The Alliance between Australia and the United States began with the signing of the ANZUS Treaty (Australia, New Zealand, United States Security Treaty) in San Francisco in 1951 although its genesis was the many collaborations between the two countries during the 19th and 20th centuries.

A formal alliance is agreed to upon the signing of a document or the shaking of hands yet the Alliance between Australia and the United States – two nations tied by the Pacific – developed well before 1951, in many instances of collaboration and kinship after European colonisation of Australia.

The moments of shared sacrifice when Australians and Americans served together in battle, united by a common purpose, represent the clearest moments of kinship. Although collaboration between Americans and Australians has been a constant for more than a century.

For instance, the visit of the American Great White Fleet to Australia in 1908 was arguably as consequential a moment, at least with the Australian public, as was the 1918 Battle of Hamel, in which Australian General John Monash commanded American troops in a significant victory in the First World War.

Indeed, this was the first of many consequential partnerships between the two nations on global battlefields, including across the Pacific during the Second World War after Prime Minister John Curtin’s provocative 1941 message that ‘Australia looks to America.’

The Alliance is more than a fixed agreement; it has adapted to suit the times and continues to do so. These events, and others, contribute to something more meaningful than was stated in the ANZUS Treaty in 1951.

Americans were among the earliest sealers and whalers working off the Australian coast and they flocked to Australia, mostly to Victoria, during the gold rushes of the 1850s and 60s.

American diggers from the California Revolver Brigade bolstered the mining rebels at the Battle of the Eureka Stockade uprising against colonial administration of the booming goldfields at Ballarat in 1854. By the 1860s more than 3,000 Americans lived in Victoria.1

Lessons from the US Civil War would later inform the establishment of the new Australian nation.2 The circumstances of the American political upheaval coloured the new Constitution, with the word ‘indissoluble’ added to its final draft at the Federation Convention in 1898, for instance, to avoid any kind of secession leading to a civil war.3

After Australia’s Federation in 1901, the second prime minister Alfred Deakin desired a more proactive stance and independence in international affairs, including, a closer relationship with the United States, despite Britain’s displeasure.4 Australia did not appreciate Britain’s formal alliance with Japan in 1902, particularly when Britain said the ‘logical consequence’ of renouncing this alliance would be Australia and New Zealand taking naval supremacy in the China Sea, which neither was willing nor capable of doing.5

So the Pacific political landscape was primed for some mischief in 1907 when US President Theodore Roosevelt sent a fleet of 16 American battleships, all painted white in peacetime colours, to circumnavigate the globe in a deliberate display of US military capabilities overseas.

Jumping ship into the Civil War

A lesser-acknowledged unofficial ‘collaboration’ between Australia and the United States occurred in the final months of the US Civil War. In 1865, the sleek iron-framed clipper and steamer, Confederate States Ship (CSS) Shenandoah sailed into Melbourne’s Port Phillip Bay, damaged and needing supplies, under the stewardship of Lieutenant Commander James Waddell.6 The boat was a feared commercial raider, roaming the Indian Ocean burning or scuttling Union ships as the weaker Southerners diminished the Union’s naval fleet and tried to upend its economy by sabotaging trade routes. They were so successful in disrupting whalers, the cost of whale oil doubled.

Victoria reluctantly allowed Shenandoah into Melbourne on 25 January 1865, given Britain’s commitment to a neutral stance on the war and complaints by the US consul. Yet the ‘pirate ship’ became a cause célèbre, its crew feted with a dinner at the Melbourne Club and a gala ball held in the state’s own town of rebels, Ballarat.

Many men wanted to join the Shenandoah duty but Waddell didn’t want to transgress Britain’s Foreign Enlistment Act by employing British subjects, despite up to 19 of his crew deserting in Melbourne.

When Shenandoah left on 19 February and was outside the colony of Victoria’s waters, up to 45 Australians emerged from their stowaway positions and secretly enlisted to fight for the South.

Shenandoah ventured to the Bering Sea, capturing or destroying 38 ships and taking 1,053 prisoners. Conjecture has it Australians may have fired the last shot of the Civil War or even been some of the last men to die in the service of the Confederacy in June 1865 as the Shenandoah battled the Union’s Jireh Swift.

Waddell only learned of the surrender of the Confederate forces in early August, as the US Navy hunted the traitors. Waddell knew surrender in America meant probable death, so he stripped the ship of all weaponry, disguised it and fled for cover in England. The Union tracked it to Liverpool’s River Mersey, where the crew was among the last rebels to surrender, six months after the war ended.

In 1871, a Geneva tribunal assessed a US claim against Britain for damages inflicted on American shipping by British-built or assisted Confederate ships. It found Britain responsible for all acts committed by the Shenandoah after leaving port in Melbourne; Britain later paid the United States the considerable sum of US$15.5 million in reparations, dubbed the ‘Alabama Claims,’ for breaching neutrality.

The Great White Fleet

In the first years of the 20th century, Britain and Germany stoked a naval race just as Japan was also becoming a new naval force in the Pacific. Touring the US fleet would be a show of strength aimed at Japan while reinforcing US diplomatic ties with allies around the globe.

Prime Minister Deakin risked Britain’s opprobrium by inviting President Roosevelt to include Australian ports on the US Navy’s tour.7 He did so without approaching the British Foreign Office or King Edward VII’s representative, the Governor-General, knowing they would refuse.

Deakin saw the visit as a chance to build a relationship with the US Navy because Australia didn’t have a national naval force before the founding of the Royal Australian Navy in 1911, and he was wary of Britain’s commitment to the Pacific.

He also recognised strength in numbers and reflected the xenophobia of the time, saying ‘the other Great White Power of the Pacific that Britain, the United States and Australia would be united to withstand yellow aggression.’8 This was a clear message to the Australian public the detente between the British and Japanese was intolerable, particularly after Japan’s defeat of Russia in 1905. Also, some Australians were beginning to believe they had a greater kinship with the United States, which was viewed as closer to Australia in outlook, institutions, lifestyle, optimism and, ultimately, Australia’s security in the Pacific.

This optimism would not be borne out by America’s two decades of isolationism after the First World War. Nevertheless, Australia embraced the Great White Fleet as Deakin hoped and the 16 warships of the US Atlantic Battle Fleet (the largest vessel being 140 metres long and weighing 16,000 tonnes) met widespread acclaim in Sydney, Melbourne and Albany, with only a few small-scale protests by socialists, reportedly including a young future prime minister but then contributor to Socialist magazine, John Curtin.9

The Fleet Steps in Sydney’s Royal Botanic Gardens are often erroneously thought to commemorate 1788’s First Fleet. They were built in 1908 to commemorate the Great White Fleet. The ceremonial steps were ascended by Queen Elizabeth II in 1954 on her first visit to Australian soil and remain a test for joggers.

The fleet arrived in August 1908 during the middle of its 14-month tour. In Sydney, more than half a million people lined the Harbour – more than for Federation in 1901 – in what was described as a show of Anglo-Saxon solidarity.10

The Evening News captured the fervour of their arrival into Port Jackson on 20 August, writing ‘Sydney never in its history went so far afield as it did this morning…Every headland and promontory was black with a silent multitude, all gazing seaward, all expectant of the great event…Thousands of eager spectators waited patiently on every possible description of craft that ever floated on the waters of the harbour, from the lordly ocean liner to the six-foot dinghy.11 North and South Heads, Inner and Outer, George’s and Middle Heads, and Bradley’s, Quarantine, Steel, and Potts Point – every position of vantage right along both sides of the foreshores, were crowded, here in dense groups, there in more open and scattered formation.’

The American crew enjoyed festivities including the ‘Sydney Illuminations,’ during which electric lighting and searchlights lit up Circular Quay and Martin Place, as well as the battleships themselves.12

While the visiting sailors enjoyed their visit, with an estimated 150 of them unaccounted for when the fleet departed Australian shores, government business was also on their minds. The Americans assembled intelligence on the Australian ports as they toured, believing, prophetically, the day might come in a Japanese-American battle when these ports would be valuable.13

Fighting with a common purpose

American and Australian troops fought with one common purpose during the First World War. This was also the theatre in which they fought side-by-side for the first time, in an influential battle that went some way to closing the war. It was also a rare instance of US forces serving at the direction of a foreign general.

That general was Lieutenant-General Sir John Monash, who became commander of the Australian Corps, the largest corps on the Western Front in May 1918, after commanding brigades in Egypt and the Gallipoli campaign. The civil engineer was a meticulous, inventive warrior who revolutionised strategy by integrating ground forces, tanks and artillery with aircraft.

He was justifiably proud of his ascension leading the Australian Corps, writing on 31 May 1918 that his new command comprised 166,000 troops and ‘covers practically the whole Australian field army in France.’14

…for all practical purposes I am now the supreme Australian commander, and thus at long last the Australian nation has achieved its ambition of having its own Commander-in-Chief, a native-born Australian – for the first time in its history.

My command is more than two-and-a-half times the size of the British Army under the Duke of Wellington, or of the French Army under Napoleon Bonaparte, at the battle of Waterloo.

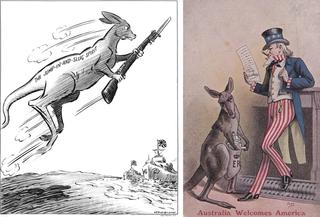

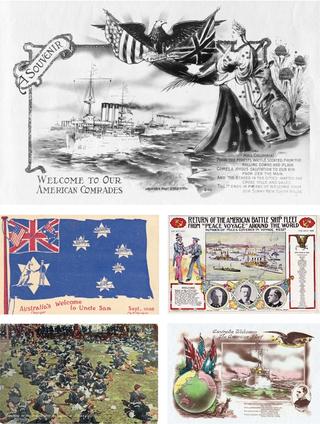

Celebrations and events surrounding the Great White Fleet’s arrival generated much ephemera and souvenirs celebrating this newfound alliance. Sharp local businesses exploited the zeitgeist with advertising postcards and posters, invariably featuring a hawk or Uncle Sam with a kangaroo or emu. They remain some of the most colourful documents of the relationship between Australia and the United States.

Battle of Hamel

In early 1918, Monash and his divisional commanders discussed a limited offensive against the Germans northeast of Villers-Bretonneux, primarily the capture of its strongest point, the village of Hamel.15

Monash aimed to straighten the front line and maintain pressure on the Germans in the first British offensive since the Battle of Cambrai in November 1917.16

He felt they could do so with the new dominant Mark V tanks, despite previous tank failures. In June, Monash submitted a plan for a sudden pre-dawn attack by four brigades, preceded by an intense artillery bombardment assisted by tanks.17

Hamel would not be the biggest battle on the Western Front but it broke the Front open.

He aimed to advance two kilometres across a six-kilometre front, taking Hamel, nearby woods and high ground beyond the village with forces including about 1,000 Americans. This was the first time in the war American Expeditionary Forces would fight under Australian command.

The plan nearly unravelled when Monash was informed on the eve of the battle that no Americans could participate. American commander General John J ‘Black Jack’ Pershing discovered US men were training with the ANZACs in preparation for battle and denied their participation, insisting that American soldiers must be led by American commanders.19

The American soldiers were so embarrassed and annoyed that some changed into Australian uniforms in protest and insisted they be able to fight with their Australian friends.

Pershing relented and allowed some, but not all, companies to take part after Monash defied him, saying the attack would proceed unless he received contrary orders from British Field Marshal Douglas Haig.

Monash wrote on 3 July, ‘although it proved a most highly inconvenient day,’ he received Australian Prime Minister Hughes and a party including two journalists (Keith Murdoch and GL Gilmour), and allowed Hughes to address the troops.20

The following day, US Independence Day, American and Australian troops fought side-by-side in an attack that began at 3.10am in smoke and fog with an attacking force of 7,500 infantry, 60 tanks and 628 heavy and field guns. Aircraft photographed and bombed enemy positions and parachuted ammunition to Australian gunners.

My Dear General,I desire to take the opportunity of tendering to you as the immediate commander, my earnest thanks for the assistance and services of the Four Companies of Infantry who participated in yesterday’s brilliant operations. The dash, gallantry and efficiency of these American troops left nothing to be desired and my Australian soldiers speak in the highest terms in praise of them. That soldiers of the United States and Australia should have thus been associated for the first time in such close co-operation on the battlefield, is an historic event of such significance that it will live forever in the annals of our respective Nations.Lieutenant General Sir John Monash, Commander Australian Corps Letter to US General Bell, Commander of the 33rd Division, 5 July 1918

Led by the Mark Vs rampaging ahead of the infantry, they wrested control of the French village near the Somme River from German control in 93 minutes and repelled a German counterattack later that night.

The Allied attack was a significant tactical and morale-boosting victory and a lesson in integrated strategy that aided the Western Front offensive.

Officially, 1,200 Australians and 176 Americans died, with Monash totalling German losses at 3,000. He also said no battle in his experience had worked so to plan; his biographer Geoffrey Serle later wrote, ‘Monash’s greatest claim to military fame may lie in the model example he gave at Hamel of the concerted use of infantry, artillery, tanks and aircraft and its subsequent application by the British Army.’21

Later, as the Allies mounted a bold offensive along the entire Western Front to push their armies to the Rhine and into Germany’s heartland in the early months of 1919, Monash would command further American forces.

In September, breaking the Hindenburg Line, which ran more than 10 kilometres deep, would be a withering undertaking, especially for battle-weary Australian troops and a physically wan Monash, who was distressed by Prime Minister Hughes’ missive to disband eight battalions (seven of them went on strike rather than disband).

Monash didn’t believe his 2nd, 3rd and 5th Divisions would be strong enough to break the three defence lines comprising the Hindenburg system, so he asked for two strong divisions to assist.23 British General Henry Rawlinson gave Monash two fresh American divisions, the 27th and 30th, to command for the initial attack on the first two lines, leaving the Australians to follow them and secure the third.

The battle was a clumsy victory after the American attack failed to seize the First Line, before the 2nd, 3rd and 5th Divisions stormed the last fortified village, Montbrehain, on 5 October. It was a momentous victory and the last action fought by Australian troops on the Western Front.

“You’ll do me Yank, but you chaps are a bit rough.”An Australian soldier to US 33rd Division soldiers after the 4 July 1918 offensive on German positions at Hamel, France

An exhausted Monash took a fortnight’s leave and on 8 November 1918 wrote ‘In course of time it will dawn upon the Australian nation that the activities of the Australian Corps were by far the biggest factor in the reversal of the fortunes of the Allies in this war, from 27 March, when the 3rd and 4th Divisions first entered the fight east of Amiens, until 6 October, when the breaching of the Hindenburg Line had been completed.’24

He added during this period he had varying forces, from his own five Australian divisions up to a total of eight divisions, including at times two Canadian divisions, two American divisions, and the British 32nd Division. At one phase he had 200,000 troops under his command.

He and his Australian troops did much to enhance the standing of Australians and their character with the American allies.

Mr Casey goes to Washington

That mutual respect wouldn’t be called on for more than 20 years, especially because in the post-war period the United States took an isolationist stance globally and Australia wrestled with its own allegiance to the ‘motherland.’ After the First World War, Prime Minister Billy Hughes eased Australia’s allegiance back to the British Empire, speaking as one voice in international affairs and expecting imperial protection.

Well into the 1930s, Australia’s relationship with Britain had its anachronisms, including the bizarre insistence for Prime Minister Lyons to send any communications to the United States through Britain. In 1936, in an apparent progression, an Australian Counsellor was appointed to the British Embassy in Washington.

Cabinet decided to establish Australian Legations in Tokyo and Washington in March 1939, before Lyons’ unfortunate death from a heart attack. In his first public announcement as the new prime minister (after Earle Page’s 20-day term), Robert Menzies confirmed the two posts.25

Australia wrestled with its allegiances before the Second World War tore apart Europe. In 1937, Prime Minister Lyons raised the notion of a Pacific Pact including Japan, the United States and European nations with Pacific interests but it gained little traction.26

Australians sensed indifference to its future, both from Britain, which was occupied with its own defence, and the United States, which didn’t see the Pacific as its concern. So, in the first years of the Second World War, Australia merely looked to the United States to support the Empire as a guarantor of its security, not supplant it.

Many Alliance historians agree possibly the most consequential movement in the US-Australian Alliance was Menzies’ appointment of the first independent diplomatic representative to Washington in 1940, appointed at the same time as Australia’s other first diplomat to Tokyo.28

“[Australia and the United States] have the same general idea of government; we attach the same supreme importance to the liberty of the individual; we have in common the conviction that the proper object of governments is to forward the happiness of ordinary men and women, and not merely of a chosen few. And we are better able to exchange our ideas and to forward our ideals by joint effort because we speak the same language and share the same literature.”Prime Minister Robert Menzies, Cablegram to Keith Officer, Australian Counsellor at British Embassy, Washington 8 January 1940

Richard (RG) Casey was a distinguished lieutenant who served in the First World War’s Gallipoli and Western Front campaigns before working in the public service and holding the federal seat of Corio for the United Australia Party for nine years. New Prime Minister Menzies saw him as a rival, so demoted his ministerial duties before appointing him the Minister to the United States of America. He was only there for two years but rarely has an appointment of political convenience had such national consequence. Casey’s lobbying efforts in those two years raised Australia’s international influence during a pivotal epoch. He began from a low base.

On arriving in Washington in 1940, Casey was told by President Roosevelt that his Cabinet decided the United States could not offer assistance to Australia if war broke out in the Pacific, which was too distant from where its strategic interests lay, or more pointedly ‘a hell of a way off.’29 Furthermore, American public opinion would not countenance it.

Initially, Casey lobbied fruitlessly for American assistance for Britain’s war effort in Europe. It wasn’t for want of trying. He wrote to Minister for External Affairs John McEwen on 8 May 1940 stating ‘Britain and Australia should do all they can to help America “express herself” in the Pacific’ to deter the Japanese.30 One way in was the possible use of Pacific islands as bases, rather than the Philippines as the United States planned. Casey added Australia ‘should be very liberal in this matter and let America use what islands she wants.’

Prime Minister Menzies then cabled President Roosevelt on 26 May 1940 asking for help for Britain while also noting Australia’s dire vulnerability. As Germany advanced, Menzies appreciated Britain couldn’t help if Australia was threatened yet he was reluctant to advocate for US assistance of Australia.

“The friendship of Australia as an integral part of the British Empire is of importance to the United States.”Prime Minister Menzies, Cable to President Roosevelt, 26 May 1940

With Britain’s aid a lost cause, Casey focused on gaining greater recognition of Australia’s significance for the United States and of the strategic value for US engagement in the southwest Pacific. The savvy former politician understood he had to sell Australia as a vital economic, political and military resource while also realising the United States wouldn’t shift policy without the imprimatur of the public.32 So he set about convincing the American public during a speaking and media campaign complementing his relentless networking of Washington DC.

Casey’s speeches had recurring themes, including the rhetorical question: why was Australia helping the Second World War efforts if it was not threatened?

Initially, he received little attention among foreign leaders; British Prime Minister Winston Churchill dismissed the notion Japan would invade Australia and beyond the immediate German threat, he was more concerned about India.33 And broadly, many foreign leaders thought any Pacific war would only be ‘a holding war’ of no strategic threat to their homelands.

That thinking moved quickly in 1941. In the first months of that year, secret British and American talks (called ABC1) in Washington made clear America’s expectation of entering the war on the Allied side.34

Of greater consequence to Australia was the commitment that defending Commonwealth interests in the Pacific would be a priority, after defending Europe. A report circulated by Australian naval attaché Henry Burrell on 7 February also said the Americans acknowledged Australia and New Zealand had to be held by the Allies.35 The implication was if Britain could not save Australia, the United States might.

By the time Menzies visited Washington in May, American attitudes thawed slightly although US briefing notes for the visit reflected the previously frosty nature of the relationship, noting relations between the two countries have been highly unsatisfactory, ‘even acrimonious’ and the United States has ‘blacklisted Australia,’ due to trade practices discriminating against it in favour of the United Kingdom.36

The Pacific Frontier

Then, on the morning of 7 December 1941, the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service attacked the hitherto neutral United States at its Pearl Harbor naval base in Honolulu and all previous Allied slights were irrelevant. Australian concerns about convincing the United States to enter the Second World War were moot.

The Japanese only planned to nobble any probable US assistance to British, Dutch or American territories or bases as it advanced across Southeast Asia - or what Menzies dubbed the ‘near North.’ But it woke a giant. Four US Navy battleships were sunk, and all eight were damaged, meaning Australia now confronted its fear, a Japanese invasion without supporting naval defence. While the Pearl Harbor attack was unexpected, a war in the Pacific had been anticipated but Australia was not prepared for it.

The United States reassured Australia it would defeat Japan but Australia didn’t appreciate the agreed Anglo-American strategy in the event of simultaneous wars in Europe and the Pacific that stipulated defeating Germany first – and immediately after Pearl Harbor, British Prime Minister Churchill raced to Washington to ensure that remained the case.

New Prime Minister John Curtin issued a formal declaration of war against Japan, something Menzies had not done with Germany, and asked for a war effort ‘to resist those who would destroy our title to Australia.’ This was the first time Australia did so as an independent nation.37

‘Men and women of Australia,’ Curtin said in a broadcast address to the nation, ‘The call is to you, for your courage; your physical and mental ability; your inflexible determination that we, as a nation of free people, shall survive. My appeal to you is in the name of Australia, for Australia is the stake in this conflict.’38

In the immediate weeks after Pearl Harbor, US General George Marshall made plans, with a junior general, Dwight D Eisenhower, for war against Japan. Eisenhower suggested they use Australia as a base of operations in the Pacific now Hawaii was disabled. Casey’s lobbying had been influential.

On 17 December, Roosevelt approved the Marshall/Eisenhower plan to use Australia as its Pacific base. If there was a moment when Australia was saved, this was it.

Weeks later, an innocent end of year message by the Australian prime minister had an impact that clearly hadn’t been ‘war-gamed’ and, arguably erroneously, resulted in Curtin being later regarded as the ‘father of the Alliance.’39

The Herald newspaper asked the prime minister for a New Year’s message to the Australian people. Its publication on 27 December was incendiary, enraging British Prime Minister Churchill, embarrassing Casey in Washington and leading President Roosevelt to say it smacked of ‘panic and disloyalty.’40

“Without any inhibitions of any kind, I make it quite clear that Australia looks to America, free of any pangs as to our traditional links or kinship with the United Kingdom.”Prime Minister John Curtin, The Herald, 27 December 1941

As Japan took the Far East, Curtin said Australia and the United States should have the primary role in deciding Pacific strategy.

More broadly, Curtin spoke of energising countries in the region for an attack as well as floating the idea of taking support from Russia and ‘working out, with the United States as a major factor, a plan of Pacific strategy, along with the British, Chinese and Dutch forces.’

Curtin and his office didn’t think much of the nuanced, logical message written by his press secretary, Don Rodgers, until the newspaper ran it on its front page, focusing on the pivot to America and making Curtin sound more diffident to Britain than he was.

Even so, Japan’s ferocious thrust into Southeast Asia, wiping British forces aside as it destroyed its crucial naval base in Singapore in February 1942, and taking other British colonies including Malaya, the Portuguese colony of East Timor, and Australian-administered Rabaul, was enough to suggest Britain could not be Australia’s saviour. And Curtin was unimpressed with Prime Minister Churchill’s anger at Australia pulling forces home from Europe and the Middle East.42

Again, the dynamism of unfolding events upended any offence.

US General George Brett left Java and resumed command of US Army Forces in Australia on 28 December 1941 in Darwin. One immediate hurdle was allowing Black American soldiers in a country still defending its racist immigration policy. The Advisory War Council, a cross-party group founded by Prime Minister Menzies and Opposition Leader Curtin in 1940, initially advised on 12 January that no Black US troops would be accepted because it would affect ‘the maintenance of the white Australia policy in the post-war settlement.’43 Prime Minister Curtin overruled the Council and allowed the troops, needing the numbers.

The United States sent reinforcements to support the embattled forces under General Douglas MacArthur in the Philippines. He’d retired from the US Army and was advising the Philippine Army before the country’s independence. But as Japan surged, that defence of the Philippines appeared doomed and losing America’s most experienced general might have been an unthinkable cost.

The fall of Singapore scuttled the American-British-Dutch-Australian Command and the British agreed the United States would assume responsibility for the southwest Pacific. On 23 February 1942, MacArthur received a message stating President Roosevelt directed him to leave ‘as quickly as possible’ and ‘proceed to Australia where you will assume command of all United States troops.’44

American troops began to congregate in Australia, concentrated in Brisbane and with headquarters at Melbourne’s Victoria Barracks.

Prime Minister Curtin was not warned General MacArthur had been ordered to Australia.45 When he arrived, Curtin was persuaded by the Americans to issue a recommendation that MacArthur be made ‘Supreme Commander South West Pacific Area,’ effectively running the Allied Pacific campaign.46 The American command believed Curtin was more interested in domestic affairs than the Japanese threat.

Almost simultaneously, and only a month before MacArthur’s arrival in Australia, Japan moved its attacks to Darwin, which was now seen as a crucial strategic port and base in the unfolding Pacific war. More than 260 enemy aircraft assaulted Darwin in a striking but militarily insignificant raid on 19 February 1942 that killed 252 Allied service personnel and civilians and destroyed most of the shipping in the harbour.

The war had come to Australia. Smaller enemy raids of Darwin and across northern Australian towns including Wyndham, Port Hedland and Derby in Western Australia, Darwin and Katherine in the Northern Territory, and Queensland’s Townsville and Mossman continued throughout 1942-43, until the final (97th) air raid on Darwin in November 1943.

Meanwhile, the politics of war unfolded down south, where MacArthur made his base at Melbourne’s Menzies Hotel. On arrival, the revered general said his presence was ‘tangible evidence’ of the ‘indescribable consanguinity of race’ between the two countries.47

This was a pivotal moment in the Alliance; the United States needed Australia’s resources and Australia was granted some strategic access – at least as much as MacArthur would grant. Curtin established a Prime Minister’s War Conference in which he met with MacArthur, moving closer to Australia’s aspiration to wield more influence with the United States during this war; he also established, with his Minister for External Affairs Dr Herbert Vere (Doc) Evatt, a Pacific War Council in Washington.

MacArthur assured Curtin in Canberra on 26 March 1942, they would ‘see this thing through together’ and ‘you take care of the rear and I will handle the front.’48 Curtin assumed MacArthur’s presence suggested the United States would support Australia. Nonetheless, when MacArthur asked whether he could, as supreme commander, deploy Australian troops, Curtin said no.49

Later, on 1 June, the morning after Japanese midget submarines penetrated Sydney Harbour for the first time (sinking a depot ship and killing 21 sailors), MacArthur privately told Curtin the United States hadn’t come to Australia through any sense of kinship or responsibility for Australian sovereignty but purely from ‘the strategical aspect of the utility of Australia as a base from which to attack and defeat the Japanese.’50 He reminded Curtin he should look to Britain, through which Australia is linked ‘by ties of blood, sentiment and allegiance to the Crown.’

Again, the dynamic movement of the war checked any politicking as Japan advanced through the Asia-Pacific.

Australian and American forces worked brilliantly together during the five-day Battle of the Coral Sea in May 1942, which was the first time Japan’s advances were quelled and the first time aircraft carriers engaged each other in battle.51 Japan aimed to fortify its position in the South Pacific by occupying New Guinea capital Port Moresby and the Solomon Islands’ Tulagi.

A joint Australian-American cruiser force opposed the offensive, supported by surprise attacks by aircraft from the US fleet carrier Yorktown and aided by intelligence from Allied codebreakers.

A month later, the Battle of Midway was the turning point of the Pacific War and, therefore, Australia’s prospects for survival. Japan planned to capture Midway Atoll and lure the US Navy into a trap but US code breakers learned of the planned attack. The Americans were well prepared for the advancing Japanese strike force and inflicted devastating damage to its aircraft carriers, sinking four and a cruiser.

Military historian John Keegan described it as ‘the most stunning and decisive blow in the history of naval warfare,’52 and General MacArthur told Prime Minister Curtin four days later on 11 June ‘the security of Australia had now been assured.’53

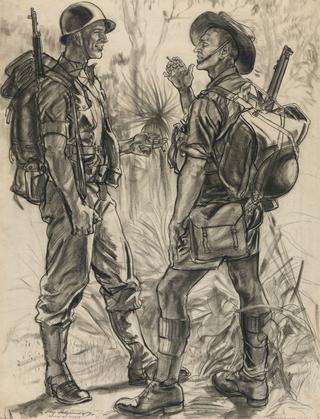

Australian and US soldiers are often referred to as ‘Diggers and Doughboys.’

The doughboy term comes from Texas, where US infantry along the Rio Grande were powdered white with adobe soil dust and hence called ‘adobes’ by mounted troops. ‘Dobies’ morphed into doughboy. The term digger derived from the gold rush in Australia, and Brits who used it to describe Aussies and New Zealanders during the First World War.

Yet Australia was still trying to hold the line in New Guinea, initially without American help. This torrid rear-guard action fending the Japanese land advance across the island would expose festering tensions between the two countries.

Reports of American soldiers dropping arms and fleeing the Japanese in New Guinea during the Battle of Buna fuelled this ill-feeling, especially when the Buna victory was later reported as an American, not Australian victory.54

MacArthur derided Australian officers there who ‘live off but not up to the name of ANZAC’55 and Prime Minister Curtin later sniped, off the record, the problems in the Battle of Milne Bay in New Guinea were ‘due to the fact that the Americans could not fight.’56 Despite the truth not being so binary, these digs splintered previous bonhomie; a pamphlet given to Americans going to fight alongside their Aussie counterparts in 1942 noted ‘the Aussies don’t fight out of a textbook. They’re resourceful, inventive soldiers, with plenty of initiative.’57

Simultaneously, Allied forces fought the Japanese on the eastern tip of New Guinea in August 1942, inflicting Japan’s first major land defeat.

Attention quickly moved to a Japanese airfield under construction at Guadalcanal in the British Solomon Islands. The arrival of Allied air forces and 19,000 US Marines led to Japan deciding it couldn’t support both fronts in New Guinea and Guadalcanal. Lieutenant General Harukichi Hyakutake focused on winning Guadalcanal and withdrawing from the daunting overland trail in New Guinea to Port Moresby, the Kokoda Track.

After the Japanese relinquished their aim to seize Port Moresby, Prime Minister Curtin congratulated MacArthur on New Year’s Day 1943 for the victory in New Guinea, which was a hard-won demonstration of ‘Comradeship in Arms.’58 And after a six-month battle, Japan retreated from Guadalcanal in February 1943.

Bands playing the Australian quasi-anthem Waltzing Matilda greeted US troops returning to Melbourne from the Guadalcanal campaign. The US Marine Corps’ revered First Division adopted the anthem and to this day its fight song remains Waltzing Matilda.

Americans in Australia

Across the three years of the Pacific War, about one million US military personnel were stationed at various locations throughout eastern Australia, from Melbourne to Townsville. The first Americans to arrive in Australia did so just two weeks after the Pearl Harbor attacks, diverted from the Phillipines to Brisbane.

In Melbourne, a sprawling American tent city, ‘Camp Pell,’59 sprang up in Royal Park and the Australian Government requisitioned the Melbourne Cricket Ground (MCG) for military purposes; between 1942-45 it hosted more than 200,000 personnel of the US Army Air Forces, the Royal Australian Air Force, and the US Marine Corps.

The MCG was known as Camp Murphy after the US Army’s Fifth Air Force occupied it and named it in honour of officer Colonel William Murphy, a senior US Army Air Forces officer killed in Java.60

While the camaraderie at the MCG was strong, with softball and American football played on the ground and the First Regiment of the First Division of the US Marine Corps hosting a US-Australian troop party in March 1943, relations between troops across the country were not always genial.

Worldly American soldiers were obviously more attractive to Australian women, particularly with their sharper uniforms and a propensity for tipping and spending (Americans had deeper pockets because the pay disparity between American and Australian soldiers was substantial).

To compensate, Australian soldiers disparaged American fighting qualities, suggesting they were all show and no substance, and they resented General MacArthur’s arrogance. Some Australians also remained stolidly racist, insisting on segregation of the estimated 100,000 Black Americans who passed through Australia.

The horrid ‘Brownout Murders,’ in which a disturbed American soldier strangled three Melbourne women did little for comradeship.

These disagreements resulted in many confrontations, some minor, some unreported, and a few inflammatory, such as the Battle of Brisbane in November 1942.The violent two-day riot was sparked by an Australian troop reaction to an over-zealous American MP arresting a drunk American private. An innocuous contretemps uncorked simmering tension fuelled by any number of previous slights and offences, leaving one Australian soldier dead, and hundreds of Australians and US servicemen injured.

Nevertheless, the social and economic impact of the American visitors was considerable and long-lasting as demand for US consumer goods grew and Australian businesses catered for this lucrative new market by embracing Coca-Cola, hamburgers and hot-dog stands. By the end of 1944, two-thirds of Australia’s imports came from the United States and American cultural trends, including fashion and cinema, had an even deeper hold on Australians than they had before the war.

A new association for better understanding

As Australia struggled to gain traction for a formal security alliance with the United States, newspaper proprietor and former war correspondent, Keith Murdoch, sensed an opportunity to lobby.

As The Herald noted in a 1952 obituary, Murdoch was ‘a spirited commentator on aspects of the Second World War, and perhaps the first to note the importance of continuing Australia’s war-time alliance with America into the post-war years.’

Prime Minister Menzies appointed him the government’s Director-General of Information in June 1940 but he soon resigned. His lobbying efforts continued, by establishing with Richard Boyer an American division of his department, which first used the term Australian American Association.

In Melbourne, Murdoch returned to his newspapers and became a spirited public voice on war matters. He founded, and was president of, the Victorian section of the Australian-American Cooperation Movement from 1941-46, which branched from the Australian American Association formed in South Australia in 1936 by two First World War veterans. It changed its name to the Australian-American Cooperation Movement as a condition of the booming Sydney branch receiving a federal grant.

Murdoch’s provocative pronouncements, both in Australia and the United States, included in 1942, his concern that the United States took Australia complacently. Yet Murdoch was a clear advocate for greater ties with the United States, seeing the United Kingdom as increasingly irrelevant and Australia’s commercial and security future more dependent on the United States.

He considered a similar, but separate, group to the Australian-based, US-orientated organisations should be formed in the United States to foster American governmental and business interest in Australia.

In July 1946, Murdoch and the President of New York’s Australian Society, Randal Heyrnanson hosted a lunch in New York to discuss a proposal with a number of prominent Americans, including Russell Leffingwell, chairman of J.P. Morgan and Co; Juan Trippe, founder of Pan American Airways; and President Roosevelt’s Postmaster General, James A Farley. The group pledged support and in 1948, the American Australian Association was incorporated as a non-profit group dedicated to fostering improved relationships between the two countries across fields of commerce, culture and politics. It has since been a regular port of call for visiting Australians since its opening meeting in 1948, during which the Australian opposition leader Robert Menzies spoke, presaging his second, more substantial term as prime minister the following year.

Post-war blues

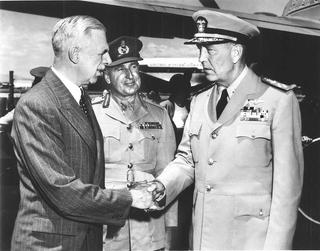

The shy and intense Curtin reluctantly agreed to stop in Washington to meet President Franklin Delano Roosevelt on his way to the Conference of Dominion Prime Ministers in May 1944, as the Allies moved towards victory. Curtin was reluctant due to his hatred of sailing, flying long distances and being out of Canberra (perhaps learning from Menzies’ ousting as prime minister in 1941).61

Roosevelt wanted to discuss ‘the future military, naval and air protection of Australia and, in a preliminary way at least, the disposition of the Japanese-owned mandated or controlled islands.’62 He also wanted to discuss the future security of the whole Asia-Pacific.

The United States was annoyed by the ANZAC agreement between New Zealand and Australia orchestrated by the controversial Australian diplomat, ‘Doc’ Evatt, which declared the sovereignty of Pacific territories should not be changed without their concurrence.63 The United States was also concerned that it might not retain control over bases it had built on British territories and Australia.

Roosevelt raised his concerns when Curtin arrived although the prime minister passed the buck, blaming Evatt for drafting the ANZAC agreement, which had arisen from ‘what may well prove to be an excess of enthusiasm.’64 After their one-hour meeting, Curtin stressed the discussions focused on ‘post-war problems, including...insurance against future aggression and the means needed to remove the fear of want and social insecurity for all mankind. The President and I found ourselves like-minded on these matters.’65

The meeting, ultimately, was a disappointment because the two ailing leaders barely talked of substantive matters, such as a framework for a new United Nations organisation. Roosevelt had moved to South Carolina to recuperate after being diagnosed in March, shortly after his 62nd birthday, with high blood pressure, atherosclerosis, coronary heart disease and congestive heart failure and was confined to four hours’ work a day.66 The reticent Curtin hardly had the disposition or political capital to meet the president on the front foot anyway. And the meeting came too late in the war. The tragedy was if Roosevelt and Curtin had met earlier, much of the animosity between the two countries about strategic priorities, lack of consultation and differing ambitions throughout the war, may have evaporated.

Nonetheless, after the Second World War, Europe was broken while the United States and Australia were two beacons of liberal democracy on either side of the Pacific, buttressed by the dual threats of a looming communist giant, China, and a humiliated Japan.

But Curtin emerged sullied by US indifference to Australia, whereas the United States emerged unmatched and about to stride confidently into the second stanza of ‘the American Century.’

At the 1946 British Commonwealth Prime Minister’s Conference, Britain told Australia and others the homeland had limited capacity and its dominions needed to do more to be self-reliant. Australia looked elsewhere.

That year, Doc Evatt proposed a tripartite joint defence board with New Zealand and the United States covering the Pacific south of the equator from Borneo to Canton Island, while also suggesting joint facilities with the United States on Manus Island and Guam.67 But the United States didn’t take up the proposal. It was more focused on Europe.

The Asia-Pacific remained a hotbed of turmoil. During 1947-49, India, Pakistan and Ceylon gained independence from Britain and the Republic of the United States of Indonesia achieved independence from the Netherlands. The People’s Republic of China was inaugurated in 1949 and Korea divided.

Yet Australia saw the United Kingdom and the United States turn a blind eye to all but Japan, which itself inspired acrimony. The United States negotiated a soft post-war agreement with Japan, hoping a pliant and armed Japan could be a useful ally against the Soviet Union but Australia wanted a more limited Japanese rearmament.

Australia realised it must forge its own path. In 1949, a conference of various Asian and Middle Eastern countries assembled, with Australia, and in the following years, many regional cooperation proposals were raised, without US support and invariably British anger. Also that year, Philippines President Quirino and Nationalist China’s Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek proposed a union of Pacific countries against communism but it didn’t progress.

Australia was stuck with the United States unwilling to enter regional security pacts in the Pacific yet also bound to inactive Commonwealth partners.

Prime Minister Ben Chifley attempted to provoke something in a radio broadcast on 15 May 1949, in which he said ‘The approach to a common scheme of defence for the Pacific area should be by agreement between Britain, Australia and New Zealand, and thereafter with the United States, and later with other nations with possessions in this area.’68

Chifley compared his proposal with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). But President Truman’s Secretary of State, Dean Acheson, was not interested in a ‘Pacific Treaty Organization’ to parallel NATO because he said any real attack on the countries would elicit a US response anyway.69 Besides, Acheson argued, the Atlantic and Pacific were very different, the latter being far larger and bordered by far more culturally and linguistically diverse nations than the North Atlantic. The United States was also wary of making arrangements with countries in Southeast Asia still under colonial rule or developing as independent states.

The United States moved gradually towards a regional pact. Acheson spoke of forming a defensive arc in the North Pacific, as the necessity for regional pacts grew.70 NZ Prime Minister Peter Fraser proposed a Pacific Pact with New Zealand, Australia, the United Kingdom, Canada, the United States, Mexico and some Central and South American countries. And while in opposition, Liberal Party politician Percy Spender suggested a pact including South Africa, India, Pakistan, Ceylon, Australia, New Zealand, Philippines, Canada and the United States.71

In 1949, governments changed in Australia and New Zealand and, again, another political appointment would have an outsized effect on the future of Australia’s foreign policy.

Percy Spender’s tempestuous career as a politician had somehow, in 1949, resulted in him being an experienced member of Robert Menzies new Liberal Party government, despite his previous disagreements with Menzies.

His first foreign policy speech in Parliament as the new External Affairs Minister consolidated his call for a defensive military arrangement between countries with a vital interest in the stability of Asia and the Pacific and the capacity to undertake military commitments, ‘particularly the United States of America, whose participation would give such a pact a substance that it would otherwise lack. Indeed, it would be rather meaningless without her.’72

A nervous Australia was repeating its message but Spender was aided by a change in global politics and US foreign policy.

Joining forces in Korea

The United States and the Soviet Union agreed to a division of the Korean Peninsula at the 38th parallel in 1945. But North Korea’s attacks on South Korea from 1946 onwards gave new impetus to a security pact during the US peace arrangements with Japan. The United States moved from a sympathetic observer of the Pacific to wanting Japan as a friend and lynchpin of the Far East in this proxy war of the United States versus China and the Soviet Union.

Australia saw an opportunity in Korea to boost its stocks with the anti-communist United States.

Spender was adamant about lifting his country’s relationship with the United States because he saw, while minister for the Army during the war, how little strategic input Australia, and other smaller nations had despite being in the heart of the conflict.73 He wasn’t alone in believing Australia deserved a place at the table given its service and sacrifice.

So when Kim Il-sung invaded South Korea and the United States needed allies – bolstered by the United Nations Security Council asking members to assist in repelling the Korean People’s Army – Spender moved. Upon hearing Britain was about to commit troops to the conflict, he quickly offered Australian troops first, wanting to be seen making an independent offer, not at the behest of Australia’s former colonial master.

In 1950, newly-elected Prime Minister Menzies was sailing on the Queen Mary to the United States, so Spender called on Acting Prime Minister Arthur Fadden to make a public statement that ‘in response to the appeal of the United Nations, the Australian Government has decided to provide ground troops for use in Korea. The nature and extent of such forces will be determined after the conclusion of discussions which the PM will have in the United States.’74

Spender later told Menzies that Britain would have ‘placed Australia and yourself as Prime Minister in an unenviable and preposterous position…I cannot believe that we, who have a much greater interest politically in our relationship with the United States in the Pacific, should be beaten to the post in the eyes of the nation and the world.’75

It was a crucial moment in Australia’s external relations, displaying autonomy and a clear allegiance to the United States over the United Kingdom.

On arriving in the United States, Prime Minister Menzies played to the crowd, telling cheering congressmen that Australian troops now in Japan would be sent to Korea ‘within as few weeks as possible.’ He concluded declaring, ‘Gentlemen, in the name of Australia, I salute you and your great people. May all you stand for and we stand for under the Providence of God be preserved for the happiness of mankind.’76

Later, Menzies opined the conflict involved ‘the fate of mankind’ and was ‘a sort of preliminary’ attack by the forces of ‘international communism.’77

Spender ensured the Australian commitment of three arms of the Australian military in South Korea with Royal Australian Navy (RAN) vessels, a Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) fighter squadron and ground forces, while also pressing for a security treaty. Australia was the second country to commit to South Korea’s defence, behind the United States.

As it happened, the Korean War transformed the post-Second World War Australian Army, which by 1950 was unable to produce a single battalion for war service, admittedly after the drastic post-war demobilisation. By the war’s end, Australia could field two infantry battalions.78

Australia moved promptly, with HMAS Bataan and HMAS Shoalhaven escorting US troopships to Pusan from Japan in the first week of July. The rapid deployment helped Australia’s nascent claims to be a Pacific power as the No. 77 Squadron flew the first ground support operations over Korea, becoming the first British Commonwealth and UN unit to see action after US forces. A mention in the US Congress noted Australia’s prompt involvement.

Australian forces fought under a UN flag in Korea in the command of US General MacArthur, Supreme Commander of United Nations forces. Under the abrasive general, UN forces took back Seoul and North Korean capital, Pyongyang.

Australia’s 3rd Battalion (3RAR) worked with the US 187th Regimental Combat Team as resistance grew while the carrier HMAS Sydney arrived in Korean waters and flew over 2,000 sorties, including ground attacks, artillery spotting, and escort missions in three months.

In a grinding war, the Royal Australian Regiment infantry battalion enhanced Australia’s reputation for ground warfare. But of the more than 17,000 Australians who served during the Korean War, 340 were killed, 1,216 wounded and a further 29 were prisoners of war.

While Australia’s haste to support the United States under the UN banner raised its global status, Prime Minister Menzies was sanguine, reportedly telling a British representative in Japan while on his way home from the United States in 1950, Korea was ‘completely useless to us strategically’ and ‘should not have been fought for.’79

Towards the treaty

In February 1951, President Truman’s special representative, John Foster Dulles, visited Tokyo, Canberra and Wellington to sell the terms of the non-aggression peace treaty with Japan and further any Pacific security arrangements ‘among the Pacific island nations (Australia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Japan, the United States, and perhaps Indonesia).’80 While Australia had been a minor player in peace talks as the Second World War ended, by 1951 Dulles felt it necessary to obtain Australia’s concurrence to a US-Japan treaty.

Canberra saw Dulles’ visit as implying the basis of a draft treaty between New Zealand, Australia and the United States, although it became apparent the United States wanted to include the strategically important Philippines.81 Meanwhile, the United Kingdom was fuming about its non-inclusion, saying its absence would be an invitation for China to take Hong Kong, Indochina and Malaya.82

Spender felt Britain was sabotaging Australia’s long, good faith efforts, yet the United Kingdom and the United States still wanted Australia to commit to playing a major role in the Middle East if there was a conflict there, as they anticipated.83 The fading Britain remained a power there and wanted three divisions of Australian forces deployed to defend the Suez Canal, the Persian Gulf and oil fields.

Spender told the United States he needed something to placate public opinion against sending troops yet again to distant climes while leaving Australia unprotected. He told US Assistant Secretary of State for UN Affairs, John Hickerson, of ‘the paramount need for (a Pacific pact) from the Australian and New Zealand point of view…how could they justify it to their people if seemingly they were leaving Australia and NZ divested of troops. One answer would be a Pacific Pact which would mean that in the event of any attack (Australia) could depend on the US coming immediately to their aid.’84

Australia would not be drawn into signing a softer treaty with Japan without the Pacific security agreement; Dulles responded by suggesting they draft a tripartite security arrangement. The United States would go it alone with the Philippines.

Menzies’ starting point was understanding the Americans’ fear of war with the Soviet Union and that NATO offered US allies significant leverage.

He wanted Australia to have a voice in the grand strategic conversations among the western democracies and felt a formal defence alliance with the United States was Australia’s best hope to access NATO strategy, despite previously dismissing ANZUS as ‘a superstructure on a foundation of jelly.’85

Spender was concerned about the consequences of change in Asia and had a dim view of the Allies’ transactional use of Australian forces in the war. Yet Spender’s only leverage with US Envoy Dulles was asking rhetorically how could Australia be expected to participate in a future war without a more concrete guarantee of its future security?

The haggling began, complicated by Spender and Menzies’ differences as well as concerns at the US State Department that Spender was more interested in being a participant in global affairs. The prime minister was willing to take the United States on trust with a presidential statement of tripartite support; Spender, perhaps burnt by the casual regard of the United Kingdom and the United States for Australian national interests during the Second World War, felt this would be inadequate and he demanded a binding treaty.86 He was a lone voice because New Zealand would also have been satisfied with a presidential declaration.

Dulles returned home with a draft tripartite security treaty to recommend to the US administration, which was formally announced by President Truman on 18 April, 10 days ahead of the re-election of the Menzies government.

In May, Spender moved to Washington as Australian Ambassador to the United States in Washington and negotiated revisions with Dulles and New Zealand Minister to the United States, Sir Carl Berendsen on Articles VII and VIII of the draft treaty. Spender’s predecessor, of sorts, RG Casey was the new Minister of Externals Affairs, and told Parliament in July the ‘heart’ of the treaty was in Article IV, wherein each party recognises ‘an armed attack in the Pacific area on any of the parties would be dangerous to its own peace and safety’ and parties would ‘act to meet the common danger in accordance with its constitutional processes.’87 Presciently, Casey added this did not specify what actions each would take.

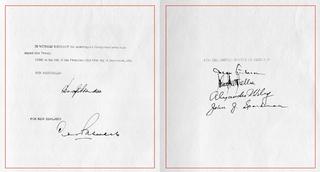

The ‘Security Treaty between Australia, New Zealand, and the United States of America’ was signed on 1 September 1951 at the Presidio in San Francisco. It is a rare treaty in that its partners are so geographically spread; it was also the first instance of Australia forming a political alliance without the involvement of Britain.

Prime Minister Menzies sent a cablegram to Spender on the day:88

Please convey to those present an expression of the great satisfaction with which we have become parties to this historic pact…The Pact is conceived in no spirit of hostility, on the contrary it embodies an enduring spirit of friendship and cooperation.

ANZUS came into effect on 29 April 1952. It wasn’t all Spender desired. He wanted more than a security guarantee, he wanted a direct link with the US chiefs of staff, which the United States denied.

A persistent Prime Minister Menzies, when meeting President Truman and Secretary of State Acheson in May with Spender, asked how Australia could participate in the formulation of global Allied strategy. Again, the United States rebuffed him before an ANZUS Council meeting in August when Acheson and Admiral Arthur Radford switched tack and thought ‘instead of starving the Australians and New Zealanders, we would give them indigestion’ with a flurry of intelligence.89

The Australians were finally sated and the Americans didn’t want the Treaty to snowball. The first ANZUS meetings, between External Affairs and State Department officers as well as a small representation from the US military, were inconsequential as Australia did not get access to Washington’s highest levels. And the Americans treated the council meetings almost as lectures, using them to outline concrete plans rather than consult with Australia and New Zealand. As Acheson later wrote, ‘For two days we went over the situation in the world, political and military, with the utmost frankness and fullness. At the end they were very happy with political liaison through the Council and military planning through the Commander in Chief Pacific.’90

The ANZUS Treaty did not immediately create the intimate military relationship Australia craved. The US Department of Defense was wary of commitments allocating US troops to fixed positions in Asia, particularly when the United Kingdom and France were still major influences on Asian security matters (through their colonies and later through the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization, or SEATO). Indeed, at the Geneva Conference as the formation of SEATO was discussed, Dulles asked External Affairs Minister Casey if that would mean ANZUS would then be redundant. Both Australia and New Zealand said no.

The reality was the Treaty had little relevance for the Americans until it wanted to establish intelligence facilities in Australia in the 1960s. But it went both ways. In the mid-1950s, when the US Pacific Fleet moved into the Taiwan Strait, Prime Minister Menzies told President Eisenhower if the United States and China were to fight over Taiwan, ANZUS would not apply and Australia would not assist.

The Offshore Islands Crisis in 1954 tested the ANZUS machinery when China began shelling an island in the Taiwan Strait. As the United States deployed its 7th Fleet to protect Taiwan, it was apparent Australia’s ANZUS obligations extended to the Taiwan Strait.

Realising the Treaty was a guarantee of safety was optimistic, Australia moved to a more pragmatic stance, quietly reminding the United States it could host defence, communications and intelligence installations.

At the ANZUS Council meeting of 1956, Casey offered the United States access to the Woomera test range, the largest land testing range in the world, which covered 13 per cent of South Australia.91 He told US Under Secretary of State, Herbert Hoover Jr (the former president’s son), ‘if at any time the US would like to make use of this range, he was sure it would be possible to make adequate arrangements.’ Hoover declined.

While the function of the ANZUS Treaty was causing angst among its partners, its form was fooling others. Australian diplomat Richard Woolcott recalled a January 1960 Australia Day reception in Moscow that attracted an unlikely guest, Soviet President Nikita Kruschev. He said, in Russian, it was a pity Australia was a member of SEATO and ANZUS because both were instruments of American imperialism.92

For years, Prime Minister Menzies struck a balance between his ‘great and powerful friends,’ the United States and the United Kingdom. However, in 1957 the balance shifted one way when he announced Australia would standardise its military equipment with the United States, rather than the United Kingdom, beginning with guided-missile destroyers for the RAN and F-111s for the RAAF, which arrived in 1968, by which time a prime reason for their acquisition, Indonesia, was no longer a threat.93

Indonesia had been a threat though, in another test for the limits of ANZUS that ultimately disappointed Australia. The Konfrontasi (Indonesia-Malaysia confrontation) was ostensibly over Indonesia’s opposition to the creation of the new state of Malaysia although underpinning it was Indonesia’s designs on Netherlands New Guinea. Australia supported the Dutch retaining control of West New Guinea but the United States remained neutral, hoping to placate Indonesia. Canberra was alarmed, anticipating potential Indonesian pressure on the Papuan border as a threat to Australia.

As the niggling between Commonwealth forces and the communist-backed Indonesia festered, the Menzies government prodded the United States in 1963 to declare whether ANZUS would be invoked if Indonesian forces attacked Malaysia. The reluctant United States didn’t want to pick sides, even as Australia pushed for clarification on whether Australian troops in North Borneo would be supported.

The United States was preoccupied with Indochina but Australian Minister for External Affairs Garfield Barwick pressed the point at the ANZUS Council. US Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs Averell Harriman said it would be best to talk privately. Later, at Sydney’s Kingsford Smith Airport, Barwick said the United States had made it clear ANZUS applied to any Australian forces operating in the Pacific.

The United States was nonplussed but when Harriman later spoke to the Menzies Cabinet and was pressed by Deputy Prime Minister John McEwan, Harriman wavered, saying ‘a reply would require a careful choice of words which he would not wish to attempt on the instant.’94

In July, Menzies discussed the matter with President John F Kennedy, saying Australia was contemplating helping defend Malaysia but was hesitant without US support.95

Kennedy asked Harriman to ‘discuss with the Australians means of consultation between Australia and the United States in advance of Australian forces being stationed in such places which would invoke the ANZUS Treaty if they were attacked.’96

Menzies committed Australian forces in Malaysia without this question resolved; weeks later Kennedy handed Australian Ambassador to the United States Howard Beale an aide-memoire on US obligations under ANZUS.97

It stated the United States would act under ANZUS only if Indonesia conducted an ‘overt attack’ on Australian forces but not for guerrilla warfare or ‘indirect aggression’ and noted any US commitment to ‘act’ under ANZUS did not necessarily imply the provision of military aid.98 The United States had wriggle room.

Barwick always pushed the relationship as Minister for External Affairs, whereas his successor, Paul Hasluck, was more like Menzies, unwilling to press the United States on specifics, in case those specifics became far more restrictive than anticipated. Menzies’ pragmatism showed when he later noted the ANZUS Alliance rested on ‘the utmost goodwill,’ not on an actual document.99

The Australians juggled the Treaty as the Asian region became an unhappy distraction for the United States in the 1960s while the Cold War intensified.

Vietnam

Australia pushed for ‘quadripartite talks’ with the United States, the United Kingdom and New Zealand for policy coordination in Southeast Asia in 1963 but America was cognisant of how it would look to have four Anglo-Saxon nations assembling to determine or influence the future of a swathe of Asia. The proposed talks did not progress.

Yet the rising spectre of communism in the Far East spearheaded by China, fortified the geopolitical ‘domino theory’ coined by President Dwight Eisenhower.100 He posited if one nation falls in a region, others will topple.

The most unstable domino was a divided Vietnam.

South Vietnam leader Ngo Dinh Diem visited Australia in 1957 and Menzies sent a ‘training team’ of 30 army advisers to the volatile region in 1962 to support the embattled leader as the communist North undermined and attacked the anti-communist South. Diem was assassinated in 1963 and America lifted its involvement in defending the South in 1965 with ground combat.

The United States approached its allies for ‘more flags’ in Vietnam and Australia had to assist, in one sense, to provide an umbrella of protection for its own servicemen then in Borneo during Indonesia’s confrontation with Malaysia.

Prime Minister Menzies committed to military action alongside the United States, despite President Lyndon B Johnson’s administration being divided on escalating its presence in Vietnam. ‘The security of Australia would be at stake if South Vietnam fell,’ Menzies noted. He didn’t approach the Vietnam conflict reluctantly, telling his Foreign Affairs and Defence Committee of Cabinet, ‘We are looking for a way in, not a way out.’101

The prime minister told Parliament on 29 April, ‘It must be seen as part of a thrust by communist China between the Indian and Pacific Oceans’ and read a letter in full from President Johnson thanking Australia for its decision.102 Arthur Calwell’s Australian Labor Party derided involving the country in a ‘civil war,’103 despite broad public support initially (Harold Holt’s landslide win in 1967 was partly attributed to the war involvement).

Menzies’ arguments aligned with the domino theory that a communist victory would destabilise Southeast Asia and be contrary to Australia’s national interests. He also believed that sending an infantry battalion would also confirm to the United States that Australia’s talk was not cheap.

Even better for Australia, to its eyes at least, the conflict locked the United States into a strategic commitment in Southeast Asia. Nonetheless, Vietnam would go on to become, arguably, the most controversial and divisive conflict in Australia’s history. The escalation of the conflict — and the burden of managing its domestic political costs — would fall to subsequent leaders, prime ministers Harold Holt and John Gorton and President Richard Nixon, rather than Menzies or LBJ.

Vietnam was America’s war though. While US troops in Vietnam peaked in excess of 500,000 at one time and 2.7 million men and women served, only 8,000 Australians served at any one time (with approximately 60,000 serving in total, 521 killed and more than 3,000 wounded).

As the decade closed, Vietnam was deteriorating and Australia’s political and public will was splintered. Australians wanted out and by the end of 1971, most Australian troops were home.

In 1969, a harried President Nixon, within months of his inauguration, sought to conclude the war and announced a position that would become known as the ‘Guam Doctrine’ (or Nixon Doctrine) but would take his country a long time to withdraw entirely.104 He said America would honour all Asian treaty agreements but in international security, the United States would ‘encourage and has a right to expect that this problem will increasingly be handled by, and the responsibility for it taken by, the Asian nations themselves.’

The United States was saying, explicitly enough, that its allies should look after their own defence although it would assist ‘nations whose survival we consider vital to our security.’ Essentially, Nixon was cutting loose South Vietnam.

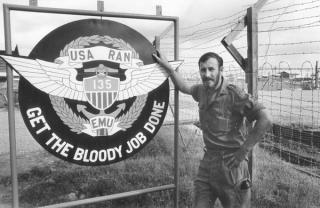

The Royal Australian Navy Helicopter Flight Vietnam (RANHFV) was specially formed to support allied forces during the Vietnam War, integrating with the US Army’s 135th Assault Helicopter Company (AHC) flying Iroquois helicopters. Its unofficial logo was the result of a 1969 competition suggested by a commanding officer to boost morale.

Stumbling through the 70s

The Vietnam War, and particularly the fall of Saigon in 1975, did no favours for the Alliance in Australian eyes. Australia’s left said the Vietnam conflict showed the Alliance to be a dangerous partnership of incompetence and arrogance while the right said it showed the United States, by extracting itself from the regional conflict, to be an unreliable ally. The United States brand was hurting and would take further blows during Nixon’s presidency.

Not that the Australian leadership was endearing itself to the United States.

Successive prime ministers Harold Holt, John Gorton and William McMahon weren’t as deferential to the White House as Menzies, despite Holt’s proclamation that he was ‘all the way with LBJ’ during a popular 1966 visit by President Lyndon B Johnson to thank Australia for its support in Vietnam.105 Nor did the United States seem perturbed about Australian defiance; when the United States established the friendly Lon Nol regime in Cambodia in 1970, it didn’t consult Australia.

John Gorton wanted an independent foreign policy before he moved aside for McMahon, who deflated the geniality of the ‘all the way’ line during his gaffe-riddled US visit in 1971. McMahon was advised it was worth asserting Australia’s pursuit of an independent foreign policy within the framework of its Alliance to downplay Holt’s previous enthusiasm.106

McMahon met Nixon but there is no Australian record of the meeting because the Australian prime minister didn’t signal bureaucrats to enter the room when planned.107 His trip was also overshadowed by Sonia McMahon’s daring dress – with full-length splits held together by rhinestones – worn to a dinner hosted by the president.

The election of Gough Whitlam’s Labor government added more volatility to the relationship with its 1972 election commitment to oppose foreign facilities on Australian soil. Then incoming Labor ministers criticised the new waves of bombing in Vietnam, calling the United States thugs. This rankled Nixon, who rated Australia with anti-war Sweden as one of the two western countries at the bottom of the White House’s Christmas card list.108

In a minor appeasement during his first major policy address, in 1973, Whitlam said the Alliance ‘represents a security guarantee in the ultimate peril.’109 The Whitlam government allowed US intelligence facilities to continue to operate on Australian soil, holding off vocal critics throughout the Labor Party.

The Alliance did not prosper during the 1970s. In 1977, President Jimmy Carter, in his first meeting with Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser, floated his support of the idea of making the Indian Ocean a de-militarised zone. This ‘flabbergasted’ the Australians who were disappointed the United States would contemplate making novel security arrangements with respect to regions as far away from the US homeland as possible, with profound implications for the security of an ally.110

Australian governments recalibrated from Gorton through to Fraser, ultimately abandoning Menzies’ ‘forward defence’ approach in favour of ‘self-reliance,’ in which defence of the Australian continent, its maritime approaches and airspace was paramount. So its three armed services became one Australian Defence Force.

By the mid-1980s, Australia’s reliance on the Alliance had moved beyond its security utility to a more independent position where the United States provided intelligence, defence technology and professional military expertise that would enable Australia to repel regional threats.

The 1980s and the threat of nuclear Armageddon – felt more keenly across Europe admittedly – gave impetus to the peace movement. The tripartite basis of the formal ANZUS Treaty would be a casualty.

In 1984, David Lange’s NZ government opposed admitting to NZ ports nuclear-armed or powered vessels, which, in short, led to the official suspension of the US-NZ leg of the ANZUS Alliance.

Australian Prime Minister Bob Hawke, as an ardent supporter of the Alliance, was unwilling to follow New Zealand and campaigned (with Foreign Minister Bill Hayden and Defence Minister Kim Beazley) to bring his party and government with him, despite internal opposition.111

Subtly, the Hawke government rebuilt the Alliance, anchored by a 1987 white paper arguing Australia should move to ‘self-reliance in an alliance context.’112

Hawke’s charisma was crucial in allowing Australia to maintain and boost the relationship, while not being a timid partner in it and managing skeptics and voices hostile to the Alliance within his own government. His Foreign Minister Gareth Evans later said this period ‘liberated Australian foreign policy.’113

When the ‘Desert Storm’ coalition coalesced in 1991 to counter Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, Prime Minister Hawke committed Australian troops overseas for the first time since Vietnam.

Australia’s primary involvement was the Naval Task Group, as part of the multi-national fleet in the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman, although more than 1,800 Defence Force personnel were also deployed in 1990-91, on attachment to US and UK ground formations. Australian medical, diving and reconnaissance teams were also deployed.

Royal Australian Navy warships would patrol the Persian Gulf for years to come, enforcing sanctions against Iraq. But these deployments to the Middle East would be dwarfed by those to follow the tragic events of 11 September 2001, opening another chapter in the long history of shared sacrifice of Australian and American defence forces.