Australia and the United States share so many historical and cultural characteristics, it remains an oddity the two nations rarely interacted before the Second World War.

Australia and the United States are similar in many ways. The two countries span continents – both home to First Nations’ peoples for millennia preceding European settlement – with immense endowments of natural resources to build and sustain prosperity. Both countries inherit their dominant language and political and legal frameworks from England, with commitments to the ‘rule of law’ encouraging private enterprise and the creation of wealth.

The two countries have attracted millions of immigrants, vital to the economic development and social dynamism of each, a constant source of renewal and creativity.

Australia and the United States, it seems, were long primed to be allies and friends. But with the Pacific separating the two, it would take a world war and new technologies of transport and communications to draw Australia and the United States closer. Even this wasn’t automatic. Australia didn’t begin international automated direct telephone dialling until 1976.1 But once brought together, collaborations between the two countries across science, technology and culture have accelerated, delivering immense benefits, deepening ties and instilling an appreciation of what both cultures value and share. Today, there are countless points of connection between the two nations, spanning virtually every realm of economic, scientific, creative or sporting endeavour.

The Alliance between Australia and the United States is bolstered by these networks driven by individuals and families, businesses and institutions.

Of course, history could have played out quite differently. If not for the American colonies declaring their independence from Britain in 1776, the future of the country that would become known as Australia might have been very different. American independence changed much, including the fact Britain could no longer send convicts to its former American colonies. Indeed, the Constitution of the United States was drafted in 1787-88 as the First Fleet was sailing towards Australia’s Botany Bay.

The genesis of the United States in rebellion and revolution – demanding independence from Britain and winning it in a War of Independence – stands in marked contrast to Australia’s Federation in 1901. The Parliament of the United Kingdom passed the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act (1900), creating a ‘Federal Commonwealth under the Crown of the United Kingdom’ with Australia’s Constitution appearing as section nine of the legislation. Australia had the trappings of independence but unlike the United States, it remained culturally, politically and constitutionally tied to the United Kingdom. As detailed in this volume, Australia’s nascent ‘proto-alliance’ with the United States would be overshadowed for decades by Australia’s ties to the ‘mother country.’

These differences in national founding reveal key differences in values, philosophy and culture between Australia and the United States, reinforced and cemented over time as successive generations learn and celebrate their respective nations’ histories. America prizes individual liberty and freedom and will tolerate vast economic and social inequities as their price.

Like the United States, Australia’s genesis stems from migration to new, titanic lands, driven by a frontier spirit. But Australians are generally not prepared to accept inequalities of the scale witnessed in the United States and are more accepting of state power and regulation to achieve equality or promote the ‘common good’ over individual liberties.

Differences notwithstanding, Australian and US cultures grew similarly but in parallel, not integrating in any substantial fashion until after the Second World War. Perhaps this explains the sporting idiosyncrasy of Australia and the United States both developing their own national football codes – Australian rules and American football – separate from the United Kingdom’s soccer.

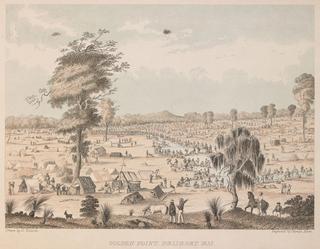

There is little documentation of population flow between the two countries in the 19th century other than movement either way for the gold rushes in California’s Sierra Nevada and northern goldfields from 1848 and subsequent flow to Australia after gold flecks were found in a waterhole near Bathurst in 1851. Australians heard of the promised bounty in California via American newspapers shipped from Hawaii.2 Most Australians who immigrated to the United States settled in and around San Francisco and to a lesser extent Los Angeles, the major ports on America’s Pacific coast.

Exchange was limited as the United States engaged in, and recovered from, its Civil War during the 1860s. English writer Anthony Trollope’s incisive travel writing of the era made a prescient observation about a possible future Australia in his 1873 volume, Australia and New Zealand. Throughout, Trollope cites the United States, a republic, as an example for Australia to follow, despite his pride in his own country’s constitutional monarchy. He understood Australia, as a new nation, would one day desire to seek autonomy from the mother country and seek the prosperity and style of government of the United States.3

The establishment of the Commonwealth of Australia three decades later was not a break from the United Kingdom. Yet the Australian Constitution drew extensively from the US Constitution for many aspects of its creation, including explicit delineation of the powers and functions of the national and state governments and the creation of bicameral national legislature with an ‘upper house’ (Senate) and ‘lower house’ (House of Representatives). Yet the Commonwealth adopted the Westminster model of cabinet government presided over by the Crown’s representative.4

Australia’s grafting of Westminster institutions and conventions onto its federal system – drawing on the American model – is sometimes called a ‘Washminster’ system of government.5 Or, as former Australian politician Sir James Killen remarked in 1988, ‘the waters of the Thames and of the Potomac both flow into Lake Burley Griffin.’6

Studies of the American influence on Australia’s constitutional design suggest it came not from the personal exchange of ideas and experience but primarily through book learning. According to one major account, Professor John Andrew La Nauze’s 1972 work, The Making of the Australian Constitution, the men framing the Constitution relied heavily on Englishman James Bryce’s The American Commonwealth amidst other news, debates and commentary from overseas, including those of a law professor, Woodrow Wilson. Only a few key figures, including Andrew Inglis Clark, Josiah Symon and Henry Parkes had visited the United States and had first-hand experience of American political institutions or culture.7

Incredibly, the first heads of state meeting between the two countries was not until the tail end of the Second World War when Prime Minister John Curtin met with President Roosevelt in 1944.

Cultural interchange was occasional before then. Famously, American writer and satirist Mark Twain toured Australia in 1895, reportedly to save himself from financial ruin with a global speaking tour. He arrived in Sydney’s Watson’s Bay in 1895 aboard the RMS Warrimoo, having followed Robert Louis Stevenson’s directions – sail west and take the first turn left.8

Twain’s barnstorming tour of 15 towns and cities was immensely popular and prompted the later account of his travels, Following The Equator (1897) in which, among many keen observations, he advised it would be ‘unwise’ and unnecessary for the colonies to ‘cut loose from the British Empire.’10 So, pre-Federation an American advised Australia to maintain its links to Empire while an Englishman, Trollope, counselled otherwise!

“If the climates of the world were determined by parallels of latitude, then we could know a place’s climate by its position on the map; and so we should know that the climate of Sydney was the counterpart of the climate of Columbia, S.C., and of Little Rock, Arkansas, since Sydney is about the same distance south of the equator that those other towns are north of it – thirty-four degrees. But no, climate disregards the parallels of latitude. In Arkansas they have a winter; in Sydney they have the name of it, but not the thing itself.”Mark Twain, 1896

Occasional, quirky cultural exchanges marked these years. For instance, on 17 July 1906 American sailors from the visiting American warship USS Baltimore held the first ice hockey game in Australia, against a team of Victorian skaters.

But during the first 40 years of the 20th century, Australia was still tied to British influences. Any cultural exchanges with the United States were more likely one way, with individual Australians heading eastward chasing fame and fortune in the United States rather than Americans seeking it in Australia.

Stephen Loosley AM

Non-Resident Senior Fellow at the United States Studies Centre, Senator for New South Wales (1990-95)

Soft power, despite Joseph Nye’s comprehensive definition, ‘the ability to affect others by attraction and persuasion, rather than the hard power of coercion and payment,’ is not always easy to identify. But it exists and is real, whether in the Australian or American variant.

Examples come readily to mind from Australian experiences in America.

Years ago, I was travelling up the I-5 from Los Angeles to Stanford University in Palo Alto. All was fine until I made a wrong turn just short of my destination and found myself in East Palo Alto. Remembering parental instructions from my childhood, I turned into the nearest police station parking lot. Two cops emerged from the precinct to begin their shift.

Apologising, I went up to them and explained I was an Australian visitor who was lost.

One cop said to me, ‘We’re happy to give you directions, but you will have to answer a couple of questions.’

A little taken aback, I said that was not a problem.

He proceeded to ask, ‘Do Australians really say throw a shrimp on the barbie?’ They were laughing and so was I as I replied, ‘No. We refer to them as prawns. The reference to the shrimp was for American audiences.’

Then the other cop intervened, ‘And do you guys really drink Foster’s beer?’

‘No’ I responded. ‘We make it, but we export it to the US for you guys to drink.’ Both laughed and asked how they could help and upon my query, gave me the directions to Stanford.

That scene of course was the result of the Paul Hogan Australian tourist campaign in which the Australian actor, on the grounds of Kirribilli House on Sydney Harbour, projected an Australian image to Americans and the world. Full marks to Tourism Minister John Brown and to a supportive Prime Minister in Bob Hawke, who understood Hoges’ Australian character was a winner abroad.

A similar experience occurred when I travelled to a visiting US aircraft carrier with the real crocodile hunter, Steve Irwin, among a party of Australians. US sailors mobbed him, and it was all due of course to the success of his show on cable TV in America. The Americans warmed to Irwin’s down-to-earth approach and his obvious physical courage. The same characteristics were present when an injured Steve Irwin went on stage in Los Angeles at a G’Day USA event, complete with Australian fauna, some of which were truly wild.

And that’s the astonishing element in soft power. Regardless of how it is conveyed, and person-to-person contact is best, it establishes trust and a common sense of identity which leads directly to the possibility of the pursuit of common purposes. The hard power of ANZUS is unquestionably embedded in the shared soft power of both Australian and American societies.

Certainly, no better stream for the marshalling of soft power exists than cinema.

The US cinema projects a version of the country which is at once robust yet appealing in the depths of its dimensions. Examples of this reality abound but in politics and government this phenomenon stretches from John Ford’s Young Mr. Lincoln through Mr. Smith Goes to Washington to All the President’s Men. The themes recur. Democratic expressions of will are confronted and potentially thwarted by powerful interests, yet republican virtue prevails. To a world often still in the grip of dictators, this is a powerful message.

Even the most searing of American experiences can be translated to foreign audiences in meaningful and indeed optimistic terms. The Civil War was the bloodiest and most divisive conflict in American history. DW Griffith’s corrupted account of the war and reconstruction in Birth of a Nation has long been eclipsed by more insightful and more honest offerings. The brilliant Spike Lee may still be mesmerised by Griffith’s film, but the celluloid accounts of Black Americans in uniform in defence of the Republic, as evidenced by movies such as Glory, add weight to a gradual rebalancing of the ledger. Steven Spielberg’s magisterial classic, Lincoln, demonstrates the preparedness of American filmmakers to produce a narrative that is at once brutally frank (witness the Congressional passage of the 13th Amendment), yet sensitive to contemporary values.

It is possible to chart the Australian experience in the 20th century through war and peace by absorbing Australian movies from Gallipoli to Between Wars and on to Kokoda. Indigenous life is reflected in films as different as Rabbit-Proof Fence and Sweet Country, with a more nuanced understanding of the tensions between ancient cultures and cascading waves of new arrivals.

Australian soft power is actually most respected for our sports. The Brits in particular acknowledge the contributions made by our athletes at Olympic and Commonwealth levels and our professional sportsmen and women. Sports diplomacy is of particular significance to the Australian step-up in the South Pacific with both codes of rugby prominent in nations ranging from Papua New Guinea to Fiji. Australian team jerseys for both men and women appear to complement the blue jeans of the American Peace Corps.

But few experiences in either the United States or Australia, with the probable exception of religious links, have the impact of education. To glance at the Cabinets of Asian countries is to underline the value of Australian tertiary institutions. This is magnified many times by Australian students studying in the United States. Overwhelmingly, the experience is positive, and the roiling and boisterous democratic experience is absorbed by young people almost by osmosis.

Soft power may indeed be difficult to measure but its qualitative impact upon other nations is a very real factor in foreign policy. Australian and American values often coalesce around common themes. This represents the essential explanation as to why Australians have had such success in Hollywood and why Americans are so comfortable making movies here.

Joseph Nye was right. Persuading people by example is always to be preferred to authoritarian tendencies to intimidate or bully, especially in the form of Beijing’s ‘sharp power’ which often assumes the shape of coercion.

Spirit of competition

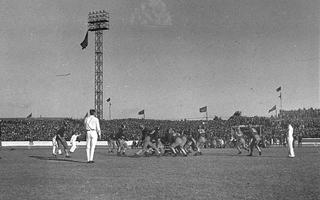

Australia had broader global relationships in sport. Australia’s growing status in the field, including its still-unbroken run of competing in every summer Olympic Games since 1896, resulted in more international challenges and visits. The United States tennis team travelled to Sydney’s Double Bay Grounds in 1909 to challenge Australasia in the Davis Cup final, for instance.

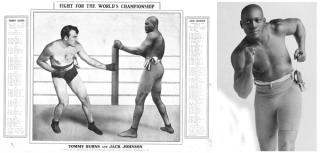

A seminal, and unlikely, contest took place in Sydney on Boxing Day in 1908 when World Heavyweight Boxing Champion Tommy Burns was finally enticed to fight challenger Jack Johnson. The Canadian, Burns, refused Johnson’s challenge for two years due to the verboten rule that heavyweight champions were white and would draw the ‘colour line’ by refusing to fight Black boxers. Australian entrepreneur Hugh ‘Mac’ McIntosh hurriedly built the Sydney Stadium in Rushcutters Bay to stage events during the visit of the Great White Fleet (see chapter 1) and wanted to capitalise on his investment by having the site host a world championship bout.

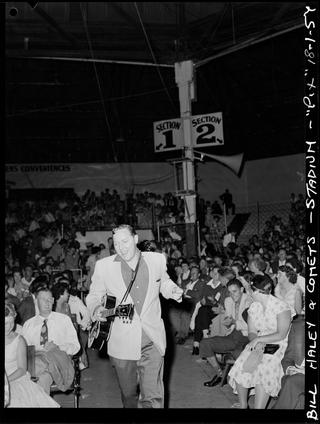

McIntosh agreed to Burns’ seemingly outrageous fee (£6,000) and on the day of the bout 20,000 Sydneysiders witnessed boxing history as Johnson easily outclassed Burns to be crowned the first Black heavyweight world champion.11 The Sydney Stadium would host virtually every major international performer coming to Australia until its demolition in 1970, including many from the United States such as Frank Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald and Bob Dylan. Affectionately known as ‘The Big Tin Shed,’ the primitive venue was described by US comedian Bob Hope as ‘like Texas with a roof on it.’12

Not long after, two Australian legends ventured to the United States for distressing, controversial finales. As a neighbour of Australian actor Jack Thompson warned him before he left to promote the film Petersen there in 1976, ‘Remember Phar Lap and Les Darcy, son!’13

Les Darcy was a wunderkind boxer who turned professional at 15 in 1910 and proceeded to pummel a litany of visiting American boxers as the world middleweight champ. He was encouraged to leave for the United States in 1916 to avoid conscription for the armed services although he controversially said he would enlist after securing his family’s financial security with four fights overseas. In late 1916, Darcy left Australia clandestinely in breach of the War Precautions Act; subsequently, the state of New York refused to sanction his first scheduled bout. Darcy took US citizenship in 1917 but died of pneumonia months later, a folk hero back home.14

Decades later, Phar Lap, the New Zealand-bred thoroughbred racehorse dominated Australian horseracing, beating all comers, winning the Melbourne Cup and two Cox Plates and galvanising a wan nation during the Great Depression. After sailing to the United States, the horse won the most lucrative horse race ever, the Agua Caliente Handicap in Mexico in 1932. But soon after while still in the United States, Phar Lap haemorrhaged and died, leading conspiracists to believe he was poisoned. Research decades later concluded Phar Lap died of acute bacterial gastroenteritis.

Silver screen seduction

Before the First World War, American culture infiltrated the Australian theatre arts to a minor extent but posed no meaningful challenge to the dominance of British customs and influences Australians adopted and adapted. And in some areas, such as speech, writing and humour, Australians forged their own vernacular and style developed in part as a reaction to British mores.

The one field where the United States began to wrest influence and would continue to do so during ‘the American Century,’ was cinema (and later television). A year after Parisians paid to watch the Lumiere brothers’ project their first films in 1895, the Lumieres shipped an early version of their revolutionary product to Melbourne. Australians took to the new visual form enthusiastically, recording a Manly steam ferry in October 1896 and the Melbourne Cup in 1906. That same year, Charles Tait produced The Story of the Kelly Gang, which is regarded as the world’s first full-length feature film. Between 1906-12, Australia led the United States and the United Kingdom in producing feature-length narrative films,15 which were mainly about gold prospecting, convict life and horseracing (bushranger films were banned). At the same time, Los Angeles became a beacon for immigrants after it grew out of the desert at the turn of the 20th century and developed its own film sector. Australians began landing there to try their luck.

While Australians swarmed to Hollywood, the business of Hollywood overwhelmed Australia. A consolidation of exhibitors and distributors before the First World War resulted in an easier means for American distributors to dominate with exclusive deals in the 1920s. The opportunity Australia had to create its own sustainable film industry was trumped by the integration of Hollywood production, marketing and distribution into Australian cinemas. By 1923, 94 per cent of films screened in Australia were American.16 Ever since, American films annually have taken 70-90 per cent of Australia’s annual cinema box office.17 The cultural osmosis from that dominance for a century is extraordinary.

The early lights of Hollywood

Before Nicole Kidman and Hugh Jackman, a steady stream of Australians were lured to the bright lights of Hollywood. Clyde Cook made his name in silent movies as an accomplished vaudevillian while Snub Pollard worked with comic legend Harold Lloyd and Enid Bennett played Maid Marian opposite Douglas Fairbanks in the 1922 hit Robin Hood. Australian Louise Lovely was an inspiration for many Australians after signing a contract with Universal Studios (after an executive suggested changing her surname from ‘Carbasse’ because she was ‘lovely’). And champion swimmer Annette Kellerman’s career bloomed when she was the first major actress to appear naked on screen, in the 1916 film, A Daughter of the Gods, which reportedly was also the first million-dollar film production.

Directors and crew also succeeded in Hollywood. Rupert Julian directed the 1925 version of The Phantom of the Opera and Sydney’s John Farrow (Mia’s father) had an extensive career as screenwriter and director across four decades, including winning an Academy Award in 1956 for the screenplay of Around the World in 80 Days. Kiama’s Orry-Kelly (Orry George Kelly) became a sought-after costume designer during Hollywood’s golden 1930s and 40s and was Australia’s first triple Academy Award-winner for his costume design on An American in Paris, Les Girls and Some Like It Hot.

The Second World War further entrenched US cinematic power and nobbled Australia’s, although it provided Australia’s first Academy Award-winner, Damien Parer, who won the documentary award in 1943 for his film shot in New Guinea during the war, Kokoda Front Line.

It would be the first of what is now a flood of Academy Awards and nominations for Australians representing the fluid cultural transfer between the two nations. By 2021, Australians had won 44 Oscars and more than 160 nominations, more than any nation other than the United Kingdom and, obviously, the United States.18

The introduction of television to Australia in 1956, coinciding with Australia hosting the 1956 Olympic Games in Melbourne, ushered another sharp cultural shock after the Second World War. For the first time since European colonisation, Australia’s cultural cues came more from the United States than the United Kingdom, as the United States entered homes across the country through television. Hollywood’s post-war influence and economic power grew and affected Australia tangibly as its own film sector shrank, hurt by an inability to secure financing, exhibition and distribution for domestic films.

The anticipation that the new medium of television might be a boon for local production and representation was quelled when the ready pool of American programming, and British and Hollywood films filled Australian TV schedules. The first two decades of Australian commercial television were dominated by American comedy and drama (in 1959, the 10 most popular programs on Australian television were American19).

Meanwhile, the national broadcaster, the ABC, modelled itself on the UK public broadcaster, the BBC, and consequently programmed predominantly British content. Between 1956 and 1963, almost all content screened on Australian television was sourced from overseas and Australian programming tended to be based on formulae set by American programs (Reg Grundy famously made his fortune repackaging American game show formats such as Wheel of Fortune for his home market).20

To be sure, the United States emerged from the war as the dominant global economic power and was well-placed to export its cultural product to the world and, as Australian affluence grew, Australians were primed to consume that product. Additionally, during the following decades, much American television content more suitably reflected Australia’s way of life, the sunny optimism of shows like Bewitched, The Beverley Hillbillies and The Brady Bunch were more aspirational than the class-based struggles of the United Kingdom’s On the Buses, Steptoe and Son and Are You Being Served?

Australian television developed its own identity throughout the 1960s and 1970s before a respite from American cultural dominance when the successive Australian governments of John Gorton and Gough Whitlam invested in a domestic film industry in 1969 with funding for an experimental film fund, national film school and publicly-funded development body. The 1970s was Australia’s own ‘new wave’ producing distinctly Australian films locals flocked to, such as Alvin Purple and Stork, art films attracting global attention including The Getting Of Wisdom, My Brilliant Career and The Last Wave, and artists who would soon become established and feted figures in Hollywood, including directors Peter Weir, Gillian Armstrong, Bruce Beresford and Dr George Miller, and actors Mel Gibson, Judy Davis and Jack Thompson.

The Honourable Joe Hockey

Australia Ambassador to the United States (2016-20)

The period from 2016 until 2020 – my term as Australia’s Ambassador to the United States – will undoubtedly be remembered as one of the most chaotic and charged in the nation’s recent history. For many long-standing allies, the arrival of the Trump administration resulted in new and unpredictable pressure points: traditional diplomacy was shown the door. Many countries were left scrambling to prosecute their agendas with Washington in the four years that followed.

Australia’s relationship with the Trump administration did not get off to a great start. The well-accounted telephone call between President Donald Trump and Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull about the Obama-era deal to send refugees held on Manus Island and Nauru to the United States put us on the back foot. This was undoubtedly a low point of my term. I had been optimistic about that call beforehand because Prime Minister Turnbull had previously had a good conversation with President-elect Trump back in November. Instead, the January 28 call went off the rails after just 25 minutes instead of the scheduled hour. A transcript made its way to the media not long after.

Following the call and subsequent leak, we weren’t just worried about the refugee deal but the whole trajectory of US-Australia relations. Yet I believe deeply in the enduring strength of the American-Australian relationship, founded on our shared history and common values. And it was this special connection, which I refer to as our ‘Mateship,’ that we relied on during that period to differentiate Australia and help prosecute our interests with our most important strategic partner.

The secret to any campaign is to have a story to tell – a narrative that can capture the attention and imagination of your audience. Australia’s relationship with the United States operates at many levels, and during that most unconventional of administrations, it was more important than ever to clearly define what sets our relationship apart. Not just to the White House but across Congress, at the state-level where more decision-making was devolved, and within the business community.

So we launched the ‘100 Years of Mateship’ campaign. We needed Americans to remember how Australia has always supported the United States, whether it was through the use of Australian facilities in the Apollo 11 Moon landing, our joint military efforts in Vietnam, Korea, Afghanistan and Iraq, or the fact that Australia is the United States’ largest research partner. The Mateship campaign reminded America of our shared history, helped re-introduce Australia to a new generation of Americans, and raised Australia’s status with American decision-makers.

After that testy phone call, we worked hard to build a broad, bipartisan coalition of support for Australia by relaunching the Congressional Friends of Australia Caucus and deploying a US-wide soft diplomacy campaign. We also worked hard to improve relations between Trump and Turnbull, culminating in a face-to-face meeting on the 75th anniversary of the Battle of the Coral Sea in May 2017, on board the USS Intrepid in New York City.

I spoke with the prime minister and Reince Priebus, Trump’s chief of staff, to set up the USS Intrepid event. Onboard the aircraft carrier, the two leaders reconciled and cleared the way for us to shift the narrative to celebrating our first 100 years of mateship and look ahead to the next.

While the Trump administration slapped tariffs on products from major allies like Canada and the United Kingdom, Australia was spared. Australia also dodged Trump’s caustic rhetoric as he called Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau ‘weak’ and ‘dishonest.’

Trump even postponed a meeting with the Danish Prime Minister over the aborted Greenland purchase effort. Meanwhile, for the remainder of Trump’s time in office, we deftly delivered on Australia’s national interests without experiencing the same blowback as other allies and partners.

I learned a lot about Australia’s relationship with America and Americans during my time as ambassador. Perhaps most importantly, I realised our mutual values and shared history are stronger than the men and women who, from time to time, might lead these nations. Australians and Americans have fought side-by-side in every major conflict since the Battle of Hamel on the fourth of July 1918, America’s Independence Day. The story of our shared history resonates because of the depth of both the human and business connections that have grown since that day on the battlefields in France.

Australia and America will face more challenges together. For the foreseeable future, our shared challenge is the rising People’s Republic of China. As China uses tools such as economic coercion and espionage against Australia ever more frequently, it is vital the United States and Australia not only remember our shared history but continue to deepen our partnership. On this 70th anniversary of the signing of the ANZUS Treaty, I confidently keep my faith in US-Australia mateship as our countries look at the world to come.

Culture as currency

Australia’s cultural aspirations before the Second World War weren’t dominated by the British though. Australia saw an affinity with the United States, even seeing it as an aspiration. Some Australian leaders saw it as a model for the smaller nation, most particularly Australian Prime Minister William Hughes, who in a 1918 statement to Washington proclaimed ‘What we are, you were; and what you are, we hope to be.’21

Between the First and Second World Wars, there was criticism of American cultural influence in Australia, mainly based upon the lesser morals of American comics, magazines and films (e.g., Damon Runyon, Edgar Rice Burroughs, the Marx Brothers and The Three Stooges), and cheapness relative to the established supposed ‘high culture’ and majesty of the British literary and theatrical canon (e.g., William Shakespeare, the Brontës, Gilbert and Sullivan and Charles Dickens).

The mass of American troops arriving in Australia during the Second World War was a watershed. It was the most sustained contact Australians had with another culture since the gold rushes of the 19th century, which brought a range of new cultures, including Chinese. The hundreds of thousands of American troops on the Australian mainland from 1941 until the end of the war created ‘Americamania.’22 The glamour and culture previously only seen on the big screen arrived, bringing with it American products and tastes, money and goodwill. Australian businesses rushed to supply them and the Americans introduced their desires and mores to Australians, including music and dance.

The influx of Americans during the war boosted Australian sport, with contests between Australian and US army personnel in athletics, baseball and other sports. It also presaged a peak in immigration to the United States, due to booming US economic activity – and the exodus of up to 15,000 Australian war brides who married US servicemen.23 This didn’t please Australia’s men, many who were engaged in battle overseas; they shared with the British the derogatory phrase of American servicemen as ‘overpaid, over-sexed and over here.’24

Conversely, Americans still stuggled with Australian culture. Thompson’s film Petersen used redubbed Australian voices for its American release in 1975 and the initial Mad Max film had an American voice track in 1977 (the fourth film in the series, Mad Max: Fury Road would win six Academy Awards in 2016).

That changed in the 1980s when a former Sydney Harbour Bridge rigger turned comedian, Paul Hogan, led an Australian tourism campaign in the United States. Australian Tourism Minister John Brown asked Hogan if he could sell his own country to the United States as well as he was then selling beer (Foster’s Lager) to the United Kingdom. Hogan’s tourism campaign gave Australia the identity of a welcoming place to Americans at a time when Australia barely had a global identity.

‘What he did by improving our image, or giving us an image – we basically didn’t have one before that, we were seen as a zoo, you know, interesting marsupials and no people – and giving the world that view of Australia as a welcoming happy place and the Australian individuals as being laid back, irreverent and very happy – you couldn’t estimate what that meant,’ Brown said.

‘It took us from 1788 to 1983, which is 195 years, to get to 800,000 visitors a year. We put Hogan on TV in America and in the next five years we went from 800,000 to 2.4 million. And that was the basis of the tourism industry, the modern tourism industry, in Australia and the progenitor for the hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of infrastructure that’s been built since that makes us the most desirable tourism place in the world.’25

Hogan parlayed that success into a romantic comedy film, Crocodile Dundee, that opened on 879 screens in the United States in September 1986 – defiantly without dubbed voices despite his American distributor’s suggestion – and became the biggest grossing film in Australia’s history, only pipped by Top Gun as the most successful film of 1986.

Paul Hogan AM

Writer, producer and star of Crocodile Dundee (1986), Crocodile Dundee II (1988), Crocodile Dundee in Los Angeles (2001) and Charlie & Boots (2009)

I was probably always a better salesman than a comedian or actor. With the advertising I did, I was real, and it was real. That’s why the ads were successful. I believed in the things I sold.

When I was in the United Kingdom and having a great time doing some Foster’s ads, John Brown, the newly appointed Australian Minister for Tourism sought me out. He was part of the new Labor government under Bob Hawke elected in 1983 and they were out to shake things up, including building a tourism sector.

Brown said ‘You’re going well over here, Hoges, selling beer to the Poms. Do you think you could sell Australia to the Yanks?’

‘I’ll certainly have a crack,’ I replied. So I went to the States to check out the target. I like the Yanks and while it’s a very similar culture to ours, I was quickly reminded there were a few accent and language differences, particularly in the early 1980s.

I found out Americans are really into their politics and social issues. They’re very passionate, whereas we Australians are the exact opposite, apathetic. We’re among the small number of countries in the world where they’ve got to force us to vote, or we wouldn’t bother. So, there’s a clash there. The Yanks are sort of famous for their passion and we’re sort of famous for our apathy.

And we found that almost every country in the world was advertising its wares in the States. So we decided, instead, to advertise our people. We’d say, ‘The best thing about Australia is Australians. We’re friendly, perfect hosts. You’ll have a good time, and we’ll be glad to see you.’

People sometimes ask me what it takes to be an Aussie, and I say it’s simple, ‘Just wanting to be one.’ So it wasn’t a big stretch for me, John and the boys from ad agency Mojo to come up with a tourism campaign that was fun but also authentic.

Our ‘America, You Need A Holiday’ ads aired in the States from January 1984. The ads said, in effect: ‘Come over to our place.’ And Americans did. Australia went from the 28th-most desired destination to number one in a few months. Tourism would eventually become our biggest industry, employing now, I’m told, 3.5 million people.

The ads went on to become the most successful tourism campaign ever in America. Actually, the ‘Shrimp on the Barbie’ ad is in the Smithsonian!

Then I was in New York doing a bit of tourist promotion in early 1984 and after leaving a bar, I couldn’t get a cab. It was five o’clock and I’d have to walk. It seemed like everyone in New York was going one way and I was going the other. I remember thinking I’ve spent my whole life in big cities but going against this peak-hour Manhattan crowd makes me feel like a hillbilly. The energy of the city and the people and their fashion and fast-talking was simply overwhelming.

So, as is my way, I started to write a sketch in my head. And the sketch grew longer and I thought I should make it about a bloke from one of the remotest parts of the outback who’d never been to a big city. There were plenty of things to send up but Michael J ‘Crocodile’ Dundee was a completely made-up character.

Crocodile Dundee had a virtually unknown cast and was the sort of movie Yanks would normally treat as a low-budget foreign film filled with wacky accents. But on opening night in Los Angeles, the ever-increasing queue at a cinema in Westwood told us something was working. It opened on the top of the charts and just kept going and going, taking around US$170 million in the United States alone. And this was in the 1980s!

Mick was a good role model, I believed. It was very important he didn’t rely on violence and didn’t kill anybody. Yet he wasn’t a wimp or a sissy. He slayed them with humour.

What none of us understood at the time was Dundee would be the first exposure many people around the world would have to Australian culture. Most people didn’t know anything about us and now people believed he was typical of our culture.

A lot of people, particularly sophisticated international Australian travellers, were not happy about this. But they’ve been happy to claim it ever since!

The ads inviting Americans to share a ‘shrimp on the barbie’ and the character of Crocodile Dundee and his humorous amblings shaped the American view of Australia and remains pertinent to this day. Incredibly, the fish-out-of-water Dundee presents a stereotype of the laidback, light-hearted and adaptable Australian that has taken hold in the United States and encouraged American-Australian collaboration across so many cultural and creative fields. Director Phil Noyce noted Australians have flourished in the United States because they are westernised and adaptable and don’t have a distinct culture.

‘We share the English language and we are brought up on American TV and movies but at the same time you have a different vision of the world, which comes from being Australian,’ he said. ‘You’ll always see a situation differently. That uniqueness of vision is an advantage because that’s what everyone’s looking for in cinema, a new way of looking at something.’26

The easy transfer of Australian talent to the US cultural industries has been extraordinary, outperforming any other nation, even with Hollywood’s penchant for cherry-picking the best global talent. Talents including Nicole Kidman, Hugh Jackman, Guy Pearce, Margot Robbie, the Hemsworth brothers and Naomi Watts are household names while a new generation of diverse Australians including Chris Pang, Remy Hii, Jordan Rodrigues, Geraldine Viswanathan, Natasha Liu Bordizzo and Evan Evagora are now bolstering the ‘Aussiewood’ connections.

Similarly, the modern cross-Pacific ease has allowed Australian music artists including Sia, Flume and Tones and I to succeed in US markets with greater ease than their predecessors AC/DC, Helen Reddy, Savage Garden, Crowded House, INXS and Men at Work.

While cultural clout was building, this did not translate into power to effect change in the United States. When Australian Ambassador to the United States Michael Thawley arrived in Washington DC in 2000, one of his first observations was, ‘Australia was lacking political constituency in the US.’

Strikingly, he recounts, ‘When I arrived, the CEOs of Ford, News Corp, Westfield, Philip Morris, Visy, the head of the World Bank were all Australians – and not that long ago, the CEO of Kellogg’s, J&J and very senior people in IBM. So we had a presence, which I think would have surprised most Australians.’27

But this corporate clout was not reflected in Australia’s reach in Washington, a challenge the new ambassador viewed as an opportunity to create a ‘political constituency.’ His motivation was clear, ‘At the end of the day you don’t get anything in a democratic country without really strong political support.’ His success in winning hearts and minds in Washington DC was evident when Australians secured the sought-after E3 visa, which no other country in the world currently enjoys.

People-to-people ties

A side-deal Australian Ambassador to the United States Michael Thawley negotiated while finalising the Australia-United States Free Trade Agreement (AUSFTA) still generates benefits today. The E-3 Specialty Occupation Workers visa applies only to nationals of Australia and is available to those with a job offer and requisite qualifications. It is popular with young Australians, giving them an advantage over job applicants from every other country in knowing they can guarantee quick entry to the United States.

Another former ambassador, Joe Hockey, said the unique E-3 visa only existed because Thawley, ‘doesn’t listen to what he’s asked to do and does what he wants to do.’

This visa was partially in response to a deep-felt need Thawley discovered when he commenced as ambassador. ‘I felt when I arrived that Australia was lacking a constituency in the US,’ he said. ‘I was very struck, as others have been, [by] the amount of Australian investment in the US and also the presence of Australians in US business.’

Wanting to see more Australians thrive in an economy he admired, he secured the special legislation for a visa other countries envy. ‘For someone who wants to match themselves and gain experience in the most competitive economy in the world with some of the most brilliant people and most fast-growing businesses, there couldn’t be a better opportunity,’ Thawley explained.

Around the same time as the AUSFTA, Australia’s Consul General in Los Angeles, John Olsen, had his own concern that Australia’s innovations and achievements, cultural and commercial, weren’t recognised in the United States as they ought to be. ‘I was struck by the fact they didn’t understand Australia was a modern sophisticated country that was a leader in the Asia-Pacific region,’ he recalled later. He was frustrated by the lack of recognition for the Holden Monaro car, which was being sold in the United States as an American Pontiac GTO, not Australian, despite being designed and engineered in Melbourne and manufactured in Adelaide.

Olsen was tipped over the edge at an Australia Day celebration in the United States that was sponsored by New Zealand entities, where they sang the New Zealand national anthem.28 He assembled a committee to better market Australia to the mass market of the United States and first spoke to News Limited founder, Rupert Murdoch, who supported the endeavour. ‘G’day LA’ would grow to become ‘G’Day USA,’ with Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, the American Australian Association, the Australian Trade and Investment Commission, Qantas and Tourism Australia as key founding partners.29 ‘G’Day USA’ is now the centrepiece of Australian public diplomacy in the United States, a high-profile program of events and dialogues fostering connections between the two countries.

Professor Brian Schmidt AC

Vice-Chancellor of the Australian National University (2016-), Nobel Prize in Physics (2011)

As we celebrate the 70th anniversary of the ANZUS Alliance, the Australian National University is celebrating its 75th anniversary.

Like the ANZUS Treaty, the Australian National University (ANU) was created in the post-war years as part of a deliberate process of nation-building – setting Australia up for peace and prosperity in the decades that followed.

During the entire period stretching from the end of the Second World War until the present day, the United States has been our most important partner for collaborative research, science and technology. My own Nobel Prize-winning research, while involving people working on five continents, was started just as I was emigrating from the United States to Australia but had more than half the team from the United States. But this is just the tip of the iceberg. For example, over the last five years, the ANU has averaged more than 16,000 publications co-authored by Australian and American researchers each year, more than with any other country.

Our research collaboration has led to huge benefits for both countries, connecting us to world-leading knowledge, strengthening people-to-people links and opening up new opportunities for Australian technologies in the United States, and US technology in Australia.

As we look ahead to the next 70 years of Australia-US collaboration, we must acknowledge that the world of science and technology has undergone significant change. Even in the last 20 years, total global investment in research and development has tripled, with more countries now participating in global flows of knowledge, people and technologies.

This creates new opportunities for Australia as well as new challenges. Now is the time to build upon our long history of high-quality collaboration with the United States and work together to build the next generation of connections and technologies that will shape the decades ahead. There are big opportunities to create more opportunities for strategic collaboration between the two countries in key areas such as space, low emissions energy and critical emerging technology areas including quantum science and artificial intelligence (AI).

To give one example: working with the Australian Government and the US Government, leading ANU researchers have been selected to join the Global Partnership on AI to help design the future of responsible AI, data governance, commercialisation and innovation. This is a worldwide challenge, and our trusted relationship enables us to make progress across these hard problems, using the distinct insights that reflect the different cultures, economies, outlooks and geographic locations of our two countries.

We know that the future of science and technology will increasingly be driven by countries in the Asia-Pacific, putting Australia in a unique position. We also know that science and technology alone will not be sufficient to address the big global challenges facing nations. We need a deep understanding of policies, laws, cultures and ethics to steer future innovation in ways that will benefit the greatest number of people. This is where Australia can make a unique contribution to the future of international science and technology, and work with the United States to better understand and harness the capacity of the Asia-Pacific region.

As similar-minded democracies, strategically combining our knowledge and technological resources means the United States and Australia can achieve much more than acting individually, and in the process help support a world order where personal freedom and prosperity can continue to thrive together.

Innovation takes off

In the relationship between the two countries, earned trust and respect has been at the core of their shared successes. Much of this has come through education partnerships. The first treaty between Australia and the United States predates ANZUS by two years, the Fulbright Program.

The Fulbright Program was signed in Canberra on 26 November 1949 by the US Ambassador to Australia, Pete Jarman, and the Australian Minister for External Affairs, Dr HV Evatt, It is the foremost foreign exchange scholarship program of the United States, increasing research collaboration, cultural understanding and the exchange of ideas. It was initially funded by credits from the sale of surplus US war materials to financially support academic exchanges between host countries and the United States. More than 5,000 Australians and Americans have received Fulbright scholarships.

It remains one source of educational and research exchange between the Alliance partners, expanding by the year. Australian research and academic connections with the United States run deep. It is significant Australia’s recent Nobel laureates have won for work conducted in, or in collaboration with, US universities. This includes 2009 winner in Physiology or Medicine Elizabeth Blackburn (Yale) and American-Australian Brian Schmidt, who jointly won the 2011 Nobel Prize in Physics for his work at Harvard before a long research career at the Australian National University.

Extensive collaborations between the two nations in medical research mean the United States is Australia’s top international collaborator in cancer research and Australia is the United States’ second-largest international collaborator in cancer research.30 In 2014, Australia’s Monash University became the first academic institution outside the United States to join Pfizer’s network of research partners in the Center of Therapeutic Innovation network.31 Today, Australian and US universities share more than 1,250 agreements and the United States is Australia’s largest research collaborator.

Australia’s novel perspective powers innovative collaborations with, or in competition against, the United States. A seminal innovation drove Australia’s unlikely 1983 win of the America’s Cup when Australia II became the first non-American yacht to win the prestigious sailing trophy in 132 years. The mysterious winged keel design, only unveiled after the victory, raised Australia’s image in the United States, particularly as Americans sided with Australia against the stuffy and complaining New York Yacht Club. Ben Lexcen’s revolutionary design, which informed future improvements in sailing, also reminded the United States of Australia’s engineering creativity and technical proficiency.

If necessity is the mother of invention, Australia’s harsh climate and antipodean location may play an outsized role in its success. Many Australian innovations – such as the world’s first practical ice-making machine and refrigerator (1856), electric drill (1889) and utility car (1934) – have been the result of individual pluck or adaptability. Yet there is little doubt no single country since the Second World War has helped Australia to be more pioneering than the United States. Beyond now receiving more investment from the United States than any other country, US investment is larger than any other foreign country’s investments in 14 out of 19 sectors of Australia’s economy.32

The economic link between the two countries was encouraged immeasurably by the Lend-Lease Act signed into law in March 1941, in which the United States didn’t just sell US supplies to Allies during the war but also allowed it to lend or lease supplies to ‘the government of any country whose defense the President deems vital to the defense of the United States.’33

In essence, the Lend-Lease Act pump-primed the Australian economy as it grew to meet the needs of the US war machine in the Pacific. It upgraded Australia’s manufacturing capability for aircraft, radios, steel, ships, clothing and tinned foods by providing the latest US plant and equipment and then leaving it behind after Australia cut a deal to pay for the equipment. It left Australia with a much larger and more sophisticated manufacturing base than it had before the war, while also deepened links between the two nations.34

These links expanded in the decades after the war, encouraged by an Alliance that, as Prime Minister Keating said, ‘offers us access to technology, intelligence and training which we could neither afford nor develop on our own.’35

The AUSFTA, negotiated in the first years of the 21st century (see the previous chapter), established an environment from which the Alliance has thrived in science, technology and innovation, as intended.

Robert Zoellick, the US Trade Representative in the early 2000s when he led negotiations, said the rationale for the agreement went beyond trade barriers. ‘We hoped that the FTA would assist Australian business to integrate with US counterparts so Australians would gain from global innovation.’

He contends those involved in establishing the agreement sought ‘to encourage Australian companies to connect with the US-led network for technologies, data mining, specialised customer service, product development, and marketing’ because ‘Australia’s best would benchmark against the top global competitors.’36

The negotiations tested links though. The cultural aspect of the FTA negotiations remained a bone of contention, with Australia’s artistic community protesting vociferously against intellectual property rights. Zoellick noted of the deliberations, ‘We had the cultural issue, where I really had to grind my teeth because it looked to me like Australian actors dominate Hollywood and now (you’re) all over our channels, so we gave in on that one too just to help with the politics.’37

Ultimately, it was deemed to be in the US national interest for the nation’s closest allies, who shared similar values, political systems and cultures, to be both economically linked and innovative.

Oddly, since 1982, Melbourne has produced more number one NBA draft picks than any other city in the world. The Philadelphia 76ers selected Ben Simmons in 2015, Kyrie Irving, who was born in Melbourne but left with his expat family when he was two, was selected by the Cleveland Cavaliers in 2011 and Andrew Bogut was the top pick in 2005. Chicago is the birthplace of five number ones overall but only two since 1982, and New York produced four top draft picks in the 20 years after the year the NBA turned professional, 1949.

The period leading up to AUSFTA saw marked technological innovations, but the true size and scope of their impact was not yet understood. CSIRO’s scientists developed the wireless LAN in the 1990s, with the first demonstrated example in 2000. However, they were not successful in persuading Big Tech to pay royalties for their patented design, forcing a legal struggle where ‘David’ ended up successfully settling with Apple, Microsoft, Dell and 10 more companies.38

As this innovation tension unfolded, in 2004 Google adopted a more collaborative approach with Sydney-based Where 2 to acquire the technology that would become the now ubiquitous Google Maps.39 It was Google’s second acquisition, but the widespread appeal was obvious from the start.

The fluid transfer of people and ideas in the tech space has brought the two cultures closer so, today, an Australian tech platform like Canva has ready access to Silicon Valley venture capital funding and a software company like Atlassian lists publicly on the US Nasdaq rather than its domestic bourse.

Similarly, US professional sports are accessible for the best Australians, who are regularly recruited to the National Basketball Association (NBA) and Women’s NBA and rising in numbers in Major League Baseball.

And with people awake while the United States is asleep, many US companies are expanding bases in Australia to provide 24/7 global service. After Rupert Murdoch’s News Limited exported Australians to aid the establishment of his FOX television networks, now media companies including the New York Times and Washington Post have Australian offices to ensure constant news delivery.

The same competitive spirit that drives both countries on the sporting field also drives their best moments in cultural and technological innovation. Intrinsic to this success is a shared willingness to roll up their sleeves and adopt a new approach, which now spurs them to be able to address challenges that haven’t even been invented yet. The sense of camaraderie and cultural affinity keeps the Alliance going the distance.

Daniel Petre AO

Co-founder and Chair of AirTree Ventures (2014-), Managing Director of Microsoft Australia (1988-91)

One key area where America as a country provides both a global example of best practice and global reach – in a positive way – is innovation, specifically technological innovation.

For decades the significant majority of all major technological and medical innovations have come from America. It has a deep culture of research and development (R&D) and a funding system that allows for and ensures great ideas see the light.

Of course, many countries have been, and continue to be, sources of innovation. Australia has, on balance, punched above its weight in the areas of R&D as applied to medicine and mining innovation. However, it is hard to look beyond the massive innovation ecosystem that is America.

In 2020, approximately US$135 billion was invested by venture capital firms in start-ups across the technological spectrum in the United States. In Asia, the number was US$80 billion and Europe US$33 billion. Yet 2020 was not an anomaly – it is just the most recent example of the culture of innovation – at scale – that exists in America.

For decades, countries around the world have benefited from this focus on innovation. From the obvious – medical technology innovations that have brought new drugs and therapeutic innovation to all parts of the world through to perhaps the less obvious – platforms such as eBay and Google that have allowed hundreds of thousands of small businesses to thrive globally.

Australia and the United States have had a close relationship when it comes to innovation. For decades many of our best and brightest have gone to undertake post-doctoral studies and internships in leading American hospitals, universities and commercial organisations.

Over more recent times, American venture capital firms and corporate entities have looked to invest many billions of dollars in Australian companies – both large and small. The investment in Atlassian nearly 20 years ago and more recently Canva, Octopus Deploy, A Cloud Guru, Safety Culture and Culture Amp have added more support to the global footprint companies like ResMed, Cochlear and CSL had created before them.

Put simply, the powerhouse of investment – America – has worked out that Australia produces great companies. The close relationship between our countries makes investing in us a simple concept to be comfortable with.

Also due to our close relationship, many large American technology companies are now establishing critical mass software development groups in Australia – thus bringing even more world-class skills to our growing technology ecosystem.

So while America is in many ways a country that has many significant issues to resolve, it remains true that in terms of innovation and technological innovation specifically, America is providing value to the world and Australia.