly, the largely open and laissez-faire way Australia has structured and invested in its science, technology and innovation ecosystem over the past decades will no longer suffice in a more competitive world.

Draft legislation an indication of things to come

A number of bills have been introduced in Congress that would, if passed in their present form, give substantial new powers to the US Commerce Department to directly regulate the collaborations between US government funding agencies and third parties involved in research on critical technologies with Chinese partners.76 With China recently overtaking the United States as Australia’s “leading international collaborator” of co-authored articles in peer-reviewed scientific journals, such legislation will present significant consequences and dilemmas for Canberra and for Australia’s scientific ecosystem.77 While these bills are in draft form at present and may not pass, senators and members continue to introduce legislation — with more than 200 bills reportedly in Congress relating in some way to US-China economic decoupling — indicating the future direction the US legislature is likely to take in regulating America’s technological relationship with China.78

As opposed to export controls, these measures would be intended to stop US government funding going to institutions also conducting joint-research with certain Chinese government organisations. For instance, the China Technology Transfer Control Act of 2019, which was introduced in the House and Senate last year, would expand the powers of the State and Commerce Departments to restrict the flow of funds to foreign entities collaborating on projects that aligned with Beijing’s Made in China 2025 industry policy. In fact, the bill goes further to also encompass agricultural machinery, locomotives, advanced construction equipment and civil aircraft. The US House version of the bill was introduced with both Democratic and Republican signatories, but the US Senate version has only been backed by three Republican senators: Senators Josh Hawley, Rick Scott and Marco Rubio.

With China recently overtaking the United States as Australia’s “leading international collaborator” of co-authored articles in peer-reviewed scientific journals, such legislation will present significant consequences and dilemmas for Canberra and for Australia’s scientific ecosystem.

If passed, the bill would have significant implications for Australian entities — primarily universities — who have projects funded by US government-linked grants and are simultaneously collaborating with Chinese state-owned enterprises. For example, Monash University, which signed a $10 million research agreement with China’ state-owned aerospace company, the Commercial Air Corporation of China (COMAC), in October 2019 would likely come under scrutiny. The Monash-COMAC partnership reportedly focuses on joint R&D into the targeted fields of robotics, advanced manufacturing, artificial intelligence and big data, all areas of priority under Made in China 2025 and identified in the draft US legislation.79 Existing funding Monash receives from the US government would come into question. In 2018 Monash reported that its academics contributed to 1,533 co-publications with US-based researchers and had $7.7 million in funding from the US National Institutes of Health and the US Defense Department.80

As these bills have languished since being introduced to the House and Senate in mid-2019, it is unlikely they will progress in their current form. However, they are indications of the legislative direction Congress will take in protecting the NSIB.81 Republican senators have also introduced bills targeting improved screening of visa applications for researchers linked to PLA-linked research institutes and universities and have called specifically on Australia to introduce similar legislation.82 Other introduced bills increase the scope of the Department of Commerce’s Export Control List to include all 10 of the ‘core technologies’ identified in China’s Made in China 2025 plan.83 Republican senators have also proposed sanctions on foreign entities and individuals that commit cyber-espionage.84

Novel export controls, Australia and the National Technology and Industrial Base

For Australia, the issue of rising barriers around America’s advanced technology industry and research institutes could be solved with a functional National Technology and Industrial Base (NTIB).85 The NTIB is a legal framework that was expanded to include Australia and the United Kingdom in addition to Canada in 2017. It is an ambitious legislative agenda in the United States which aims to create a “defence free-trade area” between America and its closest allies.86 It is notable that in the rules issued so far, Canada — the longest-running member of the NTIB and America’s most integrated defence industry partner — was exempt from the export restrictions, but Australia and the United Kingdom were not. This irregular application of exemption rules to some members of the NTIB and not others further undermines the framework, creates growing opportunity costs for Australia and works against US interests to leverage allied defence industries to bolster its own military-technological edge.87

For Australia, the expanded export control reform now being implemented by the US Commerce Department could have a serious impact on universities, defence industry, business and government. The NTIB could be a vehicle for Australia to seek exemptions from these new regulations. America’s shift from ‘specification’ based export control standards (and currently the way Australia writes its own defence export controls) to a system based instead on the end-use of the technology, may begin to capture partnerships and research that currently does not touch the export control system. For example, specification export controls are based on a technical signifier or characteristic of a certain technology. A computer chip larger than a certain size can be exported, but not if it is smaller and made of more durable material.88 However, the looming regulations in the United States move towards targeting general end-use or application of the technology such as the recently released rules on geospatial software that aims to control any software “specifically designed” for training neural networks to analyse satellite images for specific purposes.89

For Australia, the expanded export control reform now being implemented by the US Commerce Department could have serious impact on universities, defence industry, business and government. The NTIB could be a vehicle for Australia to seek exemptions from these new regulations.

Further, many of the technologies targeted under these reforms — like artificial intelligence, big data and some biotechnologies — are still in the early stages of discovery. As basic or fundamental research — meaning they are not developed for specific technological applications — they would usually not fall under export controls. Maintaining the openness of the US basic research system and not regulating the majority of fundamental scientific exploration has been a long-standing policy of the US government.90 But many of these emerging technologies, like the inherently software-based development of machine-learning algorithms, can blur the easy distinction between what is fundamental scientific research and what can be immediately applied to real-world capabilities. The majority of computer-vision software research, for instance, may still be considered exploratory.

But the gap between the laboratory and applying it to real-world scenarios, potentially for security or military capabilities, is increasingly narrow in some fields. Basic research revolves around the publication of discoveries in open and globally accessible scientific and technical journals, China is known to systemically exploit open-source publications to reverse engineer products and circumvent the cost and risk of indigenous research. This adds to growing concern as to the effectiveness of the current export control and classification system.91

These broad changes in export policy will add to the regulatory burden for businesses, research institutes, start-ups and other organisations in Australia wishing to import emerging technologies or collaborate on research with entities in the United States. With only one rule officially issued by the Department of Commerce on satellite imagery analysis software so far, it is difficult to judge the full impact of these changes for Australia.92 However, it is likely that companies, defence contractors and researchers integrating emerging technology into Australian defence systems, experimenting with products or capabilities in the Australian environment and market, or looking to collaborate on research projects, will need to eventually apply for approval with the US Department of Commerce. Entities used to following an export regime that was relatively clear in what was and was not allowed will have to engage with a much wider and somewhat more ambiguous system. With no exemption carved out for Australia, like there has been for Canada with satellite imagery analysis software, broad categories of technology including data science, robotics, and biomedical science will be more difficult to access in Australia. The regulation may be particularly complex for the numerous start-ups, research labs and defence companies working on emerging technologies that have offices and personnel located in both Australia and the United States.

Building Australia’s technological ‘weight’

As the global technological ecosystem becomes increasingly nationalised, securitised and difficult to navigate, even with close economic and security allies like the United States, Australia should work to build its own technological ‘counterweight.’ This should be done through both establishing new non-US and non-Chinese R&D and scientific partnerships throughout the region and with other Five Eye partners, as well as rethinking how domestic technological innovation and research is financed. A more self-sufficient and dynamic R&D base will allow Australia to better weather the growing fragmentation of the technological world, make Australian partners more attractive for both US tech companies and research while simultaneously providing more ballast for Canberra’s lobbying of Washington for export control exemptions.

Generally, for the past several decades, successive Australian governments have taken advantage of the efficiencies globalisation has provided in terms of R&D. As R&D became more globalised over the past thirty years, and foreign student revenue grew as an export market for Australia, successive governments have tapered spending on domestic innovation. For instance, total Australian research spending as a share of GDP fell to 1.79 per cent in 2017-2018, down from a historical high of 2.25 per cent in 2008-2009.93 This is far below the OECD average of 2.37 per cent. Similar results can be found in Australian business investment in R&D.94 While Australia has pioneered several technologies that have had global impact, uninterrupted underinvestment in R&D spending — the basis of technological capability — has cemented the country as a relative “taker” of new technology rather than an exporter.95

A more self-sufficient and dynamic R&D base will allow Australia to better weather the growing fragmentation of the technological world, make Australian partners more attractive for both US tech companies and research while simultaneously providing more ballast for Canberra’s lobbying of Washington for export control exemptions.

This decrease in national R&D funding has occurred even as the global technology landscape has become more competitive and volatile for Australia. For instance, even the United States as the source of much of Australia’s defence and national security IP and capability has found its traditional technological dominance challenged as its global share of R&D spending fell from 40 per cent in 2000 to 27.9 in 2015.96 More importantly, the centre of global innovation and research spending has shifted to Australia’s region while Canberra’s policy has remained static. In 2015 R&D investment in East and Southeast Asia accounted for 40.3 per cent of the worldwide total, while North America’s total was 27.9 per cent and Europe’s 21.6 per cent.97

While there are lessons from several countries Australia could build upon, such as Israel or Germany, South Korea stands out as a nation that has applied industrial policy to its R&D capacity with notable success. Back in 1999, South Korea published a national scientific and R&D strategy with a vision to build the country into a technological powerhouse by the year 2025.98 Updated every five years, Vision 2025: Korea’s Long-term Plan for Science and Technology Development, has been a highly successful industrial policy that has seen long-term results. Seoul has grown its GDP expenditure on R&D from 2.21 per cent in 2000 to 4.52 per cent in 2018, one of the highest in the OECD.99 Korea also has the second-highest research intensity measurement in the OECD, behind only Israel, with many firms spending a significant amount of their budgets on R&D activity.100

While South Korea may not be the perfect comparison — Australia does not have the equivalent of Korea’s large industrial conglomerates, or chaebols — long-term planning has aided Korea in establishing some technological resilience. For example, in battling COVID investment in biotechnology, IT and a strong R&D base provided the tools for Seoul to contain the outbreak without extensive national lockdowns.101 Its prowess battling the virus has also allowed it to expand its global influence through exporting testing kits and pandemic expertise.102 In other areas, South Korea’s investment in R&D has allowed it to chart its own path in critical technologies like artificial intelligence and 5G.103 Similarly, building an R&D industrial policy that takes into account the changing nature of the global scientific ecosystem, the interlinkages between national security, civilian R&D and national resiliency over the long-term would better prepare Australia for a more contested technological world.

Conclusion

The United States has embarked on a whole-of-government policy towards its technological competition with China. While American leaders, most notably President Trump, have given conflicting signals on their stances towards high-profile examples of this competition — such as Huawei — this has often distracted from important, and sometimes damaging, policy changes legislated by Congress and now being implemented by the executive.104 A wholesale change in the day-to-day functioning of the world’s most important high-tech relationship will impact the role and direction of technology in globalisation. Australia has taken its own proactive steps, including being the first to warn its Five Eye partners of the dangers associated with foreign ownership of 5G networks, establishing its own Foreign Influence Transparency Scheme and updating its foreign investment review mechanisms.105

However, the regulatory divergence between the United States and China in terms of technology, scientific funding and supply chain security will go beyond actions Australia has taken so far to protect its own scientific and innovation base. Australia’s access, integration and collaboration with the United States’ leading technology hubs and minds will become increasingly predicated on its corresponding relationship with China. Many of the recent partnerships’ Australian universities, companies and even government science agencies have signed with China-based partners have been predicated as working on basic and fundamental science, or civilian-technologies that have seemingly little cross over with national security. Some of these agreements will come under growing scrutiny as the connections between scientific and technological progress, national economic power and national security continue to grow closer in the minds of policymakers. As it stands, large parts of Australia’s R&D base, a source of strategic and economic strength, may not endure the fragmentation of the world’s innovation ecosystem.