Executive summary

Australia has entered a new era of intense strategic competition and must find new ways to both develop and finance its national security. Specifically, the Australian Government must draw in the private sector – consisting of capital lenders, equity providers – and national security and technology companies to create sovereign defence capabilities. The urgency of the challenge and need for government to do business differently from the past is captured in the 2023 Defence Strategic Review (DSR).

The DSR emphasised the need for a more “whole-of-nation approach” to Australia’s national defence that harnesses “all elements of national power.” The Review brought into stark relief the sheer scale of Australia’s national security needs over the coming decades. Beyond fielding new military capabilities, Australia requires infrastructure and facilities, manufacturing capability, logistics and everyday operational requirements, and workforce support. The Australian Government agreed with the DSR’s recommendations in whole or principle and made one of its priorities for immediate action to rapidly translate emerging technologies into capability in close partnership with Australian industry.

Although the end goal has been articulated, the path to leveraging the private sector for national security is not straightforward. As a starting point, it requires appreciating Australia’s current domestic capacity and private sector appetite for partnership as well as how all the different moving parts fit together to create a functioning whole. Ultimately, Australia must create a ‘defence-finance-tech ecosystem’ where one has not existed previously.

Creating a defence-finance-tech ecosystem is not just a matter of convincing Australian capital providers like banks, superannuation funds, private equity and venture capital of the business case and identifying appropriate domestic defence and technology companies to enlist. As this report unearths, producing sovereign defence capability for Australia in a self-sustaining system at speed requires targeted policies geared to multiple dimensions. It involves policies directed towards Australian defence and dual-use start-ups and small and medium enterprise (SME); foreign-owned Defence Primes; Australian industry groups and networks; the university and academic sector; the AUKUS partnership; private capital across the spectrum; different government agencies; and Commonwealth Ministers. Multiple stakeholders with different interests and priorities must be forged together for the national good.

As this report unearths, producing sovereign defence capability for Australia in a self-sustaining system at speed requires targeted policies geared to multiple dimensions.

This report’s broad driving question of how to finance national security has generated numerous recommendations for action. Individual recommendations have varying levels of urgency, with some that could be acted on immediately while others require sustained effort over years. One recommendation that, if implemented, would underpin progress is to map Australia’s defence and dual-use companies and investment landscape. Such a resource would be valuable to government, business, and private capital alike.

The report’s other recommendations are directed towards addressing challenges associated with three broad groups: (1) Australian start-ups, small and medium enterprise, and universities; (2) Australian industry, private equity and venture capital; and (3) the Australian Government. Although there are too many recommendations to summarise here, critical, enabling recommendations with the greatest capacity to move the dial are below.

Short term

- Defence should accelerate outreach to a wide group of private sector actors on the Advanced Strategic Capabilities Accelerator (ASCA) and AUKUS Pillar II advanced capabilities priorities and establish an AUKUS Pillar II “trusted network” to advise ASCA on relevant technology issues.

- The Treasurer’s Investor Roundtable should be convened to deepen collaboration between government and the investment community on Australia’s national defence priorities.

- An independent Private Capital Advisory Board should be established to provide high-level guidance to the Department of Defence on capital sources, financing instruments and talent.

Medium term

- Government should create a stronger demand signal to business by developing a clear investment pipeline for core Defence functions and enabling industries and offering co-investment.

- To support strategic defence investment, government should play a matchmaker function to connect start-ups and SMEs with private investors where the path to procurement is clear.

- When speed to capability is required, rather than a blanket pre-requisite for open tenders, Defence should select known and trusted Australian suppliers, companies, and Defence Primes with a track record of delivery.

More challenging reforms include

- Continuation of Defence restructuring its procurement contract process to reduce the costs for SMEs of doing business with government.

- Cultural change in the Defence Department to accept greater risk through Senior Executives leading by example, ministerial-level political support, and APS reward structure.

Each of these recommendations comes with its own challenges be they systemic, structural, legislative, procedural, cultural, or convening. In many cases, they not only require a commitment to new ways of operating but also a change in mindset and approach of government ministers and their supporting departments. This will be more difficult than the everyday challenges faced by government and, in some cases, these recommendations upend decades of entrenched policy and practice. Implementing these changes will feel uncomfortable for department officials and place greater pressure on government ministers to deliver results. But, without this change, government processes and defence industry will not move fast enough to rise to the challenge presented by the current strategic circumstances and will fall short of implementing the DSR’s recommendations and AUKUS requirements.

Without this change, government processes and defence industry will not move fast enough to rise to the challenge presented by the current strategic circumstances and will fall short of implementing the DSR’s recommendations and AUKUS requirements.

While its strategic challenges are daunting, Australia has the benefit of working closely with allies and partners in the Indo-Pacific region in meeting them. Responding to the DSR, Australia’s Defence Minister Richard Marles underscored the need for Australia to continue to work closely with its Alliance partner, the United States, to achieve strategic balance and stability in the region. The US defence enterprise offers critical lessons and manifold opportunities for a partner such as Australia looking to harness private sector technological prowess and capital for national security purposes.

Two factors above all have sharpened the US Government’s focus on better connecting national security to commercial technologies and private finance: the challenge posed by China to US military and technological primacy, and a profound transformation in the US national innovation system towards one where the private sector now dominates R&D for new technologies. This report draws five key lessons from the US finance-defence-tech ecosystem:

- The paramount importance of military strategy in overcoming status quo bias – faced with the challenge of military modernisation at speed, strategy must be in the driver’s seat. Reforms to acquisition processes may yield dividends, but clarity as to what to buy (rather than how to buy) is even more critical.

- Leverage your strengths – harnessing existing and emerging private sector strengths is a better approach than seeking to recreate a more government-centric innovation system.

- Coordinate, coordinate, coordinate – with defence R&D only a fraction of the Pentagon’s, there is no alternative for Australia’s Defence Department but to focus on better coordination and collaboration across government and the private sector to deliver advanced capabilities.

- Money matters, but so does culture – governments need to work simultaneously to improve financial incentives and change cultural parameters to deepen private sector involvement in the defence enterprise.

- Innovation does not rely on an org chart – the US defence-finance-tech ecosystem underscores the power of networks in the innovation process with no single pipeline or pathway to success.

Concrete steps should be taken by the US and Australian Governments in the context of the Alliance. These include:

- Establishing an Australian presence for the Pentagon’s Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) in order to draw from US experience leveraging commercial technologies for military application, and to widen the pool of potential capital sources for Australian technology companies.

- Embedding an Australian Defence presence in the Pentagon’s Office of Strategic Capital to assess the most effective tools for enlisting patient, private capital investment in new and emerging technologies.

- Progressing a series of shared technology initiatives, including AUKUS Pillars I and II and the successful conclusion by the US Government of International Trade in Arms Regulations (ITAR) reforms.

Australia’s national defence task calls for new models of collaboration between government and sections of society – private capital providers, dual-use technology companies, university research institutes and the like – that traditionally have not seen national security as core business. Although all parties will need to come together for a successful outcome, the driving force needs to originate with government. The private sector has commercial imperatives. Yet for Australia’s Defence Force to have the capabilities it will require in the future, government must attract a wider network of private sector actors. The report provides targeted solutions in support of that goal.

Australia's national security financing challenge

Australia’s senior most leaders and recent strategic documents recognise that Australia faces its most challenging security environment since the Australia’s senior most leaders and recent strategic documents recognise that Australia faces its most challenging security environment since the Second World War (WWII).1 China’s rapid military expansion and challenge to US hegemony, Russia’s illegal war in Ukraine, grey zone warfare and economic coercion, and rapid technology advancements are combining to create a less stable and more competitive international environment. As well as a deteriorating strategic outlook, domestically Australia faces major fiscal challenges. Large national expenses for health, aged care, disability insurance, and servicing government debt are adding additional pressure to the Commonwealth. Against this backdrop, the Australian Government must find ways to pay for and speed up the delivery of national security for the public good. This is the urgent challenge this report seeks to address.

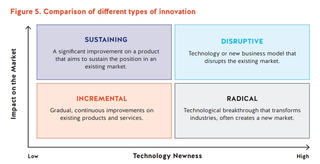

For its part, the Australian Government has committed to spend more on defence and broader national security. In the 2023-24 Budget, the government committed to increase defence spending from its current 2.1 per cent to around 2.3 per cent of GDP by 2030.2 More broadly, the government is also financing the National Reconstruction Fund (NRF) to the tune of A$15 billion, including A$1 billion each for advanced manufacturing and critical technologies. Although these additional resources are channelled to national defence and related industries, there is a resource shortfall. This is evident in the defence capability trade-offs already being made, including ‘reprioritising’ and cancelling existing defence projects.3 Increased commitment of public funds by the government should be seen as a necessary but not sufficient condition for the sort of defence investment and preparedness demanded by the Indo-Pacific’s deteriorating strategic outlook. The independent 2023 Defence Strategic Review (DSR) public version provides a useful lens to approach the challenge of financing Australia’s national security. Three themes of the DSR serve as anchor points for this report. The first is the call for a “much more whole-of-government and whole-of-nation approach” to defence and national security based on harnessing all elements of national power. The second is the imperative for a more rapid translation of emerging and disruptive technologies into advanced military capabilities. And the third is the need for new approaches to defence capability acquisition, procurement, risk management and innovation that reflect the scale and urgency of Australia’s strategic challenge.4

Taken together – a whole-of-nation effort, rapid translation of technology to capability, and faster pathway to defence outcomes – it becomes clear that the necessary response is for Australia to urgently develop a new defence-tech-finance ecosystem.

Taken together – a whole-of-nation effort, rapid translation of technology to capability, and faster pathway to defence outcomes – it becomes clear that the necessary response is for Australia to urgently develop a new defence-tech-finance ecosystem.

The DSR identified the need to enlist a wider network of public and private sector actors and institutions that would support Australia’s national defence strategy beyond the narrow, traditional focus on the Department of Defence and defence industry firms. To implement the DSR’s recommendations, Defence will need to forge new collaborations with sections of society such as private capital providers, dual-use technology companies, and university research institutes that traditionally have not seen national security as their core business. This sort of holistic thinking and whole-of-nation approach to national defence has been rare outside of wartime, certainly in Australia. However, today’s strategic environment demands a more joined up approach.

Getting more private sector skin in the game

A wider network of private sector actors will need to be enlisted to deliver the Australian Government’s ambitious national defence strategy, including the full range of advanced capabilities the Australian Defence Force (ADF) will require in the future. The Department of Defence needs to “take risks and do business differently” (a point acknowledged explicitly by senior Australian officials in consultations for this report). Although, the challenge presented by Australia’s changed strategic environment is not one for Defence to grapple with alone.5 This dual reality comes through clearly from the DSR.

The DSR, as well as outlining the scale of Australia’s security challenge, provides an indicative guide to the substantial commercial opportunities for Australia’s private sector in the defence and national security realm over the coming decades. These extend well beyond a focus on advanced technology capabilities and include major investments in infrastructure and facilities, new sovereign manufacturing capability, logistics and everyday operational requirements, and workforce support.

A non-exhaustive list of DSR priorities endorsed by the Australian Government includes:

- Infrastructure developments and upgrades for the Nuclear-Powered Submarine Pathway

- Sovereign industrial capability for the acquisition of nuclear-powered submarines

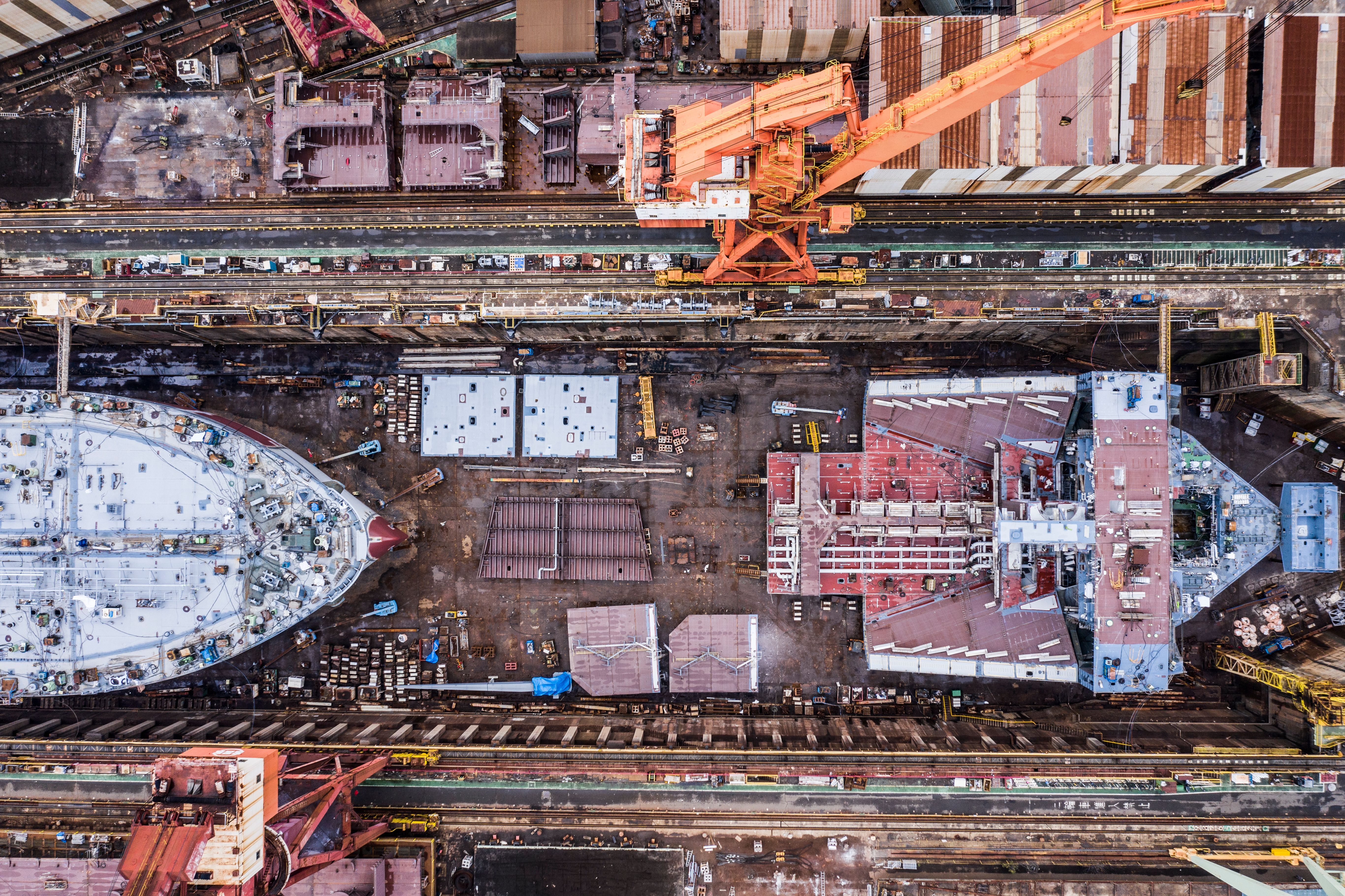

- A commitment to continuous shipbuilding › Development of domestic missile capability

- Enhanced domestic manufacturing of Guided Weapons and Explosive Ordnance

- The upgrade and development of Australia’s northern network of bases, ports and barracks

- Fuel storage and supply

- Transport logistics tasks

- Accelerated development of AUKUS Pillar II capabilities

- Additional enhanced cyber and space domain capabilities › Workforce training challenges, including ICT and cyber, capability acquisition, engineering, project delivery, and finance.6

This extensive demand pipeline, federal budget constraints, and the need to tap private sector resources and technological capability suggest a broad lens be adopted when considering the scope for public-private partnerships and new mechanisms to facilitate private investment. The task will require considerable flexibility in Department of Defence operating procedures, authorities and policy instruments, as well as additional investment in specialist expertise. There is no cookie-cutter approach for working with a diverse range of defence, finance and technology firms as well as research institutions, or for developing policy tools to pull through private capital investment. This flexibility and agility go to the nub of what it means for Defence to take risks and do business differently in a new era. Key lines of effort for deeper public-private collaboration should include: (1) dual-use technology companies and start-ups with products and services at mid- to late-stage development; (2) potential investors in defence infrastructure and infrastructure-like projects looking for stable, long-term rates of return; and (3) Australia’s defence sector small and medium enterprises (SMEs)7 where improvements in government communication, support, innovation and contracting processes can help unlock greater private financing for sovereign capability at scale.

These lines of effort in no sense diminish the role of large, global Defence Primes8 in Australia’s defence enterprise. They will remain central to capability development and defence industry policies geared towards the acquisition of major platforms or weapons systems, such as naval ships or guided missiles. The Primes are, however, well known to government defence planners. And in the context of nurturing a nascent defence-finance-tech ecosystem, they tend not to be direct sources of disruptive technologies (compared with technology firms with private customer-facing, dual-use products and services). Nor are they likely to rely at the margin on Australian financial institutions for capital.

Recommendations

- Defence should adopt a broad lens when considering the scope for greater private capital investment

- Key lines of effort should include: (1) dual-use technology companies and start-ups with products and services at mid- to late-stage development; (2) potential investors in defence infrastructure and infrastructure-like projects; and (3) Australia’s defence sector SMEs where improvements in government communication, support, innovation and contracting processes can help unlock greater private financing for sovereign capability at scale.

Harnessing private finance: A first step

The Albanese government’s endorsement of the DSR’s central recommendations and the pipeline of future investments sketched above opens the door to a national conversation about the role that private finance can play in supporting Australia’s national security objectives. This issue takes on added significance given the deterioration in the regional strategic environment and the reality that many critical technologies with both commercial and military applications rely on private sector innovation systems and private capital investment. Importantly, the foundations for this new conversation are in place.

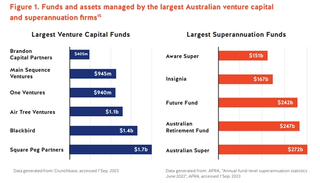

At a broad level, Australia has sophisticated and mature private capital markets and a well-regulated financial sector. It has the world’s fifth largest pool of pension assets based on the nation’s superannuation system, and the world’s 11th largest stock market. The Australian dollar is the sixth most traded currency internationally.9

Australian banks are strongly capitalised, profitable, and held to high standards by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA). These banks – especially the four major retail banks – are a key source of finance to Australian SMEs, which form the vast majority of firms in the Australian defence industry. More than 90 per cent of outstanding debt owed by Australian SMEs is held by banks, and SMEs in Australia are three times more likely to apply for debt than equity financing, in part because SME owners usually want to maintain control of their business and avoid diluting their equity.10

Other forms of non-traditional finance (with new products and providers including non-bank lenders) have grown strongly over the past decade, though off a low base. While these forms of funding can be more expensive than bank financing, processes around obtaining finance can be quicker and easier, helping to build momentum at key stages of business growth.11

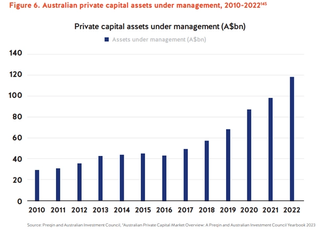

Private equity and venture capital (VC) firms increasingly provide sources of financing to innovative technology enterprises in Australia. Australia-focused private capital assets under management more than doubled in the past five years, reaching an estimated A$118 billion as of September 2022. Of this total, private equity accounted for A$41.7 billion (35 per cent) and the VC industry for A$17.9 billion (15 per cent).12 With their central role in Australia’s innovation and tech start-up ecosystem, private equity and venture capital need to be part of the conversation on harnessing private finance for national security.

Superannuation funds also need to be at the table. The continued growth and consolidation of superannuation funds in Australia continues to transform the Australian investment landscape. Around 17 million Australians collectively own around A$3.5 trillion in superannuation assets.13 The superannuation system presents an important source of capital in the Australian economy and superannuation funds have shown increasing interest in alternative investments in recent years, including private equity and venture capital. So too has the Future Fund (Australia’s sovereign wealth fund).14 There are considerable opportunities for superannuation funds in areas such as defence infrastructure investment.

Treasurer Jim Chalmers has made a point of engaging Australia’s private finance community on future investment needs in areas of national priority. Established in October 2022, the Treasurer’s Investor Roundtable brings together leaders in the investment community including some of Australia’s largest superannuation funds, the major banks and global asset managers focusing on particular asset classes. Initial areas of focus have been on housing and clean energy.16 In August 2023, the Treasurer observed that there is “an opportunity for the defence industry to be a bigger part of our thinking when it comes to the role of superannuation and other institutional investors in our economy.”17

There is no more important national priority than securing the investment foundations of national security.

There is no more important national priority than securing the investment foundations of national security. At the earliest opportunity, the Treasurer’s Investor Roundtable should be convened to deepen government collaboration with the private finance community on Australia’s national defence priorities. To inform this discussion, Defence – working with Treasury and the Department of Finance – should undertake a detailed analysis of the Defence balance sheet, including stock and flow variables. This would help to identify the potential role private capital could play through direct funding mechanisms, helping in turn to free up scarce taxpayer resources for vital national security priorities. Any discussion of private financing for national security capabilities inevitably raises issues around environmental, social and governance (ESG) investing, a topic that has become increasingly prominent in recent years. These issues should be aired openly and viewed holistically, given the wide range of investment opportunities in the national security realm and the evolving strategic threats confronting Western liberaldemocracies. At least in northern hemisphere financial capitals, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 has spurred a more nuanced and realistic discussion about ESG constraints on investment in defence firms and defence-related activities given the new security challenges facing free and open societies.18

The Treasurer’s Investor Roundtable provides a useful forum for discussing ESG issues, including the ‘boundary cases’ where private financing of national security capabilities will remain limited. An important area of focus should be on private capital sources in Australia for dualuse technology companies, without losing sight of the broad scope for private investment in defence firms and relatively uncontroversial areas such as infrastructure. Together with the Treasurer, the Defence Minister should lead this conversation.

Recommendations

- The Treasurer’s Investor Roundtable should be convened at the earliest opportunity to deepen collaboration between government and the investment community on financing Australia’s national defence priorities

- To inform this discussion, Defence – working with Treasury and the Department of Finance – should undertake a detailed analysis of the Defence balance sheet, including stock and flow variables

- Together with the Treasurer, the Defence Minister should lead a conversation on the impact of environmental, social and governance constraints on private financing of national security capabilities

Rethinking defence innovation: Understanding the power of networks

Another significant pillar of a dynamic and robust defence-finance-tech ecosystem is Australia’s scientific research community. The DSR highlighted the importance of fast-tracking the translation of scientific and technology research into advanced military applications. In the process, it shone a spotlight on Australia’s defence innovation system and the need for reform.

The Australian Academy of Science reports that, in global terms, Australia has contributed to more than 4 per cent of the world’s published research, while having just 0.3 per cent of the world’s population.19 Several Australian universities score highly on international rankings of research output, including in areas relevant to military modernisation such as engineering and quantum computing.20 In general, however, Australia sits well below OECD average levels on R&D spending (government and private sector combined).21 As a share of total federal government R&D spending, defence R&D fell from around 11 per cent at the end of the 1980s to around six per cent in the early 2000s. This share has remained broadly stable since then, with Defence portfolio R&D expenditure put at A$646 million in 2022-23.22 This compares with strong growth in an area such as health and medical research which, at time of writing, accounts for more than 20 per cent of total government R&D spending in Australia.23

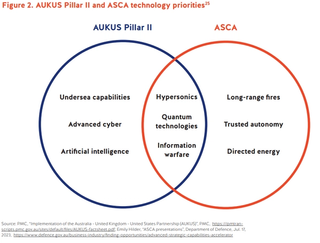

The DSR placed particular emphasis on the need for clear demand signalling by Defence to industry and the research community, including the university sector, and highlighted the critical role of international partnerships in accelerating the development of more technologically advanced capabilities. Specifically, the DSR recommended the development of AUKUS Pillar II Advanced Capabilities be “prioritised in the shortest possible time.”24 As part of AUKUS Pillar II, Australia, the United States and the United Kingdom agreed to collaborate across a spectrum of critical technology areas.

List of AUKUS Pillar II Advanced Capabilities

- Undersea capabilities

- Quantum technologies

- Artificial intelligence (AI) and autonomy

- Advanced cyber

- Hypersonic and counter-hypersonic capabilities

- Electronic warfare (EW)

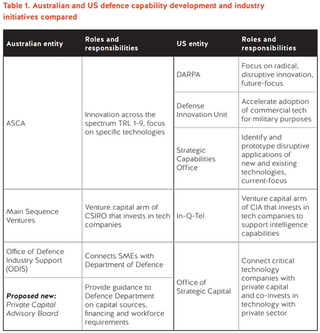

A key focal point for advanced technology capability development in Australia is the Advanced Strategic Capabilities Accelerator (ASCA) within Defence. The priorities identified for ASCA are hypersonics, directed energy, trusted autonomy, quantum technology, information warfare and long-range fires. As such, ASCA is charged with delivering innovation outcomes for some, but not all, AUKUS Pillar II priorities.

While reforms to government structures and processes have the potential to pay real dividends in this area, no less important is embedding a firmer grasp within government, including the Defence Department, of the intangible (and messy) features of the innovation process. Part of accepting greater risk is embracing in practice a networked approach to the innovation process, including a greater willingness to share information with trusted technology partners within industry and the research community.

In his 2020 book How Innovation Works, science writer Matt Ridley offers an array of examples (through history and across various fields) of how innovation is invariably a “bottom-up” (not “top-down”) process.26 He argues innovation arises most commonly from networks, not hierarchies, created through the exchange and recombination of ideas, often in a manner that is unpredictable and serendipitous. Wherehierarchies tend to reinforce stability, clear lines of authority and standardised delivery against established processes, networks are characterised by their decentralised nature. Their strength lies in their ability to foster creativity, leverage diverse perspectives and encourage collaboration that can ultimately form an ’ecosystem.’27

Another name for an ecosystem is a ’trusted partner network’. Building such networks across diverse and otherwise siloed domains of Defence, other arms of government, the finance sector, the defence industry, technology firms and the broader research community will not arise from business as usual. And while additional resources will be necessary, spending alone will not of itself deliver much-needed innovation outcomes. Defence will need to mobilise a network of critical technology stakeholders, working with other centres of knowledge within government, including the Department of Industry, Science and Resources, the Department of Home Affairs, the Department of Education, and CSIRO’s Main Sequence Ventures. As part of this exercise, and consistent with a whole-of-government approach to national defence, the Australian Government’s Chief Scientist should be afforded full visibility and scope for input into defence innovation reform.

A prime candidate for urgent attention is the development of an Australian AUKUS Pillar II ‘trusted partner network’. In key AUKUS Pillar II critical technology areas, such as AI and quantum computing, the vast bulk of expertise and investment capacity sits outside government. By its nature, this network will take in researchers, financiers, and entrepreneurs as well as government decision makers, many of whom are yet to conceive of themselves as part of such an ecosystem. This would build on emergent networks in select technology areas in AUKUS partner countries. For example, the UK Government has established the UK National Quantum Technologies Programme as a collaboration between industry, academia and government to secure emerging quantum opportunities, while Australia’s National Quantum Strategy aims similarly to build a thriving Australian quantum ecosystem by improving coordination and collaboration between government, research bodies and industry.28

Government has a critical role to play in deploying its unmatched convening power to bring stakeholders together, provide essential information, communicate a clear policy direction, and present itself as open to working flexibly towards shared technology goals as part of delivering on AUKUS Pillar II. This will need to occur based on a support structure of fast-tracked security clearances and enhanced cyber protection. The resourcing of these issues should be a priority, along with accessing specialist skills in the key technological areas of ASCA and AUKUS Pillar II.

Recommendations

- The Australian Government’s Chief Scientist should be afforded full visibility and scope for input into defence innovation reform

- Defence should establish an AUKUS Pillar II ‘trusted partner network’ to advise ASCA on relevant technology issues, with additional resources devoted to fast-tracking security clearances and cyber protection as a matter of urgency.

Shape – Attract – Scale: An organising narrative for Defence

Economist Robert Shiller has identified the important role narratives can play in shaping public policy, as well as organisational and economic behaviour.29 Narratives serve to orient government decision making and influence the response of societal actors. Three watchwords – Shape, Attract, Scale – encapsulate the task for Defence in seeking to harness private sector investment and capability in support of Australia’s national security objectives.

An explicit narrative is a way of reinforcing the clear directive and mandate provided by ministers to streamline processes, make quicker decisions, accept more risk, and devise innovative mechanisms to tilt financial metrics on specific investments. By fostering a shared sense of mission across Defence stakeholders, it gives day-to-day meaning to the injunction for a new organisational mindset and greater licence for defence officials to take different approaches or means to achieving set objectives or ends. In the process, Defence leaders can incentivise personnel to pursue problems and technologies that are deemed to be of the highest priority and to share information, coordinate and collaborate more readily.

An organising narrative would also aid public understanding and awareness that national defence should no longer be thought of as a public good that can be delivered solely through government resources and processes. It would therefore help to play an educative role within the wider Australian community, one that accords with the thrust of the DSR based on the need for a more unified, whole-of-nation approach to Australia’s strategic environment. This is especially important given prevailing trends and debates within the finance sector regarding legitimate areas for ethical investment in the public interest.

The imperative to shape reflects the centrality of clear and continuous communication with stakeholders about what precise capabilities Defence is seeking to acquire. It draws maximum leverage from the unmatched convening power of government, but equally implies government will place deeper trust in partners called on to put their own financial ’skin in the game’.

The need to attract investment ultimately highlights the need for commercial benchmarks to be met, where private sector parties make investments on a risk-weighted return basis. This underscores the need for stable, longterm government funding commitments and for flexibility in policy tools and instruments and in contracting terms geared to pull through private capital. Consultations with private capital providers for this study underlined their responsiveness to the detail of contract terms.

A focus on scale reinforces the essential element that underpins sustainable businesses and a durable, robust ecosystem capable of developing innovative solutions to capability challenges. Scale is the factor that makes a defencefinance-tech ecosystem more than the sum of its parts, and ultimately one that is dynamic and self-sustaining.

Of course, the issue of scale looms large in another sense. Australia accounted for an estimated 1.4 per cent of total military expenditure of the 15 countries with the highest spending in 2022 – lower than Italy (1.5 per cent), though higher than Canada (1.2 per cent).30 The United States, as Australia’s strategic alliance partner, accounted for an estimated 39 per cent of total expenditure.31 The relatively modest scale of Australia’s defence enterprise in global terms necessarily imposes constraints and trade-offs.

Modest scale should not mean sub-optimal effort or outcomes. On the contrary, “manageable” scale can provide Australia with an advantage in working with larger allies and partners. AUKUS Pillar II provides the ideal vehicle for greater clarity of focus and superior networked coordination of effort. A strong and cohesive national offering should define Australia’s approach to technological capability development under AUKUS Pillar II. This would better position Australia to leverage international technology partnerships for national security dividends.

Recommendation

- Defence should establish an explicit organisational narrative to foster a shared sense of mission and help orient policy and personnel towards the goal of harnessing private finance for national security.

The US defence-finance-tech ecosystem: Lessons from a work in progress

Enlisting more private sector resources and capability for national security purposes, translating new and emerging technologies into advanced military capability, and reforming defence innovation and capability acquisition systems that are no longer fit for purpose have been (and continue to be) the subject of analysis and multiple policy initiatives in the United States. The parallels between the military imperatives and challenges of Australia and its alliance partner are demonstrable.

The Pentagon once played a central role in the US national innovation system as investor and first adopter, based on its far-reaching contracting power and ability to direct research. By contrast, the private sector now dominates R&D for new technologies, with a focus on the development of new products and services for commercial markets. This transformation in how America creates new technology – and what it creates – has altered immeasurably the relationship between US national security and innovation activity.

The global military primacy of the United States has long rested on unrivalled strengths in foundational research, innovation, and technology development. This position is now under clear and present threat with the rise of China across military, economic, and technological domains. Various studies have pointed to the United States falling behind China in key critical technologies and highlighted weaknesses in the US defence industrial base.32 Further gaps and vulnerabilities were exposed in the wake of Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, with mounting evidence that the Pentagon faces not only production line challenges but also difficulties gaining access to elements essential to the manufacture of modern military technologies.33 This backdrop helps explain a sharpened focus within the US Government on better connecting national security to private sector finance and technology development.

The Biden administration’s 2022 National Security Strategy (NSS) surveyed a world where the risk of conflict between major powers is increasing, competition to develop and deploy foundational technologies is intensifying, and authoritarian powers are working more aggressively to implant and export illiberal models of domestic and global governance.34 The 2022 US National Defense Strategy (NDS) outlined how fast-evolving technologies and applications “are complicating escalation dynamics and creating new challenges for strategic stability” – where new applications of artificial intelligence, quantum science, autonomy, biotechnology, and space technologies have the potential not just to change kinetic conflict, but also to disrupt day-to-day supply chain and logistics operations.35

The 2022 NDS calls for urgent action to “build enduring advantage across the defense ecosystem – the Department of Defense, the defense industrial base, and the array of private sector and academic enterprises that create and sharpen the Joint Force’s technological edge.”36 A major emphasis is given to close collaboration with allies and partners, with the Pentagon charged with incorporating them at every stage of defence planning.

Being the world’s largest military power and the nation with the deepest and most sophisticated “finance-tech” complex globally, the US defence enterprise offers critical lessons and manifold opportunities for a partner such as Australia looking to harness private sector technological prowess and capital for national security purposes. Not all these lessons are positive or readily applicable. Yet the sheer scale and breadth of the US military footprint in adjusting to new strategic and technological realities provides valuable insights on the approaches and tools that may be useful to attract private investment and convert new technological advances into military capabilities.

From Los Alamos to Big Tech

The marriage of national security objectives to technological innovation and private sector capital (often seeded by federally-funded R&D expenditure) is by no means a new story for the United States. Various forms of what now would be called public-private partnerships have been central to the development of US defence capabilities from the earliest years of the Republic.

In the 20th century, WWII inspired unprecedented whole-of-nation mobilisation with the United States acting as the manufacturing arsenal of democracy and global technological frontier. The harnessing of government, industry and cuttingedge scientific research during wartime found unique institutional expression in the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) led by Vannevar Bush. OSRD provided funding and advice for cutting-edge missions (from the Manhattan Project to radar technology to antibiotics development). At its peak, it directly employed almost 6000 US scientists across 300 universities.37

Through the Cold War, the United States was able to combine prominent emerging technologies with new operational concepts to overcome the numerical superiority of Soviet forces, first with nuclear weapons and later with precision weapons and stealth. In the 1950s and beyond, the US military played an important role in the rise of Silicon Valley and the development of the United States’ electronics industry. In 1958, the US Government started a program allowing for the creation of small-business investment companies (SBICs) that would receive cheap government loans and tax breaks to invest in other small companies. In the process, military investments helped seed the emergent VC industry and by the mid-1960s, there were hundreds of small investment companies.38

Also founded in 1958 in the wake of the ‘Sputnik shock’, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) is the US Department of Defense’s research and development agency.39 DARPA’s role in making pivotal investments in breakthrough national security technologies with wider application is well acknowledged. With an annual budget of around US$3.5 billion, DARPA lays claim to at least partial credit for game-changing developments including Global Positioning Systems (GPS), stealth technologies, drones and the internet.40 It formed one part a wider government-led innovation ecosystem that encompassed federally-funded R&D centres, university-affiliated research centres, national laboratories, as well as a range of other government departments and agencies.

In the 1980s, the US Government launched further projects designed to develop and harness new technologies for national security purposes. The Strategic Defense Initiative, for example, stimulated considerable research on missile defense technologies and, following congressional authorisation, for the first time the Pentagon began investing directly in technology start-ups. Between 1982 and 1988, the federal government, led by the Department of Defense, spent more than US$1.35 billion on such startups – nearly 10 per cent of all venture capital investment over this period.41 Late in the decade, DARPA helped fund SEMATECH, a consortium of chip manufacturers founded to help advance US research on semiconductors.

The end of the Cold War and resulting declines in defence spending saw national security slip progressively from the centre of the US national innovation system.

The end of the Cold War and resulting declines in defence spending saw national security slip progressively from the centre of the US national innovation system. In the 1990s, US geopolitical dominance, the rise of the information economy, and deeper globalisation within a liberal marketbased order contributed to the emergence of a more decentralised, diverse and commercially-oriented national innovation system. The nexus between large, agile and sophisticated sources of private capital and Silicon Valley came to play an outsized role both in the US national innovation system and in the structural transformation of the US economy.

These developments were not lost on parts of the US national security community. Among early initiatives designed to leverage emergent information and communications technologies for national security purposes was the establishment in 1999 of In-Q-Tel (IQT), a non-profit arm of the US intelligence community. IQT continues to perform a focused role as a strategic investor and vehicle for harnessing cutting-edge (usually dual-use) technologies coming out of Silicon Valley.42

In-Q-Tel as an early mover

As a strategic investor, IQT works with companies to enhance their technology with a view to government agency testing and use within 12-24 months. Investments typically range from US$500,000 to US$3 million and involve multiple government partners. Companies obtain financial resources, market understanding, engineering expertise and access to government partners. In the process, private sector investors are alerted that a company has potential to deliver national security capabilities. Over more than 20 years, IQT has made more than 500 investments. Roughly three quarters of these investments have been field-tested by US government partners, and approximately 50 per cent have been adapted for use.

By 2000, the federal government’s share of total R&D funding in the United States had fallen to 25 per cent.43 While defence-related R&D continued to account for more than half of all federal R&D spending, by the mid-2000s private industry accounted for more than 70 per cent of total US R&D expenditure. Of this amount, 76 per cent was development, 20 per cent was applied research, and only 4 per cent was basic research.44 The rise of the ‘Big Tech’ platforms and US leadership in the digital economy tended to overshadow the strategic implications of the far-reaching transformation of innovation in the United States. As one 2022 study observed from an historical perspective:

Following WWII, the United States seized a lead in advanced technologies by under - standing and leveraging the scientific and industry landscape. Guided by Vannevar Bush’s vision in “The Endless Frontier”, a knowledge-generating triangle of govern - ment, academia, and industry carried us to the moon, seeded Silicon Valley, and created the internet. Yet, in only a few decades that triangle began to evolve, and the role of government in setting and driving the agenda for new scientific frontiers began to diminish. Silicon Valley and modern venture capital grew into a force of its own. More recently, the information age opened the door to a fifth player – “the crowd” – that has bolstered individualized capacity to provide sources of funding and driven new research outside of traditional institutions. The innovation has changed, but thus far America has not fully adapted.45

China’s rapid economic and technological development and its accelerated integration into the global economy in the early 21st century both reinforced the relative decline in manufacturing’s share of the US economy and deepened its integration into global value chains. The return of great power competition to the centre of US national security strategy in the second decade of the 21st century brought with it heightened concern about a military force that could no longer claim unsurpassed technological superiority.

By the mid-2010s, a growing number of US defence strategists came to appreciate both the scale of the challenge posed by China’s newly acquired military capability and the extent to which the eclipse of the old government-centric national innovation system exposed the United States to greater strategic vulnerability. The dual quest to accelerate the Pentagon’s adoption of commercial technology and strengthen the US national security innovation base led former US Defense Secretary Ash Carter to establish the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) in 2015. In partnership with other Pentagon agencies, the DIU was designed to act as a bridge between US Defense and the commercial technology sector. It is now possible to point to a proliferation of defence innovation labs, hubs and centres across various arms of the US defence enterprise following the creation of the DIU.46

DIU provides Pentagon-wide focus on commercial technology

A primary goal of the DIU is to shorten the procurement cycle through rapid prototyping, piloting and iterative development that quickly evaluates technologies for military application. With offices in Silicon Valley, Boston, Austin, Chicago and inside the Pentagon, DIU teams aim to deliver scalable revenue opportunities with commercial vendors within 12 to 24 months. Companies the DIU has backed have been awarded around US$5 billion in contracts from US defence agencies.

In recent years, the DIU has been joined by a proliferation of new players across various arms of the US military. One study identified more than 60 defence innovation organisations as part of the DoD innovation ecosystem. As well as DoD-wide organisations like DARPA and the DIU, specific bodies under the umbrella of the Services include: Army Applications Lab, Army Research Lab and XTechSearch (Department of the Army), CNO Rapid Innovation Cell, NavalX, and Marine Corp Rapid Capabilities Office (Department of the Navy), and AFWERX, AF Ventures and Air Force Rapid Capabilities Office (Department of the Air Force).

The Trump administration’s 2018 National Defense Strategy (NDS), as well as formalising a shift in the focus of US defence planning from terrorism to great power competition, highlighted the way rapid technological advancements were changing the character of war. It drew a direct line between many technological developments coming from the commercial sector, expanding to more actors with lower barriers to entry, and the erosion of the “conventional overmatch” to which the US military had grown accustomed.47 The Biden administration’s 2022 Defense Strategy represents a further evolution of this thinking around accelerated force development and incorporating new technology more quickly. The Strategy outlined a layered picture of US technology investment priorities.

We will fuel research and development for advanced capabilities, including in directed energy, hypersonics, integrated sensing, and cyber. We will seed opportunities in biotechnology, quantum science, advanced materials, and clean-energy technology. We will be a fast-follower where market forces are driving commercialization of military-relevant capabilities in trusted artificial intelligence and autonomy, integrated network system-of-systems, microelectronics, space, renewable energy generation and storage, and human-machine interfaces.48

Implicit in this approach is the recognition that the Pentagon no longer has the sort of policy reach it used to command in the development and application of cutting-edge technologies. The technology leadership of the United States in what President Biden calls, the “decisive decade” for global geopolitics will require the mobilisation of a much broader network of private sector actors within the US defence-finance-tech ecosystem.

Bridging the Valley: Military modernisation in a transformed innovation system

A comparative assessment of corporate R&D expenditure highlights the challenge defence planners confront in nudging the contemporary US innovation system towards areas of military priority. The five Big Tech giants combined – Amazon, Alphabet, Microsoft, Apple and Meta – spent an estimated US$127 billion on R&D in 2020. The equivalent combined R&D expenditure of the top five US defence contractors – Lockheed Martin, Raytheon, General Dynamics, Boeing and Northrop Grumman – was estimated at just over US$8 billion, less than seven per cent of Big Tech’s R&D footprint.49

The divide between the US military’s technological demands and the centre of gravity of the US innovation system can be seen through the prism of three related challenges. The first is the type of financing model – VC – that plays such a central role in the system. The second relates to the technology incentives that are most lucrative to innovative firms from a commercial perspective. And the third concerns persistent obstacles and gaps that limit the capacity of Pentagon agencies to facilitate adoption of new technologies into the hands of warfighters.

The VC investment model encapsulates the different perspectives and incentives between how the United States creates new technology based on commercial imperatives and the national security architecture. The growth cycle of start-ups, with their high-risk/high-reward, scale-up-quickly mindset and constant search for additional capital to continue existing, is not well aligned with the military’s low-risk, deliberative approach to developing, testing and integrating technologies where the focus is on reliability and performance. Divergence in risk appetites, timelines and ultimate objectives makes aligning government and private sector incentives a major challenge as this summary of the VC investment model makes clear. As assistant professor of history at Georgetown University, Jamie Martin, explains:

The aim of venture capital is to bet on the long tail: Invest in many different start-ups, knowing most will fail but hoping at least one big success will more than offset the losses. For this reason, the business has always focused on technology companies, which offer the greatest potential for fast growth and outsize returns. Most venture capital firms today are located in Silicon Valley, and nearly all the major tech companies, including Amazon, Apple, and Google, relied on venture capital funding to get off the ground. The playbook is simple: Raise capital from institutional investors such as pension funds and university endowments, buy an equity stake in young companies, and then oversee their operations until they go public and investors can cash out.50

This incentive structure is reflected in turn in the sorts of products and services of most interest to private investors. VC firms in the United States have traditionally remained heavily weighted towards digital platforms and consumer technologies – defined by low-cost scalability, low barriers to entry and relatively quick profits. This innovation model places a premium on getting a product out quickly and fixing the bugs later. There is less appetite for costlier (and hence riskier) investments in ‘deep technologies’ such as advanced manufacturing, biotechnology and quantum computing that require significant upfront capital and longer periods to mature and where the emphasis is on working correctly and meeting defined standards from the outset.51

This incentive structure is reflected in turn in the sorts of products and services of most interest to private investors. VC firms in the United States have traditionally remained heavily weighted towards digital platforms and consumer technologies – defined by low-cost scalability, low barriers to entry and relatively quick profits.

Where these incentives and tensions converge from a technology policy perspective is around bridging the so-called “valley of death.” This is defined as the gap in the development, production or successful fielding of a technology based on a demonstrated degree of technological readiness. Based on the traditional Technology Readiness Level (TRL)52 scale, it tends to apply to TRL levels five (laboratory testing) and higher. In this context it includes the period of time in which a business is seeking to transition a prototype or commercially available product to a defence contract.53 A detailed study of the US defence innovation system by the RAND Corporation found that while the Pentagon has funding available to support technology development, “much of that funding is concentrated in the early stages of development, and there is limited support for testing and proof-of-concept demonstrations that can help sustain a company.”54 Due to misaligned processes or incentives, many technologies stall in the valley of death without a clear path to continued development or transition. The RAND report concludes that the “biggest gap” in the commercial technology pipeline “is that no one has both responsibility and authority for solving the valley of death and transitioning innovative commercial technology at scale.”55 In short, no one entity owns the entire problem.

The latest attempt by the US Defense Department to address this challenge is the creation within the Pentagon of the Office of Strategic Capital (OSC). Established in late 2022, the OSC’s mission is to connect companies that are developing technologies vital to national security with sources of private capital, recognising that many such technologies “often require long-termfinancing to bridge the gap between the laboratory and full-scale production.”56 Moreover, many critical technologies are not purchased directly by the Pentagon with the result that existing procurement programs struggle to support immediate capital needs for companies specialising in these areas.

Hence, the dual mission of OSC is to identify and prioritise promising critical technology areas and to enlist funding for these technologies, including supply chain technologies not always supported through direct procurement. To achieve this, OSC will partner with private capital providers and other federal agencies to employ investment vehicles that have been successful in other contexts. The objective is to both ‘crowd in’ private capital and to attract patient capital to bring critical technologies to scale.

In summary, the quest within the US Government to adapt to the new geometry of the US national innovation system and bridge the different worlds of defence planners, venture capitalists and tech entrepreneurs remains a work in progress. There is evidence that recent measures are paying dividends. An analysis of dualuse venture fund flows between 2014 and 2018 found strong growth in funding into Pentagon technology priorities, with initial round funding rising from US$5.2 billion to US$14.9 billion over the period and with the defence share of total VC funding tracking at around 20 per cent.57 These trends have strengthened further in the wake of the war in Ukraine, with PitchBook data showing that US venture investment in defence start-ups surged from less than US$16 billion in 2019 to US$33 billion in 2022.58 And, in a break from the past, there are signs of increasing preparedness on the part of large VC firms in the United States to invest in technology that can have kinetic effects.

The success of several dual-use ‘unicorns’59 also points to a dynamic, self-sustaining element to the US defence-finance-tech ecosystem. Successful firms such as Anduril, Palantir, SpaceX, Cloudfare, Tanium and ShieldAI are testimony to the fact that barriers, both incentive-based and cultural, to engagement with the Pentagon are not insurmountable. Factors identified as helping to unlock new contracts for a wider range of defence and dual-use start-ups include the rapid development of AI, greater procurement flexibility in certain areas and enhanced capacity to sell directly to those carrying out specific military missions.60

At the same time, various studies continue to highlight bureaucratic acquisition processes, lack of funding for relevant technologies and firms at key development stages and unfulfilled expectations on the part of various actors in the innovation system.61 Complaints by defence tech startups and bodies such as the Silicon Valley Defense Group continue to surround the Pentagon’s attachment to systems and procedures that favour large incumbents, as well as what some capital providers see as a stubborn unwillingness on the part of defence bureaucracies to understand relevant business models and to take account of commercial objectives.62

Five takeaways for Australia

For Australia, several lessons can be drawn from efforts by the US military to strengthen its innovation ecosystem. Some are suggestive of what Australian policymakers should focus on; others point to what they should temper or seek to avoid. The following summarises five takeaways that could help to inform the development of approaches and tools to be implemented in an Australian context.

1. Strategy must win out

Strategy must inform decision making in technology and acquisition. From a resourcing perspective, the vast bulk of US defence spending is in the domain of ‘big bets’ on major weapons systems. This is widely seen as reinforcing a high degree of status quo bias in Defense Department operational concepts and capability acquisition programs, and established processes, long after new strategic circumstances demand course correction. Hence, the Pentagon’s established technology focus has long been on large platforms capable of locating and destroying adversary hardware at a distance. With its origins in the Cold War, this strategic focus has carried through strongly to today via campaigns in the Middle East and the Balkans in the 1990s and Afghanistan and Iraq in the 2000s, with substantial legacy bias.

For the most part, policy reform proposals tend to focus on institutional failings such as inherent risk aversion, poor communications, rigid contracting processes and inadequate development financing, that can result in costly failures and cause fast-moving technology companies to disengage. Yet there is a powerful case to suggest that, in confronting the new geometry of defence innovation and the changing nature of war, the more fundamental issue is not “that the DoD doesn’t know how to buy; it doesn’t know what to buy.”63

Official Pentagon statements over the past five years all but concede the essential thrust of this critique. The 2018 NDS talked of the United States “emerging from a period of strategic atrophy” where it failed to adapt to a world where rapid technological developments in the commercial sector had changed the character of war.64 The 2022 NDS describes the Pentagon’s force development, design, and business management practices as “too slow and too focused on acquiring systems not designed to address the most critical challenges we now face.” The current orientation, it argues, “leaves little incentive to design open systems that can rapidly incorporate cutting-edge technologies, creating longer-term challenges with obsolescence, interoperability, and cost effectiveness.”65

This underlines the fundamental importance of strategy in defining what to buy when faced with the challenge of military modernisation at speed. Strategy – and the clearly defined functional needs and effects that flow from strategy – are paramount in the development and acquisition of advanced military capabilities within set budget constraints. This point was registered strongly in an Australian context by the DSR; it is the implementation that matters.

2. Leverage your strengths

A positive lesson from the US defence-finance-tech ecosystem is the pragmatic focus on core strengths. However subject to trial-and-error various policy initiatives may be, harnessing existing and emergent strengths is a better strategy than seeking to recreate a more government-centric innovation system characteristic of a bygone era. What tends to unite various initiatives adopted by the Pentagon and military services over recent years is the desire to work with the grain of US business and financial models, commercial imperatives, and innovation drivers to build deeper connective tissue between the national security apparatus and the private sector.

However subject to trial-and-error various policy initiatives may be, harnessing existing and emergent strengths is a better strategy than seeking to recreate a more government-centric innovation system characteristic of a bygone era.

With its extensive network of strong research universities, federal laboratories, deep and sophisticated financial markets, risk-taking and entrepreneurial culture, the United States continues to hold vital cards in the quest for technological advantage. The challenge is to remodel the linkages of the transformed US innovation system to the changing demands of the Pentagon in a way that unlocks the full potential of the US defence-finance-tech ecosystem.

For Australia, the task is similar – to identify and leverage core areas of strength and take advantage of emergent trends in finance, technology and research. As the world’s 12th largest economy with strong governance, deep and sophisticated financial markets, a skilled workforce and highly ranked universities and research institutions, Australia has many of the ingredients needed for a world-class defence-finance-tech ecosystem. A more complex and threatening security environment should provide the impetus to combine these attributes for enhanced military capability.

3. Coordinate, coordinate, coordinate

For a country with the military scale and reach of the United States, quantity can have a quality all its own. Hence, a case can be made that the dozens of military innovation units across the various US defence forces allows for a more dispersed and richer model of experimentation (that is, trial and error) when it comes to applying commercial technologies to military application.

For Australia, however, the lesson is more around what to avoid. Budget constraints and scarce resources suggest no alternative but to prioritise, coordinate and collaborate relentlessly across government and the private sector to the highest degree possible. For example, Australia’s annual defence R&D budget is of the order of US$420 million.66 The US Democrat’s Fiscal Year 2024 budget request for defence research, development, test and evaluation amounts to US$145 billion. Even then, the need to better align US efforts and budgets across defence innovation organisations – based on geographic focus, technology area, and stage of funding – continues to be made.

4. Money matters, but so does culture

While some companies may have ideological reasons for not working with defence institutions, there is growing evidence to suggest there is less than meets the eye on this front. The DIU, for example, has worked with more than 100 vendors that do not usually bid on defence contracts, including many who had never before worked with the Pentagon. “Change the incentives, and the innovators will come” is a reasonable conclusion from the US experience.67 The emphasis in this context tends to be on funding above all else.

Nonetheless, there can be residual cultural factors that work to constrain private sector involvement in the defence enterprise. The mismatch between a risk-averse defence capability acquisition process designed to manage complex, linear weapons acquisition programs in a deliberative way and a private-sector-led innovation system weighted towards moving fast, accepting risk and disrupting established ways of doing things continues to discourage public-private partnerships. Hence cultural problems can impede the adoption of innovative commercial technology for military use.68

Here, DARPA offers useful hints as to the sort of organisational and human resource model that should be contemplated if Australia is serious about reforming its defence innovation. Nearly 100 of DARPA’s roughly 220 government employees are program managers, who oversee approximately 250 research and development programs. DARPA goes to great lengths to identify, recruit and support program managers at the top of their fields. Individuals come from academia, industry, and government agencies for limited stints, generally three to five years. Special statutory hiring authorities and alternative contracting vehicles allow the agency to take quick advantage of opportunities to advance its missions.

The lesson for Australian policymakers is reasonably straightforward. Ultimately, both incentives (money) and culture (people) matter as part of a comprehensive approach to gearing Defence towards more rapid translation of technologies into advanced military capabilities. Encouragingly, Australian Government ministers have given the Defence Department the clear imprimatur and instruction to take risks and do business differently.

Both incentives (money) and culture (people) matter as part of a comprehensive approach to gearing Defence towards more rapid translation of technologies into advanced military capabilities.

5. Innovation and the limits of the org chart

The evolving US defence-finance-tech ecosystem and the wider innovation system in which it operates are testimony to the power of networks in the innovation process. A defining feature of the US national innovation system in the age of Big Tech and VC is its “incremental and distributed nature.”69 As one think tank analyst posited:

It is not linear. Tangled connections are the norm in VCs, since a deep knowledge of the industry is essential. Serendipity plays animportant role when research in one area turns up something of use for another problem. Many firms and institutions are involved, with researchers and entrepreneurs building upon and expanding the work of others.70

This bottom-up, unpredictable element needs to be factored explicitly into policy design. Innovative activity will not arise from a new org chart in the Defence Department. It requires a much more forward-leaning outreach agenda from government designed to shape, attract and scale private investment in defence related innovation activity.

As much as lines of authority, it needs to emphasise the intangible, enabling elements of the policy environment based on the role of networks and the importance of diverse feedback loops. A key feature of the US experience in seeking to identify, develop and apply commercial technologies for military use is its lack of uniformity. There is no single pipeline or pathway of commercial technologies from concept to fielding. Potential paths are neither linear nor sequential and the path an innovative technology, product, or service takes can differ depending on characteristics of the technology and business, financial considerations, and alignment with other US Defense Department processes.71

Actions within the alliance framework

In the context of the Australian-US Alliance, several steps could be taken to join up respective defence-finance-tech ecosystems and harness the lessons and strengths of each.

Firstly, the Australian and US governments should explore how best to draw from US experience leveraging commercial technologies for military application. As an interim step, and short of new institutional initiatives on the part of the Australian Government, a DIU presence in Australia could be established in a manner similar to that of IQT, which has been in Australia since 2018.

Secondly, Australia should look to embed a Defence official with appropriate finance expertise in the US OSC. This would provide a firsthand, real-time window into approaches and tools that are likely to be effective at leveraging patient, private sector capital in technology areas that traditionally have struggled to access adequate finance.

Thirdly, as has been well established elsewhere, reforms to US International Trade in Arms Regulation (ITAR) are essential to a raft of shared technology capability building initiatives – including AUKUS Pillar I and Pillar II. This requires action at both the US executive and congressional levels as well as reforms to Australian procedures to ensure harmonisation of export controls.72

Fourthly, Australia and the United States could better leverage the commercial solutions and supply chains that exist in each country. Partly, this will be addressed via the AUKUS partnership, along with the United Kingdom. But there is wider opportunity for Australia, the United States and their allies and partners to scope solutions across each other’s national defence industry and pool experts for shared, labour-intensive tasks such as unsolicited defence innovation proposals.

Australian Government defence innovation and SME growth initiatives have been insufficient

Australia’s size and capacity is substantially different to the United States, meaning Australia’s output will never approach the same scale or be of the same character. However, having to do more with less can lead to favourable outcomes and Australian scientific ingenuity has produced world-leading defence technologies in the past. Australia’s development of radar technology, for example, is outstanding and has resulted in its export to the US military.73 Developed in the 1970s and 80s, Australia’s high-frequency over the horizon radar (OTHR) and related Jindalee Operational Radar Network (JORN) have been described as Australia’s technological crown jewel.74 Australia’s national defence industry also has global comparative advantages in quantum computing, acoustics and biotechnology.75

Although Australia has shown great capacity to create and innovate in recent decades, Australia’s government-led defence innovation initiatives have had limited success and Australian industry is yet to be fully leveraged in support of the national interest.

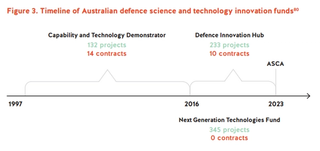

Australia’s publicly funded hub for defence innovation is DSTG within the Defence Department. DSTG has an annual budget of around A$408 million, making it the second highest publicly funded research institution in Australia after the CSIRO.76 DSTG has prioritised developing technologies ranging from cyber warfare, to spacebased and undersea surveillance, to quantum positioning, navigation and timing.77 Since the 1990s, DSTG and Defence more broadly have overseen initiatives to spur innovation in partnership with Australian industry and more quickly transition technologies into Defence capability. Primary among these has been the Capability and Technology Demonstrator (CTD) program, later renamed the Defence Innovation Hub (DIH) and the Next Generation Technologies Fund (NGTF). DIH was targeted at later stage capability development while NGTF was focused on early-stage research.78

The CTD, then later DIH and NGTF did not result in enough new military capability or export opportunities to be considered successful programs. Concerns have been raised by some industry executives about the DIH and NGTF investment frameworks. While not fully representative, some within the private sector believe the frameworks skewed official decision makers towards more evenly distributing innovation funds across Australian companies as opposed to deliberately selecting companies with the greatest chance of success or most valuable offering to Defence.79 Defence’s reluctance to ‘pick winners’ and instead spread the resources more thinly across multiple companies had the effect of limiting the success any one company could enjoy. Rather than completing 10 years of operation out to 2026, DIH and NGTF projects and funding have been rolled into ASCA.

Clearly, the Australian Government and industry has concerns about the effectiveness of the nation’s defence innovation system. Citing Defence’s innovation system “not performing as well as intended” and calls from industry for it to be overhauled, the Australian Government commissioned an independent Defence Innovation Review in 2021.81 A public version of the review was released in March 2023, however the findings were heavily redacted.82 Although the findings are unclear, industry’s concerns provide an insight into what the review might have concluded. In particular, Australian innovators and companies assert they are impeded by inconsistent and opaque processes, complex contractual requirements, and frequent changes to requirements by government.83

To address the underperformance of previous initiatives and spur new defence innovation, while in Opposition, the Labor party proposed an Australian version of DARPA.84 Originally this initiative had the working title of ‘Advanced Strategic Research Agency’ and was intended to support AUKUS through working with DARPA and the UK Advanced Research and Invention Agency (ARIA) to fund breakthrough technologies.85 After Labor won office in 2022 however, the concept evolved and expanded beyond an organisation modelled off DARPA to a more all-encompassing model, now represented in the Advanced Strategic Capabilities Accelerator (ASCA). The change in name is significant. Rather than defence research and innovation – as DARPA and ARIA are tasked – ASCA is seeking to transition technology solutions into the hands of Australian military personnel at speed.86 The Defence Department’s intention is for the hub of defence innovation to remain within DSTG and not in a separate institution.

The Advanced Strategic Capabilities Accelerator: Australia’s new effort for speed to capability

ASCA launched on 1 July 2023 and has been allocated A$3.4 billion over 10 years, which is a considerable amount considering DSTG receives A$408 million annually.87 ASCA’s funds are being sourced from within the Defence portfolio through subsuming DIH and NGTF funding and other offsets. During its initial 18-month operating period, ASCA has committed to consider technology solutions across the TRL spectrum – from low TRL technologies at the basic discovery level to high TRL technologies that are ready to be tested and operationalised. In private, Defence officials describe ASCA has having responsibilities similar to three US agencies: DARPA, DIU, and the Strategic Capabilities Office.88

Given ASCA is commonly equated with DARPA and the fact DIH and NGTF programs are being subsumed by ASCA, it is understandable the expectation from Australian industry and external observers is that ASCA is itself intended to create new technologies and innovate. Instead, ASCA is attempting to rectify the shortcomings of the DIH and NGTF which stumbled at the last hurdle – the actual translation of technology and innovations into defence capability. ASCA is being asked to identify and pull through asymmetric innovations into Defence capabilities in priority areas like hypersonics, directed energy, trusted autonomy, quantum technology, information warfare, and long-range fires. This leaves Australia without an exact DARPA equivalent.