Executive summary

Key judgements

- Although the Quad has emerged as a bulwark of a free, open and resilient Indo-Pacific and a leading provider of public goods, it is not living up to its potential as a contributor to regional security and defence in the maritime domain.

- This is a problem for Indo-Pacific security. Given its member states’ collective military heft and stated interest in upholding a favourable balance of power in the region, the Quad has a vital role to play in preserving stability and deterring major power aggression.

- Today, this is needed more than ever as China’s growing military capabilities and coercive statecraft challenge the foundations of regional order from the Himalayas and the Indian Ocean to Northeast Asia, the South China Sea, and the South Pacific.

- While Quad countries have pursued an array of defence agreements, military exercises, and maritime security initiatives at the “Quad-minus” level, these are not comprehensive, nor have they been networked and standardised in ways that facilitate effective operational collaboration between all four members.

- The main reason for this is that a set of political sensitivities and geostrategic concerns has prevented Quad countries from embracing this kind of collective security agenda.

- But these constraints are beginning to lessen as the Quad steps up its mission to deliver collective public goods, and as its members come to recognise China as a common military challenge that requires a degree of collective action and security coordination to address.

- This does not mean the Quad can or should pursue a formal collective defence framework. But it does mean Quad countries should be able to better leverage and network their respective capabilities to advance a collective approach to defence cooperation on key maritime security tasks of mutual interest and significant value to the region.

- The Quad should capitalise on this diplomatic opportunity and geostrategic imperative to pursue a collective maritime security strategy across five high-priority areas: maritime domain awareness; anti-submarine warfare; maritime logistics; defence industrial and technological cooperation; and maritime capacity building.

Recommendations

This report lays out a case and provides a menu of policy options for how the Quad can pursue a collective approach to Indo-Pacific maritime security, with a particular focus on regional deterrence and defence.

On collective maritime domain awareness, the Quad should:

- Develop a more networked and persistent maritime domain awareness (MDA) capability as a foundation for tracking activities of interest across geographic areas of responsibility, including as a baseline for potential coordinated efforts to build a comprehensive, real-time picture of Chinese military movements.

- Discuss the limitations of existing tactical data link arrangements within the Quad, and work towards an interface protocol to govern information-sharing between all Quad partners, with particular attention paid to a commonality of hardware and software or, at the least, interoperability of different tools.

- Update bilateral information security agreements and pursue a multi-party agreement to enable Quad countries to develop a more holistic operating picture of activities of interest across the Indo-Pacific.

- Selectively integrate Quad countries’ coastal facilities, island territories and regional access locations to conduct more persistent and coordinated MDA operations; and jointly assess the requirements of hosting and replenishing one another’s MDA assets like maritime patrol aircraft.

- Set up MDA and intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) initiatives that combine shared access, information-sharing and analysis, and platform interoperability to create a common operating picture within geographically defined Quad groupings.

On coordinated anti-submarine warfare operations, the Quad should:

- Build collective anti-submarine warfare (ASW) capability by developing higher levels of interoperability and more persistent patterns of unscripted cooperation to include tracking and “handing off” overwatch responsibility for Chinese submarines transiting geographic areas of responsibility.

- Develop mechanisms to conduct joint assessments of underwater domain awareness (UDA) data gathered by national sensors, towed acoustic arrays, ASW aircraft and unmanned vehicles, focusing on agreed-upon areas of operation with an eye towards joint collection in the future.

- Establish service- or bureaucratic-level mechanisms for conducting four-way combined assessments of underwater domain information from select areas, and work towards a formal classified sharing network for the development and dissemination of key submarine-related intelligence.

- Identify the necessary upgrades to existing bilateral agreements and access locations required to support more frequent coordinated aerial ASW activities.

On integrated maritime logistics, the Quad should:

- Develop the collective capacity to seamlessly refuel, resupply and repair maritime assets from any member on short notice, and formally commit to this agenda at the political and operational levels.

- Establish a Quad Logistics Coordination Cell within the US Navy’s Commander, Logistics Group Western Pacific that incorporates all four partners and performs logistics planning for the Indian and Pacific Oceans, using combined maintenance and resupply capabilities on a regular basis.

- Elevate maritime logistics discussions to the Quad Maritime Security Working Group to promote information-sharing on bilateral and trilateral logistics activities, pursue opportunities for aligning or networking concurrent activities, and develop options for Quad logistics planning, exercises and operations.

- Conduct a Quad-wide equipment interoperability review to ensure logistics compatibility and procedural standardisation, and support this with a framework and requirement for placing Quad liaisons on one another’s logistics vessels to encourage familiarity and exchange best practices.

On defence industrial and technology cooperation, the Quad should:

- Establish a Quad Initiative for Maritime Security Capabilities within the existing Maritime Security Working Group to assess individual and collective maritime defence requirements, identify opportunities for and barriers to collaboration, and advance cooperation on interoperable maritime capabilities.

- Launch a defence supply chain mapping project with an initial focus on critical lethal and non-lethal items, like sonobuoys and long-range anti-ship missiles, used across common platforms such as the P-8 maritime patrol aircraft.

- Explore collective supply chain innovations for in-demand capabilities by emulating the Quad Vaccine Initiative model, including its joint financing and distributed production arrangements.

- Establish formal training programs and embed arrangements to train Quad officials and industry representatives on one another’s defence procurement systems and processes, building on the model being developed by Japan’s Acquisition, Technology and Logistics Agency (ATLA) for Indian counterparts.

On coordinated maritime capacity building, the Quad should:

- Establish a Maritime Capacity Building Initiative (MCBI) to expand Quad efforts to strengthen the maritime security capabilities of key Southeast Asian partners and operate as a “clearing house” to align efforts, share information and eliminate duplicative programs.

- Co-design and co-administer coast guard training programs for Southeast Asian partners, with a view to establishing a Quad Coast Guard Working Group.

- Set up an integrated working group within the MCBI to identify opportunities for Quad countries to provide complimentary platforms to Southeast Asian partners, with a focus on MDA, ISR, and patrol assets.

- Scope options to collectively provide joint force integration assistance programs that support Southeast Asian nations to achieve higher levels of interoperability between their legacy, often Russian-sourced forces, and newly-acquired Western capabilities from multiple suppliers.

- Undertake a pilot program to collectively refurbish existing Quad capabilities for transfer to Southeast Asian partners.

Introduction

The Quad has emerged as one of the Indo-Pacific’s premier minilateral forums and a bulwark of a free, open and resilient region. Ever since Australia, India, Japan and the United States restarted the grouping in 2017, its achievements have been swift and far-reaching. The Quad now encompasses an annual leaders’ summit and foreign ministers’ meeting. It has established working groups to deliver practical “public goods” for regional countries in areas ranging from global health and critical technologies to climate, infrastructure and space. And it has gone out of its way to foster new “habits of cooperation” among its four members and other Indo-Pacific partners in support of a more peaceful, stable and prosperous region.1

But the Quad is not living up to its potential as a contributor to regional security and defence in the maritime domain. Although the grouping has made substantial investments in non-traditional maritime security, like humanitarian assistance and disaster relief, and is delivering valuable public goods through the 2022 Indo-Pacific Maritime Domain Awareness initiative, its quadrilateral efforts have not prioritised coordination on issues relating to traditional deterrence and defence. The situation is very different at the Quad-minus level, where members have pursued a vast array of agreements and maritime security initiatives to deepen operational cooperation in areas like maritime domain awareness, anti-submarine warfare and logistics support. These, in effect, represent the bilateral building blocks of what could become a Quad-wide approach to collective maritime security. At present, however, these Quad-minus arrangements are neither comprehensive nor have they been sufficiently networked and standardised to facilitate effective defence collaboration between all four Quad countries. When it comes to high-end maritime security and defence cooperation, the Quad is still less than the sum of its parts.

When it comes to high-end maritime security and defence cooperation, the Quad is still less than the sum of its parts.

This is a serious problem for Indo-Pacific security. Given its members’ collective military heft and stated interest in upholding a favourable balance of power in the region, the Quad has a potentially vital role to play in preserving stability and deterring major power aggression. Today this is needed more than ever as China’s growing military capabilities and coercive statecraft is challenging the foundations of regional order from the Himalayas and the Indian Ocean to Northeast Asia, the South China Sea and the South Pacific. These developments, to be sure, are not lost on individual Quad countries. All four have recently come to recognise China as a common military challenge that is better addressed through collective action and security coordination, especially in areas where Beijing is seeking to coerce others on territorial disputes. All are in the midst of major defence build-ups designed to improve their national capacity to deter and defend against China’s rising power, spurred on by an uptick in Chinese assertiveness in places like the Sino-Indian border and the East and South China Seas. And all are pursuing a growing schedule of defence cooperation with like-minded regional partners as a way of bolstering their ability to shape and defend the deteriorating strategic environment. Better aligning these efforts within the Quad to ensure its members have a common capacity to operate together in support of shared deterrence and defence objectives would make an invaluable contribution to Indo-Pacific stability and maritime security.

There are longstanding reasons why this has not happened. A set of political sensitivities and geostrategic concerns has prevented the four countries from embracing a Quad-wide defence agenda. These include differently weighted strategic priorities, India’s place outside the US alliance network, anxiety about losing regional support for the Quad, concerns about diluting the Quad’s public goods agenda, and a lack of bureaucratic capacity and domestic support. Yet, many of these constraints are beginning to lessen as the Quad steps up its overall mission to deliver collective public goods to the region and as the collective demands of strategic competition with China become more apparent to its members. This does not mean the Quad is able to embrace an explicit collective defence framework within the grouping, which, in any case, would almost certainly be counterproductive for its wider regional order agenda at this time. But it does mean that Quad countries should now be in a position to better manage existing constraints and leverage their collective capabilities to advance a Quad-wide approach to defence cooperation on key maritime security tasks of mutual interest and value to the region.

This report lays out a case for how the Quad can pursue this kind of collective approach to Indo-Pacific maritime security, with a particular focus on regional deterrence and defence. Departing from the premise that there is a geostrategic imperative and diplomatic opportunity to galvanise Quad countries into action on this front, we argue the Quad can — and should — strengthen its existing network of cross-bracing defence agreements and maritime security arrangements to facilitate deeper operational collaboration across the Indo-Pacific. Specifically, we outline five high-value and achievable tasks that the Quad should prioritise as part of this agenda. These are:

Collective maritime domain awareness;

- Coordinated anti-submarine warfare operations;

- Integrated maritime logistics;

- Defence industrial and technological cooperation; and

- Coordinated maritime capacity building.

For each of these, we also set out detailed policy recommendations for decision-makers to consider as part of implementing particular aspects of this approach. Above all, we argue that by making a deliberate effort to consolidate, standardise and expand Quad-wide efforts in each of these areas, Australia, India, Japan and the United States could bolster their independent and collective capacity to strengthen maritime security and promote regional stability.

It is important to note what we are, and are not, advocating in this report. First, although our focus is on how the Quad should contribute to collective security and defence in the maritime domain, we view this as simply one part of its overall agenda to bolster regional resilience through the provision of “public goods” in a range of areas. We certainly do not advocate reducing the Quad to defence cooperation alone. Second, we do not call for the adoption of a Quad-wide defence strategy, nor do we recommend that enhanced areas of cooperation on maritime security be branded as “Quad” initiatives per se. Both are unnecessary and would risk alarming the Quad’s regional partners without making concrete contributions to collective security. Third, we do not think China should be the sole focus of the Quad’s maritime security agenda. While we urge the Quad to foster certain capabilities, like coordinated anti-submarine warfare, that could be used to deter or defend against Chinese aggression in high-priority scenarios, we see its development of collective maritime security arrangements as having broader applicability.

Finally, although our recommendations are geared towards preparing the Quad to be a more effective collective security actor, we recognise the Quad’s strength will remain a function of its key bilateral relationships and that real-world defence cooperation will rarely involve all of the Quad operating together all of the time. Indeed, the core of our argument is that the Quad has already made important progress at the Quad-minus level towards enabling collective action between its members and has untapped potential to advance this agenda quadrilaterally should its leaders so choose. To this end, we endeavour to explain how the Quad can consciously build out its collective capability so that members can more seamlessly support each other’s maritime security operations or work together in providing regional security goods on the basis of geographical divisions of labour or formally coordinated responsibilities.

The remainder of this report is divided into two parts. In part one, we lay out the current state of the Quad’s maritime security contributions by unpacking its constituent bilateral partnerships. We examine the value of key Quad-minus defence agreements and maritime security arrangements, including the annual Malabar naval exercise, teasing out the gaps in this so-called “cross-bracing” framework for Quad-wide cooperation and detailing the evolution of constraints to a more coordinated Quad maritime security agenda. In part two, we make the case for how the Quad can advance a more collective approach to maritime security in five priority areas: maritime domain awareness, anti-submarine warfare, logistics support, defence industrial and technological cooperation, and maritime capacity building. In each case, we explain the strategic rationale for enhanced quadrilateral action, present detailed recommendations for how this could be achieved, and articulate the value of Quad-wide cooperation in these areas for enhancing maritime security across the Indo-Pacific region.

Part A: The state of play

The building blocks of a collective strategy

Although the Quad has eschewed a collective defence agenda in the maritime domain, its members have individually advanced this strategy through a burgeoning range of Quad-minus arrangements at the bilateral and trilateral levels. This process has not been centrally driven by the Quad and will require coordination to meaningfully progress. But it has nonetheless produced a suite of foundational agreements, military exercises and patterns of high-end security cooperation on which a more structured Quad maritime defence strategy can be developed.2

While these are not yet comprehensive, the overall patchwork of cross-bracing security arrangements provides a solid basis for networking and expanding Quad-wide defence cooperation.

At the time of writing, most Quad countries have signed agreements with their counterparts for information- and intelligence-sharing, acquisition and logistics support, and defence industrial and technology cooperation. While these are not yet comprehensive, the overall patchwork of cross-bracing security arrangements provides a solid basis for networking and expanding Quad-wide defence cooperation.3 The annual Malabar naval exercise — which has become synonymous with the Quad since Australia re-joined in 2020, despite its members’ protestations that it is not a formal Quad activity — highlights the growing appetite and potential for security cooperation within the Quad. Meanwhile the increasingly sophisticated nature of high-end maritime security cooperation among the Quad’s constituent bilaterals, albeit at very different speeds and levels of sophistication, represents the building blocks of a nascent collective deterrence capability.

The state of the bilaterals

The United States and its closest regional treaty allies, Japan and Australia, have made great strides towards a strategy of collective deterrence and defence in the maritime domain. Over the past decade, Washington and Tokyo have embarked on a far more integrated approach to defence planning and operations, with Japan’s 2015 Peace and Security legislation expanding the aperture for Tokyo’s participation in defence activities short of homeland defence and prompting an update to alliance guidelines and agreements.4 Indeed, even before the watershed changes to Japan’s defence posture brought about by its 2022 National Security Strategy, the US-Japan alliance was steadily accelerating its integration agenda in important ways: exploring combined high-end contingency planning (including joint counterattack and intelligence-sharing planning), launching new joint defence technology development initiatives, expanding the number of joint facilities and stockpiles in Japan, and establishing new mechanisms for joint, real-time information analysis in the maritime domain.5 Naval exercises between the United States and Japan have also expanded in scope and scale, with a growing focus on multi-domain anti-submarine warfare (ASW) operations in the Western Pacific, the South China Sea,6 and Japan’s Nansei Island chain close to Taiwan.7

The US-Australia alliance has similarly become a key node in collective efforts to uphold a favourable balance of power in the region. Bilateral Force Posture Initiatives established in 2011 were updated in 2021 to facilitate expanded US Air Force, Marine Corps, Army and Navy rotations through Australian facilities, and to establish a combined logistics, sustainment, and maintenance enterprise to support high-end military operations in the region.8 In a new direction for the alliance, Washington and Canberra are in the early stages of developing more coordinated military- and contingency-planning processes,9 as well as deeper forms of defence industrial and technological integration through the trilateral AUKUS partnership which, beyond supporting Australia’s acquisition of nuclear-powered submarines, is designed to generate collective progress on emerging capabilities such as unmanned underwater vehicles, hypersonic missiles, artificial intelligence, quantum and advanced cyber.10 Meanwhile, Australia-US naval exercises have displayed greater proficiency in “enhanced maritime communication tactics, electronic warfare operations and integrated anti-air, anti-surface operations,”11 with a growing roster of multilateral engagements featuring other capable regional powers like Japan and South Korea through Exercise Sea Dragon and Pacific Vanguard, respectively.

The United States, Japan and Australia are simultaneously working to align these bilateral alliance efforts to “enable higher capability defence exercises and operations” through the Trilateral Strategic Dialogue.12 A new Joint Vision Statement released in 2022 flagged enhanced training opportunities, more coordinated responses to regional crises, and the development of a trilateral Research, Development, Testing and Evaluation (RDT&E) framework to promote deeper cooperation on advanced technologies and strategic capabilities.13 This was followed by an invitation by Australia and the United States to integrate Japan into the Australia-US Force Posture Initiatives announced at AUSMIN 2022.14 Such efforts to build out this collective defence grouping build on a growing tempo of sophisticated trilateral exercises and operations in the South China Sea and Western Pacific.15

The United States and India have gradually expanded military cooperation in line with bilateral efforts to sign four foundational security agreements on information-sharing and logistics cooperation, the last of which was secured in 2020.16 Successive bilateral naval drills have sought to develop “high-calibre integration” between the two partners in areas such as anti-submarine warfare, air defences and maritime domain awareness.17 Outside of structured exercises, the US and Indian navies have occasionally provided each other with mutual logistics and replenishment support, including, most notably, the decision to service an American P-8A maritime patrol aircraft at Indian facilities on the Andaman and Nicobar Islands during the 2020 India-China stand-off in the Himalayas.18 Officials have since flagged an increase in coordinated sea patrols, information-sharing in underwater domain awareness, and the use of Indian ports to support US Transport Command assets transiting the Indian Ocean.19 While India has purchased greater numbers of American maritime platforms in recent years,20 the two countries have also finally begun to pursue co-development projects through the 2012 Defence Technology Trade Initiative (DTTI),21 with an inaugural co-development project in air-launched unmanned aerial systems announced in 2021.

Beyond their relations with the United States, Australia, India and Japan have accelerated their own cooperative security frameworks and pursued more complex maritime exercises and operations.

Beyond their relations with the United States, Australia, India and Japan have accelerated their own cooperative security frameworks and pursued more complex maritime exercises and operations. In the past decade, Australia and Japan have significantly widened the aperture of their defence cooperation, elevating bilateral security cooperation to the highest level possible short of a formal alliance. The 2010 Acquisition and Cross-Servicing Agreement (ACSA) was updated in 2017 to bring logistics cooperation “fully into line” with Japan’s 2015 Peace and Security Legislation.22 Significantly, the bilateral Exercise Nichi Gou Trident in 2021 saw Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF) vessels conduct “asset protection” operations for Royal Australian Navy (RAN) ships, marking the first time such operations were conducted by Japan in support of a non-US partner.23 The ratification of the 2021 Reciprocal Access Agreement by the Japanese Diet will facilitate more frequent rotations of Japan Air Self-Defense Force (JASDF) fifth-generation fighters and Amphibious Rapid Deployment Brigade personnel through Australian facilities,24 as well as more frequent visits by Australian aircraft and warships to Japanese facilities.

After a relatively slow start, Australia-India maritime defence engagements have also advanced quickly.25 Anti-submarine warfare and maritime domain awareness have become focal points for bilateral engagements, with specialist vessels, submarines and maritime patrol aircraft from both countries now featuring regularly in biennial naval drills.26 These exercises support an emerging pattern of coordinated airborne maritime patrol missions in the Eastern Indian Ocean,27 enabled chiefly by the implementation of the 2020 Mutual Logistics Support Arrangement.28 In early 2022, Australia and India conducted reciprocal visits of P-8 aircraft to Darwin and Goa, respectively, in an effort to further strengthen bilateral ASW and MDA capabilities.29 These engagements included coordinated patrols over strategic waterways off Northern Australia,30 demonstrating the two countries’ mutual interest in monitoring maritime chokepoints in littoral Southeast Asia and the eastern Indian Ocean. India and Australia’s converging interests in ASW and MDA appear to be paving the way for bilateral discussions on “longer-term reciprocal access arrangements” to support combined maritime surveillance operations in the region.31

Finally, India and Japan have also advanced bilateral defence ties,32 albeit more slowly, and are moving to deepen cooperation “across the entire spectrum of maritime operations.”33 The main avenues for this have been the annual Maritime Partnership Exercises and Japan-India Maritime Exercise,34 recent editions of which have showcased real-time information exchanges and divisions of labour for situational and domain awareness during complex, coordinated submarine hunting and over-the-horizon targeting exercises.35 New Delhi and Tokyo have also taken advantage of multilateral naval exercises to operationalise foundational agreements, with the 2020 Agreement Concerning Reciprocal Provision of Supplies and Services implemented for the first time during Exercise MILAN in March 2022.36 Senior leaders have further identified maritime domain awareness as a key vector for enhancing operational cooperation and emphasised the “vast potential” for expanding cooperation on defence equipment and technology beyond its present focus on unmanned ground systems.37

Malabar: A microcosm for the Quad’s transformation

This web of increasingly robust bilateral security cooperation and cross-bracing agreements provides a solid foundation for the Quad to pursue a more collective approach to deterrence and defence in the maritime domain. Although such a strategy has not been officially embraced, the evolution of Exercise Malabar since 2020 — when Australia’s re-inclusion transformed it into the Quad’s only all-member naval activity — highlights just how far the Quad has moved in the direction of high-end maritime security cooperation in a short period of time.38 This offers a preview of what the Quad could achieve in terms of practical maritime security cooperation if its members actively leverage and network the growing potential of their bilateral relationships. Although Exercise Malabar does not represent a formal military agreement between Quad members, it reflects the avenues and platforms that are available to all four members to enhance common interests in the maritime domain.

Figure 1. Quad maritime access locations in the Indo-Pacific and Exercise Malabar locations

Sources: Department of Defence, India Ministry of Defence, Japan Ministry of Defence, US Department of Defense265

Initially designed to familiarise India and the United States with each other’s procedures for maritime operations,39 Exercise Malabar has recently evolved into a complex set of high-end naval activities.40 This has happened relatively quickly. Whereas the 2018 and 2019 drills focused on less complex combined operations and professional training between the United States, India and Japan,41 following Australia’s re-invitation to Malabar in 2020, the exercise has begun to actively focus on enhancing “integrated maritime operations” between all four Quad countries (see Figure 2).42

Figure 2. Major participants in Exercise Malabar, 2019-2022

| Australia | India | Japan | United States | ||

| Malabar 2019 | Sasebo, Japan | - | INS Sahyadri (F49, Stealth Frigate), INS Kiltan (P30, ASW Corvette),1 x P-8I Neptune | JS Kaga (DDH-184, Helicopter Carrier) JS Samidare (DD-106, Destroyer), JS Choukai (DDG-176, Destroyer),1 x Kawasaki P-1 | USS McCampbell (DDG-85, Destroyer), 1 x LA-Class Submarine, 1 x P-8A Poseidon |

| Malabar 2020 | Phase I Bay of Bengal, Eastern Indian Ocean | HMAS Ballarat (FFG 155, Frigate) | INS Shakti (A57, Fleet Tanker), INS Ranvijay (D55, Destroyer), INS Shivalik (F47, Stealth Frigate), INS Sindhuraj (S57, submarine), 1 x P-8I Neptune (maritime patrol aircraft), 1 x Dornier 228 (maritime patrol aircraft) | JS Ōnami (DD 111, Destroyer) | USS John S. McCain (DDG 56) |

| Phase II Northern Arabian Sea, Western Indian Ocean | HMAS Ballarat (FFG 155, Frigate) | INS Vikramaditya (CV 1, Aircraft Carrier), INS Kolkata (D63, Destroyer), INS Chennai (D65, Destroyer), INS Talwar (F40, Stealth Frigate), INS Deepak (A50, Fleet Tanker), INS Khanderi (S22, Submarine), 1 x P-8I Neptune (maritime patrol aircraft), 1 x IL-38 Doplhin (maritime patrol aircraft) | JS Murasame (DD 101, Destroyer) | USS Nimitz (CVN, Aircraft Carrier), USS Princeton (CG 59, Cruiser), USS Sterett (DDG 104, Destroyer), 1 x P-8A Poseidon | |

| Malabar 2021 | Phase I Guam, Philippine Sea | HMAS Warramonga (FFH 152, Frigate) | INS Shivalik (F47, Stealth Frigate), INS Kadmatt (P29, ASW Corvette), 1 x P-8I Neptune | JS Kaga (DDH 184, Helicopter Carrier), JS Murasame (DD 101, Destroyer), JS Shiranui (DD 120, Destroyer), 1 x Kawasaki P-1 | USS Barry (DDG 52, Destroyer), USNS Rappahannock (T-AO 204, Underway Replenishment Oiler), 1 x P-8A Poseidon |

| Phase II Northern Arabian Sea, Western Indian Ocean | HMAS Ballarat (FFH 155, Frigate), HMAS Sirius (O 266, Fleet Replenishment Oiler) | INS Ranvijay (D55, Destroyer), INS Satpura (F48, Stealth Frigate), 1 x P-8I Neptune | JS Kaga (DDH 184, Helicopter Carrier), JS Murasame (DD 101, Destroyer) | USS Carl Vinson (CVN 70, Aircraft Carrier), USS Lake Champlain (CG 57, Cruiser), USS Stockdale (DDG 106, Destroyer), 1 x P-8A Poseidon | |

| Malabar 2022 | Yokosuka, Philippine Sea | HMAS Arunta (FFH 151, Frigate), HMAS Stalwart (submarine), HMAS Farncomb (SSG 74, submarine), 1 x P-8A Poseidon | INS Shivalik (F 47, Stealth Frigate), INS Kamorta (P 28, Stealth Corvette), 1 x P-8I Neptune | JS Hyuga (DDH 181, Helicopter Destroyer), JS Shiranui (DD 120, Destroyer), JS Takanami (DD 115, Destroyer), JS Oumi (AOE 426, Replenishment Ship), 1 x Kawasaki P-1 | USS Ronald Reagan (CVN 76), USS Chancellorsville (CG 62, Cruiser), USS Milius (DDG 69, Destroyer) |

Sources: Indian Navy, US Navy266

In practical terms, naval drills have progressed from basic air defence, surface warfare, at-sea replenishment, search-and-rescue and communications exercises to feature increasingly sophisticated anti-submarine warfare (ASW) activities — including submarine integration efforts43 — maritime patrol and reconnaissance, combined operations, interdiction and nascent efforts to explore “joint warfighting planning scenarios.”44 Malabar 2021 expanded the scope of drills to explicitly encompass grey zone or “irregular maritime threats” as well as conventional maritime security challenges, reflecting shared concerns over China’s use of maritime militias.45 These engagements have allowed Quad countries to practice sharing less-sensitive and unclassified forms of military information relevant to ASW and MDA, including water temperature and seabed geography, in the absence of Quad-wide procedures for sharing classified information for tactical or operational purposes.46

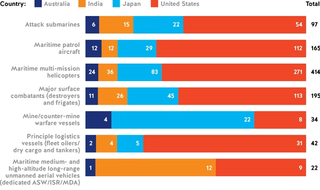

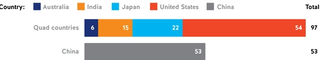

The sophistication of these exercises has been mirrored in the quantity and quality of participating platforms. In 2020, Malabar included both Indian and US aircraft carriers for the first time, training for “dual carrier” operations alongside supporting forces from Australia and Japan. A year later, Malabar 2021 became the largest on record with each country dispatching large numbers of advanced air and naval assets (see Figure 1). The 2022 exercises featured maritime patrol aircraft from all four countries for the first time, alongside surface and subsurface vessels outfitted for high-end ASW operations.47

The increasingly sophisticated nature of the Malabar exercises, their growing size and scope, and their expanding geographic remit hint at the Quad’s burgeoning willingness to pursue a degree of collective security on high-end maritime security.

Malabar’s growing importance to the Quad has also been reflected in a gradual expansion of its geographic scope. Although the exercises remain true to their origins in maintaining a focus on the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal, they have recently been conducted off the coast of Guam in the Philippines Sea on three occasions (2018, 2021 and 2022), and were formally hosted by Japan in 2022 for the first time.48 Taken together, the increasingly sophisticated nature of these exercises, their growing size and scope, and their expanding geographic remit hint at the Quad’s burgeoning willingness to pursue a degree of collective security on high-end maritime security.

These developments have not happened in a vacuum. Beyond Malabar, the Quad has begun to formally explore expanded security cooperation in other defence-adjacent areas. India hosted the first Quad counter-terrorism tabletop exercises in November 2019 to share information, best practices and policy priorities, an engagement repeated most recently in October 2022.49 Such activities are useful for stress-testing national response mechanisms and revealing “interagency coordination issues” within and between Quad countries, particularly on information-sharing.50 The first Quad Strategic Intelligence Forum was convened in September 2021, immediately prior to the Leaders’ Summit in Washington, featuring the intelligence chiefs of all four countries51 in what was a striking development given India’s traditional reticence to engage deeply with Quad partners in this domain.52 Moreover, the launch of the Quad’s Indo-Pacific Maritime Domain Awareness Initiative in January 2023 — eight months after its announcement — further signals the growing willingness of all four Quad countries to work more seamlessly with each other and with key regional partners to address common maritime security risks.53

Navigating the way forward

Despite the significant progress Quad countries have made towards developing the bilateral building blocks for a collective approach to defence cooperation in the maritime domain, this effort still has a long way to go. At a practical level, the burgeoning array of cross-bracing defence agreements and maritime security activities is incomplete, poorly networked and lacking in common operational standards, particularly when it comes to certain forms of cooperation with India (see Figure 3). As the Quad’s ability to operate cohesively as a maritime deterrent is and will remain a function of the strength and compatibility of its constituent bilaterals, these Quad-minus issues must be addressed to unlock its full potential.

Figure 3. Foundational agreements between Quad members

| Information sharing | Status of forces | Logistics and sustainment | Defence industry and technology | |

| Australia-India | - | - | 2020 Mutual Logistics Support Arrangement | 2020 Defence Science and Technology Implementing Arrangement |

| Australia-Japan | 2012 Information Security Agreement (update pending); 2016 Trilateral Information Sharing Agreement; 2020 expansion of Japan’s 2015 Peace and Security Legislation | 2021 Reciprocal Access Agreement | 2010 Acquisition and Cross-Servicing Agreement (updated 2017) | 2014 Agreement Concerning the Transfer of Defence Equipment and Technology |

| Australia-United States | 1946 United Kingdom-United States of America Agreement (Five Eyes); 2016 Trilateral Information Sharing Agreement | 1963 Status of Forces Agreement; 2014 Force Posture Agreement; 2021 Expanded Force Posture Initiatives | 1989 Agreement concerning Cooperation in Defense Logistic Support; 2010 Acquisition and Cross-Servicing Agreement (ACSA; updated in 2016) | 2007 Defence Trade Cooperation Treaty (ratified in 2014); 2017 expansion of the US National Technology and Industrial Base to include Australia; 2021 Australia-United Kingdom-United States (AUKUS) Agreement |

| India-Japan | 2015 General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA); 2020 expansion of Japan’s 2015 Peace and Security Legislation | - | 2020 Acquisition and Cross-Servicing Agreement (ACSA) | 2015 Agreement Concerning the Transfer of Defence Equipment and Technology |

| India-United States | 2002 General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA); 2018 Communications Compatibility and Security Agreement; 2020 Basic Exchange and Cooperation Agreement for Geospatial Cooperation (BECA) | - | 2016 Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Agreement (LEMOA) | 2016 Designation of India as a Major Defence Partner; 2019 Industrial Security Annex (GSOMIA) |

| Japan-United States | 2007 General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA); 2016 Trilateral Information Sharing Agreement | 1960 Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan | 1996 Acquisition and Cross-Servicing Agreement (updated in 2004, 2016) | 1960 Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan; 1983 Exchange of Notes on the Transfer of Japanese Military Technology; 2016 Reciprocal Defense Procurement Memorandum of Understanding; 2022 Exchange of Notes on Cooperative Research, Development, Production and Sustainment as well as Cooperation in Testing and Evaluation |

Sources: Government of Australia, Government of Japan, Government of the United States267

This will not be straightforward. There are longstanding political sensitivities and geostrategic concerns that have traditionally impeded bilateral and multilateral efforts to advance a Quad-wide maritime security agenda. Many of these persist to this day, including different, albeit overlapping, strategic priorities, anxieties over preserving regional support for the Quad, and uneven bureaucratic and domestic political capacities for action.

Fortunately, the tides are turning. There is a growing view within the Quad that China poses a challenge to Indo-Pacific peace and stability that requires collective action and security coordination to address. While Quad countries are highly unlikely to support an explicit collective defence framework within the grouping, constraints on strengthening the cross-bracing agreements and maritime security arrangements that enable deeper operational collaboration are lessening. With a deliberate effort to consolidate, standardise and expand Quad-wide defence cooperation around key maritime security issues of mutual interest, all four Quad countries could expand their operational reach and bolster their independent and collective capacity to deter Chinese aggression.

Incomplete basis for collective action

Closing gaps in the Quad’s underlying framework of cross-bracing defence agreements is essential for enabling collective action between members. At present, the lack of reciprocal access and sophisticated intelligence-sharing agreements between India, on the one hand, and the United States, Japan and Australia on the other, is the most serious omission. Although India has hinted at developing a Reciprocal Access Agreement (RAA) with Australia, this is still under consideration and has not been matched with efforts to explore similar agreements with Japan or the United States. While the US-India Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Agreement (LEMOA) and the Japan-India Acquisition and Cross-Servicing Agreement (ACSA) create some opportunities for military access, these authorities are highly targeted, limited to logistics support and, in the case of the former, are likely subject to additional authorisation by the Indian Government in the event of a US military operation.54 An Australia-India General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA) or its equivalent is yet to be explored, notwithstanding the two countries’ relatively brisk progress on implementing a Mutual Logistics Support Agreement and their preliminary discussions on “longer-term reciprocal access arrangements” to support combined maritime surveillance operations.55 Although the United States-India Basic Exchange and Cooperation Agreement (BECA) technically permits “more specific arrangements related to sharing classified and controlled unclassified information,” it is unclear whether these have been explored at the depth required for high-end maritime security cooperation.56 Meanwhile, the reflexive “NOFORN” (Not Releasable to Foreign Nationals) classification practices within the US intelligence and export control communities, along with concerns about information protection and processing deficiencies within other Quad intelligence agencies, pose additional barriers to developing a comprehensive information- and intelligence-sharing framework.57

Where foundational agreements between Quad members have yet to reach their full potential, accelerated bilateral efforts are needed to maintain momentum towards collective defence goals. For instance, quickly finalising an update to the 2013 Australia-Japan Information Security Agreement, flagged in 2021, is crucial to advancing newly announced priorities to “develop a common foundation for optimised and agile operational cooperation” or to “strengthen exchanges of strategic assessments” and develop combined contingency responses.58 Similarly, timely efforts are required to update US-Japan alliance guidelines and intelligence-sharing procedures in order to implement the “generational” changes that Japan’s 2022 National Security Strategy has laid out for the JSDF and its ability to fight alongside US forces.59

Operationalising Quad-minus agreements, however, is often piecemeal and slow. The 2016 US-India LEMOA was debated in New Delhi for nearly a decade before signature,60 while it took eight years to translate the two sides’ shared interest in cooperation on space situational awareness from a negotiation into a 2022 Memorandum of Understanding.61 The limited implementation of these agreements has prevented Washington and New Delhi from engaging more extensively on medium-term challenges and cooperation on issues such as command and control, advanced undersea warfare, water space management, and submarine safety.62 This is a familiar story. A US-India working group established in 2018 for the implementation of the Communications, Compatibility and Security Agreement (COMCASA) has not been replicated for BECA or LEMOA,63 limiting opportunities to identify roadblocks to the full implementation of these agreements. It has also limited the development of standardised operating procedures such as guidelines that could push towards greater interoperability by stipulating the circumstances under which US vessels transiting the Indian Ocean would be refuelled by Indian vessels.64

Achieving a degree of standardisation across the Quad’s different “classes” of cross-bracing agreements will be required to develop the basis for more cohesive, routinised and unstructured forms of collective maritime action.

Achieving a degree of standardisation across the Quad’s different “classes” of cross-bracing agreements will be required to develop the basis for more cohesive, routinised and unstructured forms of collective maritime action.65 At present, all four Quad countries are exploring ways to update bilateral information- and intelligence-sharing agreements to enable more integrated maritime operations.66 This must be accompanied by regular efforts to test, refine and practice new protocols to ensure they are operationally viable and to address the qualitative differences across Quad-minus arrangements in the interests of standardising procedures to allow effective information-sharing by all four members.67 Similar dynamics apply to logistics arrangements. For instance, provisions in the Australia-India Mutual Logistics Support Arrangement (MLSA) are not specific enough to facilitate the kind of unscripted cooperation that is needed to routinise activities like the reciprocal deployment of P-8 maritime patrol aircraft outside of structured engagements.68 Nor is there enough standardisation between the MLSA, on one hand, and the US-India LEMOA and Japan-India ACSA on the other, to enable real-world trilateral or quadrilateral activities. Taken together, the preliminary state of Quad-wide protocols for information and logistics cooperation presents a real impediment to sharing sensitive data on the whereabouts of Chinese vessels across the Indo-Pacific and to collectively mounting operations to track them as part of a combined “Quad-wide” arrangement.69

Political and geostrategic constraints

Beyond technical considerations, plugging these gaps and operationalising a more collective approach to maritime deterrence and defence will require Quad countries to overcome a range of lingering political and geostrategic constraints. These include different strategic outlooks, geographic priorities, bureaucratic capacities and geopolitical risk thresholds. While these have impacted specific Quad-minus initiatives on an ad hoc basis, they have also come together in at least three cross-cutting ways to slow and constrain the overall process of developing the building blocks of a maritime security agenda.

First, Quad countries have been extremely cautious in pursuing cross-bracing or collective maritime security engagements that could be construed as part of an explicit Quad-wide defence agenda. There are many reasons for this caution. Foremost among them is that Quad countries are highly sensitive to the views of their regional partners, particularly in Southeast Asia, who fear the Quad could inflame, rather than dampen, security tensions with China.70 This is why the Quad has emphasised its “positive and practical agenda [to bring] tangible benefits to the region,” including in the maritime domain, and proceeded very slowly, if at all, on “hard security” cooperation.71 Canberra and Tokyo appear especially timid about getting ahead of Southeast Asian preferences on the Quad, possibly because each is simultaneously managing regional expectations around their respective defence strategy changes and intensifying security coordination with US forces. At a bureaucratic level, the “innate caution” of Japanese and Indian defence establishments has slowed the pace by which Tokyo and New Delhi have sought to translate shared “strategic objectives into concrete outcomes” across most Quad bilaterals.72 Australia and the United States have been mindful of driving maritime security cooperation faster than India is able or willing to proceed, or in ways that outstrip the capacity of Japanese and Indian bureaucracies to operationalise.73 While Indian political and naval leaders have grown more supportive of a robust Quad agenda in the maritime domain, they too are wary of pushing security cooperation further and faster than domestic and regional sensitivities can accommodate.74

Second, India’s status as the only non-US ally in the Quad has limited the pace and scope of security cooperation between it and its counterparts. This has been a two-way street. While New Delhi’s aversion to alliances has led it to adopt a cautious approach to advancing bilateral and multilateral defence ties within the Quad;75 Canberra, Tokyo and Washington have also been constrained by the practical complications of forging close security ties with a country that sits outside of the US alliance network. This dynamic is apparent in almost all arenas of Quad security cooperation. On reciprocal access arrangements, for example, New Delhi has been cautious about opening military facilities on the Andaman and Nicobar Islands to US and Australian forces, while Washington and Canberra have yet to grant India formal access to Diego Garcia or Darwin outside of planned military exercises. Although this has begun to change with American P-8As refuelling in Port Blair in 2020 and Indian P-8Is deploying to Darwin in 2022, a more streamlined approach to reciprocal access arrangements is needed to elevate bilateral and quadrilateral cooperation in priority areas like ASW and MDA.76 The same can be said for information-sharing. India has longstanding concerns about the fairness and reciprocity of sharing intelligence and tactical data with the United States and its allies and remains cautious about sharing information with systems that Pakistan, a US ally, may be able to access. The United States and its allies, for their part, also have longstanding technical reservations about linking secure networks with Indian military platforms based on Russian technology. Both sets of concerns have impeded Quad-minus initiatives. Although these, too, are starting to break down, it will take time and political effort to overcome engrained bureaucratic instincts on all sides.

Third, Quad countries have also been careful to balance the pursuit of collective maritime security with their own proximate interests and strategic priorities, dampening the pace and ambition of some Quad-minus initiatives. This is partly a function of their different, albeit overlapping, geographic priorities: the United States and Japan primarily focused on Northeast Asia and China’s “pacing threat” to Taiwan, Australia on its so-called “immediate region” stretching from the Northeast Indian Ocean through littoral Southeast Asia and the Southwest Pacific, and India on its land borders with China and Pakistan and wider Indian Ocean theatre.77 Until recently, different national positions on relations with China — specifically, on how much weight to place on balancing Chinese military power versus preserving economic and political ties — also slowed bilateral and Quad-wide initiatives.78 Indeed, Quad countries’ views of one another’s ties with China have played an independent role in holding back some security cooperation, particularly for initiatives in their nascent stage.

Managing constraints to move forward

While these constraints have not disappeared, many are becoming less pronounced as consensus forms within the Quad that China presents a challenge to regional stability that warrants closer collaboration on maritime security and defence cooperation.79 This does not mean all Quad-minus maritime security initiatives are achievable or that a Quad-wide collective defence agenda is on the cards. But it does create an opportunity to leverage deepening alignments, better manage enduring constraints and enhance targeted forms of defence cooperation that advance shared strategic objectives in the maritime domain.

Australia, Japan and the United States have recently begun to shed longstanding concerns about the costs and risks of operational integration in their respective defence strategy updates and new force posture initiatives.80 Although this has not foreclosed the need, especially in Australia and Japan, to prioritise specific geographic areas and avoid pre-committing military capabilities to particular crises, the easing of historic reservations about “collective security” has already created space for ambitious coordinated planning and posture arrangements.81 The March 2023 announcement of the Submarine Rotational Forces-West maritime construct is a tangible expression of what can be achieved between the United States and Australia in this less constrained environment. There is also growing potential for coordinated contingency planning through the Australia-Japan-United States trilateral, which could be leveraged to pursue collective MDA or ASW initiatives on the basis of federated areas of responsibility.

If the Quad consciously pursues a targeted approach to advancing and standardising Quad-wide defence cooperation where key maritime interests converge, it can be a force multiplier for national and collective efforts to deter Chinese aggression and strengthen regional maritime security.

India’s strategic outlook has also evolved in ways that lessen, though do not remove, barriers to deeper security cooperation with its Quad counterparts. A string of deadly incidents along the China-India border have hardened New Delhi’s view of China as a threat, deepened its sense of alignment with the Quad,82 and led it to embrace a more active maritime security posture, including an expansion of naval operations that utilise the strategically located Andaman and Nicobar Islands.83 Its growing appreciation of the need for collective action has also seen India expand its repertoire of coordinated maritime patrols, which it now conducts with France in the Western Indian Ocean and with Australia and Indonesia over the Strait of Malacca and the Andaman Sea.84 These shifts, to be sure, should not be overstated. India remains committed to strategic autonomy and “retains an enduring aversion toward participating in mutual defense.”85 This makes it highly unlikely New Delhi will join its Quad counterparts in a military crisis that does not directly affect its interests.86 Short of this high bar, however, India’s growing affinity with the Quad, coupled with its military’s intensifying focus on the maritime environment, creates opportunities for enhanced defence cooperation in specific areas of mutual interest, such as MDA, ASW and logistics support. Even in the event India stays out of a future conflict in the Western Pacific, such collaboration could enhance general deterrence, underwrite new Quad-minus operations, and make a valuable indirect contribution in a crisis.

In sum, there is a geostrategic imperative and an emerging diplomatic opportunity to operationalise the Quad as part of a more coordinated approach to maritime security and defence. This agenda, however, must work within the bounds of certain enduring, albeit lessening, national and multilateral constraints. Overall, Quad countries are likely to remain opposed to pursuing an explicit quadrilateral defence strategy for fear of losing regional support, diluting the Quad’s public goods focus, and undermining their own bureaucratic capacities and strategic preferences. But this should not prevent them from bolstering the existing network of cross-bracing agreements and maritime security arrangements to facilitate deeper operational collaboration across the Indo-Pacific. If the Quad consciously pursues a targeted approach to advancing and standardising Quad-wide defence cooperation where key maritime interests converge, it can be a force multiplier for national and collective efforts to deter Chinese aggression and strengthen regional maritime security. These areas should involve the following five shared priorities: maritime domain awareness, anti-submarine warfare, logistics, defence industrial cooperation and maritime capacity building.

Part B: Advancing a Quad-wide maritime defence agenda

Collective maritime domain awareness

Strategic rationale

The Quad requires a more networked, persistent and sophisticated approach to maritime domain awareness (MDA) as a foundation for advancing a more collaborative approach to maritime security. Although MDA cooperation is already a priority for the Quad — stemming from its members’ interests in a comprehensive and reliable MDA picture in their own priority regions — its formal MDA initiatives have so far focused on providing assistance to Indo-Pacific partners dealing with security challenges that are largely constabulary in nature. This is a critical regional “public goods” project. But the Quad and its regional partners would also benefit from a coordinated MDA agenda oriented towards higher-end military capabilities and defence challenges.

Insofar as the capacity for networked maritime domain awareness is a fundamental requirement for more complex forms of defence cooperation, developing this capability within the Quad will provide policymakers with real-time options for higher-end combined operations in the maritime domain.

As China consolidates its strategic presence across the Indo-Pacific (see Figure 4), all four Quad countries require a military-grade operational picture of its expanding deployments and maritime activities. Owing to the vast nature of the Indo-Pacific maritime environment, the difficulty in persistently monitoring PLA-N forces, the burdens of scrutinising key thoroughfares and chokepoints, and the growing capacity constraints faced by all Quad countries, there is a need for the Quad to work together on MDA. This must include deeper information-sharing, coordinated operations and collective efforts to leverage each other’s interoperable capabilities and unique posture, infrastructure and strategic geography. Insofar as the capacity for networked MDA is a fundamental requirement for more complex forms of defence cooperation, developing this capability within the Quad will provide policymakers with real-time options for higher-end combined operations in the maritime domain.87

Building a robust common operating picture will require the Quad to pursue a more networked and routinised approach to intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR), including combined operations that go beyond structured exercises and efforts to stress-test foundational access, information-sharing and logistics agreements. These lines of effort need not be quadrilateral in a literal sense. Rather, collective MDA operations should be based on a network of bilateral and trilateral arrangements — underpinned by common technical standards and protocols, and formally organised around a geographic division of labour for MDA responsibilities. If successfully developed, a more coordinated and persistent effort to track Chinese military activities across the region would signal the Quad’s capacity for collective action in the maritime domain.

State of play

Quad countries have already demonstrated a shared interest in developing a common regional MDA picture. The Indo-Pacific Maritime Domain Awareness (IPMDA) Initiative launched at the Quad Leaders’ Summit of 2022 proposed to trace “dark shipping” and “other tactical-level activities” through commercial satellite networks to deliver a “near-real-time, integrated, and cost-effective maritime domain awareness picture” to regional partners, with the first satellite array launched in January 2023.88 The IPMDA marked a step towards formalising patterns of information exchange and wider cooperation that will generate second-order benefits for a more robust collective defence agenda in future, even if the initiative itself is not defence-oriented.89 However, the information gathered through the IPMDA is unclassified and is processed and disseminated through “public goods” mechanisms like US SeaVision and regional Information Fusion Centres in the Indian Ocean, Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands,90 none of which are integrated with their counterparts.91 This means that IPMDA does not facilitate the sharing of sensitive information from military sensors, nor does it include a dedicated joint assessments component for Quad countries to evaluate shared information from an operational standpoint. While this is the right approach for delivering on the Quad’s commitment to providing information to regional countries that addresses non-traditional security challenges, it is inadequate for higher-end defence objectives. Building a common military-grade MDA picture between the four countries to effectively track PLA movements will require a dedicated, Quad-only line of effort that goes beyond leveraging commercial satellite data.

To date, it is only at the Quad-minus level that Australia, India, Japan and the United States are moving towards more collective approaches to higher-grade MDA cooperation. To be sure, Malabar exercises since 2020 have increasingly focused on building “combined air and maritime domain awareness” capacity, with maritime patrol aircraft from all four countries participating for the first time in 2022.92 But all the sophisticated MDA engagements take place at the bilateral level where various country pairings incorporate real-time information exchanges, over-the-horizon targeting, and divisions of operational and geographical labour.93 Furthermore, the foundational agreements in access, logistics, sustainment and information-sharing that provide the bureaucratic and legal foundation for turning these exercises into operations are almost exclusively bilateral (see Figure 3). These have paved the way for the deployment of an American P-8A to the Andaman and Nicobar Islands at the height of China-India tensions on the Himalayan Border in 2020,94 as well as reciprocal visits by Australian and Indian P-8s to one another’s air bases in Darwin and Goa in 2022 as part of a combined initiative to “build operational maritime domain awareness.”95 Such activities are a starting point for new forms of coordinated operations that could extend the range of national capabilities and provide more fidelity on Chinese movements through important regional chokepoints and waterways,96 leveraging platform commonality and unique geographies to maximise the strategic pay-offs of combined MDA activities.

Even so, these developments are only preliminary. Truly operationalising the Quad’s converging interests in building a more comprehensive and persistent shared MDA picture — one that is capable of tracking Chinese naval activities — will require working at another level of sophistication. Though the four countries occasionally exchange operational MDA information in the ways outlined above, this occurs on a largely ad hoc basis and at the bilateral level (and, in the case of information-sharing between India and the others, rarely in real-time).97 Moreover, when it comes to India, the nature of individual bilateral arrangements can actually have a “lowest common denominator” effect on wider cooperation among Quad partners. For instance, the absence of a US-India COMCASA prior to 2018 complicated India’s ability to share real-time tactical information not only with the United States but also with Australia and Japan, owing to those countries’ extensive use of US tactical information-sharing networks.98

Crucially, the absence of a common operating picture limits India’s capacity to engage in more complex MDA exercises and operations, including the collective tracking of Chinese naval activities by Quad maritime patrol aircraft through critical waterways.99 Even with COMCASA in place, India’s reservation over incorporating US encrypted data link hardware, like Link 16, and barriers to accessing US defence technology mean these limitations still largely apply.100 Today’s patchwork of disparate data link architectures might be “good enough” for peacetime naval cooperation, including federated maritime security patrols. But such arrangements are insufficient for developing the kind of real-time military-grade common operating picture necessary for more complex and unscripted forms of real-world cooperation between India and its three Quad partners, such as coordinated ASW operations (see next chapter).101

Recommendations

- Develop a networked and persistent approach to maritime domain awareness (MDA) as a foundation for tracking maritime activities of interest across geographic areas of responsibility, including as a baseline for potential coordinated efforts to build a comprehensive, real-time picture of Chinese military movements.

- Discuss the limitations of existing tactical data link arrangements within the Quad, and work towards an interface protocol to govern information-sharing between all Quad partners, with particular attention paid to the commonality of hardware and software or, at the least, interoperability of different tools.

Conducting sophisticated MDA operations collectively will require Quad countries to upgrade their respective information-sharing architectures. Even if the end-state of such cooperation is premised on a network of largely bilateral operations and arrangements, robust information-sharing processes will be crucial to developing the common operating picture and shared assessments on which these activities would draw. Establishing a more secure, encrypted information exchange network between the four countries will be critical. This exists between Australia, Japan and the United States, but standards of information-sharing with India remain the outlier. Facilitating such exchanges will require accelerating nascent efforts to incorporate US-origin tactical data link capabilities onto relevant Indian platforms, and/or the development of an interface protocol to determine parameters for information exchange that address Indian sensitivities around over-sharing tactical information.102 On a practical level, Quad countries should pursue solutions to these data-sharing hardware challenges with the Indian Navy that are better than “good enough” but less than seamless or perfect. - Update bilateral information security agreements and pursue a multi-party agreement to enable Quad countries to develop a more holistic picture of military activities of interest across the Indo-Pacific.

Quad countries could also update their respective bilateral information security agreements and, ideally, develop a multi-party agreement akin to the Australia-Japan-United States Trilateral Information Sharing Agreement (TISA). This agreement was signed to “enable higher capability defence exercises and operations” in the service of improving shared situational awareness across the region,103 allowing the three navies to share classified information to develop a more holistic picture of potentially hostile maritime activities, including Chinese movements in places like the South China Sea.104 Though a politically difficult proposition for India, such an arrangement would nevertheless help minimise the challenges of coordination across different bilateral information silos, and would not preclude India from moderating its participation in Quad-related MDA activities depending on political thresholds. It could also provide a multilateral basis for the hardware integration efforts outlined above. It is worth acknowledging that this kind of sharing is, ultimately, built upon a foundation of operational trust which may take some time yet to build. - Selectively integrate Quad countries’ strategically-located coastal facilities, island territories and regional access locations to conduct more persistent and coordinated MDA operations throughout the region; and jointly assess operational requirements of hosting and replenishing one another’s MDA assets.

The Quad could work towards further leveraging its members’ coastal facilities, island territories and regional access locations to conduct more persistent and coordinated MDA operations in the region,105 working within the bounds of present-day technical and political constraints. More frequent ship and aircraft visits to one another’s ports and airstrips would help to stress-test existing access, information-sharing and logistics frameworks in ways that structured exercises cannot. This would ensure that underlying agreements are fit to support a more collaborative approach to maritime surveillance underpinned by a network of region-wide staging locations.106

As a starting point, all four countries could build visits to one another’s island bases and regional access locations into existing patterns of operation.107 Bases and access locations on India’s Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Australia’s Cocos (Keeling) Islands, Japan’s Okinawan Island Chain, and US facilities in Japan, the Philippines, Diego Garcia and Guam all provide ready access for Quad ships and aircraft to extend the range and duration of patrols around key waterways and chokepoints (see Figure 1), especially if combined with robust maintenance, sustainment and overhaul complexes. In operational terms, India and Australia could expand their current maritime domain awareness initiative to conduct reciprocal visits and coordinated patrols in the Northeastern Indian Ocean.108 Japanese P-3C Orion or Kawasaki P-1 could similarly take advantage of these locations to conduct coordinated or joint operations with Australian and Indian counterparts en route to or on return from rotational deployments to JSDF Base Djibouti or following deployments to the South China Sea.109 In the Western Pacific, Australia, Japan, and the United States could expand the scope, duration and sophistication of “interchangeable” patrols in littoral Southeast Asia and the Pacific by leveraging ports and airstrips in northern Australia, Singapore, the Philippines, Guam and Japan’s southern islands. - Set up formal MDA and ISR initiatives that combine shared access, information-sharing and analysis, and platform interoperability to create a common operating picture within geographically-defined Quad groupings, including by incorporating common UAV platforms.

Finally, Quad countries should pursue more formalised MDA and ISR initiatives that sit at the intersection of shared access, information-sharing and analysis, and platform interoperability. The new US-Japan Bilateral Intelligence Analysis Cell, which is designed to enable American and Japanese personnel to “jointly analyse and process information gathered from assets of both countries,” provides a useful template for how this might work.110 This initiative involves ISR missions over the East China Sea by American MQ-9 Reaper and SeaGuardian UAVs taking off from Kanoya Air Base, Japan,111 with the JASDF set to integrate its own drones in the operations in the coming year.112 Exploring similar arrangements within the Australia-India Maritime Surveillance Initiative, US-India MDA cooperation in the Indian Ocean, or Australia-Japan-United States ISR operations in the South China Sea would be a logical step, particularly as greater numbers of UAVs are acquired by all four countries.113 Focusing on joint analysis rather than joint contingency planning would allow for a common understanding of threats and challenges,114 and could offset some of the technical difficulties of real-time information sharing. Such initiatives would require revising existing access agreements and inking new Status of Forces agreements, which have been raised in the Australia-India context115 but may not be politically feasible between all four partners at this time.

Coordinated anti-submarine warfare operations

Strategic rationale

Developing the capabilities for coordinated anti-submarine warfare (ASW) should be a priority maritime security task for the Quad. China’s increasingly large and sophisticated fleet of attack submarines (see Figure 6) is expected to number between 65 and 70 boats throughout the 2020s and could present a major challenge to freedom of access throughout the Indo-Pacific in a contingency.116 Although China is still modernising its underwater capabilities, the rapid expansion of its submarine-related activities is of great concern to all four Quad nations (see Figure 4). The United States has tracked Chinese oceanographic vessels conducting seabed mapping operations in the waters around US bases in Guam and Hawaii, operations which lay the navigational groundwork for submarine deployments.117 India is grappling with the PLA-N’s growing submarine footprint in the Indian Ocean, as well as with Chinese seabed mapping operations observed around strategic waterways in the Eastern Indian Ocean.118 Japan faces regular Chinese submarine activity along its island chains, including in the East China Sea.119 Recent incidents between the PLA-N and Australian ships and aircraft in the Arafura and South China Seas have highlighted the growing assertiveness of Chinese submarine operations, with concerns rising in Canberra regarding PLA-N submarines and unmanned undersea vehicles (UUVs) operating in Australia’s northern approaches.120

Figure 4. Snapshot of select Chinese maritime access and activities in the Indo-Pacific

| Map reference | Date | Location | Activity | Involved capability | Description |

| 1 | November 2014 | Sri Lanka | Docking | Submarine | Submarine Changzheng-2 docked at port in Colombo for five days for refuelling and crew refreshment, despite warnings that any docking of a Chinese submarine would be unacceptable to India. |

| 2 | November 2015 | Japan | Encounter | Submarine | A Chinese submarine stalked USS Ronald Reagan on its way from Yokosuka Naval Base in Japan’s Kanagawa Prefecture to the Sea of Japan, reportedly for ‘targeting practice.’ |

| 3 | May 2017 | Pakistan | Docking | Submarine | Type 091 submarine Han-class nuclear-powered submarine docks in Karachi harbour. |

| 4 | January 2018 | Senkaku Islands | Operations | Submarine | Chinese frigate and unidentified submarine entered contiguous zone around the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands. |

| 5 | September 2019 | Indian Ocean | Encounter | Vessel | Shiyan-1, or Experiment 1, found carrying out research activities inside the Indian EEZ without permission, and was expelled by the Indian Navy. |

| 6 | December 2019 | Indian Ocean | Operations | Unmanned underwater vehicle | China deployed a fleet of underwater drones in the Indian Ocean, making more than 3,400 observtions between December and February. |

| 7 | December 2020 | Indonesia | Encounter | Unmanned underwater vehicle | Indonesian fishermen found an underwater drone closely related to the Chinese Sea Wing family. |

| 8 | January 2021 | Indonesia | Operations | Vessel | Survey ship caught ‘running dark’ proximate to Lombok Strait and Indonesia’s Natuna Islands. |

| 9 | January 2021 | Indian Ocean | Operations | Vessel | Chinese survey ship, the Xiang Yang Hong 03 operating in the Indian Ocean to map the seabed across vast swath of the Indian Ocean. Accused of ‘running dark’ in Indonesian territorial waters. |

| 10 | December 2021 | Malacca Strait | Chokepoint operations | Submarine | Chinese submarine entered the Malacca Strait and pulled into the Yangon River, Myanmar. It was subsequently sold or transferred to Myanmar Navy. |

| 11 | December 2021 | Palau | Operations | Vessel | A Chinese government survey ship, Da Yang Hao, has been accused of illegal activities in Palau’s waters. |

| 12 | July 2022 | South China Sea | Encounter | Submarine | Australian HMAS Parramatta followed by a Chinese nuclear-powered submarine, a warship and multiple aircraft. |

| 13 | August 2022 | Sri Lanka | Docking | Vessel | Research and space-tracking vessel Yuan Wang-5 docked in Hambantota for six days. |

| 14 | December 2022 | Indian Ocean | Operations | Vessel | PLA ballistic missile, satellite tracking and seabed mapping ship Yuan Wang 5 entered the Indian Ocean Region on December 5 and exited through Sahul Banks, north-west of Australia, on December 12 apparently on a mission to track Chinese space activity. The frequent mapping of the Sunda and Lombok Straits indicates that the PLAN Is planning future submarines operations in the Indian Ocean. |

Sources: ABC News, The Diplomat, Forbes, Naval News, Nikkei Asia, South China Morning Post, The Economic Times, The Hindustan Times, The Times of India, USNI News268

Against this backdrop, the Quad should work towards developing a collective capacity to track Chinese submarines across geographically defined areas of responsibility for better awareness.121 As with collective MDA efforts, such an approach would see Quad militaries share and “hand off” monitoring and surveillance responsibilities with their counterparts on a more consistent and structured basis than in the past.122 This kind of cooperation is not without precedent. The United States and Japan pursued a federated approach to ASW during the Cold War as part of their collective efforts to check Soviet submarine activities in Northeast Asia, an arrangement that included the allocation of roles and responsibilities for chokepoint security and SLOC protection, and which, in turn, informed bilateral force structure planning and decision-making.123 Today, there is growing support in Australia, Japan and the United States for a more federated approach to regional ASW and strong interest in this agenda among some Indian strategists.124 But enabling the Quad to operate at high levels of integration will not be easy. A collective ASW framework that harnesses the Quad’s capacity, capability and access locations will require sharing sensitive mission and tactical data, combined operational planning, more sophisticated exercises, new access arrangements, and coordinated and routinised ASW patrols across the region.125

State of play