Executive summary

- Over the past four years, defence industrial and technology cooperation have become the focus for America’s efforts to modernise key alliances and strategic partnerships in the Indo-Pacific, particularly those with Australia, India, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan.

- Though Washington has previously pursued greater defence industrial integration with these countries in the past, this agenda has assumed a new urgency in the wake of a number of sudden shocks and longer-standing challenges to the US defence industrial base.

- Near-term challenges emanating from the COVID-19 pandemic, Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine, and renewed operational commitments in the Red Sea and Mediterranean since October 2023 have called into question Washington’s ability to meet both its own and its allies’ material defence needs.

- These shocks are compounded by legacy maintenance and production shortfalls and China’s growing ability to contest US military logistics in Asia, posing serious challenges to America’s strategic position in the Indo-Pacific.

- To address these challenges, Washington and its regional allies and partners seek to progress cooperation along three primary vectors: maintenance, repair and overhaul; co-production and defence supply chains; and defence technology development. Importantly, this has occurred not only at the bilateral alliance and partnership level but also at the minilateral level through initiatives like AUKUS, the Australia-Japan-US trilateral, and new mechanisms like the Regional Sustainment Framework and Partnership for Indo-Pacific Industrial Resilience.

The election of the second Trump administration and its willingness to pursue ambitious reforms to defence industrial policy and regulation provides an opportunity to capitalise on the strong foundation for defence industrial and technology integration with Indo-Pacific allies and partners laid to date.

- However, the United States and its allies and partners have also encountered a number of common obstacles to advancing this defence integration agenda, both within and between their respective systems. These include lingering barriers to defence trade and technology sharing; sluggish acquisition processes and insufficient innovation incentives; the over-classification of information and shallow supply chain visibility; the weaknesses and burdens of industrial security standards; and political tensions between onshoring and friend-shoring defence production.

- Notwithstanding these challenges, the election of the second Donald Trump administration and its willingness to pursue ambitious reforms to defence industrial policy and regulation provides an opportunity to capitalise on the strong foundation for defence industrial and technology integration with Indo-Pacific allies and partners laid to date. Broadly speaking, these efforts ought to focus on: institutionalising new information-sharing practices; deepening industry engagement; exploring collective industrial mapping and crisis simulation activities; harmonising defence industrial security measures; and reforming defence acquisition and trade practices to quickly deliver disruptive capabilities. a strong foundation for a defence industrial integration agenda with Indo-Pacific allies and partners to succeed.

Introduction

In December 2024, then-United States National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan delivered an address to the Center for Strategic and International Studies, entitled “Fortifying the U.S. Defense Industrial Base.”1 That Sullivan chose to give such a high-profile address on such a technical topic with approximately a month remaining in office, and after a highly eventful four years, was no coincidence. Indeed, it was reflective of America’s growing preoccupation with revitalising the US national defence industrial base (DIB), a pursuit which Sullivan cast as “a deeply strategic topic… for the future of American statecraft.”2

In large part, Sullivan used his address to reflect on the administration’s efforts to “modernize, invigorate and expand” the DIB through three “big pushes” — boosting munitions and shipbuilding production capacity, bringing more commercial technologies into the defence realm, and building “an integrated defense industrial base” with global allies and partners.3 That alliances and partnerships warranted their own discussion was unsurprising. Indeed, the 2022 National Defense Strategy (NDS) identified a rejuvenated US defence industrial base, access to high technology, and America’s network of capable allies and partners as “enduring advantages,”4 essential to meeting US objectives across the full spectrum of statecraft. Importantly, the Biden team saw these advantages not as mutually exclusive but as interdependent factors essential to American strategic success.

The Biden administration’s successes and challenges

The administration’s efforts to modernise and network America’s Indo-Pacific alliances and partnerships — particularly those with Australia, India, Japan and the Republic of Korea (ROK) — epitomised that view.5 This included expanded bilateral collaboration with all four countries on federated maintenance, production and sustainment initiatives for aircraft, munitions, warships and unmanned systems; the creation of several signature industrial capacity-building and technology sharing initiatives, most notably the Australia-United Kingdom-United States (AUKUS) partnership and the India-US Defense Acceleration Ecosystem (INDUS-X); and the creation of new defence industrial-focussed minilateral forums like the Regional Sustainment Framework and Partnership for Indo-Pacific Industrial Resilience. For the most part, these initiatives have been intended to address China’s growing regional military power, identified by the 2022 NDS as the outright “pacing challenge” for the US Department of Defense and, by extension, defence industrial integration and technology collaboration with allies and partners.6

These efforts to prioritise China and the Indo-Pacific were both driven and tested by a range of domestic and global challenges, which, collectively, called into question America’s industrial capacity to meet both its own national priorities and its global security commitments. The lingering impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the American economy and workforce extended to the national DIB. Sustained material support for Ukraine in the face of Russia’s February 2022 invasion exposed shortcomings in America’s capacity to backfill depleted stockpiles and to produce even basic defence items at scale. A concurrent surge in military aid for Israel and a surge in protracted air and naval operations in the Mediterranean and the Red Sea — only years after the end of the US mission in Afghanistan — not only depleted already low stocks of strike weapons and air defences, but compounded with long-standing maintenance and sustainment shortfalls which had already degraded US military readiness in Asia. On top of industrial issues, the Indo-Pacific’s vast air and maritime geography and China’s rapid military modernisation have made for an increasingly contested military logistics environment, calling into question America’s capacity to credibly supply and sustain its own forces, let alone those of its allies, in a range of plausible pre-crisis or conflict scenarios.7

The 2024 National Defense Industrial Strategy

It was these compounding headaches that prompted the publication of the first-ever US National Defense Industrial Strategy (NDIS) in January 2024, a document intended to provide a roadmap towards “a more robust, resilient, and dynamic modernized defense industrial ecosystem.”8 Though much of the document focusses on domestic reform and revitalisation, it also retains a distinct focus on the Indo-Pacific as America’s primary theatre of interest and on allies and partners as essential inputs to American strategy, noting that realising “a modernized defense industrial ecosystem that is fully aligned with the NDS” would be contingent on deeper integration with those countries.9 Indeed, the NDIS frames such cooperation as central to three of the four long-term strategic priorities — building resilient supply chains, developing more flexible acquisition systems, and bolstering economic deterrence — while it is closely related to achieving the fourth — enhancing workforce readiness (see Table 1). Encouragingly, progress has been made on all six of the specific implementation initiatives outlined in the June 2024 NDIS Implementation Plan — including shoring up the US submarine industrial base, expanding missile production for “Indo-Pacific Deterrence,” and correcting long-standing maintenance and sustainment imbalances — hinges on allied and partner contributions.10

Much work remains to be done if the United States, under a second Donald Trump administration, is to fully capitalise on the comparative advantages that US Indo-Pacific allies and partners can bring to bear in support of shared regional objectives.

Yet much work remains to be done if the United States, under a second Donald Trump administration, is to fully capitalise on the comparative advantages that US Indo-Pacific allies and partners can bring to bear in support of shared regional objectives. For America and its allies and partners alike, realising the promise of greater defence industrial integration in the Indo-Pacific will require addressing several cross-cutting challenges. These include: (but not limited to): reforming outdated defence trade controls; revising information classification standards across different military services and departments; removing barriers to private sector participation in US and allied defence markets; reforming and harmonising acquisition procedures, including equipment specification standards and tender processes; right-sizing cybersecurity requirements; enhancing collective defence supply chain domain awareness; and insulating critical defence industrial and technology collaboration from excessive protectionism.

Over to you, Trump 2.0

As Sullivan himself noted at CSIS, while the Biden administration had “made progress over the last four years… frankly, we need progress over the next 40.”11 In the first instance, it will fall to the second Donald Trump administration to carry this agenda forward. At the time of writing, the precise contours of American defence strategy under Trump 2.0 remain unclear, with robust debates underway within and between the new administration, Congress and the broader policy community over how best to right-size US global strategy and to radically reform the American defence establishment that has proven slow to adapt to a new era.12 At the same time, the various camps within these debates all agree on the need to better position America for military competition with China and, by extension, on the need to continue to revitalise the US defence industrial base in the pursuit of what President Trump and his national security team have broadly referred to as “peace through strength.”13 Whichever way it chooses to implement that concept in practice, and to what extent the maxim “production is deterrence” informs that concept, the new administration will ultimately need to consider how best to leverage defence industrial integration and technology collaboration with Indo-Pacific allies and partners to meet those objectives.

In that spirit, this report seeks to assess the recent history of US-allied defence industrial integration in Asia to offer lessons for the near future. It begins with a discussion of the main drivers of that agenda, unpacking the challenges posed to America’s strategic position in Asia by the effects of COVID-19, major conflicts in Europe and the Middle East, legacy maintenance and sustainment challenges, and the contested logistics environment in the Indo-Pacific. It then examines how the United States has sought to advance bilateral and minilateral defence industrial and technology collaboration with Australia, India, Japan, South Korea and others over the last four years as part of wider efforts to modernise its own national defence industrial case, focussing on developments relating to: maintenance, repair and overhaul (MRO); co-production and supply chains; and defence technology collaboration. The report identifies several common challenges that have presented themselves across these various partnerships, before concluding with a series of recommendations for policymakers in all five capitals to consider as the Trump administration embarks upon its own efforts to reinvigorate the US DIB, bolster deterrence in the Indo-Pacific, and advance defence industrial and technology cooperation with allies and partners.

Table 1. Role of allies and partners in the four long-term priorities of the United States’ 2023 National Defense Industrial Strategy

1. Drivers of the industrial integration agenda

To be sure, many of the challenges afflicting the US DIB are not necessarily new, predating both the Biden and Trump administrations, respectively, by many years. Since the end of the Cold War, scholars and US Government departments alike have long warned of a steady atrophying of US national defence industrial capacity, including the consolidation of defence production capacity in the 1990s and subsequent creation of bottlenecks for key components, the steady deterioration of force readiness, procedural and regulatory impediments to innovation and procurement, political ceilings and legal constraints of defence spending, and so on. Even as defence policy experts took greater interest in these challenges amid China’s own growing industrial capacity, military power and technological sophistication, a relatively benign global strategic environment (notwithstanding protracted US and coalition military campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan) meant that many of these issues were left unaddressed or unexposed while those that did receive attention experienced only incremental changes or improvements.

However, beginning in early 2020, a series of major shocks brought these challenges to the forefront of American — and allied — defence policy debates, exaggerating preexisting vulnerabilities and/or uncovering new weaknesses or challenges. The need to respond to these challenges that has driven Washington’s recent efforts to advance defence industrial and technology cooperation with key allies in the Indo-Pacific. These shocks included the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on US supply chains and workforce, and the industrial pressures of unplanned and protracted military support for partners confronting aggression in Europe and the Middle East. These challenges compounded with longer-standing issues relating to legacy air and naval readiness and sustainment backlogs, and the increasingly contested nature of the military logistics environment in the Indo-Pacific theatre as China’s air, naval and strike capabilities have grown in size and sophistication, pressuring America’s ability to sustain its forces and those of its partners in the event of hostilities.

a. COVID-19

Firstly, the COVID-19 global pandemic underscored the brittleness of important defence supply chains and exacerbated existing readiness challenges, including maintenance, repair and overhaul (MRO), driven in large part by the resultant strain on America’s workforce.14

Supply chains

Most glaringly, the pandemic laid bare the fragility of global supply chains, uncovering key gaps in the US industrial base and an overdependence on foreign manufacturing for key inputs.15 An official action plan released in February 2022 in response to President Biden’s Executive Order 14017, entitled “Securing Defense-Critical Supply Chains,” sought to identify gaps in supply chains relevant to microelectronics, castings and forgings, missiles and munitions, energy storage and batteries, and strategic and critical materials. The document outlined plans to secure these supply chains, including through actions like “build(ing) domestic production capacity.”16 For US defence companies, these pandemic-driven vulnerabilities have serious consequences on the availability of materials, subcomponents and other goods.17 Lockheed Martin, for example, experienced a reduced capacity to build and sell F-35 fighter jets to customers, including the US Department of Defense.18

Following the pandemic, the administration and Congress enacted numerous initiatives designed to improve supply chain transparency and resilience; strengthen workforce development and lift support for small businesses in the defence industrial base.19 This included the pursuit of legislative reforms such as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, which enabled domestic investments in supply chains for critical dual-use technologies of importance to national security.20 Meanwhile, the House Armed Services Committee established a critical supply chain task force to review defence industrial supply chains and “identify and analyse threats and vulnerabilities.”21 Among other recommendations, the task force ultimately suggested the DoD “treat supply chain security as a defence strategic priority.”22 This call was heeded with the release of the Biden administration’s National Defense Industrial Strategy, which identified “supply chain resilience” as the first of four long-term priorities for the US defence industrial base.23

Workforce

The pandemic had equally devastating effects on America’s defence industrial workforce, forcing changes to the way people work and in doing so prompting many to consider new career paths with different working conditions or early retirement.24 These challenges were compounded by a pre-existing “aging” out of much of the DIB workforce, with a 2023 McKinsey and Company study noting one-third of US defence industry employees are age 55 or older.25 The net effect of these shifts was that naval shipyards and other critical defence industrial workplaces could not operate at capacity during and after the pandemic, producing new or extended delays to important capability production and modernisation initiatives.26 Delays to the construction of Virginia-class submarines is one notable example. Company spokespeople from Newport News Shipbuilding have publicly stated that COVID-related workforce challenges and subsequent staff shortages up and down the Virginia-class supply chain prompted the Navy and its two major manufacturers for the boats to redraw the schedule for production of Block V.27 After the pandemic, Navy officials have attributed ongoing workforce shortages in the defence industrial base to the declining wage gap between blue-collar jobs in hospitality and companies such as Amazon.28

COVID-related workforce shortfalls also had flow-on effects for US allies and partners. For example, workforce shortages produced notable delays in the production, maintenance and sustainment of US Virginia Class submarines — the model that Australia plans to purchase from the United States under Phase II of AUKUS Pillar I.29 Indeed, a June 2023 US Government Accountability Office report said that workforce shortages amplified by the pandemic had produced an additional two years of delay to the Block V Virginia class.30 To address these challenges, the Biden administration introduced a range of talent retention and recruitment measures, including introducing a US Navy Talent Pipeline Program and supporting increases in remuneration and benefits for shipyard workers,31 though these initiatives will take time to realise their full effects.

b. Global security commitments

On top of the pandemic, simultaneous conflicts in Europe and the Middle East put additional pressure on an already strained DIB. As these conflicts have dragged on, they have stretched America’s capacity to simultaneously resource allies and partners on the frontlines of conflict in secondary theatres while simultaneously maintaining the readiness levels and weapons stockpiles required to underwrite US deterrence strategy in its primary theatre of interest, the Indo-Pacific.

Ukraine and Europe

Whichever way one looks at it, Washington’s consistent material support for Ukraine in the face of Russia’s invasion exposed acute supply bottlenecks for key military systems and the inadequacy of “just in time” delivery models to meet wartime demands, particularly with respect to munitions. Between February 2022 and January 2025, Washington provided over US$66.5 billion in military aid, including thousands of rounds for air defences, High Mobility Artillery Rocket Systems (HIMARS), Javelin anti-armour systems, and Stinger anti-air systems; over three million rounds of 155mm artillery ammunition and over one million 105mm artillery rounds; and large numbers of other in-demand systems.32 In order to meet the urgency of these requirements and to buy time for industry to surge its capacity to meet sudden requirements, the Biden administration primarily utilised Presidential Drawdown Authorities to supply Ukraine with materials directly from US war stocks. Though industry was able to improve its production capacity for certain capabilities, over time these efforts reduced US inventories for key munitions to close to minimum war planning and training requirements.33 This generated considerable debate over whether protracted support for Ukraine would undermine US or allied warfighting potential in the Indo-Pacific, including amongst figures likely to join the second Trump administration.

This generated considerable debate over whether protracted support for Ukraine would undermine US or allied warfighting potential in the Indo-Pacific, including amongst figures likely to join the second Trump administration.

As the range and sophistication of US weapons transfers to Ukraine has expanded, so too has the number of defence industrial challenges increased. This has been especially evident with respect to munitions. In January 2023, experts projected that it would take more than five years to upgrade production capacity for 155mm artillery shells, Javelin anti-tank weapons and Stinger anti-air missiles — all essential to Ukraine’s defensive efforts — at levels required to replenish US reserves based on prevailing consumption rates.34 While the US had previously maintained a more robust production capacity for these capabilities, this had atrophied following the end of the Cold War and amid in US operations in the Middle East. For example, US Javelin production had contracted by two-thirds between 2009 in 2013 in response to a pause in US military campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan, while HIMARS production had been paused altogether between 2013 and 2017,35 with neither capability enjoying a significant expansion of manufacturing capacity to meet new demands. While the production of HIMARS launchers was on track increase from 60 to 96 per year by the end of 2024,36 demand for these systems globally — not just in Ukraine — has increased significantly in recent years (see Table 2), raising questions over America’s capacity to supply its allies with the weapons they require to contribute to upholding deterrence.

Table 2. Publicly announced HIMARS sales/transfers approved since February 2022

The Ukraine conflict also highlights the perils of industrial base consolidation and the creation of acute supply bottlenecks for critical components. This rings true across both the organic industrial base — the portion of US industrial capacity owned and operated by the government — and private industry, and particularly for precision-guided munitions. More so than complete capabilities themselves, it is shortages of such components that have had a direct bearing on US resources and planning in other global theatres. Manufacturing and supply shortages for rocket motors are a case in point, with only two certified suppliers able to meet production demands for a wide range of defensive and offensive missile systems beyond those employed in Ukraine,37 placing demand for legacy system componentry for capabilities like the Javelin in direct competition with those needed for air and maritime precision guided munitions production.38 This effected not only delivery timelines for completed capabilities but the rate at which other elements of the US DIB could reconstitute. For example, though annual guided multiple launch rocket (GMLR) production increased from 6,000 to 10,000 within the first 12 months of the war year,39 industry predicted that it would take another two years to further double production to 20,000 given intense competition for “machine tools, skilled labor, and parts” between multiple classes of precision-guided munitions.40

In response, Congress and the White House took considerable steps to address these supply crunches. In February 2023, a Pentagon memo indicated that the department was undertaking “munitions industrial base deep dives” targeted specifically at enhancing production capacity for “integrated air defense systems” and “long-range fires.”41 Meanwhile, Congress extended multi-year purchasing authorities, traditionally reserved for major weapons platforms like warships, to precision munitions in the FY23 National Defense Authorization Act, and subsequently granted six of eight multi-year munitions contracting requests in the Pentagon’s FY24 budget,42 including for several with clear application to the air and maritime domain in the Indo-Pacific.43 The US Army has also awarded billions in contracts for 155mm and GMLR production since 2023 to meet Ukrainian and US inventory demands,44 including through outsourcing to allied countries.45

Despite this progress, however, the United States has encountered difficulties in ramping up production to meet Ukraine’s battlefield needs, let alone its own inventory requirements. The Pentagon has enjoyed some notable success in surging production capacity for 155mm artillery shells,46 and is on track to up production from a pre-war level of 25,000 units a month to 100,000 units a month by October 2024.47 Yet even in coalition with other Western producers, this would still fall short of even more conservative estimates of Ukraine’s battlefield requirements, and would constitute only 40% of Russia’s estimated monthly 155mm output.48 Undersecretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment William LaPlante noted in congressional testimony in February 2024 that “the tyranny of lead time” remained a considerable challenge for precision weapons like the Javelin, Stinger, and GMLR, with production timelines remaining at “two to three years” given the complexity of these systems.49 This was a particularly sobering assessment, given that unclassified wargaming had shown that US stockpiles of precision munitions relevant to high-end contingencies in Asia would likely be exhausted in less than a week of fighting.50

Though the Ukraine war has exposed weaknesses within the US defence industrial base, for the Biden and now Trump administration — as well as US allies and partners in Asia — Ukraine has provided sober, albeit useful, lessons about the utility of asymmetric unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) in modern warfare, commonly referred to as drones. Over the course of the conflict, UAVs have become ubiquitous, largely because of their cost-effectiveness and ability to elevate “dumb artillery rounds” into more effective weapons.51 In fact, there is evidence to suggest the fielding of drones en masse supports enhances air defence against Russian missile strikes.52 This dynamic may bear some wisdom for Taiwan and those with an interest in deterring a Chinese attack over the Taiwan Strait. Though it is highly unlikely UAVs would be sufficient on their own to deter a Chinese attack, officials such as Admiral Paparo, Commander of US Indo-Pacific Command, have implied deploying swarms of unmanned systems over the strait would “buy time” for the deployment of traditional assets in the event of a Chinese invasion.53 Other former senior US officials, including Michèle Flournoy, who served as Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, have added that augmenting traditional assets with a mass of “relatively cheap unmanned systems” could compensate for China’s geographic advantage in the Indo-Pacific.54 The promotion of attritable, unmanned systems will likely fall on open ears with the Trump administration and, in particular, Elon Musk, who presides over the new Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE). Musk previously voiced his disdain for traditional systems like the F-35, arguing they have become obsolete with the rise of unmanned systems.55

Israel, the Red Sea and the Middle East

Unanticipated and increasingly protracted military operations in the Middle East have worsened industrial pressures associated with Ukraine. Arguably more so than conflict in Europe, renewed and protracted air and maritime operations in the Middle East have underscored how US global security commitments are putting pressure on its industrial capacity vis-à-vis requirements in Asia. To its credit, the Biden administration had made considerable efforts throughout its first three years in office to minimise America’s military presence across the region, ending so-called “forever wars” to focus on challenges posed by China and Russia.56 Beyond withdrawing all US forces from Afghanistan by August 2021, the Biden team also relocated or withdrew many high-end ballistic missile defence systems, naval, air force and surveillance assets away from the Persian Gulf to “answer military needs elsewhere around the globe,”57 including many of those deployed to the Middle East in the final year of the Trump administration to manage escalation dynamics with Iran. The absence of a major regional conflict before Hamas’s attack on Israel in October 2023 led Jake Sullivan to opine for Foreign Affairs that the administration’s “disciplined approach” and risk reduction measures in the Middle East had strengthened America’s hand to respond to more pressing global priorities.”58

Since then, however, renewed defence commitments in the Middle East have sapped US defence industrial strength and military readiness in three main ways. Firstly, the surge in material assistance for Israel forced the administration to draw on the Pentagon’s own stockpiles of munitions, including those of other regional combatant commands. Indeed, to meet Tel Aviv’s initial requirements for 155mm ammunition, Washington was forced to tap stockpiles nominally reserved for US European Command (albeit based in Israel), known as War Reserve Stocks for Allies-Israel (WRSA-I).59 This meant that tens of thousands of stockpiled shells originally earmarked for delivery to Ukraine were subsequently redirected to Israel ahead of anticipated ground operations in the Gaza Strip.60 The decision to reallocate these munitions came at a time when Ukrainian forces were experiencing acute 155mm shortages in the face of multiple Russian assault vectors, and when 155mm supplies across NATO and other aligned countries were reaching “the bottom of the barrel.”61

Secondly, US forces have expended hundreds of high-end strike and air defence missiles in the defence of Israel and in prosecuting two concurrent air and maritime operations in the Red Sea (Prosperity Guardian, a multinational effort to protect commercial shipping; and Poseidon Archer, a combined US-UK strike mission targeting threats inside Yemen). Between November 2023 and July 2024, for example, the US Navy estimates that the warships in the Dwight D. Eisenhower Carrier Strike Group launched over 800 missiles: 155 standard missiles (US$2-4 million per missile) and 135 Tomahawk land attack missiles (US$2 million per missile), while its aircraft launched at least 60 air-to-air missiles and 420 air-to-surface weapons.62 Many of these weapons have been launched against comparatively low-cost man-portable and unmanned systems, making for a highly unfavourable cost curve as these operations have continued. What’s more, their high expenditure rates also raised concerns among senior US defence figures, including Indo-Pacific Commander Admiral Samuel Paparo and former Assistant Secretary of Defense for Strategy, Plans, and Capabilities Mara Karlin, as to whether the United States could simultaneously meet Israeli and Ukrainian requirements as well as US operational needs in the Indo-Pacific if conflicts in both regions dragged on indefinitely.63

Indeed, expenditure rates for certain munitions, including those relevant to prospective contingencies in Asia, have far exceeded both past and forecast procurement rates.64 For instance, the US Navy expended over 80 Tomahawk land attack missiles in the opening days of its Red Sea Operations alone, amounting to 145% of Tomahawks procured the previous financial.65 This mismatch between procurement and expenditure is not new. For example, the Pentagon procured only 80% of the 125 Tomahawks used in its 2017-2018 strike campaigns against Syrian Government targets in its 2018 and 2019 budgets.66 These high consumption rates come at a time when a growing number of frontline allies in Asia, including Australia and Japan, are seeking to purchase hundreds of Tomahawks of their own,67 raising questions about US capacity to meet both its own and its allies’ needs. Indeed, previous shortages of Hellfire missiles, Joint Direct Attack Munition kits and Small Diameter Bombs during US Air Force campaigns against the Islamic State group in Iraq and Syria in 2016 caused US authorities to turn down allies’ requests to purchase these same capabilities.68

Table 3. United States Standard Missile-3 Interceptor procurement since FY15

Table 4. United States Tomahawk Land Attack Missile procurements over the last decade

Table 5. United States Patriot interceptor procurement over the last decade

Thirdly, US operations in the Mediterranean and Red Seas have produced additional sustainment costs on top of the Pentagon’s already strained operations and maintenance accounts. In resourcing its initial regional surge in October 2023, and in the absence of a final defence budget for 2024, the Pentagon had no choice by to reprogram money from other operations and maintenance accounts, with the Pentagon estimating in January 2024 that an additional US$1.6-$2.2 billion would be required over the coming budget cycle to cover those unforeseen costs.69 That estimate came before the deployment of additional major surface combatants, including two carriers, ballistic missile submarines, multiple destroyers, and fighter squadrons to the region in mid-2024 in response to Houthi attacks on commercial shipping and several large-scale drone and missile attacks on Israel by Iran and Hezbollah.70

Though seemingly manageable in isolation, in reality these deployments compound with preexisting trends in two key areas. Firstly, these unforeseen deployments put additional pressure on already strained maintenance and sustainment programs. Several assets deployed on short notice to the Middle East were required to stay on station longer than intended, disrupting future deployment schedules and increasing their downstream maintenance costs.71 Secondly, these deployments fit into a much longer timeline of US efforts to right-size its regional military footprint, with efforts to downscale force commitments since the 2018 National Defense Strategy persistently disrupted by fresh crises. Indeed, the pattern of deployment, withdrawal and redeployment of high-end US missile defence, fighter aircraft and naval assets to and from Central Command since 2018 is instructive of the enduring drain of Middle East operations on US combat resources and, by extension, on its military industrial capacity (see Table 6). This pattern has occurred despite the evident consensus between the Trump and Biden administrations regarding the need to prioritise near-peer competition with China and Russia over operations in the Middle East.

Table 6. Select US deployments and withdrawals from the Middle East since 2018

c. Legacy readiness issues

Air Force and Navy maintenance backlogs

Many of the challenges afflicting the US defence industrial base predated the shocks of COVID, the war in Ukraine or renewed large-scale operations in the Middle East. Crucially for America’s position in Asia, its Air Force and Navy continue to grapple with acute maintenance, production and sustainment challenges. A May 2023 Government Accountability Office report on overall US military readiness showed that while the Army and the Marine Corps had improved their maintenance rates over the preceding decade, the Navy and the Air Force continued to struggle. For example, 47 of 49 aircraft classes surveyed failed to meet mission capability goals between 2011 and 2021 due largely to supply chain shortages and unplanned or delayed maintenance requirements, with aerial refuelling, cargo and fighter classes faring the worst.91 The F-35 Joint Strike Fighter has suffered in particular, with sustainment costs having increased by nearly 50% since 2018 even with reductions in flight hour estimates and other cost- and readiness-saving measures, while overall fleet readiness has struggled to exceed 60%.92

For the Navy, the increasing costs of maintaining primary surface combatants — destroyers and cruisers — have been compounded by major parts shortages and delays associated with both scheduled and unscheduled maintenance.93 For instance, a separate GAO report in January 2023 noted that maintenance costs for a range of primary surface vessel classes increased by 25% between 2011 and 2020, even as the number of operational days for these same vessels decreased and instances of cannibalisation — borrowing parts from other assets rather than using new ones — had increased.94 While some improvements have been made — 59% of vessels completed their maintenance on time in FY21, compared to 29% in FY1995 — maintenance backlogs still figure as a major check on credible US naval power projection in Asia, putting a new premium on defence industrial collaboration with allies and partners to sustain a persistent and credible presence.96

The submarine maintenance and construction crunch

Of particular interest to Australia is the construction and sustainment crunch afflicting the US Navy’s nuclear-powered attack submarine (SSN) fleet. Though these challenges predated the September 2021 AUKUS agreement, they have received a high degree of scrutiny as the pathway for delivering Australia’s SSN capability through Pillar I has taken shape. On maintenance, in 2023 the Congressional Research Service highlighted the steady increase in the number of US SSNs in depot maintenance or sitting idle as a percentage of the Navy’s total inventory between 2012 and 2022, with a third of the total submarine fleet out of action at any given time.97 Even as the overall force size remained relatively consistent across the decade, maintenance-related delays produced a corresponding decrease in the number of submarines available for deployment, due to workforce shortages and facility limitations.

Importantly, the same challenges that have produced SSN maintenance backlogs have compounded with efforts to increase submarine production to the level required to meet both Australian and US fleet requirements. The Navy’s own “comprehensive shipbuilding review” released in April 2024 uncovered significant delays to both SSN and SSBN programs,98 with supply issues for key components producing 12-16 month delays to the Columbia program this year and 2-3 year delays for the most up-to-date models of Virginia-class submarines.99 While the Pentagon is proceeding with both programs under a ‘2+1’ production schedule — 2 SSN and 1 SSBN per year — senior Navy officials have repeatedly stressed that the Columbia-class remains the Navy’s singular top acquisition program, meaning that it would receive priority when it comes to allocating industrial or workforce resources relative to the Virginia-class program.100 Indeed, a GAO January 2023 report noted that the priority status afforded to the Columbia-class program, and the tight window for seamlessly replacing the US Navy’s existing SSBN fleet, had already resulted in shipbuilding staff originally assigned to Virginia-class construction being re-tasked, contributing to delays for that program. It also noted that long-term planning for both programs did not account for these sorts of shared risks “that are likely to present production challenges and could result in additional costs.”101

There is evident disagreement across the US system regarding the capacity of the submarine industrial base to take on additional work, let alone deliver on its current assignments.

The Biden administration moved to shore-up the submarine industrial base, with help from Australia. Yet there is evident disagreement across the US system regarding the capacity of the submarine industrial base to take on additional work, let alone deliver on its current assignments. On top of the US$3.3 billion for the submarine industrial base passed in the long-delayed National Security Supplemental in April 2024 and a one-off US$3 billion investment by Australia in that same year, the administration’s FY25 budget request proposed US$3.9 billion for next financial year and a further US$11.1 billion across the coming five years to retool the US submarine industrial base to meet its new requirements.102 However, Congress insisted on adding a second submarine to the final FY25 National Defense Authorization Act, an acquisition that the Biden team had omitted from its request citing current industrial capacity limitations.103 This was met by a warning from Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin in October 2024 that funding an additional submarine in FY25 would quickly run-up against the realities of the production limitations of the submarine industrial base and make some of the Navy’s other capability modernisation priorities, including its next-generation fighter jet, “unexecutable.”104 Following an additional supplemental funding request in November 2024 for USD7.3 billion in submarine construction costs — nearly 80%of which would go towards Virginia-class cost overages — Congress expressed concerns about the Navy’s “lack of transparency” with the Hill and with the Office of Management and Budget about significant cost growths associated with SSN production, alleging that Congress was left “with few options to address this situation and likely none that will rectify it going forward.”105

d. Contested logistics

Crucially, it has also become increasingly apparent that simply enhancing America’s own defence industrial and technological outputs will be insufficient to counteract China’s growing military capabilities in the Indo-Pacific. Given the well-established challenges facing US air and naval maintenance and sustainment and a growing appetite for munitions of all kinds amongst frontline allies and partners worldwide, American defence officials are increasingly cognisant of the value that US allies and partners’ defence industrial capabilities — not just their access locations — can bring to bear in support of a resilient collective deterrence strategy and, potentially, in a range of imaginable high-end conflict scenarios.

The problem is both one of capacity and geography. American logistics and resupply capabilities need to traverse great distances of open water or air space between the continental US to reach major operating locations on US Pacific territories or allied nations, leaving them highly vulnerable to disruption by adversaries’ anti-access and area denial systems, particularly subsurface and long-range strike capabilities. Though not an entirely novel challenge in the Indo-Pacific — General Douglas McArthur observed during the Pacific campaign in the Second World War that “[v]ictory is dependent upon the solution of the logistics problem” — it is one which looms as a key determinant of the credibility of US regional military strategy. Unlike bygone decades, the United States can no longer assume that it will have the freedom to “resupply forces carrying out high-tempo operations without fear of disruption,”106 particularly when top US military officials have characterised the regional balance of power as one increasingly unfavourable to American interests.107 These trends have placed a heightened premium not only on improving the survivability and distribution of US regional force posture but also on ensuring that dispersed units can continue to receive sufficient logistics and material support.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, top US military leaders have identified credible military logistics capabilities as “the key element of integrated deterrence” in Asia,108 and the challenge of maintaining and sustaining US forces in this increasingly contested strategic space is one which has been identified as a “gigantic problem” by US military logisticians.109 Indeed, while Chinese military capabilities necessitate the dispersal of operating locations away from large concentrated bases in Japan and South Korea, analysts have noted that such a distributed network of smaller bases may not prove to be any more resilient than present arrangements without means of adequate sustainment.110 Furthermore, recent unclassified wargames have spotlighted “a lack of practical clarity” over how the US Joint Force would execute its logistics concepts across the region, even as these capabilities become an increasingly attractive target for would-be adversaries.111 It is in that context that US officials and military planners have increasingly looked to regional allies and partners to sustain US combat power in new ways, including through shouldering maintenance and production requirements. In theory, access to robust allied defence industrial bases could allow Washington to “shorten the tail” between US combat units and their logistics and sustainment providers, thus increasing their resiliency and persistence.112

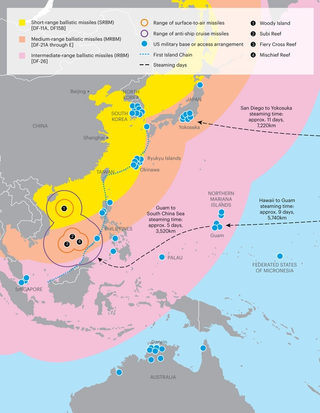

Figure 1. China’s growing missile threat to US bases and regional access locations

2. Advancing integration with allies and major partners in Asia

To offset these myriad challenges, the United States has increasingly turned to major allies and defence partners in the Indo-Pacific. Importantly, these efforts have gone beyond prevailing concepts of dispersing and diversifying the number of operating locations available to US forces across the region or improving the interoperability of combined forces. Rather, recent years witnessed Washington and its allies take notable strides towards integrating maintenance, repair, overhaul and co-production into their respective alliance or partnership defence arrangements.

To that end, among the hallmarks of the Biden administration’s approach to alliances and partnerships in the Indo-Pacific were its efforts to advance discrete defence industrial and technology projects with its primary regional treaty allies and major defence partners: namely, Australia, India, Japan and South Korea. In doing so, the Biden administration proved relatively receptive to the proposals and requirements of its allies and partners, both in terms of ‘stepping out’ of the way of these countries’ attempts to self-strengthen in the interests of collective security, as well as ‘stepping in’ to new and existing mechanisms intended to advance defence cooperation, including on industrial and technology issues.113 Those developments can be broadly divided into three primary categories: developing greater in-theatre maintenance, repair and overhaul (MRO) capacity through facilities and workforce development; pursuing co-production arrangements for in-demand defence items, particularly munitions; and advancing new and existing defence technology co-development arrangements.

Recent years witnessed Washington and its allies take notable strides towards integrating maintenance, repair, overhaul and co-production into their respective alliance or partnership defence arrangements.

a. Australia

It is arguable that Australia has become the poster child for US-allied defence industrial and technology integration. While AUKUS has dominated much analysis since its inception in September 2021, a broader suite of defence industrial and technology activities has redefined the art of the possible within a modern alliance framework.

Maintenance, repair and overhaul

Over the last four years, logistics and maintenance collaboration have assumed a greater place in the growing Australia-US defence cooperation agenda. The Biden administration’s first Australia — United States Ministerial Consultations (AUSMIN) in 2021 saw the announcement of the Combined Logistics Sustainment and Maintenance Enterprise (CoLSME),114 intended to enhance responses to regional crises, bolster the interoperability of capabilities, support logistical challenges and opportunities in-theatre, promote defence infrastructure and improve the maintenance of fit-for-purpose capability.115 The 2021 announcement was followed by logistical preparation “to support tactical operations,” which notably included support for Marine Force Rotations in Darwin (MRF-D) and the prepositioning of US Army equipment to support joint training and exercises in Bandiana, Australia.116 At AUSMIN 2023, Australian and American leaders announced plans to establish a permanent Logistics Support Area in Queensland.117 Analysts posited these developments as essential for improving combined defence industrial preparation by enabling faster, more coordinated and more resilient response options to potential regional contingencies.118

Washington and Canberra have also taken steps to deepen naval MRO cooperation, with a particular focus on naval aviation and subsurface combatants. This has included certifying local Australian businesses to conduct deeper levels of maintenance and sustainment on common platforms, such as the P-8A Poseidon and MH-60R Seahawk ‘Romeo’ helicopter. In 2022, modification works were carried out at the Royal Australian Air Force’s Base Edinburgh near Adeline to enable Boeing Defence Australia to complete in-country maintenance on its own — and potentially US — P-8A fleet.119 The completion of these works provided an instant uplift to allied maintenance capabilities in-theatre, with the entire fleet of aircraft able to be maintained to a greater quality and at a greater cadence in-country, rather than having to transport the fleet to the United States to do so. From 2023, for instance, Sikorsky Australia was certified to complete “periodic maintenance inspection[s]” of US Navy MH-60R,120 effectively providing a new option for in-theatre maintenance on a key capability.121 These developments were framed by Australian military officers as spotlighting underutilised avenues for MRO collaboration across the region for key US decision-makers.122

Importantly, 2024 saw maintenance conducted on a US Navy nuclear-powered submarine USS Hawaii at HMAS Stirling in Western Australia, performed by US and Australian Navy crew from the USS Emory S. Land and personnel from Royal Australian Navy (RAN) Fleet Support Units.123 The Submarine Tendered Maintenance Period (STMP) was completed over multiple weeks, with US crew members largely providing support and supervision for their Australian counterparts, marking the first time since the Second World War that US submarine maintenance had been conducted in Australia, and was the first time a combined American-Australian team had performed maintenance on a nuclear-powered attack class submarine (SSN).124 It also represented a significant improvement in Australia’s ability to maintain and sustain SSNs ahead of receiving its own SSN fleet through AUKUS beginning in the 2030s.125

Co-production and supply chains

Washington and Canberra also sought to advance or introduce a number of co-production and defence industrial supply chain initiatives, particularly in relation to the Guided Weapons and Explosive Ordnance (GWEO) enterprise. Originally announced in Australia in 2020, under the Biden administration, the partners sought to “institutionalise US cooperation” within GWEO,126 to the extent that the enterprise now figures as a discrete alliance initiative.127 Institutionally, this has involved the creation of a “multi-service roadmap” to guide ambitious development plans, and the planned establishment of a Joint Programs Office in 2025.128 In practical terms, this has focussed largely on co-producing GMLRs in Australia by 2025 based on the achievement of various co-assembly and co-production milestones, including an agreement from Washington to transfer essential technical data to Australia to support those objectives.129 Though criticised for their limited relevance to the Indo-Pacific theatre, officials on both sides have framed the GMLRs project as a “pipe cleaner” to streamline cooperation on more relevant models of missile. Indeed, to that end officials have already announced an additional GWEO project focussed on producing PRsM short-range ballistic missile training rounds.130 Notwithstanding these positive developments, there remain challenges associated with scale and speed. For example, consternation remains about just how robust the business case is for producing GMLRS in Australia,131 including challenges associated with building local economies of scale at price points attractive to Australian and US customers alike.132 While this issue could be alleviated by more significant US investment in Australian production, there is an ongoing question about how politically feasible this is for US interlocutors given protectionist pressures and (likely cheaper) domestic alternatives.133

Defence technologies

Perhaps among the Biden administration’s most notable alliance modernisation initiatives was the AUKUS (Australia-UK-US) technology sharing agreement. Announced in September 2021, AUKUS comprises two key lines of effort: the delivery of Virginia-class and, later, AUKUS-class nuclear-powered submarines to Australia in the 2030s and 2040s under Pillar I; and the rapid development of advanced asymmetric capabilities under Pillar II.134 Most notably, March 2023 saw the release of the ‘Optimal Pathway’ for Pillar I, the roadmap for the development and delivery of AUKUS submarines.135 Insofar as technology co-development is concerned, the optimal pathway outlines three distinct phases leading up to Australia and the UK’s SSN-AUKUS acquisition, to be based on UK design and incorporating technology from all three nations, and inclusive of a bespoke technology-sharing memorandum between the all three countries authorising the sharing of sensitive nuclear propulsion technology with Australia.136

Technology sharing and co-development efforts have also progressed through Pillar II. These activities have focussed largely on improving the interoperability and interchangeability of existing advanced capabilities operated by all three countries, many of which have had distinct maritime domain applications.137 In 2024, for instance, the AUKUS partners deployed common advanced artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms on their respective P-8A Maritime Patrol Aircraft, enabling more rapid data processing, information-sharing and target identification in “congested acoustic environments.”138 Relatedly, the three countries have sought to “scale up” the integration of torpedo-launched unmanned system capabilities onto current UK and US (and future Australian) submarines, integrating UK Sting Ray lightweight torpedoes onto P-8A alongside standard US Mk 54 variants to enhance interchangeability, and testing quantum clocks for maritime position, navigation and timing purposes.139 Elsewhere, the AUKUS partners conducted several artificial intelligence (AI) and autonomy demonstrations, with the intention of supporting better decision-making and improving combined military effects such as enhanced target location for unmanned land and air systems.140 In November 2024, the three countries announced the Hypersonic Flight Test and Experimentation (HyFliTE) Project Arrangement to facilitate the use of one another’s hypersonic testing facilities and the greater sharing of technical information to “develop, test, and evaluate hypersonic systems,”141 effectively linking existing national and collaborative hypersonic weapon testing programs.

The AUKUS partners have also sought to establish forums for identifying and soliciting the best defence-relevant technologies on offer in all three countries, and for engaging prospective fourth parties to the overall agreement. Foremost among these was the 2024 Maritime Big Play series — described by officials as the Australian version of the US DoD’s Rapid Defense Experimental Reserve program — an initiative focused on domain-specific rapid technology pull-through and modernisation.142 This series involved an “integrated experiments and exercises… designed to enhance capability development and improve interoperability,” including the joint operation of uncrewed maritime systems and the sharing and processing of real-time maritime domain awareness data.143 For Australian dual-use companies, Maritime Big Play offered the chance to have technology evaluated by operators and officials from all three AUKUS countries, demonstrating Pillar II is concerned with providing opportunities for three-way technology transfer.144 These opportunities built on the initial successes of AUKUS electronic warfare innovation challenges in all three countries, activities which had the effect of spotlighting world-class capabilities on offer in Australia, in particular, to the surprise of Canberra and Washington alike.145

AUKUS has also driven parallel efforts to reform US defence technology sharing regulations and to harmonise allies’ own policy settings with Washington’s. This included major (though incomplete) exemptions for Australia and the UK from licensing requirements of the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR) and the Department of Commerce’s Export Administration Regulations (EAR),146 carveouts long sought by Australian governments and industry alike. These reforms were accompanied by changes to Australian regulations to bring them into closer alignment with American standards, encapsulated in the Defence Trade Controls Amendment Act 2024 and Defence Trade Legislation Amendment Regulations.147 These measures were designed to streamline defence trade between the 3 countries through the removal of requirements for about 900 export permits, or about AU$5 billion annually from Australia to the United States and the United Kingdom, in the interests of facilitating greater technology sharing through AUKUS Pillar I and II as well as the alliance’s wider array of defence industrial initiatives.148 In that respect, as the authors have summarised elsewhere, AUKUS Pillar II has become as much about procedural and regulatory reform as it has capability development.149

Canberra and Washington also sought to advance trilateral defence technology cooperation with Japan. For instance, in May 2024 the three countries concluded a trilateral Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation (RDT&E) Projects Arrangement to facilitate “operationally relevant advanced cooperation” on capabilities of mutual interest, including collaborative combat aircraft, autonomous systems and composite aerospace materials.150 Meanwhile, Japan also participated as an observer in Exercise AUTONOMOUS WARRIOR within the Maritime Big Play series, a step towards facilitating Japan’s initial engagement with AUKUS through honing unmanned maritime system interoperability.151

Beyond AUKUS and the trilateral with Japan, Australia and the United States continue to make progress on hypersonic weapons development through the Southern Cross Integrated Flight Research Experiment (SCIFiRE) which commenced in 2007. This work includes research on hypersonic scramjets, rocket motors, sensors, and advanced manufacturing materials.152 At AUSMIN 2024, Australian and US officials welcomed progress on the buildout of a hypersonic weapon under the SCIFiRE program and communicated their support for the testing of Hypersonic Attack Cruise Missiles by the US and Australian Air Forces,153 in anticipation of fielding the capability aboard the Royal Australian Air Force’s F/A-18F fleet.154

b. Japan

Though somewhat slow to start compared with other key alliances and partnerships, US-Japan cooperation on defence industrial and technology initiatives has gradually intensified over the last four years.

Maintenance, repair and overhaul (MRO)

Enhancing MRO capabilities for US assets forward deployed to Japan has become a major alliance initiative since early 2023. This push was spearheaded by Washington’s then-ambassador, Rahm Emmanuel, who repeatedly pitched Japanese private shipyards already conducting fleet maintenance for Japanese warships as essential means for improving the overall readiness of US forces in the Indo-Pacific and, to a lesser extent, as a source of additional shipbuilding capacity for the US Navy.155 Emmanuel framed such cooperation as essential both for shoring up deterrence in peacetime and for offsetting contested logistics challenges in prospective future crisis scenarios, citing the extensive repair backlogs afflicting US surface and subsurface fleets alike.156 Indeed, while US Military Sealift Command vessels have occasionally been repaired at Japanese shipyards, historically, US warships deployed to Japan have only been able to access basic maintenance capabilities at established US bases in Yokosuka and Sasebo, and have had to return to the US mainland for deeper maintenance and overhaul.

There have already been notable signs of progress. Most notably, the US-Japan April 2024 Leaders’ Summit formalised the alliance’s new focus on MRO. Firstly, it marked the establishment of the Forum on Defense Industrial Cooperation, Acquisition and Sustainment (DICAS) — jointly administered by the Office of the US Undersecretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment and Japan’s Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics Agency — which included dedicated task groups focussed on MRO and co-sustainment opportunities for forward-deployed US Navy ships and US Air Force fourth-generation aircraft at Japanese commercial facilities. These discussions have already produced an initial agreement reached in May to allow Japanese companies to service US F-15 and F-16 aircraft in Japan beginning in 2025 (on top of F-35 and F-18 aircraft already eligible), removing requirements for the aircraft to be flown to South Korea for routine maintenance.157 The administration also signalled its intent to work with Congress to smooth the legal and regulatory architecture for greater naval MRO in Japan, seeking the necessary authorisations for Japanese shipyards to conduct maintenance and repairs of 90 days or less on US Navy ships homeported in US homeland facilities deployed to the region, and to “review opportunities to conduct maintenance and repair of forward-deployed U.S. Navy ships at Japanese commercial shipyards.”158 This built on additional groundwork laid earlier in 2024, including the establishment of the Ship Repair Council Japan in January 2024 between the US Navy, JMSDF and industrial partners from both countries to identify opportunities for naval MRO work at Japanese commercial shipyards.159

US officials have also suggested that Washington will encourage Japan to extend access to its shipyards for MRO purposes to “friendly third countries such as the U.K. and Australia” once bilateral initiatives have proven effective.

Importantly, both Tokyo and Washington have shown an interest in potentially minilateralising MRO collaboration with third parties. In March 2024, a US delegation featuring senior Pentagon, Joint Staff and Defense Logistics Agency officials visited Japan as part of a wider regional tour to identify opportunities for “establishing a network of regionally aligned maintenance, repair, and overhaul capabilities,”160 while US Secretary of the Navy Carlos Del Toro visited several Japanese shipyards for discussions on “attracting Japanese investment in integrated commercial and naval shipbuilding facilities in the United States.”161 Indeed, US officials have also suggested that Washington will encourage Japan to extend access to its shipyards for MRO purposes to “friendly third countries such as the U.K. and Australia” once bilateral initiatives have proven effective.162

Co-production and supply chains

Concurrently, Tokyo and Washington have sought to deepen cooperation on critical defence supply chains, particularly air defence munitions. This included establishing new agreements and forums for facilitating cooperation, as well as seeking to remove barriers to exports and transfers of defence capabilities and technologies between the two countries. For example, in December 2023 Japan made the first major revisions to its Three Principles on Transfer of Defense Equipment and Technology since 2014 in order to facilitate the reexport of defence items produced in Japan under foreign license back to their place of origin, with the initial objective of increasing exports of Patriot PAC-2 and PAC-3 interceptors to the United States.163 Though this decision was framed by the Pentagon as intended “to replenish U.S. inventories,”164 it also came in the context of Washington’s efforts to ramp up the supply of air defence capabilities and munitions to Israel and Ukraine, and on the back of discussions between President Biden and Prime Minister Kishida Fumio in August 2023,165 demonstrating a role for regional allies in materially supporting US global security objectives without necessarily deploying forces. Additionally, Japan and the United States entered into a Security of Supply Arrangement (SoSA) in late 2023, creating a mechanism for both sides to “request expedited handling of industrial resources” to meet national and mutual “national security needs.”166

On the back of those developments, Tokyo and Washington have sought to engage further on defence supply chain and production cooperation opportunities through DICAS. Indeed, one of four working groups within this arrangement is explicitly tasked with identifying pathways and opportunities for the “co-development and co-production of missiles,”167 with the AIM-120 air-to-air missile and PAC-3 missile interceptor identified as pilot projects in late 2024.168 Indeed, then-Ambassador Emmanuel framed DICAS explicitly in the context of shrinking US industrial capacity and global demand pressures for munitions of all types in Europe and the Middle East,169 placing a clear premium on the rapid development of extra production capacity and output — and the extent to which long-standing barriers including technology transfer restrictions could be reformed — as the measure of DICAS’s success.170

Defence technologies

Defence technology development occupied a prime position in US-Japan defence industrial and technology cooperation under the Biden administration. Beyond the new trilateral defence technology cooperation initiatives with Australia discussed above, Japan and the United States have also sought to advance new bilateral defence technology co-development projects of their own. This involved updating or establishing the primary legal mechanisms used for such cooperation. At the first US-Japan Security Consultative Committee (or “2+2”) of the Biden team’s first term in May 2021, Tokyo and Washington finalised an Exchange of Notes on enhanced security measures for classified military information related to Advanced Weapon System, as well as an Exchange of Notes on Cooperative Research, Development, Production and Sustainment as well as Cooperation in Testing and Evaluation,171 a precursor to the January 2023 Memorandum of Understanding for Research, Development, Test and Evaluation Projects (RDT&E),172 marking a significant upgrade in the alliances defence technology cooperation architecture.

These developments helped to advance tangible cooperation on discrete defence technology initiatives. From May 2021, Tokyo and Washington steadily established a new initiative to develop counter-hypersonic weapons capabilities, culminating in the finalisation of a formal Glide Phase Interceptor (GPI) Cooperative Development research and development agreement in May 2024.173 This arrangement was framed explicitly in the context of long-standing US-Japan collaboration on air and missile defence projects,174 most notably the co-development and production of the Standard Missile-3 Block IIA beginning in 1999,175 and Japan’s purchase of Aegis Ballistic Missile Defence systems for the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force and Aegis Ashore variant in 2017 (though scrapped by Tokyo in 2020).176 Importantly, these developments also came about after Japan made explicit requests to the office of the US undersecretary of defence for research and engineering in October 2021 for greater defence acquisition and technology collaboration, including on hypersonic capabilities, in the interests of upgrading the overall alliance relationship.177

c. India

The Biden administration also made notable strides in advancing a range of defence industrial and technology initiatives with India, with the goal of “strengthening India’s capabilities, enhancing its indigenous defense production, facilitating technology-sharing, and promoting supply chain resilience.”178 It sought to do so by leveraging both existing mechanisms like the Defence Trade and Technology Initiative (DTTI), as well as through new initiatives like the India-US Defense Acceleration Ecosystem (INDUS-X) and the Defense Innovation and Technology Cooperation branch of the January 2023 Critical and Emerging Technology (iCET) initiative.179 These efforts have been cohered within the June 2023 US-India Defence Industrial Roadmap, intended as interim guidance pending updates to the 2015 Framework for the US-India Defense Relationship.180

Maintenance, repair and overhaul (MRO)

Interestingly, US-India cooperation on MRO has outstripped equivalent lines of effort in America’s treaty alliances with Australia, Japan and South Korea. This has been particularly noteworthy with respect to naval MRO, a priority in US efforts to “to make India a [military] logistic hub for the United States and other partners in the Indo-Pacific region.”181 An initial principals’ agreement in April 2022 to explore utilising the Indian shipyards for mid-voyage repair and maintenance of US Maritime Sealift Command (MSC) vessels was quickly operationalised in August 2022, when the dry cargo ship USS Charles Drew docked at Larsen & Toubro’s (L&T) Shipyard in to fulfill a one-off ship repair and maintenance contract,182 followed up with repairs to the USNS Matthew Perry in March 2023.183 These arrangements were cemented over the next year with the signing of the three five-year Master Ship Repair Agreements (MSRA) between the US Navy and L&T, Mazgaon Dock Shipbuilders, and Cochin Shipyard Limited, respectively, between July 2023 and April 2024,184 with fourth and fifth shipyards at Kolkata Port and Goa Shipyard Ltd reportedly under consideration for similar agreements.185

Efforts to expand India’s MRO capacity have also extended to naval aviation, capitalising on a long-standing vector for enhancing US-India — and, for that matter, India-Australia and India-Japan — military interoperability through sales of manned and unmanned systems.186 For example, Indian company Air Works and US company Boeing established the Boeing India Repair Development and Sustainment (BIRDS) hub in February 2021 to greatly enhance India’s capacity to conduct depot level inspections, including heavy maintenance and service checks, on Boeing-made P-8I Poseidon maritime patrol aircraft operated by the Indian Navy and the VIP transport fleet operated by the Indian Air Force,187 services which Air Works hopes to extend to the Australian and New Zealand defence forces in coming years.188 Similar industrial partnerships have been built-out to support India’s acquisition of 31 MQ-9B unmanned aerial systems from the United States.189 In February 2023, Indian state-run enterprise Hindustan Aeronautics Ltd was certified to provide MRO services for engines of American MQ-9B aircraft,190 while the development of local MRO support in India was included in the final contract between India and General Atomics announced in October 2024.191

Co-production and supply chains

Greater collaboration on MRO synergised with parallel efforts to enhance co-production for US-origin systems and components in India, including in aviation and munitions, after a decade of piecemeal progress under the 2012 DTTI.192 Progress here has been enabled through a combination of enhanced technology sharing and localised production agreements. For example, the United States and India negotiated notable increases to the percentage of Indian-made electronics, sensors, avionics and other componentry that would be included in its future MQ-9B fleet.193 The Indian Government also reportedly sought agreement that 21 of its 31 platforms would be assembled at Indian facilities along with attendant technology transfer authorisations, in the interests of establishing a Sea Guardian Global Sustainment (SGSS) Hub in India to provide MRO support for MQ-9 drones operated by friendly powers in the Indo-Pacific.194 In addition, an agreement struck between American company General Electric (GE) and India’s Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL) will see the former transfer 80% of technologies involved in the production of F414 engines transferred to the latter, a marked increase from 58% transfer rate proposed as part of a previous Engine Development Agreement in 2012, to support the development of India’s Light Combat Aircraft (LCA)-MK2.195 Aside from facilitating more efficient MRO, the deal is also expected to pave the way for transfers of other jet engine technologies and manufacturing capacity to India.

Washington has also increasingly turned to India for cooperation on munitions production and supply chain security. As part of a wider effort to offset shortfalls in US explosives, energetics, primer and fuse production by tapping global partners, the US Army awarded multi-year contracts to Indian companies for the production of 155mm shell componentry in October 2023.196 In June 2024, the National Security Advisors of both countries also flagged a new strategic semiconductor partnership between General Atomics and 3rdiTech to “co-develop semiconductor design and manufacturing for precision-guided ammunition and other national security-focused electronics platforms.”197 This would seemingly support ongoing negotiations over the production of Javelin anti-tank missiles in India to support its own requirements,198 a discussion which has waxed and waned for over a decade due to US restrictions of technology sharing and, as a result, India’s decision to purchase equivalent systems from other suppliers with more favourable technology transfer provisions.199 Importantly, these discussions are occurring at the same time as India has drastically reduced its imports of many types of ammunition from overseas,200 most notably from Russia.201

Defence technologies

Washington has also sought to advance defence technology co-development initiatives with India, focused on discrete capability development projects and creating a more permissive and connected ecosystem between US and Indian defence technology innovators. For example, after over a decade of stalled efforts to identify and commence joint projects, in July 2021 the Pentagon and India’s Ministry of Defence announced the inaugural project agreement for air-launched unmanned systems through the DTTI,202 including arrangements to facilitate joint intellectual property ownership and sales to third parties.203 This was followed by the identification of a further two DTTI projects focused on counter drone systems and intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) platforms in February 2023.204 Concurrently, through the Defense Innovation and Technology Cooperation branch of the iCET initiative announced by Biden and Narendra Modi in January 2023, the two countries pursued additional bespoke co-development and co-production projects focussed on driving near-term collaboration on “jet engines, munition related technologies, and other systems” and longer-term cooperation on capabilities with “maritime security and [ISR] operational use cases.”205 The two sides also sought to better connect their defence business communities, establishing the INDUS-X mechanism to better connect US and Indian defence start-ups,206 with initial collaborations focussed on autonomy and ISR in the air and maritime domains announced in February 2024.207 Both countries have pursued these efforts in the wider context of deepening their collective capacity for “precision warfare” in the maritime environment, chiefly “through the integration of modern sensors, munitions, and artificial intelligence.”208

d. Republic of Korea

Defence industrial and technology collaboration only really assumed prominence in the US-Korea alliance with the advent of the Yoon Suk-yeol administration in Seoul in May 2022, having featured only sparingly in joint communications until that time.209 In recent years, however, these issues have been identified as central to enhancing “interoperability and interchangeability within the Alliance defense architecture,”210 with the November 2023 Defense Vision of the US-ROK Alliance underscoring optimised defence industrial cooperation and enhanced supply chain resiliency as top priorities going forward.211

Maintenance, repair and overhaul (MRO)

Korea and the United States have identified MRO collaboration as a priority for “enhancing the Alliance’s posture and capabilities,” including in the context of developing distributed readiness capabilities in a contested logistics environment.212 Notably, this has included a shift in arms sales practices to include industrial upskilling provisions in recent FMS sales of US capabilities to South Korea, with the intention of facilitating greater in-country MRO of US-origin capabilities operated by both countries’ forces. For example, as part of a December 2023 deal to purchase 20 F-35 fighter aircraft, the ROK Air Force announced in April 2024 that it would establish a heavy maintenance and repair depot at Cheongju Airbase by 2027, removing requirements for ROKAF F-35 aircraft to be flown to Australia for deep maintenance.213

Defence industrial and technology collaboration only really assumed prominence in the US-Korea alliance with the advent of the Yoon Suk-yeol administration in Seoul in May 2022, having featured only sparingly in joint communications until that time.