US President Donald Trump’s path to re-election requires maximising the support of his oft-mentioned “base” — white voters without college degrees — in the key battleground states where he eked out a victory in 2016.

This is because Trump’s support among other voters has slipped. According to the Pew Research Centre, he still holds a 60-34% lead over Democratic challenger Joe Biden among whites without a college degree, but Biden has substantial leads among college-educated white voters, as well as Black, Hispanic and Asian voters.

As a result, Trump has a very narrow path to victory that will require high voter turnout by so-called “working-class whites” in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Florida, Wisconsin and Michigan. Based on the current polls, this path is increasingly unlikely.

Trump has a very narrow path to victory that will require high voter turnout by so-called “working-class whites” in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Florida, Wisconsin and Michigan. Based on the current polls, this path is increasingly unlikely.But that doesn’t mean it’s impossible.

But that doesn’t mean it’s impossible. According to Dave Wasserman, an elections analyst from the Cook Political Report, Trump’s base is key.

In Pennsylvania, for instance, he estimates there are about 2.4 million non-college-educated white voters who did not cast ballots in 2016 but could do so this year. As Wasserman notes,

the potential for Trump to crank up the intensity of turnout among non-college whites is quite high.

Who are ‘white working-class’ voters?

Whites without a college degree in America are often referred to as the “white working-class”. In truth, this label is used rather loosely.

The “working class” has long been thought of as “blue-collar” factory, trades and construction workers.

But according to US political scientists, the working class today is defined by both education and income levels:

those who do not hold a college degree and report annual household incomes below the median, as reported by the Census Bureau (in 2016, for instance, the median annual household income was nearly US$60,000).

Under this definition, small business owners and various “white collar” workers (those in service jobs) and “pink collar” (jobs traditionally held by women such as caregiving roles) are also considered part of the American working class.

Working-class voters have long held the key

Working-class voters have long played an outsized role in US elections, despite the fact they have been a minority among wage and salary earners since the 1920s.

Working-class voters, particularly those who belonged to unions, were once steadfast supporters of candidates on the political left. These days, however, the left feels largely abandoned by these voters, while the right is increasingly dependent on them to win elections.

Policies that address economic inequality are the best way to guard against the white working class being drawn to populist figures like Trump. Biden has not offered these voters much more than Clinton did, with the possible exception of more empathy.

As working-class voters have drifted to the right, the labels used to describe them have changed. In the 1970s, they were called “hard hats”. By the 1980s, they were known as “Reagan Democrats”, and in the early 2000s, “NASCAR Dads”.

In the UK, they have been known as “working-class Tories”, and in Australia, “Howard’s battlers”.

The story of working-class whites abandoning left-wing parties makes for catchy journalistic copy. Each election cycle, there are numerous articles and television vox pops featuring machinists or miners who have moved rightwards, feeling disillusioned with the parties of their parents.

Books like The Inheritance, Hillbilly Elegy, Strangers in Their Own Land and What’s the Matter with Kansas? have also tried to capture the essence of this changing working class and why these voters have drifted to the right — and at times, voted against their own economic interest.

Working-class voters are more complex than we think

The only problem with this narrative is that it is all too neat. In reality, the voting behaviours of the white working class is more complex.

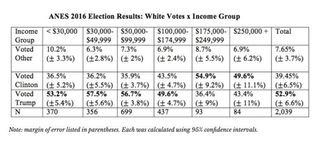

Take for instance Trump’s supporters in the 2016 election against Hillary Clinton. As the data below show, Trump didn’t earn his largest share of votes among the poorest whites in America, but among those in the “middle class” (that catch-all label used to describe everyone between the rich and those living under the poverty line).

More than 10% of white voters with incomes under $30,000 actually voted for a candidate other than Trump or Clinton.

So, while Trump won large numbers of white working-class votes compared to Clinton, experts say it isn’t clear he motivated more of these voters to the polls.

Other factors may also have come into play in 2016 that weren’t related to either income or education.

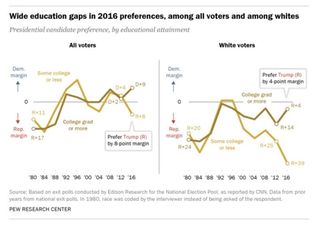

As this chart shows, non-college-educated voters split their voting preferences evenly between Democrats and Republicans as recently as 1996.

An accelerated shift to the right began then, resulting in a remarkable 39% margin of support for Trump over Clinton in 2016. For many scholars, this “diploma divide” was the single most important explanation of why Trump won.

But many commentators have also pointed to racism and xenophobia to help explain Trump’s rise among these white working-class voters.

According to Identity Crisis, a widely praised book on the 2016 election, Trump successfully “racialised economics” by promoting to white Americans

the belief that undeserving groups are getting ahead while your group is left behind.

Biden shows empathy with working-class voters, but few new ideas

Have the Democrats tried to woo back these white working-class voters in recent elections?

In recent elections, former President Barack Obama, Clinton and Biden have focused much of their economic rhetoric on industrial and construction employment, even though these sectors only make up 20% of all jobs (the rest are in the services sector).

Most politicians lack the language to explain the reality that most jobs are service jobs. Because of this, it is hardly surprising they also lack good ideas to address unequal wages and poor working conditions within the services sector.

Policies that address economic inequality are the best way to guard against the white working class being drawn to populist figures like Trump. Biden has not offered these voters much more than Clinton did, with the possible exception of more empathy.

But Biden may not need to win over working-class white voters to defeat Trump. With minority voter turnout expected to be high, and fewer white women and elderly voters expected to support Trump, the president’s hopes of winning on a shrinking base are looking ever more remote.