Executive summary

- China’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 was an important element of its growing integration into the world economy, as well as its domestic economic reform program dating back to 1978.

- In terms of access to US markets, accession only served to make permanent access China enjoyed since the 1980s.

- “China shock” literature highlights the number of US manufacturing jobs lost to import competition from China in previous decades.

- However, a broader assessment of the economic impact of the “China shock” suggests it has been a net positive for the US economy.

- US policymakers are increasingly critical of the role of the World Trade Organization and its failure to discipline China’s trade and industrial policies, but Australian policymakers see G7-led WTO reform as a key element to push back against China’s coercive economic diplomacy.

- President Trump’s trade war and sanctions against China led Chinese elites to equally question the extent of economic interdependence with the United States. President Xi Jinping revived the Maoist concept of “self-reliance,” explicitly citing the rise of foreign unilateralism and trade protectionism as a motivation.

- Far from calling out and disciplining China’s behaviour, President Trump’s trade policies, maintained by the Biden administration, have encouraged China to double-down on its state-led development model and strategic industry and trade policy, while potential multilateral solutions and processes have been neglected and under-utilised.

- The growth in discriminatory trade measures among G20 economies since the global financial crisis in 2008 demonstrates that the problems in the multilateral trading system are not specific to China.

- A key to restoring domestic political support for US leadership of the multilateral trading system is to reframe that leadership in terms of strategic competition with China around the rules and norms of the global economy.

- Effective US leadership of the multilateral trading system would not only promote US foreign policy objectives such as prosecuting its strategic competition with China but would also discipline US domestic economic policy in ways that better serve its economic interests. It also provides a rules-based framework to manage trade frictions arising from climate mitigation under the Paris Agreement and growth in the digital economy.

Introduction

“Twenty years ago, by granting WTO membership, the world gave the Chinese Communist Party a blank check to break its market promises and cheat American workers, while exploiting its own workers. As I predicted then, this decision was an economic failure for our workers and a moral failure for our values.”

Nancy Pelosi, Speaker of the US House of Representatives, Twitter post, 11 December 2021

“The damage that decision [admitting China into the WTO] has inflicted on our families, communities and country is almost incalculable. Instead of exporting ‘economic freedom,’ what we exported was our industrial strength. And the result has been an economic, social and geopolitical disaster.”

Senator Marco Rubio, Inaugural Henry Clay Lecture in Political Economy, 8 December 2021

In the 20 years since China’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, China’s role in the world economy has grown enormously but has also become increasingly contested. As suggested in the opening quotes, there is a bipartisan view in the United States that its support for China’s WTO accession was an economic and strategic error. The 2018 Report to Congress on China’s WTO Compliance by the Office of the US Trade Representative declared it “seems clear that the United States erred in supporting China’s entry into the WTO on terms that have proven to be ineffective in securing China’s embrace of an open, market-oriented trade regime.”1

By contrast, Australia remains a strong supporter of the WTO and the multilateral trading system. Prime Minister Scott Morrison “has called on G7 nations to support reform of the WTO, arguing it would be the best way to blunt Beijing’s campaign of economic coercion against Canberra and to counter Chinese competition in the Indo-Pacific region.”2 According to Morrison, “the most practical way to address economic coercion is the restoration of the global trading body’s binding dispute settlement system. Where there are no consequences for coercive behaviour, there is little incentive for restraint.”3 It remains incumbent upon Australian policymakers to bring their US counterparts closer to the Australian view. This report suggests some of the ways in which Australia, and those in the United States still supportive of the role of the WTO, can make their case.

The re-internationalisation of the Chinese economy, beginning in the late 1970s, yielded enormous economic benefits for China and the rest of the world. China’s formal entry into the rules-based multilateral system from 2001 was widely expected to cement China’s domestic economic reforms and provide incentives for China to become a ‘responsible stakeholder’ in the international system.4 It was hoped, although not necessarily assumed, that greater economic engagement with the rest of the world would lead to bottom-up social liberalisation and greater pluralism, even if expectations for top-down political liberalisation on the part of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) remained low.5

Today, by contrast, China’s role in the world economy is seen as increasingly problematic. China’s entry into the global economy and accession to the WTO is thought by many to have inflicted a negative shock to the US economy which fed the rise of populist politics. The WTO has seemingly failed to discipline China’s illiberal trade practices and market-distorting industrial policies, with the CCP embracing a state-led economic development model with renewed vigour. The WTO now must intermediate between the world’s two largest economies in an environment of growing strategic competition rather than economic engagement.

The rules-based liberal international order is at risk of giving way to a geoeconomic order that elevates strategic competition and state power over international economic cooperation.

The negative assessment of the role of China in the world economy on the part of many in the United States is matched by a similarly negative reassessment of economic interdependence on the part of the CCP. China’s elites have increasingly come to view economic engagement with the United States as a threat to their own power and influence. The Trump administration’s trade and sanctions policies directed against China highlighted its economic vulnerability and encouraged the CCP to double-down on a state-led, domestic economic development strategy focused on greater economic self-sufficiency and global technological leadership. Xi Jinping revived the Maoist concept of ‘self-reliance,’ explicitly citing the rise of foreign unilateralism and trade protectionism as the motivation.6 Increased political and economic suppression in China under Xi Jinping, while mainly driven by internal politics, also reflects CCP perceptions of the dangers posed by foreign economic influence and international economic interdependence, especially with respect to the United States. The rules-based liberal international order is at risk of giving way to a geoeconomic order that elevates strategic competition and state power over international economic cooperation.7

In this report, I evaluate some of the widely held assumptions about the implications of China’s reintegration into the world economy; the “China shock” to the US economy; the supposed failure of US economic engagement with China; and the role of the World Trade Organization. In particular, I argue that the “China shock” delivered net benefits to the US economy and that the regional and sectoral variation in its effects point to US institutions and public policy playing a key role in intermediating that shock. A mostly positive globalisation shock, of which the “China shock” was one symptom, has since given way to a deglobalisation shock due to the 2008 Global Financial Crisis and the 2020 coronavirus pandemic, but also a retreat from international economic engagement by US and Chinese policymakers. In retrospect, the early-mid 2000s appears to be the high point of both US international economic engagement and globalisation.

The case for reforming the WTO is not limited to the fact it has failed to deal effectively with China. While China is the bigger offender, the multilateral trading system has been undermined by a growing resort to discriminatory trade policies by G20 economies more generally. This in turn has compromised the ability of the system to deal effectively with China.

These developments argue for renewed US leadership of the rules-based liberal economic order as a key element of successful strategic competition with China, built around trade expansion with allies and with the World Trade Organization as an important discipline on Chinese behaviour in the world economy. Key to this engagement is a reformed WTO that can serve as a discipline on deglobalisation impulses arising from US domestic politics and the temptations of strategic industrial and trade policy informed by geoeconomic conceptions of strategic competition. The WTO also has a critical role in providing a rules-based framework for climate change mitigation efforts and protecting the fast-growing digital economy from digital protectionism. An important challenge for Australian policymakers is to bring their US counterparts closer to the Australian position on these issues.

Did US economic engagement with China fail?

The evolution of US strategy towards China from engagement to strategic competition and rivalry is conditioned on a widely held view that past economic engagement with China has failed. It is widely thought that China’s apparent rejection of many of the norms of the rules-based liberal order and failure to progress in terms of domestic economic reforms and political liberalisation has invalidated an engagement strategy built on greater economic integration. The more serious charge against engagement is that these failures were foreseeable outcomes that should have been anticipated by the US strategic policy community.

These failures are seen to have given China a leg-up economically at the expense of the United States, weakening its strategic position in the context of what should have been understood as long-term strategic competition. This view is perhaps best exemplified by Kurt Campbell and Ely Ratner’s “The China Reckoning,” an influential 2018 essay in Foreign Affairs.8 Both Campbell and Ratner now hold key positions in the Biden administration in shaping policy towards China, as White House Indo-Pacific Coordinator and Assistant Secretary of Defense for Indo-Pacific Security Affairs respectively.

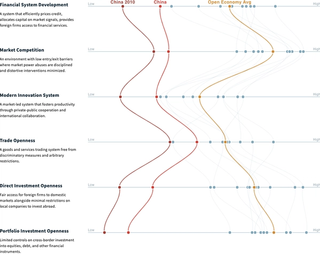

A consideration of some of the key metrics of economic openness suggests that China has continued to make progress over the last decade, despite its recent inward turn. However, it still falls short of the benchmarks set by other more open economies, including the United States, as visualised by The Atlantic Council and Rhodium Group in Figure 1.

Figure 1. 2020 Annual economic benchmarks: How does China’s economic system compare to open market economies?

An examination of the record suggests that US policymakers had low expectations for promoting greater top-down political liberalisation or greater respect for human rights through greater economic engagement. Instead, US policymakers expected that “the creation of more diverse socioeconomic interest groups increasingly dependent on benefits from the outside world would lead to more demand from ordinary citizens for more economic freedom, more lifestyle choices and more government responsiveness…Political liberalisation and democratisation were generally not the main criteria engagers used for judging the success of the policy.”9

Political repression has increased under Xi Jinping, not least in Hong Kong and with respect to ethnic minorities, but this counter-intuitively validates the notion that international economic engagement would threaten the CCP’s grip on power. Increased repression is a sign of political insecurity and a lack of legitimacy. Recent ‘rectification’ campaigns targeting domestic firms, entrepreneurs and industries invoke foreign threats as part of their motivation.10 The specific targeting of foreign influence by the CCP and increased elite support for economic decoupling from the United States effectively acknowledges the threat these pose to CCP rule. President Clinton’s National Security Adviser Sandy Berger made this case when he noted that “bringing China into the WTO is not, by itself, a human rights policy for the United States…Because the Communist Party’s ideology has been discredited in China and because it lacks legitimacy that can only come from democratic choice, it seeks to maintain its grip by suppressing other voices. Change will come only through a combination of internal pressures for change and external validation.”11

China’s WTO accession only served to formalise and make permanent access to US markets that China was already enjoying as far back as the 1980s due to the annual renewal of most favoured nation (MFN) status by Congress.

The argument that bringing China into the WTO was a strategic error on the part of the United States also ignores several relevant counter-factuals. As we shall see in the next section, China’s WTO accession only served to formalise and make permanent access to US markets that China was already enjoying as far back as the 1980s due to the annual renewal of most favoured nation (MFN) status by Congress. There is mixed evidence on the extent to which making China’s MFN status permanent boosted US-China trade by removing uncertainty. Ironically, the annual threat to remove MFN status probably boosted Chinese exports to the United States by bringing forward demand ahead of its possible removal.

It should be recalled that China’s main interest in WTO membership was as a driver of domestic economic reform as much as consolidating the access it already enjoyed to world markets. The main effect of denying China WTO membership would have been to further slow its domestic liberalisation efforts, to the detriment of US exports and investment in China. Denying China WTO membership may well have retarded its economic growth, but this would have come at a cost to US and world economies. It would have undercut broader US efforts to promote regional trade and economic integration and could have also adversely impacted US-China cooperation in a range of other areas ranging from counterterrorism to climate change. China’s economic isolation and impoverishment in the 1950s and 1960s still presented the United States with significant security challenges but without the upside of China’s greater economic openness and participation in the world economy.

Putting the “China Shock” in perspective

Before considering the “China shock” literature specifically, it is worth considering the welfare gains associated with GATT-WTO membership relative to a non-membership counterfactual. Felbermayr et al estimate these effects for 218 countries for the period 1980 to 2016.12 The results are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1. Welfare and trade effects of GATT-WTO membership

|

|

Welfare (%) |

Exports (%) |

|

United States |

1.45 |

20.02 |

|

China |

0.65 |

17.99 |

|

Australia |

1.40 |

15.35 |

|

Average of 218 countries |

4.37 |

14 |

The United States is shown to be a greater beneficiary of GATT-WTO membership relative to China in terms of growth in both manufacturing output and exports. In particular, US manufacturing exports would be 20 per cent lower in the absence of WTO membership. Australia is also shown to be a significant beneficiary of WTO membership.

In a widely discussed paper published in 2013, Autor, Dorn and Hanson (ADH)13 found that regions in the United States more exposed to import competition from China between 1990 and 2007 experienced significantly larger reductions in manufacturing employment, increases in unemployment and non-participation in the labour force, decreases in wages in the non-manufacturing sector, increases in government transfer receipts, and reductions in household income. According to the authors, import competition explained up to one-quarter of the contemporaneous aggregate decline in US manufacturing employment. They did not find significant impacts of trade shocks on changes in regional non-manufacturing employment, working-age populations, or manufacturing wages.

A subsequent paper found import growth from China between 1999 and 2011 led to a loss of employment of 2.4 million workers.14 In related work, Autor and his co-authors linked increased trade exposure to increased political polarisation,15 as well as declines in marriage and fertility16 in the United States. Pierce and Schott similarly linked the decline in US manufacturing employment after 2000 to the United States grant of permanent normal trade relations (PNTR) with China effective from its WTO accession.17 The findings of this literature became known as the “China shock.”

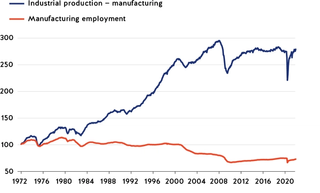

These estimated negative effects of the “China shock” can be placed in perspective by considering US manufacturing output and employment since the early 1970s (Figure 2).

Figure 2. US industrial production — Manufacturing and manufacturing employment (January 1972=100)

Following China’s accession to the WTO, US manufacturing output continued to increase until the onset of the Great Recession in 2007 and has remained close to these record levels since, having already recovered from the 2020 pandemic downturn. By contrast, manufacturing employment has been in decline since the late 1970s, significantly pre-dating China’s WTO accession. The dramatic difference in the trajectories of the two series reflects the growth in manufacturing output per worker or productivity growth in the manufacturing sector, a positive development in both US and world economies.

The “China shock” literature has been the subject of a number of criticisms and rebuttals focused on methodological and other issues. The website chinashock.info conveniently aggregates much of this literature. The two million manufacturing jobs lost over about 15 years is widely considered an upper bound of estimates flowing from this literature. These losses need to be considered in the context of a US labour market characterised by around 60 million job separations every year.18

A major substantive criticism of the “China shock” literature is that it represents only a partial accounting of the net economic benefits flowing from the expansion of US-China trade. Trade with China conferred substantial economic benefits for US consumers, workers and firms. The major empirical findings highlighting offsetting benefits to the labour market dislocations found in the “China shock” literature are summarised on the next page (Box 1). This literature emphasises substantial reductions in US consumer and producer prices, pointing to gains in US consumer and producer welfare along with greater efficiencies due to increased import competition; net gains in aggregate US welfare; and offsetting gains from growth in US exports (Box 1).

Box 1: Offsetting US economic gains from the “China shock”

Price and competition effects

- Amiti et al found that China’s WTO entry reduced the price index for the median US manufacturing industry by eight per cent between 2000 and 2006, over which period Chinese imports to the United States grew 290 per cent by value. Importantly, the largest contribution to the reduction in the effective price came from the lowering of Chinese tariffs on its inputs from which the United States then benefited via cheaper Chinese imports.19

- Similarly, Jaravel and Sager, using a similar empirical strategy to the “China shock” literature, found that increased Chinese import penetration generated benefits to US consumers through lower prices equal to US$101,250 per lost manufacturing job, or a cumulative 1.97 per cent fall in the aggregate US Consumer Price Index between 2000 and 2007.20 The “China shock” is thus shown to have pro-competitive effects that increased consumer welfare.

- Bai and Stumpner found that Chinese imports led to a 0.19 percentage point annual reduction in the price index for US consumer tradeables from 2004 to 2015.21

Aggregate welfare effects

- Using a general equilibrium model, Caliendo et al found increased trade with China accounted for a reduction of about 0.55 million US manufacturing jobs (smaller than ADH), only about 16 per cent of the observed decline in manufacturing employment from 2000 to 2007, but aggregate US welfare still gained by 0.2 per cent.22

- Galle et al found the “China shock” increased average welfare, but some groups experienced losses as high as five times the average gain and these losses were also geographically concentrated.23

Other employment and real wage effects

- Feenstra and Sasahara found that the expansion in US merchandise exports relative to imports from China over 1995–2011 created net demand for about 1.7 million jobs.24

- Feenstra et al found job gains due to US export expansion largely offset job losses due to Chinese import competition, resulting in a net gain of 379,000 jobs over 1991–2011.25

- Xu et al also found the effect on employment of the “China shock” is overstated by failing to account for the effects of the housing cycle, which reduces the independent employment effect of the “China shock” by 20-30 per cent.26

- Wang et al found that China trade boosted employment and real wages downstream from manufacturing and these gains more than offset upstream losses from direct import competition.27

A number of observations can be made based on this short summary of the extensive literature on the topic. The number of job losses attributable to the “China shock” is contested, with a wide range of estimates, but with strong evidence of net gains in overall employment when the broader effects of trade expansion are considered. The literature is consistent, however, in highlighting the highly varied regional and industry impacts of the “China shock.” The geographically concentrated effect of the shock to manufacturing employment gave it greater political salience than the more diffuse benefits to US consumers, other industries and exports, which, in turn, helps account for its role in contributing to political polarisation. Some industries and regions adapted more successfully than others. If anything, the “China shock” raises questions about the domestic US institutions and policy settings that might have slowed the adjustment to the shock. The “China shock” literature then becomes an issue, not of predatory Chinese trade and industrial policy, but of the failure of US politics and public policy to better facilitate adjustment to the shock, particularly at the local and regional level.

How important was WTO accession to the “China shock”?

The decision by Congress to grant China permanent normal trade relations in 1999, taking effect with China’s accession to the WTO in 2001, merely made permanent China’s most favoured nation status granted annually by Congress since 1980. In the absence of MFN status, China would have been subject to the Smoot-Hawley Tariff schedule from 1930. WTO accession did not grant China access to US markets it did not already enjoy, although it did eliminate the uncertainty that accompanied the annual renewal of MFN status. There is mixed evidence on the effect of the removal of this uncertainty. According to one estimate, reduced uncertainty accounted for one-third of China’s export growth to the United States in the period 2000-2005 and lowered US prices and increased consumers’ income by the equivalent of a 13-percentage-point permanent tariff decrease.28 Reducing policy uncertainty was an intended outcome of US policy, which enjoyed bipartisan political support (237 to 197 votes in the US House of Representatives, although with a majority of Democrats opposed). As already noted, reductions in Chinese tariffs on its own inputs contributed to much of the growth in Chinese exports.29

Support for a rules-based multilateral trading system was a long-standing objective of US foreign policy dating back to the formation of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade in the late 1940s, even though US support for a standing institution to give effect to that order was often equivocal.

It is worth considering counter-factuals in which China was denied MFN status. Denying China WTO membership would have substantially weakened the role and effectiveness of the WTO, not least in disciplining China’s economic policies and reducing its trade barriers. Support for a rules-based multilateral trading system was a long-standing objective of US foreign policy dating back to the formation of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in the late 1940s, even though US support for a standing institution to give effect to that order was often equivocal.30

Denying China MFN status would have denied the United States some of the net economic gains associated with the China shock identified in the previous section. However, another likely outcome is that other countries would have expanded their trade with the United States instead of China. Much of the growth in China’s share of US imports was reflected in a declining import share from other jurisdictions. To that extent, the “China shock” was not specific to China, but rather a reflection of broader shifts in the world economy, in particular, the globalisation of manufacturing, which would have occurred even if China remained outside the multilateral trading system. Eriksson shows how the “China shock” simply accelerated existing long-term trends in US industry.31

Does the WTO discipline China’s behaviour?

China’s backsliding on domestic reform and reversion to a state-led development model, starting under Hu Jintao in 2003 and continued under Xi Jinping, has amplified long-standing concerns about China’s trade and industry policy, its role in the world economy and whether the WTO can effectively discipline its domestic and international economic policies, including its use of economic statecraft and coercion.

Under the Trump administration, the US repudiated the WTO as an instrument of economic diplomacy. Instead, it resorted to unilateral tariffs in an attempt to change China’s behaviour, effectively revoking China’s MFN status, prompting retaliatory tariffs that eventually covered the bulk of US-China bilateral goods trade, reversing some of the economic gains from expanded bilateral trade highlighted previously in this report and destabilising the global economy. These tariffs remain in place under the Biden administration, even though President Biden is notionally committed to multilateralism. The Biden administration has also followed the Obama and Trump administrations in continuing to block new appointments to the WTO’s Appellate Body, without specifying what it would take for the United States to change its position on new appointments.

The 8th review of China’s trade policy by the WTO in October 2021 saw 50 delegations line-up to criticise China’s state-led development model, inadequate adherence to WTO rules, as well as its use of coercive trade measures as part of its diplomacy.32 Much of the impetus for reform of the WTO represents an attempt to bring greater discipline to bear on China, particularly in relation to state subsidies, forced technology transfer and digital trade. The criticisms of China demonstrate that the WTO remains a forum to address China’s trade practices, subsidies and other issues, but these criticisms carry less weight to the extent that the United States and other countries also fail to uphold the rules and norms of the multilateral trading system.

Despite its extensive trade and industrial policy abuses, China has a track record of compliance with rulings in WTO disputes.33 WTO rulings have also played a role in disciplining China’s use of economic statecraft, most notably when it lost a WTO case brought by the United States, the European Union and Japan in relation to China’s export controls on rare earths in 2014. Many of the complaints about China’s trade and other practices are actionable in terms of existing WTO rules, but these rules and dispute settlement mechanisms have been under-utilised by the United States and other countries.34 For all the complaints about forced technology transfer, other WTO members, including the United States, have yet to initiate a WTO dispute with China on this issue. China was given considerable forbearance in the early years of its WTO membership, with some justification, but this forbearance was extended for too long. To the extent that there are gaps in existing WTO rules and processes, these gaps are not specific to China, even if China is the main exploiter of these gaps.

To the extent that there are gaps in existing World Trade Organization rules and processes, these gaps are not specific to China, even if China is the main exploiter of these gaps.

China also has legitimate grievances in relation to US and even Australian trade policy. The United States and Australia continue to use non-market methodologies in the calculation of anti-dumping duties, continuing to treat China as a non-market economy for the application of specific duties. US Section 301 tariffs on China, apart from being economically harmful to US and bilateral trade, also undermine the principles underpinning the WTO dispute settlement understanding, which sought to discipline the unilateral use of tariffs.

The Trump administration’s use of tariffs and sanctions to address China’s economic policies had the effect of amplifying Chinese concerns about the risks of economic interdependence with the United States. The US debate over decoupling from China has seen a parallel conversation in Beijing. China has long seen itself engaged in balancing the risks of greater economic openness and interdependence with those of political stability.35 President Xi’s elevation of national security as the overarching consideration for CCP policy has encouraged the pursuit of greater economic self-sufficiency, exemplified by the Made in China 2025 initiative and economic diversification away from the United States. President Trump’s actions validated this shift in perspective on the part of China’s elites. US sanctions against Chinese tech firms and technology containment strategy have “inadvertently done more than any party directive to incentivise private investment in China’s domestic technology ecosystem.”36 These mutually reinforcing actions by the US and China risk further unravelling the multilateral trading system and the economic benefits associated with China’s increased integration with the world economy.

“China shock” or “Deglobalisation shock”?

China’s accession to the WTO in 2001 was soon followed by a peak in globalisation before the global financial crisis of 2008. The crisis was a major deglobalisation shock from which the world economy had not fully recovered at the onset of the pandemic deglobalisation shock in 2020. Deglobalisation refers to a reversal of international economic integration. Even without these shocks, the 20 years since 2001 is characterised by increasing US disengagement from the world economy. As Posen argues, “the US government has not been pursuing openness and integration over the last two decades. On the contrary, it has increasingly insulated the economy from foreign competition, while the rest of the world has continued to open up and integrate.”37

The United States’ disengagement from the world economy is evident across a number of metrics, including its trade-to-GDP ratio, foreign investment, immigration and a lack of major new trade agreements, most notably, the failure to join the Trans-Pacific Partnership in 2017. I reviewed many of these metrics in an earlier USSC report, An open door: How globalised are the Australian and US economies?.38 In another report, Globalisation and labour productivity in the OECD: What are the implications for post-pandemic recovery?, I demonstrate a relationship between slowing globalisation or ‘slowbalisation’ and lower productivity growth for the OECD economies.

This evidence dispels the narrative of the “China shock” — that American workers have been sacrificed on the altar of increased globalisation, spurring the recent rise of populist politics. For one, the timing does not fit. Globalisation wrought its biggest changes in the 1980s and 1990s and peaked around a decade before the rise of populist politics in the United States in 2016 after much of the adjustment to the globalisation of manufacturing had already occurred. Instead, it is just as likely that it is the loss of economic dynamism associated with deglobalisation and decreased US economic engagement with the rest of the world that has given rise to popular discontent. As Posen argues, “even as the United States stepped back from global commerce, anger and extremism have mounted…It is the self-deluding withdrawal from the international economy over the last 20 years that has failed American workers, not globalisation itself.”39

These trends in globalisation can be illustrated with the KOF Economic Globalisation Index (Figure 3).

Figure 3. KOF Economic Globalisation Index

On this measure, economic globalisation in both the United States and China peaked in 2007, although decelerated in the United States from around 2000. The United States is the 59th most globalised economy, whereas China ranks 146th. Despite a generally rising trend from 1980 to 2007, neither economy has ever been at the forefront of globalisation compared to other economies which are relatively more open. Economic globalisation in the United States has stagnated, whereas China has seen an outright decline on this measure, underperforming the rest of the world in terms of global economic integration, notwithstanding the progress shown in Figure 1 in opening up along some dimensions. Barry Naughton notes that China’s re-embrace of indigenous innovation began in 2005 and these industrial policies were largely in place by 2008-2010.40 The slowdown in China’s economic integration and productivity growth was partly externally imposed, a reflection of spillovers and the hangover from the financial crisis, but it also reflects the inward turn under Xi Jinping. Whereas in the United States, ‘slow-globalisation’ has been associated with the rise of populist politics, in China, it has been associated with increased political repression and party control. The CCP has long depended on its ability to deliver rising living standards for its legitimacy. Deglobalisation is a threat to the dynamism of the Chinese economy.

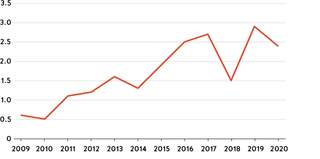

US-China trade frictions are only a subset of much broader trade frictions that have emerged since the financial crisis. Simon Evenett’s Global Trade Alert (GTA) database has documented the growth in discriminatory versus liberalising interventions among G20 economies and the share of G20 members’ exports at risk from these measures.41 The growth in discriminatory measures among G20 economies more broadly has been far more significant than the US-China trade war in terms of the share of world goods trade affected. This has occurred, most notably, through subsidies to import-competing firms and exporters, covering 82 per cent of Chinese exports and 83 per cent of US exports. Accordingly, both the United States and China are affected by rising global protectionism, in addition to their own bilateral trade frictions. Comparing measures that discriminate against foreign commercial interests, the ratio of Chinese measures directed against the United States versus US measures directed against China is on a rising trend (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Ratio of China to United States harmful measures

China has introduced as many as three times as many harmful measures as the United States in recent years, mostly in the form of tariffs and subsidies.43 President Trump’s trade war temporarily interrupted that rising trend by increasing the number of US measures against China, although these also prompted Chinese retaliation.

According to the GTA database, some 62 per cent of global goods trade in 2019 was on products and trade routes where subsidised US, Chinese and EU firms compete. Excluding China from this measure, global goods exposure to subsidies from the United States and the European Union was still 28.1 per cent. China and the European Union together account for 57 per cent of this exposure. As Evenett and Fritz note, “claims that extensive resort to subsidies is found only in state-dominated economic development models should be discounted. Resort to extensive subsidisation is also a common feature of policy in more market-based systems of economic governance.”44 This explains Chinese irritation at being singled out over subsidies. Given that the United States is a lesser offender relative to China and the European Union, it should have a particular interest in the issue of subsidies being addressed through the WTO.

The use of industrial subsidies is likely to grow, partly as a result of increased geoeconomic competition and the policy responses to pandemic shortages. For example, the Japanese government is expected to subsidise up to half the cost of new semiconductor foundries,45 while the US government is also subsidising local semiconductor manufacturing.46 China’s industrial subsidies have increased by a factor of 12 in the last decade to record levels, with semiconductor makers a major beneficiary as part of China’s effort to meet 70 per cent of its chip needs through local production.47 These subsidies and the market response to recent shortages are already expected to lead to excess capacity and over-supply in semiconductors in the second half of 2022 and 2023.48

The growing use of subsidies and other discriminatory trade measures since 2008 on part of China, the United States and the European Union suggests the challenges these measures pose for the multilateral trading system are not specific to China but are more broad-based. Evenett highlights the “wide-ranging breakdown in respect for the National Treatment Principle from the onset of the global financial crisis.”49 The widely hailed 2009 G20 ‘standstill’ on protection and the role of the multilateral trading system in preventing an outbreak of 1930s-style protectionism in the wake of the financial crisis has been exaggerated. The US-China trade war served to dramatise what were already deep-seated problems with the multilateral trading system in disciplining its members, but this is more a problem of its inconsistent application and under-utilisation than with the fundamental principles of multilateralism or their institutionalisation through the WTO. While the US-China trade war has greater geopolitical salience, the creeping protectionism that undermines the multilateral trading system is of greater economic significance as a driver of deglobalisation.

Where to for the WTO? An agenda for reform

Pessimism about the future of the WTO is endemic to its history. In 1978, the doyen of international economic law, John H. Jackson, wrote, “we are currently undergoing the greatest challenge to the liberal trade system, including GATT, since the formulation of that system in the immediate post World War II period.” Jackson cited “growing scepticism about the economic model of liberal trade” and “growing recognition of the dangers and disadvantages of economic interdependence” as reasons for pessimism.50 As Harold James noted in 2000, the death of the multilateral trading system has been predicted many times in the past and yet the system muddled through.51 While the WTO has not successfully concluded a new round of multilateral trade liberalisation since the Uruguay round, it continues to progress important plurilateral agreements, such as the recent agreement on the domestic regulation of services and the 2013 Trade Facilitation Agreement, while also providing a system of binding dispute resolution, notwithstanding the current impasse over the Appellate Body.

In 2000, James argued the globalisation that reflected the so-called Washington consensus was more robust than earlier multilateral orders because it was built less on treaties and more on “sustained reflection about appropriate policy and the gains to be derived from it.” However, he was writing at the high point of globalisation in the early 2000s. While he anticipated the risks posed by future financial crises such as the one in 2008, he did not anticipate the implications of future US-China strategic competition.

The WTO has the potential to discipline that competition and limit its potential to destabilise and deglobalise the world economy. The WTO also has a potentially important role to play in disciplining trade conflict and protectionism arising from disagreements over climate change mitigation measures under the Paris Agreement. The Paris Agreement is notable for being based on self-determined mitigation contributions, without the benefit of formal or binding rules, reciprocity and enforcement mechanisms that characterise the WTO.52 The WTO provides an important venue for resolving trade disputes arising from climate change mitigation efforts that cannot be addressed through the Paris framework.

While the WTO continues to play a central role in providing a framework of rules for international trade, it needs to be reformed to meet contemporary challenges along the following lines.

Purpose, principles and leadership

The WTO’s principles of reciprocity and non-discrimination are key to its ability to encourage the implementation of efficient trade agreements.53 It is these principles that are being violated through the growth in discriminatory measures such as subsidies highlighted by the GTA database project. It is important to recall that the WTO itself does not set or enforce rules, its members do.54 Andy Stoeckel argues that the “waning of a global leader [i.e., the United States] that is willing to foster a coherent open multilateral system” is one of the main problems confronting the WTO. He suggests “it is the leadership of ideas aspect where the United States could influence the WTO system for the better, if it chooses to do so.” US leadership is both cause and solution to many of the issues confronting the WTO. But to win support in Washington, that leadership needs to be reframed in terms of its contribution to winning a global rule-making competition with China.

US leadership is both cause and solution to many of the issues confronting the WTO. But to win support in Washington, that leadership needs to be reframed in terms of its contribution to winning a global rule-making competition with China.

A fundamental issue for the WTO is the lack of agreement on the goals and purposes of the organisation. Integration of the world economy cannot be assumed to be a shared goal when the world’s two largest economies are seeking to selectively disengage and diversify away from one another. One of the biggest challenges facing the multilateral system is to find ways in which competing models of market- and state-led capitalism can co-exist under a common set of agreed rules.55 Stoeckel suggests that members can nonetheless still agree on the WTO as a framework for promoting economic development and on the principle of non-discrimination as the basis for a rules-based trading system.56

Many of the problems with the WTO have their basis in mission creep and departures from the foundational principle of non-discrimination, as well as the judicialisation of dispute settlement, which has led to US complaints the dispute resolution mechanism has strayed beyond adjudication into lawmaking. Focusing the WTO on its core mission and upholding these principles suggests a number of possible reforms to the WTO that could be championed through both US and Australian leadership as part of a coherent vision for reform.

Addressing subsidies

At the 11th WTO Ministerial Conference in December 2017, the United States, Japan and the European Union began a trilateral process to address China’s use of industrial subsidies and state-owned enterprises,57 a process that was renewed in a joint statement by the three parties on 17 November 2021.58 China has also advanced its own subsidies reform agenda. Given the growing role of subsidies in undermining the multilateral trading system, improving and promoting greater compliance with the WTO Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM) with a view to prohibiting discriminatory industrial policies should be a priority. This should include significant enhancements in notification requirements to improve monitoring of trade policy developments. The GTA database demonstrates that the WTO’s existing notification and monitoring systems are not adequate, allowing the multilateral trading system to be undermined with little effective scrutiny.

Stoeckel suggests that the WTO’s membership follow the Australian model of introducing a transparency body such as the Productivity Commission to assess the economy-wide costs and benefits of trade and industry policy, in particular, anti-dumping measures. The proliferation of anti-dumping measures has been a major source of tension within the system and of US dissatisfaction with the WTO as an adjudicator of trade disputes. The WTO’s Trade Policy Review Mechanism could also follow the Productivity Commission model in its approach to assessing economy-wide costs and benefits.

Multilateralise preferential trade agreements and reform trade preferences

The US and Australian preference for bilateral and regional trade deals outside the WTO has reflected frustration at the lack of progress in multilateral trade liberalisation but has also been a contributing factor in undermining multilateralism. Another of Stoeckel’s proposals is to multilateralise existing and prospective preferential trade agreements (PTAs) so that these agreements support rather than undermine the principles of multilateralism. This would entail the United States and Australia offering their best terms from each PTA to all WTO members on a MFN basis. At the very least, these terms should be offered to WTO members within the US alliance network as a way of expanding and diversifying intra-alliance trade, even if this compromises the principles of multilateralism.

Eliminating preferences, including special and differential treatment for developing economies, would be more consistent with the WTO’s core principles. Australia should follow Canada, the European Union, the United Kingdom and other countries that will terminate China’s general system of preferences (GSP) benefits from 1 December 2021.59

Digital trade

The United States and Australia could also play a leadership role in fostering a WTO-compliant plurilateral digital trade agreement, particularly given the US interest in preventing foreign discrimination against its leading tech firms and the growing dangers presented by digital protectionism, where China is a major offender. Digital commerce is one of the fastest-growing areas of cross-border trade but is still largely outside the scope of existing WTO rules, reflecting their origin in a pre-digital era, while China is aiming to become a ‘cyber great power’ through its ‘digital silk road.’

Appellate body

Finally, the US needs to spell out the conditions under which it would unblock new Appellate Body appointments to provide a basis for negotiations on rebooting the system of binding dispute resolution. China’s participation in the Multiparty Interim Appeal Arbitration Arrangement, designed as a workaround mechanism while the Appellate Body is frozen by the United States, makes China look like a more responsible actor in the multilateral system.

Conclusion

China’s accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001 was an important element of its growing integration into the world economy, as well as its domestic economic reform program dating back to 1978. In terms of access to US markets, accession only served to make permanent access China had enjoyed since the 1980s. While estimates vary as to the importance of the implicit trade barrier represented by uncertainty around whether the US Congress would renew China’s MFN status each year, it is likely that the elimination of this uncertainty in 2001 was economically significant.

The granting of PNTR was part of a broader effort to open up the Chinese economy and engage China economically and politically as a member of the rules-based liberal order. While this effort was broadly successful, and the United States was a net beneficiary economically, there is now a bipartisan view in the United States that economic engagement came at a cost both to the economy and in terms of geopolitical rivalry. The World Trade Organization is increasingly viewed by US policymakers as ineffective, both in promoting trade liberalisation, but also in disciplining China’s trade and industrial policies.

Australian policymakers, by contrast, remain supportive of the multilateral trading system. Prime Minister Scott Morrison has called for a G7-led effort to reform the WTO as a key element of a collective pushback against China’s use of economic statecraft in particular. Australian policymakers face a major challenge in bringing their US counterparts closer to the Australian position.

Effective US leadership of the multilateral trading system would not only promote US foreign policy objectives such as prosecuting its strategic competition with China but would also discipline US domestic economic policy in ways that would better serve its economic interests while also providing a rules-based framework for managing trade frictions arising from climate mitigation under the Paris Agreement.

The “China shock” literature has highlighted the number of US manufacturing jobs lost to import competition from China in previous decades and its broader economic, social and political effects. However, an overall assessment of the economic impact of the “China shock” suggests the expansion of trade has been a net positive for the US economy. The “China shock” was a continuation of long-run trends in the US economy due to the globalisation of manufacturing. Had the United States resisted China’s integration into the global economy, greater import-competition would have almost certainly arisen from other sources, leading to similar outcomes.

President Trump’s trade war and sanctions against China led Chinese elites to equally question the extent of economic interdependence with the United States. President Trump’s ‘America First’ policies and President Biden’s ‘foreign policy for the middle class’ are mirrored in China by Xi’s advocacy of a concept of national security that embraces economic self-sufficiency, aspires to global technological leadership, engages in economic statecraft and seeks to diversify away from economic engagement with the United States. Xi Jinping has revived the Maoist concept of ‘self-reliance,’ explicitly citing the rise of foreign unilateralism and trade protectionism as the motivation. Far from calling out and disciplining China’s behaviour, President Trump’s trade policies, maintained by the Biden administration, have encouraged China to double-down on its state-led development model and strategic industry and trade policy, while potential multilateral solutions and processes have been neglected and under-utilised.

The multilateral trading system has been undermined by creeping protectionism since the financial crisis of 2008 coinciding with a global productivity slowdown that is strongly suggestive of a causal link between the two. Instead of being a champion of globalisation, the United States has increasingly disengaged from the world economy over the last 20 years, beginning with the failure of the WTO ministerial meeting in Seattle in 1999 and culminating most dramatically in its failure to join the centrepiece of the Obama administration’s economic diplomacy, the Trans-Pacific Partnership in 2017. This retreat added impetus to a rolling deglobalisation shock and the associated loss of economic dynamism, more so than the “China shock,” bred populist political impulses in the United States. Globalisation wrought its biggest changes in the 1980s and 1990s, well before the outbreak of populism in 2016.

A key to restoring domestic political support for US leadership of the multilateral trading system is to reframe that leadership in terms of strategic competition with China around the rules and norms of the global economy. Effective US leadership of the multilateral trading system would not only promote US foreign policy objectives such as prosecuting its strategic competition with China but would also discipline US domestic economic policy in ways that would better serve its economic interests while also providing a rules-based framework for managing trade frictions arising from climate mitigation under the Paris Agreement and growth in the digital economy.