The announcement of the Australia, United Kingdom and United States (AUKUS) security partnership on 16 September 2021 transformed Australia’s perceptions of its capacity, capability and the role of its oldest allies. Few announcements to date have inspired as much interest, and as much misunderstanding, as AUKUS has. At this milestone anniversary, it is essential to revisit what we have learnt so far, what progress has been made, what challenges remain and what lies ahead for this extraordinary partnership.

What have we learnt about AUKUS in its first year?

Since the last United States Studies Centre (USSC) explainer on AUKUS, written at the time of its announcement, the true character and implications of the agreement have been further clarified. The security partnership is comprised of two pillars: to deliver Australia a fleet of conventionally armed submarines and to collaborate on a host of advanced capabilities. On the whole, it is apparent that AUKUS marks a 'pivot point' in the underlying nature of Australia’s bilateral alliance with the United States which had been based upon US military primacy and global influence. At its core, the partnership recognises the strategic environment in the Indo-Pacific demands a more collaborative and integrated approach to deterrence that leverages the combined defence technology and industrial bases of all three countries.

It is now evident that the shared resolve of the three nations’ leaders has been the enabling element overturning decades of established conventions in alliance collaboration, most significantly around the sharing of nuclear propulsion technology.

It is now evident that the shared resolve of the three nations’ leaders has been the enabling element overturning decades of established conventions in alliance collaboration, most significantly around the sharing of nuclear propulsion technology. While the current focus is on delivering results on both pillars of cooperation trilaterally, there may also be opportunities to involve other allies and partners like Japan or New Zealand on specific projects in the future.

Nuclear propulsion, not nuclear weapons

Throughout the past year, officials from all three countries have been at pains to dispel both regional misunderstandings and disinformation from adversaries about what AUKUS is and is not. Most importantly, AUKUS will not enable Australia to acquire nuclear weapons, nor does Australia want them. Australia is entitled to operate submarines powered by nuclear propulsion under the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT). As the first state without nuclear weapons to acquire this capability, Australia and its AUKUS partners have set out additional measures ensuring compliance with International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) safeguards, including prohibiting uranium enrichment, using welded power units, instituting verification processes and implementing additional safeguards to prevent any diversion of nuclear material.

A new collaboration, not a new alliance

Contrary to much international reporting, AUKUS is not a new alliance. It is not a collective defence treaty, and it does not supersede Australia's 1951 ANZUS Treaty with the United States or Australia's strategic partnership with the United Kingdom. Cooperation under AUKUS is distinct from Australia's bilateral Enhanced Force Posture Initiatives with the United States.

A partnership, not an arms deal

It is also clear that AUKUS is not simply an ‘arms deal’ for submarine acquisition. Initially overshadowed by the submarine announcement, the advanced capabilities pillar of the partnership has developed in scale and ambition, with eight priority areas for collaboration that will be the key to enhancing collective deterrent capabilities in the immediate term.

What has AUKUS accomplished so far?

Bureaucratic settings

Over the last year, the three countries worked to have their bureaucratic settings right for the delivery of capabilities. The hard work of implementation is far from limited to senior officials. Beyond the trilateral governance structure formed by the AUKUS Joint Steering Groups and the 17 working groups, each government has made arrangements nationally to steer progress.

For Australia, AUKUS is a whole-of-government venture. All federal departments with a foreign portfolio have assumed specialised responsibilities during the 18-month scoping period.

In the United States, National Security Council AUKUS Coordinator James N. Miller directs interagency efforts from the White House. At the Department of Defense, Abraham Denmark serves as Senior Advisor for AUKUS and is tasked to lead the submarine effort together with Rear Admiral Dave Goggins.

In the United Kingdom, specific roles have been carved out within the Ministry of Defence with responsibility for AUKUS delivery, though no further information has been made publicly available.

For Australia, AUKUS is a whole-of-government venture. All federal departments with a foreign portfolio have assumed specialised responsibilities during the 18-month scoping period:

- A multi-agency Nuclear-Powered Submarine Task Force led by Rear Admiral Jonathan Mead was stood up, with responsibility for consolidating information on the pathway to nuclear-powered submarines and ensuring compliance with the requirements of nuclear stewardship;

- The Department of Defence prioritises capability delivery;

- The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade manages regional messaging and non-proliferation legal compliance; and

- The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet supports the prime minister, builds social license, and leverages the heft of government when called upon.

Legal and personnel regulations

Important steps have also been made toward cross-national legal and personnel regulations. A key milestone in preparing for the nuclear-powered submarine program was the Exchange of Naval Nuclear Propulsion Information Agreement in February 2022. The record pace at which the agreement was finalised in all three countries, only three months from signing to entry into force, reflects the high priority the three governments have assigned to AUKUS implementation.

Australia and the United Kingdom established a submariner training program in September 2022, where Australian naval officers will train aboard the HMS Anson and four other Astute-class nuclear-powered submarines for the first time. Similarly, a new bipartisan Australia-US Submarine Officer Pipeline Act was also introduced to the US Congress. These initiatives suggest that a suite of similar training and labour mobility programs might be created to share key expertise with Australia.

Infrastructure

The former Morrison government announced a series of investments to prepare Australia’s military infrastructure for the delivery of AUKUS capabilities. The most significant of these ventures was the announcement of the construction of a “Future Navy Base” on Australia’s east coast at either Port Kembla, Newcastle or Brisbane. In addition, the government announced that the Osborne Shipyard in Adelaide would be tripled in size through adjacent land purchases for future shipbuilding work. It also committed to a $1 billion investment in upgrades to the Australian Navy’s submarine fleet home port at HMAS Stirling in Perth to support the stationing of a nuclear-powered submarine in Australian waters, as well as $4.3 billion for a large-vessel dry berth in Western Australia that will support the maintenance and sustainment of nuclear-powered submarines.

Advanced capabilities

Progress has been made in accelerating deliverables under the advanced capabilities pillar. In April 2022, the three leaders committed to four new streams of cooperation on hypersonics and counter-hypersonics, electronic warfare capabilities, information-sharing and defence innovation. This announcement doubled the initial four lines of effort on undersea capabilities, quantum technologies, artificial intelligence and advanced cyber set out in September 2021. As a recent USSC report noted, each advanced capability stream is at a different stage of maturity, meaning different timelines for delivery. The most progress to date has been in undersea capabilities, which will see trials of autonomous underwater vehicles commence in 2023, as well as cooperation on quantum technologies, including on position navigation and timing devices. In addition, accelerated near-term progress on the hypersonics and cyber streams was agreed upon at the July meeting of the Joint Steering Group for Advanced Capabilities.

Table 1. Progress on AUKUS advanced capabilities stream

|

Advanced capability |

Date introduced |

AUKUS priorities |

Related Australian initiatives |

|

Undersea capabilities |

2021 |

Autonomous underwater vehicles, under AUKUS Undersea Robotics Autonomous Systems (AURAS). Trials commencing in 2023. |

Devil Ray T38 Unmanned Surface Vessels, Ocius Bluebottle Unmanned Surface Vessels |

|

Quantum technologies |

2021 |

Quantum technologies for positioning, navigation, and timing, under AUKUS Quantum Arrangement (AQuA). Trials commencing over next three years. |

Australia-US Quantum Technology Cooperation Agreement Quad’s future focus on quantum technologies |

|

Artificial intelligence and autonomy |

2021 |

Adoption and improved resilience of autonomous and AI-enabled systems. |

Defence Innovation Hub grants program |

|

Advanced Cyber |

2021 |

Critical communications and operations systems. Accelerated progress at July 31 Joint Steering Group meeting. |

Australian Signals Directorate (ASD) REDSPICE program Australia-UK Cyber and Critical Technology Partnership |

|

Hypersonic and counter-hypersonic capabilities |

2022 |

Accelerated progress at July 31 Joint Steering Group meeting. |

RAAF-US Air Force Southern Cross Integrated Flight Research Experiment (SCIFiRE) DSG-US Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) Hypersonic International Flight Research Experimentation (HIFiRE) |

|

Electronic warfare |

2022 |

Tools, techniques, and technology on electromagnetic spectrum. |

Five Eyes intelligence sharing partnership work on signals intelligence |

|

Innovation

|

2022 |

Defense innovation enterprise and integration of commercial technologies. |

DSTG Science, Technology and Research (STaR) Shots |

|

Information sharing |

2022 |

Inter-agency trilateral cooperation and workstreams |

Five Eyes intelligence sharing partnership |

Sources: “FACT SHEET: Implementation of the Australia – United Kingdom – United States Partnership (AUKUS),” 5 April 2022; “Readout of AUKUS Joint Steering Group Meetings,” 31 July 2022; Jennifer Jackett, “Laying the foundations for AUKUS: Strengthening Australia’s high-tech ecosystem in support of advanced capabilities,” United States Studies Centre at the University of Sydney, July 2022.

What have been the challenges?

Cancelling the French deal

Many of the challenges arising during AUKUS’ first year will persist into the future. The first challenge to AUKUS implementation, dominating initial public reactions, was the French response to the cancellation of the Attack-class submarine program. The financial compensation for the cancellation of this program, $835 million for France’s Naval Group, has since been resolved and the Albanese government has repaired diplomatic relations with France through visits to Paris by Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and Deputy Prime Minister and Defence Minister Richard Marles. Though the first challenge of French outrage may be resolved, questions of cost endure. The total spend on the cancelled program over the last decade stands at $3.4 billion, and the closest this program came to building a submarine was the 1:72 scale model produced for the project.

Addressing proliferation concerns

Proliferation concerns remain widespread at home and abroad. Domestically, the Australian Greens Party oppose the acquisition of nuclear-powered submarines, what they have called “floating Chernobyls,” while crossbench independents remain ambivalent about AUKUS. In opposition, the Peter Dutton-led Coalition have begun to revisit the question of civil nuclear power generation to manage energy prices, adding an additional layer of complexity to the domestic debate.

Non-proliferation experts have identified legitimate risks of fuelling arms racing behaviours and increasing threat perceptions associated with Australia’s acquisition of Tomahawk cruise missiles for the future submarines. In the United States, members of the left wing of the Democratic Party have flagged concerns about potential proliferation precedents. This high-level unease places the onus on Australia to consistently demonstrate its nuclear stewardship credentials.

Countering misunderstanding and misinformation

Messaging to the region around Australia’s dedication to non-proliferation has been disrupted by ongoing misinformation campaigns. China and Russia have made a concerted effort to undermine AUKUS in international bodies. China, for instance, requested forming a 'special committee' in the IAEA to investigate AUKUS’ compliance. Indonesia and Malaysia continue to express concerns about the use of highly enriched uranium under AUKUS.

Keeping the public regularly informed will be necessary to counter disinformation and avoid turning AUKUS into an initiative that polarises the public along party lines, as early public opinion polling suggests is already occurring.

The public narrative around AUKUS has suffered from sporadic leadership communication. Following the initial 12-minute press conference on 16 September 2021, one leaders' level statement and a readout of the Joint Steering Group Meetings in July 2022 represent the sum total of dedicated, high-level communication. In Australia, no statement to Parliament has been made by the prime minister or minister for defence of the previous or current governments, as done previously in relation to other Australia-US activities such as the Joint Facilities. Keeping the public regularly informed will be necessary to counter disinformation and avoid turning AUKUS into an initiative that polarises the public along party lines, as early public opinion polling suggests is already occurring.

Preserving Australia’s sovereignty

Much of the domestic criticism of AUKUS has focused on how the arrangement might diminish Australia’s strategic autonomy. The government must show that AUKUS does not pre-emptively commit Australia to future military contingencies and that, as US Secretary of State Antony Blinken said last year, “there are no follow-on reciprocal requirements of any kind.” Deputy Prime Minister Marles’ desire to bring forward the submarine acquisition timeline a decade earlier must similarly be reconciled with repeated promises that the submarines will be built in Adelaide.

Funding the venture

Among the most significant ongoing concerns for AUKUS governments are the daunting resourcing challenges. This begins with financing eight nuclear-powered submarines, which could cost anywhere from $116 billion to $171 billion in out-turned dollars depending on chosen build, if built in Adelaide. Australian Treasurer Jim Chalmers has already painted a bleak picture of a trillion dollars in national debt and rising inflation and interest rates. The October Federal Budget will need to locate funding for both the submarines and the suite of advanced technologies, for which there has been no AUKUS-specific costing to date.

Resourcing AUKUS also means training the workforce that will build and operate these capabilities. It will require cultivating what the Chief of the Nuclear-Powered Submarine Taskforce, Vice Admiral Jonathan Mead, has called a “nuclear mindset” to become the technical stewards of this endeavour. Strengthening Australia’s science, technology and defence industry ecosystem, as well as putting in place a pathway for advanced skills training, will be priorities.

What lies ahead for AUKUS?

Taskforce and review outcomes

The next year will be pivotal as the three countries move from the consultation phase to the implementation of the AUKUS partnership. The Nuclear-Powered Submarine Taskforce will deliver its recommendations to Government in March 2023. This will determine whether Australia will go with the British Astute-class, the American Virginia-class nuclear submarines, or some new version shared by all three countries. The outcomes of the initial consultation period should also clarify the details of a domestic build, the Australian Government’s proposed interim capability, and further initiatives to fill the workforce demands of AUKUS. The Australian Government’s Defence Strategic Review, to be released in early 2023, will articulate how AUKUS fits into Australia’s broader defence posture, preparedness and structure.

The outcomes of the initial 18-month consultation period should clarify the details of a domestic build, the Australian Government’s proposed interim capability, and further initiatives to fill the workforce demands of AUKUS.

Developing the trilateral architecture

All three governments will also be working towards clarifying the organisational responsibilities and funding allocation for implementation. Some of the AUKUS advanced capabilities such as cyber security and innovation cut across different parts of the defence and wider national security bureaucracy. Avoiding the bureaucratic turf wars that often accompany major policy initiatives will be a priority. In addition, the Australia-UK FTA, which will inform arrangements to boost the supply of skills and the defence industrial base to support AUKUS, is expected to receive parliamentary approval in 2023.

Reforming and updating export controls

Importantly, the three countries will need to enhance defence industrial collaboration to facilitate the above efforts. Australia’s defence industrial base has historically depended on the United States for key technologies and enablers, and AUKUS will be no different. Minister for Defence Industry Pat Conroy promised to engage Australian industry partners on AUKUS in early 2023. At the core of this will be improving the US National Technology and Industrial Base, which is designed to foster a defence free-trade area among some US alliance partners, as well as leverage the Australia-US Defence Trade Cooperation Treaty.

In a July 2022 speech, Deputy Prime Minister Marles emphasised his priority was to “streamline processes and overcome barriers” in industrial collaboration. To do so, the Australian Government will have to learn to better navigate the complex US defence export control regime, especially the US State Department’s International Traffic in Arms Regulations with its onerous restrictions on security classification and technology transfers. This will demand close coordination with the US Congress and US agencies, such as the US Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration on the submarines and the Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security on Export Administration Regulations for areas like quantum technologies.

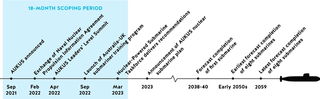

AUKUS timeline

Conclusion

Australia has embarked on an ambitious, long-term project to secure itself in an increasingly uncertain security environment. If AUKUS were to fail, the impact on Australia’s capability and credibility would be vast. Regardless of any ongoing reservations about the nature and implications of AUKUS, one year in the three governments are firmly committed and need this arrangement to deliver.

Given their scale, both pillars of AUKUS require a whole-of-nation effort now and far into the future. Progress on the implementation of key AUKUS initiatives over the past 12 months gives new gravitas to this monumental security arrangement and has effectively laid the foundations for the significant task ahead. The consultation and scoping phase of AUKUS now moves into the implementation phase. How the Albanese government responds to the recommendations of the Nuclear-Powered Submarine Taskforce and the Defence Strategic Review in early 2023 will dictate the options for successive governments to come.

Ambiguities endure as to AUKUS’ scope, cost, timeline and meaning. The challenges and concerns identified in this explainer require hard work. But they must be overcome to advance Australia’s strategic interests. The race has now well and truly begun. AUKUS will be a marathon, not a sprint. Setting down some key markers and achieving tangible outcomes in 2023 will be critical. Otherwise, AUKUS could quickly fall off the pace.