Key takeaways

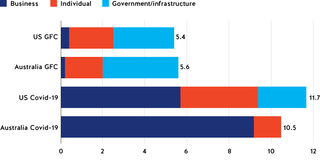

- Governments in both Australia and the United States are spending twice as much to soften the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic as they spent in packages following the global financial crisis, with extraordinary budget assistance exceeding 10 per cent of GDP.

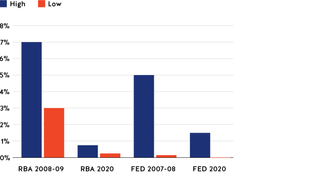

- Monetary policy has much less scope to offset the contraction than in 2008-9 when central banks in both Australia and the United States were able to slash rates by at least 4 per cent. This time, the maximum rate cuts have been just 0.5 per cent in Australia and 1.5 per cent in the United States.

- The two crises are very different: in 2008-9, financial markets were disrupted and business and consumer confidence was shattered whereas in 2020, there has been a government-ordered shutdown of consumer-focussed business. Stimulating demand would not make any difference now.

- Despite differences in political systems, both Australia and the United States have focussed emergency packages on helping businesses to survive the loss of sales and assisting those who have lost their jobs. There has been none of the “shovel-ready” infrastructure programs that were used following the financial crisis.

- The budget spending this time is concentrated over the next 12 months whereas following the financial crisis, spending stretched over four years. There may be pressure for further stimulus spending if the recovery in employment takes longer than expected.

Introduction

Both the Australian and United States governments are spending about twice as much to soften the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic as they invested in fiscal packages following the global financial crisis.

The big increase in budget spending reflects both the immediate impact of government-forced business shutdowns, and also the limited scope for monetary policy to offset the contraction.

Budget spending is much more concentrated, with the large majority of the investment occurring over the next 12 months, whereas the focus on infrastructure following the 2008-9 crisis stretched the major outlays over four years in both countries.

Many economists and government officials are hoping for a “v-shaped” economic recovery after the virus passes, enabling the withdrawal of government support, however it is possible that further stimulus packages will be developed if economic activity remains depressed.

The spending is equivalent to 10.5 per cent of GDP. This compares with the Rudd government’s outlays of 5.6 per cent of GDP in a series of packages in the wake of the 2008 collapse of Lehman Brothers.

In Australia, federal government budget support has now reached A$210 billion.1 This sum does not include either the A$90 billion concessional loan facility for small and medium business established by the Reserve Bank or the small business loan guarantees of up to A$20 billion, neither of which will appear as budget spending.

The spending is equivalent to 10.5 per cent of GDP.2 This compares with the Rudd government’s outlays of 5.6 per cent of GDP in a series of packages in the wake of the 2008 collapse of Lehman Brothers.

In the United States, the budget intervention has also been more forceful. The US$2.3 trillion (A$3.8 trillion) package passed by Congress on 27 March followed earlier interventions totalling US$200 billion, with the total equivalent to 11.7 per cent of GDP.3

Following the financial crisis, the Obama administration implemented a US$780 billion stimulus package, equivalent to 5.4 per cent of GDP.4 This does not include the US$700 billion Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), legislated by the George W. Bush administration in the immediate aftermath of the Lehman Brothers collapse, which was designed to bail out failing financial institutions. Most of the TARP funds were ultimately recouped by the US government, with a final cost of US$31 billion.5

A government-ordered collapse

The two crises are very different. The global financial crisis was caused by a shock to the financial system. It shattered both business and consumer confidence and disrupted financial intermediation as many financial markets froze and banks absorbed large losses.

Governments did not know how bad it would become but believed they could counter the downturn with programs to stimulate employment and demand. In the United States, unemployment rose from 6 per cent in September 2008 to 10 per cent a year later.6 The rise in unemployment in Australia was much more subdued than expected, increasing from 4 per cent in August 2008 to a peak of 5.9 per cent by June 2009.7 This reflected Australia’s relative success in avoiding a recession.

The COVID-19 crisis has resulted in a government-ordered shutdown of large sections of the consumer economy. It is not a question of stimulating demand — supply has been forced to close. Sections of the economy that are still able to operate are suffering from the lost demand from the sections that are not. The challenges for government are to encourage business to retain staff in the face of disappearing sales, to help those businesses that have had to shut operations to fend off bankruptcy until the crisis is over and to support those who have lost their jobs.

The forced suspension of spending on restaurants, entertainment, travel, clothing and a wide range of household services including education has resulted in an immediate and severe economic contraction.

Governments hope that this intervention may prevent the wholesale destruction of businesses and widespread corporate and consumer debt default, which would leave economies depressed long after the virus has been controlled.

Australian household spending is 55.5 per cent of Australia’s GDP, which is slightly below the advanced country average of 60 per cent, while the United States is above average at 68 per cent.8 The forced suspension of spending on restaurants, entertainment, travel, clothing and a wide range of household services including education has resulted in an immediate and severe economic contraction.

Early evidence of the scale of the collapse in the United States is the 10 million people filing for unemployment benefits in the last two weeks of March. In Australia, the system for processing unemployment and social security applications, which normally handles a load of around 5,000 concurrent users, crashed with more than 100,000 seeking help at once.

Monetary policy response

When the global financial crisis struck, the first and, arguably, most forceful response came from the central banks.

In the United States, trouble with “sub-prime” mortgages started roiling financial markets in late 2007 and the Federal Reserve responded by cutting rates. Between August 2007 and April 2008, the US Federal Funds rate was cut from 5 per cent to 2 per cent.9 Following the failure of US investment bank Lehman Brothers, it was lowered further to 0.15 per cent, while a program of buying mortgage-backed securities began in November 2008 and was expanded to bank debt and Treasury bonds, with the objective of lowering medium and long-term rates, while injecting liquidity into the economy. By March 2009, the Fed held US$2.1 trillion in securities.

Both the Australian and US central banks have deployed quantitative easing measures and flagged they can do more, but have reached the limit of what they can do with their influence over short-term rates.

Australia’s economy was still showing signs of overheating in early 2008 in response to the resources boom and the Reserve Bank was lifting rates. However, between October 2008 and April 2009, the Reserve Bank was able to cut its cash rate from 7 per cent to 3 per cent.10 By April 2009, it was apparent that the Australian government’s budget stimulus measures were having an effect and the Reserve Bank did not see the need to cut further (indeed it was raising rates again by October 2009).

Whereas the Fed was able to deliver almost 5 full percentage points of monetary easing in 2007-8, while the Reserve Bank cut its rate by 4 percentage points, this time only small moves have been possible. In the United States, the Fed cut its benchmark rate by 0.5 per cent on 3 March and again by 1 per cent at an emergency meeting on 15 March, which brought rates down to zero. In Australia, the Reserve Bank cut rates by 0.25 per cent on 3 March and again by the same amount at an emergency meeting on 18 March, bringing its rate down to 0.25 per cent.

Both central banks have deployed quantitative easing measures and flagged they can do more, but have reached the limit of what they can do with their influence over short-term rates. Australian Reserve Bank Governor Philip Lowe has ruled out sending rates negative.11 This has left government with the major responsibility for economic support.

Figure 1. Monetary policy response in Australia and the United States

Emergency packages

In both countries, the composition of the emergency budget support to the COVID-19 crisis is different to the GFC response, with much greater emphasis on helping businesses survive and little of the artificial job creation through infrastructure spending that was at the heart of the 2008-9 stimulus programs. However, the GFC demonstrated the fiscal firepower that could be marshalled by a determined government, establishing the precedent that is being followed now.

The budget policy decision-making processes are very different in Australia and the United States and this has an impact on the shape of the policy support. Emergency economic policy in Australia is decided in a concentrated group led by the Prime Minister, Treasurer and Finance Minister and the heads of their respective departments. The emergency nature of the intervention leaves little scope for ministers in other portfolios to contribute, and there is heavy reliance on the technical expertise of Treasury in the final design. The Australian government presents parliament with a final set of measures with little scope for amendment.

The GFC demonstrated the fiscal firepower that could be marshalled by a determined government, establishing the precedent that is being followed now.

In the United States, the policy response is much more intensely negotiated between the White House and the leaders of the Republicans and Democrats in both the Senate and the House. In the latest US$2.3 trillion package, many of the details were worked out in four bipartisan committees before Republican Senate leader Mitch McConnell tried to take charge of the final design.

It culminated in several fraught days of filibusters and deadlocks with private talks between Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin and Democrat Senate leader Chuck Schumer delivering the final breakthrough in the early hours of the morning on 25 March.

In the process, the bill expanded from US$1 trillion originally conceived by the White House to US$2.3 trillion, with separate allocations for many favoured causes from each party. US media outlet Politico reports that at one stage, the Republicans wanted funding for a sexual abstinence program while the Democrats wanted limits on greenhouse gases and strengthened union bargaining power.12 An ultimately rare unanimous Senate vote in favour shows both sides got most of what they wanted.

In both the United States and Australia, there has been a succession of emergency responses, as the scale of the challenge became clearer.

Australia’s first A$17.6 billion package was announced on 12 March, the day the World Health Organisation declared the COVID-19 outbreak to be a pandemic. It included a one-off payment to income support recipients and investment allowances and cash grants for small and medium business. There was also a subsidy for apprentice and trainee wages.

This was followed by a decision that Treasury’s financing arm, the Australian Office of Financial Management, would purchase A$15 billion of securities, injecting liquidity in the wholesale financial markets used by small banks and non-bank lenders. This was a strategy lifted from the GFC, when the AOFM supported mortgage-backed security markets.

Figure 2. Emergency budget spending in Australia and the United States, % of GDP

A further package of measures totalling A$65 billion was announced on 22 March, including further one-off payments to income support recipients, an enhanced unemployment benefit and more grants to support small business cash flow. The government announced it would guarantee half bank lending to small business up to A$40 billion (giving it a maximum exposure of A$20 billion) while the Reserve Bank had created a A$90 billion facility for banks to use for secured lending to small business.

The biggest Australian initiative has been the direct wage subsidy of up to A$1,500 a fortnight per employee for businesses suffering large falls in turnover. This initiative, announced on 30 March, is delivered through businesses, but is ultimately a form of employment benefit for individuals. It followed the precedent set by a number of European governments, including the United Kingdom.

The biggest Australian initiative has been the direct wage subsidy of up to A$1,500 a fortnight per employee for businesses suffering large falls in turnover.

The United States started with additional health funding and a surprise boost to international aid on 6 March. This was followed a week later by a package of measures aimed at alleviating hardship for families suffering from the loss of employment, including emergency paid sick leave, expanded unemployment benefits and easier access to Medicaid services and food stamps. The US Congressional Budget Office, a nonpartisan body that provides budget and economic information to Congress, estimated the cost at US$192 billion.

Within days, it was clear more would be required. The final package, ultimately legislated on 27 March, included about US$590 billion in support for individuals, including one-off cash payments, increased unemployment benefits and welfare benefits such as food stamps, US$510 billion for loans and advances to big business, US$377 billion in grants and loans for small business, US$340 billion for state and local governments and US$153 billion for public health.

Australia has yet to see federal spending analogous to the US support for states, which are facing increased demand for health and welfare services. The US package included US$13 billion for schools and US$14 billion for higher education, neither of which have yet received any additional funding in Australia. Australia’s universities will require help having lost much of their revenue base through international students. In an Australian context, these needs would be more likely to be met through normal budget funding processes than in an emergency economic package. The Australian government has provided an additional A$5.4 billion specifically for health and hospitals.

Both the US and Australian responses included permission for individuals to tap their retirement savings, with Australia setting a limit on withdrawals of A$20,000 and the United States, US$100,000. Australian authorities estimate this could yield A$27 billion of additional household income, while superannuation officials suggest the final figure could wind up twice as high.13

The big difference between the responses to the COVID-19 crisis and the GFC is the absence this time of infrastructure programs intended to generate employment.

Australia’s emergency response also includes measures intended to assist in business survival without carrying a fiscal cost. These include exemptions on “responsible borrowing” codes imposing extensive due diligence for lenders to small business, providing a safe harbour for directors of companies that may be trading while insolvent, and a proposed six-month ban on evictions for both commercial and residential tenants.

The big difference between the responses to the COVID-19 crisis and the GFC is the absence this time of infrastructure programs intended to generate employment. During the financial crisis, there was a focus on “shovel-ready” construction projects which could be commenced rapidly including, in Australia, the school refurbishment program as well as social housing. Both Australia and the United States ran home-insulation schemes. In the face of the immediate closure of business, even “shovel-ready” projects would not start quickly enough to assist.

More may be needed

In both Australia and the United States, spending is intended to be short term, mostly occurring in 2020 and lasting no longer than through to the middle of next year.

During the financial crisis, the maximum impact of the stimulus spending on the budget balance was, for Australia, 2 per cent of GDP in 2008-9, and for the United States, 2.6 per cent of GDP in 2009. By 2012, spending had dropped to 0.6 per cent of GDP in Australia and 0.2 per cent in the United States.

This time, the direct impact of the emergency spending on the budget balance in Australia will be roughly 5 per cent of GDP both this year and in 2020-21, while in the United States, about three quarters of the budget impact will be in the current fiscal year, ending in September 2020.

In both Australia and the United States, the impact of the debt required to fund the additional spending will be manageable at around 10 per cent of GDP. In Australia, net government debt had been expected to peak at 21 per cent of GDP this year.14 The addition of a further 10 per cent of GDP to fund new subsidies would still leave Australia’s debt at less than half the OECD average of 75 per cent.

The addition of a further 10 per cent of GDP to fund new subsidies would still leave Australia’s debt at less than half the OECD average of 75 per cent.

The United States goes into the crisis with government debt equivalent to 94 per cent of GDP compared with 45 per cent ahead of the financial crisis. While this leaves less scope, the global demand for US Treasury bonds remains strong.

The emergency packages are likely to cost the budget less than the impact of higher welfare spending and lower tax revenue (known as the ‘automatic stabilisers’), which will push government debts considerably higher.

While the emergency measures have been cast as temporary, there is likely to be some continuing pressure to extend them, even if the direct virus impact is relatively short-lived. Despite the government’s efforts, there will be some permanent destruction of businesses and lasting unemployment. Australian authorities will be under pressure to permanently increase the unemployment benefit. The decision to make child care free for the next six months may also be difficult to reverse.

It is likely that once the virus is under control, it will take time before the consumer economy is allowed to return to full strength, with the resumption of entertainment, tourism and hospitality industries. There could be pressure on governments in both Australia and the United States to follow up their immediate response to the crisis with longer-term stimulus measures that may more closely resemble those that were launched in February 2009.