Executive summary

- The 2023 Defence Strategic Review (DSR) acknowledged that Australia no longer enjoys the regional technology edge once afforded by its alliance with the United States, and also affirmed the end of a 10-year warning time for major conflict in the Indo-Pacific.1 With both Australia and the United States facing a darkened strategic environment and weakened technology advantage, the demand for innovative capabilities and the need to cooperate to deliver these at pace has scarcely been more important.

- It is from this logic that Australia, the United States and the United Kingdom announced the AUKUS partnership in 2021, to transform trilateral defence cooperation across 2 lines of effort: Pillar I conventionally armed, nuclear-powered submarines and Pillar II advanced capabilities. These include undersea capabilities; quantum technologies; artificial intelligence and autonomy; advanced cyber; hypersonic and counter-hypersonic capabilities; electronic warfare; and innovation and information-sharing working groups.2

- Pillar II has a distinct focus on dual-use capabilities, or technologies with application in both military and commercial contexts and has highlighted the importance of integrating the commercial technology sector — comprising start-ups, small-to-medium enterprises (SMEs), research institutions, private capital funders, and other non-traditional defence suppliers — into the defence industrial base to comprise a broader national security innovation base.3

- The Ukraine war further emphasised the need to rapidly deliver cutting-edge commercial technology such as drones to observant governments in Australia, the United States and the United Kingdom. Notwithstanding this strategic urgency, the commercial technology sector remains largely disincentivised from engaging in the defence market, including with respect to AUKUS.4

- This report identifies 3 obstacles to broader commercial technology sector participation: the defence market’s weak commercial rationale for dual-use firms, or the ‘market thesis’; financing challenges; and acquisition and procurement issues. It then explores why and how these represent barriers to integrating the commercial technology ecosystem into the defence industrial base and assesses existing Australian and US responses to these challenges — which have scope to go much further.

- Finally, the report outlines how greater cooperation between Australia and the United States could alleviate these 3 challenges, drawing a clear line between this imperative and the success of initiatives like AUKUS Pillar II.

With both Australia and the United States facing a darkened strategic environment and weakened technology advantage, the demand for innovative capabilities and the need to cooperate to deliver these at pace has scarcely been more important.

Recommendations

This analysis, supported by consultation with officials and experts across the defence innovation ecosystems in Australia and the United States, has led to the development of five targeted recommendations, designed to be delivered at the bilateral and trilateral level where relevant to AUKUS Pillar II.

Market thesis

- The United States and Australia should emulate the success of the US’ Blue Unmanned Aerial System (Blue sUAS) program to improve the defence market thesis for dual-use technology firms. Blue sUAS aggregates the US Government’s purchasing power to increase commercial drone supply for the Department of Defense (DoD).5 Emulating its success would involve standardising requirements for specific technologies within alliance initiatives, such as AUKUS Pillar II. It would significantly increase the collective purchasing power of governments, and therefore incentives for commercial technology sector engagement with the defence market.

- To demystify pathways to contracting and scale, Australia and the United States should build on existing efforts in the AUKUS Advanced Capabilities Forum and supplement this with US-India Defence Acceleration Ecosystem (INDUS-X)-style industry and academia workshops.6 INDUS-X facilitates bilateral partnerships and innovation between defence and dual-use stakeholders in both countries.7 Such workshops would strengthen the relationship between the government and the commercial technology ecosystem and encourage more frequent dialogue and information sharing about contracting opportunities, pathways to scale, and effective relations with the government. Workshops could be hosted by US and Australian universities to alleviate government workload.

Financing

- In partnership with the United Kingdom, Australia and the United States should explore establishing a multi-sovereign public-private innovation fund for Pillar II advanced capability development. This would send a stronger demand signal to private investors and provide a bedrock of capital and associated financial expertise for start-ups and other commercial technology entities interested in producing capability for AUKUS Pillar II. This fund could be modelled off the NATO Innovation Fund — a multi-sovereign venture capital fund that supports the fielding of dual-use technology solutions in NATO countries. It would build on existing efforts to harness private capital for Pillar II through the AUKUS Defence Investors Network.8 The fund should also establish mechanisms to verify trusted capital providers to ensure participating investors do not have links to adversarial nations.9 A suitable place to start would be leveraging work already underway in the US DoD’s Trusted Capital Digital Marketplace program.10

Acquisition and procurement

- To improve the pace at which innovation proposals can be assessed, the Australian Government’s Advanced Strategic Capabilities Accelerator (ASCA) and the US Government’s Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) should direct proposals related to AUKUS Pillar II to a common pool, which could be managed under the existing Pillar II Innovation Working Group.11 Acquisition and sustainment staff from the Australian Department of Defence’s Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group (CASG), the US Department of Defense’s Acquisition and Sustainment Office, and the UK Defence Equipment & Support organisation (DE&S) engaged with Pillar II could then provide surge capacity to filter through these at pace.

- Australia and the United States should share best practices for integrating commercial ways of working into acquisition and procurement processes. In particular, ASCA would benefit from gaining insight into DIU’s Immersive Commercial Acquisition Training Program and the mechanisms DIU employs to incentivise ‘dual fluency’ talent — those with experience in national security but also in the technology sector or the military — into its workforce. This acknowledges the material benefits such integration has on defence innovation outcomes.12

Introduction

Australia’s 2023 Defence Strategic Review and the US’ 2022 National Defense Strategy share a darkened outlook for the risks of major conflict in the Indo-Pacific region.13 Both strategies underscore the changing nature of warfare and the importance of developing asymmetric advantage — the ability to set strength against adversarial weakness — in key technology areas.14 The Ukraine war has only increased the urgency of this mission and highlighted the strategic advantages of utilising commercial technology like drones and satellites for reconnaissance and surveillance.15

The Australian Government’s recently released 2024 National Defence Strategy committed to strengthening defence innovation engagement with the United States.16 Likewise, the 2023 US National Defense Industrial Strategy established the need to “fortify alliances to share science and technology” and to establish new mechanisms for “sharing technologies and applications of scientific knowledge with other allies and partners.”17

At the official level, ministerial and departmental leaders are aligned on the importance of better integrating the commercial technology ecosystem into the defence industrial base to deliver disruptive capabilities to their militaries. Leading US DoD officials, including the Director of the Defence Innovation Unit have noted the need to be a better partner to the commercial technology sector, which is leading progress in 11 of the DoD’s 14 critical technology areas.18 Similarly, upon establishing ASCA, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Defence Richard Marles, and Minister for Defence Industry Pat Conroy, emphasised cooperation with the broader commercial technology ecosystem to deliver advanced capability to the Australian Defence Force (ADF) at pace.19 This organisation was launched in large part to operationalise Pillar II advanced capabilities.20 Statements such as these therefore underscore the importance of the commercial technology ecosystem to AUKUS Pillar II.

Despite these examples of collaboration and ministerial and bureaucratic alignment on the need to better integrate the commercial technology ecosystem into the defence industrial base, neither Washington nor Canberra are easy customers for the commercial technology ecosystem.

Outside of government, defence-relevant commercial technology breakthroughs and successful collaborations between commercial technology entities and the defence establishment have underscored the importance of expanding the national security innovation base. In a 2023 United States Studies Centre report, authors William Greenwalt and Tom Corben noted technology advancements in the commercial sector have outpaced innovation within the US Government for decades.21 In that report, the authors pointed to the SpaceX Falcon 9 Project and the adoption of StarLink technology in the Ukraine war as powerful examples of advantages commercial technology can provide governments at “a fraction of the cost of the legacy defence innovation system.”22 Other examples, such as NVIDIA’s collaboration with the US DoD on machine learning and artificial intelligence are further evidence of the advantages the commercial technology ecosystem can provide to government. NVIDIA has recently signed a US$20 million AI deal with numerous US federal government agencies, including the DoD, which will deploy AI capabilities across government and digitally transform the military services.23

Despite these examples of collaboration and ministerial and bureaucratic alignment on the need to better integrate the commercial technology ecosystem into the defence industrial base, neither Washington nor Canberra are easy customers for the commercial technology ecosystem. There is a vast body of literature — especially in the US context — that documents the plethora of challenges the commercial technology ecosystem faces in trying to operate in the defence market.24 This includes financing challenges, regulatory and cyber security requirements, a weak market thesis, complex and lengthy acquisition and procurement processes, and domestic manufacturing issues.25

There are lessons here for the US-Australia alliance. Indeed, while there are vast differences between the Australian and US defence innovation ecosystems, their respective commercial technology sectors face similar barriers to entering the defence market. Furthermore, defence cooperation between the 2 countries has matured rapidly since the uptick in alliance force posture initiatives dating back to 2011,26 and amid a more recent push to better incorporate defence industrial and technology cooperation into the alliance’s robust deterrence agenda. Better integrating the commercial technology ecosystem into the 2 countries’ defence industrial bases will be essential to the success of those efforts. It is from this premise that the following explores opportunities for collaboration on 3 key aspects of this challenge: a weak market thesis, financing, and acquisition and procurement challenges.

Defining the challenges

Market thesis

For many firms in the broader commercial technology ecosystem, the market thesis for the defence sector in both Australia and the United States is not entirely compelling. The main reasons for this include: complex pathways to scalability and the questionable credibility of government demand signals; restrictive export controls which complicate selling commercial versions of a product; and limited market size which prevents economies of scale. Despite progress, the Director of the US Defence Innovation Unit has said that DoD’s demand signal to the commercial technology sector remains unclear.27 Likewise in Australia, non-traditional defence suppliers report challenges in identifying opportunities in the defence market.28 This is incredibly problematic for dual-use technology-focused initiatives like AUKUS Pillar II, as industry and investors are unable to gauge the level of risk they should shoulder, nor allocate an appropriate level of financial and human capital on the correct timeline. Taken together, these factors lead to a general sense of uncertainty about the defence market.29

Secondly, defence trade controls, such as the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR) and other US export regulations which capture dual-use technology like the Export Administration Regulations (EAR) and Australia’s own Defence Trade Controls Amendment Act, make it very difficult for firms to sell non-military versions of their products in the commercial market.30 Importantly, the well-documented and long-standing challenges that the ITAR presents for allied defence cooperation have also “disincentivise[d] collaboration on the next-generation of advanced military capabilities under Pillar II.”31 This is because the ITAR presents an onerous set of compliance burdens which are difficult for resource-constrained start-ups and SMEs to manage. These include but are not limited to: the risk of losing control over intellectual property to the US Government; financial and staffing costs required to comply with the ITAR; and the slow speed at which waiver license approvals are processed through the US bureaucracy.32

For many firms in the broader commercial technology ecosystem, the market thesis for the defence sector in both Australia and the United States is not entirely compelling.

Encouragingly, there have been recent signs of progress. On May 1 2024, the AUKUS partners announced a range of national-level regulatory reforms to harmonise defence trade controls between the 3 countries in the interests of creating an AUKUS defence free-trade zone. If implemented, these changes would streamline defence trade between the 3 countries by removing requirements for about 900 export permits, equating to A$5 billion annually from Australia to the United States and the United Kingdom. This would enable licence-free trade for over 70% of defence exports subject to the ITAR and 80% of exports subject to the Department of Commerce’s EAR from the United States to Australia.33 However, as some analysts have contended, these necessary and well-intentioned reforms may fail to protect AUKUS Pillar II technologies from legacy export control issues.34 This would mean that compliance costs and other challenges presented by export controls would continue to remain a powerful deterrent to the integration of commercial technology firms in the defence industrial base. Faced with the choice between being able to sell their technology in the commercial market versus the defence market, many firms would likely choose the former — despite the aforementioned licensing carveouts — due to compliance costs, legal risks involved, as well as the vast difference in market size and profitability.35

Finally, even if stakeholders in the commercial technology ecosystem choose to sell their products to the government, the size of their market is often restricted due to the unique equipment requirements of different arms of the military.36 Sometimes this is a necessity and rightly so, as military strategy should drive product requirements rather than the other way around. However, this prevents firms from being able to create economies of scale and therefore represents another barrier to the greater integration of the commercial technology ecosystem into the national security innovation base.

For Australia, the recent introduction of the Defence Trade Controls Amendment Act may well exacerbate these tensions, as firms and their founders must adjust to more complicated compliance requirements, which could prevent the sale of non-military versions of their products in commercial markets altogether.37 This would be a fatal blow to the main thrust of initiatives like AUKUS Pillar II and may force some dual-use firms involved in the defence and commercial sectors to rethink the viability of their strategy.38

Financing

Financing represents a major challenge to commercial technology start-ups and SMEs interested in working in the defence sector. Neither the Australian nor US Governments are sending an adequate demand signal to private capital to invest more significantly in defence innovation, nor are current levels of government funding sufficient to support the level of defence innovation required by initiatives like AUKUS Pillar II on their own. For commercial technology entities, winning a lucrative contract with the Australian or the US Department of Defence is the end goal, but the precarious path to get there requires financial support from venture capital (VC) or (less often) other private investment entities such as private equity, superannuation firms or family offices. In the Australian context, the private capital sector and the Department of Defence have until now largely operated independently of one another, as the department had limited strategic reason for external funding to bolster capability.39 However, even in the United States where VC and other private capital entities have more established connections with the Pentagon, they have traditionally viewed the defence market with a degree of trepidation. This has partly been due to a poor investment outlook with poor exit options (such as mergers and acquisitions) for investors. This is because defence companies must focus on extracting as much value as possible out of every government contract. Defence technology is also more often concerned with hardware ventures, which require much greater capital expenditure to scale than software ventures.40

Complicating matters further, VCs and other private investors must weigh up environmental, social, and governance (ESG) standards; these are corporate reporting requirements that assess a firm’s impact on the environment, society, and its stakeholders.41 They must also gauge their level of comfort with the Australian or US Government being the primary customer of their ventures. This includes consideration of whether sufficient political will exists to sustain contracts over multiple years, as well as the government’s ability to award contracts at the scale required for venture investments to be worthwhile.42 This has been a distinct concern in Australia as the Department of Defence has a history of cancelling contracts and is also a small market in comparison to other more lucrative sectors of the economy.43 To their credit, both the US and Australian Governments offer several financial solutions for start-ups and SMEs on the path to winning a larger defence contract. These include smaller seed grants, financial partnerships, and investor and start-up match-making, all of which will be analysed in greater detail in the following section.44

Solutions notwithstanding, federal resourcing itself is also a considerable restraint on defence innovation. For Australia, its economic size is a stark hand break on the amount of money it can dedicate toward defence innovation line items. For example, despite the 2024 National Defence Strategy previewing a A$16-21 billion commitment over the next decade, including A$3.6-3.8 billion for ASCA, the organisation favours a co-production and co-funded approach. This ideally requires the firms ASCA engages with to front 50% of the cost themselves.45 This is a significant capital investment request for firms who may not have complete confidence in their customer to pull through nor capital of that scale to contribute in the first instance.

Meanwhile, the US’ defence innovation ecosystem continues to be hamstrung by the Defense Department’s two-year budget model, known as the Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution (PPBE) system. The PPBE apportions financial resources among the department, military, and related agencies, and constitutes the DoD’s input into the annual presidential budget request.46 It is problematic because of its inflexibility and length. The 2-year cycle of the PPBE may have been sufficient in an era in which the department’s expenditure was skewed towards large and highly capital-intensive equipment such as air carriers. However, this time-intensive process is not well-suited to the rapid integration of advanced capability and often results in small and innovative companies being unable to sustain their operations whilst waiting for a government contract to be approved.47 Though the US Government is progressing several initiatives to build a private capital ‘funding bridge’ in support of this issue, the department’s funding structure is misaligned with the financial incentives of venture capital. Trae Stephens, co-founder of Anduril Industries said that whereas venture capital is raised in rounds occurring every 12-18 months, the US DoD’s process of including a firm in a draft budget proposal, to awarding that firm a contract can take up to 3 years.48

Acquisition and procurement

Both the Australian and US defence innovation ecosystems suffer from complex and lengthy acquisition and procurement processes that further disincentivise commercial technology firms from entering the defence market. The differences between aspects of the Australian and US acquisition and procurement systems mean that many of these are out of scope for this paper. This includes issues such as broader reform from single to multi-year procurement contracts in the United States.49 However, there are several common challenges Australia and the United States face which would benefit from a more collaborative approach, particularly if AUKUS Pillar II advanced capabilities are to be delivered trilaterally, as previewed by Australia’s 2024 National Defence Strategy.50 Common challenges include a cultural and bureaucratic aversion to risk within government, human capital shortages, and training and procedural challenges.

Both the Australian and US defence innovation ecosystems suffer from complex and lengthy acquisition and procurement processes that further disincentivise commercial technology firms from entering the defence market.

Firstly, both innovation ecosystems suffer to varying degrees from a bureaucratic and cultural aversion to risk that is antithetical to the spirit of innovation. The Australian Government has recognised the need for the Department of Defence and the Australian Public Service more broadly to reconceptualise their relationship to risk in the context of defence innovation.51 For government, this means embracing and rewarding risk-taking to keep pace with the strategic circumstances Australia faces.52 To be sure, a culture of risk-aversion exists within government for good reason: the sensible management of public funds. However, a previous USSC report found that the Australian Department of Defence must develop novel risk and reward processes, such as incentives and protection for department officials who demonstrate a willingness to ‘embrace failure,’ if advanced capability development is to occur on the required timeline.53

In the United States, the Department of Defense has less of an issue in this regard. This is partly because the Pentagon has a much larger budget, which allows for a comparatively more adventurous allocation of capital. The DIU is also arguably more advanced than ASCA in integrating commercial practices and attitudes into their acquisition and procurement models and benefits from the fact that its leader reports directly to the secretary of defence.54 Examples of ways in which commercial practices and attitudes have been integrated into the organisation include a focus on hiring ‘dual-fluency’ talent with significant private sector and military experience, and training acquisition staff on commercial procurement models. Unlike military models these primarily emphasise speed to contract.55 Despite this progress, bureaucratic processes and culture remain a hamper on defence innovation in both countries, and factors such as lengthy and complex contracting continue to frustrate greater integration of the broader commercial technology ecosystem.56 To survive and find a path to scale, start-ups and SMEs require greater consistency in speed to contracting, and the guarantee of a longer relationship with additional support from the DoD.57

Human capital challenges, including staffing constraints in both countries, also limit the speed at which DIU and ASCA can sort through innovation proposals, particularly those that are unsolicited in the case of the DIU, noting that ASCA does not accept unsolicited proposals.58 While this is a good problem to have, the risk is that promising technology is not harnessed, and the broader commercial technology ecosystem remains weary of the government as a partner. In the US’ case, the DIU under its new directorship has emphasised the imperative of adequately staffing the organisation. Moreover, DIU leadership has explicitly stated that staffing shortcomings have prevented the achievement of broader organisational objectives. Though the US Secretary of Defense has approved plans to resource DIU with more staff, it will take time for this to come into effect.59 Similarly, ASCA faces challenges in achieving adequate staffing levels, particularly amidst broader retention and recruitment shortfalls across the entire Australian Department of Defence.60

Finally, shortcomings in acquisition program manager training and expertise in both the DIU and ASCA can lead to gaps between what kinds of support the staff can provide partner firms and the type of engagement these firms need. For example, a 2023 report by the US Defense Innovation Board found challenges in communicating DoD’s investment processes were a major deterrent to greater commercial technology sector integration in defence.61 The report identified undertraining as the root cause, noting innovation outcomes would benefit from reformed program management training. This included acquisition staff improving their capacity to brief portfolio firms on “defence missions, IT, clearances, and other DoD-isms.”62 In the Australian case, defence acquisition and procurement has arguably suffered from having a lack of staff in government with private sector training and expertise, which can negatively affect the quality of government engagement during acquisition and procurement processes.63

Existing lines of effort

Australia and the United States face comparable challenges in broadening and deepening their national security innovation bases which cut across financing, market thesis, and acquisition and procurement thematics. To their credit, both countries have independently — and on occasion bilaterally or trilaterally — progressed initiatives to address these issues.

Australia

Following the release of the 2020 Defence Strategic Update, Australia announced several initiatives to address market thesis, financing, acquisition and procurement challenges commonly faced by start-ups and SMEs in the defence sector.

The market thesis

In July 2023, the Australian Government announced the A$240 million Defence Trailblazers program in partnership with the Universities of Adelaide and New South Wales, Boeing Defence Australia, Cisco and CAE Australia. The program aims to cultivate innovative sovereign capability by encouraging greater collaboration between research communities, defence industry and the Australian Department of Defence, and seeks to promote and shorten the commercialisation pipeline for promising initiatives.64 It is primarily focused on defensive hypersonics, cyber, robotics, artificial intelligence and space technologies. Of particular importance is the Defence Innovation and Commercialisation program, which promotes collaboration between industry, academia and experts to locate commercialisation pathways.65 The Defence Trailblazers initiative represents a concerted effort to create better incentives and pathways for non-traditional industry players in the defence market. While it is likely too early to gauge the impact of the Defence Trailblazer program in full, some of its initiatives appear to incentivise suitable start-ups and SMEs to scale their products in the defence markets. This includes the Accelerating Sovereign Industrial Capabilities Program, which as of June 2024 is providing funding of up to A$12 million “to enable faster commercialisation of larger scale defence R&D activities and collaborations” aligned with sovereign defence industry capabilities.66

Financing

In 2023, Export Finance Australia and Westpac announced a partnership to provide capital solutions and expertise to sovereign defence companies. A USSC report noted this first-of-its-kind initiative has been successful in smoothing capital flow for SMEs and in increasing access to finance to support build components and capital expenditure.67

This was followed by the Australian Government’s commitment to enhance private investment in sovereign defence industry in the 2024 Defence Industry Development Strategy. The strategy previewed action to enhance collaboration between the Defence Department, investment community, and industry, including a “pilot project” to assess investment appetite and opportunity for these stakeholders to invest in sovereign firms producing priority capability.68 The announcement was preceded by the first Treasurer’s Investors Roundtable for defence industry in late 2023.69 This brought together leading investors from Australia’s largest banks, superannuation funds, venture capital funds, and asset managers to discuss investment opportunities in defence industry. It resulted in the solicitation of an expression of interest through AusTender in July 2024 for investor participation in a public-private defence investment fund. This indicates how greater integration of private capital in the Australian defence sector is already underway.70

Acquisition and procurement

In 2020, the Department of Defence launched STaR Shots (Science, Technology and Research Shots) with the release of the Defence Science and Technology Strategy 2030. Initially, this program underpinned the outcomes of the then-Next Generation Technologies Fund (NGTF) but has carried on since the closure of that initiative. Broadly, STaR Shots aims to provide a clear path from R&D to the adoption of technology by the department and the ADF and aims to align R&D efforts to the department’s future force structure priorities.71 The program’s existence demonstrates that defence leaders understand the need to clarify innovation pathways to industry. However, the program itself is not designed to reform the acquisition process but to deliver capability as close to that point as possible. The acquisition process is handled separately through Defence’s Capability, Acquisition, and Sustainment Group. Some analysts have therefore questioned the extent to which STaR Shots can improve innovation outcomes and called for end-to-end capability development reform, which would include coordination with CASG, as suggested in the 2015 First Principles Review.72

The government announced the establishment of the Advanced Strategic Capabilities Accelerator in April 2023. The announcement previewed a “more flexible and agile approach to procurement” and a focus on the translation of innovation to acquisition.

Following this, in 2022, Defence scientists, Navy officials, and Anduril Australia robotics specialists pursued a first-of-its-kind collaboration under a co-funded arrangement to produce 3 autonomous robotic undersea warfare prototypes, known as Ghost Shark.73 The collaboration proved that contracting and development timelines can be significantly shortened from the traditional 12 to 36-month process.74 Although the final product is not set to be delivered until 2025, the project serves as a useful case study in speeding up lengthy acquisition and procurement processes that have traditionally deterred the commercial technology ecosystem from the defence sector.75 USSC analysts have previously identified the willingness of Anduril Australia and the Department of Defence to take on a greater degree of risk “to ensure a flexible contract” as a major success factor in this case study.76 Other reasons for the project’s speed include: the provision of senior-official support; additional financial and resource bandwidth provided by the co-development agreement; the creation of an executive steering group, project management committee, and several working groups to provide ongoing decision-making support; and the existing strength of relationships between senior Defence and Anduril leaders.77 In addition, exogenous global strategic factors including the war in Ukraine reportedly influenced Australian Defence leaders to accelerate attention on autonomous warfighting capability.78

In recognition of Australia’s stagnating defence innovation ecosystem, the 2023 Defence Strategic Review called for the establishment of national science and technology infrastructure that “enables the development of disruptive military capabilities” and achieves scale by leveraging national and international partners, with the United States identified as central to this aim. Indeed, the DSR recommended the Department of Defence pursue more significant “scientific, technological and industrial cooperation in the Alliance.”79 In response to this innovation problem, the government announced the establishment of the Advanced Strategic Capabilities Accelerator in April 2023. The announcement previewed a “more flexible and agile approach to procurement” and a focus on the translation of innovation to acquisition.80 Leading ASCA officials have noted that procurement reform is a critical part of this process.81 Though a young initiative, ASCA has made progress in reforming time to contract. One example of this is the Sovereign Uncrewed Aerial System or UAS Challenge, which achieved the solicitation of contracts within 3 weeks from the point of successful evaluation. Officials noted that lower identified risks associated with this activity enabled the acceleration of typical procurement timelines.82

United States

Improving the market thesis

Established in 1999, In-Q-Tel is the US Government’s not-for-profit venture capital arm and actively works to reduce barriers to working with the federal government for dual-use start-ups in the national security sector. In-Q-Tel does this by improving access to government, championing portfolio companies’ work and providing market information, engineering support and capital solutions to portfolio companies.83 Data from the US Government’s Defence Business Board — a group of senior leaders that provides the Secretary of Defense and Assistant Secretary of Defense with independent advice on defence business management — found that over 70% of the companies In-Q-Tel invests in have never engaged with government before.84 From this perspective, In-Q-Tel has materially increased the volume of non-traditional suppliers in the defence industrial base, both by improving access to the defence market and offering financial support in the form of strategic investments. Over time, In-Q-Tel has had a number of extremely successful investments that have had positive impacts on the trajectory of the national security community and the commercial sector more broadly. Prominent examples include Keyhole Inc. which became Google Earth and in which In-Q-Tel was an early investor, as well as Palantir Technologies, a highly successful non-traditional defence firm that supplies data analytics platforms to both intelligence communities and commercial customers.85

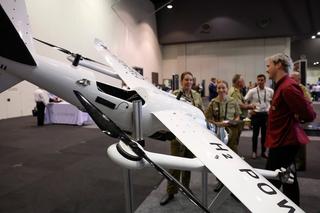

In 2020, DIU launched the Blue sUAS initiative to create a viable alternative to Chinese drones and robust domestic supply chains for their parts. Blue sUAS standardised product requirements for the US Army’s Short-Range Reconnaissance Program of Record, which aimed to support the acquisition of a “rapidly deployable, personal reconnaissance vertical take-off and landing sUAS for the dismounted soldier.”86 In doing so, Blue sUAS’ broader objective was to encourage technology adoption across multiple parts of the military services. The program focused on aligning “requirements, resources, development, testing, and user experimentation across DoD from the start.”87 This alignment improved the defence market thesis for suppliers by increasing the drone market within the US Government. It also enhanced economic security within the defence and broader industrial base, limiting reliance on adversarial firms for drones and their supply chain components.88

In addition to expanding industrial base supply chains for drone technology, the Blue sUAS program has also emphasised developing “friendly-nation industrial base(s) to produce best-in-class capabilities and achieve scale economies for vendors.”89 This is an important detail and points to work that could be done with the AUKUS partners to shore up broader industrial base support for interoperable technology and will be touched on in the recommendations section below. Due to the initial success of Blue sUAS, which has seen participating drone companies sell their products to defence, industry, and to law enforcement, the program has gone through further iterations.90 DIU is currently working on Blue sUAS 2.0, to improve the “diversity, capability, and affordability” of capabilities available to the DoD and other agencies through this program.91

To improve the accessibility of the defence market for non-traditional entities, the DIU has established 3 additional programs to locate and encourage non-traditional talent to work with DoD. The first of these initiatives, the National Security Innovation Network was established in 2016 and supports talent programs in more than 100 universities, resulting in broader and more diverse participation in defence innovation.92 Since its inception, talent scouted by the program has provided solutions to 524 DoD challenges and over 40% of the cohort have entered the national security sector, either in government or the private sector.93 DIU has also expanded their physical presence in recent years, establishing Defence Innovation On-Ramp Hubs in 5 states outside of traditional tech centres to capitalise on expertise in these regions.94 Finally, DIU has sponsored Hacking4Defense, an externally-operated university program that enables students to work on real national security challenges with agency representatives. This program has resulted in the founding of innovative start-ups that have gone on to secure contracts with DIU, including Capella Space.95 These initiatives are exactly the sort of lateral and creative engagement the DoD should be conducting to attract diverse and non-traditional talent to the department, and to the modern national security innovation base more broadly.

These initiatives are exactly the sort of lateral and creative engagement the DoD should be doing to attract diverse and non-traditional talent to the department, and to the modern national security innovation base more broadly.

Financing

In 2002, following a US$25 million allocation in the Defense Appropriations Bill, the US Government established the Army Venture Capital Corporation (AVCC). The AVCC aimed to emulate the success of initiatives like In-Q-Tel and improve financing pathways for non-traditional start-ups developing promising technology that could be adopted for the US Army.96 Unfortunately, the AVCC fell short due to a lack of funding from the US Congress which quickly led to financial and human capital barriers. These issues compounded after the 2008 financial crisis, which saw many of the organisations’ portfolio companies collapse.97

In 2022, the Department of Defense established the Office of Strategic Capital (OSC) to increase private investment in technologies critical to US national security. The OSC works with the Small Business Investment Company Critical Technologies Initiative –a collaboration between the DoD and the Small Business Administration to crowd capital into critical technologies — and matches private capital with federal loans. This collaboration therefore increases demand signals and overall investment in DoD priority technology areas.98 Unfortunately, the OSC’s progress has been bulwarked until recently due to a lack of congressional authorisation to progress loan and other funding support. With congressional approval now secured, the OSC has submitted a US$144 million budget request for FY2025 to support its activities.99

Within the DIU, the National Security Innovation Capital program — authorised by the 2019 National Defense Authorisation Act — identifies start-ups developing dual-use hardware technology of interest to the DoD and supports their growth through capital injections.100 Hardware defence equipment has historically been considered too risky for many venture capitalists because of the capital expenditure involved in scaling this technology.101 In this sense, the program has provided critical support to private sector companies that otherwise may not have been able to scale promising technologies for defence purposes. Since its inception in 2021, the program has awarded prototype development contracts to at least 5 companies.102 The National Security Innovation program uses a legal instrument called Other Transaction Authority (OTA) to speed-up contracting processes in these instances.103

The Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (SBTTR) programs were established in 1982 and 1992 respectively, to fund research and development for small businesses with products that may have utility in military or commercial contexts and have viable pathways for commercialisation. The DoD is one of 5 agencies active in the SBTTR program.104 A 2023 Atlantic Council report argued that the DoD and Congress should broaden the aperture of firms eligible for SBIR grants, noting that at present many promising companies were excluded from consideration because they had more than 50% backing from venture capital or were a small but publicly-traded business.105 This suggests that many firms are slipping through the cracks of the SBIR program, which is a missed opportunity to integrate innovative commercial technology firms into the national security innovation base.

Acquisition and procurement hurdles

The United States has introduced a number of creative instruments to address wicked acquisition and procurement hurdles that have long plagued defence industry and discouraged commercial technology entities from working with defence. OTA’s are one example. This tool has enabled the US Defence of Defense and other US innovation entities to execute quick customisation and acquisition of commercial technology.106 First employed in 1958 by the Eisenhower administration, OTA’s facilitate rapid engagement and acquisition of commercial technology from commercial or non-traditional defence contractors.107 Their utilisation has empowered the DIU to deliver 52 technology solutions to operators on a condensed timeframe as of March 2023.108

The United States has introduced a number of creative instruments to address wicked acquisition and procurement hurdles that have long plagued defence industry and discouraged commercial technology entities from working with defence.

The DIU has also developed a prototyping solution called a Commercial Solutions Opening (CSO), which provides a mechanism for DoD to incentivise non-traditional defence entities to work with government by offering flexible and fast pathways to the award of an OTA.109 Because of early examples of success since first use in 2017, the 2024 National Defense Authorisation Act directed the US secretary of defense to utilise CSO’s 4 times yearly to acquire technology at pace. This change suggests that CSO’s have proven valuable in reducing disincentives for commercial technology companies considering doing business with the DoD.110 As a result, Section 803 of the FY22 National Defense Authorization Act provided the DoD with permanent CSO authority, codified in 10 U.S.C. §3458.111

The DoD has also recently introduced a number of pilot programs to support faster procurement and train contracting officers in commercial procurement practices. In 2022, the DoD announced a pilot program “to Accelerate the Procurement and Fielding of Innovative Technologies (APFIT)” and began to provide procurement funding from US$10-50 million to small and non-traditional firms with mature products ready to be transferred into operation.112 In just 2 years, this has enabled 21 programs to procure novel technology for the US services.113 Moreover, the 2023 introduction of DIU’s Immersive Commercial Acquisition Training Program signalled DoD’s intent to address acquisition and procurement issues from another angle. The program aims to promote the use of “agile acquisition methods” by training DoD acquisition staff on DIU’s acquisition process, which emulates commercial practices.114 Though too early to evaluate this program’s success, efforts to align DoD’s acquisition practices with those of the commercial sector are undoubtedly a positive step. The question is whether acquisition reforms can permeate broader departmental culture, acknowledging the small scope of this program and DIU within the broader Department of Defense.

Collaborative lines of effort

To their credit, Australia and the United States have begun to progress several collaborative initiatives to address market thesis, financing, and acquisition and procurement challenges outlined above. These efforts aim to support non-traditional vendors to engage with the US and Australian DoD’s and are linked to AUKUS Pillar II. Therefore, they are not strictly bilateral initiatives.

Firstly, to improve the accessibility and thesis of the AUKUS Pillar II market to a broader range of stakeholders, the 3 AUKUS governments established an Advanced Capabilities Industry Forum in December 2023. This group aims to support a broad range of industry stakeholders to engage with the objectives of Pillar II, including by holding discussions about “policy, technical and commercial frameworks” for the development of advanced capabilities.115

The AUKUS governments also officially endorsed the AUKUS Defence Investors Network (AUKUS DIN) in December 2023. This is a network of private capital investors from over 300 venture capital firms, family offices and corporate venture capital groups, operated by US-headquartered innovation firm BMNT.116 AUKUS DIN offers a forum for investors to discuss how private capital can complement government investment into Pillar II development and support the scaling of advanced capabilities.117 Although the network is operated by a non-government entity, US Secretary of Defence Lloyd Austin and Australian Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Defence Richard Marles acknowledged the network’s ability to “facilitate targeted industry connectivity” in a December 2023 joint statement with UK Secretary of State for Defense Grant Shapps.118 Unfortunately, the firm’s external positioning limits its ability to coordinate an overarching investment strategy among private investors, including the extent to which capital is deployed in alignment with government objectives.119

Summary

The need to expand the traditional defence industrial base to a broader national security innovation base — encompassing start-ups, SMEs, research communities, and other non-traditional defence suppliers — has scarcely been more urgent. Officials at the highest levels of government in Australia and the United States recognise that to remain technologically competitive they must become easier customers for the commercial technology sector. Notwithstanding this recognition and numerous initiatives designed to alleviate the challenges detailed above, commercial technology entities remain disincentivised from the defence market due to its poor market thesis, financing issues, and complicated acquisition and procurement processes. Together, this collective of wicked problems represents a stark deterrent to innovative contributions to national security in both countries. The following recommendations detail where and how discrete cooperation between Australia and the United States could alleviate these challenges (as well as those relevant to the United Kingdom where relevant to AUKUS Pillar II).

Recommendations

Improving the market thesis

Problem: Start-ups and SMEs in the commercial technology ecosystem in both Australia and the United States are disincentivised from working with defence partly because of the discrepancy in size between the defence and commercial markets. This is exacerbated by the need to adhere to specific requirements for defence equipment, which limits the ability to build economies of scale.

Solution: Australia and the United States should emulate the success of the US’ Blue sUAS program to improve the market thesis of the defence sector for dual-use firms. Bilateralising or even trilateralising this program within the US-Australia or AUKUS Pillar II constructs would involve standardising the requirements of limited technology such as underwater drones.

This would uplift the collective purchasing power of involved governments and subsequently improve suppliers’ ability to produce economies of scale. While this may require parallel and complex conversations about interoperability requirements, an obvious place to start this work would be AUKUS Pillar II, where action to enhance the interoperability and interchangeability of existing advanced capabilities is already underway. One example is the development of trilateral algorithms that enable information sharing from each partner’s Boeing P-8 maritime surveillance aircraft sonobuoys, deployed underwater to hunt submarines.120 Efforts to standardise technology requirements should be led by government rather than industry, to send a strong message about the intent to support and integrate the commercial technology ecosystem into the defence industrial base for specific sets of capabilities. The success of this initiative should be determined by monitoring any resulting uplift in suppliers for approved technologies after a one-year period.

Problem: Contracting opportunities and pathways to scale in the Australian and US defence markets are not well understood nor perceived to be accessible by start-ups and SMEs in the broader commercial technology ecosystem. If this trend continues, the market thesis for the defence sector will remain weak to these stakeholders to the detriment of dual-use innovation initiatives like AUKUS Pillar II. In the AUKUS Advanced Capabilities Industry Forum, the AUKUS governments are already starting to address this by facilitating “policy, technical and commercial frameworks” discussions.121

Solution: To demystify pathways to contracting and scale, Australia and the United States should build on existing efforts in the AUKUS Advanced Capabilities Forum and supplement these with a US-India Defence Acceleration Ecosystem-style industry and academia workshop series.122 Although INDUS-X was only launched in 2023, its industry and academia workshops have already identified multiple barriers to bilateral defence innovation, including a lack of joint “training and exchange programs” to support the commercialisation of research, among others. The workshops have provided a forum to begin discussing solutions with industry and government at pace, such as the modification of policy frameworks and exchange programs to support more effective technology adoption and commercialisation.123 Equivalent workshops could be hosted by US and Australian universities to alleviate the burden from the government and unpack pathways to contracting and scale for innovators in the commercial technology ecosystem who may be unfamiliar with defence contracting processes. Much like the INDUS-X workshops, this series would provide a forum for the two-way exchange of information and learning between industry and government. Communicating the value of attending these workshops to busy commercial technology sector stakeholders may be a challenge. Sustained and improved government-industry-academia engagement across a number of departments will therefore be a key marker of success for this initiative. Likewise, success could be measured by the number of new firms that engage with the US and Australian Departments of Defence as a result of increased outreach activities.

Financing

Problem: Start-ups and SMEs in the broader commercial technology ecosystem in both Australia and the United States require greater financial support on the pathway from research-to-prototype-to government contract and scaling than either government is currently able or willing to provide. Venture capital and other categories of private investment are increasingly eager to plug this gap but have historically been circumspect about the profitability of the defence market. They also remain concerned about the government’s ability to award contracts at the scale required to make an investment in the defence sector worthwhile.124

Solution (part a): In tandem with the United Kingdom, Australia and the United States should establish a multi-sovereign venture capital fund for Pillar II advanced capability development. This will send a stronger demand signal to investors about the investment opportunity in defence and provide a bedrock of capital and associated financial expertise for dual-use start-ups. Such a fund could be modelled off the NATO Innovation Fund, which provides “patient capital and technological diligence and validation” to NATO deep-technology innovators and works in tandem with NATO’s Defence Innovation Accelerator for the North Atlantic (DIANA) to match promising innovators with funding.125

Ensuring this fund is seeded with government money in the first instance will be crucial: government must signal their commitment to Pillar II to ensure private capital follows closely behind.

The AUKUS Pillar II innovation fund should build on existing efforts to harness private capital for Pillar II in the AUKUS investors group, led by the innovation firm BMNT126 and be established with a financial contribution proportionate to the size of each country’s defence spending as a percentage of GDP. It could also be bolstered by capital inputs from trusted VC and other private capital, with success to be determined by the extent to which the fund can ‘crowd-in’ private capital investors. Like the NATO Innovation Fund, this pool of capital should be managed by dual-fluency talent. In other words, professionals with extensive VC and deep-tech experience who will be well-placed to provide technical expertise and due diligence to promising start-ups on their pathway to contracting and scale. Ensuring this fund is seeded with government money in the first instance will be crucial: government must signal their commitment to Pillar II to ensure private capital follows closely behind.127

Barriers to the creation of such a fund have been explored in depth in another publication by this author. In short, these include the immaturity of AUKUS governance structures in contrast to NATO’s, which is an alliance unlike AUKUS. Other barriers may stem from industrial competitiveness or concerns about duplication with existing national initiatives. These factors arguably prevented the United States from participating in the NATO Innovation Fund and highlight the awkward juxtaposition between the Biden administration’s foregrounding of ‘allies and partners’ and ‘Made in America’ policies.128

Solution (part b): Noting the 2024 US National Defense Industrial Strategy’s focus on economic deterrence and keeping ‘adversarial capital’ out of defence industry supply chains, the fund should leverage work already underway in the US DoD’s Trusted Capital Digital Marketplace program to verify a group of trusted capital providers for this fund without links to adversarial nations.129

Acquisition and procurement

Problem: Despite positive reform, staffing challenges within the DIU and ASCA negatively impact the time it takes for innovation proposals to be assessed, which slows capability acquisition timelines.

Solution: To improve the pace at which proposals can be assessed, ASCA and DIU should direct those related to AUKUS Pillar II areas of focus — both solicited and unsolicited — to a common pool, housed under the Pillar II Innovation Working Group. Acquisition and sustainment staff from the Australian Department of Defence’s Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group, the US Department of Defense’s Acquisition and Sustainment Office, and the UK’s Defence Equipment & Support organisation, engaged with Pillar II work could then provide surge capacity to filter through these proposals at pace, based on a common set of requirements. Taking steps to align AUKUS partner acquisition and procurement systems could also support the delivery of one coordinated Pillar II innovation challenge in the future, rather than 3 simultaneously conducted challenges. However, before this recommendation can be implemented, it may be necessary for Australia to address digital platform security.130

Problem: Australia and the United States have identified the need to align their acquisition and procurement models to that of the commercial sector. Emphasising speed is a primary goal in this respect, and while both countries have made significant strides, there is scope to go further — particularly in the case of ASCA, which is a younger organisation than DIU.

Solution: Australia and the United States should share best practices for integrating commercial ways of working into acquisition and procurement processes. In particular, ASCA would benefit from gaining insight into DIU’s Immersive Commercial Acquisition Training Program and the methods employed to incentivise ‘dual fluency’ talent — those with experience in national security but also in the technology sector or the military — into its workforce, noting the benefits this has for innovation outcomes.131 Metrics of success could include achieving a material increase in ‘dual-fluency’ hires within ASCA as a result of this collaboration. Both countries should also strive to match prototype contracting times with those of the commercial sector.