Virtually every politically relevant, leading indicator points to the Democrats winning a majority of seats in the US House of Representatives on November 6.

Public opinion polls have long suggested an 8-9 point lead nationally for a generic Democratic House candidate over a Republican candidate; President Trump’s approval ratings, in the low 40s, are historically associated with about a 40-seat loss for Republicans, more than enough for Democrats to win a majority. Far more Democrats participated in primary elections than did Republicans, a signal of Democratic enthusiasm exceeding that of Republicans. Far more Republican incumbents retired ahead of the 2018 elections than did Democrats, again, typically indicative of electoral tides running the favour of Democrats this election cycle.

Impeachment 101: The history, process and prospect of a Trump impeachment

But Republicans have a key advantage that could help stifle the ability of Democrats to convert votes into seats in the House of Representatives. Partisan gerrymandering — the practice of drawing electoral boundaries that favour one party over another — is a key factor favouring Republicans in the 2018 midterms.

What is gerrymandering?

The term “gerrymandering” reveals its American roots, dating back at least to a districting plan enacted in Massachusetts in 1812, approved by the state’s governor, Elbridge Gerry. A map revealed one of the districts to resemble a salamander, immortalised in a cartoon in the Boston Gazette and referred to as a “Gerry-mander”.

Media reports of gerrymandering continue to dwell on the irregular shapes that gerrymandered districts sometimes exhibit. But irregular district shapes are neither necessary nor sufficient for a districting plan to be a gerrymander. The combination of (a) high rates of party loyalty among voting publics and (b) modern software for spatial data analysis and map-making means that today’s gerrymander do not require “odd shapes” or salamanders.

Partisan control of elections in the United States

Elections for Australia’s national parliament are administered by the Australian Electoral Commission, a non-partisan, professional agency, charged with maintaining the Commonwealth electoral roll, the conduct of elections and conducting electoral redistributions dividing states and territories into seats for Australia’s House of Representatives. Australian political parties make submissions to redistribution commissions, but at least in recent decades, the determination of electoral boundaries appears to be free of partisan interference and manipulation.

The situation is different in the United States, where state and local governments have responsibility for the administration of elections. The US Constitution provides that every ten years, a census shall be conducted in order to determine the apportionment of the House of Representatives seats (congressional districts, or CDs) across the 50 states, in proportion to the population of those states.1 Within any given state, the US Supreme Court insists on strict adherence to equal population in each state’s CDs, ruling out an older form of electoral manipulation known as malapportionment.2

Explainer: Getting out the vote – how US voters are mobilised

Every US state entitled to more than one CD engages in “redistricting” at the top of each decade, once the results from the decennial Census are provided. With the Census held in the “0” year (e.g., 2000, 2010, 2020, etc), the first set of elections held on the new districts are those in the “2” year (e.g., 2002, 2012, 2022, etc). Thus, in most US states, the district boundaries in place for the 2018 midterms are those drawn in 2011-2012, after the 2000 Census.

In at least 26 US states, redistricting is a political affair, an act of the state legislature, requiring majority approval from the houses of the state legislature and the governor’s assent. In 2011-12, Republicans controlled the redistricting process in 17 of these 26 states and Democrats in five states, with divided government prevailing in two of the 26 states. Earlier this year the Pennsylvania State Supreme Court overturned a Republican-drawn plan and instated a court-drawn plan. Courts or independent redistricting commissions control redistricting in 14 states.

The following table shows the frequency of different types of redistricting plans in place for the 2018 midterms, and the number of CDs under each plan. Note that 141 CDs, or about 1/3 of the Congress will be elected under plans drawn by Republican state legislatures and governors; plans enacted by courts or commissions span 16 states and 224 CDs, or about half the Congress. Democrats controlled the redistricting process in just five states spanning 42 CDs, or about 10 per cent of the Congress.

|

Control |

#States |

#CDs |

States |

|

Commission or Court |

16 |

224 |

AZ, CA, CO, CT, FL, IA, KS, MN, MS, NJ, NM, NV, NY, TX, VA, WA |

|

Democratic |

5 |

42 |

AR, IL, MA, MD, WV |

|

Divided |

2 |

11 |

KY, OR |

|

Republican |

15 |

141 |

AL, GA, IN, LA, MI, MO, NC, NE, OH, OK, PA, SC, TN, UT, WI |

|

Small states (1 or 2 CDs) |

12 |

17 |

AK, DE, HI, ID, ME, MT, ND, NH, RI, SD, VT, WY |

Partisan gerrymandering: an example

One consequence of partisan control of electoral redistricting is partisan gerrymandering, where the party in control of electoral redistricting 'packs' their opponents’ voters into a relatively small number of districts and 'crack' their opponents’ remaining voters such that they form minorities in the remaining districts. Indeed, more extreme partisan gerrymanders can see the favoured party winning a majority of seats in a jurisdiction without a winning majority of the jurisdiction’s votes.

An example appears in the following table, showing the results of election to the US House of Representatives across North Carolina’s 13 CDs.

|

District |

Dem votes |

Rep votes |

Dem % |

Winner |

Clinton % |

|

1 |

240,661 |

101,567 |

70.3 |

D |

67.5 |

|

4 |

279,380 |

130,161 |

68.2 |

D |

68.2 |

|

12 |

234,115 |

115,185 |

67.0 |

D |

68.4 |

|

13 |

156,049 |

199,443 |

43.9 |

R |

44.0 |

|

2 |

169,082 |

221,485 |

43.3 |

R |

43.6 |

|

9 |

139,041 |

193,452 |

41.8 |

R |

42.8 |

|

5 |

147,887 |

207,625 |

41.6 |

R |

39.8 |

|

8 |

133,182 |

189,863 |

41.2 |

R |

41.1 |

|

6 |

143,167 |

207,983 |

40.8 |

R |

41.4 |

|

7 |

135,905 |

211,801 |

39.1 |

R |

39.9 |

|

10 |

128,919 |

220,825 |

36.9 |

R |

36.4 |

|

11 |

129,103 |

230,405 |

35.9 |

R |

34.0 |

|

3 |

106,170 |

217,531 |

32.8 |

R |

36.9 |

|

State-wide |

2,142,661 |

2,447,326 |

46.7 |

3D/10R |

48.1 |

These data reveal several characteristics of partisan gerrymandering. First, although Democrats win 46.7 per cent of the House vote state-wide, they win only three out of 13 seats; conversely, Republicans win 10 out of 13 seats with 53.3 per cent of the vote.3

Second, it is evident that the Democratic vote has been 'packed' into three districts (1, 4 and 12), where Democrats win by margins of no less than 67-33. The remaining Democrat votes in North Carolina are dispersed throughout the 10 seats won by Republicans, with no Republican winning by less than 56-44 margins.

Third, the apparent 'packing' and 'cracking' of Democratic partisans is no accident, nor merely a peculiarity of the candidates and issues in North Carolina’s congressional races in 2016, but is also closely mirrored in votes for Hillary Clinton in the presidential election of 2016. That is, the districts have been designed with the partisanship of the voters in mind, as the Republicans who drafted this set of boundaries openly conceded.4

The North Carolina case reveals that Democrats would require a 6.1 percentage point swing to pick up a seat in that state. With a 6.1 point state-wide swing, the Democratic state-wide share of the vote across the state would rise to 52.8 per cent, yet Democrats would still only have four (31 per cent) of North Carolina’s 13 CDs. In order to win seven (a majority) of North Carolina’s 13 CDs, the state-wide swing needed is 8.4 per cent, at which point Democrats have 55.1 per cent of the statewide, two-party vote for Congress. That is, Democrats require far in excess of 50 per cent of the vote in order to win 50 per cent (or more) of North Carolina’s CDs. Conversely, Republicans can retain seven out of North Carolina’s 13 seats with as little as 44.9 per cent of the vote.

Partisan gerrymandering is widespread

North Carolina is not the only case of a pro-Republican gerrymander stifling the ability of Democrats to convert votes into seats. Similar phenomena play out in many other US states.

Florida

Consider a state like Florida, with a Republican-drawn map for its 27 House seats. Republican House candidates there won 53.1 per cent of the two-party vote for Congress, and 16 out 27 seats (59 per cent). Democrats could pick up an additional seat there with a 4.9 per cent swing, but require an 8.6 per cent swing — or 55.5 per cent of the statewide, two-party vote to win a majority of Florida’s CDs. Conversely, Republicans can retain a majority of Florida’s CDs with just under a majority of the state-wide congressional vote (44.6 per cent).

Michigan

A similar story holds in Michigan, another state with a Republican-drawn map. Republicans won eight of Michigan’s 14 seats in 2016 with 50.6 per cent of the statewide, two-party vote for Congress. Democrats could make it a 7-7 split but need a 6.9 per cent swing to do so, which would take their state-wide vote to 56.3 per cent of the two-party vote. That is, Republicans can retain a majority of Michigan’s CDs with as a little as 43.7 per cent of the state-wide vote.

Ohio

Ohio has 16 CDs, which split 12 Republican to four Democrats in 2016. A 9.2 per cent swing is needed to unseat the most marginal Republican; the most marginal Democratic seat is on 17-point margin, indicating the extent of 'packing' in the Republican-drawn boundaries. Relative to 2016, Democrats require a swing of 16.2 per cent to win a majority of Ohio’s House seats, at which point their state-wide share of the two-party vote for Congress would be 58.0 per cent. Conversely, Republicans can retain eight of Ohio’s CDs with a as little as 42 per cent of the state-wide vote.

Maryland

Maryland is perhaps the clearest case of a pro-Democratic gerrymander at present. Republicans hold just one of Maryland’s eight CDs, winning it 70-30, consistent with Republican voters there being packed. With an 8.3 per cent swing Republicans could flip the most marginal Democratic seat, but require a 15.2 per cent swing before Maryland’s eight CDs split 4D-4R. Such a swing would imply Republicans would need to win 52.2 per cent of the statewide, two-party congressional vote in order to win 50 per cent of the state’s seats, which is a mild level of partisan bias relative to the pro-Republican biases in Ohio, Michigan, Florida and North Carolina.

2018 implications

With polls suggesting Democrats will outpoll Republicans by about eight percentage points, one might reasonably conclude that Democrats will win a comfortable majority in the House. They may. But gerrymandering systematically reduces the number of marginal Republican districts, meaning that Democrats must reach quite high 'up the tree' to win the 23 or so seats they need to form a majority.

The following table lists the 30 most marginal Republican seats by their marginality based on 2016 results. Just nine seats are on margins of less than four per cent, with Democrats needing swings of six percentage points or more in order to win the seats needed for them to win a majority of the House.

Recent large swings in House elections are rarely this large. In 2010, when Democrats lost the House, they suffered a swing of 8.1 percentage points; in 2006, Democrats took the House with 5.4 point swing; in the 1994 midterms, Republicans took the House with 5.4 percentage point swing. A uniform swing of five to six points will probably be insufficient to deliver a majority to the Democrats. Much depends on where the swing occurs.

|

|

State |

District |

Incumbent |

Open seat |

Swing needed |

Trump margin |

|

1 |

CA |

49 |

Darrell Issa |

Yes |

0.3 |

-3.7 |

|

2 |

NE |

2 |

Don Bacon |

No |

0.6 |

1.1 |

|

3 |

TX |

23 |

Will Hurd |

No |

0.7 |

-1.7 |

|

4 |

MN |

2 |

Jason Lewis |

No |

0.9 |

0.6 |

|

5 |

CA |

10 |

Jeff Denham |

No |

1.7 |

-1.5 |

|

6 |

NY |

22 |

Claudia Tenney |

No |

2.7 |

7.7 |

|

7 |

VA |

10 |

Barbara Comstock |

No |

2.9 |

-5.0 |

|

8 |

CA |

25 |

Steve Knight |

No |

3.1 |

-3.3 |

|

9 |

IA |

1 |

Rod Blum |

No |

3.8 |

1.8 |

|

10 |

AL |

2 |

Martha Roby |

No |

4.1 |

16.0 |

|

11 |

CO |

6 |

Mike Coffman |

No |

4.2 |

-4.5 |

|

12 |

NY |

19 |

John Faso |

No |

4.3 |

3.4 |

|

13 |

PA |

8 |

Brian Fitzpatrick |

No |

4.5 |

0.1 |

|

14 |

ME |

2 |

Bruce Poliquin |

No |

4.8 |

5.1 |

|

15 |

FL |

27 |

Ileana Ros-Lehtinen |

Yes |

4.9 |

-9.8 |

|

16 |

FL |

18 |

Brian Mast |

No |

5.3 |

4.6 |

|

17 |

KS |

3 |

Kevin Yoder |

No |

5.4 |

-0.6 |

|

18 |

PA |

16 |

Lloyd Smucker |

No |

5.4 |

3.4 |

|

19 |

NJ |

7 |

Leonard Lance |

No |

5.5 |

-0.6 |

|

20 |

FL |

26 |

Carlos Curbelo |

No |

5.9 |

-8.1 |

|

21 |

NC |

13 |

Ted Budd |

No |

6.1 |

4.7 |

|

22 |

TX |

7 |

John Culberson |

No |

6.2 |

-0.7 |

|

23 |

UT |

4 |

Mia Love |

No |

6.2 |

3.4 |

|

24 |

MI |

11 |

David Trott |

Yes |

6.4 |

2.2 |

|

25 |

NC |

2 |

George Holding |

No |

6.7 |

4.8 |

|

26 |

CA |

21 |

David Valadao |

No |

6.7 |

-7.8 |

|

27 |

IN |

9 |

Trey Hollingsworth |

No |

6.8 |

13.4 |

|

28 |

MN |

3 |

Erik Paulsen |

No |

6.8 |

-4.7 |

|

29 |

IA |

3 |

David Young |

No |

6.9 |

1.8 |

|

30 |

AZ |

2 |

Martha McSally |

Yes |

7.0 |

-2.5 |

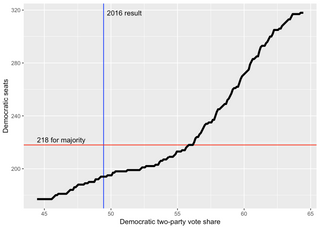

By design, partisan gerrymandering suppresses the responsiveness of elections, stifling the translation of more votes for one party into additional legislative seats for that party. The following graph shows the magnitude of the swing required — and the size of the Democratic majority with respect to votes — in order to overcome pro-Republican gerrymandering. The effect of the pro-Republican gerrymanders is to shift that 'steep' or 'responsive' component of the seats-votes curve to the right of the graph. Nationally, Democrats could require as much as 55 per cent of the two-party vote for Congress in order to win 50 per cent of the seats in the Congress.

Democrats could require as much as 55 per cent of the two-party vote for Congress in order to win 50 per cent of the seats in the Congress

Democratic seat share grows only slowly as Democratic vote share grows from 49 per cent into the low 50 per cent range. More than a few Republican incumbents enjoy comfortable margins of electoral safety, in the neighbourhood of 5 per cent or greater. On the other hand, if a Democratic wave is sufficiently large – and rises up into the high single digits, sufficient to overwhelm gerrymanders protecting Republican incumbents – relatively more Republican seats will fall.

Under a fair system, each party should have roughly the same chance of forming a majority if they win roughly half of the votes. That is manifestly not the case in contemporary American elections. The systemic, deliberate manipulation of district lines — to suppress the responsiveness of legislatures, laws and policy to public opinion — is a corruption of American democracy, and alas, could well play a key role in next Tuesday’s elections.