At a glance

- Impeachment is not the same as removing the US president. A majority vote of the House of Representatives is required to impeach a president. But impeachment is only a first step towards removal from office. After impeachment, a trial in the Senate and guilty votes from a super-majority of two-thirds of the Senate is needed to convict and remove a president from office.

- Impeachment is a political process, albeit with legal overtones. Critically, criminal acts are neither necessary nor sufficient for impeachment and conviction of a president.

- No president has been convicted and removed from office. Just two presidents have been impeached by the House. Examination of the Nixon and Clinton impeachment proceedings highlight the intensely political nature of impeachments. Nixon resigned before the House of Representatives voted on impeachment. Clinton is just one of two presidents to be impeached and tried by the Senate; the other was Andrew Johnson (1868), whose trial in the Senate concluded with an acquittal, just one vote short of the two-thirds majority required for conviction.1 Neither Clinton nor Johnson were convicted. Resignation2 or death3 remain the only ways US presidents have left office prior to electoral defeat or term limits.

- While based on only two recent cases, I tentatively venture that the following political logic structures presidential impeachment and trials. A president who thought it was likely that two-thirds of the Senate would vote for conviction would resign prior to impeachment or trial, perhaps even trading the timing and manner of their resignation for a presidential pardon from their successor, protecting them against criminal prosecution, a la Nixon. Conversely, a president confident of the result of a trial in the Senate will not resign, a la Clinton. If this logic is correct: (a) we ought to never observe a successful conviction and removal of a president from office; (b) equivalently, Senate trials of presidents — when they occur — do not result in convictions.

- Divided government was an essential element of the Nixon and Clinton impeachment proceedings. Nixon, a Republican president, faced impeachment and trial with Democratic majorities in both the House and Senate. Nixon resigned in the face of crumbling support within his own party, making impeachment and conviction all but assured. Conversely, Clinton was impeached with Republican majorities in the House of Representatives and the Senate, but with near universal opposition to impeachment among Democratic House members. No Democratic senator voted for Clinton’s conviction in the Senate.

- Public opinion remained firmly behind Clinton through 1998 as the Lewinsky scandal became public, Starr completed and published his salacious report on Clinton’s wrongdoing, and the House impeached Clinton. Clinton went into his Senate trial with approval ratings in the high 60s. In contrast, support for Nixon crumbled over 1973 as aides resigned or were fired in an attempt to insulate the president, the Senate held sensational, televised hearings into the Watergate matter and Nixon unsuccessfully attempted to end the Watergate investigation (the “Saturday Night Massacre” of October 1973). Nixon started 1973 with approval ratings in the high 60s and ended the year with the House Judiciary Committee conducting an impeachment investigation, his approval ratings in the 20s — where they would remain until his resignation in August 1974. Clinton could thus stare down impeachment and trial in the Senate. Nixon could not.

- Trump’s approval numbers lie around the 40 per cent mark, low by historical standards for a president this early in his term, but not so low that Republicans will move against him. Critically, Trump’s support among Republican partisans remains extremely high, close to Democratic levels of support for Clinton through his impeachment and Senate trial.

- Special Counsel Mueller — appointed to investigate ties between the Trump campaign and Russia — has less investigative scope and autonomy than did Kenneth Starr who served as independent counsel investigating a series of allegations against the Clintons and their associates. This suggests that the investigation into Trump — and the question about impeachment proceedings being pursued by the Congress — may be completed more expeditiously than either the Watergate investigation (1973-74) or the series of investigations by Starr (1993-1998).

- The current configuration of American political institutions — a Republican president and Republican majorities in both House and Senate — suggest it is extremely unlikely that President Trump will be impeached or convicted in the current Congress. Even if an impeachment vote could get to the floor of the House of Representatives and all of the 193 Democrats in the House voted for impeachment, at least 25 Republicans would have to vote for impeachment. Then, if all 46 Senate Democrats and two Independent senators voted for conviction, 19 Republican senators would need to support conviction for Trump to be removed from office. I think either of these scenarios extremely unlikely, based on this intensely partisan nature of impeachment votes in the Nixon and Clinton cases.

- I modestly qualify this conclusion by noting that (a) Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation continues and it would be rash to say that there is no set of circumstances that would see Republican legislators fail to support Trump; (b) midterm elections in 2018 could change the balance of power in the Congress, or put the votes for a Trump impeachment and conviction in closer reach.

I thank Dr David Smith for suggestions and comments, and Taylor Fox-Smith for research assistance with this report.

Introduction

“Will Donald Trump be impeached?” Speculation about the prospect of Trump being impeached by Congress has run ahead of careful analysis, insufficiently grounded in an understanding of the political realities underlying impeachment.

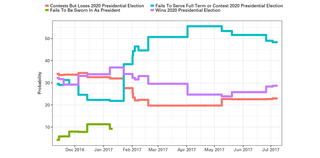

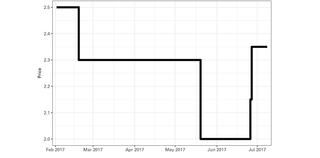

Betting markets on the prospects of Trump’s impeachment opened almost immediately after Trump became president. Since mid-February 2017, Centrebet prices have generally implied a greater than 50 per cent probability that Trump will fail to serve a full term or contest the 2020 election (Figure 1). The price on Trump being impeached in his first term fell from $2.50 to $2.00 and currently stands at $2.35 (see Figure 2); the probability of Trump being impeached implied by the current Centrebet price is 40 per cent.

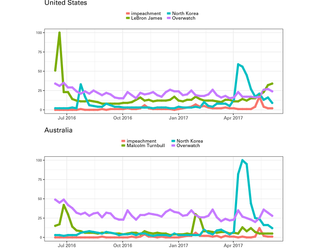

In the United States, the popularity of “impeachment” as a Google search term briefly rivalled that of pro basketballer “Le Bron James”, the video game “Overwatch”, and “North Korea” in the week of 14-20 May 2017. Australia also generates a spike of interest in impeachment in the same week, but at lower levels relative to “Overwatch” and “North Korea”. Nonetheless, the fact that a relatively technical term such as “impeachment” has generated significant search traffic is unusual (see Figure 3).

In this report I provide an examination of the constitutional, legal and political context around impeachment and removing a president. I begin by observing that impeachment is rare, with a scarce and staggered history in American history.

The first president to be impeached was Andrew Johnson in 1868; Johnson was acquited by the Senate, and it would be more than one hundred years until Nixon resigned in the face of his imminent impeachment (August 1974). Twenty-four years later, Bill Clinton was impeached but acquited by the Senate. Just two presidents have been impeached and none removed from office, testament to the rarity of impeachment and the political circumstances that have triggered recent impeachment proceedings.

After considering these factors — and my analysis of impeachment proceedings for Clinton and Nixon — I conclude that it is unlikely that Trump will be removed from office.

Impeachment, removal from office and the Constitution

Article 2, Section 4 of the Constitution of the United States provides a mechanism whereby the legislative branch can remove a president:

The President, Vice President and all civil Officers of the United States, shall be removed from Office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.

The framers of the US Constitution debated the precise wording of this provision at length. Benjamin Franklin recommended a peaceful process for removing an “obnoxious” chief executive, explicitly referencing the threat of assassination as the only other viable means for bringing the term of a president to an early end. Impeachment, Franklin argued, was thus “favourable to the executive”, preferable to a violent end to their tenure.4

The framers wanted some constraints over an executive that was otherwise designed to have considerable political and constitutional autonomy. As James Madison told the Constitutional Convention, it was:

indispensable that some provision should be made for defending the community against the incapacity, negligence or perfidy of the chief magistrate…. He might pervert his administration into a scheme of peculation or oppression. He might betray his trust to foreign powers.5

At the same time, the framers did not wish to replicate a system of parliamentary government where the chief executive served “at the pleasure” of the legislature. Impeachment and removal from office is not the same as a no-confidence motion in a Westminster system. No confidence motions can be moved at will and without any constitutional requirement that the motion be moved “with cause” or accompanied with claims of criminal behaviour by the executive. In the American system, removal from office via impeachment proceedings was designed as an extreme measure, with significant formal hurdles to clear. Hence the Constitution’s reference to “Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors”.

Impeachment is not removal from office

Article 1, Section 2 provides that the House of Representatives “shall have the sole Power of Impeachment”.

Impeachment is thus an action of the House of Representatives, requiring only a majority vote of the House. As Article 2, Section 4 makes clear, conviction after impeachment is required before removal from office.

Pathways to impeachment: the House Judiciary Committee

The Judiciary Committee of the House of Representatives has historically played a gatekeeper role in impeachment proceedings. In both the Nixon and Clinton impeachment proceedings, a majority vote of the House referred the matter to the Judiciary Committee for review or investigation. In both cases the Judiciary Committee approved articles of impeachment, referring them back to the House for consideration and adoption.

Impeachment is an action of the House of Representatives, requiring only a majority vote of the House. Conviction after impeachment is required before removal from office.

In Nixon’s case — and as I detail below — the House relied extensively on evidence collected by the staff and investigators of the Judiciary Committee, whose ranks swelled massively for the duration of the Watergate investigation,6 aided by (1) Supreme Court rulings that compelled the White House to turn over tapes of incriminating conversations between Nixon and his associated; (2) the work of special prosecutors appointed by the Justice Department; (3) an investigation by the Senate’s “Watergate Committee” that revealed the existence of the White House tapes.

In Clinton’s case, Congress relied extensively on the work of a court-appointed Independent Counsel, Kenneth Starr. Starr was not appointed by Congress, nor by the administration, but by a three-judge panel. Starr could and did bring criminal prosecutions himself. But Starr was also charged with reporting to Congress, following procedures laid out in legislation first enacted in the aftermath of Watergate. Starr was the single most important witness when the House Judiciary Committee considered impeaching Clinton; the contents of Starr’s report supplied virtually the entirety of the allegations against Clinton.

The central role of the House Judiciary Committee stems from the facts that (1) impeachment is the responsibility of the House; (2) the typical targets of impeachment are federal judges. Committees of the House are also a much more manageable vehicle for conducting investigations, hearing testimony and examining witnesses than the full House (with 435 members).

Yet, it is possible for impeachment to proceed by other means. Individual members of the House can move that the House proceed directly to consider articles of impeachment. Indeed, Democratic members of the House are circulating proposals for impeachment, citing President Trump’s decision to fire FBI Director James Comey and attempts to interfere in the investigation of Trump’s former National Security Advisor Michael Flynn as the basis for a charge of obstruction of justice.7 Typically though, the House would move to refer impeachment claims to the Judiciary Committee. Moreover, it is highly unlikely that after the precedents of the Nixon and Clinton cases that the House would move to a consideration of impeachment directly, without a referral to — and recommendations from — the Judiciary Committee.

Trial in the Senate

Article 1, Section 3 provides that

the Senate shall have the sole Power to try all Impeachments …. [but] no person shall be convicted without the Concurrence of two-thirds of the Members present.

An analogy from criminal law might be to consider impeachment by the House of Representatives as akin to indictment ahead of a trial in the Senate. The Constitution is explicit about the fact that the Senate’s consideration of an impeachment matter is a trial. The word “try” appears in Article 1, Section 2 (quoted above) and Article 1, Section 3 also provides that “When the President of the United States is tried, the Chief Justice shall preside”.

Removal from office and other penalties

Removal from office follows after a conviction (Article 2, Section 4, quoted above). But Article 1, Section 3 also provides that:

Judgment in Cases of Impeachment shall not extend further than to removal from Office, and disqualification to hold and enjoy any Office of honor, Trust or Profit under the United States: but the Party convicted shall nevertheless be liable and subject to Indictment, Trial, Judgment and Punishment, according to Law.

That is, criminal proceedings can still be brought against a former president after a conviction, highlighting that impeachment proceedings and removal from office do not necessarily involve nor resolve any question of criminal guilt or innocence. Impeachment, trial in the Senate and removal from office are designed to “maintain constitutional government”, not to punish the person in question.8 In Federalist 65, Alexander Hamilton stated that impeachment concerned:

those offences which proceed from the misconduct of public men, or, in other words, from the abuse or violation of some public trust. They are of a nature which may with peculiar propriety be denominated POLITICAL, as they relate chiefly to injuries done immediately to the society itself.

Impeachment and Senate trials of the president are the most well known and important uses of these provisions of the US Constitution. But impeachment and removal from office after Senate action is typically used with respect to federal judges. To date, the US Senate has conducted formal impeachment proceedings 19 times, resulting in seven acquittals, eight convictions, three dismissals, and one resignation with no further action; see the list on the Senate’s website.

The US Senate has conducted formal impeachment proceedings 19 times, resulting in seven acquittals, eight convictions, three dismissals, and one resignation with no further action.

Just two of these 19 actions concerned presidents: Andrew Johnson in 1868 and Bill Clinton in 1998. Neither was convicted by the Senate, meaning that no president has ever been removed from office.

I briefly examine the impeachment proceedings against Clinton and Nixon — the two recent historical case studies — highlighting the key steps towards impeachment and Senate action, emphasising the political nature of the impeachment process, contrasting legal or constitutional questions of process.

Clinton: partisanship in impeachment, trial and acquittal

Allegations that Clinton had lied under oath about his relationship with Monica Lewinsky (and had used the power of the presidency to frustrate investigations into the matter) lay at the heart of his impeachment in 1998 and trial in the Senate in early 1999. But Clinton had been under investigation for almost the entirety of his presidency, with allegations about the Whitewater matter first surfacing before Clinton had secured the Democratic presidential nomination in 1992; more than six years later the House began impeachment proceedings.

President Clinton’s personal failings — and his efforts to conceal and deny — were a critical ingredient, without which there would have been no impeachment proceedings.

In an Appendix I provide a detailed re-telling of the Whitewater matter, the appointment of Kenneth Starr as independent counsel and his investigations of various allegations of wrongdoing by the Clintons and their associates. Starr had extraordinary powers of investigation, autonomy and resources. His investigations could and did go far beyond Whitewater to the Lewinsky matter to supply grounds for Clinton’s impeachment. Clinton’s personal failings — and his efforts to conceal and deny — were a critical ingredient, without which there would have been no impeachment proceedings.

Another critical factor was that Republicans controlled both houses of Congress for most of the Clinton presidency, winning both House and Senate in the 1994 midterm elections. After almost seven years of various allegations against the Clintons, the appetite among Republicans for impeachment was irresistible. Starr’s explosive, salacious report — delivered to the Congress in September 1998 — was the trigger, supplying actionable allegations to meet pent-up political demand for action against Clinton.

Partisanship and impeachment by the House of Representatives

The House referred Starr’s report to the Judiciary Committee of the House of Representatives “for a deliberative review to determine whether sufficient grounds exist to recommend to the House that an impeachment inquiry be commenced”.9 This action was approved on 11 September 1998 by a 363-63 vote of the House, with no Republicans opposed and Democrats voting 138-63 in favour of the resolution.10 A second resolution was adopted on 8 October 1998, directing the Judiciary Committee to move to “investigate fully and completely” whether impeachment was warranted.11 The resolution was agreed to by a 258-176 vote with all Republicans and 31 Democrats voting “Aye”.12

The Lewinsky scandal and the impeachment dominated the 1998 midterm elections. Republicans lost seats at the election, suggesting that the public was not enthusiastic about the impeachment proceedings against Clinton.

The Lewinsky scandal and the impeachment dominated the 1998 midterm elections, held on 3 November 1998. Republicans lost seats at the election, suggesting that the public was not enthusiastic about the impeachment proceedings against Clinton. Newt Gingrich, Speaker of the House — leader of the “Contract with American” movement that in 1994 ended decades of Democratic control of the House of Representatives — resigned when it became clear that Republican colleagues would challenge his leadership after the poor election result.13

The lame duck session of the 105th Congress took up the impeachment question when it returned from the election recess. The House Judiciary Committee adopted four articles of impeachment. In summary, these were:

- Article I: The president provided perjurious, false and misleading testimony to the grand jury regarding the Paula Jones case and his relationship with Monica Lewinsky.

- Article II: The president provided perjurious, false and misleading testimony in the Jones case in his answers to written questions and in his deposition.

- Article III: The president obstructed justice in an effort to delay, impede, cover up and conceal the existence of evidence related to the Jones case.

- Article IV: The president misused and abused his office by making perjurious, false and misleading statements to Congress.

On Friday 11 December 1998, the Committee passed Article I 21-16; Article II passed 20-17;14 Article III passed 21-16. The Judiciary Committee took up Article IV on 12 December 1998, adopting it by a 21-16 vote.15 A motion brought by Democrats to instead censure the president was defeated 22-14. With the exception of one vote on Article II, the Judiciary Committee’s votes on adoption of the articles of impeachment were along party lines.16

The House of Representatives considered the four articles of impeachment on 18 and 19 December 1988.17 Democrats again attempted to move a censure motion against Clinton. This motion was ruled to be out of order; a dissent motion was tabled on passage of a Republican motion, 230-204, largely along party lines.18 Roll calls on the adoption of each of the four articles of impeachment then followed:

- Article I: perjury in grand jury testimony, adopted 228-206.19 Five Republicans and five Democrats broke from their parties.

- Article II: perjury in the Jones case, failed 205-229.20 28 Republicans and five Democrats broke from their parties.

- Article III: obstruction of justice with respect to evidence related to the Jones case, adopted 221-212.21 12 Republicans and five Democrats broke from their parties.

- Article IV: abuse of office, by making perjurious, false and misleading statements to Congress, failed 148-285.22 81 Republicans voted “Nay” and just one Democrat voted “Yea”.

The House then appointed 13 of its Republican members “managers”; essentially, these would be prosecutors in the Senate trial that would follow.23 The resolution appointing the House managers passed largely on party lines, 228-190, with 17 members not voting24, the final act of the 105th House of Representatives.

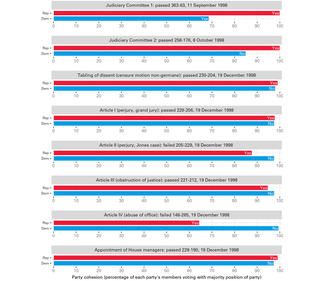

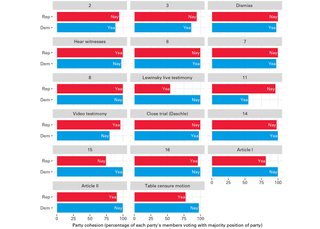

Figure 4 provides a vivid, graphical depiction of the extent to which the House impeachment votes were intensely partisan. For each of the eight impeachment related roll calls taken by the 105th House, I compute rates at which members of either party adopted the majority position adopted by their party. Lower rates (shorter bars) indicate a split among that party’s members, a departure from party-line voting. Only the votes on initially referring the Starr findings to the House Judiciary Committee and the unsuccessful vote on the Article IV have any substantial departure from party-line voting; in the former case, the departure from party-line voting comes via a split among Democrats, in the latter case, the departure comes from a split among Republicans.

Senate trial and acquittal: Democrats united and Republicans split

The House adopted two articles of impeachment with slim majorities. Given this result in the House — and the tacit lack of enthusiasm for Clinton’s impeachment and removal from office expressed in the 1998 midterm election results — few expected that the Senate trial would result in two-thirds of the Senate voting for Clinton’s conviction.

Clinton’s trial was the first order of business for the newly seated 106th Senate in January 1999. The trial began on 7 January 1999, with the formal presentation of the articles of impeachment, the House managers and the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court to the Senate.25 At this point the Senate was deemed to be sitting as a Court of Impeachment, with the Chief Justice as its presiding officer.

In accordance with the Senate’s “Rules of Procedure and Practice in the Senate when sitting on impeachment trials”, the Senate voted to issue a summons to Clinton. Preliminary motions governing the conduct of the trial were considered by the Senate. The House case was presented on 14-16 January 1999; Clinton’s defence counsel presented arguments on 19-21 January 1999. Questions from senators (submitted in writing and read by the Chief Justice) were considered on 22-23 January.

A motion to dismiss both articles of impeachment was moved by Robert Byrd (D-WV), but rejected 56-44 on 27 January.26 By the same margin, the Senate also voted to allow House managers to subpoena witnesses.27 House managers took depositions from Lewinsky, Vernon Jordon and White House aide Sidney Blumenthal.

On 4 February, a motion to have Lewinsky appear before the Senate was defeated 70-30.28 Video excerpts from witness testimony were deemed sufficient by a 62-38 vote.29 A Democratic motion to end the trial immediately — to proceed to closing arguments and votes on the Articles of Impeachment — was then defeated 56-44.30

After closing arguments and “closed door” sessions of deliberation, the Senate ended the trial on February 12, 1999. Article I (perjury) was put to the Senators with votes of either “Guilty” and “Not Guilty”; 45 Senators voted “Guilty” and 55 voted “Not Guilty”.31 Article II (obstruction of justice) produced a 50-50 split of the Senate.32 All 45 Democrats voted “Not Guilty” on both Articles. Ten Republicans joined the Democrats on Article I, five on Article II. Neither Article obtained a majority in the Senate — let alone the two-thirds super-majority specified by Article 1, section 3 of the Constitution — and Clinton was acquitted.

Finally, note that some of the senators who voted on Clinton’s impeachment trial are still in politics today. Jeff Sessions (formerly a Republican senator from Alabama) is now Trump’s attorney-general. Senators Cochran (R-MS), Collins (R-ME), Crapo (R-ID), Durbin (D-IL), Enzi (R-WY), Feinstein (D-CA), Grassley (R-IA), Hatch (R-UT), Inhofe (R-OK), Leahy (D-VT), McCain (R-AZ), McConnell (R-KY), Murkowski (R-AK), Murray (D-WA), Reed (D-RI), Roberts (R-KS), Schumer (D-NY), Shelby (R-AL) and Wyden (D-OR) — 12 Republicans and seven Democrats — remain in the Senate. If impeachment proceedings went ahead against Trump, these senators would make history as the only senators to sit in two impeachment trials. Of the 12 Republicans still serving, all except Collins (R-ME) voted to convict Clinton on both articles of impeachment; Shelby (R-AL) voted not guilty on Article I, but guilty on Article II.

Watergate and its cover-up: the case of Richard Nixon

“Watergate” has passed into the mythology of American politics, the suffix “-gate” now used to label almost any political scandal (real or alleged).33

The Watergate is a Washington DC apartment and office complex which housed the Democratic National Committee ahead of the 1972 presidential election.34 On 17 June 1972, operatives working on behalf of the Committee to Re-elect the President (CRP) posed as plumbers to infiltrate, burglarise and bug the DNC offices;35 these operatives were arrested by local police in flagrante delicto.

Watergate began as a criminal matter. But the FBI was involved in the investigation from the very beginning and almost immediately became aware of a White House connection.

Watergate thus began as a criminal matter. But the FBI was involved in the investigation from the very beginning and almost immediately became aware of a White House connection.36 An FBI informant37 reportedly leaked to Washington Post journalist Bob Woodward that the “plumbers” were connected to the White House.38

The making and discovery of a conspiracy

On 23 June 1972, Nixon and senior White House advisor H.R. Haldeman discussed how to terminate the FBI investigation. This conversation in the Oval Office (and many others) was taped and would become known as the “smoking gun” conversation, perhaps the final straw that made Nixon’s impeachment inevitable, when its contents became public two years later.

On 10 October 1972 — just weeks before the November election — it was reported39 that the FBI had established that the Watergate break-in was part of an elaborate and well-financed operation working on Nixon’s re-election. Nonetheless, Nixon handily won re-election in November 1972. Democrats retained majorities in the House of Representatives (242-192) and in the Senate (56-42-2).40

Nixon and senior White House advisor H.R. Haldeman discussed how to terminate the FBI investigation. This conversation in the Oval Office was taped and would become known as the “smoking gun” conversation, perhaps the final straw that made Nixon’s impeachment inevitable.

Guilty pleas or verdicts were returned for the Watergate burglars on 30 January 1973. Evidence produced at trial led the presiding judge John Sirica to openly posit a connection between the burglary and the White House. In March 1973, one of the burglars stated that defendants had perjured themselves at trial.41

The conspiracy and cover-up deepened throughout 1973. Nixon ordered aides to lie about connections between the White House and the burglary. Senior Nixon aides were engaged in conversations about who would “take the fall” so as to save Nixon’s presidency, while at the same time some were cooperating with prosecutors. In late April 1973, as part of a strategy to distance himself from the scandal, Nixon fired several top aides — many of whom were destined for convictions and prison terms42 — and secured the resignation of his attorney-general.

Investigations

The new attorney-general, Eliot Richardson, appointed a special prosecutor Archibald Cox to investigate the Watergate scandal in May 1973; Nixon was said to be furious with the choice of Cox, formerly Solicitor-General in the Kennedy administration.43

Unlike Starr and the investigation of Bill Clinton — and more like Mueller’s investigatory ambit — Cox did not report to Congress. In any event, congressional investigations ran concurrent with Cox’s. The Senate established a Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities (known colloquially as the “Senate Watergate Committee”) via a 77-0 vote on 7 February 1973. Reflecting that the Senate had a Democratic majority at the time, the Committee had four Democratic members (including a chair) and three Republicans. Sensationally for the time, the Committee’s public hearings were carried live on network television during the American summer of 1973 (May through August).44 During these hearings, former Nixon counsel John Dean outlined a campaign of “political espionage” being conducted out of the White House and that Nixon himself had participated in a cover-up of Watergate within days of the burglary.45

The White House tapes

During the Senate Watergate Committee hearings, it was established that the White House had a system for taping conversations. Cox asked Sirica to subpoena the tapes; Sirica did so.46 The Senate Committee also requested access to the tapes. The White House refused, asserting executive privilege, then sought to negotiate partial access to the tapes and their contents. Cox refused these offers.

In the infamous “Saturday Night Massacre” Nixon ordered Attorney-General Richardson to fire special prosecutor Cox. Richardson refused and was fired by Nixon. The same request was made of Richardson’s deputy, who resigned. Nixon’s then Acting Attorney-General Bork did fire Cox.

In the infamous “Saturday Night Massacre” (20 October 1973) Nixon ordered Attorney-General Richardson to fire Cox. Richardson refused and was fired by Nixon. The same request was made of Richardson’s deputy, who resigned. Nixon’s Solicitor-General and then Acting Attorney-General Robert Bork did fire Cox.47

Indictments against a number of former Nixon aides and advisers were brought in March 1974. Due to (a) doubts as to whether a sitting president could be criminally prosecuted and (b) an understanding that Congress’s power of impeachment was constitutionally sanctioned, Nixon was named an “unindicted co-conspirator” in the indictments brought against his former aides. This part of the indictment was sealed, but revealed in media accounts in June 1974.48

In April 1974, the Nixon administration decided to release transcripts of the tapes. The transcripts revealed an “unvarnished” Nixon, producing a fall in support for the president. In July 1974, a unanimous decision of the Supreme Court (United States vs Nixon) ruled that Nixon’s executive privilege claim was invalid and that the Special Prosecutor could access the tapes. The tapes were initially released to the public on 30 July 1974.

The House Judiciary Committee

Individual members of Congress made formal representations requesting that the Judiciary Committee commence investigations of whether Nixon had committed impeachable offenses. In 1973 the Speaker of the House referred more than a hundred such requests to the Judiciary Committee.

On 6 February 1974, the House voted 410-4 to give the Judiciary Committee broad powers to pursue an investigation against Richard Nixon.

In late 1973, an investigation by the House Judiciary Committee gathered momentum. The Judiciary Committee had 38 members, 21 Democrats and 17 Republicans, reflecting the partisan composition of the House of Representatives at the time and voted to investigate allegations against Nixon on 30 October 1973, via a party-line vote. On 6 February 1974 the House voted 410-4 to give the Judiciary Committee broad powers to pursue an investigation against the president, including the power to issue and enforce subpoenas that would “not depend upon any statutory provisions or require judicial enforcement”.49 The Committee commenced impeachments hearings on 9 May 1974, which were held in camera for two months.

By the release of the White House tapes in July 1974, the House of Representatives was well on the way towards impeaching Nixon. The House Judiciary Committee resumed televised, public hearings on 24 July 1974. Over the next week, the Committee adopted three articles of impeachment:

- Article I: adopted on 27 July 1974 by a 27-11 vote, citing obstruction of justice. The article alleged that:

On June 17, 1972, and prior thereto, agents of the Committee for the Re-election of the President committed unlawful entry of the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee… for the purpose of securing political intelligence. Subsequent thereto, Richard M. Nixon, using the powers of his high office, engaged personally and through his close subordinates and agents, in a course of conduct or plan designed to delay, impede, and obstruct the investigation of such illegal entry; to cover up, conceal and protect those responsible; and to conceal the existence and scope of other unlawful covert activities.

- Article II: adopted on 29 July 1974 by a 28-10 vote, citing abuse of power. In part, the article alleged that Nixon:

repeatedly engaged in conduct violating the constitutional rights of citizens, impairing the due and proper administration of justice and the conduct of lawful inquiries, or contravening the laws governing agencies of the executive branch and the purposed of these agencies.

- Article III: adopted on 30 July 1974 by a 21-17 vote, citing contempt of Congress. In part, the article alleged that Nixon:

…failed without lawful cause or excuse to produce papers and things as directed by duly authorized subpoenas issued by the Committee on the Judiciary of the House of Representatives … and wilfully disobeyed such subpoenas.

In addition, two proposed articles of impeachment failed to be adopted by the Committee: (1) deceiving the public over America’s bombing of Cambodia during the Vietnam conflict, defeated on a 12-26 vote;50 (2) Nixon’s failure to pay taxes,51 also defeated 12-26.

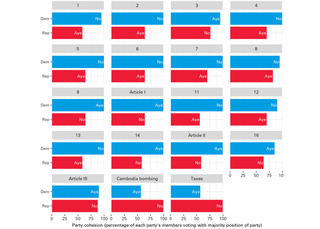

Party-line voting was a distinguishing feature of the Judiciary Committee’s formal decision-making. Figure 6 shows rates of party cohesion across 19 roll call votes taken by the Committee, including three successful votes adopting article of impeachment, the two unsuccessful proposals for additional articles of impeachment and numerous attempts at amending Article I.

Across the 19 roll calls, Democrats voted as a bloc 11 times. Republicans voted en bloc just twice, to help defeat the proposed additional articles of impeachment. Significant numbers of Republicans broke with the majority of their co-partisans on the Judiciary Committee to adopt three articles of impeachment. All Democrats voted “Aye” to adopt Article I and Article II; Republicans split 6-11 and 7-10 on these articles, respectively. Two Democrats voted against adoption of Article III (contempt of Congress); two Republicans voted to adopt it.

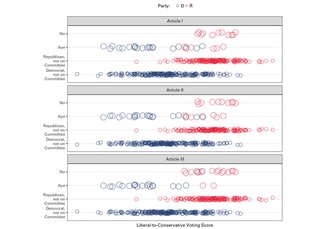

It is all but certain that a majority of the House would have adopted at least two articles of impeachment. I verify this by looking at the correspondence between the voting patterns of Judiciary Committee members relative to the voting patterns of their colleagues in the full House (see Figure 7). For each House member, I compute a liberal-to-conservative voting score, using all roll calls cast on the floor of the 93rd House prior to Nixon’s resignation.52

I impute a House member’s vote on each of the three article of impeachment by matching House members not on the Judiciary Committee to the Committee member with the closet voting score; I perform this matching without regard to party. This exercise results in the following breakdown of imputed votes in the whole House:

<table width="100%" style='border-collapse: collapse; margin-top: 1em; margin-bottom: 1em;' >

<thead>

<tr>

<th style='border-top: 2px solid grey;'></th><th colspan='2' style='font-weight: 700; border-bottom: 1px solid grey; border-top: 2px solid grey; text-align: center;'>Article I</th><th style='border-top: 2px solid grey;; border-bottom: hidden;'> </th><th colspan='2' style='font-weight: 700; border-bottom: 1px solid grey; border-top: 2px solid grey; text-align: center;'>Article II</th><th style='border-top: 2px solid grey;; border-bottom: hidden;'> </th><th colspan='2' style='font-weight: 700; border-bottom: 1px solid grey; border-top: 2px solid grey; text-align: center;'>Article III</th>

</tr>

<tr>

<th style='border-bottom: 1px solid grey;'> </th><th style='border-bottom: 1px solid grey; text-align: center;'>Aye</th><th style='border-bottom: 1px solid grey; text-align: center;'>No</th><th style='border-bottom: 1px solid grey;' colspan='1'> </th><th style='border-bottom: 1px solid grey; text-align: center;'>Aye</th><th style='border-bottom: 1px solid grey; text-align: center;'>No</th><th style='border-bottom: 1px solid grey;' colspan='1'> </th><th style='border-bottom: 1px solid grey; text-align: center;'>Aye</th><th style='border-bottom: 1px solid grey; text-align: center;'>No</th></tr></thead><tbody><tr><td style='text-align: left;'>D</td><td style='text-align: center;'>212</td><td style='text-align: center;'>34</td><td style='' colspan='1'> </td><td style='text-align: center;'>226</td><td style='text-align: center;'>20</td><td style='' colspan='1'> </td><td style='text-align: center;'>191</td><td style='text-align: center;'>55</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style='text-align: left;'>R</td><td style='text-align: center;'>75</td><td style='text-align: center;'>113</td><td style='' colspan='1'> </td><td style='text-align: center;'>95</td><td style='text-align: center;'>93</td><td style='' colspan='1'> </td><td style='text-align: center;'>46</td><td style='text-align: center;'>142</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td style='border-bottom: 2px solid grey; border-top: 1px solid #BEBEBE; font-weight: 700; text-align: left;'>All</td><td style='border-bottom: 2px solid grey; border-top: 1px solid #BEBEBE; font-weight: 700; text-align: center;'>287</td><td style='border-bottom: 2px solid grey; border-top: 1px solid #BEBEBE; font-weight: 700; text-align: center;'>147</td><td style='border-bottom: 2px solid grey; border-top: 1px solid #BEBEBE; font-weight: 700;' colspan='1'> </td><td style='border-bottom: 2px solid grey; border-top: 1px solid #BEBEBE; font-weight: 700; text-align: center;'>321</td><td style='border-bottom: 2px solid grey; border-top: 1px solid #BEBEBE; font-weight: 700; text-align: center;'>113</td><td style='border-bottom: 2px solid grey; border-top: 1px solid #BEBEBE; font-weight: 700;' colspan='1'> </td><td style='border-bottom: 2px solid grey; border-top: 1px solid #BEBEBE; font-weight: 700; text-align: center;'>237</td><td style='border-bottom: 2px solid grey; border-top: 1px solid #BEBEBE; font-weight: 700; text-align: center;'>197</td>

</tr>

</tbody>

<tr>

<td colspan='9' style='text-align: left;'></td>

</tr>

</table>

For all three articles adopted by the Judiciary Committee, this matching exercise suggests that these articles would have easily won majorities on the floor of the House. Article II (abuse of power) is predicted to have passed 321-113 with just 20 Democrats voting “No” and an almost even split among Republicans. Article III (contempt of Congress) is predicted to have passed with the smaller majority, 237 to 197. Matching House members to Committee colleagues on voting scores predicts that non-trivial numbers of Democrats would have voted against impeachment; but if party discipline or party loyalty would have determined Democratic impeachment votes, then the number of “No” votes is overestimated, recalling that no Democratic member of the Judiciary Committee voted no on Article I or Article II.

Resignation and pardon

The final blow for Nixon’s presidency came on 5 August 1974 with the release of the tape of the “smoking gun” conversation from 23 June 1972. This conversation erased any doubt as to Nixon’s direct involvement in the Watergate cover-up53 and exposed much of the previous two years of Nixon’s denials as untruthful.

Nixon’s political support among Republicans had been shaky before the release of this tape. Anywhere between six and nine of the 17 Republicans on the House Judiciary Committee had voted to adopt articles of impeachment, a sign that the full House would almost surely vote for impeachment and that a two-thirds majority for conviction in the Senate was not out of the question.

Whatever remaining support for Nixon among Congressional Republicans evaporated. Democrats had 57 seats in the Senate in mid 1974; with the support of an “independent Democrat”54 and nine of the 42 Republicans55 there would exist 67 votes for Nixon’s conviction and removal from office. Republican votes on the House Judiciary Committee to adopt articles of impeachment clearly indicated that Republican support for Nixon was not assured and certainly not monolithic.

Nixon was informed that his Senate support had collapsed and that in the event of impeachment, conviction in the Senate and removal from office was all but assured. Senator Barry Goldwater (R-AZ) — Republican presidential nominee in 1964 and distinguished party elder — is reported to have told Nixon that there were less than 15 “not guilty” votes in the Senate, far less than the 34 “not guilty” votes needed for an acquittal.56

Nixon famously announced his resignation on 8 August 1974 in a televised address. Vice President Gerald Ford become president the next day.57 Criminal charges against Nixon were still a possibility. On 8 September 1974 Ford issued a pardon of Nixon, removing the threat of criminal prosecution.

The role of public opinion

Nixon resigned in the face of crumbling support within his own party, which had made impeachment and conviction all but assured. Conversely, Clinton was impeached with Republican majorities in the House of Representatives and Senate, but with near universal opposition to impeachment among Democratic House members. No Democratic senator voted for Clinton’s conviction in the Senate.

Nixon’s fate was sealed after he lost the support of his fellow partisans in the Congress. Clinton was able to survive impeachment because his fellow Democrats continued to support him.

What role does public opinion play in accounting for the different fates of Nixon and Clinton? Nixon’s fate was sealed after he lost the support of his fellow partisans in the Congress. Clinton was able to survive impeachment because his fellow Democrats continued to support him. But why? What role did public opinion play in each case? Are there lessons to be learned that might be applicable to an assessment of public opinion with respect to Trump?

Presidental approval: Nixon, Clinton and Trump

In Figure 8 I contrast levels of presidential approval for Nixon and Clinton, as measured by Gallup surveys, highlighting the periods when Congress was actively considering impeachment for both presidents. Approval for Donald Trump is also shown (in red), time shifted so as to align with the corresponding point of the Nixon and Clinton presidential terms, respectively.

The collapse in Nixon’s standing with the American public over calendar year 1973 is stark and a critical precursor to the House Judiciary Committee pursuing Nixon’s impeachment. At the time of Nixon’s re-inauguration in January 1973, his approval ratings stood at 66 per cent, the highest approval rating Gallup recorded for Nixon. Recall that throughout 1973 Nixon aides were resigning or being fired, the Senate “Watergate Committee” held sensational, televised hearings in May, and Nixon attempted to shut down the Watergate investigation in the “Saturday Night Massacre” (20 October). By July 1973, Nixon’s approval ratings had dropped below 40 per cent and continued to fall below 30 per cent by October. Nixon’s approval ratings remained mired in the 20-30 per cent range as the House Judiciary Committee conducted its investigation. Nixon’s last ten months in office saw him with approval ratings never above the high 20s, a testament to his dwindling political capital and a strong indicator that conviction and removal from office would be the result of impeachment.

Clinton could be confident of staring down impeachment by the Republican-controlled House of Representatives, secure in the knowledge that with approval ratings in the high 60s Democratic Senators would not vote to convict.

In contrast, Bill Clinton’s approval ratings had been gradually increasing from the summer of 1994 onwards. By early 1998, Clinton was recording 60 per cent approval ratings in Gallup polls. The Gallup poll conducted immediately after the Lewinsky scandal — and Clinton’s famous televised denial — showed a nine point increase in Clinton’s approval ratings. Throughout 1998, even as Starr’s investigation reached its crescendo — questioning Lewinsky in July and August of 1998 — Clinton’s approval ratings remained at or above 60 per cent. The delivery and publication of Starr’s report and Clinton’s impeachment by the House of Representatives did nothing to dent his approval ratings. A Gallup poll fielded as the House impeached Clinton found his approval ratings to be 73 per cent, a ten point increase on the preceding Gallup poll. Throughout Clinton’s trial in the Senate his approval ratings stayed above 65 per cent. By 2000, Clinton’s approval rating was around 60 per cent; a post-election bump saw the outgoing, two-term president leave office with approval ratings in high 60s.

The contrast with Nixon’s case could not be more stark. Clinton could be confident of staring down impeachment by the Republican-controlled House of Representatives, secure in the knowledge that with approval ratings in the high 60s — and sometimes higher — Democratic Senators would not vote to convict. Indeed, no Democratic senator voted for Clinton’s conviction.

In-party versus out-party support

A critical element of political support for a president is the distinction between approval among partisans of the president’s party, among independents and among partisan of the “out-party”. Few presidents have high levels of approval from out-party partisans, a tendency that has become more pronounced over time as levels of partisan and ideological polarisation have risen in the United States. The average difference in presidential approval ratings between Democrats and Republicans has increased from a range of 26 to 40 points under Eisenhower to Carter, to 52 points under Reagan, 55 points under Clinton, 60 points under George W. Bush and 71 points under Obama. The first months of Trump’s presidency have produced a 77 point average inter-party difference in approval ratings for Trump, an unprecedented level of partisan polarisation within presidential approval.58

Republican support for Trump has cooled somewhat, but continues to be overwhelmingly positive. This data strongly suggests that Trump will not face an impeachment threat in the current Congress.

Of critical importance in thinking through the political logic of impeachment is the standing of the president with partisans of the president’s party. Recall that while a majority vote of the House is required to impeach a president, conviction and removal from office requires a two-thirds vote of the Senate. Even if the out party has a simple majority in both House and Senate (as was the case for Nixon and Clinton), removal from office can only result when substantial numbers of legislators from the president’s party are of the same view. In turn, this suggests that polling data tapping the president’s approval among partisans of the president’s party are a critical barometer of the chances that a president will be impeached or removed from office.

In Figure 9 I present levels of approval for Nixon, Clinton and Trump, by party identification. The precipitous slide in Nixon’s approval ratings through 1973 occurs across all partisan groups, but is especially pronounced among Independents. Republicans begin 1973 with approval ratings of Nixon of around 90 per cent, as Nixon was re-inaugurated after the 1972 election. By the time of House Judiciary Committee investigation in late 1973, Nixon’s in-party approval rating had dropped to below 60 per cent, reaching 50 per cent by the time the Committee adopted articles of impeachment against Nixon. This made Nixon especially vulnerable once the “smoking gun” conversation was made public, with support among Republicans insufficient to stave off a two-thirds vote for conviction had impeachment proceeded to the Senate.

Clinton never received high levels of support from Republicans, averaging a 27 per cent approval rating from Republicans over the eight years of his presidency. Importantly, as the Republican-controlled House moved to impeach Clinton, his approval rating among Democrats continued to climb, sitting in the high 80 per cent to low 90 per cent in late 1998 into early 1999. During Clinton’s trial in the Senate, Democrats gave Clinton approval ratings of 94 per cent, among the very highest in-party approval ratings observed over the 64 years of Gallup approval data. Roughly two-thirds of political independents approved of Clinton’s performance through this period, further evidence of the fact that there was no meaningful political appetite for removing Clinton from office outside of the Republican party.

These historical comparisons help us put Trump’s approval ratings in context. To be sure, Trump’s overall approval ratings are not high, especially relative to other presidents at this early stage of a presidential term. Trump’s approval numbers have fallen slightly over his term thus far, but the bulk of that movement has come from Democrats and Independents. Since late April 2017, less than 10 per cent of Democrats have approved of Trump; political independents rate Trump in the low 30s, down from high 30s to 40 per cent earlier shortly after Trump’s inauguration. Republican support for Trump has cooled somewhat, but continues to be overwhelmingly positive, sitting somewhere in the low to mid 80s in the last month of polls, down from the high 80s recorded in the opening months of his presidency.

This level of in-party support is typical for presidents in recent decades, as depicted in Figure 9. Trump enjoys levels of support from Republicans that are indistinguishable from the levels of in-party support LBJ, Nixon, and Reagan had at the comparable stage of their presidencies. Trump is underperforming Obama and George W. Bush, but overperforming Carter, Ford and Clinton. In short, there is nothing especially noteworthy about the high levels of in-party support Trump currently has. Like almost all presidents early in their first term, the presidents' fellow partisans overwhelmingly support the incumbent president. These approval data strongly suggest that Trump will not face an impeachment threat in the current Congress.

Mueller’s investigation: the wildcard?

My conclusion that impeachment of Trump seems unlikely is conditioned not just on the partisan balance of Congress, but also the current set of “facts on the ground”: what is accepted as “fact” with respect to Trump, ties between his associates and Russia, and what Trump may or may not have done with respect to the FBI investigation into these matters. At the time of writing, my assessment is that the established set of facts are insufficient to disrupt the bedrock of Republican support for Trump.

My close examination of the Nixon and Clinton cases suggest that I ought to qualify this conclusion, noting that Special Counsel Mueller’s investigation is just months old. At the same stage of Starr’s investigations into Clinton — or the various Watergate investigations — the eventual outcome was far from known. The fact that Republicans control both houses of Congress provides a vital political backstop for Trump, placing him in a far stronger position a priori than either Nixon or Clinton. Nonetheless, just months into the Watergate matter, it was not at all clear that Nixon would resign 19 months into his second term with impeachment a political certainty and removal from office not far behind.

The probability of Trump being removed from office isn’t zero, just very close to it. But while Robert Mueller’s and congressional investigations continue, the possibility of impeachment has to be entertained.

What changed for Nixon between his inauguration in January 1973 and his resignation in August of 1974? The answer lies with the steady release of information about the extent of Nixon’s involvement not with the Watergate break-in, but its cover-up. This was driven by investigative reporting and leaks to the media (especially Woodward and Bernstein at the Washington Post), multiple investigations into the Watergate break-in, connections to the White House and Nixon’s involvement in any cover-up, from:

- Judge Sirica, Chief Judge of United States District Court for the District of Columbia;

- the Senate “Watergate Committee” and its sensational, televised hearings through the summer of 1973;

- the investigation of Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox (appointed in May 1973) and his successor after the “Saturday Night Massacre”, Leon Jaworski;

- the investigation of the House Judiciary Committee.

Turning points were the testimony of Nixon aide John Dean to the Senate’s Watergate Committee, Nixon’s attempt to shut down the Special Prosecutor’s investigation in the “Saturday Night Massacre”, and the Supreme Court ruling that subpoenas for the White House taped conversations were not subject to executive privilege. As the extent of Nixon’s personal involvement with the Watergate cover-up were revealed, Republican support faltered and finally buckled.

Thus, logic would dictate that I concede that there is a possible path to Trump’s impeachment, depending on what Special Counsel Robert Mueller and other investigations reveal. I do not claim any special insight into what Trump may or may not have done. The probability of Trump being removed from office isn’t zero, just very close to it. While Mueller’s and congressional investigations continue, the possibility of impeachment — however a priori politically improbable — has to be entertained.

The scope of Mueller’s investigation

Note too the long arc connecting Watergate to Mueller’s investigation. In response to the Watergate scandal — and Nixon’s attempt to terminate the Special Prosecutor’s investigation — Congress passed the Ethics in Government Act of 1977, signed into law by President Carter. This Act created the Office of Independent Counsel, designed to operate at arm’s length from the executive branch, to undertake investigations where the Justice Department would have a clear conflict of interest. The locus classicus contemplated by the Act would be a la Watergate, where it was necessary to undertake an investigation of allegations of criminal wrongdoing by a close political associate of the attorney-general, such as the president or persons close to the president, where the attorney-general would have a clear conflict of interest.59

This Act provided the framework for investigations of the Reagan administration’s involvement in the Iran-Contra scandal. This investigation incurred $48.5 million in expenses and resulted in 11 convictions. Presidential pardons saw none of those convicted face imprisonment. The cost of the investigation, frustration as to its political motivations and perceived ineffectiveness saw enthusiasm for the Office of Independent Counsel wane.

Robert Mueller has considerable autonomy and discretion — the same investigative and prosecutorial functions of a US attorney — but far less so than Kenneth Starr had as independent counsel for the Clinton investigation.

The legislation establishing the Office of Independent Counsel was due to expire in 1992. Ironically, President Clinton supported and signed the Independent Counsel Reauthorization Act of 1994. Under this legislation, the attorney-general would request a panel of three judges — a “Special Division” of the DC Circuit of the federal judiciary60 — to choose an independent counsel. A president could not dismiss an independent counsel, who enjoyed a high degree of autonomy and secrecy with respect to the conduct of the investigation, resources and staffing. Independent counsel were obliged to report to Congress at least annually on their progress and had discretion on what and when to disclose to the public. The independent counsel had the authority to transmit to Congress any information he or she deemed relevant. Importantly, the Act required the independent counsel to “advise the House of Representatives of any substantial and credible information… that may constitute grounds for an impeachment”.61 It was under this Act that Kenneth Starr was appointed to investigate various allegations against Clinton and his associates, ultimately resulting in the investigation of the Lewinsky matter inter alia and Clinton’s impeachment in late 1998.

A sunset clause in the 1994 legislation saw the Office of Independent Counsel wind down with the end of the Starr investigation. Congress had very little appetite for empowering investigators with as much independence as Starr enjoyed as independent counsel. Instead, Justice Department investigations of the president and close associates of the president now occur via a “special counsel”, under rules set out in the US Code of Federal Regulations, Chapter 6. It is under these rules that Acting Attorney General Rod Rosenstein appointed Robert Mueller.

Mueller has considerable autonomy and discretion — the same investigative and prosecutorial functions of a US attorney — but far less so than Kenneth Starr had as independent counsel. For instance, the special counsel’s investigation can be expanded only when the attorney-general62 deems it necessary “in order to fully investigate and resolve the matters assigned, or to investigate new matters that come to light in the course of the investigation”.

Before the start of the US government’s fiscal year on 1 October, the special counsel must request reauthorisation from the attorney-general, who determines what is an appropriate budget. Unlike Starr — who operated under court supervision and reported to Congress — Mueller reports to the Justice Department. In particular, Mueller is required to file “Urgent Reports” notifying the Justice Department of “major developments” in any investigation that is “likely to receive national media coverage or congressional attention”.

Finally, note that:

At the end of an investigation… the special counsel submits a confidential report to the attorney general, who in turn must report to the chair and ranking member of the House and Senate Judiciary Committees. The attorney general must tell those lawmakers whether he blocked the special counsel from pursuing any investigative or prosecutorial step. But note that the lawmakers learn this only at the end of the special counsel’s tenure. The attorney general also decides what parts, if any, of the final confidential report should be made public.63

It is plausible that the Justice Department might well refer any additional allegations of wrong-doing by Trump to Mueller — or that Mueller might request an expansion of his remit — in the same way that Starr was referred additional matters beyond Whitewater. But my assessment of the legal framework empowering Mueller’s investigation suggests that it will not go on for years, like Starr’s, or even the investigations of Special Prosecutors Cox and Jaworski in the Watergate investigation.

Mueller could make adverse findings against Trump — that Trump engaged in conduct that constitute grounds for impeachment — or not. But ultimately, the question of impeachment remains where it has always resided, with Congress.

Overarching all of these considerations about Mueller’s powers is the political backstop of a Republican-controlled Congress. Mueller could bring prosecutions against members of the Trump campaign and administration, or not. Mueller could make adverse findings against Trump — that Trump engaged in conduct that constitutes grounds for impeachment — or not. But ultimately, the question of impeachment remains where it has always resided, with Congress.

Conclusion

The intensely political nature of impeachment — coupled with historically high levels of partisanship in contemporary US politics — makes it extremely unlikely that Trump will be impeached.

A number of things need to happen to alter this conclusion.

First, either the investigation by Special Counsel Mueller or by one of the other investigations into Trump's ties to Russian attempts to sway the 2016 election needs to reveal facts that damage the president among Republicans partisans and Republican members of Congress.

Second, it is possible that independent of any findings or allegations brought via any of the extant investigations, Trump's standing with Republicans falters, eroding his political capital and making Republicans more receptive to calls for Trump's impeachment. Here I again note that Trump currently has an approval rating among Republicans in high 80 per cent range. Until Republican support for Trump drops precipitously — closer to the 50 per cent levels recorded by Nixon towards the end of his presidency — impeachment would seem out of the question.

Alternatively, the partisan composition of both the House of Representatives and the Senate could tilt back towards Democrats at the 2018 midterm elections, putting the votes for impeachment within closer reach. There are currently 193 Democrats in the House of Representatives. Twenty-five Republicans would have to join every Democrat in an impeachment vote in the House for it to succeed. Alternatively, Democrats would have to win 25 Republican seats at the 2018 midterm elections in order to form a majority, allowing Democrats to carry an impeachment resolution without Republican votes. Even then, a Senate trial would require 67 votes for conviction and removal from office. Under any reasonable assumption about the partisan composition of the US Senate after the 2018 elections — and most forecasts do not see Democrats gaining Senate seats at this stage 64 — a sizeable number of Republican Senators would have to support conviction if Trump was to be removed from office.

These scenarios are speculative, perhaps even far-fetched. Accordingly, impeaching Trump seems extremely unlikely, at least for the time being.

Appendix: the long road to the impeachment of Bill Clinton

Whitewater and Vince Foster

Whitewater was a failed real estate venture in Arkansas, a partnership between the Clintons and James McDougal (a political backer of Bill Clinton) and his then wife Susan, dating to 1978. An investigation by The New York Times65 revealed (a) irregularities in documents and tax filings detailing the Clintons’ stake in the venture; (b) the possibility that as governor of Arkansas, Clinton gave favourable treatment to McDougal’s savings and loan association,66 a venture that subsequently failed; (c) that the savings and loan was exposed to the Whitewater venture and made payments to reduce the Clinton’s exposure; (d) that as a partner at the Rose Law firm, Hillary Clinton drafted advice to the struggling S&L to help it avoid closure by the state of Arkansas.

The New York Times article was published on 8 March 1992, well before Clinton had secured the Democratic nomination for the election to be held in November of that year, which Clinton of course won. Clinton was inaugurated on 20 January 1993. On 20 July 1993, Deputy White House Counsel Vince Foster committed suicide. Foster had been a partner at the Rose Law Firm and a colleague of Hillary Clinton and had handled Whitewater-related matters on behalf of the Clintons.

Foster’s suicide — later ruled a result of depression — renewed interest in Whitewater and the role of the Clintons. Political pressure continued to mount. Claims of a conspiracy mounted, fuelled by speculation about the circumstances of Foster’s death and the propriety of financial dealings between the Clintons and business figures in Arkansas.67 Of particular interest was the fact that Foster was in possession of Whitewater-related documents at the time of his death (held at his White House office) and that those documents were transferred to other parties in the White House. The White House acknowledged the presence of the documents at the White House on 20 December 1993.

On 12 January 1994, President Clinton asked Attorney-General Janet Reno to appoint a special counsel, taking over a Justice Department investigation of the financial dealings of parties in Arkansas, including the Clintons’ associates. Reno appointed Robert Fiske on 20 January 1994,68 with a mandate to investigate if crimes had been committed relating to the Clintons’ relationships with McDougal’s S&L and the Whitewater venture. Fiske also re-examined the death of Vince Foster. On 30 June 1994, Fiske issued an interim report, finding no improper ties between the Clintons and McDougal’s S&L and that Foster’s death was a suicide.

The Office of the Independent Counsel

President Clinton signed the Independent Counsel Reauthorization Act of 1994 on 1 July. In large measure this Act revived the Ethics in Government Act of 1978, which created the Office of the Independent Counsel and had been originally passed by a Democratic Congress under the Carter administration in response to the Watergate crisis. The Act had been amended in 1983 and 1987, but allowed to expire in December 1992; Republicans had not been eager to renew an office that had vigorously pursued the Iran-Contra matter under the Reagan administration and the constitutionality of the Act’s provisions had been vigorously challenged before the Supreme Court.69 Clinton had previously voiced his support for reinstating the OIC, and now, with Whitewater firmly on the national agenda, Republicans enthusiastically agreed.

An independent counsel was designed to operate at arm’s length from the executive branch, to undertake investigations where the Justice Department would have a clear conflict of interest; the contemplated locus classicus would be a la Watergate, where it was necessary to undertake an investigation of allegations of criminal wrongdoing by a close political associate of the attorney-general, such as the president or persons close to the president.70

Under the Act, the attorney-general would request a panel of three judges — a “Special Division” of the DC Circuit of the Federal judiciary71 — to choose an independent counsel. A president could not dismiss an independent counsel, who enjoyed a high degree of autonomy and secrecy with respect to the conduct of the investigation, resources and staffing. Independent counsel were obliged to report to Congress at least annually on their progress and had discretion on what and when to disclose to the public. The independent counsel had the authority to transmit to Congress any information he or she deemed relevant. Importantly, the Act required the independent counsel to “advise the House of Representatives of any substantial and credible information… that may constitute grounds for an impeachment”.72

Reno asked that Fiske be reappointed as independent counsel under the revived Act, an “upgrade” of sorts from his appointment as a special counsel under the Justice Department.73 The Special Division disagreed, stating that Fiske’s reappointment “would not be consistent with the purposes of the [Independent Counsel Reauthorization] Act”.74

The Special Division appointed Kenneth Starr to take over as independent counsel of the Whitewater matter. Starr had served as counsellor to President Reagan’s attorney-general and then as solicitor-general in the Bush administration. Almost immediately, Democrats raised questions about Starr’s independence, along with that of the judges appointing Starr in place of Fiske.75 Starr requested and was granted authority to examine the death of Vince Foster, the first of several expansions of Starr’s investigation.

Congressional investigations of Whitewater continued at the same time. In early 1994, after the Clinton administration appointed Fiske, congressional Republicans were clamouring for more action from congressional committees with Democratic majorities. According to a media report at the time:

Republicans had hoped for separate hearings into Whitewater, but those hopes faded when a special prosecutor was named to look into the affair earlier this month. Many legislators worried that a formal inquiry with immunized witnesses could impede a criminal investigation, just as 1987 hearings on the Iran-Contra affair hamstrung subsequent trials in that scandal.76

Republicans won control of both houses of Congress in the 1994 midterm elections. On 17 May 1995, the US Senate established the Senate Whitewater Committee77 chaired by Republican Senator Alfonse D’Amato (NY).78 The Senate Whitewater Committee would sit for hundreds of hours over 13 months and produce a report of more than 600 pages on 17 June 1996, issue many subpoenas and demand (with mixed success) documents from both the White House79 and the Starr investigation.

In the summer of 1995, Monica Lewinsky graduated from college and joined the White House staff as an unpaid intern, accepting a paid position in November. Lewinsky left the White House in April 1996, but was a frequent visitor to the White House through to the end of 1997. Starr, the Congress and the media were focused on Whitewater and other matters up until late 1997.

Charges of bank fraud were brought against the McDougals and Arkansas Governor Jim Guy Tucker80 in August 1995. They were convicted in May 1996.81 Starr first interviewed both Clintons in April 1995. Long missing documents82 detailing work done by Hillary Clinton at the Rose Law Firm for McDougal’s S&L surfaced in January 1996; Starr subpoenaed Hillary Clinton to determine if the documents were intentionally withheld. A second Whitewater trial began in June 1996, this time ending in acquittals.83

In early 1997 Starr announced he would resign as independent counsel84 and many thought the saga of independent investigations into the Clinton White House was winding down. Within days, and after “heavy criticism from some prominent Republicans”,85 Starr reversed his decision.86 Starr postponed taking up a deanship at Pepperdine University, finally declining the Pepperdine appointment in April 1998.87

Paula Jones and Monica Lewinsky

On 6 May 1994, Paula Jones filed a civil suit against President Clinton in the US District Court in Arkansas, seeking damages for (a) sexual harassment and assault by Clinton, alleged to have taken place in May 1991, (b) defaming Jones by denying the accusations. Clinton’s defence included a claim that a private litigant could not sue a sitting President. This claim worked its ways through the courts over almost three years; in May 1997 the Supreme Court which unanimously rejected the Clinton claim. Jones vs Clinton was set for trial in May 1998.

Part of the Jones legal strategy was to demonstrate a pattern of behaviour by Clinton, that the allegation of Clinton’s harassment and assault of Jones was credible because other women had similar episodes to report. To this end, Jones’ legal team deposed Dolly Kyle Browning, Gennifer Flowers and Kathleen Wiley in October 1997.

By July 1997, Lewinsky had confided her relationship with Clinton to her co-worker, Linda Tripp. Tripp began taping her phone conversations with Lewinsky in September 1997. In October 1997, the Jones legal team received anonymous tips about a sexual relationship between Lewinsky and Clinton.88 Tripp was subpoenaed in the Jones case in November and Lewinsky in December 1997. It was later revealed that Lewinsky was regularly visiting or communicating with Clinton and Clinton adviser Vernon Jordon about Lewinsky’s relationship with Tripp, and securing employment and legal representation for Lewinsky. On 7 January 1998, Lewinsky filed an affadavit — later revealed to be knowingly false and conceived in concert with Tripp — denying any sexual relationship with Clinton. On 12 January 1998, Tripp turned over her taped conversations with Lewinsky to Starr.

Three days later, Starr requested that his investigation be expanded; Attorney-General Reno petitioned the Special Division accordingly. On 16 January 1998 the Special Division granted Starr authority to investigate:

- “whether Monica Lewinsky or others suborned perjury, obstructed justice, intimidated witnesses, or otherwise violated federal law… concerning the civil case Jones vs Clinton.”

- “related violations of federal criminal law… including any person or entity who has engaged in unlawful conspiracy or who has aided and abetted any federal offense.”

- “any obstruction of the due administration of justice, or any material false testimony or statement in violation of federal criminal law.”89

The next day, Clinton was deposed in the Jones suit. Clinton testified that he did not have sexual relations with Lewinsky, according to a specific definition of “sexual relations” handed to him by Lewinsky’s attorneys.

Finally, on 21 January 1998, news of the Lewinsky scandal broke in mainstream media.90 Clinton denied encouraging Lewinsky to lie in her Jones affidavit and denied any affair with Lewinsky.91 Clinton famously issued a televised denial on 26 January.

On 29 January, in response to a motion from Starr, the judge presiding in the Jones suit ruled that all evidence relating to Lewinsky be excluded in deference to Starr’s investigation. In April 1998, the Jones suit was dismissed. Starr’s investigation continued.

In July and August, Lewinsky was questioned by Starr and his staff over 15 days, after an agreement was negotiated granting her immunity. Lewinsky admitted to the Starr investigation that she did have a sexual relationship with Clinton.

On 18 August 1998, Clinton testified to a grand jury convened by Starr that he had had an intimate relationship with Lewinsky. In a televised address that evening, Clinton conceded that his testimony in the Jones case was “legally accurate” but that he “did not volunteer information”.[92] Clinton further conceded that he “did have a relationship with Miss Lewinsky that was not appropriate”. Clinton went on to attack the (dismissed) Jones lawsuit as “politically inspired” and that he had “real and serious concerns” about Starr’s inquiry that began with “private business dealings 20 years ago” and had since “moved on to my staff and friends, then into my private life”.

Starr’s Report

Starr submitted a lengthy report on the Lewinsky matter to the House of Representatives on 9 September 1998,93 which came to be known simply as the “Starr Report”. With the possible exception of the US Constitution, it is perhaps the most widely read document ever produced by the US government and dominated best-seller lists in the weeks after its publication.94 Details of Clinton and Lewinsky’s sexual encounters saw the document flagged with cautions about its “explicit content” and were no doubt key to the report’s popularity.95 Starr sought — and was granted — permission from the courts to release Clinton’s grand jury testimony96 and some four hours of video of Clinton’s grand jury testimony — in which he conceded having an inappropriate, intimate relationship with Lewinsky — aired on national television on 21 September 1998.97

Kenneth Starr submitted a lengthy report on the Monica Lewinsky matter to the House of Representatives. With the possible exception of the US Constitution, it is perhaps the most widely read document ever produced by the US government.

As for the timing of his report to Congress, Starr noted that he had wished to complete his investigations before deciding whether to submit to Congress information (if any) that might constitute grounds for impeachment. But, said Starr, “events and the statutory command of Section 595(c) have dictated otherwise”:

As the investigation into the President's actions with respect to Ms. Lewinsky and the Jones litigation progressed, it became apparent that there was a significant body of substantial and credible information that met the Section 595(c) threshold. As that phase of the investigation neared completion, it also became apparent that a delay of this Referral until the evidence from all phases of the investigation had been evaluated would be unwise. Although Section 595(c) does not specify when information must be submitted, its text strongly suggests that information of this type belongs in the hands of Congress as soon as the Independent Counsel determines that the information is reliable and substantially complete. (p9, H.D. 105-310)