Australia and the United States have a lot in common: liberal, democratic institutions; advanced technology; largely open economies; growing populations; infrastructure needs; and above all, abundant energy resources.

But new research published by the United States Studies Centre (USSC) shows that with respect to energy, Australia and the United States are on radically different paths. Research lead and economist Alex Robson makes clear that at the same time Australia faces an energy crisis – stressing households and threatening the very existence of some of the country's large industrial users of energy – the United States is reaping the benefits of an energy boom, delivering inexpensive gas and electricity, driving a renaissance in American manufacturing and economic growth.

Why is the USSC engaging with this topic? In 2017, we published a landmark study documenting the depth and value of the US-Australia investment relationship – far and away Australia's largest investment relationship – with more than $1.5 trillion in the two-way investments. In our fieldwork, when discussing the prospects of investments both from and in the United States, Australian manufacturers repeatedly told us the country was not a growth market for their businesses. Instead, they were investing in growing their American footprint. "Australian manufacturing is doing great", one CEO said, "just not in Australia".

Existential threats

And why are Australian manufacturers so down on their home market? In a word: energy. The US-Australia comparison in today's report vividly highlights that Australia's energy woes go beyond household electricity bills. The cost of electricity and gas for large, industrial consumers of energy is making Australian manufacturing uncompetitive. Relatively high labour costs are more or less baked into the Australian social compact. But when another critical business input – energy – becomes as expensive as it has, many Australian businesses face existential threats.

And why are Australian manufacturers so down on their home market? In a word: energy.

Good policy in this domain rests on an understanding of the basic facts of the matter and the facts are striking.

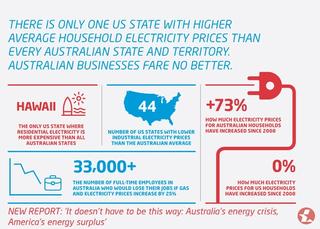

Hawaii is the only state today with higher residential electricity costs than all Australian states, while 44 US states have lower average industrial electricity prices than the Australian average. Since 2008, Queensland prices for industrial gas have risen 197 per cent, while prices have fallen in every US state. In New South Wales, industrial gas prices have risen 133 per cent in the last decade while Californian industrial gas users have seen prices decrease by 35 per cent.

Compared with their American counterparts, Australian households and businesses pay dramatically more for their energy. American electricity is supplied with greater reliability and tariff transparency than in Australia. At the same time, the rate of decline in Australian carbon emissions from electricity generation over the last decade (11 per cent) is less than half the US rate of decline (28 per cent).

Little surprise then that Australia's industrial users of energy look at the US as an attractive place to invest and grow, or, alternatively, worry about competition from US sourced imports.

Economic modelling

Energy is a non-substitutable good, consumed by households and businesses alike. High energy costs therefore reverberate through the entire economy. Economic modelling in our report suggests a 25 per cent increase in electricity generation prices and domestic gas prices costs more than 33,000 Australian jobs and 1.15 per cent of GDP. The modelling may actually underestimate the impact of significant price increases.

It doesn't have to be this way. In fact, it wasn't this way only a few years ago. Indeed, Australia and the US have in many ways reversed their energy situations over the past decade.

It doesn’t have to be this way: Australia’s energy crisis, America’s energy surplus

The study posits that the key factor in the US has been the responsiveness of markets and policy to increases in energy costs. Higher prices triggered exploration, resource development and increases in supply. When prices rose, more supply was forthcoming. That is how well-functioning markets – backstopped by sound government policy – are supposed to work. In contrast, in Australia the investment and supply response to recent higher domestic energy prices is muted.

As has become all too obvious, resource abundance will get the Australian economy only so far. Increasing energy supply is not enough. Institutional arrangements and property rights, market competitiveness, the infrastructure that gets energy from producers to consumers and regulatory and policy settings all play critical roles. The architecture of Australia's energy markets requires reform, if not transformation. With more favourable institutional and the right policy settings, the market can transform physical abundance into economic abundance, putting downward pressure on energy prices and emissions.

Australia's flawed policy is also a system of a flawed debate. Achieving emissions reduction and lowering energy prices are often seen in a zero-sum lens. Indeed, the past decade of debate in Canberra reflects this. But as the US energy revolution reveals, emissions reduction, increased supply and reassurance for industry and households alike need not be mutually exclusive outcomes.