Australia’s experience during, and after, the Second World War drove its desire to formalise a security treaty with the United States. An understanding that allies could help defend Australia was a key driver yet Australia also felt overlooked. Australia didn’t access the higher levels of strategic planning during the war, despite its commitment and sacrifice, and as the new world was remade, Australia was a passive observer.

Initially Australia was a passive observer in global intelligence gathering. In the decades following the Second World War, the Cold War between the Western democracies and the Soviet Union became global in its reach and driven by rapid technological innovation. New technologies for communication — and intercepting communications — ensured signals intelligence became a crucial element of national security through the Cold War, and became a valuable and significant facet of the US-Australia Alliance.

By necessity, this facet of the Alliance is shrouded in secrecy and hence is often subject to speculation and intrigue, and at times, scepticism and controversy. The available historical records show a maturing of US-Australia collaboration within intelligence, with moments of deft political management and policy innovation running parallel with technological advances and geostrategic circumstances, consequently changing the agenda for the Australian and US intelligence communities.

From less sophisticated origins in the years following the Second World War, Australia has become a more capable and assertive Alliance partner in intelligence collaboration with the United States.

Six decades later, in 2004, President Bush increased Australian and British access to its highest levels of intelligence by sending a one-page presidential directive to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and US Defense Department to relax its ‘NOFORN’ (to be seen by no foreign eyes) classification on American intelligence to them.1 For Australia, this was both a reward for continued political and defence support after 9/11 and also recognition of the key role Australia played in signals intelligence, or intelligence gathering through intercepting communications.

The rise of intelligence sharing

Australia’s location provides a formidable advantage in satellite tracking, communications and control (particularly in space exploration, as explained in the following chapter). Australia’s status as an American ally and as a stable, secure democracy led to this advantage being exploited, by both Australia and the United States, to the long-term benefit of the Alliance.

Cooperation in signals intelligence (SIGINT) helped create or enhance a number of significant partnerships branching from the ANZUS Treaty. They include the Five Eyes (FVEY) intelligence-sharing arrangement between the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand, and the emerging and increasingly consequential Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (the Quad) arrangement between the United States, Australia, India and Japan.

The Australian Government was responsible for national security and intelligence after Federation in 1901 but there was little need for concerted efforts until domestic threats were identified after the First World War. Perceived threats included the Communist Party of Australia, the anti-left New Guard in the early 1930s and the far-right political movement, Australia First in 1941-42.2

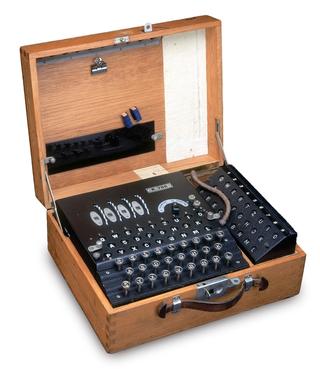

After seeing the British break the German Navy’s encrypted messages during the Second World War, Australia changed its federal intelligence requirements. The British effort to crack the Enigma code decided the pivotal Battle of the North Atlantic and showed the value of information security. The United States also broke Imperial Japanese Navy codes, which was key to its victory in the Pacific’s pivotal Battle of Midway.

In the wake of the Second World War, the Australian Department of Defence shared national intelligence assessment functions between the three Australian Defence Force services (Army, Navy and Air Force) and the Joint Intelligence Bureau.

The Royal Australian Navy’s (RAN) SIGINT activities began in 1940 with two high-frequency radio interception and direction-finding stations operating near Darwin and Canberra linking with Singapore as part of Britain’s SIGINT organisation, the Government Code and Cypher School.3 In addition, a Special Intelligence Section operated in Melbourne from 1942 until the war’s end, to intercept enciphered signals traffic between the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs and its embassies and consulates overseas.

General Douglas MacArthur’s establishment of the South West Pacific Command under his direction in Brisbane in 1942 precipitated an acceleration in communications collaboration within the Alliance.

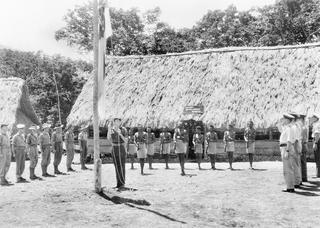

This was the catalyst for many Allied intelligence organisations, arrangements and procedures for signals intelligence, including long-range reconnaissance, coast watching and communication intercepts. In June 1942, Australia began its SIGINT activities when the Allied Intelligence Bureau (AIB) was created with the United States, the Netherlands and Britain.

The AIB was an organisation of spies and commandos assembled to solidify existing propaganda and guerrilla efforts behind enemy lines, particularly those of the Japanese. It aimed ‘to weaken the enemy by sabotage and destruction of morale and to lend aid and assistance to local effort to the same end in enemy-occupied territories.’

In practice, most of its work was in reconnaissance parties, guides, air spotting and watching coasts through Southeast Asia, including a daring 1943 raid on Singapore harbour.

One AIB foray into Timor went awry though when a group of 34 spies, mostly Portuguese and Timorese, was captured by the Japanese. The Japanese captured enough valuable information to send back to Australia wireless signals that appeared to come from the AIB party, which led to supply drops to the enemy and the capture of two more AIB groups. After a raft of misleading signals, the ‘Nippon Army’ finally sent a code on 8 August 1945 expressing thanks for ‘information received over a long period.’4

Also in 1942, the Australian Army and RAAF created the Central Bureau with the United States Army, and the Royal Australian Navy and US Navy created the Fleet Radio Unit, Melbourne (FRUMEL). The Central Bureau was attached to MacArthur’s Allied Command of the South West Pacific and worked with other US, UK and Indian SIGINT operations.

Both units had one overarching war-time mission – intercepting Japanese military communications – which became redundant at the war’s end. The key lesson learned by the Allies was that sharing information was as vital as sharing physical resources.

Five Eyes open

After the war, the Australian Government agreed in principle to the creation of a new signals intelligence organisation, the Defence Signals Bureau, but it wasn’t approved until 1947. It amalgamated the Central Bureau and the Fleet Radio Unit in Melbourne and was responsible for communications security in the armed services and government departments, supported by its counterpart organisation in the United Kingdom, the Government Communications Headquarters.

This would be an element of what became known as the Five Eyes intelligence partnership between the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada and New Zealand, although its genesis was the collaboration between British and US code-breakers in the early years of the Second World War.

Five Eyes itself wasn’t formalised; rather it morphed from one agreement to the next, beginning with what became known as the Atlantic Charter on 19 August 1941.

US President Franklin Roosevelt and UK Prime Minister Winston Churchill discussed an agreement earlier that year before signing the agreement in Newfoundland, at the US Naval Base Argentia. Churchill arrived aboard the British battleship HMS Prince of Wales and met the American president on the heavy cruiser USS Augusta. Churchill began by noting, ‘At long last, Mr. President.’ Unfortunately, a movie crew there to record the moment failed on two attempts.5

The basis of the charter was an acceptance that the United States supported Britain in the war as well as an outline of a post-war world that would largely align with western democratic values, including no territorial gains being sought by either, the right to self-determination, lowering of trade barriers, freedom of the seas and disarmament of aggressive nations.

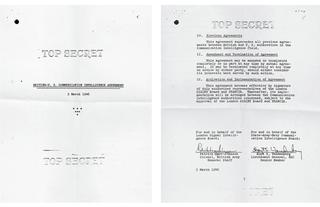

This Allied cooperation led to the informal UKUSA Agreement (initially the British-US Communication Intelligence Agreement) that was enacted officially, and secretly, in 1946. The author of a history of the US National Security Agency, James Bamford, described the UKUSA Agreement as ‘quite likely the most secret agreement ever entered into by the English-speaking world,’6 although history has unwrapped some of its operational secrets. Nevertheless, what has developed from the original UKUSA Agreement, including strong national alliances, might be considered the most consequential secret agreement ever.

Emerging from the war, Australia was not part of this major intelligence collaboration but the British wanted to organise intelligence gathering among allies, so in 1947-48, it made arrangements where particular countries had responsibility for a region. Australia became responsible for intelligence in Southeast Asia and parts of the South Pacific.

However, Australia had no likelihood of being a party to the substantive UKUSA Agreement after leaks of sensitive British and Australian data from the Soviet Embassy in Canberra. The damaging leaks were uncovered by the Venona Project, a US-UK counterintelligence project established during the Second World War to intercept Soviet intelligence and communications. The decryption of a key Soviet code led to revelations of American, Canadian, Australian and British spies reporting to the Soviet government, including Klaus Fuchs and Donald Maclean.

Unfortunately, some of the Venona intercepts, many received via the remote Australian SIGINT facilities, also revealed a Communist Party of Australia official, Walter Seddon Clayton, organised Soviet intelligence gathering in Australia. Eleven Australians were identified. Leaks to the Soviet Union from the office of HV Evatt,7 the attorney-general and minister for external affairs in the Chifley government were also uncovered.8 Typist and stenographer Frances Bernie and another Soviet agent inserted in Evatt’s office, Alfred Grundeman, who both reported to Clayton, gave the Russians access to a wealth of secret intelligence. When Soviet agent Vladimir Petrov defected to Australia in 1954, in debriefings he described Bernie and the intelligence she supplied as ‘very important.’9 Two diplomats with the Department of External Affairs were also later named as alleged KGB agents.10

The discovery of the leaks – as well as their source – damaged Australia’s security standing and Allied governments expressed their dissatisfaction at both the state of security in Australia and its unwillingness to share intelligence.

In 1949, Prime Minister Ben Chifley established a new federal security service,11 in part to show the United States (and a disappointed United Kingdom) Australia could produce and protect sensitive intelligence information, and also catch the Soviet spies. His appointment of a Director General of Security preceded the ‘Directive for the Establishment and Maintenance of a Security Service.’ In August, the new Director General, Geoffrey Reed, recommended the service be called the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO).

The service, modelled on its British counterpart, Military Intelligence 5 (MI5) had early wins, including cracking the Canberra-based Soviet spy ring and the cultivation of the Third Secretary of the Soviet Embassy, Vladimir Petrov, who was suspected of being an agent. ASIO ultimately orchestrated his high-profile defection. Such victories helped ASIO find favour with Chifley’s successor, Robert Menzies. Australia’s reputation in intelligence began to recover, continuing with the establishment of the Australian Secret Intelligence Service in 1952. Its mission remains the collection of foreign intelligence and its existence was not acknowledged by the Australian Government until 1977.

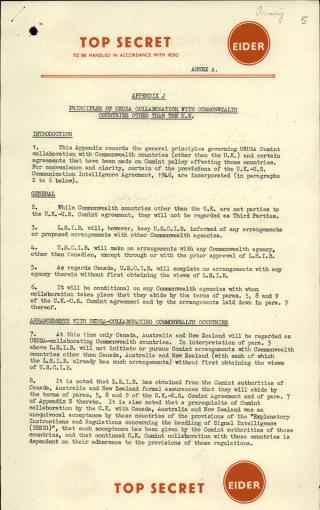

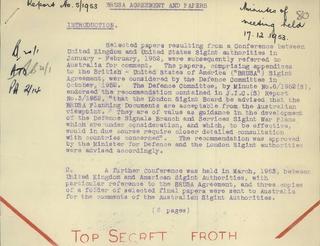

Australia was invited to join the UKUSA Agreement in 1956 (after Canada, Norway, Denmark and West Germany), initially as one of the ‘third parties’ to the agreement before the formal confirmation: ‘At this time only Canada, Australia and New Zealand will be regarded as UKUSA-collaborating Commonwealth countries.’12

The British brought Commonwealth countries into the agreement to provide it with some ballast against the weight of the United States although records suggest the Americans were wary of treating them as equals.13 Australia’s intelligence relationship with the United States accelerated during the 1950s and 60s, prompted largely by the Space Race.

Previously, Australian officials such as Minister to the United States of America, RG Casey, realised any American security pact would best be promoted by unsentimental, ‘transactional’ offers of Australian resources yet it wasn’t until the Cold War and the Space Race that Alliance partners appreciated the value of Australia’s geography (see chapter 3 for further discussion of the Space Race).

Leon E Panetta

US Secretary of Defense (2011-13), Director of the Central Intelligence Agency (2009-11), White House Chief of Staff (1994-97), US Representative from California (1977-93)

The ANZUS Treaty, the Alliance between the United States and Australia, is the cornerstone of our national security relationship.As both Secretary of Defense and Director of the CIA, I have many warm memories of all of my dear friends who were part of the critical bond between our nations.

As Director of the CIA, I witnessed how the Five Eyes organisation was at the heart of our intelligence relationship. The intelligence heads of Australia, Canada, Great Britain, New Zealand and the United States came together regularly to share sensitive information on threats, operations and technology related to protecting our security.

One of those meetings was held in Sydney where we had the opportunity to enjoy the warm hospitality of that beautiful city. I was particularly thrilled to recall how my grandfather had shared his recollections with me as a boy of the beauty of Sydney Harbour from his days on the great sailing ships in the early part of the 20th century.

But most important for me was the genuine friendship of my intelligence colleagues from Australia who never hesitated to provide vital cooperation and collaboration when necessary to protect our mutual security. Like warriors in a fox hole, we had each other’s back because we were not just allies, we were friends.

As Secretary of Defense, I enjoyed the same relationship with my counterparts when it came to defence issues. I recall fondly going to Perth with the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, General Martin Dempsey, and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton to meet with Stephen Smith, the Australian Defence Minister and others to discuss rebalancing to the Pacific and strengthening our bilateral security.

I believe it is fair to say on this 70th anniversary of our Alliance our strong bond of friendship and security is special. As we face increasing threats from our adversaries, it is reassuring to know that the Alliance between the United States and Australia remains an enduring symbol of our deep trust and faith in each other that working together, we can and will continue to protect our national security now and for the next 70 years. God bless the Alliance at 70!

Joint facilities

The catalyst for a closer intelligence relationship was the proposal for a US naval communications station at the North West Cape in Western Australia.

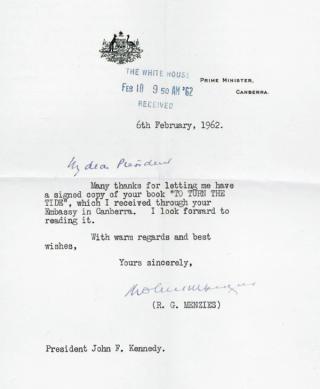

In May 1962, the Australian Government accepted the request from the Kennedy administration to establish a ‘naval communications station,’ ‘which will include a complex antenna system, high powered transmitting and receiving equipment, and administrative and supporting facilities…to provide radio communications for United States and allied ships over a wide area of the Indian Ocean and the western Pacific.’ The US government met the full cost of its construction and operation.14

The left of Australian politics was concerned about anticipated nuclear danger in, or closer to, Australia (indeed, the site’s early purpose was providing communications support for Polaris nuclear-powered submarines). President Kennedy’s cool handling of the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962 allayed some nuclear concerns yet history shows ALP leader Arthur Calwell’s handling of this issue cost his party dearly and helped minimise lasting Labor focus on the issue.

Calwell thought the site should be under joint control but he was undermined by his Federal Executive at a March 1963 meeting, which then allowed Prime Minister Menzies to call the ALP weak and anti-American. Calwell’s Labor Party lost the 1963 general election.

Australia allowed the United States access to its sovereign territory, justifying the cost of an increased risk of being a Soviet nuclear target against the benefit of being under the US nuclear umbrella and bolstering Australia’s reputation as an Alliance partner.

US Naval Communication Station North West Cape was commissioned on 16 September 1967 before being officially renamed the US Naval Communication Station Harold E. Holt in memory of the prime minister, who disappeared while swimming, three months after he opened the station. The NW Cape installation is now three sites 60 kilometres apart running the length of the narrow peninsula separating the Exmouth Gulf from the Indian Ocean. The main site hosts 13 radio towers, between 304 and 387 metres tall, that provide communications for US Navy and RAN ships and submarines in, as intended, the western Pacific and eastern Indian Oceans.15 Two other sites further south on the peninsula host high-frequency transmission and receiving facilities.

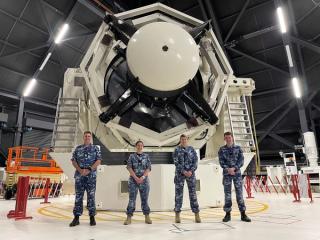

Subsequently, in 2017 a high-tech space surveillance telescope was also deployed there to track unknown objects in orbit,16 as well as military satellites for the Global Space Surveillance Network, in support of combined space operations cooperation with the United States, United Kingdom, Canada and New Zealand. Also, a new space surveillance telescope will be fully operational in 2022, to help satellite owners avoid collisions with space junk and other satellites.

The success of negotiations for NW Cape, aided by a negligible ‘peppercorn’ rent, led to agreements with the United States to establish additional satellite intelligence facilities at Pine Gap (1966) and Nurrungar (1969). Australia easily agreed to these collaborations in signals intelligence with the United States because it was lagging on defence. From the Korean War in 1952-53 to 1962-63, Australia’s defence expenditure fell from 5.1 per cent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) to 2.7 per cent.17 The United States, with a defence expenditure of 9.3 per cent of its GDP in 1962 wasn’t timid in reminding Australia it couldn’t rely on others to pay for its defence.18

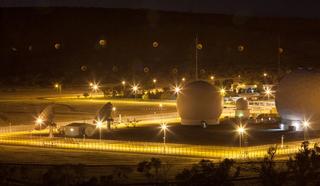

The agreement for a ‘joint defence space research facility’ at Pine Gap, a remote desert site 18 kilometres southwest of Alice Springs, established a position with two functions: receive SIGINT inputs and monitor any missile launches in the region. Pine Gap controlled US geostationary (and probably other) satellites that were originally designed to monitor signals from the Soviet Union before they later sourced signals from China, Vietnam and the Middle East.19 It was constructed and operated initially by the CIA and was critical in collecting information about Soviet ballistic missile testing, which Australian governments later used as the prime reason to justify its presence. The computer room at Pine Gap, first constructed in 1966-67, was one of the biggest computer rooms in the world at the time.20

Pine Gap was crucial to core US national security objectives: the monitoring of arms control agreements, targeting of Soviets and interception of communications across Asia.

More recently, Pine Gap supported counter-terrorism and counter-insurgency operations in Iraq and Afghanistan and has become a ground station for thermal imaging satellites in geostationary orbit. The development of powerful infrared telescopes on satellites now means they can instantly detect heat blooms of launched missiles and explosions or fires. Consequently, Pine Gap plays an indispensable role in giving the United States and its allies intelligence on missile testing and potentially warnings of any missile attack. Its management has since passed from the CIA to the US National Reconnaissance Office and Pine Gap remains arguably the most important intelligence facility outside the United States.

Another SIGINT facility, Nurrungar, near Woomera in South Australia, operated from 1969 for 30 years as ‘a joint defence space communications station.’ It controlled US Defense satellites stationed over the eastern hemisphere, most importantly providing the first warning of Iraqi Scud missile launches during the Gulf War in 1991.

In 1971, the significance of sites such as NW Cape became clearer as the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution declaring the Indian Ocean a ‘Zone of Peace,’ essentially nuclear-free.21 The Soviet Union was keen to accelerate this as it would limit the presence of the United States in the Indo-Pacific. The capability of the Australian SIGINT facilities had changed, so they would still be useful even if countries agreed to a nuclear-free zone. When President Carter later suggested the Zone of Peace be advanced, Australia disagreed, wary of its exposure and vulnerability.

Prime Minister Whitlam’s move to place RAN personnel in the NW Cape control room in 1974 was a significant advance in intelligence sharing as the Cold War deepened. It came only after an intense altercation with the Nixon administration in 1973, when he called the American autonomy at the base ‘thoroughly obnoxious.’22 Whitlam’s ire was prompted by the Middle East Alert in October 1973 when all US bases globally were put on high alert due to a fear the Soviet Union was about to intervene in the Arab-Israeli war. Whitlam noted this was done purely for ‘American domestic consumption’ to distract the media and populace from the Watergate affair.

Early the following year, Deputy Prime Minister Lance Barnard flew to Washington to seek joint control over the use of the NW Cape base, effectively demanding a veto over messages relayed from or through it.

The Nixon administration’s animus was later revealed in a private telephone conversation between Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger before Barnard’s arrival. Schlesinger looked for the right pejorative term for Whitlam before Kissinger noted, ‘He is a bastard.’

In some regards, this was a key moment in the evolution of the Alliance, as a fiesty Australian Government pressed the United States to anger. US negotiators relented to a point, granting joint operation and management of the facility with 35 Australian service personnel allowed supervisory positions and exclusive US land rights at the facility restricted to a single communications building. And an Australian flag would fly there.

It was a compromise but not enough for Whitlam. In April 1974, he was asked in Parliament about a proposal for the establishment of a joint Australian-Soviet station, ostensibly to photograph space objects. He said it wouldn’t happen and ‘the Australian government takes the attitude that there should not be foreign military bases, stations, installations in Australia. We honour agreements covering existing stations. We do not favour the extension or prolongation of any of those existing ones.’

This set US officials bustling because the Pine Gap agreement was due to terminate on 9 December 1975 and Nurrungar in December 1978. The US Ambassador to Australia Marshall Green met with Secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs Alan Renouf and told him not extending the agreements would upset the Alliance and ‘ANZUS would be called into question.’23

Broader political events, and the abrupt departure of both the Nixon and Whitlam governments, doused a potentially flammable moment in the Alliance.

Prime Minister Whitlam’s tolerance of US control of Pine Gap diminished during 1975, coinciding with a constitutional crisis that would see his government displaced.24 He strongly opposed the CIA’s control of the facility, a position some manipulated into a conspiracy theory about CIA involvement in his ousting.

Australian public opinion and politics have not always welcomed this facet of the Alliance and tolerance wilted with the revelation of the existence of previously secret intelligence organisations, ASIS and the Defence Signals Directorate, during the 1977 Hope Commission on Intelligence and Security.

In 1980, the risks of hosting US bases became starker when Australian intelligence assessments advised, ‘the USSR would rank North West Cape as an important nuclear target.’25 The former Deputy Secretary of the Australian Department of Defence, Paul Dibb, later confirmed Soviet officials issued several thinly-veiled nuclear threats against the joint facilities in various conversations with their Australian counterparts during the 1970s and 80s.26

Australia’s involvement in the FVEY network attracted more public scrutiny after revelations in a 1980 book about the activities at the Australian SIGINT ground relay stations on Australian territory staffed by US and Australian personnel.27 Nurrungar, Pine Gap and NW Cape were derided by some as American imperial outposts, with protestors picketing Pine Gap regularly during the 1980s, despite its remoteness.28

America’s various international sorties under an assertive Reagan presidency, including in Latin America and the Iran-Iraq War, did little to assuage this opposition or the new Hawke government in the early 1980s.

Hawke’s Foreign Affairs Minister Bill Hayden expressed some antipathy to the presence of permanent bases in peacetime for the US military and issued sharp responses to the 1983 US invasion of Grenada and later the Iran-Contra affair.29 This led to a clearly articulated Australian opposition to a major defence plank of the Reagan administration, the missile defence system in space, the Strategic Defence Initiative, better known as the Star Wars program.30 It would likely have required Australian assistance; nonetheless, Hayden defended the Pine Gap facility as being essential for arms control monitoring.

To allay criticism the joint facilities operated in ways contrary to Australia’s national interest, the Hawke government in 1988 announced an Australian would be appointed deputy commander at the Pine Gap and Nurrungar facilities to ensure ‘greater integration of Australian personnel in both the operation and the management of the joint facilities.’31 The United States was not wholly amenable and negotiations dragged for more than a year.

Through to the 1990s, the United States maintained more than a dozen installations in Australia for military communications, navigation and satellite tracking, including seismic stations and others providing data for the US Ocean Surveillance Information System. The Alice Springs Joint Geological and Geophysical Research Station, run by Geoscience Australia and the US Air Force, monitors nuclear explosions, including the detection and geo-location of North Korean nuclear tests in 2017. The Learmonth Solar Observatory in Western Australia, monitors solar emissions, which helps to protect communications equipment from solar interference. It is jointly operated by the Bureau of Meteorology and the US Air Force.32

Some Australian Defence Force facilities were rebadged as joint Australian and US posts, including the Australian Defence Satellite Communications Station (ADSCS) near Geraldton in Western Australia. Its status as an electronic spying outpost for the Australian Signals Directorate was enhanced for advanced US military satellite communications systems, lessening the need to use NW Cape for maritime communications and more for space initiatives. The ADSCS is believed to listen to more than 175 of the estimated 320 military satellites circling the globe, including Chinese and Russian military satellites.

Dennis Richardson AC

Secretary of the Department of Defence (2012-17), Secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (2010-12), Australian Ambassador to the United States (2005-10), Australian Director-General of Security (1996-2005)

One thing about being the Ambassador in Washington is both sides of Australian politics claim ownership of the Alliance: the ALP stress 1942; the Coalition, 1951. Both are legitimate claims, and this makes some aspects of the job relatively easy.

But there is no automaticity to an Alliance; like all relationships, they need to be constantly nurtured. This is especially so with the United States, which, like all big global powers, has a strong sense of ‘self’ and is romanced by multiple countries pursuing multiple agendas. This is the competitive environment in which even close allies operate.

Expressed sentiments such as, ‘the United States has no greater friend’ or ‘no closer ally’ are just that, sentiments – well-intentioned, but said so often to so many as to be of relatively little significance.

Substance derives overwhelmingly from hard-headed interests. Values are important but are never absolute in foreign and/or strategic policy. The very significant trade, investment and financial links between Australia and the United States add a certain breadth and depth to the relationship. People to people ties are stronger than is often appreciated and the fact Americans generally like Australians, and vice versa, is an important underpinning but does not go a long way in decision making.

Personal relationships between leaders can have a critical influence on specific issues but, if properly managed, do not make an alliance hostage to such relationships. On this front, both the United States and Australia have been sensible. And, over the decades, this has helped contribute to a degree of trust and confidence that has added ballast to the Alliance.

An alliance does not require agreement on all issues at all times. Geography and interests dictate the inevitability of differences. It is the management of those differences that count. Successive Australian and US governments have met that test, further deepening trust and confidence.

Turning up the volume

Australia wasn’t fulfilled by being merely a host or ally in intelligence matters and over time has become more assertive in using this facet of the Alliance to advance its own sovereign interests. Australia’s 1987 Defence white paper noted Australia’s self-reliance depended on ‘access to the extensive US intelligence resources.’33

By 1999, Australia was revealed to have built an intimate and broad signals intelligence relationship with the United States, when the existence of the ECHELON surveillance program was confirmed by the director of Australia’s Defence Signals Directorate, Martin Brady.34 ECHELON collected and analysed intelligence collated by the five members of the UKUSA Agreement and was formally established in 1971. Later revelations showed its military and diplomatic raison d’etre had subsequently expanded into a global system for intercepting private and commercial communications.35 Brady said Australia intercepted fax, phone and internet communications via satellites over the Indian and Pacific Oceans and forwarded filtered information to the United Kingdom and the US National Security Agency in Maryland under the ‘UKUSA alliance.’

Arguably, the outputs of the UKUSA Agreement, namely ECHELON and the broader FVEY partnership of the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada and New Zealand, has had more daily consequence to the Alliance than the ANZUS Treaty itself. Certainly, Rachel Noble, Director General of the Australian Signals Directorate, said in 2020 ‘this alliance of like-minded states is the most powerful, effective and enduring intelligence partnership the world has ever known.’36

Intelligence sharing grew stronger after 9/11 when Prime Minister John Howard invoked the ANZUS Treaty for the first time and Australia supported the United States in the War on Terror. (To read Howard’s reflections on this historic moment, see chapter 5).

In July 2004, President George W Bush sent a one-page presidential directive to the CIA and US Defense Department to upgrade intelligence cooperation and access for Australia and the United Kingdom.37 It relaxed the previous ‘NOFORN’ (to be seen by no foreign nationals) classification on American intelligence materials concerning international terrorism and joint military operations. The directive heralded a new level of intelligence cooperation, at the time allowing Australian forces in the Middle East, Iraq and Afghanistan to access direct battlespace information from the central American surveillance intelligence systems.

The United States emphasised this enhanced relationship in its 2006 Quadrennial Defense Review, the Department of Defense’s analysis of strategic objectives and military threats, saying it highly valued its ‘unique’ relationships with the United Kingdom and Australia.38

Even so, the secretive nature of intelligence means little is known of the tangible results of collaboration between the United States, Australia and its allies.

Which Australian and US agencies contribute intelligence to FVEY?

- Australian Defence Intelligence Organisation

- Australian Secret Intelligence Service (ASIS)

- Australian Signals Directorate (ASD)

- Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO)

- Australian Geospatial-Intelligence Organisation

- US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA)

- US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI)

- US National Security Agency (NSA)

- US Defense Intelligence Agency

- US National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency

Reportedly, the United States is responsible for SIGINT in Latin America, most of Asia, Russia and northern China. Australia is responsible for neighbours such as Indonesia and Malaysia, southern China, and the nations of the Pacific.39

A growing mission

National security is the primary mission of the Five Eyes network, with signals intelligence one of the better known components of the partnership. But intelligence sharing among Five Eyes partners extends into areas as diverse as ocean surveillance, covert action, human intelligence collection and counterintelligence.

A broad suite of intelligence monitoring and gathering in the post-9/11 world is required for counter-terrorism purposes, countering violent extremism, cybercrime, child exploitation, drug trafficking and even assessing foreign investment in critical infrastructure. And the range of targets has expanded from nation states to groups and individuals, either organised or informal, across the globe.

Law enforcement cooperation between Australia and the United States has generated a number of intelligence agreements including mechanisms compelling technology companies in either country to provide data relevant to investigations about serious crimes.40

In 2021, the Australian Federal Police and the US Federal Bureau of Investigation announced a three-year collaboration and ‘sting’ had infiltrated 300 criminal syndicates in 100 countries. The operation captured criminals across the globe who communicated via encrypted phones that had been designed by law enforcement in both countries. In June, more than 800 people were arrested, including more than 250 in Australia, and 3.7 tonnes of drugs and tens of millions in cash and cryptocurrencies were seized in what Europol described as the ‘biggest ever law enforcement operation against encrypted communication.’

The working relationships built in the Five Eyes network are now being used to coordinate responses to a host of newer issues. They include the economic response to the COVID-19 crisis, cybercrime, tax enforcement (the establishment of the new Joint Chiefs of Global Tax Enforcement, or J5) and, most keenly, the development of the 5G telecommunications networks. Australia was the first of the FVEY countries, ahead of the United Kingdom and the United States, to ban Chinese telco companies, namely Huawei and ZTE, from participating in their development to safeguard national security, after cyberattacks, some originating in China, hit the Australian Parliament in 2019.

Chinese hostility to the FVEY group has increased and in 2021 New Zealand’s government, under Jacinda Ardern, expressed its desire to keep FVEY’s remit to intelligence sharing only.41 However, this is unlikely given the unofficial extension of the modern FVEY group to include other nations.

China’s imposition of trade sanctions on Australia within 12 months of banning Huawei and ZTE also appears to have galvanised the FVEY partners to closer coordination.

Ultimately, since the Second World War, the Alliance has strengthened its signals intelligence relationship from one of mere convenience to now being of indispensable strategic worth.

His Excellency the Honourable Kim Beazley AC

Governor of Western Australia (2018-), Australian Ambassador to the United States (2010-16), Deputy Prime Minister of Australia (1995-96), Minister for Defence (1984-90)

The ANZUS Treaty signed on 1 September 1951 raised a question at its inception which has largely disappeared from contemporary national security debate: did it firmly commit the United States to Australia’s defence in extremity?

It was argued by some that Articles III and IV created an obligation to consult following an attack on the armed forces of a member country followed by a commitment to respond with armed force according to each party’s ‘constitutional process.’

The possibility of ambiguity was in part a product of ambiguity, particularly in the views of the American military. By 1952 they were preoccupied with events in the northern Pacific, the Middle East and Europe. They resisted putting NATO-like military muscle into a relationship in an area of strategic irrelevance in the aftermath of the Second World War. Australian policymakers were aware that a reluctant United States had felt compelled to reassure Australia in order to secure Australian support for the Japanese Peace Treaty. Not a heartfelt sense of our strategic significance.

On the right, that led to a concern for down payments by Australia via commitments when the United States found itself in conflict. On the left, fear of sovereignty depleting and possibly regular damaging entanglements.

ANZUS was a part of the San Francisco alliance system which extended US deterrence in the zone, with a hub-and-spokes model of bilateral treaties in which the United States was obviously the overwhelming hub. The debate peaked in the 1960s around Australia’s commitment to the unpopular Vietnam War. Definitely a down payment but with immediacy. Simultaneously the Australian Government was seeking comfort if quarrels with Indonesia over its confrontation with the creation of Malaysia spilt into a broader problem for Australia in Papua New Guinea. That issue receded by the mid-1960s with the failed communist coup attempt in Djakarta.

The potential impact of the war was in part mitigated by the fact that though the Labor Party eventually opposed the Australian commitment, the Party continued, in the majority, to support ANZUS. More important for the long term was that Australia, though distant from the Cold War’s major geographic fault lines, agreed to host joint facilities supporting the US strategic forces at the core of the central balance.

These are at North West Cape (communications for ballistic missile submarines), Pine Gap (critical information on Soviet capabilities) and Nurrungar (satellites providing warning of Soviet attacks).

After much debate Labor supported this commitment. Bob Hawke, then head of the trade union movement and in the 1980s prime minister, put his view this way: ‘I was a vocal opponent of the war and of United States policy in Vietnam, but my attitude towards America remained positive. To me the overriding importance of Australia’s alliance with the United States was clear. The United States, whatever its mistakes, was the bulwark of the free world…’

The joint facilities gave ANZUS strategic weight. ANZUS itself has only been exercised once thus far. That was the underpinning of Australia’s commitment to the war in Afghanistan. We invoked it in the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attack in the United States, an attack on the territory of a signatory. The joint facilities are at the heart of the Alliance. One of the paradoxes of the ANZUS agreement is that at the point of its collapse in the 1980s as a tripartite agreement over the New Zealand opposition to visits of nuclear-capable US Navy ships, it created the conditions for an intensification of the bilateral US-Australian relationship (Australia remained committed bilaterally to New Zealand as well under its rubric).

From 1986 the annual trilateral meeting was replaced by AUSMIN – the process ironically negotiated again in San Francisco. The bilateral ANZUS made it easier for the joint facilities to be brought into the heart of the annual discussions, all around the table being briefed into their functions. Simultaneously their character changed. Technological advances changed the significance of Pine Gap, in particular. It went ‘real-time.’ In the circumstances, the United States did not want the agreements time-limited. For Australia to be assured it could sustain ‘full knowledge of and consent for’ their use, Australia had to be intimately engaged. At Pine Gap and Nurrungar, Australians were to be placed on all four shifts and in command of two. Australian deputies were in charge of the facilities if the US head was absent.

Before the last AUSMIN I attended as Defence Minister, I had US Defense Secretary Dick Cheney flown into Alice Springs and on to Pine Gap by Black Hawk helicopter. I remember his head snapping around to me in surprise when the shift commander began her briefing: ‘She’s an Aussie,’ he said. At that point, the facilities entered the Australian order of battle. Further, for Australia, they became an important bargaining chip in the ANZUS relationship. That had been clear earlier in 1985’s so-called MX missile test crisis. Hawke had been able to negotiate Australia out of support for a test of the missile into our zone for fear that the facilities would become a subject of greater public controversy.

Probably in the 1980s the relationship had never been so balanced. Australia had agreed to make itself a nuclear target. Not a likely outcome but even less likely if the facilities were not present. That was genuine burden-sharing. Their value to the Americans liberated Australian foreign policy for a substantial series of initiatives, one of which was a South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone. The facilities had the advantage of making general war even less likely. They further enhanced strategic arms limitation agreements given Pine Gap’s role in verification in particular. Technological change dented Australia’s critical status when Nurrungar was dismantled though an element of redundancy in the early warning system was extended to Pine Gap. Having become used to the status the facilities brought to the Australian side in ANZUS, and their value now for Australian purposes, this development was a worry.

Partly to offset this change, from 2010 the Australian Government entered into active engagement with the United States to monitor and observe space. Two new joint facilities emerged in Western Australia.

From the mid-1970s, intensifying in the 1980s and evolving this century, the bipartisan leitmotif at the core of Australian national security settled on the notion of ‘Self-reliance within the framework of our alliances.’ ANZUS, a relationship of modest beginnings, is cemented at the heart of our concept of the requirements of national survival.