In 1969, when one-fifth of the world’s population – an estimated 650 million people – watched transfixed as Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin set foot on the Moon, few realised the images were a fortunate and almost last-minute result of the US-Australia Alliance.1

The collaboration between Australia and the United States on space exploration is both by design and default. Australia’s position in the southern hemisphere across the Pacific Ocean from the United States means it is a logical communications partner. The first passage of almost all orbiting spacecraft lifting off from Cape Kennedy is within sight of Western Australia.

Back in 1969, the key National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) deep space tracking facility in Goldstone, California required a network of at least three tracking stations, spaced 120 degrees apart in longitude, if it was to maintain continuous coverage of orbiting spacecraft as the Earth turned.2 Australia was in the right longitude, as was a third station in Spain.

Australia had other advantages to support lunar and space programs beyond its shared English language and broader relationship with the United States. Most particularly, it was a world leader in radio astronomy after the Second World War, with Australian engineers and scientists expert in designing and building sensitive radio receivers and antennae.3

The changing geopolitical environment also eased the way. In the wake of the Second World War, Prime Minister Ben Chifley returned from the Prime Ministers’ Conference in London in 1946 realising Australia needed to assume a greater share of the ‘burden of armaments’ resting upon the Commonwealth, particularly in the southwest Pacific.4

While that led to the regional security agreement that would become ANZAM (for Australia, New Zealand and the Brits in Malaya),5 Chifley was increasingly looking towards the United States for defence. Even so, the Woomera Rocket Range was established in South Australia in 1947 as a testing ground for the British, who were devastated in the Second World War by Germany’s advanced V1 and V2 rockets.6

The Robert Menzies government expanded defence science research, particularly in guided missiles with the United Kingdom. So, by the mid-1950s, as other nations moved to prepare launching satellites, Australia had solid technical expertise beyond its size. This helped when the United States looked globally for suitable communication sites and staff.

As space became the new frontier, the US Department of Defense in 1955 accepted a Navy proposal to send a satellite into orbit during the International Geophysical Year, 1958, for a scientific experiment.7 Project Vanguard laboured without urgency until the Soviet Union launched its first Sputnik satellite in 1957. The world was now on high alert as the Cold War escalated.

Early the following year, US President Eisenhower called for the creation of a national, civilian space agency, NASA.8 When he signed the Space Act on 29 July, Australia was an interested participant, with the Australian Weapons Research Establishment already operating two satellite tracking stations at the Woomera Test Range in South Australia for the United States.9

The competitive tension with the Soviet Union focused efforts, and Australia’s allegiance was clear given it terminated diplomatic relations with Russia in April 1954 after the Petrov espionage affair (in which a Canberra-based KGB spy defected; see chapter 2).10

Australian sites began tracking satellite orbits after a Baker-Nunn camera was transported to the Minitrack station at Woomera in 1957.11 Its first satellite observation on 11 March 1958, was Sputnik 2, the second Russian spacecraft launched into orbit, this one carrying the doomed dog, Laika, which died on her fourth orbit.12

The Minitrack station then tracked the first satellite launched by the United States, Explorer I, after its launch from Cape Canaveral in Florida on 31 January 1958.13 The Australian tracking stations were staffed with Australian personnel.

As NASA accelerated the Deep Space Program, a technical committee visited Australia the following year with the express purpose of selecting a suitable site for an 85-foot ‘dish’ antenna that would become one of three in a global network tracking vehicles travelling in deep space.

Project Mercury, the first American attempt to put a man in space, then gave further momentum to the initial Australian-US Space Cooperation Agreement (1960).14 The existing Department of Defense tracking stations weren’t able to provide comprehensive coverage of flights to meet safety standards for human flights, so in 1959 NASA made plans to add eight more tracking stations, including proposals for two in Australia.

The first at Island Lagoon near Woomera was the first full deep space tracking station outside the United States for the Deep Space Instrumentation Facility (DSIF).15 The designated DSIF-41 was not only approximately 120 degrees in latitude from Goldstone but was helpfully in the southern hemisphere at a latitude of less than 35 degrees.

In 1962, a second smaller facility near Western Australia’s southwest coast, at Muchea, north of Perth, was constructed.16 It would be critical determining an accurate orbit for space flights, with one US Office of Space Flight Operations estimate calculating a Moon landing error of 13 miles without it.

NASA planned another 26-metre diameter antenna in Australia to support the Deep Space Network, the Satellite Tracking and Data Acquisition Network (STADAN), and the Manned Space Flight Network (MSFN) but Woomera’s Deep Space Station was deemed unsuitable due to its remoteness from a major city.17

In 1962, Canberra was selected principally because it was a relatively noise-free area for radio frequencies18 – and it was expected to grow as the nation’s capital. A suitable site was found 16 kilometres southwest of the city of Canberra, at Tidbinbilla, which is now the Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex, operated by CSIRO on NASA’s behalf.19

NASA invested millions in these tracking facilities, all staffed and operated by Australians under a nation-to-nation treaty signed in February 1960.20 In the year of the Moon landing, Australia had more NASA tracking stations than any country except the United States.21

But the big ‘dish’ that pulled focus in 1969 was not yet one of them.

The science of the transmission

Initially, the Apollo 11 lunar module wouldn’t carry a TV camera because keeping flight weight down was the priority.22

And NASA didn’t know whether it could send a TV signal 384,000 kilometres back from the Moon given it would share bandwidth with more vital voice, telemetry, and biomedical data signals – from one 66-centimetre radio dish on top of the lunar module that used 20 watts of power, the equivalent energy output as two LED light bulbs or fridge lights.23

Westinghouse Electric Corporation spent five years developing a low-energy, three-kilogram lunar TV camera.24 NASA only decided to broadcast a TV signal in June 1969, days before Apollo 11’s flight plan was approved on 1 July. The Westinghouse camera that captured Neil Armstrong’s famous first footstep is still on the surface of the Moon.25

There had also been a change of plan because the astronauts were now scheduled to rest for a few hours after landing, meaning the moonwalk would start about 10 hours later. Consequently, the Moon would have set at Goldstone but be high overhead at Parkes, so Parkes was upgraded from a back-up (because it only received signals and didn’t transmit them) to the prime receiving station for the TV broadcast, given its large collecting dish could provide improved gains in signal strength and high-quality TV output.26

The size of the telescope captured many radio waves but its terrific receiving systems also helped.

The TV vision was transmitted from the Moon as radio waves, with those incoming waves reflected off the surface of the Parkes dish27 and up to its ‘focus cabin’ above it where feedhorns captured the radio waves and turned them into electrical signals.28 Both feedhorns were designed by CSIRO engineer Dr Bruce Thomas.

NASA instigated secure, reliable communications for its overseas tracking stations with Australia’s international telecommunications operator, the Overseas Telecommunications Commission, establishing a satellite earth station in Carnarvon in 1967 and a second earth station at Moree, in northwest New South Wales, in March 1968.29

These stations transmitted signals from the Apollo 11 mission to communications satellites, which relayed them to the United States. Carnarvon sent telemetry from experiments on the Moon’s surface, while Moree sent the TV pictures.

Among the many discoveries of the Apollo 11 Moon landing was the realisation standard TV signals could travel all the way from the Moon to Earth.30 This led to clearer, sharper broadcasts on subsequent Apollo missions.

Parkes

The Parkes Radio Telescope was completed in 1961 with American heft key to its existence. As Australians specialised in developing radar and communications technology after the war, the head of CSIRO’s Radiophysics Laboratory, Edward George ‘Taffy’ Bowen, suggested the creation of a radio telescope that would advance radioastronomy discovery.31

Bowen had worked on radar development in the United States during the war – with his seminal work contributing to key wins in the Battle of Britain and Battle of the Atlantic.32 He later persuaded two American philanthropic organisations, the Carnegie Corporation and the Rockefeller Foundation, to fund half the cost of a telescope before the Menzies government funded the rest.33

He selected the Parkes site for its distance from Sydney and clear skies, stable geology and low radio-frequency interference. After five years of design and building, it opened on 31 October 1961 when Bowen said ‘...the search for truth is one of the noblest aims of mankind and there is nothing which adds to the glory of the human race or lends it such dignity as the urge to bring the vast complexity of the Universe within the range of human understanding.’34

“...the search for truth is one of the noblest aims of mankind and there is nothing which adds to the glory of the human race or lends it such dignity as the urge to bring the vast complexity of the Universe within the range of human understanding.”Edward George ‘Taffy’ Bowen, CSIRO Chief of Radiophysics at the opening of the Parkes Radio Telescope 31 October 1961

NASA had been watching; indeed, it would copy the basic design of the 64-metre, 1,000-tonne dish for its tracking dishes built at Goldstone, Madrid, and Tidbinbilla.35 NASA asked CSIRO repeatedly if it could use Parkes occasionally for spacecraft tracking and incorporate it into its Deep Space Network but CSIRO refused, saying its job was astronomy beyond the orbits of Earth!36

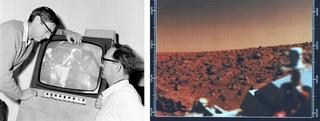

Nevertheless, CSIRO agreed to track spacecraft when an extra dish would give much-needed sensitivity. In 1962, Parkes helped track NASA’s first successful interplanetary mission, the Mariner 2 spacecraft sent to Venus, and then the Mariner 4 flyby of Mars in 1965, which returned the first close-up photos of the planet’s surface.37

But CSIRO didn’t receive acknowledgments by NASA of its contribution to the projects, so it refused two requests during the mid-1960s by NASA to assist its space program.38 NASA tried again in 1968, asking whether Parkes would assist Goldstone for the planned Apollo 11 moonwalk.

CSIRO couldn’t refuse this time because human lives were at stake. It pledged to do everything necessary to aid the mission’s success, even if the Director of the Australian National Radio Astronomy Observatory John Bolton’s recalcitrance offered only a one-line agreement: ‘The Radiophysics Division would agree to support the Apollo 11 mission.’39

Consequently, the Australian contribution would include the main tracking station at Honeysuckle Creek, near Canberra, where a 26-metre dish was NASA’s prime antenna in Australia for supporting human spaceflight and astronauts on the Moon.

NASA’s nearby Deep Space Network station at Tidbinbilla also had a 26-metre antenna but with a more sensitive radio receiver that would enhance Honeysuckle Creek, and ultimately track Michael Collins in the Columbia orbiting command module during Apollo 11.40 And in Western Australia, Carnarvon’s smaller nine-metre antenna would track the Apollo spacecraft when it was in the lower Earth orbit, as well as receive signals from the lunar surface experiments.41

The Parkes radio telescope would support the astronauts while they were on the surface of the Moon yet, initially, this would not include a television transmission back to Earth.

Incredibly, NASA had no plans to televise what became arguably the greatest human achievement of the 20th century. And as late as 1966 there was no way to get live television signals from Australia to the United States.

After the Apollo 11 mission successfully launched, but before landing on the Moon, chaos reigned for a short period in Australia.

Firstly, two days after launch, a fire at the Tidbinbilla station’s transmitter meant Honeysuckle Creek would now have to track the lunar module, while Tidbinbilla maintained communications with the command module.42

On 21 July, Neil Armstrong safely landed the lunar module, Eagle, on the Moon, in the view of both the Goldstone and Madrid dishes, and Armstrong’s immortal ‘Tranquility Base here, The Eagle has landed,’ was transmitted by radio, with the lunar TV camera being saved for a crucial moment.43

An excited Armstrong convinced Mission Control to abandon the scheduled ‘sleep period’ to allow an attempt of his first step early, as soon as he and Buzz Aldrin were in their spacesuits. This was six hours earlier than anticipated. Consequently, the radio dishes in prime position for the scheduled moonwalk – Parkes and Honeysuckle – would need to be repositioned lower to capture the Moon earlier in the day. But while Honeysuckle’s tracking dish could be angled to the horizon, at zero degrees, Parkes’ bigger dish could only be angled down to 30 degrees above the horizon. So Honeysuckle’s smaller dish would receive broadcast signals two hours earlier than Parkes.

As this was happening, an unexpected visitor arrived in a Bentley at Honeysuckle: Prime Minister John Gorton.44 After Honeysuckle’s dish was moved out of its tracking alignment for the prime ministerial photo opportunity, he departed around 10am.

Even worse, just at that moment, a wild windstorm hit Parkes, buffeting the bigger dish with gusts of 100 kilometres an hour.45 Normally, telescope operations would be closed in such conditions but this was not a normal event. Fortunately, the astronauts took longer than expected to put on their spacesuits and depressurise the lunar module in preparation for the moonwalk, allowing the Moon to rise a bit higher in the sky for a better line of sight in Australia.

As the winds subsided and Aldrin activated the lunar TV at 12.54pm AEST, the less sensitive offset receiver of the two in Parkes’ focus cabin saw the Moon, and the three antennae in Goldstone, Honeysuckle Creek and Parkes received the signal simultaneously.

The images were not smooth though. The Goldstone signal was a harsh, high-contrast image and initially upside down because the TV camera on the lunar lander was mounted upside down to make it easier for the astronauts to grab.46 A Californian technician forgot to flip the switch to invert the image. The Americans persevered with the Goldstone image, thinking its big dish would receive a better picture but, as Armstrong descended the ladder, they decided to switch the image to Honeysuckle’s, wherein 600 million people saw a clear image of Armstrong on the ladder, right side up, as he stepped backwards off the Eagle landing pads, placing his left foot in the lunar dust and intoning: ‘That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.’47

Eight minutes into the broadcast, the Moon rose high enough to be received by Parkes’ main, on-focus receiver and the TV quality improved, so Houston switched to Parkes and stayed with its signal for the remainder of the two-and-a-half hours of the moonwalk while Honeysuckle focused on communications with the astronauts and receiving crucial telemetry data.48

The televising of the Apollo 11 Moon landing was a high achievement in Australian-American collaboration, combining expertise, nimble decision-making, pragmatism, and just a little luck.

It presaged decades of continued collaboration between the two countries in space exploration, global communication and satellite intelligence (some outlined in the previous chapter).

Beyond the Moon

While US tracking stations in Australia during the 1970s were consolidated, the importance of the Tidbinbilla site grew.

Honeysuckle Creek continued to aid the remaining Apollo flights to the Moon until the lunar program finished in December 1972, including the doomed Apollo 13 mission and four subsequent Apollo missions.51 In 1975, Australian sites supported the Viking 1 and Viking 2 missions to Mars and subsequent successful landings of two spacecraft on the surface of Mars.52 Later, Tidbinbilla and Parkes assisted the 1977 Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 missions to the outer planets before the successful 1978 mission to analyse the atmosphere of Venus, Pioneer 12 and Pioneer 13.53 Tidbinbilla was pivotal, due to the alignment of the solar system at the time, in relaying seminal images of Jupiter’s Moon lo, which was found to have active volcanos – the first outside Earth.54 For the same reason, the station was crucial when Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 encountered Saturn, discovering that it had 60 moons orbiting the planet.

And most recently, in 2018-19 the Parkes telescope supported NASA’s Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex in receiving data from Voyager 2 as the spacecraft crossed into interstellar space.55

Collaborations in Earth’s orbit also impacted fields beyond space exploration. In 1970, NASA launched the University of Melbourne’s Australis-OSCAR 5 satellite, which was built by students in 1966 and sent to the US Air Force in 1967 before its launch by NASA in 1970.56

Satellite launches began to have a profound effect on commerce when NASA began providing satellite images of Earth after the launch of Landsat 1 in 1972 and Landsat 2. They provided new data about the surface of the Earth, allowing viewing, mapping and analysis of great swathes of the Australian continent. Australia’s expertise in aircraft-mounted remote sensitive equipment meant it became a sophisticated user of these images, and subsequent innovators in processing and interpreting satellite data and remote sensing, particularly for mineral exploration and mining.

Satellite imagery had to deal with the unique characteristics of the Australian landscape.57 While NASA’s imagery used average global brightness, Australia is much brighter than most other countries, causing many surface details to be lost in the glare. So Australia obtained the original magnetic tapes of the satellite digital data to process it itself.

Consequently, in 1974, CSIRO employees produced a better-optimised set of images that became the global benchmark for Earth observation algorithms due to their accuracy.58

As mining companies such as BHP, CRA and Western Mining used more satellite data while trying to hide where they were inquiring, they too began to process and develop expertise in their own imagery, along with CSIRO and the Division of National Mapping.59 This had a profound effect on Australia’s ability to exploit its resources and become a mining powerhouse.

The working relationship between the two nations continues apace. In 2017, Australia and NASA signed a treaty covering space vehicle tracking and communications facilities,60 while CSIRO continues to work with NASA at the Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex, supporting communications for the landing of rovers on Mars, the arrival of New Horizons to Pluto, and the entry of Juno into orbit around Jupiter.

The collaboration took a more tangible step in 2019 with the new Australian Space Agency[^61] and NASA partnering on future space cooperation, including the chance for Australia to join the United States’ Moon to Mars exploration.[^62]

Rob Sitch

Director and co-writer of The Dish (2000) and The Castle (1997); Director, co-writer and star of Utopia (2014-present), The Hollowmen (2008) and Frontline (1994-97)

The recently released magisterial history of US state dinners, Fred Ryan’s Wine and the White House, has a cover photo of the last dinner setting before the pandemic.

It’s a magnificent scene in the Rose Garden. You instinctively assume it’s for the Queen or the President of France. However, if you look closely you’ll notice it’s in honour of the Australian Prime Minister.

The relationship between the two countries has a way of popping its head up. Similarly, in the historic list of global treaties the United States signed after the Second World War, not long after NATO comes ANZUS!

This may be an odd admission from someone in my field but I once spent quite a bit of time studying the ANZUS Treaty. It was going to be the centrepiece of one episode of a comedy series we made in 2008. Our interest was piqued by a simple fact; the Treaty was only three pages long (half if you take out the names of signatories and obligatory headings)!

That’s not to diminish its stature. There was something comforting about its brevity and practicality. More so today when an Apple account requires you to agree to 300 pages of terms and conditions and pretend you’ve read them.

That said, at the time of our idea, it was doubtful anyone outside a think tank had read the Treaty in years. It had shrunk to a notion, an understanding. Somewhere between a shibboleth and an emoji. That too was practical. The details weren’t the point, the gist of it was. And everyone in this country understood the gist.

In this episode, once our fictional officials discovered its modest length, they set about finding ways to add to its heft. They threw in Wikipedia entries, biographies, academic articles and spiels from every half-connected dignitary they could track down (don’t worry…the irony of my involvement here is not lost on me).

The attempt was to create a leather-bound limited-edition, two-volume tome with accompanying coffee-table book. A bit like the Treaty itself, admired but never read. If you’ve got to this paragraph you’ve proved us wrong!

But back to the gist. Aussies couldn’t come up with a single quote from the Treaty but they could summarise the point: in an unstable world still emerging from history’s greatest conflagration, Kiwis, Aussies and Yanks seem to get along…and we seem to agree on what totalitarian forces look like…and we shouldn’t let that go to waste.

Australians have had a lot to do with Americans over the past 150 years. From the Californian gold rush on, examples pop up everywhere. Mark Twain toured here in 1895 and in his writings seemed less mystified by us than his own countrymen.

Many Aussies have a personal connection. During the Second World War, my father was briefly seconded to fly in US Catalinas. ‘Fine aviators,’ he would say. He shared airbases with US forces in the South Pacific: ‘They had a jeep to go to the toilet!’ There it was in a nutshell; respect for the skills and the scale of the US military machine but still proud of his own mob’s ability to do more with less.

That was the DNA of our film The Dish. It was based on a forgotten Australian involvement with the Apollo program.

By chance, Australia had some rather good radio telescopes. Our scientists and NASA had a lot to do with each other during those critical years. All the TV pictures from Apollo 11 came via Australian installations. This surprised many Americans and even more Australians who had never heard of this fact.

One only had to look at the photos from the period to be amused by the mismatch. Technical experts at Mission Control in crisp white shirts and ties while in outback Australia, an expert radio astronomer seemed to be dressed as a farm labourer. On the one hand, the greatest and most expensive act of experimental science and exploration in history and on the other side of the world a local guy ready to hand dig a trench in order to make a giant satellite dish exceed its specifications. It was easy to imagine admiration going both ways.

There’s a little-told story from that time. An orbiting American astronaut found himself over the west coast of Australia. He was fondly remembering an Aussie friend when he decided to send him a cheerio. The officer who received it at the isolated communication station in northwestern Australia converted it into a telegram. Then he had an issue. It needed a sender’s address. So he simply wrote, ‘from Space.’

There is the US-Australia connection in one exchange: comity, practicality and friendship.

There were other aspects to the ANZUS Treaty that surprised us. Given the number of times it has been proudly referenced in this country, you’d think its invocation would be as regular as the Olympics. Despite a number of our prime ministers being only too keen to announce troop deployments, there’s only one instance where the Treaty was invoked and that was led by us. This seems partly by design.

The great American war-time General, George Catlett Marshall, who was Secretary of Defense at the time, seems to have had a hand in cooling some of the original language. Having overseen the allied effort in the Second World War, he wasn’t keen on agreements that encouraged a reflex call to arms. So the Treaty calls on signatories to ‘consult’ and ‘act’ without specifying what that means. It may well be the key to its longevity.

Marshall seemed to play a role in everything around that time. A few years earlier he stepped up to the podium for the 1947 Harvard Commencement and announced the ‘Marshall Plan.’

In the lead up to the 50th anniversary of that world-changing event, I walked around Harvard Yard trying to find a plaque or a statue marking the occasion. I failed.

We’re very good at commemorating war but we probably need to be better at commemorating ideas that secure peace.

To the extent that the ANZUS Treaty was aimed at security rather than conflict, it’s well worth choosing the 70th anniversary to study it anew.

And maybe plonk a plaque somewhere!

Read Chapter 4 of The Alliance at 70: Commencing consultations