As severe winter weather hit Texas late last month, residents suffered the loss of electricity and water, and dozens of people died — from exposure, from house fires, from carbon monoxide poisoning. At the height of the crisis, forty-five hospitals in southeast Texas declared an “internal disaster” to stop emergency vehicles from bringing them patients.

Even as the weather has warmed up and electricity has come on, residents face sizeable challenges. Many had to boil water for several days after low pressure made it unsafe to drink. Homes were badly damaged due to burst pipes; plumbers are in high demand and struggle to source supplies. In early March, thousands in Houston — the nation’s fourth largest city — still did not have water.

The crisis that has left some four million Texans without electricity involved a weather pattern that affected many other parts of the United States — and resulted in deaths elsewhere, too — but Texas has garnered much of the attention because it has, for the last two decades, been conducting an extensive experiment in electrical deregulation wherein the entire electricity delivery system is left to a market-based system of generators, transmission companies, and retailers. Much of the attention has focused on a particular non-profit organisation called the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT). That organisation had planned to rotate outages around the state, but demand quickly overwhelmed the power grid, and they were not able to do so.

Texas has garnered much of the attention from the crisis because it has, for the last two decades, been conducting an extensive experiment in electrical deregulation wherein the entire electricity delivery system is left to a market-based system of generators, transmission companies, and retailers.

The family of eleven-year-old Cristian Pavon Pineda of Conroe, Texas, has filed a US$1 million lawsuit against both the power company Entergy and ERCOT. The boy’s mother found him unresponsive in bed, and while the autopsy has yet to confirm the cause of death, his family understands he died of hypothermia. The lawsuit alleges the company, as well as the non-profit council, put “profits over the welfare of people” and failed to prepare for the emergency, especially in its neglect of those most vulnerable to the cold. Attorney for Pineda’s family, Tony Buzbee, is also representing six other families who lost loved ones in the disaster in Texas.

While freezing temperatures are unusual, for most Texans, this cold snap was not the first they experienced in their lifetimes. Following the winter weather that hit Texas in February 2011, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission and the North American Reliability Corporation published a report which found that the generators had failed to prepare for winter. The report made several recommendations to prevent a repeat of the “spotty generator performance”. Many are now asking why the power companies did not do more in the intervening decade to follow the given advice.

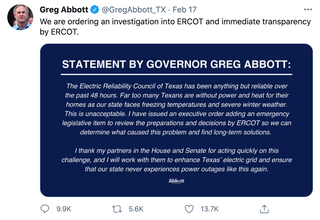

As Texans send pictures of water-damaged homes to insurance companies, and Governor Greg Abbott launches an investigation into ERCOT for its handling of the crisis, one wonders what regulatory changes might be forthcoming? Will local, state, or federal government policy shift to regulate the companies to protect residents?

One way to address the question is to consider what has prompted governments to bring about major regulatory changes in the past. In 1906 Congress passed the Pure Food and Drugs Act, which authorised the formation of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). This organisation, students of US history and literature often learn, came into being partly as a response to the publication of “muckraker” Upton Sinclair’s book The Jungle. After months of labouring alongside packinghouse workers and covertly observing the operations, Sinclair wrote the best-selling novel depicting gruesome practices in Chicago meat-packing plants. President Theodore Roosevelt himself read the book and then authorised the federal inspection of abattoirs. Sinclair did not think these inspections would yield reliable evidence and wrote to Roosevelt expressing his doubts that federal inspectors would see much beyond the “smooth pretences” of the packing plant managers.

While connecting the book’s impact to the 1906 legislation makes some sense, the FDA does not owe its existence to one popular story about Bohemian immigrants in Chicago. The legislation was the culmination of about a hundred bills and twenty-five years of work to regulate consumer goods. Many advocates, including Harvey Washington Wiley, chief chemist at the Bureau of Chemistry at the US Department of Agriculture, pushed tirelessly for this legislation.

To take a different Gilded Age example, the town of Johnstown, Pennsylvania, experienced a devastating flood in 1889. More than two thousand people lost their lives when, after heavy rainfall, the South Fork dam liquified and blew out the earthen structure, sending a twenty million tonne torrent of railroad components, debris, and water down into the valley. Rainfall alone, however, did not cause the disaster any more than the weather alone caused the crisis in Texas. The dam belonged to the South Fork Fishing Club — an elite recreation association of Pittsburgh’s richest industrialists, including Andrew Carnegie and Henry Clay Frick. Shoddy repairs over the years, as well as modifications to the original dam design to decrease the capacity of the emergency spillway, contributed to the flood in such ways that the Association of State Dam Safety officials called it the worst man-made disaster in the United States, prior to 11 September 2001.

The American Society of Civil Engineers conducted an investigation, which concluded that alterations to the structure led to the dam’s overtopping, but, as geophysicist Neil Coleman points out, the report was sanitised in ways that ensured the dam’s owners were not liable. Several Johnstown families filed lawsuits, all of which played out in Pittsburgh courtrooms where all-male juries consisted of employees of the powerful industrialists who owned and operated the South Fork Fishing Club. All of the lawsuits filed against the club failed.

But the town flooded again in March 1936. This flood, which took the lives of twenty-five people, occurred in the middle of the New Deal — a time of remarkable legislative productivity. Local people then flooded President Roosevelt’s desk with 15,000 letters asking that the state take action. Local newspapers in Johnstown demanded federal help. Congress passed Flood Control Acts in that year and the years that followed, culminating with the omnibus Flood Control Act of 1939 which authorised flood control projects across the United States and transferred ownership of local and state dams to the US Army Corps of Engineers.

Even with pending lawsuits, investigations, and a moratorium on electricity disconnections for non-payment, it is hard to detect much appetite for regulation among Texas politicians.

A component of the New Deal that provides important context for the Flood Control Acts was the Tennessee Valley Authority Act (TVA). It established a massive resource planning project that covered an area the size of England and created a huge public power company whose sole stockholder was the United States. Supporters not only praised the project for supplying hydroelectric power and generating jobs, but they also hailed it as a public good because it would make clear the fair, legitimate cost of electricity.

Texans on all ends of the political spectrum agree that the price of energy over the course of last month’s crisis was anything but fair. Many residents, especially those with variable-rate power plans that charge different prices for electricity depending on demand, received exorbitant bills when prices on the ERCOT market skyrocketed. Governor Greg Abbott held an emergency meeting on the issue, and the state’s Attorney General launched an investigation into communications between ERCOT and the providers, but it is still not clear what state regulatory changes might flow in the months to come.

Will this recent disaster in Texas bring about significant changes in the state’s energy sector? It is possible that companies will take steps toward hardening the infrastructure with investment in things like jackets on instrument panels or perhaps tweaking the competitive wholesale power market in ways that incentivises investment in backup power. Larger scale changes in consumer protection, however, do not fit the present context and would likely take some years of extensive political work.

Throughout the 1990s Texas energy executives like Enron’s Ken Lay pushed for deregulated energy, writing to then-Governor George W. Bush about how electricity deregulation would mean more competition and lower electric rates. While it did not necessarily bring the lower electricity bills as promised, Enron’s push for deregulation did succeed in Texas. In 1999 Governor Bush signed legislation that removed controls on wholesale electricity prices and eliminated tightly regulated local monopolies.

Even with pending lawsuits, investigations, and a moratorium on electricity disconnections for non-payment, it is hard to detect much appetite for regulation among Texas politicians. When Governor Abbott announced the end of the state mask mandate this week, he said, “people and businesses don’t need the state telling them how to operate.” This action, in a state with only 6.5 per cent of adults fully vaccinated, contradicts the advice of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, but his announcement struck a best-government-governs-least chord. One wonders if and when that rhetoric loses potency.

And yet, historical analysis of certain government regulations highlights the potential of turning to electoral politics in the wake of disaster.