Executive summary

America no longer enjoys military primacy in the Indo-Pacific and its capacity to uphold a favourable balance of power is increasingly uncertain.

- The combined effect of ongoing wars in the Middle East, budget austerity, underinvestment in advanced military capabilities and the scale of America’s liberal order-building agenda has left the US armed forces ill-prepared for great power competition in the Indo-Pacific.

- America’s 2018 National Defense Strategy aims to address this crisis of strategic insolvency by tasking the Joint Force to prepare for one great power war, rather than multiple smaller conflicts, and urging the military to prioritise requirements for deterrence vis-à-vis China.

- Chinese counter-intervention systems have undermined America’s ability to project power into the Indo-Pacific, raising the risk that China could use limited force to achieve a fait accompli victory before America can respond; and challenging US security guarantees in the process.

- For America, denying this kind of aggression places a premium on advanced military assets, enhanced posture arrangements, new operational concepts and other costly changes.

- While the Pentagon is trying to focus on these challenges, an outdated superpower mindset in the foreign policy establishment is likely to limit Washington’s ability to scale back other global commitments or make the strategic trade-offs required to succeed in the Indo-Pacific.

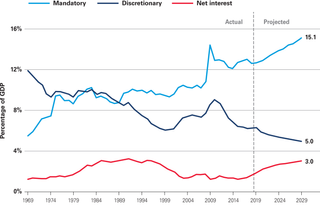

Over the next decade, the US defence budget is unlikely to meet the needs of the National Defense Strategy owing to a combination of political, fiscal and internal pressures.

- The US defence budget has been subjected to nearly a decade of delayed and unpredictable funding. Repeated failures by Congress to pass regular and sustained budgets has hindered the Pentagon’s ability to effectively allocate resources and plan over the long term.

- Growing partisanship and ideological polarisation — within and between both major parties in Congress — will make consensus on federal spending priorities hard to achieve. Lawmakers are likely to continue reaching political compromises over America’s national defence at the expense of its strategic objectives.

- America faces growing deficits and rising levels of public debt; and political action to rectify these challenges has so far been sluggish. If current trends persist, a shrinking portion of the federal budget will be available for defence, constraining budget top lines into the future.

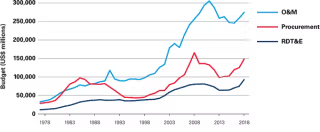

- Above-inflation growth in key accounts within the defence budget — such as operations and maintenance — will leave the Pentagon with fewer resources to grow the military and acquire new weapons systems. Every year it becomes more expensive to maintain the same sized military.

America has an atrophying force that is not sufficiently ready, equipped or postured for great power competition in the Indo-Pacific — a challenge it is working hard to address.

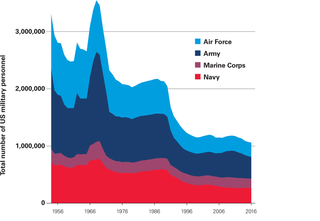

- Twenty years of near-continuous combat and budget instability has eroded the readiness of key elements in the US Air Force, Navy, Army and Marine Corps. Military accidents have risen, aging equipment is being used beyond its lifespan and training has been cut.

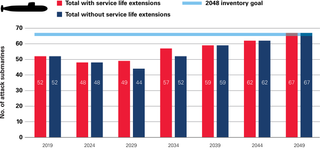

- Some readiness levels across the Joint Force are improving, but structural challenges remain. Military platforms built in the 1980s are becoming harder and more costly to maintain; while many systems designed for great power conflict were curtailed in the 2000s to make way for the force requirements of Middle Eastern wars — leading to stretched capacity and overuse.

- The military is beginning to field and experiment with next-generation capabilities. But the deferment or cancellation of new weapons programs over the last few decades has created a backlog of simultaneous modernisation priorities that will likely outstrip budget capacity.

- Many US and allied operating bases in the Indo-Pacific are exposed to possible Chinese missile attack and lack hardened infrastructure. Forward deployed munitions and supplies are not set to wartime requirements and, concerningly, America’s logistics capability has steeply declined.

- New operational concepts and novel capabilities are being tested in the Indo-Pacific with an eye towards denying and blunting Chinese aggression. Some services, like the Marine Corps, plan extensive reforms away from counterinsurgency and towards sea control and denial.

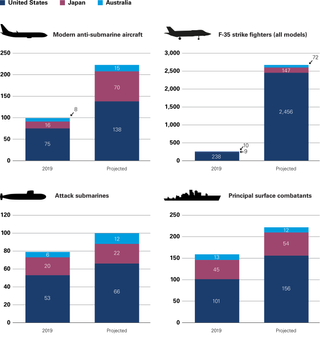

A strategy of collective defence is fast becoming necessary as a way of offsetting shortfalls in America’s regional military power and holding the line against rising Chinese strength. To advance this approach, Australia should:

- Pursue capability aggregation and collective deterrence with capable regional allies and partners, including the United States and Japan.

- Reform US-Australia alliance coordination mechanisms to focus on strengthening regional deterrence objectives.

- Rebalance Australian defence resources from the Middle East to the Indo-Pacific.

- Establish new, and expand existing, high-end military exercises with allies and partners to develop and demonstrate new operational concepts for Indo-Pacific contingencies.

- Acquire robust land-based strike and denial capabilities.

- Improve regional posture, infrastructure and networked logistics, including in northern Australia.

- Increase stockpiles and create sovereign capabilities in the storage and production of precision munitions, fuel and other materiel necessary for sustained high-end conflict.

- Establish an Indo-Pacific Security Workshop to drive US-allied joint operational concept development.

- Advance joint experimental research and development projects aimed at improving the cost-capability curve.

Introduction

America’s defence strategy in the Indo-Pacific is in the throes of an unprecedented crisis. It is, at its core, a crisis born of the misalignment between Washington’s strategic ends and its available means. Faced with an increasingly contested regional security landscape and with limited defence resources at its disposal, the United States military is no longer assured of its ability to single-handedly uphold a favourable balance of power in the Indo-Pacific. China, by contrast, is growing ever more capable of challenging the regional order by force as a result of its large-scale investment in advanced military systems. Although the past 18 months have seen renewed efforts by the US Department of Defense to prioritise the requirements for great power competition with China — a key objective of America’s 2018 National Defense Strategy (NDS) — Washington has so far been unable or unwilling to sufficiently focus its armed forces on this task or deliver a defence spending plan that fits the scope of its global strategy. The result is an increasingly worrying mismatch between US strategy and resources that jeopardises the future stability of the Indo-Pacific region.

The drivers of this crisis are multi-faceted and likely to persist. At the strategic level, Washington’s commitment to an expansive liberal-order building agenda — including nearly two decades of counterinsurgency wars in the Middle East — has dangerously overstretched its defence resources. This has left the US armed forces ill-prepared for the kind of high-intensity deterrence and warfighting tasks that would characterise a confrontation with China. While the Pentagon is trying to refocus on preparations for future great power wars, an outdated superpower mindset within Washington’s foreign policy establishment continues to limit America’s ability to scale back its other global commitments or make the hard strategic and military trade-offs required to prioritise the Indo-Pacific.

An increasingly worrying mismatch between America’s strategy and resources jeopardises the future stability of the Indo-Pacific region.

This problem is being compounded by developments in the regional military balance. Having studied the American way of war — premised on power projection and all-domain military dominance — China has deployed a formidable array of precision missiles and other counter-intervention systems to undercut America’s military primacy. By making it difficult for US forces to operate within range of these weapons, Beijing could quickly use limited force to achieve a fait accompli victory — particularly around Taiwan, the Japanese archipelago or maritime Southeast Asia — before America can respond, sowing doubt about Washington’s security guarantees in the process. This has obliged the Pentagon to focus on rebuilding the conventional military capabilities required to deny Chinese aggression in the first place, placing a premium on sophisticated air and maritime assets, survivable logistics and communications, new stocks of munitions and other costly changes.

At the domestic political level, meanwhile, Congress has struggled to deliver annual defence budgets commensurate with the ever-expanding demands of America’s global strategy. The impact of the Budget Control Act’s legislative caps on defence spending over the past decade, coupled with repeated funding delays and budgetary uncertainty, has hobbled America’s ability to effectively respond to a deteriorating strategic landscape in the Indo-Pacific. Growing polarisation between Republicans and Democrats over national spending priorities, coupled with looming fiscal challenges, is likely to impede the political consensus required to achieve sufficient real growth in defence expenditure to implement the National Defense Strategy. At the same time, above-inflation growth in key accounts within the defence budget will leave the Pentagon with fewer resources to grow the military and acquire new weapons systems.

All of this has resulted in an atrophying force that is not sufficiently ready, equipped or postured to fulfil a strategy of conventional deterrence by denial in the Indo-Pacific. Indeed, the combination of two decades of near-continuous combat operations, budget dysfunction, aging equipment, and the rising cost of advanced military hardware has severely impacted the quality and quantity of America’s high-end armed forces. This has produced an accumulation of readiness problems and deferred modernisation priorities that must now be simultaneously addressed, placing additional strain on a defence budget that has only recently started to recover from a long period of austerity. While America’s military services have started to implement much-needed changes to their capabilities, posture and operational concepts to bolster conventional deterrence vis-à-vis China, it is far from clear that the Pentagon will have the budgetary capacity or strategic focus to deliver these in a robust and timely way.

This is not to say that America is becoming a paper tiger. Washington still presides over the world’s largest and most sophisticated armed forces; and is likely to continue to supply the central elements of any military counterweight to China in the Indo-Pacific. But it does mean that the United States’ longstanding ability to uphold a favourable regional balance of power by itself faces mounting and ultimately insurmountable challenges.

Australia should be deeply concerned about the state of America’s armed forces and strategic predicament in the Indo-Pacific. In order to realise shared defence objectives in the face of these challenges, Canberra would be wise to increase security cooperation with Washington and other like-minded partners to advance a strategy of collective regional defence. Such a strategy would see capable middle powers — like Australia and Japan — aggregate defence capabilities to offset shortfalls in America’s regional military power and hold the line against Chinese adventurism. This kind of collective action is not without risks and must be conducted prudently, including by remaining ever vigilant about America’s capacity and willingness to underwrite a regional balancing coalition. But as Australia’s freedom of action and ability to evade military coercion ultimately depend on the preservation of a stable strategic order, contributing to collective deterrence in the Indo-Pacific is the best way for Canberra to assist in averting a deeper crisis.

Part 1: Strategic challenges and overstretch

America’s military primacy in the Indo-Pacific is over and its capacity to maintain a favourable balance of power is increasingly uncertain. This is the stark reality facing US defence strategy today. After nearly two decades of costly distraction in the Middle East, the United States is struggling to meet the demands of great power competition with China and faces the uncomfortable truth that its armed forces are ill-prepared to succeed.

The stakes could not be higher. Since the early 1950s, America’s position in the Indo-Pacific has rested on its ability to defeat aggression, protect a network of allies and preserve a strategic order in which no single nation dominates. But this foundation of stability is now under strain. China’s military is increasingly powerful, while America’s warfighting edge has dangerously eroded. Many now warn that the United States might fail to deter — or could even lose — a limited war with China, with devastating consequences for the region’s future strategic landscape.

Alert to these risks, the US Department of Defense is taking steps to retool the armed forces for high-end warfare and focus greater resources on the Indo-Pacific. Its core aim is to bolster the balance of power by developing new ways for the United States and its regional allies and partners to deter Chinese adventurism with conventional armed forces, even in the absence of America’s traditional all-domain military dominance. The stability of the broader regional order hinges on the success of this denial strategy.

Meeting this challenge, however, requires hard strategic choices which the United States may be unwilling or unable to make. In an era of constrained budgets and multiplying geopolitical flashpoints, prioritising great power competition with China means America’s armed forces must scale back other global responsibilities. A growing number of defence planners understand this trade-off. But political leaders and much of the foreign policy establishment remain wedded to a superpower mindset that regards America’s role in the world as defending an expansive liberal order. This mindset, if it persists, will continue to overstretch defence resources, increase future warfighting risks, and prevent the robust implementation of US military strategy in the Indo-Pacific.

American primacy and the crisis of strategic insolvency

For more than 70 years, the United States has worked to maintain its pre-eminent global position by upholding favourable balances of power in the world’s most strategically significant regions — Europe, the Indo-Pacific and the Middle East. This, at its core, has been a military enterprise.1 Although trade, diplomacy and soft power have all played key roles, America’s unrivalled capacity to project combat power abroad and outmatch its adversaries has been the ultimate guarantor of a strategic order based on the continuous pursuit of military primacy. American power has deterred and defeated military aggression by aspiring regional hegemons. It has enabled the United States to sustain a vast network of allies and partners that further enhances its strength and global reach. And, following the collapse of the Soviet Union and America’s “unipolar moment”, it has facilitated Washington’s pursuit of an ambitious liberal order-building agenda targeting rogue states, combating terrorists and policing a long list of other global dangers.2

America’s armed forces have underpinned the Indo-Pacific balance of power for much of this period. Ever since the Second World War, Washington’s “defensive perimeter” in the Western Pacific — stretching along what is now known as the First Island Chain, from Japan and the Ryukyu Islands archipelago down to Taiwan and the Philippines — served as a check on the rise of Soviet and Chinese power.3 Its five treaty alliances in the region — with Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, Thailand and Australia — along with its defence assurances over Taiwan have mostly provided for deterrence and mutual restraint between China and its neighbours. In terms of force posture, large-scale defence facilities in Hawaii, Guam and Diego Garcia, and forward operating bases in Japan, South Korea, Australia and Singapore, as well as access points in several Pacific Islands nations, have enabled Washington to sustain a robust military presence across this vast maritime region. Crucially, America’s ability to guarantee the security of regional allies and partners has served as the quid pro quo for uncontested US primacy and provided the geopolitical basis for its power projection into the region. Although there have been limits to what US power could achieve, especially during the Vietnam War and on the Korean Peninsula, America’s uncontested primacy in the Indo-Pacific has deterred major power aggression, maintained regional stability and safeguarded freedom of access to international waters and airspace.

America’s Joint Force — the combined strength of its five military services — no longer has the resources, force structure, technological edge or operational concepts to fully achieve its global commitments.

Today, none of this can be taken for granted. According to a growing number of leading voices in the US national security community, Washington is facing a crisis of “strategic insolvency” in which the ends of its global strategy now outstrip its means.4 This judgement is premised on a bleak assessment of the current state of the US armed forces. As the congressionally mandated National Defense Strategy Commission puts it: “America’s military superiority — the hard-power backbone of its global influence and national security — has eroded to a dangerous degree” making it possible that Washington “could lose the next state-versus-state war it fights”.5 Analysts at the RAND Corporation have reached similar conclusions, arguing that the military is “failing to keep pace with the modernizing forces of great power adversaries, poorly postured to meet key challenges in Europe and East Asia, and insufficiently trained and ready” for major war.6 In short, America’s Joint Force — the combined strength of its five military services — no longer has the resources, force structure, technological edge or operational concepts to fully achieve its global commitments. Its capacity to uphold favourable regional balances of power by deterring great power challengers is increasingly in doubt.

At least four inter-related factors have produced this dangerous mismatch between America’s capabilities and top strategic objectives. Most, alarmingly, are self-inflicted wounds caused by years of unstrategic behaviour by both sides of the political spectrum.

First, nearly two-decades of war in the Middle East has taken a serious toll on the Joint Force, wearing out large parts of the military and leaving it ill-prepared for great power competition. Military readiness — or, the armed forces’ preparedness for combat — has been a particularly grave problem. Owing to the high operational tempo of counterinsurgencies in Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria, in addition to the military’s other global commitments, overall readiness fell to dangerous levels as the services struggled to meet unsustainable demands for overseas deployments, maintenance and training.7 By 2017 this situation had become a crisis: Only a third of the Army’s brigade combat teams were prepared for deployment, less than half the Air Force was ready for a high-end fight against a peer adversary, the Navy was facing a self-described “readiness hole”, and 53 per cent of Naval and Marine Corp aircraft were deemed “unfit to fly”.8 Although these numbers have started to recover, their corrosive effects on the Joint Force will take time and resources to repair. As then-Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Joseph Dunford noted in March 2019, the military “cannot undo decades of degradation in just a few years”.9

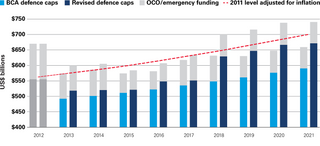

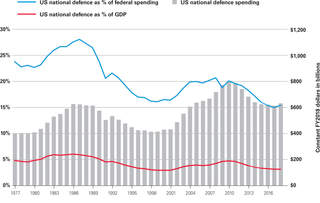

Second, while the United States was demanding ever more from its armed forces, it was simultaneously reducing its expenditure on defence and thereby compounding the strain on an already overstretched military. The root of this problem was political dysfunction within Congress.10 Following the Budget Control Act of 2011 — a congressional mechanism designed to reign in the federal deficit — real national defence spending fell from its FY2010 peak of US$798.6 billion to just US$613.3 billion in FY2017.11 This amounted to a US$550 billion loss in net buying power between 2012 and 2017.12 Making matters worse, as annual defence budgets became unpredictable in size and were not passed on time, the Pentagon was hindered in its ability to allocate resources efficiently and in a strategic way. The impact of all this exacerbated the military’s readiness crisis and was devastating for the overall size of the force. As a result, by 2016 the Army, Navy and Air Force were either at or approaching their lowest end-strength numbers since the Second World War.13

Third, the combined effect of a constrained fiscal environment and the unrelenting tempo of conflict in the Middle East has compelled the armed forces to underinvest in preparations for great power competition.14 This is a case of the urgent crowding out the important.15 Over the past two decades, critical military modernisation priorities — from the procurement of fifth generation fighters and investment in advanced technologies, to the recapitalisation of America’s nuclear triad — have been deferred or slowed by the overall squeeze on resources.16 The consequences of this failure to modernise have been dire. Not only has it contributed to the erosion of America’s technological superiority vis-à-vis peer competitors, but it has left the military with an increasingly outdated force that may be “irrelevant” for the kind of highly-contested scenarios that will characterise future wars.17 In General Dunford’s words: “Seventeen years of continuous combat and fiscal instability have affected our readiness and eroded our competitive advantage”.18 The same is true of the way that personnel training has also prioritised the near-term demands of counterinsurgency ahead of more strategically important mission sets. As Jon Kyl and Roger Zakheim, formerly with the House Armed Services Committee, have warned: The military’s sustained focus on the Middle East has created “a generation of war fighters that is ill-equipped and untrained for a conventional fight with ‘great powers’”.19

Finally, the global scope of America’s liberal order-building strategy has distracted the Pentagon from focusing on the most serious threats to US primacy: The return of China and Russia as militarily advanced great powers. This, in many ways, is the underlying driver of strategic insolvency today. Since the end of the Cold War, the expansion of American security commitments to a total of 69 countries, along with Washington’s overly ambitious democracy promotion agenda, has set the United States on an unsustainable strategic trajectory.20 Although this liberal order project appeared feasible in the 1990s, it became prohibitively expensive as the costs of military interventions from the Balkans to the Middle East stacked up, and as the diffusion of sophisticated defence technology saw more and more adversaries acquire potent counter-intervention capabilities.21

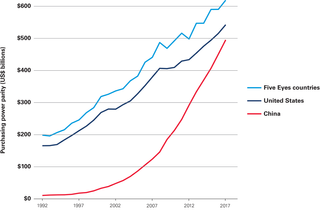

America’s capacity to enforce its vast liberal order has also correspondingly declined. Whereas the United States and its allies accounted for 80 per cent of world defence spending in 1995, today their share has fallen to just 52 per cent — leaving them less well-equipped to address an ever growing line-up of international challenges.22 As Harvard University academic Stephen Walt observes of US strategy during this period: “The available resources had shrunk, the number of opponents had grown, and still America’s global agenda kept expanding”.23 The consequences of this overstretch are now coming home to roost. Not only have the direct costs of liberal order-building been astronomical — by some estimates, the Department of Defense has spent over US$1.8 trillion on the global war on terror since 11 September 2001 for little strategic payoff — but the worldwide diffusion of American resources and attention has left the military underprepared for the return of great power competition.24 This is what the Pentagon is now working to address.

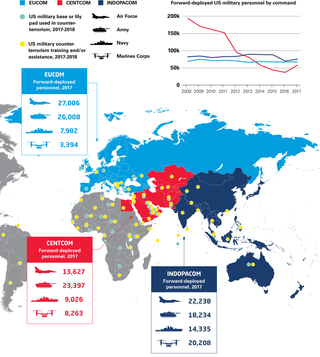

Figure 1: The scale of America’s global military presence and counterterrorism activities

Refocusing on China and great power competition

The Department of Defense’s 2018 National Defense Strategy sounded a clarion call for prioritising great power competition and rebuilding America’s military edge. It is, in many ways, a direct attempt to address the burgeoning crisis of strategic insolvency. Heavily influenced by then-Secretary of Defense James Mattis and his strategy team, its overriding aim is to jolt the Washington security establishment out of its strategically undisciplined approach to foreign policy and defence. To this end, the NDS is explicit about the most important threats facing America, declaring that: “Inter-state strategic competition, not terrorism, is now the primary concern in US national strategy” and should be the central organising principle for the Pentagon’s efforts to emerge from “a period of strategic atrophy”.25

Its authors are extremely clear about why this grand strategic course correction is needed. As Mattis stated during the launch of the strategy: “Our competitive edge has eroded in every domain of warfare — air, land, sea, space and cyberspace — and it is continuing to erode”, particularly vis-à-vis great powers like China and Russia.26 The NDS singles out the Joint Force’s “backlog of deferred readiness, procurement and modernization requirements” as the key factor behind this worrying trendline, attributing it to “inadequate and misaligned resources” and the effects of years of conflict in the Middle East.27 To rectify all this is a major political-military challenge. Acknowledging that “America’s military has no preordained right to victory on the battlefield”, the NDS warns that policymakers will have to make “difficult choices” if the United States is to successfully refocus its armed forces on long-term strategic competition with peer adversaries.28

While the NDS lists both China and Russia as great power threats, China is portrayed as the more formidable — and is by far the most significant challenge to US interests over the long term.29 Its rising power lies behind the strategy’s overall emphasis on strengthening high-end warfighting readiness, military lethality and advanced capabilities in preparation for future contingencies. In this regard, the NDS builds on the “Rebalance to Asia” and “Third Offset Strategy” which also sought to focus defence resources on strategic competition with China, albeit with less clarity and rather limited results.30 But it goes further than previous defence strategy documents in diagnosing the challenge China poses to America’s strategic position.

Amplifying the Trump administration’s 2017 National Security Strategy, the NDS contends that China is leveraging its military modernisation as part of an “all-of-nation” strategy to obtain “Indo-Pacific regional hegemony in the near-term and displacement of the United States to achieve global pre-eminence in the future”.31 This bleak assessment of Beijing’s intentions — coupled with the fact that China may have, or could soon develop, the military and economic capabilities to realise these aims — explains why the Pentagon’s strategy team elevated the deterrence of China to the top tier of America’s strategic priorities.32 China is the US military’s “pacing threat” for high-intensity combat, whereas Russia — with the exception of its nuclear arsenal — poses a somewhat less formidable challenge and is predominantly a veto player in its own region.33 It follows that ensuring a favourable balance of power in the Indo-Pacific to check possible Chinese aggression is of the upmost importance to US strategy. While the NDS does not rank geographic priorities, the Department of Defense’s Indo-Pacific Strategy Report of June 2019 formally identifies the Indo-Pacific as America’s “priority theatre”.34 This clarity of focus is an important step-change in Washington’s declaratory policy.

But it is what the NDS calls on the Joint Force to be able to do that marks a genuinely significant break with the Pentagon’s standard operating procedures and a tangible shift towards prioritising the military requirements of great power competition. This is apparent in the way its authors have recalibrated the US military’s “force planning construct” — the yardstick by which the Department of Defense determines the overall size, shape and composition of its armed forces.35

Breaking with 25 years of American defence strategy, the NDS tasks the military with preparing to comprehensively defeat one great power adversary, rather than two mid-level regional challengers in simultaneous conflicts.36 As its lead architect, former Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Strategy and Force Development Elbridge Colby, has explained: The NDS places a clear priority on ensuring the fully mobilised Joint Force is able to prevail over China or Russia in strategically significant, plausible high-end combat scenarios and elevates this goal ahead of the force structure requirements for defeating the likes of Iran, North Korea or the myriad global threats that the United States has become accustomed to fighting in twos and threes.37 By moving from a “two-war” to a “one-great power war” force planning construct, the Pentagon seeks to both lift the warfighting standard of America’s conventional forces and reduce the burden they face in dealing with multiple secondary priorities.

“Strategies that promiscuously enumerate threats, and call for equivalent vigilance between great powers that can change the world and rogue states and terrorists that cannot, will diffuse and squander Washington’s scarce attention and resources”.Elbridge Colby, former Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Strategy and Force Development, May 2019.[38]

This shift is motivated by strategic and budgetary necessity and will entail difficult trade-offs to fully implement. Crucially, it is based on the recognition that in an era of limited resources and intensifying great power threats, the United States needs to be far more disciplined about preparing its armed forces for major war. In terms of defence strategy, this means paring-back unnecessary global commitments and finding less resource intensive ways to fight terrorists or deter “opportunistic aggression” by regional challengers.39 Regarding force structure, this means prioritising the military’s capability (the quality and sophistication of its assets, and its ability to perform high-end tasks such as penetrating contested airspace) over its capacity (the overall size of the force and its bandwidth for undertaking multiple tasks at once). Modernisation, in other words, must be privileged ahead of growing the force.

Although this is not a purely zero-sum choice — Colby makes clear that the military needs a “high-low mix” of exquisite capabilities and cheap, attributable assets to succeed in a future great power conflict — it highlights the overall military-strategic trade-offs that America must make.40 Continuing to require the Joint Force to plan for two simultaneous wars — in terms of its major force elements, logistics, personnel numbers and support systems, etc. — risks leaving the force ill-prepared for the most demanding future warfighting tasks. In the words of another key member of the NDS team Jim Mitre: “Given the Department of Defense’s eroding military advantage relative to China and Russia, capability must be prioritized over capacity to enhance the lethality of the force and retain credible conventional deterrence”.41

Addressing the China challenge: The need for deterrence by denial

Arguably the most far-reaching change in the National Defense Strategy is its emphasis on conventional deterrence by denial. In the face of growing Chinese military strength in the Indo-Pacific, this is put forward as a better way to defend America’s allies and partners and uphold a favourable balance of power.42 Importantly, it marks a fundamentally different approach to deterrence and warfighting than the “all-domain dominance” model that the US military has grown used to in the post-Cold War era.43 In its simplest form it is a return to direct defence: Rather than seeking to deter enemy aggression by threatening to respond after the fact with overwhelming military punishment, deterrence by denial works by making it prohibitively difficult or costly for an enemy to secure its objectives by using force in the first place.44 Like the Pentagon’s slimmed-down force planning construct, however, this shift is also born of strategic necessity — and will be extremely difficult and require major trade-offs to implement.

This move from a strategy of punishment to denial is based on the sober recognition that the much-vaunted “American way of war” is no longer feasible against powerful adversaries like China and Russia.45 Pioneered with devastating effectiveness in the 1990-1991 Gulf War, the American way of war is founded on the United States’ ability to slowly and safely amass an “iron mountain” of military power adjacent to an adversary’s homeland and then, at a time of Washington’s choosing, launch an overwhelming assault to suppress enemy defences, establish all-domain dominance and rapidly achieve operational success.46 It is the embodiment of America’s global power projection prowess. By leveraging a number of competitive advantages — such as access to forward bases, precision strike, a large force structure, and advanced command, control, communications, computing, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (C4ISR) — the US Joint Force has successfully employed this warfighting approach against non-nuclear rogue states from Yugoslavia to Libya. Yet, as former Pentagon official and NDS staffer Christopher Dougherty explains, these competitive advantages will not hold up against a great power like China. Having meticulously studied the US military’s modus operandi, Beijing has “devised myriad strategic and operational counters” and capabilities designed specifically to target vulnerabilities inherent in the preferred American way of operating”.47 These have irrevocably undermined America’s military primacy in the Indo-Pacific.

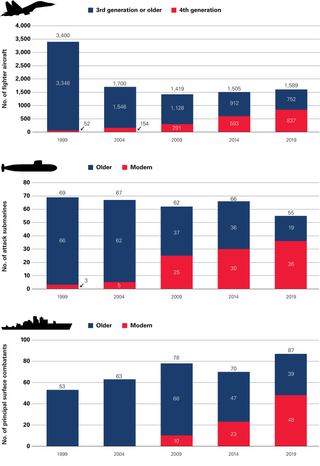

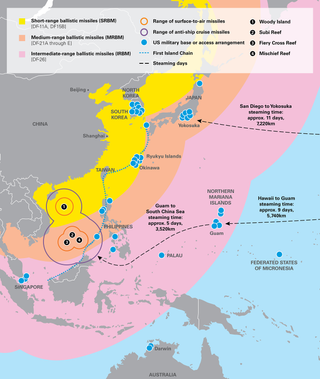

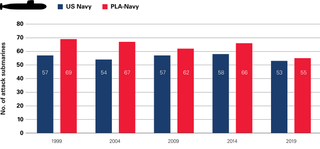

Figure 2: Key elements of China’s military modernisation

Since the mid-1990s, China has rapidly transformed its military from an antiquated Soviet-era institution into a sophisticated fighting force that is optimised to challenge American power projection assets. This has occurred on the back of stellar economic growth. Chinese defence spending rose by approximately 900 per cent between 1996 and 2018, permitting the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to sustain an impressive tempo of military modernisation across most key capability areas.48 Its advances in missiles, fighter jets, attack submarines and surface ships have been particularly striking in qualitative and quantitative terms. Although the PLA has yet to catch-up with the US military, Eric Heginbotham and other leading defence analysts point out that “the trendlines are moving against the United States across a broad spectrum of mission areas”.49 More to the point, because China would enjoy a home-court advantage in the case of a regional conflict, “it does not need to catch up to the United States to dominate its immediate periphery”.50

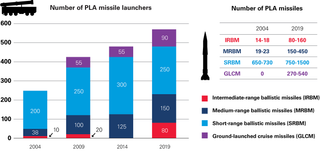

Figure 3: China’s missile inventory, 2004-2019

China’s increasingly favourable position in the regional balance of power is a product of the way Beijing has modernised and postured its armed forces. Crucially, the PLA’s development of anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) capabilities has been explicitly designed to challenge American military primacy by raising the costs and risks to US forces in the Western Pacific.51 Its massive investment in conventionally-armed ballistic and cruise missiles is the centrepiece of China’s “counter intervention” efforts.52 Over the past 15 years, the PLA has systematically increased, upgraded and extended the range of its inventory of missiles and launchers in what the US government has called “the most active and diverse ballistic missile development program in the world”.53 Although exact numbers are uncertain, the Pentagon estimates that the PLA Rocket Force now fields up to 1500 short-range ballistic missiles, 450 medium-range ballistic missiles and 160 intermediate-range ballistic missiles, in addition to hundreds of long-range ground-launched cruise missiles.54 These can strike targets throughout the First Island Chain and beyond, placing Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, the Philippines and Singapore well within China’s A2/AD threat envelope; and, in the case of the DF-26, extending this missile threat as far as the US territory of Guam, the location of major Air Force and Navy forward operating bases. China has also developed a specialised anti-ship ballistic missile, the DF-21D, which it recently test-fired from the mainland into the South China Sea, and is rolling-out a number of sea- and air-launched cruise missiles variants which will further extend the range and scale of its conventional missile threat.55 Looking to the future, China may well be ahead of the United States and its allies in developing advanced hypersonic missiles that would significantly worsen this threat environment.56

This growing arsenal of accurate long-range missiles poses a major threat to almost all American, allied and partner bases, airstrips, ports and military installations in the Western Pacific.57 As these facilities could be rendered useless by precision strikes in the opening hours of a conflict, the PLA missile threat challenges America’s ability to freely operate its forces from forward locations throughout the region. Alongside China’s broader A2/AD capabilities — including large numbers of fourth-generation fighter jets, advanced C4ISR systems, modern attack submarines, electronic warfare capabilities and dense arrays of sophisticated surface-to-air missiles — it permits the PLA to hold US and allied expeditionary forces at risk, preventing them from operating effectively at sea or in the air within combat range of Chinese targets.58 Following Beijing’s construction of a network of military outposts in the South China Sea that can support sophisticated radars, missile batteries and forward-based aircraft, the A2/AD threat is further intensifying in this critical waterway.

Figure 4: China’s growing missile threat to US bases and regional access locations

Preventing a Chinese fait accompli to preserve regional order

China’s formidable military power within the First Island Chain could have dire consequences for the regional order. This is because it provides Beijing with the coercive leverage it would need to quickly seize coveted territory or overturn other aspects of the status quo by pursuing a fait accompli strategy. Referring to the ability of a challenger to achieve its revisionist objectives before a defender or its partners can mobilise sufficient forces to respond, strategists are increasingly worried that China might accomplish a fait accompli by launching a limited war or “grey zone” operation under the cover of its A2/AD umbrella.59 At the most ambitious end of the spectrum, Beijing may attempt to reunify Taiwan by force — either through a direct assault, blockade, or some kind of hybrid attack involving kinetic, cyber and political warfare — exploiting surprise and local military superiority to its advantage.60 Similarly, and more plausibly in the near-term, the PLA might be emboldened to seize smaller targets such as the Japan-administered Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands in the East China Sea, features belonging to US allies or partners in the South China Sea like Scarborough Shoal and parts of the Spratly Islands, or Japanese territories along the First Island Chain, particularly in the Ryukyu Islands archipelago.61 In all these scenarios, Beijing’s aim would be to strike first to secure longstanding political goals or strategically valuable objectives before the United States can do anything to stop it.

Asymmetries in power, time, distance and interest would all work against an effective American response. Under present-day US posture in the region, most American and allied bases and forward-deployed ships, troops and aircraft would struggle to survive a PLA salvo attack, and would be initially forced to focus on damage limitation rather than blunting the thrust of a Chinese offensive.62 American forces that are able to operate would be highly constrained in the early phases of a crisis — lacking air and naval dominance, outnumbered by their PLA equivalents and severely challenged by the loss of enabling infrastructure, like functioning airstrips, fuel depots and port facilities, all of which would be at least temporarily degraded by precision strikes.63 Reinforcements from outside the A2/AD threat envelope would take considerable time to arrive from Hawaii or the US west coast and, as former Commandant of the US Marine Corps General Robert Neller has warned, they would first “have to fight to get to the fight”.64 Although the United States would probably — but not certainly — prevail in an extended war, escalation at this point would be enormously costly and dangerous. Herein lies the nub of a fait accompli: Because America’s interests in the security of its allies are “fundamentally secondary” to its own survival, and arguably less tangible than the core interests Beijing has at stake in many of these flashpoints, Washington may ultimately wager that intervention is not worth the candle.65

The broader ramifications of a Chinese fait accompli would be devastating for the Indo-Pacific balance of power and the stability of America’s alliance and partner network. In a direct sense, China’s seizure of strategic locations along the First Island Chain, such as key nodes in Japan’s Ryukyu Islands archipelago, would provide the PLA with significant military advantages. These could include: Bolstering its ability to threaten US and regional forces, enhancing its capacity to project power into the East China Sea and over Taiwan, and isolating Japan in a crisis from its security partners to the southwest.66 At the diplomatic level, the failure to prevent a Chinese attack on allied territory would exacerbate rising concerns about America’s capacity and willingness to act as a security guarantor in the region.67 Indeed, the mere fact that Washington might have to rely on military escalation and protracted conflict to defeat Chinese aggression is already eroding the credibility of its security assurances in certain quarters.68 The flow-on effects of uncertainty about American security commitments will vary according to countries and crises; but may well erode the willingness of allies and partners to support, sustain and contribute to upholding the US strategic position in the region — particularly if they think this exposes them to other forms of coercion by Beijing.69 This would further accelerate the unfavourable shift against America in the evolving balance of power.

By refocusing on a strategy of deterrence by denial and working to directly defend against a PLA attack, the Pentagon aims to avoid this chain of events. The logic of its new warfighting approach is sound: As China’s “theory of victory” is premised on its ability to employ limited force to achieve quick strategic payoffs and splinter regional alliance cohesion in the process, it follows that anything which makes this opportunistic course of action more dangerous is likely to give Beijing pause to think twice.70 Accordingly, the NDS calls for a layered approach to actively defending against prospective Chinese aggression. This includes “contact” forces to compete below the threshold of armed conflict; a resilient layer of “blunt” forces to “delay, degrade, or deny” a fait accompli by inflicting significant costs on attackers and preparing the battlespace for reinforcements; and a “surge” layer of “war-winning forces” that would later flow into the theatre to tilt the balance and manage escalation.71 It is, in many respects, a return to the kind of denial strategy that the United States employed during the Cold War in Europe to deter numerically superior Soviet forces from launching limited land grabs around its periphery.72 Crucially, like its successful forebear, deterrence by denial in the Western Pacific does not depend on local military superiority or all-domain dominance to succeed.73 Provided that America’s forward-deployed assets can weather a PLA assault and degrade its attacking forces to the point where Beijing — rather than Washington — is faced with the unappealing prospect of dangerous escalation, US and allied forces could deter the outbreak of violence even in the absence of military primacy.74

Implementing this strategy, however, will not be easy or cheap. On the contrary, it will require major changes to the US military’s force structure, regional posture and concepts of operations, only some of which are currently in train. Above all, the Pentagon will need to increase the “lethality” and “resilience” of its forward-deployed forces to enable them to “survive, operate and win” inside China’s A2/AD threat envelope.75 As RAND analyst David Ochmanek and other strategists have explained, some of the requirements will include: Advanced air, sea and submarine assets that can exploit stealth and long-range strike to rapidly neutralise PLA attacking forces, air defences and C4ISR systems; larger stockpiles of long-range standoff munitions, including ground-based artillery, to hold aggressors at risk in the early stages of combat; expendable drones and other low-cost assets to ensure situational awareness and deny it to opponents; and distributed basing arrangements, decoys and point defences to bolster the resilience and agility of US and allied forces.76 All this will need to be stitched together with new operational concepts — notably missing in the unclassified NDS, but under development in the Pentagon and wider defence community — to conceptualise how America will be able to conduct this new way of war and thereby strengthen deterrence in the Indo-Pacific.77 This places a premium on costly efforts to modernise the Joint Force, research and develop cutting-edge capabilities, and test new concepts through tailored wargames and experimentation.

“Without substantial and sustained increases in investments in new equipment and operating concepts, the credibility of US security guarantees to allies and partners in East Asia will continue to erode”.David Ochmanek, former Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Force Development.[78]

The Pentagon will also need to manage its forces differently to successfully implement a credible denial strategy against a great power like China. In contested parts of the Indo-Pacific, this means recalibrating America’s military presence to prioritise the “warfighting ability” of forward-deployed forces ahead of the reassurance of allies and partners.79 Although this may involve politically difficult decisions — such as reducing the footprint of vulnerable assets like aircraft carriers, or dispersing large concentrations of US forces from parts of Japan to locations further afield — such changes are critical to fielding a more survivable and therefore credible Joint Force. Globally, the trade-offs required will demand even more strategic discipline. Given the stresses of preparing for a possible conflict with China — in terms of cost, modernisation, readiness and training, etc. — the Joint Force will have to scale back other responsibilities, particularly in secondary regions like the Middle East. This is what the architects of the NDS mean by “prioritizing” great power competition.80 Rather than expending high-end resources and military readiness on strategically insignificant missions — such as using F-22s and B-1 bombers to conduct strike operations against ISIS targets — the Joint Force will need to conserve its strength for developing, exercising and demonstrating the ability to hold the line against China in the Indo-Pacific.

America’s superpower mindset and the problem of strategic prioritisation

It is far from clear that Washington has the strategic discipline and political will to make the difficult trade-offs that a strategy of prioritising great power competition with China requires. This is the central challenge the Pentagon faces in implementing the National Defense Strategy in an era of strained resources and proliferating global threats. The problem is not that decisionmakers disagree with efforts to counter the burgeoning China challenge. On the contrary, there is a hardening bipartisan consensus in Washington that views China as the most serious long-term threat to America’s global interests and supports the NDS’ emphasis on bolstering conventional deterrence vis-à-vis China and Russia.81 The problem is that disagreement exists within the foreign policy establishment over whether and how the United States should pare back its other global commitments in order to focus defence resources on the Indo-Pacific.

It is far from clear that Washington has the strategic discipline and political will to make the difficult trade-offs that a strategy of prioritising great power competition with China requires.

At the heart of this dilemma is the persistence in American political and foreign policy circles of an outdated “superpower mindset” that regards the United States as sufficiently endowed in economic and military strength to not have to make strategic trade-offs.82 Those adhering to this primacist school of thought fundamentally reject the idea that Washington should limit its defence strategy and liberal order-building agenda in order to conform with present-day resource constraints.83 One of the rationales for this position is the conventional wisdom that America’s superpower status hinges on its ability to prevail in at least two simultaneous “major regional contingencies”, in addition to prosecuting a wide array of less demanding global security tasks.84 The 1997 Quadrennial Defense Review, a precursor to the NDS, defined this strategic bandwidth as “the sine qua non of a superpower”.85 And as the international security landscape deteriorated over the intervening 22 years, leading voices on both sides of the political spectrum have called for sustaining or increasing America’s capacity to fight multiple adversaries at once — even as the Department of Defense has found the tempo of counterinsurgency and state-building operations to be increasingly debilitating in light of enduring budget constraints.86 This mainstream commitment to “reinvesting in primacy”, to paraphrase Hal Brands and Eric Edelman, is seen as essential to sustaining America’s position as the defender of a vast liberal order and global network of allies and partners.87 Crucially, its adherents urge Washington not to make choices between preparing for strategic competition with China and Russia, deterring rogue states like Iran and North Korea, combating global terrorism, fighting insurgents or promoting democracy in post-conflict states.88

This mindset is alive and well in Washington today, even among those who support the NDS and its elevation of great power competition to the top of America’s strategic priorities. Speaking at West Point earlier this year, Vice President Mike Pence laid out an expansive vision for America’s future military engagements, telling a cohort of graduating cadets that “it is a virtual certainty” they or their peers “will fight on a battlefield for America” in places as diverse as Afghanistan, Iraq, North Korea, the broader Indo-Pacific, Europe and the Western Hemisphere.89 While these remarks are not striking by the normal standards of Washington’s interests, coming from the administration’s leading public voice on the need to “take decisive action” against China’s efforts to undercut America’s global pre-eminence, Pence’s comments belie the inherent difficulty in trying to maintain strategic discipline.90

In fact, for a sizable majority of current and former officials, lawmakers, military leaders and think tank analysts, the Pentagon’s new focus on great power competition is viewed as an additional task for the Joint Force to manage alongside — not instead of — its other global commitments.91 Contending that the United States faces mounting threats to its global interests and those of its allies and partners, many hold that the so-called “4+1 framework” for focusing American defence strategy — namely: Russia, China, North Korea, Iran and transnational terrorism — remains an appropriate baseline assumption for the day-to-day demands that the Joint Force must manage, even if China now sits at the top of this list.92 For instance, while US lawmakers over the past 18 months have shown growing concern for the “pre-eminent” challenge China presents, many still see Russia as the most urgent threat, oppose troop withdrawals from Afghanistan and Syria, worry about premature détente on the Korean Peninsula, and are divided along partisan lines regarding the threat posed by Iran.93 Likewise, the US military’s combatant commanders for Europe, the Middle East, Africa and South America continue to emphasise the severity of threats emanating from their geographic areas of responsibility — including by highlighting the global scope of malign activities by China and Russia that warrant greater resources; and, in the case of US Central Command Commander General Joseph Votel, arguing that the NDS does not foreshadow a “wholesale shift in emphasis away from the Middle East and Central Asia regions”.94

Even the bipartisan panel of defence experts on the National Defense Strategy Commission, all of whom agree that “major power competition [with China and Russia] should be at the center of the department’s strategy”, have accused the Pentagon of “under-resourcing” other threats to US security interests. Epitomising America’s superpower mindset, they conclude: “Because the United States remains a global power with global obligations, it must possess credible combat power to deter and defeat threats in multiple theatres ... and near-simultaneous contingencies”.95

While the US military is, to be sure, capable of undertaking multiple global responsibilities at once, the sheer number and magnitude of the tasks it is being called on to address poses a severe and ongoing problem of strategic insolvency. Reigning in the scope of America’s expansive grand strategy will be a fraught — and probably insurmountable — policy challenge, given the vested political, diplomatic and institutional interests that lie behind Washington’s longstanding global commitments. For instance, as analysts Rick Berger and Mackenzie Eaglen point out, the call by supporters of the NDS to scale back security commitments to the Middle East is “outside the mainstream of American foreign policy”, variously opposed by politicians, the general public and much of the national security establishment.96 Similarly, suggestions that the Pentagon curtail the “symbolic” deployment of forces to allied countries to “assure” them of American security commitments, or that it accept greater risks in “lower priority” regions like the Middle East by undertaking operations with less sophisticated military assets, are also likely to encounter significant push-back.97 Although much will depend on the way that the Department of Defense “right-sizes” the Joint Force to balance core and peripheral mission sets, there are few reasons to be optimistic about Washington’s ability to quickly or significantly reorient the strategic ship of state to truly prioritise the Indo-Pacific ahead of other regions.

In fact, recent history shows that the Indo-Pacific has actually been short-changed insofar as targeted investments in regional security initiatives are concerned. Since 2015, American deterrence efforts in Eastern Europe and combat support efforts in the Middle East have received large-scale funding packages through the Pentagon’s annual budget, whereas comparable initiatives for the Indo-Pacific have been absent or under-resourced. Setup in the wake of Russia’s annexation of Crimea, the European Deterrence Initiative received US$16.5 billion through FY2019 to bolster military exercises with partner states and strengthen US defence facilities, presence and rotations in the region.98 Meanwhile, the Iraq, Syria, and Counter-ISIS Train and Equip Fund and the Afghan Security Forces Fund received a combined US$28.94 billion to support the burgeoning counterinsurgency and counterterrorism abilities of America’s regional partners.99 By contrast, the Indo-Pacific during the same timeframe received just US$259,000 through the Maritime Security Initiative for partner assistance and training in the wake of Chinese assertiveness in the South China Sea.100 Even if one counts a number of smaller defence initiatives in the Indo-Pacific theatre and the newly-established Asia Reassurance Initiative Act — which earmarks $1.5 billion per year for security programs — these regional funding discrepancies highlight the relative pull of American security interests in other parts of the world.101 As Eric Sayers, formerly of US Indo-Pacific Command, observes: “The issue remains that the scale of resource commitment to the region continues to fall short of the sizable objectives the US government has set for itself”.102

Since 2015, American deterrence efforts in Eastern Europe and combat support efforts in the Middle East have received large-scale funding packages through the Pentagon’s annual budget, whereas comparable initiatives for the Indo-Pacific have been absent or under-resourced.

The way that the Department of Defense has calibrated its budget requests since the NDS was released also indicates how a long-term strategy of prioritising great power competition with China could be undermined by preparations for other global contingencies. Rather than channelling the lion’s share of major new investments into next-generation military capabilities for future high-end warfighting needs, the FY2019 and, to a lesser extent, FY2020 requests over-emphasised restoring readiness, preparing for near-term military operations, and maintaining the overall size of the force.103 Both also allocated broadly consistent levels of funding across the military services, even though a strategic focus on great power competition in the Indo-Pacific would likely favour the Navy and Air Force.104 As budget expert Susanna Blume explains, these choices are out of sync with the NDS’ objective to prioritise capability over capacity.105 While significant investments were made in areas conducive to the strategy — including modernisation, research and development, and the procurement of advanced munitions and autonomous systems — both budgets spread resources more evenly between capability, capacity and readiness than supporters of the NDS expected.106 This belies a reticence to make hard strategic choices. Crucially, it signals that decisionmakers are unwilling to accept near-term risks to America’s ability to respond to multiple global contingencies, in return for honing its warfighting edge to deter China in the future.

In the absence of Washington’s ability or willingness to scale back its ongoing global commitments, the only sure way of resourcing the Pentagon’s strategy to restore conventional deterrence vis-à-vis China is to increase the size of the defence budget. This is the preferred course of action for those who favour a return to primacy and consolidation of America’s superpower status.107 It is, however, a worryingly unrealistic and imprudent aim. Although exact numbers are hard to predict and vary between analysts, many agree with the National Defense Strategy Commission’s ballpark judgement that 3-5 per cent annual growth above inflation would be required for the United States to combat the threats posed by China, Russia, Iran, North Korea and global terrorism at acceptable levels of strategic risk.108 One assessment by RAND puts the cumulative gap between America’s current defence spending projections and the requirements of this expanded strategy at more than US$500 billion by 2027.109 Such increases are highly unlikely to happen and even less likely to be sustained. Not only does the administration’s FY2020 budget request fall just outside of its own minimum target at 2.8 per cent real growth, but the wider politics of the US defence budget are likely to complicate and constrain available resources for the foreseeable future.

Part 2: Defence budget constraints

The US defence budget is under mounting pressure. America’s armed forces need sustained and predictable growth in financial resources in order to implement the National Defense Strategy. But achieving this objective will require a marked and ongoing shift in the political status quo that has taken hold in Congress. The impact of the Budget Control Act’s legislative caps on defence spending over the past decade, coupled with repeated funding delays and budgetary uncertainty, has hobbled America’s ability to effectively respond to a shifting strategic landscape in the Indo-Pacific. Although the past few years have seen promising steps towards rectifying these shortfalls, the reality is that the NDS remains underfunded.

Political trends within Congress and long-term fiscal challenges facing the United States suggest that the misalignment between American strategy and resources is likely to continue. Growing ideological polarisation between Republicans and Democrats over national spending priorities, coupled with declining public support for higher military spending, will likely impede the political consensus required to achieve 3-5 per cent real growth in annual defence expenditure through 2023 as recommended by the National Defense Strategy Commission. The spectre of looming deficits and historically high levels of public debt will further complicate the process by which diverging partisan objectives can be resolved, constraining budget top lines into the future.

At the same time, key elements within the US defence budget itself are displaying worrying signs of becoming unsustainable. The defence dollar’s purchasing power is under strain from growing internal costs, while numerous accounts are ballooning above inflation such as military healthcare, compensation of personnel, maintenance of aging equipment and the acquisition of next-generation platforms.

Efforts to address these structural issues remain incomplete. Although recent increases to the US defence budget have started to rebuild the armed forces for strategic competition, America’s political and military leaders have continued to add missions, roles and responsibilities to an already overstretched Joint Force. Funding, meanwhile, has remained inconsistent. Continued unwillingness to confront politically difficult decisions regarding America’s national defence means that, based on present trends, the United States will face a deepening crisis of strategic insolvency.

America’s troubled defence budget

On 9 February 2018, President Donald Trump signed into law the biggest year-to-year increase in defence spending since 2003.110 News outlets and commentators were quick to declare the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (BBA) “a Pentagon budget like none before”,111 characterising the increase to defence spending as “the upper limit of what anyone thought was possible”.112 This language was not entirely hyperbolic: Congress defied years of convention by providing more funds for defence in the BBA than requested in the president’s budget, in an agreement that dwarfed the rate of past increases to Budget Control Act (BCA) spending limits by more than three times over.113 While previous legislative deals to soften the impact of the BCA had been relatively modest, the BBA added US$80 billion to defence spending in FY2018 and $85 billion in FY2019 — representing a real increase of approximately 11 per cent.114 This year Congress has passed another bipartisan spending deal to cover the remaining two years of the BCA. Under this agreement, spending on defence is set to reach US$738 billion in FY2020 and US$740.5 billion in FY2021, a comparatively modest increase that shrinks to a flatline with inflation from the following year.115

Both of these short-term political fixes, however, obscure longer-term barriers and evolving partisan dynamics in Congress that will prevent sustained and predictable budget increases of a similar scale in the future. Rather than heralding a new era for US defence spending, they illustrate an overdue attempt by legislators to offset some of the damaging results of spending limits imposed by the BCA. Importantly, they do not form a model for spending agreements following the expiration of these caps in 2021 and beyond.

Between 2011 and 2018, total spending on US national defence declined in real terms by 21 per cent.116 In the lead-up to the passage of the BBA, a targeted campaign by the late Senate Armed Services Committee Chairman John McCain (R-AZ) and then-House Armed Services Committee Chairman Mac Thornberry (R-TX) brought home the reality of America’s military readiness crisis to lawmakers, successfully linking defence spending cuts with a string of US Navy collisions at sea.117 Republican defence hawks were able to capitalise upon political momentum to raise spending in a crucial midterm election year, when their party had unified control of government and was keen to deliver a key election promise made by President Trump. Democrats, for their part, were motivated by a desire to deliver a “win” to their political base from a position of relative legislative weakness by demanding comparable increases to domestic spending in return for their support.118 Yet, even following his successful stewardship of the deal, Thornberry was quick to warn “it would be a mistake” to view the BBA as a silver bullet for the Pentagon, stating that “not everything is fixed because we have a substantial increase in one year” and quipping “the closer you look, the deeper the problems are”.119

While agreements have been reached to increase the resources available for America’s national defence, these funds represent a broader political compromise rather than a concerted effort to remedy the misalignment between resources and strategy.

Many of these problems are deeply ingrained. The US defence budget has faced significant downward pressure and decreased buying power over the past decade. As the National Defense Strategy Commission report shows, even factoring in the US$237 billion of cumulative defence funding added by the BBA and two previous budget deals in 2013 and 2015, BCA-imposed spending caps have still resulted in a net US$539 billion reduction in base budgets between 2012 and 2019, relative to former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates’ final spending plan before the BCA became law.120 While the US$700 billion of enacted defence spending resulting from the BBA in FY2018 was a significant increase from the previous fiscal year, growth in the budget’s top line to US$716 billion in FY2019 was on par with inflation and has by no means undone the damage of cumulative spending shortfalls since 2011.121

Worryingly, the most recent congressional budget deal continues this trend into the future. While agreement has once again been reached to increase the resources available for America’s national defence, these funds have been provided as part of a broader political compromise rather than a concerted effort to remedy the overall misalignment between resources and strategy. A statement released by the Democratic Congressional Progressive Caucus — a key voting bloc that ensured the bill’s passage in the House — stated that their support “does not address the bloated Pentagon budget, but it does begin to close the gap in funding for families, by allocating more new non-defence spending than defence spending for the first time in many years”.122

Put simply, recent developments in Congress have failed to achieve sustained real growth in the defence budget, illustrating the significant political barriers to achieving this objective and raising questions regarding the viability of similar deals moving forward. Following the passage of the BBA, Chairman of the House Armed Services Committee Adam Smith (D-WA) predicted that “the odds are, this is the largest the defence budget is going to be for, probably, about the next decade”.123 Smith’s prognosis is already becoming a reality. The Trump administration’s FY2020 “masterpiece” budget requested an increase of only 2.8 per cent in real terms over the Department of Defense’s enacted spending for FY2019,124 with growth in the administration’s Future Years Defense Program through 2023 annualising to just 2.1 per cent.125 While this year’s spending deal provides another two years of budget predictability for the Pentagon, it also fails to implement the administration’s requested top line of US$750 billion — falling short of the National Defense Strategy Commission’s recommended 3-5 per cent growth at precisely the time that the department’s internal costs are predicted to rise.126

The congressional budget process and Budget Control Act of 2011 |

|

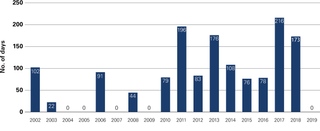

The US Constitution invests Congress with the “power of the purse” and the responsibility to determine federal spending through its budget process. Discretionary spending — including for national defence — is provided by annual appropriation bills and forms the focus of congressional efforts to fund the federal government. Mandatory spending — including entitlement programs such as Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid — is generally determined by existing statutory criteria and is provided in permanent or multi-year appropriations.[^127] Since the passage of the Gramm-Rudman-Hollings Act in 1985, Congress has periodically imposed budget enforcement mechanisms such as “caps” on discretionary spending in order to achieve broader fiscal objectives. Between FY2009 and FY2012, reduced tax revenues and economic stimulus undertaken in response to the global financial crisis resulted in federal deficits averaging their highest percentage of GDP since the Second World War.[^128] Republicans and Democrats in Congress were split over the amount and process by which the deficit should be reduced. In 2011, this partisan discord converged with the need to increase the federal debt ceiling. Following their electoral success in the 2010 midterms, newly emboldened Tea Party Republicans sought deficit reduction solely through decreased federal spending, while Democrats pressed for tax increases to offset some of the need for these austerity measures.[^129] The impasse put the US economy on the brink of a default and fiscal crisis, eventually forcing President Barack Obama to sign the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA) in August after extended negotiations with congressional leaders. In return for a US$2.1 trillion increase to the debt limit, the BCA amended the Gramm-Rudman-Hollings legislation to reinstate spending limits on discretionary spending between FY2012 and FY2021, creating US$917 billion of projected savings over the ten-year period.[^130] It also established a bipartisan “super-committee” to devise further savings of at least US$1.2 trillion. When the committee failed to agree on additional deficit reduction measures, automatic spending-cut provisions included within the BCA known as sequestration went into effect in March 2013, resulting in US$50 billion of across-the-board cuts for defence and non-defence spending. Congress was able to offset some of these cuts through a subsequent spending deal in 2013 and has repeatedly voted for deals to raise the BCA caps through spending agreements thereafter. If Congress had failed to reach another deal this year, approximately US$71 billion of automatic budget cuts to defence spending and US$55 billion to non-defence spending would have gone into effect in January 2020.[^131] Spending limits imposed by the BCA have been a source of political contestation since their enactment.[^132] Proponents of the legislation argue that the provisions help restrain rising debt and deficit levels. However, members of the defence establishment have taken a different approach, arguing that such reductions “present a grave and growing danger to our national security”.[^133] |

Figure 5: Changes to Budget Control Act limits on national defence

Congress and the politics of the defence budget

In recent years, congressional dysfunction has repeatedly created political fixes for America’s national defence at the expense of its broader strategic objectives. Debates over the size and shape of the US defence budget are necessarily filtered through competing social, political and electoral considerations within Congress. This process, however, has become increasingly difficult for major parties and individual lawmakers to navigate as polarisation and ideological hardening has grown in the national legislature. While partisan politics and deal-making are inherent features of America’s democracy, the growing extent to which these elements have been used as tools of electoral advantage has derailed traditional budgetary timelines and hindered targeted and long-term planning by

the Pentagon.134

The federal budget process is designed to adhere to an orderly schedule, commencing with the president’s annual budget request each February. After consideration by relevant committees, Congress is tasked with passing a series of 12 spending bills that fund various agencies and activities of the federal government, including the Department of Defense. These appropriations bills require a supermajority of 60 votes to pass the Senate, meaning that bipartisan cooperation and trade-offs are vital. But the traditional point of friction in the US political system that is meant to elicit legislative compromise — that between Congress and the executive — has increasingly drifted towards partisan clashes within the legislative branch. As a result, adherence to budget processes and deadlines has declined in recent congresses as both parties have increasingly used budget chokepoints to force policy adjustments from the opposing side.135 Because of its “must-pass” nature, disputes over the federal budget have regularly become a key vehicle for lawmakers from both major parties to voice ideological disagreements, leading to a dysfunctional culture of brinkmanship, crisis policymaking and legislative gridlock.136

“As hard as the last 16 years of war have been on our military, no enemy in the field has done as much to harm the readiness of the US military than the combined impact of the Budget Control Act’s defense spending caps, worsened by operating for 10 of the last 11 years under continuing resolutions of varied and unpredictable duration”.Former Secretary of Defense James Mattis, 6 February 2018

Funding for the Pentagon and related programs comprises more than 50 per cent of annually appropriated federal spending and is heavily shaped by broader contestation over national priorities. The concurrent impact of BCA caps on both defence and non-defence spending has exacerbated existing partisan disagreement over the appropriate allocation of resources within the overall budget, creating delayed timelines for the Department of Defense. For example, stalled negotiations over setting new BCA caps forced the Pentagon to operate under a continuing resolution for an average of 138 days between 2011 and 2018.137 The cumulative effect of politicisation on the defence budget was highlighted by former Secretary of Defense James Mattis in 2018, when he declared: “As hard as the last 16 years of war have been on our military, no enemy in the field has done as much to harm the readiness of the US military than the combined impact of the Budget Control Act’s defense spending caps, worsened by operating for 10 of the last 11 years under continuing resolutions of varied and unpredictable duration”.138 But while the BCA has introduced unique political hurdles into the congressional appropriations process, partisan disagreement over national spending priorities is set to remain front-and-centre in budget debates, even following the scheduled expiration of the caps in 2021.

What are continuing resolutions and how do they impact the Department of Defense? |

|

Congress has often struggled to deliver its 12 regular appropriation bills on time — before the start of each fiscal year — since major reforms to the budget process in 1974. Instead, the US legislature has become reliant upon measures known as continuing resolutions — stop-gap spending extensions that prevent government shutdowns by preserving the previous year’s funding levels for a negotiated period. The deterioration of regular order in Congress has meant that the US federal government is often funded through lengthy continuing resolutions or omnibus appropriations measures that combine the 12 separate spending categories into one must-pass bill.[^139] Over the past decade, appropriations for the Department of Defense have been significantly impacted by this trend. Continuing resolutions serve a political purpose in that they provide Congress with a longer window to reach budget agreement.[^140] However, they impose substantial military and defence costs on the Pentagon due to the lack of flexibility, budget uncertainty and the inefficiencies they create. Continuing resolutions restrict how funds can be spent by the department and block movement between accounts through traditional reprogramming. In practice, this means a freeze on hiring, contracts and the initiation of new programs that were not authorised and appropriated for in the previous fiscal year.[^141] These constraints force the Pentagon’s leadership to focus on the short rather than long term. In March 2017, then-Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Joseph Dunford testified that “eight years of continuing resolutions and the absence of predictable funding has forced [the Department of Defense] to prioritise near-term readiness at the expense of modernization and advanced capability development”.[^142] Further, Congress’ inability to provide funding in a timely or predictable basis has prompted inefficient, “use-it-or-lose-it” spending and impacted long-term modernisation programs.[^143] |

Figure 6: Number of days the Pentagon has operated under a continuing resolution since 2002

Partisanship, polarisation and barriers to the National Defense Strategy