Economic ties between Australia and the United States have grown substantially over time as the two economies sought mutual benefit before forging new trade and investment relationships with the now dominant economies of the Indo-Pacific.

A curiosity of the Alliance, certainly since the Second World War, has been Australia and the United States’ shared political and security imperatives do not always align with their economic priorities. Broader diplomatic goals have often overpowered the competitive tension between the two economies yet, simultaneously, the economic importance of Australia and the United States to each other has multiplied.

The United States is Australia’s largest two-way investment partner and third-largest two-way trade partner, standing at A$80.8 billion in 2019-20.1 The two economies are among the fastest-growing in the developed world (before the COVID-19 pandemic) with both economies underpinned by the shared use of trade and investment as engines for growth.

The Australia-United States Free Trade Agreement (AUSFTA) is key; since its introduction in 2005, two-way investment has nearly tripled to A$1.8 trillion.2 The United States has long been Australia’s single most important source of foreign financing for domestic investment and economic growth.3

It wasn’t always so. Before the commencement of the ANZUS Treaty in 1952, Australia and the United States had marginal economic ties, despite the economic relationship dating as far back as 1793, when the American trading ship Hope delivered 7,500 gallons of rum to Sydney.4 To 1950, the United Kingdom dominated Australia’s trade with 44 per cent of two-way trade, while the United States represented just eight per cent.5

That disparity subsequently flipped significantly. In the fourth quarter of 2020, Australia exported US$1.5 billion of merchandise to the United States and only US$181 million to the United Kingdom, while importing US$2 billion from the United States and US$329 million from the United Kingdom.6 And in 2020, the United States had a 23 per cent share (on a total stock basis) of total foreign investment into Australia.7

Empire first

For the majority of the 20th century, the United Kingdom dominated trade with Australia due to the Imperial, or Commonwealth, Preference system of reciprocal tariff and trade agreements. The practice, dating back to the 17th century’s ‘old subsidy’ system, was a self-serving protection scheme for the British Empire benefitting the ‘Motherland’ with the first and best access to the resources from its colonies while enforcing their consumption of British goods and services. The practice received a boost around 1900 from UK Secretary of State for the Colonies, Joseph Richardson, who was spooked by the effects of protectionism by the United States and Germany.8

Yet Australia itself was split between protectionism versus free trade policies around Federation and in the early 1900s. While the state of Victoria used tariffs to promote industrial growth, New South Wales tended to avoid them. Emblematic of the split were the personalities aligned on either side pre-Federation in 1901: future prime ministers Edmund Barton and Alfred Deakin were members of the Protectionist Party, while the Free Trade Party counted Henry Parkes and Australia’s fourth prime minister George Reid among its members. Protectionism prevailed.9

After Federation, the preference system weakened as tariffs between former colonies were removed. In its place, a uniform tariff was imposed on all imports into Australia and the Customs Tariff 1908 legislation gave preferential treatment to British goods. Tariffs would remain Australia’s major source of revenue until the federal government took responsibility for income tax in 1942.

For a booming industrial nation such as the United States, tariffs on its products entering Australia would remain a sore point for decades. After the First World War, this displeasure swelled when Australia protested at the US Tariff Acts of 1922 and 1930 that imposed duties on Australia’s principal exports to the United States at the time, notably wool, which remained Australia’s major export commodity until the late 1960s.10 The US State Department acknowledged this tension in government briefing notes at the time, which also accepted, perhaps begrudgingly, Australia would be crucial in the event of another war.11 Emblematic of the spiky relationship was the Australian Government’s appointment in 1918 of its first commercial representative in the United States, Henry Braddon, who made an office in New York and reported directly to the prime minister about negotiations with American shipbuilders for supplying 14 ships – to the Commonwealth Shipping Line.

The preferential trading between Commonwealth countries frustrated the United States, particularly because it had adopted the unconditional most-favoured-nation (MFN) principle as a cornerstone of its trade policy in 1923. The MFN principle essentially means countries cannot ordinarily discriminate between their trading partners; it would be the first article in the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which came into effect in 1948, and a basic principle of the World Trade Organization (WTO). Some exceptions are allowed, such as free trade agreements that apply only to goods traded within the group or allowing developing countries special access to their markets. Currently, MFN means every time a country lowers a trade barrier or opens up a market, it has to do so for the same goods or services from all its trading partners.12

Despite these obstacles, trade between the United States and Australia had been growing, increasing fourfold from 1900 to 1927 before the Great Depression pushed two-way trade back to 1900 levels by 1933-34.13 The Depression was economically regressive in more ways than the financial calamity afflicting stock markets; it also sparked a new wave of protectionism as nations attempted to ring-fence their own economies. The protectionism preceding the Great Depression accelerated with individual governments resorting to high tariff barriers, competitive currency devaluations to gain trade advantages and discriminatory trading blocs, which exacerbated economic instability. Global trade fell by two-thirds.

One ring-fence, in particular, may have been damaging to the US-Australia relationship in 1932. The Commonwealth nations formalised their trading ‘club’ with the signing of the Ottawa Agreements on trade policy, a preferential trading system between the United Kingdom and Commonwealth countries, including Australia.14

Harry Bridges

Many American workers might have an Australian born in Melbourne in 1901 to thank for their conditions and rights. Harry Bridges, left home at the age of 16 to become a maritime seaman, which led to working as a seaman and dockworker in San Francisco in 1922. He joined the International Longshoremen’s Association rather than the employer-sponsored ‘Blue Book Union,’ resulting in his blacklisting. During the pivotal Great Maritime Strike of 1934 that shut down west coast ports and led to violent confrontations on the docks, Bridges was prominent in union strategy and negotiations which led to a stronger union and improved conditions for members. He emerged as an assertive and loyal leader although to employers his militancy and fiery socialism were alienating. In 1937, Bridges and colleagues established the International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union and his power increased to such a point his enemies, including Congress, sought his deportation on the grounds he was a member of the Communist Party of the USA. He twice appealed successfully to the US Supreme Court. He became a US citizen in 1945 by which time he was known as a charismatic opponent, negotiator and one of the most influential labour leaders ever.

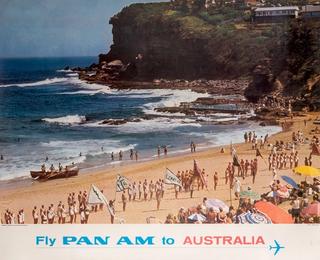

When Prime Minister Robert Menzies visited Washington DC in 1941, American attitudes to Australia’s predilection for Commonwealth trade favouritism remained frosty, with US briefing notes ahead of his visit saying relations had been highly unsatisfactory, ‘even acrimonious,’ due to trade disagreements.15 One particularly contentious commercial stance prior to the Second World War was Australia’s longstanding refusal to allow American air services, primarily Pan American Airways (Pan Am), to land in Australia. The British wanted one of its own airlines to establish a round-the-world service via Hong Kong and Australia and then to Hawaii. Australia bargained on behalf of the British, denying Pan Am landing rights while the United States held up British access to Hawaii. Yet Pan Am’s M-130 flying boat China Clipper crossed the Pacific to Manila on 22 November 1935, becoming the first to bridge the Pacific and the first airline to cross any ocean, so it had a compelling business case for flying to Australia.16

Another practical consideration hindering trade between the United States and Australia was the Commonwealth anachronism in which all radio and cable traffic between the two counties travelled through intermediaries like Canada or the United Kingdom, resulting in a five-and-a-half-hour delay. The United States realised if it were to be involved in a war, ‘instantaneous telegraph communication with Australia would be of the utmost importance.’17

The Second World War, and the transplant of the Allied supreme military command, the South West Pacific Command, to Australia in 1942 accelerated communications links. Ultimately, any post-war security threats in the Indo-Pacific outweighed any trade imbroglio between the United States and Australia. Seemingly intractable trade conflicts also cracked under the burden of the war. In 1940, for instance, the US War Department suspended the requirement that only US domestic wool be used in military orders for clothing and blankets, allowing Australian wool to be imported.

The Second World War upended global politics and commerce while the redrawing of borders along with new economic frameworks and trade agreements would reset the 20th century.

Bretton Woods and the promise of free trade

At the Dumbarton Oaks Conference in 1944, the United States, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, the United Kingdom and China agreed to the structure of what would become the major intergovernmental organisation, the United Nations, before the Bretton Woods System was established in 1946.

This meeting of 44 nations at the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, worked under the American premise that free trade would promote economic prosperity and global peace.18 Bretton Woods was also adopted as a starting point for the Atlantic Charter issued by US President Franklin Roosevelt and UK Prime Minister Winston Churchill in August 1941, in which the United States and the United Kingdom committed ‘to further the enjoyment by all States of access, on equal terms, to the trade and to the raw materials of the world which are needed for their economic prosperity.’19

The two paramount results from Bretton Woods were the establishment of the International Monetary Fund and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (later the World Bank). Currencies were also to be stabilised by linking their value to gold although the underlying goal of establishing free trade remained a potent subtext.

That was codified a year later when 23 nations, including Australia, signed the GATT agreement in Geneva on 30 October 1947.20 The agreement intended to boost economic recovery after the Second World War by liberalising global trade through eliminating or reducing quotas, tariffs and subsidies. Australia’s GATT dealings would become problematic in the following decades though, as it remained a relatively passive participant, seeking exclusion from a broad reduction of tariffs because it wanted to protect its burgeoning manufacturing industries. GATT’s exclusion of agricultural products meant a large swathe of Australia’s exports were not covered in the GATT agreements.21

In Australia, Prime Minister Ben Chifley’s actions aligned with the global economic mood. Chifley was focused on Australia’s economic security, which would be emboldened by expanding economic ties beyond its traditional reliance on the United Kingdom. In a policy speech on Canberra radio on 2 September 1946, he signalled this lessening in economic reliance on the United Kingdom, particularly the convention of exchanging Australian raw materials for manufactured British goods. Australia now intended to be an exporter of manufactured goods to Asia, Chifley said, and British, Canadian and US manufacturers had to set up in Australia to best trade with Asia. Importantly, Chifley said Australia wouldn’t hide behind tariff walls but would cooperate with the American endeavours to ‘free international trade from unduly restrictive barriers.’22 This was despite Chifley’s privately held belief the United States was just as intent on economic domination as the Soviet Union.23

Chifley’s ambitions for local manufacturing received a fillip in 1948, when Australia’s first mass-produced family car, the FJ Holden, rolled off the assembly line on 29 November. Holden had been a subsidiary of the US-based General Motors since 1931 when the original Australian company, Holden’s Motor Body Builders Ltd, supplied car bodies for imported chassis and engines. After the Second World War diverted its efforts to the construction of vehicle bodies, field guns, aircraft and engines, both Holden and Ford (and Chrysler-Dodge and the United Kingdom’s Rootes and Nuffield groups) responded to the Australian Government’s request, from the Department of Post-War Reconstruction, for studies on possible investment in the production of the first Australian-designed car.24 The Australian Government ultimately backed Holden because its study required less government assistance than Ford’s. Ten years after the first FJ Holden in 1948, half a million Holden cars had been manufactured.25

Ford and Geelong

American car manufacturer Ford’s sponsorship of the Geelong Football Club is the longest sporting sponsorship in the world, according to the Guinness World Records. The partnership will celebrate 100 years in 2025. The Australian subsidiary of the US Ford Motor Company was established in Geelong in 1925 when Ford was producing Model Ts. The relationship in that year married the regional Australian rules football club with the city’s major manufacturer. The US company retains a presence in the region with its global research and development hub in Geelong and a Proving Ground in the nearby YouYangs. Australia remains a key product development hub for Ford, with the company investing more than A$2.5 billion in research and development in Australia between 2016-20 to remain Australia’s largest automotive employer. Its team of more than 2,500 engineers, designers, technical, automotive and other specialists working at four locations across Victoria develop vehicles sold in more than 180 markets globally, including the Ford Ranger pickup and Ford Everest SUV.

An economy transforming

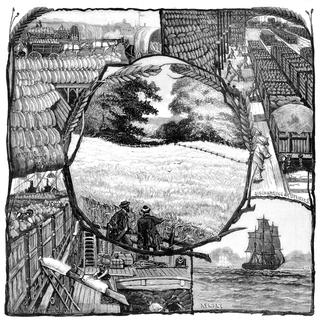

Post-war, Australia’s economic fortunes flourished. In 1950, its terms of trade reached its second-highest peak26 – 65 per cent higher than the 20th-century average – as wool, wheat, sugar and beef found more global markets.

Towards 1960, Australia gradually reduced many of the import and tariff restrictions that caused angst with partners such as the United States in favour of industry assistance policies, including production quotas and government subsidies (such as tobacco, wheat and dairy industry schemes).

Still, US trade was limited. In 1960, the United Kingdom remained Australia’s best customer, taking almost 40 per cent of Australia’s exports and providing 30 per cent of its imports, while the United States took less than 10 per cent, mainly in wool, meat and minerals. This would change quickly.

As the world opened, Australia protected itself from Great Britain’s own move towards joining the European Economic Community (EEC) by increasing trade with Japan and the United States. Even so, the formation of the EEC’s Common Market in 1957 challenged Australia’s trade before the United States overtook the United Kingdom as Australia’s most important trade partner in 1967,27 and then Japan took over in 1971 (largely due to iron ore exports).

Understandably, as Europe turned inwards, proposals for a free trade area including Japan, Australia, the United States, Canada and New Zealand began to be floated, without success. The United Kingdom officially joined the EEC in its first membership enlargement in 1973, meaning the United Kingdom-Australia Trade Agreement had to cease. This coincided with Australian economists concluding Australia’s high tariff environment limited the nation’s ability to compete globally.

The Whitlam government introduced an across-the-board 25 per cent tariff reduction in 1973 after an urgent review of tariff arrangements.28 Admittedly, this was a response to rising inflation and a booming economy rather than trade measure, as Australia shifted its trade allegiances from traditional European partners to Asia and the United States. Yet the competitive tension between Australia and the United States lingered due to their similar economic profiles in agriculture and, to a lesser extent, manufacturing. The United States complained of Australia’s high tariffs during the 1970s yet the Australian economy of the 70s was not fully formed and still sought protection, no matter the global zeitgeist.29 Conversely, the Reagan administration of the 1980s would be strong advocates for subsidies and protectionism for US farms.

Globalisation coincided with the Indo-Pacific’s emergence as the most dynamic part of the global economy, to which Australia was happy to hitch its wagon. During the 1970s, only one East Asian economy was bigger than Australia: Japan.30 In 1995 (and still in 2021) that number grew to three: Japan, South Korea and China.

The Australian Government of Bob Hawke understood that Japan and China, and the increasingly powerful economies of Korea, Taiwan and ASEAN countries were set to ensure the Pacific Rim would be a major influence in world economic affairs for the rest of the century.31 While there was pressure to concentrate on bilateral and regional trade agreements, Hawke and his treasurer Paul Keating preferred to pursue free trade and economic liberalisation through multilateral negotiations, in part because two major trading partners, Japan and South Korea, were opposed to bilateral agreements.

The Hawke government also appreciated a small economy would need to float its currency in a global economy in order to be competitive. The crucial uncoupling of the Australian dollar in 1983 allowed the exchange rate to vary with the forces of supply and demand and gave the Reserve Bank greater control over domestic financial conditions.32 US direct and portfolio investment increased dramatically, boosted by the almost simultaneous deregulation of the banking system, allowing foreign banks to acquire an Australian banking authority for the first time in 1984. This flood of US investment would become a key structural feature of the Australian economy helping ensure Australia’s economic development for decades to come.

Australia also gained some economic moxie in this period. In 1986, Australia was concerned the United States was subsidising wheat sales to the Soviet Union, for instance, so it leveraged the hosting of joint facilities as a bargaining chip.

“The Clinton administration has found a path out of the puzzling uncertainties of the late 1980s. The path is trade and it goes west across the Pacific.”Prime Minister Paul Keating, New York, September 1993

Also that year, Hawke’s government brought to Queensland 14 governments wanting to liberalise trade in agriculture, including Brazil and Canada, with the aim to challenge and reduce agricultural subsidies by the EEC and the United States. The ‘Cairns Group,’ which now has 19 agricultural exporting members accounting for more than 25 per cent of the world’s agricultural exports, has since made significant gains for its members, particularly when the Uruguay round of GATT trade negotiations concluded in 1993 after seven years of consultations.33 Multilateralism was supplanting Australia’s previous conviction that bilateral free trade agreements between large economies and more vulnerable smaller countries were best.34

The major advance in multilateralism for Australia and the United States was the formation of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) in 1989 (see chapter 4). To a large extent, APEC helped keep the United States in the Indo-Pacific and established a framework from which Indo-Pacific free trade proposals could prosper.

The Hawke government reduced tariffs in 1991 and at APEC’s Fourth Ministerial Meeting, in Bangkok in September 1992, an APEC Eminent Persons Group released A Vision for APEC: Towards an Asia-Pacific Economic Community, which recommended the goal of free trade.35 The push was on and the prospect of a free trade agreement between the United States and Australia was a logical step, particularly after the 1994 implementation of the North America Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) between the United States, Canada and Mexico.

Indeed, US Under Secretary of State for Economic and Agricultural Affairs, Robert Zoellick proposed a bilateral FTA during the 1990s but Australia wasn’t keen due to its commitment to APEC and antipathy to FTAs from its bigger trading partners, China, Japan and South Korea.

As recounted at the United States Studies Centre’s celebration of 15 years of the Australia-US Free Trade Agreement in 2020, Zoellick said the United States’ first FTA was with Israel in 1985 before the NAFTA accord under the George HW Bush administration. ‘The real first concrete proposal of an Australia-US FTA was one that I actually put into a re-election document for President Bush 41 in 1992 when I was serving as deputy chief of staff. So, it was part of a campaign plan for the future. The initial reaction of the Keating government was…I’ll say, “cool,” but we lost the election anyway.’

Even without an agreement in place, research suggests the presence of the Alliance between Australia and the United States was beneficial for trade. Between 1960 and 1990, researchers found the presence of an alliance led to an increase in bilateral trade of around 120 per cent than would otherwise be the case.36

When the United States overtook Japan as Australia’s largest trading partner in 1996, the factors hastening an Alliance free trade agreement were mounting. This was multiplied by the Asian financial crisis of 1997-98, wherein Australia contributed to International Monetary Fund rescue packages for some of the countries most affected, including Indonesia, Korea and Thailand. Certainly, the economic crisis dulled the gloss of a bounteous economic future in Asia that previously beckoned. And it propelled the momentum for an Alliance FTA, which otherwise might have dissipated.

Free trade blossoms

The idea of an FTA progressed within the broader Alliance agenda. Australian Trade Minister Mark Vaile raised the prospect in 1999, and its salience grew after the World Trade Organization Seattle talks failed that year and other countries formulated their own FTAs. With the security aspect of the Alliance on a strong footing within the new, warm relationship between the Bush and Howard governments in 2000, the prospect of a bilateral trade agreement moved to the top of Australia’s foreign policy agenda early in 2001.

Politics pushed it along. As Zoellick describes, ‘I had the wonderful opportunity which you don’t often have in history, in 2001, of having a second chance.38 So I guess I would turn this around for your Australians and say we were trying to court you for at least 10 years, and you were just playing hard to get on this issue!’ Prime Minister Howard and President Bush discussed a free trade agreement in 2001, the day before the terrorist attacks of 9/11.39

In November 2002, US Trade Representative Bob Zoellick visited Canberra and formally announced America’s intention to negotiate an FTA with Australia. Initially, an FTA was viewed more as a way to inject some of the closeness of the security Alliance into the countries’ economic relationship and not so much as a means to seek traditional trade benefits for certain sectors. Indeed, agricultural issues remained a sticking point through negotiations and even upon signing. In particular, sugar was saccharine. ‘The sugar lobby in the United States is a terribly protectionist lobby,’ Zoellick explained. ‘Because in the Senate, you’ve got two senators, we’ve got a lot of sugar states because of sugar beets as well as sugar cane and I couldn’t run the risk that those guys would hold this up. So, I couldn’t include any sugar even though the prime minister made his best efforts for Queensland and others.’40

Vaile noted this agricultural impasse specifically when outlining the arguments for a deal beyond the economic gains: additional US investment to Australia; greater integration of business between the two markets; and the demonstration effects of ‘competitive liberalisation’ for other WTO members. Specifically, he noted an FTA ‘would help engender a broader appreciation – in both countries – of our alliance and our common role in helping underpin the stability and prosperity of East Asia and the Pacific’ which was ‘now doubly important given the nature of the threats to security – and especially to Western interests – in the region.’41

The first round of Australia-US FTA negotiations began in Canberra the following March and Australia’s contribution to the US-led invasion of Iraq accelerated American interest to do a deal.42 Prime Minister John Howard enthused in 2004 the FTA was a ‘once-in-a-generation opportunity to link the Australian economy with the greatest economy the world has ever seen.’43

Yet the agreement attracted criticism. Some argued it would weaken Australia’s desire to push for multilateral trade liberalisation under the WTO and was a retrograde move away from the anticipated bounty of Asia’s economic future. And the United States didn’t appear to be giving up as much as it had in other bilateral agreements, particularly in agriculture.44

Cultural diplomacy won the day, as Zoellick tells it. ‘At the end of the day, while we were going to have difficult issues, we knew that if we could pitch this as voting for a country, as opposed to a deal, that we were in good shape.’45 The unique US-Australian relationship was enough to secure the deal. Australian Ambassador to the United States Michael Thawley later said, ‘My commission from the legislative affairs part of the White House was 80 Democrat votes,’ and he made it.

As President George W Bush signed legislation for the first bilateral preferential trade and investment agreement between the two countries on 3 August 2004, it was apparent the wider consequence for the Alliance was essential. Bush recalled ‘for nearly a century, our two nations have been allies in war and partners in peace’ and ‘our commitment to political and economic freedom remains firm.’ He added, the FTA ‘expands our security and political alliance by creating a true economic partnership.’46

AUSFTA came into force on 1 January 2005. The most impactful result was more than 97 per cent of Australia’s non-agricultural exports to the United States (excluding textiles and clothing) became duty-free and two-thirds of agricultural tariff lines went to zero.

The AUSFTA was an innovative agreement, going further in spelling out protections for intellectual property, access to procurement and investment rights than previous trade deals. Importantly, it bolstered the strategic alliance between the two nations formalised with the ANZUS Treaty in 1951.

The economics stacked up quickly, especially as Australia benefitted from the roaring demand for resources to stoke growth in China. The AUSFTA helped Australia in this instance, for example, with Australian resource companies able to exploit the mining boom more fully with imported machinery and equipment from a major producer of heavy machinery for the mining sector, the United States, no longer burdened by heavy tariffs.47 Among other changes, the tariff on Australian light commercial vehicles and auto parts was removed, as were tariffs on Australian horticultural products including oranges, mangoes, mandarins, strawberries, tomatoes, cut flowers and fresh macadamias, and Australia could export avocadoes and peanuts to the United States for the first time.48

The overall effect of the AUSFTA for both nations has been extensively assessed. Initially, academics Richard Harris and Peter Robertson argued in 2009, the commitment and insurance value of the AUSFTA could be worth as much as 0.5 per cent of Australian GDP per capita.49 But the AUSFTA has seen US goods exports to Australia increase 76 per cent since it went into effect in 2005 and US services exports more than double in the same period.50

The aim to bring greater integration of the two economies, giving an economic dimension to the strategic alliance, has also been evident. During the global financial crisis of 2007-08, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd was particularly concerned about the possible failure of the US financial behemoth AIG, to which, the Australian Treasury said, up to 30 per cent of the Australian insurance and reinsurance market had exposure. Rudd recounted he called President Bush to tell him AIG’s survival was vital to Australian interests. According to Rudd, Bush responded, ‘I hear you loud and clear, Kevin.’51 The US Federal Reserve bailed out AIG, for reasons beyond Australia’s concerns, which would ultimately cost it US$122 billion. But an Australian prime minister felt heard.

It went both ways and Australian Treasurer Joe Hockey learned the hard way. Hockey was planning to reject a takeover offer of GrainCorp on national interest grounds. ‘Little did I know there was a secret agreement between (US Trade Representative) Bob Zoellick and Mark Vaile (to consult with the White House before a negative decision was made involving a US company),’ he told the United States Studies Centre in 2020. He described this clause as a ‘side letter’ accompanying AUSFTA.

In 2018, Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull called on Australia’s deep relationship with the United States to gain exemption from tariffs the United States imposed on steel and aluminium imports from other trading partners. Initially, the Trump administration said Australia would not be exempt but Turnbull argued, and the US Government accepted, Australia had demonstrated it was a steadfast security partner.52 Conversely, in the same year, Turnbull proposed offering a chunk of Australia’s A$2.5 trillion superannuation pool to help unlock funding for President Trump’s US$1.5 trillion infrastructure push.53

The United States was Australia’s third-largest two-way trading partner in goods and services in 2018-19, worth A$76.4 billion, and accounting for 8.6 per cent, behind China (dominated by Australia’s major export, iron ore and concentrates) and Japan.54 APEC members accounted for 73.2 per cent of Australia’s total trade.

For trade of services alone, the United States remains on top (A$27.7 billion in 2018-19).55 And the United States has been the largest source of foreign investment into Australia for more than 30 years; Australia has received more direct investment from the United States than China, Japan, Mexico or even all of Africa and the Middle East combined. At the same time, the United States has also been the largest destination of Australian foreign investment for many decades.56 Today, more than 10,000 Australian companies sell to, or operate, in the United States.

The economic benefits for the United States remain substantial given it has run a healthy trade surplus with Australia every year since 1952.57 In 2019, the United States’ US$28 billion trade surplus with Australia was its third-largest, despite Australia’s size. Over 94 per cent of US goods exports to Australia are manufactured goods. Australian companies such as Atlassian, Bluescope, Brambles, CSL, Lendlease, News Corp, Pratt Industries and Rio Tinto directly employ more than 150,000 American workers.58 And, notwithstanding the pandemic, normally Australia’s single biggest export is travel services: in 2019, 1.3 million Australian tourists visited the United States spending US$7.5 billion on hotels, restaurants, shopping and attractions.59

Australia has proven to be an appealing and profitable market for US companies for many years. It offers very few barriers to entry, a familiar legal and corporate framework, and a sophisticated yet straightforward business culture.

Today, the economic footprint of Australia and the United States in each country is profound. Investment between Australia and the United States is a powerful driver of economic growth in both countries. The capital and goods and services flows are matched by the free flow of people (notwithstanding the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic), intellectual property, research and ideas between the two countries. Most of the tensions between the two similar agricultural markets have been addressed while the two countries’ shared values, similar legal and political frameworks and cultural affinity promise further trade and investment prosperity. The benefits of Australia’s first free trade agreement with a major economy continue to be felt.

By 2030, the Indo-Pacific is expected to be home to the world’s five largest economies: China, the United States, India, Indonesia and Japan.[^60] The Alliance has established the foundations for both Australia and the United States to benefit.

Michael Thawley AO

Secretary of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (2014-16), Australian Ambassador to the United States of America (2000-05), International Advisor to Prime Minister John Howard (1996-99)

Why did Australia want a free trade agreement with the United States and how did we get it? Here is my personal perspective.

It was an unusually fast negotiation. It began in March 2003. A capable veteran negotiator Steve Deady led the Australian team; his US counterpart was the experienced Ralph Ives. Less than a year later, on 8 February 2004, Trade Minister Mark Vaile, with Prime Minister Howard authorising him the night before, signed a draft text with US Trade Representative Bob Zoellick. Three months later on 18 May, the two trade ministers signed a legally ‘scrubbed’ text. The US House of Representatives and Senate passed the implementation act with exceptionally large majorities in July. President Bush signed the agreement into law on 3 August. The Australian Parliament ratified it on 13 August.

Sounds easy. But just getting to the negotiating table was a major challenge. And instructive stories can be told about each of the subsequent steps, in Canberra and in Washington DC. Many in both places thought an FTA was not politically feasible, and of course, some thought it should not happen.

The FTA entered force on 1 January 2005. Australia’s economic space widened by several multiples to include, in the United States, the world’s most competitive and innovative economy. Australia’s economy became more open to accelerated investment, technology transfer and robust competition, all of which could help lift productivity, the source of enduring prosperity.

In a separate and discreet negotiation, the Australian Embassy persuaded Congress in May 2005 to pass legislation establishing a unique E-3 visa category for professionally qualified Australians. This gives an immense advantage to ambitious young Australians who want to test themselves by working in the United States.

My personal FTA memories start in the late 1980s with Greg Wood, who raised the option as head of DFAT’s North American division. A highly regarded head of the trade office in Washington, he later became a distinguished deputy secretary in the Prime Minister and Cabinet office and High Commissioner to Canada. A leading economist, Professor Richard H Snape, was asked to do a study. He saw little advantage in an FTA, and the idea died.

In 1992, inspired by Bob Zoellick as White House deputy chief of staff, President George HW Bush proposed an FTA with Australia as part of a network of US agreements. This did not fit Prime Minister Keating’s Asia-Pacific vision. He aimed to supercharge APEC, integrating the United States, China, a newly enabled Japan, and Indonesia (the natural leader of Southeast Asia) with Australia and others into a free trade area and a politico-strategic framework that would help stabilise the region as China’s strength grew. So Bob’s proposal received a dusty answer from us.

In those decades, one could still say the best trade solutions, especially for an open and medium-sized economy such as Australia’s, were to be found in global trade agreements or at least multilateral agreements. By the time I was appointed ambassador to Washington DC at the end of 1999, a different world was emerging. The violent protests against the WTO ministerial conference in Seattle earlier that year illustrated the shift in the politics of trade within the United States and elsewhere.

In 1997, I had been with Prime Minister Howard on the way to Washington DC when the Clinton administration gave him the option of being hit with tariffs on lamb exports to the United States before he arrived or after he left the city. I drafted a press release for him which accused the United States of being hypocritical, which excited the accompanying Australian journalists and infuriated the White House. It seemed a fairly straightforward description of the situation.

I reached Washington DC in early 2000 sure that our trade tactics were inadequate. When had we last won a trade fight with the United States? The lamb case taught me that it was no use waiting for the State Department, Pentagon or even the White House to help out. Politics was the key; that was why the Clinton White House chose to toughen up the lamb restrictions while we were misguidedly seeking its help. That is another great story.

Two features of the wider economic relationship struck me. First, we had not fully appreciated the extent and political significance of Australia’s investment in the United States (at the time we were the eighth-largest investor): how widespread it was geographically (in well over half the states), how diverse (including notably in manufacturing) and how positive for American jobs. Australians were at the helm of corporate icons such as Coca-Cola, Ford, McDonald’s, News Corp and Philip Morris. Moreover, Australia was a huge customer of US defence companies. In the embassy, we began to create a ‘map’ of Australia’s economic engagement in the United States, as a foundation for our networking and political campaigning.

The second was that despite our strong history as an ally, our large-scale investment, and an extraordinary Australian diaspora active in business and the arts, Australia had no political constituency within the United States such as existed for the Irish, the Indians, the Italians, the Jewish community and others. I could make a cogent case for the United States to lift sanctions on lamb – US lamb production, sales and returns actually went down after the United States imposed tariffs. But those were just talking points, not effective political pressure or votes on the Hill.

John Howard had told me on my departure to fix our trade problems, chief among them lamb. I saw how an FTA could help us create a political constituency and a more active business constituency. It would not eliminate all trade disputes, but it would give us some locus standi. During the US election year of 2000, the embassy and I set about persuading the future US administration and our government in Canberra that it was the way to go. Moreover, it would consolidate and balance our longstanding politico-strategic alliance.

Serious economists had some good reasons against bilateral agreements. My question to them was what better means did they have for safeguarding our trade interests and for opening up the US agricultural market when multilateralism was as dead as a dodo – as the abortive Doha round soon proved.

Could bilateral agreements not ratchet up market opening through competition? My conviction was strengthened by the priority an incoming Bush administration might see in trade with Latin America, giving a leg up to our agricultural competitors – Brazil, Argentina and Chile.

Once George Bush entered office in 2001, we needed his commitment to a deal. John Howard’s discussions with him were critical in getting there. Then we needed Congress, key US companies and US business organisations to push the administration hard to open negotiations. Bob Zoellick needed first to win trade promotion authority from Congress. I wanted the president to lay down a deadline (despite fears from some in Canberra that this would be a tactical mistake) as I could see Congress was going to become less open to passing trade deals.

We were reminded of the urgency of our agenda, when in its first year the Bush administration imposed tariffs on steel, including on Australian exports. The need for some institutional constraint was obvious. We understood the political (and financial) dynamics and we moved fast and hard. This was the first major trade attack Australia clearly repelled. It wasn’t a drawn-out process with visiting delegations and press statements. The embassy got Australian steel exempted within days. That is another great story.

Luckily, Australia and our embassy were blessed with talented officials. Individuals make a difference. They all went on to prominent roles in government and business. The two deputy chiefs of mission, Meg McDonald and Peter Baxter, were widely respected and influential in Washington DC. The two chief trade officials Anastasia Carayanides and Jan Adams were masters of tactics and trade law (a key asset given the US approach to trade negotiations). Our two congressional liaison officers, Andrew Todd and Tanya Smith, were superb operators on the Hill. As John Howard observed in his memoirs, we had access that other embassies could only dream of.

We could build on the appreciation by many in Congress, the business community and administration of the strategic and economic weight of Australia, and our value as an ally and friend. We had partners who were committed to steering this ship into port in President Bush, his top political, national security and economic advisers (Karl Rove, Condi Rice, and Larry Lindsey), his outstanding ambassador in Australia, Tom Schieffer, Vice President Cheney, key figures such as Colin Powell, Rich Armitage and Don Evans – and above all Bob Zoellick as US Trade Representative.

Read Chapter 7 of The Alliance at 70: Cultural connections and creativity

.jpg?rect=0,80,3000,1989&fp-x=0.5&fp-y=0.44772296905517583&w=320&h=212&fit=crop&crop=focalpoint&auto=format)