Good morning, everyone. I’m Rui Matsukawa.

Thank you for the kind introduction. I've known Mike [Green] for almost 20 years, since my days in Washington DC, where I was sent by the [Japanese] Foreign Ministry to Georgetown University, and you were at the SAIS. So, it's a great pleasure to be here.

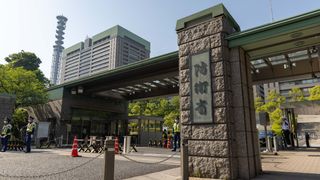

Japan’s new defence policy

I've been working with the Japanese defence industry for a couple of years, and, as you may know, the Japanese Government changed the fundamental position on its defence policy in last year's National Security Strategy. In summary, the Strategy covers a variety of areas from the defence industry and defence equipment transfer to the position of long-range missiles, and the development of new technologies to enhance its capacity in new domains, cyber, space and these new technologies. So, it has a wide range of coverage.

In short, Japan decided to defend our nation by ourself. Of course, it does not mean we cut off the Japan-US Alliance: it remains the most important alliance. Rather, we want to further strengthen the alliance and collaborate with Australia, India, the United Kingdom, and other countries. We want to have more security partnerships with like-minded countries which share our strategic interests and values.

Why does defence equipment transfer matter?

Defence equipment transfer is one of the most important, in my opinion, pillars for changing Japan’s position to a more proactive defence policy.

1. The Japanese defence industry needs more customers

It’s well-known that Japan has been taking a very conservative, or rather, I would say, isolated policy when it comes to defence industry. The Japanese defence industry has served only the needs of the Japan Self-Defense Forces (SDF) for the last 70 years. In other words, the customer of our defence industry is one: the Japan Self-Defense Forces.

So, considering that our defence budget had been flat – within one per cent of GDP – over that period, and that foreign equipment for platforms such as F-35 is really costly, the budget available for the domestic defence industry had been shrinking. And when you have only one customer, it’s not a surprise that Japan’s domestic defence industry has suffered. Quite a few large to small companies have withdrawn from defence industry. This cannot be sustained.

2. Defence equipment transfer can strengthen security partnerships

The other thing to consider is the role of defence equipment transfer in strengthening strategic partnerships. You can see this in India's posture vis-à-vis Russia. India has historically purchased much of its defence equipment from Russia. That is why India has not been able to take on a very clear position regarding Russia’s aggression in Ukraine. This suggests that, if you have defence industry corporation, you can deepen alliances and partnerships. In other words, defence equipment transfer can be a very effective tool for strengthening the relationship with the country to which you transfer equipment.

To date, there is only one case where Japanese industry has been able to successfully export defence equipment, that being coastal radar systems to the Philippines. If the Philippines purchases more radars, or perhaps even frigates from Japan, then Japan-Philippines defence cooperation will be much deeper. Such relationships are not easily cut off once they begin, which means that if you have someone or some country with which you would really like to deepen your relationship, defence equipment transfer is a very effective tool for strengthening defence cooperation.

So, with these two points in mind, the Japanese Government (GOJ) has changed its policy on defence equipment transfer to a much more proactive position. The GOJ has decided to be more responsible as a nation with exports from our defence industry, including equipment like frigates, radars, and many other things. Exports of defence equipment is restricted severely, only allowing five categories of not offensive weaponries.

The guidelines need to be updated

There were some hindrances for the Japanese defence industry, which prevented it from being able to export. Here, I am referring to the Implementation Guidelines for the Three Principles on Transfer of Defense Equipment and Technology (the guidelines). Historically, Japan has approached defence equipment transfer in a very limited way.

The only instances in which these restrictions do not apply is to co-researched and co-developed projects. For instance, right now, Japan is developing a next generation jet fighter (F-X) with the United Kingdom and Italy, and because it is a co-researched and co-developed ‘no-offensive weaponry’, the restrictions are not applied.

But, when it comes to just a pure export of Japanese industry products ―let’s say, Japan would like to export radars to Indonesia or frigates to Vietnam – you have to follow the guidelines. These restrict acceptable exports to only five categories: rescue, transportation, vigilance, surveillance, or minesweeping. Defence articles proposed for export must fit within these parameters. Otherwise, they are not valid for export.

So, that is the restriction. This is made more complicated when you consider international markets, where every country is competing for export opportunities. Japan can't really compete with its current restrictions. Well, let's think about it. Suppose that you go grocery shopping, and the store only sells carrots, broccoli, cabbages, tomatoes, and bananas. Well, if you can buy only five items, or five vegetables at the grocery, do you want to go to this shop? So, that is the situation.

The current progress (as of 10 October 2023)

The GOJ has decided to loosen these guidelines. Revisions are now under discussion between our party, the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), and our partner Komeito, which is historically a more peace-minded and peace-oriented party. In my opinion, defence equipment transfer definitely serves to strengthen the relationship with the countries that Japan needs to cooperate with. So, in my opinion, we have to abolish the existing export categories. The deliberation between the LDP and Komeito on this issue may be finalised by the end of this year. We'll see. But the bottom line is ― there is a consensus that we have to loosen these guidelines. To what extent is the question.

The other thing I would like to also touch upon is the other developments with regards to Japan’s defence equipment transfer and defence industries development.

New fund for the defence industry

New legislation to establish a fund for strengthening defence industrial bases was just implemented on October the first, about one week ago. This fund is budgeted at 40 billion yen per year, and roughly speaking, we are thinking about a five year timeframe, which means about 200 billion yen is available for industry to make necessary modifications to defence equipment for export to foreign countries, as I explained.

At present, Japanese defence industry only thinks about servicing the Japan Self-Defense Forces. Let’s say, you make a submarine, which is a highly sophisticated platform used only by the Japan Self-Defense Forces. If you want to export such a platform, you can't really export the model with the highest specifications, as these are only considered for use by our own country.

So, you have to have a modification for lesser versions, the type of the equipment which you feel comfortable to sell to the other countries, even to the partners. Full-specification platforms are also really expensive, and we have to offer more reasonable prices for Japanese equipment to be competitive. So, this fund is aiming at Japanese industry, our companies, to make necessary modifications for sales to other countries. That is an effort which has already been implemented.

Conversion from non-interfering to more responsible government

So far, for about 70 years, neither the Japanese industry nor GOJ has previously thought about exporting. That is the situation. The present guidelines were modified, but are still really restricted. The 2013 guidelines, which is the present guideline, was modified to allow export with a limited manner under Prime Minister Abe.

The GOJ’s posture then might be ‘okay, Japanese companies, if you want, you can export.’ That was the posture, but it was not enough to make the exports possible. There was no proactive rule or involvement from the GOJ. That's a reason why there is only one successful case for that transfer to date, the radar to the Philippines.

So, the GOJ has decided to take the responsibility. What I mean is that the government will be the frontrunner for making exports possible. The GOJ is now trying to enhance the availability of personnel for the departments which are in charge of exports and transfers, especially the Acquisition, Technology, & Logistics Agency (ATLA). However, the final [government] organisation has not really been decided here. We are still under deliberation regarding what will be the most desirable government organisation for making this transfer more effective. We need a commander, so to speak, for the equipment transfer at the government level.

And lastly, the defense equipment transfer support fund has also been established to support the defence industry for upgrading technology, strengthening security, and other requirements. To date, the GOJ has been very active in supporting our small and medium sized ‘ordinary’ industries, but when it comes to defence industry, there have been no subsidies whatsoever to support them when they want to upgrade their technologies, or enhance their businesses in other ways. Now, the GOJ has decided to support the defence industry for strengthening technology, security, and all of that. The GOJ is very serious about enhancing our difference industry, and revising the defence equipment transfer guidelines for arms exports.

Thank you.