Key takeaways

- In the face of COVID-19’s challenges, the Biden administration kept its promise to reinvigorate diplomacy in its first 18 months in office. However, it did not surpass some quantitative standards for engagement with the Indo-Pacific set by its predecessors.

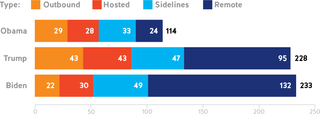

- President Biden, Secretary Blinken and Secretary Austin undertook a combined 233 engagements (meaning diplomatic interactions with counterparts in any form) with the Indo-Pacific over their first 18 months. This narrowly exceeds the Trump administration’s 228 engagements over the same duration and the 114 engagements attested to by available Obama administration records.

- The Biden administration stands apart from its predecessors for its consistent regional summit attendance and 49 associated sidelines meetings, where the Trump administration had held 47 and the Obama administration convened 33 over an equal period in the absence of pandemic conditions.

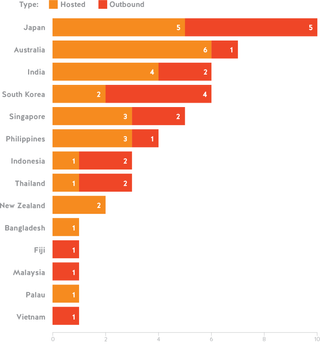

- President Biden and his appointees performed strongly in securing meetings with traditional democratic allies in the Indo-Pacific. Australia is among the nations that have benefited the most from the administration’s renewed diplomatic efforts. More senior Australian officials have been hosted by their US counterparts than from any other country.

- Wider regional engagement, particularly with Southeast Asia, was delayed and negligible at the presidential level in the administration’s first 18 months. Unlike both of his predecessors, President Biden held no phone calls and conducted no foreign visits to Southeast Asian countries in his first year.

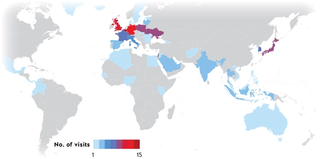

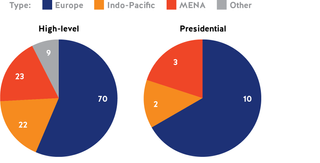

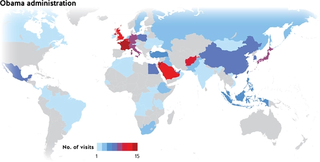

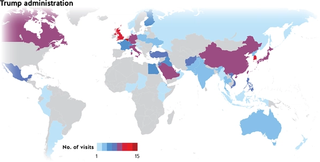

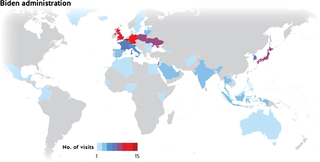

- The 22 visits President Biden, Secretary Blinken and Secretary Austin undertook to Indo-Pacific countries were surpassed more than three times over by their 70 visits to Europe – in no small part attributable to Europe’s geographical proximity to the United States, looser pandemic-based border restrictions, more institutionalised alliances and the administration’s efforts to build an international coalition answering Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

- President Biden himself took 16 months to make his first visit to the Indo-Pacific, while he was a regular visitor to Europe throughout his first 18 months in office. He also hosted 11 meetings with European heads of state in Washington DC, while only hosting seven meetings with Indo-Pacific leaders.

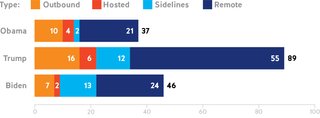

- In addition to his limited travel to the region, which is unsurprising given the constraints of the pandemic, President Biden’s digital engagement with regional heads of state was also subdued. He made only 24 calls to Indo-Pacific counterparts over 18 months, where President Trump held 55 and President Obama held 21.

Introduction

Since entering office, the Biden administration has embraced its predecessors’ view that the Indo-Pacific is the priority theatre for US foreign policy.1 President Biden and his foreign policy advisors advance that the United States is a resident power in the region and acknowledge that a consistent US presence is a strategic necessity. Promising that “diplomacy is back,” senior administration officials have engaged critical regional allies and partners diplomatically through an array of avenues.2 High-level meetings are an economical and highly visible affirmation of US intent for its strategic relationships.

In advance of the upcoming Asian summit season, this policy brief reflects on US high-level diplomacy in the Indo-Pacific since the Obama administration’s “pivot” to the region was announced. Its findings emerge from a quantitative catalogue of 1,128 diplomatic meetings held across the Obama, Biden and Trump administrations. It begins by assessing the diplomatic activities of the Biden administration’s most senior diplomats: the President, the Secretary of State, and the Secretary of Defense.3 It then compares the frequency, seniority, and distribution of these international engagements with those held by their predecessors during the first 18 months of the Trump administration and the first 18 months of President Obama’s second term.4 It concludes by contrasting US diplomacy in 2020 and 2021 to evaluate the impact of COVID-19 on high-level engagement with the Indo-Pacific.

The Biden administration is the only administration in recent years to have maintained a perfect attendance record at the major annual regional summits.

In the face of an array of challenges, the COVID-19 pandemic foremost among them, the Biden administration should be commended for restoring predictability to the US diplomatic calendar in the Indo-Pacific. It is the only administration in recent years to have maintained a perfect attendance record at the major annual regional summits. President Biden and his cabinet appointees initiated novel or newly invigorated multilateral meetings, including with the Quad, the Pacific Islands countries, and ASEAN. The administration also performed strongly in strengthening its diplomatic relationships with its regional democratic allies Japan, South Korea and Australia.

Simultaneously, however, the administration has concentrated its diplomatic energies in Europe and presidential travel and phone call correspondence have been subdued. A hard task remains in reassuring Southeast Asian countries and sustaining emerging ties in the South Pacific. Delayed high-level visitation and an irregular lack of President Biden’s attention in parts of the region implied a lack of focus on the key region the administration purports to be most significant.5

Certainly, diplomatic engagements are a single, quantitative measure of prioritisation, and travel data is only one measure of diplomatic influence. Many additional qualitative metrics must be considered to evaluate the tangible reality of US efforts to uplift its regional allies. This is especially the case given that the pandemic prevented diplomatic travel from occurring as usual. Nevertheless, if the administration intends to substantiate its rhetoric of “firmly anchoring the United States in the Indo-Pacific,”6 sustained, high-level engagement is needed to demonstrate that the United States can show up for its partners.

1. Overall engagement with the Indo-Pacific across three administrations

In August 2021, a USSC report on US influence in the Indo-Pacific7 observed the Biden administration had restored normalcy by insistently reaffirming the value of regional partners and restoring policies to where they stood before Donald Trump’s presidency. However, the authors argued that the administration had not succeeded at advancing US standing or successfully competing for influence.

A year later, the scale and frequency of President Biden, Secretary Blinken and Secretary Austin’s diplomatic activities lend support to this assessment. To be sure, in their first 18 months in office, these officials reinforced high-level communication with Indo-Pacific partners, and the number of visits says nothing of their qualitative value. However, the Biden administration did not appreciably exceed the quantitative standard for US diplomatic efforts in the region set by its predecessors.

The 233 high-level engagements conducted by these Biden administration officials in their first 18 months narrowly exceeded their Trump administration predecessors’ 228 engagements over their initial period. The Trump administration’s diplomatic engagements became increasingly sporadic as time went on, making the regular diplomatic communication regional partners now expect from Biden administration officials especially reassuring.

Figure 1.1 Total Indo-Pacific engagement in an administration’s first 18 months8

Definitions of key terms

'Outbound' refers to diplomatic travel by an administration official to conduct a visit outside of the United States.

'Hosted' refers to a diplomatic meeting convened by one of the officials of interest with an equally senior official from a foreign country.

'Sidelines' refers to a meeting between an administration official and a foreign counterpart convened on the margins of a larger multilateral summit.

'Remote' refers to the conduct of two categories of virtual diplomacy: phone calls and digital summits.

The Biden administration’s first year and a half of Indo-Pacific diplomacy was particularly strong in three areas: summit attendance, sidelines engagement, and secretarial virtual dialogues. Firstly, President Biden, Secretary Blinken, and Secretary Austin stabilised and invigorated regional multilateralism. Other than the technical disruption to Secretary Blinken’s participation in his first ASEAN meeting in May 2021, administration officials’ attendance at major regional summits was uninterrupted. Further, administration officials engaged with partners in novel or newly invigorated configurations, including through the Quad, AUKUS, and the US-Japan-ROK (Republic of Korea) trilateral. Though, as Susannah Patton argued,9 the criticism for missing summits is usually louder than the praise for turning up, multilateral engagement provides a strong foundation for US influence in the region and reassures partners.

Secondly, President Biden and his appointees conducted uniquely extensive sideline engagement with Indo-Pacific partners around multilateral meetings. In the face of COVID-19’s obstacles to the convening of summits, the Biden administration performed particularly strongly in maximising dialogue opportunities during a single trip. This is especially remarkable given that key opportunities for sidelines diplomacy were cancelled in 2021, including the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore. Sidelines meetings with Indo-Pacific counterparts held in conjunction with European summits provide anecdotal evidence of the administration’s determination to “walk and chew gum”,10 sustaining its attention on both regions at once.

The Biden administration did not appreciably exceed the quantitative standard for US diplomatic efforts in the region set by its predecessors.

Thirdly, in the face of pandemic-related impediments to face-to-face meetings, Secretaries Austin and Blinken effectively transitioned their diplomacy to remote meetings. As Figure 1.1 shows, the Biden administration achieved parity with total Trump administration engagement with the region over 18 months through frequent high-level virtual meetings with Indo-Pacific countries. President Biden’s foreign secretaries attended the major Asian summits via teleconference, including the East Asia Summit and the US-ASEAN Ministerial Summit, and made regular telephone calls to counterparts reaffirming partnerships.

In other respects, however, the Biden administration did not increase the scale of US Indo-Pacific engagement. President Biden himself held fewer in-person and remote engagements with Indo-Pacific heads of state than President Trump in his first 18 months in office. President Trump held unusually frequent conversations with Japanese and South Korean leaders on matters related to North Korean nuclear activities. Subsequently, even with the forcing factor of COVID-19, President Biden’s phone calls to the region were far eclipsed by his predecessor. In fact, President Biden only narrowly exceeded the number of phone calls that President Obama conducted with Indo-Pacific countries in 2013 and 2014.

Certainly, health concerns, travel restrictions, and a need to prioritise domestic politics during the pandemic discouraged diplomacy as usual. Even accounting for pandemic conditions, however, the Biden administration’s presidential diplomacy and degree of focus on the region were less committed than under the Trump administration’s early months.

Figure 1.2 Presidential engagement with Indo-Pacific countries in their first 18 months

Judging by the frequency of their engagements in Europe versus the Indo-Pacific President Biden, Secretary Blinken and Secretary Austin remained more focused on Europe than their Trump administration predecessors throughout their first 18 months in office. This shift reversed some of the Trump administration’s efforts to refocus US diplomacy on Asia.

Considering US diplomacy at the country level, the Biden administration has been exceedingly promising for some states in the Indo-Pacific but mixed for others. Senior officials held unprecedented bilateral and multilateral meetings with Pacific Island countries, including Fiji, Palau and the Federated States of Micronesia. The most notable incidence, though beyond the period considered by this dataset, is the recent US-Pacific Island Country Summit hosted in Washington DC.11 In this respect, the administration successfully followed through on its Indo-Pacific Strategy in that it “strengthen[ed] US commitment”12 to the Indo-Pacific at large, outside of its traditional alliances.

Yet while determined to engage the region at large, the Biden administration has placed a premium on restoring and fortifying traditional alliances, in Asia and other regions. It is Australia that was, quantitatively, the greatest beneficiary of the Biden administration’s renewed diplomatic efforts. High-level administration officials held 32 high-level meetings with Australian counterparts, compared with the 17 and 14 held by the Obama and Trump administrations respectively over an equal period. The Biden administration's total represents a 56 per cent increase from the Trump administration’s early record. This occurred even though the US-Australia fared reasonably well under the Trump presidency. The extent of the Biden administration’s engagement, then, represents a strategic calculation about the value of the alliance in the Indo-Pacific.

Figure 1.3. High-level engagements with Indo-Pacific countries in the first 18 months of the three administrations

All minilateral meetings are counted as discrete engagements for each participating country. Each meeting is counted as one engagement for the purposes of the total. Inclusive multilateral meetings (e.g., ASEAN summits) are not counted for any participating country.13

| Country | Total engagements | ||

| Obama | Trump | Biden | |

| Australia | 17 | 14 | 32 |

| Bangladesh | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Brunei | 6 | 0 | 3 |

| Cambodia | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| China | 17 | 24 | 14 |

| Federated States of Micronesia | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Fiji | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| India | 6 | 17 | 31 |

| Indonesia | 9 | 9 | 11 |

| Japan | 26 | 55 | 52 |

| Malaysia | 7 | 7 | 6 |

| Myanmar | 5 | 2 | 2 |

| New Zealand | 7 | 4 | 5 |

| North Korea | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Palau | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Philippines | 6 | 11 | 12 |

| Singapore | 8 | 16 | 9 |

| South Korea | 11 | 52 | 34 |

| Sri Lanka | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Thailand | 1 | 6 | 7 |

| Vietnam | 6 | 10 | 5 |

| Total | 132 | 229 | 233 |

It must be acknowledged that such relationships with resolute democratic allies are more easily maintained. Anxieties about US commitment are less prominent in countries like Australia and Japan, where steadfast alliances and material cooperation with the United States is well-established. These dialogue opportunities complement a host of substantive changes in the character of the US-Australia alliance since the Biden administration began, including the revitalisation of the Quad, AUKUS, new Force Posture Initiatives, and cooperative efforts in Ukraine.

The Biden administration did not, however, significantly or ubiquitously expand US engagement with Southeast Asian countries. The administration increased the number of meetings held with Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand but the frequency of high-level meetings with officials from Vietnam, Singapore and Malaysia declined. With the announcement of AUKUS and the development of the Quad alarming some in the region, the onus on the United States to engage in robust dialogue with Southeast Asian partners is higher than ever. Though diplomacy in this sub-region is something the US traditionally expects allies like Australia to conduct on its behalf, the Solomon Islands case proved that the US cannot depend on its partners alone for influence. Moreover, both President Trump and President Obama visited a Southeast Asian country in their first year in office. It is among these diplomatically challenging countries that high-level travel – demonstrating the extent of both US commitment and capacity – stands to be most impactful.

2. Travel to and from the Biden administration’s “priority theater”

Travelling to visit a partner for a face-to-face meeting enables US leaders to develop friendships, discuss sensitive issues, and more directly shape public opinion overseas. This section considers 124 foreign visits and 53 hosted visits held by these officials in the first 18 months of the Biden administration. The data makes clear that Europe, rather than the Indo-Pacific, remains the United States' centre of diplomatic gravity.

Definitions of key terms

'Foreign visit' refers to the presence of an official in an overseas country for any period of time or purpose, barring for refuelling. Occasions where two officials travelled to a country for one event or engagement are counted as two discrete engagements, in recognition of the significance of simultaneously inspiring the attention of two influential foreign policy decisionmakers with differential remits.

'Hosted visit' refers to instances where one of the officials of interest hosted a counterpart or counterparts from an overseas country for a bilateral or multilateral meeting in the United States.

Diplomatic travel under the Biden administration

From the administration’s inauguration on 20 January 2021 to 20 July 2022, President Biden, Secretary Blinken and Secretary Austin conducted 124 foreign visits altogether. Despite the administration’s repeated claim that the Indo-Pacific is its “priority theater,”14 officials’ time in the region was dwarfed by their travels to Europe. Though visits to Indo-Pacific partners were an early priority, they have increasingly been far outstripped by visits to European countries, in some part due to the first land war on the continent in decades.

Figure 2.1. Distribution of high-level foreign visits in the Biden administration’s first 18 months in office

| Most visited countries | High-level visits by region | |||

| Country | Visits | Region | Visits | |

| Belgium | 15 | Europe | 70 | |

| Germany | 9 | Middle East and North Africa | 23 | |

| United Kingdom | 7 | Indo-Pacific | 22 | |

| Israel | 5 | Other | 9 | |

| Japan | 5 | |||

| Poland | 5 | |||

| Ukraine | 5 | |||

| France | 4 | |||

| Palestinian Authority | 4 | |||

| South Korea | 4 | |||

| Italy | 3 | |||

| Switzerland | 3 | |||

| Vatican City | 3 | |||

Following the precedent set by Secretary Mattis in the Trump administration, Japan and South Korea were the first countries in the world to be visited by a Biden administration Cabinet-level official.15 These countries remain among the administration’s most visited countries and are the recipients of 40 per cent of high-level officials’ total visits in the Indo-Pacific.

Yet, over 18 months, Biden administration officials travelled to Europe more than three times more frequently than to the Indo-Pacific. Moreover, high-level administration presence in the Indo-Pacific was narrowly exceeded by administration travel to the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). Visits to Indo-Pacific countries represented only 18 per cent of combined high-level visits. Indo-Pacific travel is challenging for any administration. It is a considerable distance from the United States – often demanding 24 hours or more of flight times from Washington DC, compared to Western Europe only requiring 5-hour flights.

Europe, rather than the Indo-Pacific, remains the United States' centre of diplomatic gravity.

Border restrictions and personal health risks during the COVID-19 pandemic also foreclosed travel to some Indo-Pacific allies.16 In the very early months of the Biden administration, it was said that President Biden limited his diplomats’ travel to “matters of war and peace.”17 Border closures in several key Indo-Pacific countries endured long past those restrictions in many European US allies.18 For example, for most of the first 18 months of the Biden administration’s tenure, Australia did not allow foreign visitors. As recently as April 2022, a delegation from the Senate Foreign Relations Committee couldn’t travel to New Zealand or Indonesia due to COVID-19 restrictions.

Nevertheless, the extent of senior officials’ concentration on Europe is significant. This tendency to revert to Europe was especially strong at the presidential level; of the 15 foreign visits President Biden undertook in his first 18 months in office, 10 were to Europe. As Deputy National Security Advisor Amanda Sloat summarised, “the President is certainly a true transatlanticist. Having worked on all these European issues for decades…it’s no surprise that the President’s first trip [was] to Europe.”19 Following a period of NATO scepticism under President Trump, President Biden’s travel has been an important mechanism to restore trust in relationships in Europe.20

Figure 2.2. Regional distribution of combined high-level and presidential travel during the Biden administration’s first 18 months in office

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine inspired a flurry of administration travel to coordinate with NATO partners. Secretary Austin, for example, travelled to Belgium repeatedly to convene the Ukraine Defense Contact Group, and Blinken and Austin made an unannounced visit to Ukraine itself.21 However, the Biden administration’s attraction to Europe predated the Ukraine crisis. In 2021, prior to the invasion, 52 per cent of high-level administration visits were to European countries. For comparison, only 35 per cent of such travel was dedicated to Europe in the first year of both the Obama and Trump presidencies.

In some regards, dialogue opportunities with European allies came at the expense of regular Indo-Pacific diplomacy. President Biden’s special summit with ASEAN leaders, initially scheduled for March 2022, was postponed to better focus on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.22 For the same reason, President Biden also rescheduled a trip to Japan planned for April 2022.23 Regardless, the recently released National Defense Strategy insists that US “commitments to allies and partners in the Indo-Pacific are steadfast.”24 Secretary Blinken’s visit to Australia and Fiji in February 2022 – mere days after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine began – sought to demonstrate that the administration could “walk and chew gum”25 in both regions.

Despite its difficulties, a consistent presence in the Indo-Pacific is a strategic necessity for any administration, particularly one whose National Security Strategy prioritises efforts to “maintain an enduring competitive edge over the PRC.”26 Lowy Institute data attests that, over the last decade, Chinese presidential travel has appreciably outstripped the United States executive branch's outreach throughout Asia and the Pacific.27 Furthermore, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s travels throughout the Indo-Pacific exceed those of Secretary Blinken.28 With that said, President Xi Jinping did not leave China between 2018 and September 2022, increasing the strategic significance of President Biden’s May travel to Northeast Asia.

Analysis of 51 available readouts from diplomatic meetings reveals a similar diplomatic approach in different regions. Figure 2.3 illustrates a shared emphasis on the US commitment to security guarantees, multilateralism, and answering non-traditional threats. At the same time, there are regional idiosyncrasies. Trade features prominently in meetings with European partners. The Biden administration’s reticence around Indo-Pacific trade agreements is demonstrated in its absence from diplomatic meetings, though it should be noted this dataset does not include the September 2022 Indo-Pacific Economic Framework ministerial meetings.

Figure 2.3. Content of high-level engagements in the Indo-Pacific vs. Europe under the Biden administration in its first 18 months

Cleaned datasets29 of word use were assembled from the 15 available readouts of meetings held by the officials of interest in the Indo-Pacific and the 17 available from engagements in Europe.

| Readouts from Biden administration engagements in the Indo-Pacific | Readouts from Biden administration engagements in Europe | |||||

| Rank | Word | Frequency | Rank | Word | Frequency | |

| 1 | cooperation | 26 | 1 | Ukraine | 42 | |

| 2 | security | 20 | 2 | defense | 18 | |

| 3 | commitment | 17 | 3 | security | 17 | |

| 4 | defense | 16 | 3 | commitment | 17 | |

| 5 | alliance | 14 | 5 | united | 16 | |

| 6 | bilateral | 12 | 6 | Russia | 15 | |

| 6 | Indo-Pacific | 12 | 7 | efforts | 13 | |

| 6 | strengthen | 12 | 7 | support | 13 | |

| 6 | united | 12 | 9 | assistance | 11 | |

| 10 | climate | 9 | 9 | alliance | 11 | |

| 10 | COVID-19 | 9 | 11 | provide | 10 | |

| 10 | training | 9 | 12 | partners | 9 | |

| 13 | democracy | 8 | 13 | humanitarian | 8 | |

| 13 | exercise | 8 | 13 | military | 8 | |

| 13 | future | 8 | 13 | diplomacy | 8 | |

| 13 | support | 8 | 16 | aggression | 7 | |

| 17 | challenges | 7 | 16 | NATO | 7 | |

| 17 | DPRK | 7 | 18 | against | 6 | |

| 17 | peace | 7 | 18 | climate | 6 | |

| 17 | prosperity | 7 | 18 | cooperation | 6 | |

| 17 | strong | 7 | 18 | forces | 6 | |

| 22 | crisis | 6 | 22 | challenges | 5 | |

| 22 | forces | 6 | 22 | global | 5 | |

| 22 | partnership | 6 | 22 | Iran | 5 | |

| 25 | change | 5 | 22 | unprovoked | 5 | |

| 25 | increase | 5 | 22 | increase | 5 | |

| 25 | priority | 5 | 22 | strong | 5 | |

| 25 | promote | 5 | 22 | service | 5 | |

| 25 | strategic | 5 | 22 | weapons | 5 | |

| 30 | aircraft | 4 | 22 | strategy | 5 | |

| 30 | cyber | 4 | 22 | economy | 5 | |

| 30 | efforts | 4 | 32 | bilateral | 4 | |

| 30 | establishment | 4 | 32 | impose | 4 | |

| 30 | exchange | 4 | 32 | more | 4 | |

| 30 | free | 4 | 32 | presence | 4 | |

| 30 | open | 4 | 32 | strengthen | 4 | |

| 30 | opportunities | 4 | 32 | trade | 4 | |

| 30 | order | 4 | 32 | transatlantic | 4 | |

| 30 | relationship | 4 | 32 | values | 4 | |

| 30 | threat | 4 | 32 | war | 4 | |

| 30 | treaty | 4 | 32 | Zelenskyy | 4 | |

| 42 | ASEAN | 3 | 32 | contributions | 4 | |

| 42 | China | 3 | 32 | relationship | 4 | |

| 42 | combat | 3 | 32 | return | 4 | |

| 42 | cornerstone | 3 | 32 | worldwide | 4 | |

| 42 | develop | 3 | 32 | territory | 4 | |

| 42 | economy | 3 | 47 | build | 3 | |

| 42 | health | 3 | 47 | coordination | 3 | |

| 42 | issues | 3 | 47 | costs | 3 | |

| 42 | linchpin | 3 | 47 | COVID-19 | 3 | |

| 42 | military | 3 | 47 | development | 3 | |

| 42 | multilateral | 3 | 47 | dialogue | 3 | |

| 42 | peninsula | 3 | 47 | education | 3 | |

| 42 | recovery | 3 | 47 | help | 3 | |

| 42 | rules | 3 | 47 | importance | 3 | |

| 42 | sea | 3 | 47 | leadership | 3 | |

| 42 | space | 3 | 47 | review | 3 | |

| 42 | stability | 3 | 47 | science | 3 | |

| 42 | trilateral | 3 | 47 | significant | 3 | |

| 42 | vital | 3 | 47 | situation | 3 | |

| 47 | together | 3 | ||||

| 47 | unjustified | 3 | ||||

| 47 | unwavering | 3 | ||||

| 47 | training | 3 | ||||

| 47 | protect | 3 | ||||

| 47 | vaccines | 3 | ||||

| 47 | Afghanistan | 3 | ||||

| 47 | capabilities | 3 | ||||

| 47 | crisis | 3 | ||||

| 47 | escalate | 3 | ||||

| 47 | power | 3 | ||||

| 47 | threat | 3 | ||||

| 47 | unique | 3 | ||||

| 47 | free | 3 | ||||

Consistent with the US “hub and spoke” model of alliances in the Indo-Pacific and the absence of a regional security body like NATO, there is a stronger emphasis on extending bilateral cooperation during Indo-Pacific engagements. Sixteen (73 per cent) of the administration’s 22 high-level foreign visits to Indo-Pacific countries were singularly bilateral in orientation. In contrast, less than 50 per cent of high-level visits to European countries were for bilateral meetings alone.

Indo-Pacific visitors to the United States under the Biden administration

President Biden hosted 30 meetings with foreign heads of state in his first 18 months in office, including four multilateral summits. Seven of these (27 per cent) meetings were with Indo-Pacific officials. Though this is a small number relative to other regions, each of these meetings was substantively significant in elevating regional partnerships – most notably, with the regional democratic allies, individually and together through the Quad.

Altogether, President Biden, Secretary Blinken and Secretary Austin hosted 30 meetings with counterparts from the Indo-Pacific in the United States before 20 July 2022. Again, the Biden administration prioritised its regional democratic allies. The first head of state to visit the Biden White House was Japanese Prime Minister Suga Yoshihide on 16 April 2021. Due to border closures in Australia and India, their officials’ high-level meetings with the administration were mostly held in the United States. Subsequently, Australian officials were hosted by the administration in Washington on five separate occasions.

Figure 2.4. Visits hosted and received by Indo-Pacific countries under the Biden administration

Minilateral meetings are counted for each participating country. If two counterparts were hosted, each by a different US official (i.e., for a 2+2 ministerial), they were counted as two engagements for the country, in accordance with how outbound travel is counted.

3. Indo-Pacific relations since the “rebalance”

Expanding engagement with Asia has been a priority for US policymakers since the Obama administration announced its “rebalance” to the region in the 2012 Defense Strategic Guidance.30 President Obama would go on to make more trips to Southeast Asia than any US president before him.31 Though President Trump rarely travelled abroad, he dispatched his cabinet secretaries to the region often and was the first US president to set foot in North Korea. The Biden administration entered office grappling with a problematic diplomatic legacy in the Indo-Pacific, with many ambassadorial postings left unfilled and many partners' trust damaged by President Trump’s rhetoric.32 As the Biden administration increasingly turns towards its Indo-Pacific partners in a deteriorating strategic environment, it is imperative to revisit the diplomatic successes and failures in the region of former White House occupants.

Travel trends from Obama to Biden

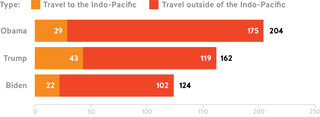

With the global pandemic obstructing diplomatic travel, President Biden and his secretaries conducted 124 visits to foreign countries over the administration’s first 18 months, compared with 162 over the same duration under the Trump presidency, and 204 under President Obama. President Obama and Secretary John Kerry were more frequent travellers than their successors. Notably, this brief’s travel catalogue confirms that Secretary Mattis of the Trump administration had the most extensive itinerary of any Defense Secretary.

Figure 3.1. The distribution of high-level travel in an administration’s first 18 months

Much of the diplomatic travel under any administration is determined by annual summits and ministerial consultations. Visits to the NATO and EU headquarters in Belgium, for example, are necessary to maintain those alliances under any presidency. Owing to such long-standing obligations, the distribution of high-level travel has evolved, for the most part, slowly over time. Early high-level travel to the Middle East has declined since the Obama administration, as the priorities of US foreign policy have evolved. Japan and South Korea increasingly appear among the most visited countries by senior US officials.

Figure 3.2. Most visited countries at a high level in an administration’s first 18 months

| Indo-Pacific | ||||||||||

| Europe | ||||||||||

| Middle East and North Africa | ||||||||||

| Obama administration | Trump administration | Biden administration | ||||||||

| Rank | Country | Visits | Rank | Country | Visits | Rank | Country | Visits | ||

| 1 | France | 14 | 1 | Belgium | 13 | 1 | Belgium | 14 | ||

| 1 | Israel | 14 | 2 | United Kingdom | 8 | 2 | Germany | 9 | ||

| 1 | Jordan | 14 | 3 | South Korea | 7 | 3 | United Kingdom | 7 | ||

| 4 | Palestinian Authority | 12 | 4 | Saudi Arabia | 6 | 4 | Japan | 5 | ||

| 5 | United Kingdom | 11 | 4 | Germany | 6 | 4 | Israel | 5 | ||

| 6 | Belgium | 10 | 4 | Italy | 6 | 4 | Poland | 5 | ||

| 6 | Saudi Arabia | 10 | 4 | Japan | 6 | 4 | Ukraine | 5 | ||

| 8 | Afghanistan | 7 | 4 | China | 6 | 8 | South Korea | 4 | ||

| 9 | Germany | 6 | 9 | Qatar | 5 | 8 | France | 4 | ||

| 9 | Italy | 6 | 9 | Canada | 5 | 8 | Palestinian Authority | 4 | ||

Diplomatic itineraries do change in response to presidents’ preferences and emerging strategic challenges. Struggling against COVID-19 border closures and competing priorities elsewhere, President Biden and Secretaries Blinken and Austin scheduled only 22 visits to the Indo-Pacific in their first 18 months in office, whereas the Obama administration held 29 and the Trump administration held 43 in the same time period. That being said, as a proportion of their travel, Secretary Blinken and Secretary Austin were slightly more focused on Indo-Pacific countries than their Obama administration predecessors.

Figure 3.3. High-level foreign visits to Indo-Pacific countries in an administration’s first 18 months

Despite the stated priorities of its Indo-Pacific and National Security Strategies, the Biden administration has undone some of the Trump administration’s efforts to refocus US diplomacy on the Indo-Pacific. The total number of visits to the Indo-Pacific, as well as the proportion of visits designated to Indo-Pacific countries versus elsewhere, are lower under the Biden administration than they were under the Trump administration. Twenty-seven per cent of high-level foreign visits conducted during the first 18 months of the Trump administration were to the Indo-Pacific versus only 18 per cent of Biden officials’ total diplomatic visits. Some of this discrepancy can be justified by the restrictions on regional travel due to COVID-19, as discussed previously.

In contrast, the Biden administration was uniquely present in Europe. Almost 60 per cent of high-level foreign visits held during the Biden administration’s first 18 months in office were to European countries, compared with just 35 per cent of Obama and Trump administration high-level travel over an equivalent period. As already discussed, this trend cannot be wholly explained by the Ukraine crisis, nor is it a result of a renewed commitment to summitry; in the first year of all three presidencies, the G20 and G7 presidencies resided with a European country.

President Biden’s delayed arrival for introductions in the Indo-Pacific is especially notable when compared with his predecessors. President Biden took 16 months to arrive for face-to-face meetings in the region, and only visited two countries. In contrast, in November 2009, 10 months into his first term, President Obama took a four-country tour of Asia. Similarly, in November 2017, President Trump travelled to five Indo-Pacific countries on his longest trip at that point as president and the longest trip by any president to Asia.33 Both presidents’ itineraries included a visit to China and a Southeast Asian country, though in both instances that stop was for an APEC Leaders’ Meeting, which was held remotely during the Biden administration.34

Comparing 354 meeting readouts over three administrations reveals considerable stability in US engagement with their Indo-Pacific partners. Where Figure 2.4 contrasts one administration’s engagement in two regions, Figure 3.4 compares Indo-Pacific engagement under two administrations. The official rhetoric is consistent around China, ASEAN-centrality, and the US commitment to regional stability at large, even as leaders’ preferences and priorities evolved. The declining centrality of North Korea to Biden administration meetings, and the increased salience of COVID-19, climate change and Taiwan, are evidence of the evolving regional threat environment.

Figure 3.4. Content of available readouts from high-level engagements with the Indo-Pacific in the Trump administration and the Biden administration

Raw datasets were assembled from the 182 and 172 available readouts of meetings held by the officials of interest with Indo-Pacific counterparts over the period. Word frequency was calculated using Kennis counter.35

| Themes from Trump administration engagements with the Indo-Pacific | Themes from Biden administration engagements with the Indo-Pacific | |||||

| Rank | Word | Frequency | Rank | Word | Frequency | |

| 1 | DPRK | 225 | 1 | security | 161 | |

| 2 | security | 161 | 2 | Indo-Pacific | 137 | |

| 3 | united | 155 | 3 | cooperation | 134 | |

| 4 | defense | 154 | 4 | alliance | 128 | |

| 5 | ROK | 134 | 5 | strength | 105 | |

| 6 | commitment | 125 | 6 | commitment | 99 | |

| 7 | cooperation | 122 | 7 | partnership | 94 | |

| 8 | threats | 78 | 8 | defense | 91 | |

| 9 | alliance | 63 | 9 | sharing | 82 | |

| 10 | efforts | 49 | 10 | leadership | 79 | |

| 11 | support | 47 | 11 | united | 78 | |

| 12 | international | 46 | 12 | peace | 71 | |

| 13 | strong | 44 | 13 | support | 70 | |

| 14 | bilateral | 43 | 14 | effort | 67 | |

| 14 | issues | 43 | 15 | prosperity | 63 | |

| 14 | peace | 43 | 16 | ROK | 61 | |

| 17 | China | 42 | 17 | freedom | 59 | |

| 18 | Indo-Pacific | 40 | 17 | state | 59 | |

| 18 | partners | 40 | 19 | COVID-19 | 55 | |

| 20 | denuclearisation | 38 | 20 | bilateral | 53 | |

| 21 | global | 37 | 21 | DPRK | 52 | |

| 22 | pressure | 34 | 22 | challenge | 51 | |

| 22 | stability | 34 | 23 | open | 50 | |

| 24 | ballistic missile | 30 | 24 | China | 49 | |

| 24 | coordination | 30 | 25 | democracy | 48 | |

| 24 | maritime | 30 | 26 | climate | 47 | |

| 27 | ASEAN | 29 | 26 | economic | 47 | |

| 27 | economic | 29 | 28 | Ukraine | 43 | |

| 27 | forces | 29 | 29 | issues | 41 | |

| 27 | maintain | 29 | 30 | opportunity | 38 | |

| 27 | military | 29 | 31 | Burma | 36 | |

| 27 | mutual | 29 | 32 | ASEAN | 34 | |

| 33 | free | 28 | 32 | international | 34 | |

| 33 | interests | 28 | 34 | rule | 33 | |

| 33 | nuclear | 28 | 34 | sea | 33 | |

| 33 | summit | 28 | 36 | response | 32 | |

| 37 | launch | 27 | 36 | crisis | 32 | |

| 37 | territory | 27 | 36 | response | 32 | |

| 39 | ISIS | 26 | 36 | strategy | 32 | |

| 40 | strategic | 25 | 40 | military | 31 | |

| 40 | trade | 25 | 41 | meetings | 29 | |

| 42 | challenges | 24 | 41 | values | 29 | |

| 42 | open | 24 | 43 | forward | 28 | |

| 42 | terrorism | 24 | 43 | Korean peninsula | 28 | |

| 45 | missile | 23 | 45 | interests | 27 | |

| 46 | joint | 22 | 45 | launch | 27 | |

| 47 | law | 21 | 47 | trilateral | 26 | |

| 47 | rules | 21 | 48 | pandemic | 25 | |

| 49 | contribution | 20 | 48 | priority | 25 | |

| 49 | deterrence | 20 | 50 | change | 24 | |

| 49 | diplomatic | 20 | 50 | force | 24 | |

| 52 | provocation | 19 | 50 | relationship | 24 | |

| 52 | trilateral | 19 | 53 | mutual | 23 | |

| 54 | actions | 18 | 53 | country | 23 | |

| 55 | Korean peninsula | 17 | 55 | ballistic missile | 22 | |

| 55 | prosperity | 17 | 55 | Russia | 22 | |

| 55 | test | 17 | 57 | denuclearisation | 21 | |

| 58 | Kim Jong-Un | 16 | 57 | order | 21 | |

| 58 | order | 16 | 59 | action | 20 | |

| 58 | verifiable | 16 | 59 | coordination | 20 | |

| 61 | build | 15 | 59 | law | 20 | |

| 61 | irreversible | 15 | 62 | aggression | 19 | |

| 61 | sea | 15 | 62 | rights | 19 | |

| 61 | weapons | 15 | 62 | human | 19 | |

| 65 | progress | 14 | 62 | nation | 19 | |

| 65 | respect | 14 | 66 | ironclad | 18 | |

| 67 | counter | 13 | 66 | Quad | 18 | |

| 67 | implementation | 13 | 68 | deterrence | 17 | |

| 67 | promote | 13 | 68 | providing | 17 | |

| 70 | Asia-Pacific | 12 | 70 | assistance | 16 | |

| 70 | central | 12 | 71 | environment | 15 | |

| 70 | concern | 12 | 71 | progress | 15 | |

| 70 | counterterrorism | 12 | 71 | resolution | 15 | |

| 70 | long | 12 | 71 | summit | 15 | |

| 70 | opportunities | 12 | 71 | treaty | 15 | |

| 70 | ships | 12 | 71 | appreciation | 15 | |

| 70 | training | 12 | 77 | Afghanistan | 14 | |

| 70 | violence | 12 | 77 | maritime | 14 | |

| 79 | democracy | 11 | 77 | threat | 14 | |

| 79 | environment | 11 | 80 | anniversary | 13 | |

| 79 | freedom | 11 | 80 | cornerstone | 13 | |

| 79 | goals | 11 | 80 | engagement | 13 | |

| 79 | leadership | 11 | 80 | health | 13 | |

| 79 | sanctions | 11 | 80 | multilateral | 13 | |

| 85 | attack | 10 | 80 | Pacific | 13 | |

| 85 | fight | 10 | 80 | Taiwan | 13 | |

| 85 | humanitarian | 10 | 80 | critical | 13 | |

| 85 | Olympics | 10 | 88 | coup | 12 | |

| 85 | regime | 10 | 88 | visit | 12 | |

| 90 | Xi Jinping | 9 | 88 | war | 12 | |

| 90 | enforcement | 9 | 91 | development | 11 | |

| 90 | escalate | 9 | 91 | linchpin | 11 | |

| 90 | extremism | 9 | 91 | posture | 11 | |

| 90 | fair | 9 | 91 | resolving | 11 | |

| 90 | force | 9 | 91 | responsibility | 11 | |

| 90 | intercontinental | 9 | 91 | violation | 11 | |

| 90 | operations | 9 | 91 | training | 11 | |

| 90 | resolve | 9 | 91 | success | 11 | |

| 90 | sharing | 9 | 99 | capability | 10 | |

| 100 | armed | 8 | 99 | centrality | 10 | |

| 100 | assistance | 8 | 99 | collaboration | 10 | |

| 100 | carrier | 8 | 99 | future | 10 | |

| 100 | destabilise | 8 | 99 | policy | 10 | |

| 100 | information | 8 | 99 | protect | 10 | |

| 100 | overflight | 8 | 99 | sovereignty | 10 | |

| 100 | successful | 8 | 99 | exercise | 10 | |

| 99 | fight | 10 | ||||

Visitors from the Indo-Pacific across three administrations

The Trump administration hosted more meetings with senior officials from the Indo-Pacific in its first 18 months than either the Obama or Biden administrations. This is especially the case at the leaders’ level, where President Trump more than doubled the number of meetings President Biden hosted with Indo-Pacific counterparts. President Trump’s eagerness to host meetings is not necessarily indicative of purposeful diplomatic prioritisation. Some analysts have commented that President Trump’s highly personalised approach to decision-making motivated officials from the region to seek opportunities to befriend and flatter the president.36 In his first year in office, President Trump lauded his personal relationships with regional heads of state, including President Rodrigo Duterte of the Philippines, Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzo and Chinese President Xi Jinping.37

In the face of COVID-19 restrictions, President Biden exceeded the standard set by President Obama for hosting summits or meetings with regional officials. President Biden was the only president of the three to offer his first invitation to the White House to an Indo-Pacific head of state. Under the Trump administration, Prime Minister Abe was third after British Prime Minister Theresa May and King Abdullah II of Jordan. The Japanese Prime Minister was the third leader to visit the Obama White House in the President’s second term, and the second visitor in his first term.

Figure 3.5. Hosted officials from a given Indo-Pacific country by administration

Minilateral engagements have been counted as discrete engagements for each participating country. Totals provided are therefore not cumulative.

| Country | Number of officials hosted by administration at a high level | ||

| Obama | Trump | Biden | |

| Australia | 4 | 4 | 6 |

| Bangladesh | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| China | 2 | 4 | 1 |

| India | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| Indonesia | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Japan | 3 | 7 | 5 |

| Malaysia | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Myanmar | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| New Zealand | 4 | 0 | 2 |

| North Korea | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Palau | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Philippines | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Singapore | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| South Korea | 4 | 7 | 3 |

| Thailand | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Vietnam | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| Total | 28 | 43 | 30 |

President Biden and his appointees played a uniquely prominent convening role in regional multilateral meetings. The officials of interest hosted four Indo-Pacific summits in the United States in their first 18 months, whereas the Trump administration held one and the Obama administration held two. Two of the Biden administration’s meetings were with ASEAN, compensating in some respect for their shortage of visits to ASEAN countries.

4. Summitry and strategic engagement

Indo-Pacific attitudes towards US engagement

In 2021, the Lowy Power Index reported large gains in US diplomatic influence (+15.5 from the previous year) despite low rates of travel under the Biden administration.38 Certainly, secretarial travel alone cannot sustain US regional influence without substantive commitments. At the end of the Obama administration, USSC polling found that 48 per cent of Japanese respondents nominated the United States as the most influential country in Asia. At the end of President Trump’s first year, this percentage fell to just 14 per cent.39

However, stable diplomatic engagement with a country is correlated with greater public trust in the United States. The ISEAS State of Southeast Asia Report revealed that most Southeast Asians positively acknowledge President Biden’s efforts to restore global governance, in accordance with his administration’s strong showing at international summits.40 However, it finds that trust in the administration varies country-to-country. In Pew Research Centre Spring 2022 polling, Japan and South Korea stand out in Asia for the extent of their “confidence in Joe Biden to do the right thing regarding world affairs.”41 Opinions are more divided in countries like Malaysia and Singapore that have received more intermittent high-level attention.

Altogether, polling data suggests that diplomatic predictability, rather than frequency, matters most in developing trust in US presence in Asia. In 2018, the Lowy Institute found that 55 per cent of Australians trusted the United States to act responsibly in the world. In 2022, 65 per cent of Australians trust the United States to act responsibly in the world, despite President Biden’s less extensive travel and virtual communication with regional partners.

Regular cooperation with limited and inclusive regional groupings is a core component of the US diplomatic routine in the Indo-Pacific. As a previous USSC report argued,42 comprehensive engagement with multilateral institutions provides the United States with access, an amplified voice and the opportunity to present itself as a positive, committed player in the region.

Indo-Pacific institutions and US diplomacy

US cooperation with different groupings in the Indo-Pacific has fluctuated over time. The Obama administration, advancing a rebalance to Asia, elevated and reinforced ASEAN to an importance “not seen since the end of the Vietnam war.”43 The first-ever ASEAN-US Summit was held in October 2013, though President Obama himself was unable to attend.44 Though somewhat hostile to multilateral efforts, the Trump administration was responsible for resuscitating the Quad at the ministerial level. By consistently attending annual summits at the right level, conducting sidelines outreach, and elevating advantageous minilateral groupings, the Biden administration has reintroduced stability to US regional multilateralism.

Figure 4.1. Total high-level administration engagements with Indo-Pacific fora in 18 months45

| Organisation | Total engagements | ||

| Obama | Trump | Biden | |

| APEC | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| ASEAN | 5 | 8 | 8 |

| East Asia Summit | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| US-Australia-Japan | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| US-Japan-South Korea | 3 | 5 | 6 |

| Quad | - | - | 6 |

| Friends of the Mekong | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| AUKUS | - | - | 3 |

President Biden and his appointees embraced both large-scale multilateral coordination and the minilateralism preferred by the Trump administration. The Biden administration’s enthusiasm for small, values-driven coalitions like the Quad and AUKUS has not detracted from its engagement with ASEAN, APEC and the East Asia Summit. President Biden and his appointees have redressed engagement with ASEAN to its original levels, which waned in the later phases of the Trump administration. Importantly, President Biden appointed a US special envoy to ASEAN after five years of the post being left vacant.

US-ASEAN engagement under President Biden has faced some impediments. As previously mentioned, President Biden postponed a meeting intended to demonstrate “the United States’ enduring commitment” to the group from the end of March to May.46 Regardless of the administration’s near-perfect attendance record at the most significant annual summits, Jonathan Stromseth of the Brookings Institute summarised that the substance of US-ASEAN relations still faces “a convergence of unrealistic expectations, with both sides wanting what the other is incapable of delivering.”47 Nonetheless, if this first test of US commitment to cooperation is their willingness to show up, the Biden administration has performed admirably.

Ten years of summits in the Indo-Pacific

The annual meetings of APEC, ASEAN, the East Asia Summit and the US-Mekong Partnership form the bedrock of US regional multilateralism. Missing these summits has proven to have significant, if short-term, implications for perceptions of the United States. As Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong stated after President Obama missed the 2013 summit meetings, “we prefer a US president who is able to travel to fulfill his international duties to one who is preoccupied with domestic issues."48

In their first 18 months in office, President Biden, Secretary Blinken and Secretary Austin have missed no major annual meeting. Just as the administration sustained a high-profile and regularly remarked-upon presence at key summits in Europe, including the G7, NATO and EU meetings, these key officials were careful to attend summits with Indo-Pacific groupings. The administration has also dispatched representatives of various levels to attend an array of additional meetings, including India’s Raisina Dialogue and the Pacific Islands Conference of Leaders. Taken together, the Biden administration has a better record for regional summit attendance than either of its predecessors.

Figure 4.2. Summit attendance in the Indo-Pacific from 2013 to the present 49

| Not attended | |||||||||||

| Attended, but below requisite level | |||||||||||

| Attended | |||||||||||

| Not held/to be held | |||||||||||

| Group | Summit | Obama | Trump | Biden | |||||||

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | ||

| APEC | Leaders' | ||||||||||

| Foreign ministers' | |||||||||||

| ASEAN | Leaders' | ||||||||||

| Foreign ministers' | |||||||||||

| Defense ministers' | |||||||||||

| East Asia Summit | Leaders' | ||||||||||

| Foreign ministers' | |||||||||||

| Mekong | Foreign ministers' | ||||||||||

| Shangri-La | Defense ministers' | ||||||||||

President Obama and his senior appointees made every effort to attend regional meetings. However, a government shutdown in 2013 coincided with the Indo-Pacific summit season, rendering President Obama unavailable for the duration. President Trump became notorious for his disinterest in multilateralism. After his first year in office, President Trump continually refrained from attending the US-ASEAN Summit and the East Asia Summits, raising the ire of regional commentators.50

Meetings on the margins

Inclusive summit meetings provide a low-cost opportunity to meet with other visiting delegations. The annual Shangri-La Dialogue, which convenes Southeast Asian and regional defence officials in Singapore, consistently has the highest yield for US sidelines diplomacy of any international meeting.

President Biden held more sidelines meetings with Indo-Pacific officials in his first 18 months in office than either of his predecessors.

There are repercussions for failing to undertake sidelines diplomacy. As Susannah Patton commented after the May 2022 US-ASEAN Special Summit, where President Biden did not schedule any sidelines engagement, “a lack of bilateral meetings…clearly rankled some and was especially notable given that Biden has not yet established rapport with many of his counterparts in the region.”51 This failure to wholly satisfy regional expectations for engagement amplified regional criticisms about the tangible promises made by the administration at the summit.52

Recognising that COVID-19 limited opportunities for sidelines meetings, the Biden administration exceeded its predecessors’ records for such engagement over far fewer multilateral meetings. President Biden held more sideline meetings with Indo-Pacific officials in his first 18 months in office than either of his predecessors. Public records bear testament to only two sidelines meetings between President Obama and Indo-Pacific heads of state over the period, where President Trump held 12 and President Biden held 13.

Figure 4.3. High-level sidelines meetings held in an administration’s first 18 months in office

Minilateral meetings are counted for each participating country. Totals are therefore not cumulative.

| Country/organisation | Number of high level sidelines meetings | ||

| Obama | Trump | Biden | |

| ASEAN | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| Australia | 3 | 4 | 8 |

| Brunei | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Cambodia | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| China | 6 | 3 | 3 |

| India | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| Indonesia | 2 | 5 | 5 |

| Japan | 6 | 14 | 15 |

| Malaysia | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Myanmar | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| New Zealand | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Philippines | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Singapore | 2 | 5 | 2 |

| South Korea | 4 | 5 | 8 |

| Thailand | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Vietnam | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Total | 33 | 48 | 49 |

Though the Biden administration spent more time in Europe than is typical, it also increased the frequency of out-of-region sidelines engagement with Indo-Pacific partners. Over 18 months, senior Biden administration officials hosted 20 sidelines summits with Indo-Pacific leaders around European summits. Out-of-region meetings have delivered key outcomes in-region for the Indo-Pacific; a key chapter in the genesis of AUKUS, for example, was President Biden’s meeting with Prime Ministers Boris Johnson and Scott Morrison at the 2021 G7 in Cornwall. A sideline intervention at the Madrid NATO Summit revived the US-Japan-South Korea trilateral at the leaders’ level for the first time in almost five years. Through such meetings, the administration has reinforced Indo-Pacific partnerships while addressing urgent priorities elsewhere.

Figure 4.4. Sidelines summits with Indo-Pacific officials by convening region

| Region | Number of high level sidelines meetings | ||

| Obama | Trump | Biden | |

| Indo-Pacific | 26 | 26 | 20 |

| Europe | 4 | 10 | 19 |

| Middle East | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Hosted | 3 | 11 | 8 |

5. Commitment during COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic engulfed the domestic agenda of every country in the world, and both discouraged and, for a period, prevented international travel. To reasonably evaluate the Biden administration’s early Indo-Pacific engagement, it must be compared with that conducted by their Trump administration counterparts in 2020 under the same conditions.

Prioritisation via Zoom

The flourishing of remote forms of engagement is a predictable companion of COVID-19 conditions. Phone calls, digital meetings and virtual summits facilitated 132 high-level interactions with Indo-Pacific countries in the Biden administration’s first 18 months. For comparison, from 2017 to mid-2018, the Trump administration held 95 remote high-level meetings with counterparts from the region. Quad countries were the most regular participants in the Biden administration’s virtual discussions. Twenty-four remote bilateral meetings were held with Japan, 16 with India, and 15 with Australia, as well as two additional Quad minilateral digital summits.

Figure 5.1. High-level bilateral remote engagements by Indo-Pacific country in the Biden administration’s first 18 months in office

Total excludes 17 remote meetings held with minilateral and multilateral groupings. No official records were published of President Trump’s phone calls in 2020, preventing any comparative analysis of the pandemic era.

| Country | Number of virtual engagements |

| Australia | 15 |

| Bangladesh | 2 |

| Brunei | 2 |

| China | 11 |

| Federated States of Micronesia | 1 |

| India | 16 |

| Indonesia | 3 |

| Japan | 24 |

| Malaysia | 4 |

| Myanmar | 2 |

| New Zealand | 3 |

| Philippines | 8 |

| Singapore | 2 |

| South Korea | 17 |

| Sri Lanka | 1 |

| Thailand | 3 |

| Vietnam | 2 |

| Total | 115 |

As a foremost healthcare innovator with global responsibilities, the content of US diplomacy was shaped by the pandemic. COVID-19 appears in the readouts of 30 per cent of administration engagements with Quad counterparts, with whom it coordinated regional vaccination initiatives. The pandemic also prompted additional multilateral and necessarily global gatherings, led by President Biden.53

Yet it is notable that even facing such imperatives, President Biden himself did not make use of digital format for Indo-Pacific engagement as extensively as his predecessor. In his first 18 months in office, President Trump far exceeded the 24 calls President Biden made to Indo-Pacific counterparts over an equivalent period. President Trump held 16 bilateral phone calls with his Japanese and a further 17 with his South Korean counterparts alone. President Biden was a comparatively less dedicated correspondent. Below the leaders’ level, however, the Biden administration appointees proved slightly more active correspondents with Indo-Pacific partners. Secretary Blinken and Secretary Austin held a combined 69 remote engagements with Indo-Pacific partners in 2021, compared with Pompeo and Esper’s 60 in 2020.

It is perhaps most notable that President Biden, as far as public records attest, made no phone call to a single Southeast Asian leader for a bilateral conversation in his first year in office. RAND’s Derek Grossman remarked that “Southeast Asian interlocutors are in the dark as to why they cannot even secure a phone call.”54 In contrast, as early as April 2017, President Trump held phone calls with three Southeast Asian heads of state. This inattention fuelled regional countries’ feelings of insecurity around US commitment.

Masked miles travelled in the Indo-Pacific

Due to health risks and the domestic demands that accompanied the COVID-19 pandemic, neither President Trump in 2020 nor President Biden in 2021 visited the Indo-Pacific. Travel to the region remained stable, and necessarily limited, during the COVID-19 period. Both Trump and Biden administration officials conducted 12 visits to countries in the region over a one-year period. Secretary Pompeo’s regional travel in 2020 was more geographically diffuse, involving trips to the Maldives and Palau, but this is unsurprising; all administrations must make introductions to traditional allies a priority when entering office.

Trump administration officials conducted 84 foreign visits in 2020, whereas their Biden administration successors held only 68 in 2021. Thus, despite the rhetoric of bringing back diplomacy, President Biden and his appointees travelled less than their predecessors under comparable circumstances. It is especially significant then that the Biden administration surpassed the standard for high-level travel to Europe while presiding over a contraction in overall travel. High-level Biden administration officials made 36 visits to European countries in 2021, whereas their predecessors made 23 in 2020.

In 2021, the Biden administration hosted more officials at a high level overall, and more from the Indo-Pacific, than the previous administration. President Biden, Secretary Blinken and Secretary Austin hosted 19 hosted meetings with Indo-Pacific leaders in 2021. Only nine such meetings were held in 2020 while President Trump hosted no Indo-Pacific heads of state. It must be acknowledged, however, that mass vaccination loosened restrictions on face-to-face meetings in both the United States and the Indo-Pacific in 2021.

Strikingly, the most frequent source of high-level visitors to President Biden in 2021 was the Middle East and North Africa. Hosting regular visitors compensated somewhat for President Biden’s absence from the region in 2021. Prevailing COVID-19 conditions likely determined which foreign leaders were able and willing to travel; official visitors from the region were primarily from countries that either fared well under the pandemic, with low rates of infection (e.g., Jordan) or high rates of vaccination (e.g., Israel).

Summitry and the pandemic

The pandemic-induced transition to online events reduced the need for a regular in-region US presence. Undeniably a day spent on zoom from the comfort of a Washington office requires less pre-planning and commitment than a multi-day overseas visit.

However, President Trump continued to skip these Asian summits even when held online. Throughout the November 2020 Indo-Pacific summit season, National Security Advisor Robert O’Brien attended meetings in the place of President Trump. Though this non-attendance was President Trump’s third in as many years, his absenteeism accentuated concerns after the 2020 election for the United States’ ability to simultaneously wrestle with domestic and global challenges.55

Figure 5.2. Attendance at high-level Indo-Pacific summits, 2020-2021

| Not attended | |||

| Attended, but below requisite level | |||

| Attended | |||

| Not held/to be held | |||

| Group | Summit | Trump | Biden |

| 2020 | 2021 | ||

| APEC | Leaders' | Virtual | Virtual |

| Foreign ministers' | Virtual | Virtual | |

| ASEAN | Leaders' | Virtual | Virtual |

| Foreign ministers' | Virtual | Virtual | |

| Defense ministers' | Virtual | Virtual | |

| East Asia Summit | Leaders' | Virtual | Virtual |

| Foreign ministers' | Virtual | Virtual | |

| Mekong | Foreign ministers' | Virtual | Virtual |

| Shangri-La | Defense ministers' | Cancelled | Cancelled |

| Quad | Leaders' | Not held | Hosted |

| Foreign ministers' | Overseas | Virtual | |

| AUKUS | Leaders' | Not held | Virtual |

The cancellation or remote convening of multilateral summits limited opportunities for sidelines engagement throughout the pandemic. No major regional meetings were held in person in 2020 after the pandemic began, so, unsurprisingly, the Trump administration held few sidelines meetings in 2020.

In sum, the Biden administration can be commended for its showing at regional summits. As key meetings now transition back to in-person, in-region events, the test will be whether this record will continue.

Conclusions

Commentators at home and abroad are increasingly concerned with the return of US isolationism. Diplomatic travel and other forms of high-level dialogue are indispensable in reiterating to partners that the United States is here to stay.

In its first 18 months in office, the Biden administration made a considerable effort to “rise to [its] leadership charge on diplomacy” after a period of disturbance, as it committed to do in its Indo-Pacific Strategy.56 Audiences in the Indo-Pacific unsure of the United States’ capacity to return to global leadership and focus on Europe and Asia simultaneously should be reassured by officials’ meticulous summit attendance, sidelines diplomacy and remote engagement. Landmark meetings with ASEAN, the Pacific Islands nations and the Quad among others, augur well for the extent of the administration’s ambitions in the world of diplomacy.

On the metric of President Biden’s direct involvement, however, the focus on the Indo-Pacific appears less determined than the Trump administration. As evidenced by his sparse phone records, and by his delayed and subdued travel itinerary, President Biden has not been an involved dialogue partner in the region except to the United States’ already sympathetic democratic allies. The coming months will provide further opportunities to showcase his dedication to Indo-Pacific partners, as COVID-19 restrictions dissolve and the Ukraine crisis persists. To successfully compete for influence and ensure that ambitious initiatives like the Quad and AUKUS succeed, robust engagement with partners throughout the Indo-Pacific, including at the presidential level, will remain a strategic imperative.

The data used for this report can be downloaded as an Excel spreadsheet.