On Line Opinion

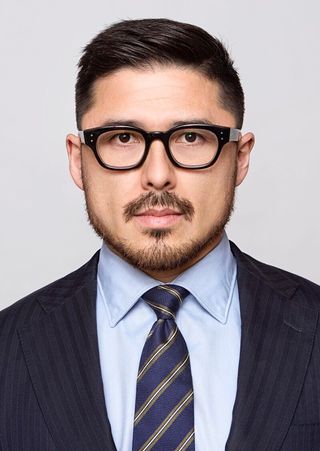

By Malcolm Jorgensen

A striking feature of recent Cold War style confrontations between Russia and the United States is the frequency with which plainly political motives have been contested through the rubric of international law. In 2013 President Vladimir Putin warned against unauthorised US intervention in the Syrian Civil War by asserting "the law is still the law, and we must follow it whether we like it or not." In return President Barack Obama has condemned Russia's occupation and annexation of Ukraine's Crimean peninsula as "violations of international law."

The territorial integrity of all states is protected under international law, subject to narrow exceptions where military force is authorised by the United Nations Security Council, or as an act of self-defence. The right of a population to declare secession from their existing state is restricted further, and certainly excluded where achieved through an illegal use of force. Both America's proposed Syrian intervention and Russian actions in Ukraine fall outside accepted law. Yet in each case the offending state insists law is on its side.

This begs the question of why judging illegality even matters if this fails to prevent states bending law to serve political interests. International jurist Martti Koskenniemi famously warned that international law is frequently reduced to either an irrelevant description of utopia, or merely an apology for power. To be consequential international law must remain relevant to powerful states, and yet be capable of mitigating the excesses of naked power.

Putin well understands the clout of legal rhetoric, having written his final undergraduate thesis on international law. In 2013 he grandly declared that his interest in opposing US action was "not protecting the Syrian government, but international law." This was utterly implausible where Russia had interests in protecting a key regional ally and opposing US influence. The legal challenge nevertheless served to preserve legal doctrine as a bulwark against naked power.

Obama's former international legal advisor Harold Koh argued that circumstances in Syria enlivened a right to engage in "humanitarian intervention" beyond established legal exceptions. Notwithstanding the assertion of "well-meaning" intentions, this interpretation would grant powerful states the right to legally employ military force on their own say so. This is incompatible with international law as an effective constraint on unchecked ambition and was ultimately abandoned.

Positions are now reversed in Ukraine, with Russia forced to defend actions taken outside of established law. Arguments have variously claimed that intervention was authorised by the "legitimate president" of Ukraine, and that a "humanitarian" duty exists to protect the majority ethnic Russian population in Crimea with whom there are "historical and cultural ties." The referendum in which this population overwhelmingly voted to join the Russian Federation was defended as a "right of self-determination." None of these arguments withstand scrutiny.

In the first case only a leader with effective control over the country can authorise foreign intervention. Putin himself acknowledged that deposed President Viktor Yanukovych has "no political future." In the second case the right to broaden self-defence to include one's own national or ethnic compatriots is not an accepted interpretation of international law. The claim by residents to then unilaterally gift territory to Russia on the foundation of such illegality is not a valid expression of self-determination, and the purported annexation is without legal effect.

The Russian legal case is nevertheless one with a long-established pedigree. The "Brezhnev Doctrine" was first articulated by the then Soviet premier as a gloss on international law to justify the 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia. Brezhnev asserted a right to extend "military aid to a fraternal country" in circumstances where internal forces have created "a threat to the security of the socialist community as a whole."

The Soviet and now Russian conception of international law appears to be that territorial integrity yields to an inherent right to intervene within its historical sphere of influence. In the modern incarnation socialist solidarity is replaced by the notion of an indivisible Russian people transcending national boundaries. This gloss was used to justify Russia's otherwise illegal 2008 military intervention in the former Soviet republic of Georgia.

Acquiescing to this legal interpretation grants Russia the authority to define self-defence so broadly that the independence and sovereign equality of all former Soviet republics is rendered meaningless. This wouldindeed be the debasing of international law to a mere apology for Russian claims over the vestiges of empire.

The value of international law is that it forces states to defend their actions not in terms of parochial outcomes, but by reference to general principles serving interests of the many. In both Syria and Ukraine, novel legal arguments can be rejected because they arrogate legal power in precisely the circumstances when law is needed to oppose unchecked power.

Upholding a clear interpretation of legality matters because it maintains an authoritative agreement on what constitutes an impermissible threat as Russia further encroaches on Ukrainian sovereignty. It is disingenuous for any state to appeal to doctrines of international law as being above politics. Rather the legal contest over Crimea is part of an ongoing battle to sustain the integrity and justice of international law.

This article was originally published at On Line Opinion