The term ‘Asia-Pacific’ was supplanted by ‘Indo-Pacific’ during the 21st century as attention moved to the region. China’s emergence as a global powerhouse and the booming growth, population and economic sophistication across India, Indonesia, Vietnam, South Korea and other nations in Southeast Asia offered the Alliance opportunities and challenges.

After decades of isolation and domestic orientations, the Indo-Pacific now enjoys unprecedented economic ties. The region is largely inter-connected and outward-looking and represents the world’s biggest trade markets. More than 50 per cent of global GDP is now shared by the six biggest economies in the Indo-Pacific. In 2020, the United States, China and Japan were the top three economies (by GDP) in the world with India sixth, the Republic of Korea tenth and Australia eleventh.1

As a term of geography, the ‘Indo-Pacific’ region refers to the confluence of the Pacific and Indian Oceans, interconnected by Southeast Asia. The emergence and use of the term reflects the strategic significance of the region, although another prompt could be China’s increased political assertiveness and resulting anxiety among its neighbours. In 2006, for instance, India and Japan began sharing strategic assessments for the first time.2 China’s geography, its Belt and Road Initiative of infrastructure investment and its ambition to tap the natural resources of West Asia and Africa elevate the importance of the Indian Ocean as a counter balance.

The shift in global economic and political weight to the Indo-Pacific gave new impetus to US engagement in a region that has always been central to Australia’s interests. The Alliance is well-positioned to maintain a meaningful presence in the dynamic, and occasionally volatile, Indo-Pacific region throughout this century. It took much work to be in a position where a multilateral leadership dialogue such as ‘the Quad,’ or Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, between Australia, India, Japan and the United States could become a logical extension of the aspirations of four major nations.

Both the United States and Australia have contended with challenges in their Asian engagement. Both countries have enduring security and economic interests in the region but, by dint of history and identity, neither is fully ‘of’ the region, resulting in an uneven attentiveness to relationships throughout the region during the 20th century. In the 1990s, Prime Minister Paul Keating actively pushed for greater Australian engagement with the Asia-Pacific region; indeed, his only political memoir is titled, Engagement: Australia Faces the Asia Pacific. Keating sought security in Asia, not from it. Integrating the Alliance into Australia’s Asian future was a central element of Keating’s vision.3

Simultaneously, the Clinton administration built upon its growing interest after the Cold War in a ‘third agenda,’ that is, matters beyond security or trade, such as health, the environment, and an external focus. But it wasn’t yet ready to jump fully into Asia, as National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft told Keating at Kirribilli House on New Year’s Day in 1992, ‘You are anticipating, Prime Minister, a modus operandi for the United States in Asia that we have not yet articulated for ourselves.’4

Keating was fond of saying the United States was ‘the biggest dog on the block’ and thereby a necessary player in the region.5 Keating also conceded ANZUS might be weaker than NATO but it remained ‘a vital insurance policy for us, complicating the assessment of any potential enemy that may come along.’6

‘At the end of the day, ANZUS’ main, and critical benefit may simply be this: it provides standing for us to have our voice heard in Washington, especially about developments in this part of the world,’ he said.7 If, as Keating desired, Australia was to entrench itself in the future economic dominance of the Indo-Pacific while enjoying the security of the Alliance, Australia had to remind the United States of the strategic significance of the region.

The Keating government built upon the work of the preceding Hawke government, continuing to push for Australia’s voice to be heard in Washington while also forming strong regional relationships, particularly with influential tyrant Indonesian President Suharto. Keating believed the ‘best contribution we could make as an ally was to put our view in a lucid way, to offer the United States a framework and, above all, to be a source of ideas.’ One of his most consequential ideas, after officials prepared it for Hawke, was the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum (see chapter 4).

Keating remained proudest of proposing to President George HW Bush the idea APEC meetings should be elevated to the heads-of-government level which, after initial disinterest, the United States adopted under President Clinton.

The election of the Howard government in 1996 saw Australia’s economic or political ties with Asia less central to Australian foreign policy. Interest in what would later be called the Indo-Pacific was viewed less through a prism of economic, political and strategic integration and more through a counter-terrorism lens.

Moreover, after 9/11, the War on Terror dominated geopolitical thinking for the Alliance partners. Bush was the only president to attend every APEC summit, and his administration implemented a range of multilateral forums and institutions in Asia, including the Six-Party Talks in Northeast Asia, the US-Japan-Australia Trilateral Security Dialogue, the Asia Pacific Democracy Partnership as well as a number of free trade agreements (with Singapore, Australia and South Korea).8

The following Australian Labor government of Kevin Rudd arrived intent on making its mark on foreign policy in 2007. It commissioned a Defence white paper that was delivered in May 2009: Defending Australia in the Asia Pacific Century.[^9] Strangely, the white paper reinterpreted the common understanding of the ANZUS Treaty by noting Australia’s policy of defence self-reliance meant it should only expect the United States to come to its aid if attacked by a major power.[^10] It appeared to take Australia’s notion of self-reliance one step further by implying Australia could draw on American expertise to prepare but not necessarily to battle, noting ‘what the alliance means for our direct security is that the associated capability, intelligence and technological partnership, at the core of the alliance, is available to support our strategic capability advantage in our immediate neighbourhood and beyond.’

The Honourable Julia Gillard AC

Prime Minister of Australia (2010-13)

In 2011, on the 60th anniversary of the ANZUS Treaty, I was invited by the Speaker of the US House of Representatives, Rep John Boehner, to address a joint session of the US Congress.

I reflected on an enduring Alliance of utmost importance to Australia and the United States, our security, and our future:

‘You have an ally in Australia. An ally for war and peace. An ally for hardship and prosperity.

Geography and history alone could never explain the strength of the commitment between us. Rather, our values are shared and our people are friends. This is the heart of our alliance. This is why in our darkest days we have been glad to see each other’s faces and hear each other’s voices.

So, conceived in the Pacific War and born in the Cold War, adapted to the space age and invoked in the face of terror, our indispensable alliance is a friendship for the future.

Australia in the south, with South Korea and Japan to the north, form real Asia-Pacific partnerships with the United States. Anchors of regional stability. An alliance that was strong in the Cold War...an alliance that is strong in the new world.

When our alliance was signed 60 years ago, the challenges of the space age were still to come. The challenges of terrorism were still to come.

For 60 years, leaders from Australia and the United States have looked inside themselves and found the courage to face those challenges. And after 60 years, we do the same today.

To protect our peoples. To share our prosperity. To safeguard our future. For ours is a friendship for the future. It has been from its founding and remains so today.’

And in that same year, I addressed the Parliament of New Zealand, and observed, ‘An active, engaged America is a fundamental feature of the international system that underpins our stability, security and prosperity.’

In 2011, together with President Barack Obama and as part of his pivot to Asia, my government announced the training of US Marines in northern Australia. This was the right decision strategically for the future; one that would meet an American need and would show our preparedness to modernise the Alliance between our nations.

In the years since, the goals we set have been fulfilled and this decision continues to serve our countries by advancing security and peace in the Indo-Pacific.

I was honoured to undertake those activities of commemoration and renewal 10 years ago. Indeed, in reflecting on ANZUS while facing the foreign policy and national security challenges that come before a prime minister, I could appreciate the weight of the decision made by one of my predecessors, John Howard, to invoke the ANZUS Treaty three days after the attacks on 9/11 against the United States. Prime Minister Howard was right. Under our ANZUS commitments, we went to war in Afghanistan to support our ally the United States, which had been attacked on its own soil.

ANZUS stands as a bedrock cornerstone of the joint security of Australia and the United States.

We cannot know – after more than a year of the pandemic that has gripped our planet – what the next decade will bring. But I do know that we can meet any challenge with certainty that our ties under ANZUS will always ensure we are freer and more secure. And that we will do so as best mates.

The pivot to Asia

Any ambitions Rudd had to further embed the Alliance in Asia were enhanced with the arrival of a new US president in 2008. Barack Obama liked to occasionally call himself America’s ‘first Pacific President’ because he was born in Hawaii and partly raised in Indonesia. Also, Obama later wrote he didn’t share his old trade union supporters’ ‘instinctive opposition to free trade’ and thought ‘Clinton and Bush had made the right call in encouraging China’s integration into the global economy – history told me that a chaotic and impoverished China posed a bigger threat to the United States than a prosperous one.’ He was primed to embrace globalisation.11

While Obama was sceptical of China, a country whose ‘gaming of the international trading system had too often come at America’s expense,’ he also appreciated the United States had some politicking to do across Asia after the Bush administration’s focus on the Global Financial Crisis and the Middle East meant some Asian leaders questioned America’s relevance to the region.12 The focus of Obama’s first visit to Asia in 2009 was to reassure them the United States wasn’t aiming to contain China but ‘to reaffirm ties to the region and to strengthen the very framework of international law that had allowed countries throughout the Asia-Pacific region – including China – to make so much progress in such a short time.’13

The Rudd government exerted pressure on the new US administration. New Secretary of State Hillary Clinton wrote that during her first days on the job ‘one of my more candid exchanges was with Foreign Minister Stephen Smith of Australia.’14 Smith expressed his and Rudd’s hope the Obama administration would ‘more deeply engage with Asia.’ Clinton told him ‘that was right in line with my own thinking and that I look forward to a close partnership.’ Clinton recalled Australia became a key ally and ‘The President shared my determination to make Asia a focal point of the administration’s foreign policy.’15

Clinton and Smith solidified this determination during the Obama administration’s third AUSMIN meeting, in September 2011 at The Presidio in San Francisco. This was timed to coincide with the 60th anniversary of the signing of the ANZUS Treaty. Obama, Clinton and US Secretary of Defense Robert Gates resolved to pursue a foreign policy ‘pivot’ to Asia, a key component of which would be the rotational deployment of 250 US marines to Darwin. Rudd later wrote he, then as foreign minister, was amenable to the initiative although he believed Defence Minister Smith and new Prime Minister Julia Gillard were not. Rudd recalls Clinton saying ‘the President of the United States will not visit Australia’ as planned unless the Australian Government publicly welcomed the Darwin deployment during that visit.16

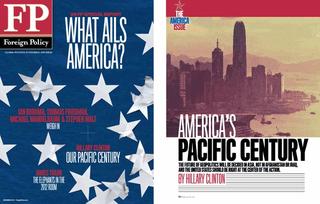

Underlying the tension about the deployment, Clinton knew a consequential US foreign policy re-emphasis on Asia was all but set in stone with the coming November 2011 publication of her ‘America’s Pacific Century’ essay in Foreign Policy magazine.17 In it, she announced ‘a pivot point’ away from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and ‘a strategic turn’ toward the ‘Asia-Pacific,’ which was now ‘the key driver of global politics.’ She argued more generally this region would be more important and more central than any other in the world for the rest of this century.18

Clinton’s essay was widely interpreted as a watershed, marking the US commitment to the region in plain words, although Clinton later protested ‘it was the word pivot that gained prominence.’19 That word was ultimately contentious. Even if the United States was saying all the right things about Asia, the word ‘pivot’ implied turning away from others, especially in Europe.

In the essay, Clinton trod warily around China, saying it ‘represents one of the most challenging and consequential bilateral relationships the United States has ever had to manage’ yet ‘the fact is that a thriving America is good for China and a thriving China is good for America. We both have much more to gain from cooperation than from conflict.’

In essence, she wrote, ‘Harnessing Asia’s growth and dynamism is central to American economic and strategic interests and a key priority for President Obama.’

Of Australia, Clinton said the United States was expanding the Alliance ‘from a Pacific partnership to an Indo-Pacific one, and indeed a global partnership. From cybersecurity to Afghanistan to the Arab Awakening to strengthening regional architecture in the Asia-Pacific, Australia’s counsel and commitment have been indispensable.’20

The United States quietly stepped back from the word ‘pivot’ preferring to call it a ‘rebalance’ towards the Indo-Pacific. The November 2012 AUSMIN meeting in Perth, the first ministerial consultation since announcing the new strategy, doubled down in the first paragraph of the customary joint communique by reaffirming ‘the value of the Australia-United States alliance in helping to shape the security and prosperity of the Asia Pacific, while also contributing to global security, good governance and the rule of law.’21 It referred to President Obama’s recent speech to the Australian Parliament ‘as part of a rebalance to the Asia Pacific’ before identifying 11 country-specific initiatives the two countries intended to implement, including support for efforts by ASEAN and China to develop a Code of Conduct for the South China Sea and working with Japan through the Trilateral Strategic Dialogue and conducting trilateral defence exercises, ‘to enhance security through air, land and maritime cooperation.’

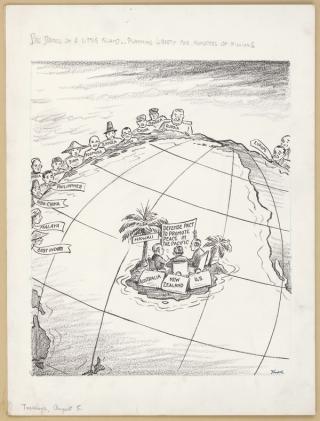

Though this recalibration to Asia as a top priority for US foreign policy was new, it was in some way destined given the many references since the Second World War to the US power in Asia, from Secretary of State Dean Acheson’s provocative speech at the National Press Club in 1950 defining an American ‘defensive perimeter’ in the Pacific22 as a line running through Japan, the Ryukyus and the Philippines, to President Clinton’s description of an ‘American Pacific century.’23 Even the notion of the Pacific being an ‘American lake’ has been oft-quoted although the source appears to be the Soviet newspaper Pravda in 1946 protesting that possible post-war treaties with Japan (the Treaty of Peace with Japan was signed in 1952) intended to turn the Pacific Ocean into an ‘American lake’ from San Francisco to the Philippines.24

Yet the quicksand of continued conflagrations in the Middle East overwhelmed the US intention to rebalance to the Indo-Pacific. Certainly, President Obama engaged more fully with ASEAN leaders’ meetings and his 2016 substantive gathering of 10 ASEAN leaders from Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam was a high watermark in US engagement with Southeast Asia. President Obama noted they agreed to ‘the principle that ASEAN will continue to be central – in fact, indispensable – to peace, prosperity and progress in the Asia Pacific.’25

Any progress on the rebalance, even talk of shifting 60 per cent of American naval assets into the Indo-Pacific, was more subtle under the Trump administration of 2017-21, which some argue achieved more in the region while talking less. Yet the president, perceived to be isolationist, eschewed free trade and the global institutions and multilateral agreements promoting it. That was clear three days after being sworn into office; President Trump signed an executive order pulling the United States out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), the US-led 12-nation free-trade pact between Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore and Vietnam. Acting on an election commitment to reverse the TPP negotiated by the Obama administration, Trump had previously said the TPP represented a ‘rape of our country.’26

In Chile in March 2018, the remaining 11 nations signed a new trade agreement called the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, or TPP11, which incorporated most of the provisions of the TPP and entered into force on 30 December 2018.27

Though President Trump prioritised an ‘America First’ strategy, the administration’s new but moderate ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific’ (FOIP) concept, rolled out in late 2017, signalled America’s commitment to economic engagement, security cooperation and rulemaking.28 The ‘FOIP’ was consistent with the Asia policies of previous administrations but the proof would be in the implementation. Or not, as it happened.

Early in Trump’s term, former US Assistant Secretary of Defense David Shear described the ‘dual crisis’ in American policy towards Asia with the Trump administration beset by a ‘crisis of distraction,’ namely domestic political squabbling, an obsession with immigration, taxation and other ‘hot button’ topics, and inadequate staffing in the bureaucracy.29 Certainly, Trump’s Secretary of State Mike Pompeo was distracted by North Korea, for instance, cancelling meetings with Indian cabinet officials to attend high-risk talks with Kim Jong-un. This dalliance with North Korea and domestic issues pulled the president’s focus, hampering efforts to construct a regional strategy.30

Even so, the Trump administration issued two major foreign policy documents that progressed the administration’s notion of strength through alliances and threats in the Indo-Pacific.

The 2017 National Security Strategy of the United States of America was unmistakably consistent with Trump’s ‘America First’ approach to foreign policy but also pointedly said ‘we will compete with all tools of national power to ensure that regions of the world are not dominated by one power...Allies and partners magnify our power.’ It also noted ‘US allies are critical to responding to mutual threats, such as North Korea, and preserving our mutual interests in the Indo-Pacific region.’31 The 2018 National Defense Strategy released by the US Department of Defense was even more pointed in its focus on China (and Russia).32

Yet in the dying days of the Trump administration (the day before the 6 January 2021 invasion of the US Capitol), it declassified a key document, its 2018 Strategic Framework for the Indo-Pacific, 30 years ahead of schedule.33 It showed an intent to ‘devise and implement a defense strategy capable of, but not limited to’ protecting Taiwan and holding its own with China. It also signalled the importance of allies such as Australia, referencing the need to ‘align our Indo-Pacific strategy with those of Australia, India and Japan’ and of a quadrilateral security relationship with India. National Security Adviser Robert C O’Brien said it was ‘being released to communicate to the American people and to our allies and partners, the enduring commitment of the United States to keeping the Indo-Pacific region free and open long into the future.’34 The Australian Broadcasting Corporation quoted a US source saying the document’s declassification was a gesture of reassurance to alliance partners, including Australia, that ‘we are not fading away but doubling down’ in the Indo-Pacific.35

The Trans-Pacific Partnership remains politically challenging for the United States. It remains on the American agenda, with President Joe Biden looking to find a way back in with a lesser agreement focused on digital trade that could bypass the required support from Congress.

Within Australia, the Alliance’s commitment to the Indo-Pacific region waxed and waned during this period. This was to be expected with six changes of prime minister, and one change of government, in 11 years. Typical was Prime Minister Gillard’s Australia in the Asian Century Defence white paper from October 2012 being purged from the prime minister’s website four months after its release when the Liberal-National Coalition led by Tony Abbott won the 2013 election.36

Gillard had commissioned two white papers to put her own stamp on foreign policy. The Australia in the Asian Century white paper, in its acknowledgment of Asia as the emerging global centre of gravity, shared the logic of the Obama administration’s renewed emphasis on this region.

The most visible enhancement of the Alliance to address regional security issues during Gillard’s prime ministership was the announcement with President Obama in November 2011 of two new force posture initiatives enhancing defence cooperation between Australia and the United States.37

From 2012, Australia hosted a deployment of US Marines in Darwin and northern Australia, completing exercises and training with the Australian Defence Force six months at a time during the dry season.38 It aimed for a rotational presence of up to a 2,500-person Marine Air-Ground Task Force (MAGTF) and was on target before the COVID-19 pandemic quelled numbers to 1,800 in 2021.39 The Royal Australian Air Force and the US Air Force also increased rotations of US aircraft through northern Australia in the Enhanced Air Cooperation (EAC) initiative, which didn’t take off until 2017, when the specifics of visiting US aircraft types and the nature of training conducted under the EAC umbrella were announced for the first time. The EAC has been an effective collaboration beyond air movements, enabling joint logistics, infrastructure development and better-enabling responses to regional crises.

The initiatives were originally governed by the 1963 Status of US Forces in Australia Agreement but a new, purpose-designed Force Posture Agreement signed at the 2014 AUSMIN, after extended negotiations over who would pay, provided a more tailored legal, policy and financial framework. Notwithstanding the delays in implementation, the 2014 Force Posture Agreement is a major new phase in building military interoperability within the Alliance, improving the capacity for each country’s air, naval and ground assets to integrate and undertake combined operations.40

Subsequent white papers by the Department of Defence in 2016 and the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade in 2017 highlighted Australia’s abiding interests in US engagement in the Indo-Pacific, ahead of two tense AUSMIN meetings in 2018 and 2019 (the AUSMIN joint communiques began referring to the ‘Indo-Pacific’ from 201741).

The 2018 AUSMIN at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University in California, was viewed as reaffirming the Alliance’s focus on the Indo-Pacific with the US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, US Defense Secretary Jim Mattis and Australian Foreign Minister Julie Bishop and Australian Defence Minister Marise Payne establishing a joint work plan that ‘advances our shared strategic interests in the Indo-Pacific, which has diplomatic, security, and economic dimensions.’42

The following year in Sydney, the US secretaries and Australian ministers constructed another step, despite issues about engagement beyond the Indo-Pacific.[^43] The gathering’s key results were increased attention on the region’s prosperity and stability through initiatives including infrastructure support, and deepening ties with Japan and India.

The Honourable Julie Bishop

Minister for Foreign Affairs (2013-18)

The principles of ‘freedom’ and ‘individual liberty’ have long been synonymous with the United States of America.

There are many facets to that, from the freedom of individuals to make decisions about their lives, to the freedom of private enterprise to conduct business, to the quest by the United States for freedom for oppressed nations. Ideals of freedom are articulated and enshrined in the US Declaration of Independence and its Constitution.

The Statue of Liberty has stood on Ellis Island for more than 130 years, as a symbol of freedom – a nation welcoming migrants and those seeking safe refuge from persecution.

It’s the reason so many people all over the world have sought to become citizens of the United States in search of a better life for themselves and their families.

The United States is seen worldwide as a cradle of advancement for those seeking to participate in an egalitarian society, where all people are created equal, with opportunities to rise from humble beginnings to the highest levels of success in business, politics, military service and across society.

This remains the case, despite ongoing debate within the United States of the strengths and weaknesses of its political and economic systems.

The relationship between the United States and Australia has always been close and warm, despite being separated by the world’s largest ocean of the Pacific. The ANZUS Treaty is a formal manifestation of that relationship.

As former colonies of Britain, there is a shared language and culture. Our governments were founded on a model of federalism, with two chambers in our respective Parliament and Congress.

The frontier spirit that inspired early settlers of the United States was embraced by British migrants to Australia, although many were reluctant travellers.

Just over a century ago, our defence forces fought side by side during the First World War, although the vast distance between our nations prevented closer ties until technology and necessity intervened.

In the dark days of the Second World War, in January 1940, Australian Prime Minister Robert Menzies sent Richard Casey to Washington to establish our first diplomatic post outside London, from where our foreign relations had previously been conducted.

One year later, President Roosevelt gave his famous State of the Union address to Congress, in which he articulated the ‘four freedoms’ to which all humanity was entitled.

Freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear became a rallying cry to those suffering under the oppression of the invading armies of the Axis powers.

These fundamental principles were incorporated into the Atlantic Charter in August 1941 and the Declaration by the United Nations in January 1942, and the drafting of the United Nations Charter in 1945.

They are also credited with inspiring the development of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted in 1948.

It is these ideals that inspired the Marshall Plan to rebuild war-torn Europe, including former enemy (western) Germany and an associated plan for Japan.

The United States believed it had a responsibility to promote freedom among the peoples of nations that had been under the heel of authoritarianism.

This commitment to individual freedom has been a guiding light throughout the world, particularly in the years since 1945.

With the support of other nations, the United States has been the primary instigator, sponsor and supporter of the rules-based international order.

Designed to prevent a repeat of the horrors of global conflict, it is a framework of organisations, institutions, treaties, conventions, laws and norms, underpinned by international law, that governs the behaviour of nations towards each other.

This order facilitates the conduct of international relations and supports the peaceful resolution of disputes.

The rules-based order survived the challenges of the Cold War, however, it’s again under pressure from global shifts in relative economic and military power.

Export-orientated trading nations like Australia depend on a rules-based international order for fair access to the markets of other nations and the free movement of people and goods.

During the five years I served as Australia’s Foreign Minister, it was a recurring theme in many parts of the world that notwithstanding an increase in great power competition, there was a desire for greater engagement with the US Government and its private sector.

Investment from US companies is regarded highly in the vast majority of countries and particularly in developing nations. There is a huge well of goodwill towards the United States and the role it continues to play internationally. It is vital that is maintained through ongoing high-level engagement globally.

Esteemed former US Defense Secretary Jim Mattis has regularly called for a greater focus on diplomacy as the best way to peacefully resolve tensions internationally.

The great strength of the United States is not only economic and military power, but also its unparalleled global networks of treaties, allies and partnerships.

There is concern among some nations that the United States is showing signs of potentially retreating to an isolationist posture of past eras.

That narrative can be countered with a resurgence of sustained high-level engagement from US leaders and officials and importantly from US private-sector investors.

Nations seeking to grow their economies and develop their physical and human capital will continue to seek mutually beneficial international relationships, and the United States can continue to be the bedrock of their development and success.

The Quad

Ongoing rapid geostrategic change in the Indo-Pacific led the United States to revisit ways of ‘thickening’ its alliance and partner network in the region. The declassified 2018 US Strategic Framework for the Indo-Pacific noted the need to ‘align our Indo-Pacific strategy with those of Australia, India and Japan,’ of deepening trilateral cooperation with Japan and Australia, and a quadrilateral security relationship with India. These aspirations have been realised in recent years, most particularly the rejuvenation of the Quad.

The four-way, security-focused partnership had its genesis in the aftermath of the devastating 2004 Boxing Day tsunami, where Australia, the United States, Japan and India coordinated an effective emergency response in a matter of weeks for devastated regions in South Asia and East Africa, where more than 225,000 people died.44

Shinzo Abe propelled the idea of a Quad in his book, Utsukushii Kunihe (Toward a Beautiful Country), published shortly before he became Japan’s prime minister in 2006.45 He re-introduced it in 2007 while addressing the Indian Parliament, floating the idea of a ‘broader Asia’ partnership to create an ‘immense network spanning the entirety of the Pacific Ocean, incorporating the United States of America and Australia. Open and transparent, this network will allow people, goods, capital, and knowledge to flow freely.’46

Abe’s proposal evolved into a defence arrangement enhanced by a major joint military exercise between the four nations47 when, a month later, the United States, Japan and Australia were invited to the annual India-US Malabar naval exercise in the Bay of Bengal.48

The Quad initially intended to facilitate, as Abe described it in 2006, an ‘Asian Arc of Democracy,’ across a number of Central and Southeast Asian countries, other than China.49 Prime Minister Abe also described the initiative as a ‘democratic security diamond’ in December 2012.

The group of four held its inaugural meeting on the sidelines of the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) gathering in Manila in 2007, before it met resistance. This first meeting was unpublicised, so as not to upset the elephant not in the room, China. Nevertheless, China sent a démarche, or diplomatic note, to Tokyo, New Delhi, Canberra and Washington asking why the initiative was being established, before Chinese President Hu Jintao sought clarification from Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh at the G8 Summit in Germany in June.50

Each nation dissembled slightly; Australian Defence Minister Brendan Nelson said Australia favoured limiting the initiative to trade, culture and other issues outside defence and security.51 He also told The Australian Financial Review in July 2007 he had assured his Chinese counterpart, Cao Gang Chan, Australia was not interested in forming a security pact with the United States, India and Japan as a regional buffer to China.52

The change of Australia’s government in November 2007 halted the Quad, for the medium term at least, with the new Prime Minister, Kevin Rudd, withdrawing Australia from the agreement in his first year of government due to concerns about China’s displeasure.

Rudd has since argued his reasons for abandoning the Quad were the ambiguities in the original proposal, the illogic of ignoring China, seeming disinterest from new Japanese Prime Minister Yasuo Fukuda and a distracted United States.53

Almost a decade later, Japanese Foreign Minister Tarō Kōno proposed a gathering of the four foreign ministers in the margins of an upcoming summit and, in November 2017, on the sidelines of ASEAN in Manila, senior officials from the four countries met officially under the auspices of the revived Quad.54

The four leaders of the Quad countries held their first meeting in March 2021 — albeit virtually, due to pandemic concerns — initiated by President Joe Biden; previously only foreign ministers or defence chiefs attended. This was a visible vote of confidence in the arrangement because Biden prioritised this within 100 days of his inauguration as the first multilateral summit he hosted as president.55 In a joint statement, Modi, Japanese Prime Minister Suga Yoshihide, Biden and Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison reaffirmed ‘our commitment to quadrilateral cooperation between Australia, India, Japan, and the United States’ and described ‘a shared vision for a Free and Open Indo-Pacific’ and a ‘rules-based maritime order in the East and South China Seas.’ The initial vision included work on vaccine diplomacy and infrastructure.

The development of bilateral and trilateral relationships among the Quad nations has also blossomed with the AUSINDEX joint naval exercise between Australia and India growing and the joint Australia-US exercise, Talisman Saber, adding Japan. The previous bilateral military exercises, and special strategic partnership between Japan and Australia, including Japan’s increased participation in the Southern Jackaroo (2017) and Kakadu (2016) multilateral exercises in Australia, were crucial impetus for the Quad.56

Aligned interests drove the Quad’s establishment. Those interests also drove the announcement in September 2021 of Australia’s enhanced trilateral security partnership with the United Kingdom and United States (dubbed AUKUS). The centrepiece of the AUKUS pact will be the sharing of UK and US defence technology to allow Australia to construct at least eight new nuclear-powered submarines. The enhanced agreement denotes deeper cooperation on security and defence capabilities between the three countries as they project a more powerful posture in the Indo-Pacific.

China’s economic coercion of Australia and its aggressive diplomacy helped give the Quad and the AUKUS focus and purpose after nearly fading away entirely, with Japan its sole champion. China’s modern engagement contrasts with its previous penchant to keep a low profile in diplomatic affairs. Amid China blacklisting Australian imports, applying pressure on Japan’s naval movements and allowing border disputes with India to result in the deaths of Indian soldiers, White House Coordinator for the Indo-Pacific Kurt Campbell in July 2021 criticised China’s approach to Australia, saying he saw ‘a harshness in their approach that appears unyielding.’57

A growing convergence in foreign policies among the four states, founded on their shared interest in a free and open Indo-Pacific and a rules-based international system, resulted in a stronger Quad, buttressing and extending the US-Australia Alliance.

The Honourable Stephen Smith

Minister for Defence (2010-13), Minister for Foreign Affairs (2007-10)

I had the great privilege of serving in the National Security Committee of Cabinet as Australian Foreign Minister, and then Defence Minister, from 2007-2013.

This saw me attend AUSMIN over those years and provided the opportunity to deal directly with US counterparts and other officials on Alliance operation and cooperation, and, as well, to celebrate significant Alliance milestones, such as the 70th anniversary of diplomatic relations, the 60th anniversary of the ANZUS Treaty, and the 25th anniversary of the establishment of AUSMIN itself.

The breadth and depth of what AUSMIN considers is underappreciated. AUSMIN communiques themselves and the associated documentation from the meetings are also a much underappreciated treasure trove of what is happening in our Alliance relationship, and in part reflect what was top of mind in the relationship at the time.

The communiques from those years are redolent with what you would expect – Afghanistan and Pakistan, North Korea and Iran nuclear proliferation, the emergence of China, and greater engagement with India, to mention just a few.

But through this period, they also draw attention to less well appreciated but deeply significant Alliance practical cooperation measures, which at the time we described as ‘21st century security challenges.’

This cooperation ranged from space, satellite and defence communications infrastructure to cyber.

It included our Joint Statement on Cyberspace, our Space Situational Awareness Partnership and Joint Statement on Space Security, our Defence Satellite Communications Partnership and Combined Communications Gateway, the establishment and deployment of the Jointly Operated US C Band Radar at the Harold E Holt Naval Communications Station, and the relocation of an advanced US Space Surveillance Telescope to Australia.

Perhaps the most publicly appreciated AUSMIN work through that period was the US ‘rebalance’ and its Global Force Posture Review, complemented in Australian domestic terms by our own Force Posture Review in 2011, our first since the 1980s.

This body of work saw President Obama’s visit to Australia in late 2011, and the announcement of enhanced Alliance practical cooperation measures, headlined by the rotation of marines through Darwin, but underlined by greater utilisation of Australian airfields in our north and west through greater rotation of US aircraft, and the promise of greater US Navy utilisation of Australia’s Indian Ocean naval base at HMAS Stirling, south of Perth.

What looked publicly like a seamless announcement was, of course, the culmination of many months of detailed work and discussion variously between ministers and officials, most of it rudimentary and polite, but some of it robust without perhaps ever becoming impolite.

A number of our US colleagues took time to appreciate the rotation of marines actually had to mean rotation! Anything more than that would, of course, be perceived as a US base, not a joint facility under the umbrella of the full knowledge and concurrence principle, entrenched into our Alliance from Prime Minister Bob Hawke’s statement to the Australian Parliament in 1984, and reaffirmed by successive Australian governments since.

The rebalance reflected a changing world and the rise of the Indo-Pacific, which emerged as part of Australian policy analysis in 2008, embedded as formal Australian strategic doctrine in our 2013 Defence white paper, and which persists to this day, having been adopted by most nations in the region.

This emerging Australian Indo-Pacific analysis had been very influential on Secretary of State Clinton, whom Australia urged to sign up for ASEAN’s Treaty of Amity and Cooperation, and then join the most important part of Indo-Pacific regional architecture, namely, the East Asia Summit, which Australia then helped facilitate in cooperation with Indonesia and Singapore in 2011.

Finally, of course, is the great personal and professional pleasure and regard which comes from working with great Americans and such great friends of Australia from both sides of the US aisle. In my time, in particular Condoleezza Rice, Bob Gates, Hillary Clinton, Leon Panetta, Chuck Hagel and Ambassador Jeff Bleich.

Not to mention the occasional bit of fun that comes from a ‘hometown’ visit to Perth, Australia’s Indian Ocean capital, variously by Condoleezza, Hillary and Leon. Lasting impressions and outcomes can also come from a ‘hometown’ visit. In particular, Secretary Clinton announced the establishment of the Perth USAsia Centre in the margins of AUSMIN 2012 in Perth, which included her emphasis of the Indo-Pacific lexicon, a shift that ultimately became reflected in US official language, including the renaming of the Pacific Command to US Indo-Pacific Command in 2018.

Read Chapter 9 of The Alliance at 70: The evolution of the Alliance