Executive summary

Australia enjoys a remarkable benefit from its multi-faceted, two-way investment relationship with the United States. And while Australia’s trade relationships, particularly in the region, are vital to continued growth and prosperity, the United States remains Australia’s indispensable economic partner.

Since its founding, Australia has been a heavy importer of foreign capital, and that foreign capital is a crucial driver of employment, economic growth, and also the ability to export. While much is often made of Australia’s important trading partners, including China, the important investment partners make those trading relationships possible by providing the necessary capital and know-how for production of goods and services.

US investment in Australia is currently A$860 billion: That’s A$345 billion more than the next largest investor, the United Kingdom.

The cumulative value of two-way investment between the United States and Australia is more than A$1.47 trillion, a number nearly as large as Australia’s gross domestic product. Representing more than a quarter of all foreign investment in Australia for many decades, the cumulative stock of US investment in Australia is currently A$860 billion: That’s A$345 billion more than the next largest investor, the United Kingdom, and approximately ten times more than Chinese investment in Australia.

These investments are indicative of a long and deep relationship between countries that have a great deal in common. Secure property rights and procedural fairness – backed by the rule of law and democratic political institutions in both countries – mean that Australia’s economic relationship with the US spans access to capital, technological diffusion, and knowledge transfers. In each of these domains, the United States is Australia’s most valuable partner.

This report addresses three fundamental components of the US-Australia investment relationship:

- its size, history, and economic impact

- the role of capital markets

- the “spillover effects” from foreign investment, namely skills and knowledge transfers

The report takes a multi-pronged approach, analysing this vital relationship from a variety of angles.

US-Australia investment overview

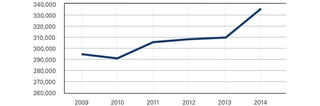

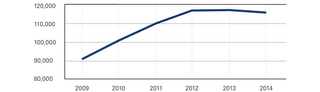

Having represented around a quarter of all foreign direct investment into Australia for over three decades, the stock of US direct investment in Australia is approximately A$195 billion – more than any other country. Critical sources of economic growth, these investments span all sectors of the economy and are responsible for more than 330,000 high-paying jobs with US-affiliated firms in Australia (average salary more than A$115,000), annual capital expenditures of more than A$10 billion, and annual research and development spending of more than A$1 billion since 2009.

The US-Australia investment relationship is not a one-way street. The United States has long been the single largest destination of outbound Australian investment, comprising more than a quarter of all Australian overseas investment. Total cumulative Australian investment in the United States is estimated to be A$617 billion – more than seven times the A$87 billion that Australia has invested in China. More than 1,200 Australian firms have operations in the United States, 12 per cent of which have assets or income greater than US$20 million. Australia exports to the United States in 2016 were worth US$9.5 billion – a fraction of the US$60.6 billion that Australian-owned companies made in sales in the same timeframe. Major Australian firms, ranging from biotechnology giants like Resmed to property giants like Westfield Corporation, see the United States not just as a market responsible for more than half of their global revenues, but as a springboard to the world.

The stock of US direct investment in Australia is approximately A$195 billion – more than any other country.

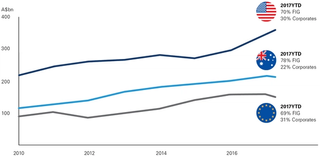

The critical role of US capital markets

US capital markets, especially debt markets, are a vital source of capital for Australian companies, especially the banking and financial services sector. Australia’s “Big 4” banks (Commonwealth Bank of Australia, Westpac, National Australia Bank, and the Australia and New Zealand Banking Group) are the four largest ASX-listed companies and account for nearly one-quarter of the total market capitalisation of the ASX 300. The Big 4 banks are heavily reliant on wholesale funding from US debt markets. Due to foreign exchange markets, the depth of US debt markets, and interest rate derivatives, the United States is the overwhelming source of that funding.

This all has positive spillovers for the banks’ ability to lend to Australian individuals and businesses – the core building blocks of Australia’s economy. From the capital for infrastructure programs to major levels of investment for superannuation funds, US capital markets affect practically all Australians.

Business attitudes towards foreign investment

The knowledge and skills transfer that result from US investment into Australia are often described by business leaders in Australia as one of the most valuable benefits of the investment relationship with the United States because it enriches the competitiveness and level of skill available in the Australian economy.

To quantify this value, a survey was conducted of business leaders in Australia. Surprisingly, non-US owned firms operating in Australia generally valued US expertise less than Australian expertise. At the same time, however, there was very clear evidence that all the firms valued expertise, ownership, and an increased market share in the United States more than China or Japan.

Case studies

Thirteen businesses with strong ties between the United States and Australia were profiled in case studies interspersed throughout this report. The businesses profiled engage in diverse sectors including technology, manufacturing, retail, finance, infrastructure, oil and gas, pharmaceutical, and defence.

Focusing particularly on what compelled them to go overseas, US businesses place a high value on Australia’s low sovereign risk, highly skilled labour force, and strategic location. At the same time, however, businesses are increasingly worried about growing levels of instability in the investment climate. Some see Australia at risk of losing access to a globally mobile labour if business immigration regulations are made more difficult and housing affordability is not improved.

Policy recommendations

- Immigration. Continued transfer of highly skilled overseas personnel to US companies operating in Australia requires a continued commitment to skilled migration programs such as the subclass 457 visa, and a pathway to permanent residency.

- Cities. Part of the attraction of Australia as a place to work is Australia’s “lifestyle dividend”. But housing affordability and infrastructure pressures in major cities like Sydney and Melbourne are challenging. Ensuring that Australian cities are great places to live and work is important to attract human as well as financial capital to Australia.

- Investment certainty. Uncertainty deters investments of all kinds, and Australia’s energy and climate change policies over recent years have contributed significantly to general policy uncertainty. Long-term clarity must be provided.

- Tax rates. Australia’s company tax rate has, in the space of 15 years, gone from being among the lowest in the OECD to one of the highest, at a time when reductions in rates by the United States and the United Kingdom are on the horizon. A more favourable tax rate would attract more financial capital to Australia.

- Barriers to investment. Australia and the United States have in the past made preliminary plans to reduce barriers to more investment of smaller equity stakes, known as portfolio investment. These plans should be seen through and implemented.

- Statistics. The data currently available from the Australian government, unlike other countries, lacks the granularity necessary to understand the nature of inward and outward foreign investment in Australia. More data is needed to better document and understand the magnitude and importance of Australia’s investment relationships.

Foreword

From the United States Studies Centre

Simon Jackman, Chief Executive Officer, United States Studies Centre at the University of Sydney

Australia’s relationship with the United States runs deep and broad, and has for a long time. For this reason, it is easy for Australians − particularly younger generations of Australians − to underestimate the value of Australia’s relationship with the United States.

The depth and breadth of the relationship is evident in numerous domains: defence and national security, science and technology, the creative industries, and – the subject of this report – investment.

Economic historians classify Australia as resource-rich, but capital poor. Today’s Australia – technologically advanced, prosperous, and optimistic – is the legacy of generations of individuals, households, enterprises, and government. Insufficiently understood by many Australians is the American contribution to these nation-building investments.

The depth and breadth of the relationship is evident in numerous domains: defence and national security, science and technology, the creative industries, and — the subject of this report — investment.

These investments have taken several distinct forms, each of which are detailed in this report. Direct investments by American firms – typically via establishing and building Australian subsidiaries, developing plant and equipment, or acquiring a significant stake in an Australian enterprise – now totals $195 billion and has been growing by more than $10 billion a year in recent years; far and away the largest single source of foreign direct investment in Australia. US-sourced portfolio investment – typically, American institutional investors taking equity positions in Australian enterprises – was valued at $522 billion in 2016. In addition, the depth of US capital markets and the ease with which Australian financial institutions can access those markets play a vital “behind the scenes” role in the Australian economy, providing liquidity and security to the Australian financial services sector and their customers, Australian firms and households.

Case studies breathe life into the analysis. The stories of numerous American corporations and their investments in Australia – as well as Australian companies investing in the United States – highlight the long history and ongoing value of the investment relationship.

The United States Studies Centre is Australia’s leading institution for analysis of Australia’s relationship with the United States. On behalf of the Centre, its Board, staff and stakeholders, I’m proud that the Centre is shining a bright light on this vastly under-appreciated and under-valued dimension of the US-Australia relationship.

This study – supported by the American Chamber of Commerce in Australia – is a key part of a broader Centre effort to help Australians understand the depth and importance of Australia’s economic relationship with the United States.

As this report demonstrates, much is at stake in the Australian-US economic relationship. Good policy in this domain rests on an understanding of the basic facts of the matter. With this report, the Centre is making a valuable contribution to an issue of great national importance.

I thank Professor Richard Holden, the principal researcher on this project, for his leadership and labours on this project; Jared Mondschein, project manager and editor; Joseph Daley and Jaron Lee, who worked as research assistants on this project. In addition to their prodigious intellects and work ethic, Richard, Jared, Joseph and Jaron have invested passion, creativity and commitment, evident in the pages of this report.

I especially thank Niels Marquardt and the American Chamber of Commerce in Australia, who have been our partners on this project, helping the Centre fulfill its mission of educating Australians about our relationship with the United States. May this be the first of many such partnerships in the months and years ahead.

From the American Chamber of Commerce

Niels Marquardt, US Ambassador, ret’d; Chief Executive Officer American Chamber of Commerce

The American Chamber of Commerce in Australia (AmCham) is proud to have been the catalyst for this important new body of research created by the United States Studies Centre on the unsurpassed but under-appreciated two-way investment relationship between the United States and Australia.

First and foremost, we would like to thank the AmCham member companies and other friends whose anonymous contributions generously funded this study, or who supported its launch in other useful ways. We could not have done it without this exceptional level of interest and support.

It was one year ago that the AmCham Board of Directors gave its “green light” to initiate this study. Our directors realised that the extraordinary dimensions of American investment into Australia were insufficiently understood by the Australian public. They decided that media, politicians, regulators, academics, and other key actors would all benefit greatly from a sharp, fresh insight into the critical role American foreign investment has played – and, hopefully, continue to play – in building a robust and prosperous Australian economy. And they were concerned about the policy implications of a continuing lack of awareness of this investment and its many impacts. Since there was no “off-the-shelf” independent reference to which one could turn, we wanted to create one for use by the broader community here.

It is a little-known fact that Australia is home to more US investment than any other country in the entire Asia-Pacific region.

As we undertook this project, we were grateful for the many leaders who already appreciated the critical importance of this relationship, and for their parallel efforts to call it out for what it is. Foreign Minister Julie Bishop, as a leading example, has repeatedly called the United States “Australia’s most important economic partner”. She has explicitly recognised the enormous contributions that American direct foreign investment has made to Australia’s unbroken quarter-century of uninterrupted economic growth – a new world record. This investment comes on top of a robust two-way trading relationship that has gone from strength to strength since the Australia-US Free Trade Agreement entered into force in 2005.

This study sets out in concrete terms, particularly through 13 fascinating case studies, why this investment matters so much. Consider job creation, which is clearly the top policy priority in both the United States and Australia. By our reckoning, roughly one in 12 jobs in Australia is directly or indirectly the result of US investment here. Just consider how many people you know personally who have great jobs working for the American companies profiled in this report, like Amazon, Amgen, Bechtel, Boeing, Cisco, Citi, Costco, Exxon Mobil, Google, GM Holden. Each of these investors has created thousands of jobs across Australia. In this respect, no other country’s investment in Australia comes close.

It is also worth noting that the economic impact of Australian investment in the United States – the leading destination for Australian foreign investment – has also been significant. This study is as much about this story – about trailblazing Australian companies like Incitec Pivot, Austal, and Lendlease – that are among a swathe of Australians developing a sizeable presence in the American market.

This may be the “Asian Century”, but this study also helps unpack how American investment has made it possible for Australia to benefit so much from opportunities in Asia. It is safe to say that, without American investment, technology, talent, and equipment, Australia’s engagement with Asia would look significantly different. Indeed, this story is a “win-win-win” for America, Australia, and Asia, and it demonstrates why US investment has been such a powerful force in shaping foreign investment-dependent economies such as Australia’s.

So far, Australia is an unparalleled success story in terms of US investment. With only 23 million consumers, Australia nonetheless has become a major world market for many American companies – far in excess of what mere population and GDP would lead one to expect. Australia tends to welcome American products and innovation more readily than just about anywhere on earth – and the Australian people collaborate energetically in the trans-Pacific exchange of new ideas with America. Furthermore, it is a little-known fact that Australia is home to more US investment than any other country in the entire Asia-Pacific region.

Given these facts, the challenge faced by our directors was that public opinion in Australia largely fails to perceive most of this. For example, a recent United States Studies Centre (USSC) survey determined that Australians prefer increased trade with China more than increased trade with the United States. Our concern is that public perceptions such as these can lead to perverse impacts on policy formulation. Our main objective at AmCham is that Australia continues to offer the most welcoming possible climate for foreign investment so that the prosperity already created here can continue to grow, long into the future. The fact is that, in an increasingly globalised world, Australia competes for the marginal investment dollar with every other country. The policy settings in each country matter greatly in decisions on where to invest, and we strongly advocate having the most globally competitive settings here in Australia. Facilitating the entry of foreign capital, talent, and technology into the country is critical to this desired outcome.

AmCham is hopeful that this important work by the USSC will help galvanise a vigorous, fact-based discussion of how American investment has indeed contributed to building Australia, and how it can continue to do so. In voicing this hope, please also allow us to express our deep appreciation to USSC CEO Professor Simon Jackman, the USSC Board of Directors, lead researcher Professor Richard Holden, and the many colleagues who assisted them in this important endeavour. Their extraordinary interest, creativity, curiosity, expertise, and diligence have combined to produce what I hope you will agree is an extraordinary contribution to an important national discussion in Australia.

Australia’s ties with the United States

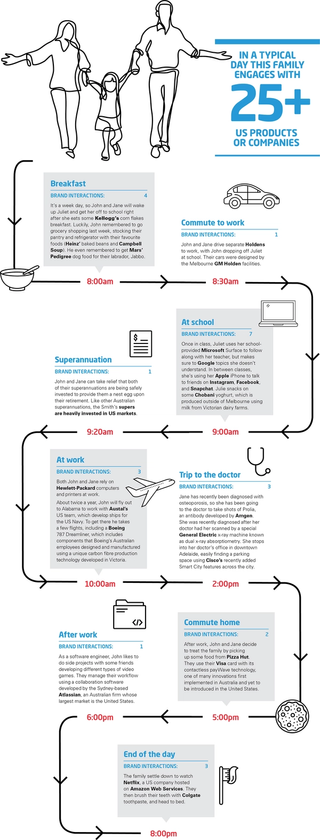

The US and Australian economies are so deeply intertwined that the connections can go practically unnoticed. A typical Australian household engages with US products or companies in almost every aspect of their life.

Meet the Smiths

Take this hypothetical Australian family living south of Adelaide. Let’s call them the Smiths.

Taking advantage of his naval experience, John works as a project manager at the ship-building company, Austal, an Australian firm with most of its employees and business in the United States.

His partner, Jane, commutes down to Millicent to work as a manager at Kimberly-Clark, the largest single employer in the region.

John and Jane live with their 12-year-old daughter, Juliet, in a home that was financed by an Australian bank. With a quarter of funding for Australian banks being foreign, the bank is financed with US capital secured through Citi.

Case study overview

This report includes 13 case studies of businesses with strong ties to both the United States and Australia. These are the result of discussion with a broad array of business leaders throughout Australia.

The 13 businesses profiled engage in sectors including technology, manufacturing, retail, finance, infrastructure, oil and gas, pharmaceutical, and defence. They also have markedly unique histories in Australia. GM Holden, for example, is one Australia’s oldest and most storied foreign investments and is maintaining a world-class design capability in Australia while ceasing its local auto manufacturing, while Amazon Web Services, having begun operations in Sydney less than a decade ago, is now growing almost exponentially.

Although economic data and survey results can be important indicators of the quantitative value of foreign investment, the insights gleaned from these discussions helped us to form some of the most valuable conclusions of our research.

Ten of the 13 businesses profiled are US businesses in Australia, with the remaining being Australian businesses with strong US ties. For each one, we specifically asked what led to their investment overseas, what strengths the US and Australian business climates provide them and also what they hope will improve in Australia’s business climate.

Here in Australia, some of the issues that the businesses raised, particularly in regards to challenges, we summarise without attribution. Although economic data and survey results can be important indicators of the quantitative value of foreign investment, the insights gleaned from these discussions helped us to form some of the most valuable conclusions of our research.

A few key themes on what attract US companies to Australia include:

- The quality of life is one of the best in the world. This sees Australia not only attract highly skilled and internationally mobile individuals, but it is also a compelling place for them to settle. Families are drawn to Australia’s good healthcare system, strong schools, low crime rates and unblemished physical environment. These “lifestyle dividends” have been enormous for Australia.

- It is often underappreciated just how much Australia has benefited from its good governance. In a region beset with tensions and instability, Australia is a safe and inviting country for investment with strong democratic institutions and traditions, allowing for little sovereign risk. Whether it be the development of classified military technology or expensive research initiatives, companies trust that Australia is a safe place for their most sensitive of operations.

- The remote nature of Australia has benefited Australia in a number of ways. It has fostered an environment in which Australians love to travel and are eager to see the world. Companies in Australia know that they can draw on a talent pool with international experience and appetites to travel more. It has also led to an innovative culture where Australians create and supplement local solutions to various challenges without much outside help.

- Australia’s considerable difference from the United States is also, ironically, conducive to close collaboration with US firms. It is not only a great launch pad for US firms seeking to enter the Asian market, but it is also located in a time zone that allows firms to maintain business operating hours outside of typical US and European business hours.

- Australia’s world-leading universities supply companies with a high-skilled workforce. They also, however, are collaborative partners to a diverse array of companies in Australia. Countless innovations and discoveries in Australia have originated from public-private research and development collaborations with Australia’s universities.

- The Australian population is more tech-savvy than most developed countries, having embraced the digital world faster than most. Foreign companies often introduce cutting-edge technology in Australia ahead of other markets because it is a developed yet still secluded market, so the impact of failure is less.

Some of the Australian challenges that business articulated, both present and future, included:

- As much as the mining boom helped Australia safely navigate through the financial crisis, Australia’s economic future lies in services-centric investments, not capital-intensive investments like mining. This means high skills jobs, not itinerant low-skilled labour. Australian labour, even unskilled labour, is not cheap – particularly compared to the United States. Many businesses with slim profit margins are working to decrease their reliance on this expensive commodity.

- A more services-centric investment strategy, most notably in terms of attracting and maintaining high-skilled labour from around the world, starts with a constructive immigration policy. The current reforms to the 457 visa stand out as being particularly unfavourable to businesses in Australia being able to attract the high level of talent necessary to stay globally competitive.

- A basic tenet of the economic theory of investment is that, all else equal, greater uncertainty makes investment less attractive. From the hurried implementation of new bank taxes to dramatic reversals in energy policy, there are increasing levels of instability in Australia’s investment climate. Further instability can have long-term economic consequences.

- Australia’s “lifestyle dividends”, which have paid so handsomely for Australia by attracting such a significant amount of high-skilled labour, are becoming increasingly difficult to maintain. Exorbitant housing prices in Sydney and Melbourne – the two cities that attract the majority of foreign talent – are making it increasingly difficult to maintain talent. Furthermore, the urban environment – ranging from infrastructure and public transportation, to school systems – will face increasing pressure given projected population increases.

- Australia’s corporate tax rate is now one of the highest in the developed world. Companies will not be inclined to stay in Australia if other developed nations go ahead with their plans to lower their corporate tax rate even further.

- Australian businesses benefit from the government’s Trade and Investment Commission (Austrade) being active and engaged in helping Australian businesses abroad. Ultimately, foreign businesses in Australia must deal with local governments that are sometimes not as business-friendly as governments elsewhere, including the United States. Austrade’s many efforts to take local Australian government delegations on tours of more business-friendly environments should continue and be expanded, if possible.

The US-Australia investment relationship

What does this investment in Australia ultimately look like? It is thousands of US subsidiaries or US facilities located throughout Australia, with more than 1,000 US companies earning or valued at more than US$25 million, according to US government statistics.1

- As Australia’s largest investor and the largest destination of Australian investment, no single country plays a larger role in Australia’s economy than the United States.

- The cumulative value of two-way investment between the United States and Australia is more than A$1.47 trillion, a number nearly as large as Australia’s gross domestic product. The United States alone has over A$860 billion invested, $345 billion more than the United Kingdom, the second largest investor in Australia.

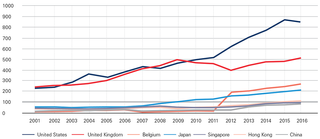

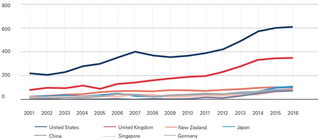

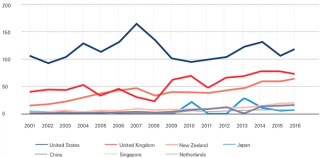

- The United States has had substantial investments in Australia since the early 20th century, yet the amount of investment has grown sizably over the past 15 years, particularly since the financial crisis. Today, the total US investment in Australia has more than tripled since 2002.

- While China has rapidly increased its levels of investment in Australia, it remains only the seventh largest investor in Australia, with total investments amounting to one-tenth the magnitude of US investment. Even in terms of outbound investment, Australia’s investment in the United States is more than seven times greater than its investment in China.

The state of New South Wales alone is estimated to have more than 1,500 US subsidiaries operating within it.2

There is no doubt that proportionally, the US-Australian investment relationship has a larger impact on Australia than it does on the United States. Indeed, Australia is only the seventh largest destination of US Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). Nonetheless, Australia is the recipient of more US FDI than all of South America, Africa, or the Middle East, receiving well over twice the amount that China does.3

History

The US-Australian economic relationship dates as far back as 1793, when the American trading ship Hope delivered 7,500 gallons of rum to Sydney.5 It was not until the turn of the 20th century, however, that the economic relationship began to truly flourish. The earliest estimates of US investment in Australia date back to 1896, with the establishment of the Ammonia Company of Australia in New South Wales by the US-owned National Ammonia Company.6 Less than ten years later in 1908, upstate New York-based Kodak began to develop film in Australia through a joint venture with a Melbourne company.7 By the 1930s, major US multinational manufacturers such as Kellogg’s, Ford, General Motors, Heinz, and Coca-Cola had all set up Australian operations.8

The 1940s, particularly the economic activity engendered by World War II, proved to be a major turning point in the US-Australia economic relationship. According to David Uren’s 2015 book on foreign investment in Australia:

“…the Australian economy was swept into the task of supplying the US war machine in the Pacific. The US Lend-Lease program delivered the latest US plant and equipment to upgrade Australia’s manufacturing capability for delivering everything from bomber aircraft to radios, steel, ships, clothing and tinned chilli con carne. Production of canned vegetables went from 4,000 tons at the beginning of the war to 60,000 tons by the end … At the end of the war, a deal was cut under which Australia would pay the United States $27 million (about 9 million pounds) for the Lend-Lease equipment it was leaving behind. The war left Australia with a much larger and more sophisticated manufacturing base than it had five years before, and it also deepened links between Australia and the United States.”9

By the 1950s, US foreign investment around the world had grown, nearly tripling from $11.7 billion to $31.9 billion by the end of the decade, but it would grow fastest in Australia.10 The rapid increase in post-war foreign investment not only benefited the capital-thirsty Australian economy, but also “provided access to much of the technical knowledge and managerial skill developed in the more industrially advanced countries of Europe and North America”, according to a 1964 study of US investment in Australian industry by Don Brash, the future governor of the Reserve Bank of New Zealand.11 The Australian Treasury Department in 1958 found that foreign direct investment, much of it being American, “helped us invaluably during recent years by the support it has given to our balance of payments, by the addition it has to investible funds within Australia and by the accompanying flow of new techniques and know-how”.12 According to Brash, the combination of foreign capital and foreign skills transfers was “a vital force impelling growth throughout the [Australian] economy”.13

In proportional terms, the United States has accounted for around a quarter of all inbound investment in Australia since the 1980s.

Led by the United States, foreign ownership of Australia’s oil refining, car, and pharmaceutical industries was estimated to be more than 90 per cent by the 1960s. By this point, Brash opined that “most Australians would have difficulty naming a breakfast food, a cosmetic, or a toilet article not produced by the local subsidiary of some American company”. As much as the Australian Treasury and economists may have seen the value of foreign investment, its rapid growth coincided with increased popular anxiety over the magnitude of foreign ownership and growing fear of foreign powers.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) had grown so rapidly that “both nationalist and state developmentalist ideas gradually became more influential”, eventually leading Australia to turn “away from a long-established ‘open door’ policy towards FDI”.14 This period, which lasted well into the 1980s, would lead to the creation of the Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB), advising the federal treasurer on foreign investment into Australia.

A target of controversy, FIRB has continued to play a critical yet often-maligned role in helping the government regulate foreign investment – although as FIRB is an advisory body, broad discretion ultimately remains with the treasurer. The 2005 US-Australian Free Trade Agreement, which substantially increased the FIRB screening threshold for US investments into areas deemed to not have national security implications, has helped to lower that barrier to US investment. Interestingly, beyond just US investment, one economist suggests that the free trade agreement led to “an increased stock of FDI from all sources due to the wider liberalisation in Australia’s foreign investment rules” after it went into force.15

Nonetheless, it was not until the 1980s, when foreign investment regulations were relaxed, that US investment into Australia began to look as it does today. The value of US investment since that time (figure 1) has dramatically increased in value, but this coincided with a similarly dramatic growth of all investment into Australia. Accordingly, in proportional terms, the United States has accounted for around a quarter of all inbound investment in Australia since the 1980s.16

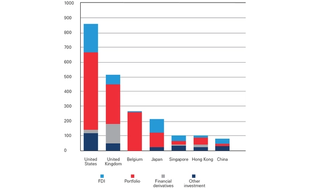

Foreign investment generally takes four different forms: direct investment, portfolio investment, financial derivatives, and other investments. Foreign direct investment (FDI), defined as foreign ownership of 10 per cent or more of a company, makes up 25 per cent of total foreign investment in Australia. Foreign portfolio investment, generally defined as foreign ownership of less than 10 per cent of a company, makes up 52 per cent of all foreign investment in Australia. Seven per cent of foreign investment in Australia comprises financial derivatives, largely foreign currency hedging, while the remaining 16 per cent is defined as other investments, a residual category that covers any items, such as trade credits or loans, that are not defined elsewhere.

Given its more enduring nature, FDI is often seen as being the most valuable form of foreign investment. Having been the largest single foreign direct investor into Australia for many years, the United States now accounts for nearly a quarter of all cumulative inbound FDI, totaling A$195 billion (figure 3). From aerospace to agriculture, US direct investment in Australia takes place in practically every sector of the country’s economy.

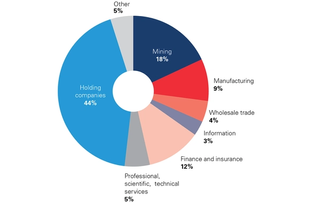

According to US government data, the top sectors attracting US FDI into Australia are holding companies, mining, finance and insurance, and manufacturing. The outsized role of holding companies in US FDI into Australia is actually consistent with the global trend of increasing amounts of US FDI being in the form of holding companies. Tasked with holding securities or assets of other companies, many organisations engage in the use of holding companies for overseas investment for tax considerations.

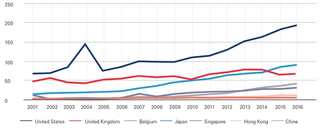

The United States has been the largest destination of Australian investment for many years. Making up more than 28 per cent of all Australian overseas investment, total Australian investment in the United States is valued at A$617 billion, more than seven times the A$87 billion that Australia has invested in China (figure 6). Major Australian firms, ranging from biotechnology giants like CSL to innovative tech firms such as Atlassian, see the United States not just as a large market but as a springboard to the world. The amount of Australian investment in the United States continues to grow significantly, having already doubled its total investment amount since 2005.

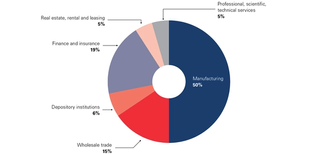

With significantly lower labour costs than Australia, manufacturing makes up half of Australia’s direct investment in the United States. This report’s case studies of Australian firms with significant operations in the United States, like Austal and Incitec Pivot, further detail the incentives for investing in US manufacturing.

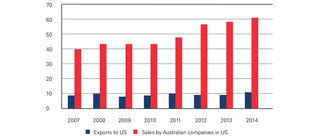

Australian exports to the United States in 2016 were worth US$9.5 billion – a fraction of the US$60.6 billion that Australian-owned companies made in sales in the same timeframe (figure 8).

What does this investment mean for Australians?

This substantial economic relationship ultimately results not only in more jobs for Australians but also higher quality jobs. The most recent US government data estimates that US-affiliated firms account for 335,400 jobs in Australia, with wages totaling A$38.8 billion – meaning that, on average, an Australian employee of a US-affiliated firm earns more than A$115,000 a year. Although the impact of foreign investment remains intangible by many measures, no statistic demonstrates the deep value of US investment in Australia better than the A$1 billion and more that US companies in Australia have spent annually on research and development (R&D) since 2009 (figure 11). To put that into perspective, US companies in Australia spent more than A$1.5 billion on R&D in 2014, while the Australian government pledged A$9.5 billion for R&D in 2013-2014.

US-affiliated firms account for more than 335,000 jobs in Australia with an average annual salary of more than A$115,000.

Conclusion

Trade, the provision of goods or services for money, is relatively simple in both theory and practice. Investment on the other hand comes in multiple forms and often requires understanding how investments and markets evolve over time. While trading relationships can fluctuate rapidly from year to year, bilateral investment relationships are based on the belief that the future will be more prosperous than the present. The sizable investment relationship between the United States and Australia is a clear vote of confidence in the strength and security of both countries, of their political and legal institutions, and the US-Australia relationship more generally.

The importance of US capital markets

Australia is a nation that relies heavily on international capital markets. At a very basic level, Australia needs a continual inbound flow of capital in order for the economy to continue to grow. This is true in both debt and equity markets. Debt matures and must be repaid or rolled over, meaning that the funding needs of the nation are ongoing and significant drivers of economic growth.

The increase in both household and government debt, particularly in recent years, makes this funding necessity even more pressing.

In debt and equity markets, and for the vast majority of financial products, US capital markets are the deepest, most liquid, and most reliable for Australian entities (public or private) with funding needs. In 2016, corporate debt issuance in the United States totalled US$1.5 trillion, with total outstanding issuances of US$8.5 trillion.30 To put that in context, the entire GDP of Australia is around US$1.4 trillion.

US debt markets are the mainstay of global debt markets. As one industry participant put it “they are always open; there’s always a price”. Another said, “the US is the home of capital markets – and the biggest single thing is the depth of US markets, at all points of duration”. That is, where “duration” refers to the time that the debt is outstanding.

This can be seen in a straightforward way from the following chart decomposing Australian debt issuance by currency of issue. US dollar denominated issuances dominate Euro-denominated issuances by a very wide margin.

The banking sector

The Australian banking sector is a large and crucial part of the economy. In fact, the four largest publicly traded companies on the Australian Stock Exchange are the so-called “Big 4” banks: Commonwealth Bank (CBA), Westpac, ANZ, and National Australia Bank (NAB). Their combined market capitalisation as of 1 June, 2017 was A$402.9 billion, or 23.9 per cent of the ASX 300 index. When adding in Macquarie Bank, this figure increases to 25.7 per cent.

The Big 4 Australian banks, with their good credit ratings and cheap borrowing capabilities, have large balance sheets and are particularly reliant on wholesale funding (i.e. funds in addition to demand deposits). In a December 2016 review of CBA’s funding position, ratings agency S&P Global Ratings concluded that the “CBA and the other Australian major banks are materially reliant on wholesale funding”.31 Although there were some concerns about the stability of this funding in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, it is now generally accepted that the Australian banking sector is generally sound and has passed appropriate “stress tests”.32

The US market is not only completely indispensable as a source of funding for the Big 4 banks but this fact has significant flow-on benefits for Australian mortgage holders as well as businesses to which the Big 4 banks lend.

To get a sense of the size of wholesale funding used by Australia’s banks, consider the largest player, CBA. In 2016, CBA relied on wholesale funding for 36.0 per cent of its total funding, a slight decrease from 36.9 per cent in 2015.33 Australian banks have a foreign funding ratio of 24 per cent, with 11.8 per cent of capital being foreign short term and “rolled over” on a regular basis. The one quarter of the Big 4’s funding coming from offshore sources is largely sourced from the United States and is more than triple the amount that comes from shareholders.34

Our research has found that the US market is not only completely indispensable as a source of funding for the Big 4 banks but this fact has significant flow-on benefits for Australian mortgage holders as well as businesses to which the Big 4 banks lend.

Interestingly, Australian mortgage holders also benefit in another, somewhat more direct way from US investment. The enormous amount of cash held offshore by major US companies such as Apple, Google, and eBay are often invested in overseas securities. These companies have been seeking out Australian housing exposure, thus lowering the funding costs of Australian mortgage holders.

Other sectors

US debt markets are also vital for non-bank Australian issuers. In addition to public offerings, the US private placement market (USPP) and offerings under Rule 144A of the Securities Act of 1933 (144A), nonpublic or unregistered debt offerings, are popular among Australian issuers. USPP and 144A offerings allow Australian issuers a great deal of flexibility, particularly in issuing debt of different durations. US pension funds are a vital player in such markets. The size of US pension funds is important in underpinning this flexibility.

The fact that many Australian companies have significant US revenues also makes US debt markets attractive for reasons to do with foreign exchange exposure. There are now currently more than 40 ASX-listed companies which have approximately 30 per cent or more of their revenues denominated in US dollars. Notable examples include Mayne Pharma (87 per cent), James Hardie (80 per cent), Westfield (69 per cent), and ResMed (61 per cent).

Public sector debt

Since the financial crisis of 2008, the Commonwealth of Australia has run persistent budget deficits of a significant size. Total (gross) Commonwealth debt stood at just over $420 billion at the end of 2016.35 Given the growing size of this debt, along with existing debt maturing, the annual issuance amount is sizeable. For instance, in 2016 A$80.2 billion of treasury bonds were offered, along with $15 billion of treasury notes.36

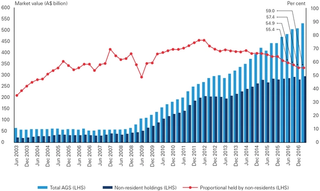

The following chart shows the material proportion (now 55.4 per cent) of total Australian Government Securities on issue held by non-residents of Australia. It is immediately clear that international markets are extremely important for Australia to fund its day-to-day governmental operations, and the United States is estimated to be a very sizeable purchaser of Australian government securities.37

Australian superannuation funds in the United States

Although it is natural to focus on the tremendous funding needs of Australian entities that are often met in US capital markets, it is worth emphasising that there is also significant outbound investment from Australia to the United States.

The area where this is largest and most notable is investment by Australian superannuation funds into the United States. According to OECD figures39 Australia has the third largest pension fund assets in the world, behind the United States and the United Kingdom. At the end of March 2017, the total size of Australian superannuation was approximately A$2.3 trillion,40 an impressive sum given that the total market capitalisation of the ASX 300 on 1 June 2017 was A$1.689 trillion.41

It is estimated that more than A$500 billion, more than 20 per cent of Australia’s total sum of superannuation funds, is invested in the United States.

A significant factor behind this is the 9.5 per cent superannuation guarantee, Australia’s compulsory employer-paid system of superannuation saving for employees introduced in 1992. According to current legislation, the Superannuation Guarantee rate will increase to 10 per cent from July 2021, and eventually to 12 per cent from July 2025.

The sheer size of the Australian superannuation sector relative to investment opportunities in Australia necessitates looking for offshore investment opportunities. Added to that, there are sound reasons for diversification by investing offshore, with the United States a large and attractive market.

It is estimated that more than A$500 billion, more than 20 per cent of Australia’s total sum of superannuation funds, is invested in the United States at the present time.42 A substantial amount of this investment is in the US infrastructure market by Australian superannuation fund managers such as IFM – the largest manager of Australian infrastructure assets and the third largest infrastructure investor in the world.43 This means that Australian workers are invested in the renewal and revitalisation of US airports, roads and bridges.

Why US markets?

A natural question to ask is why US debt markets seem so preferable to other markets, such as European markets. The overwhelming response from market participants – both issuers and banks that facilitate issuance – is the depth, reliability, liquidity, and flexibility of US markets.

US debt markets participants are underpinned by pension funds. But Australian investors have decades of experience in these markets. Ultimately, this has helped create a strong reputation, in the way that only long-run experience from lenders can. This liquidity-reputation dynamic creates a virtuous circle whereby the attractive US market causes greater Australian-company issuance, thereby increasing the attractiveness of US markets.

A natural question to ask is why US debt markets seem so preferable to other markets. The overwhelming response from market participants is the depth, reliability, liquidity, and flexibility of US markets.

Although European markets are important, our research has found them to be smaller, less liquid, and more specialised than the US market. Apart from a general “first-mover” advantage of US markets, market participants point to two other important factors. The first is the relative macroeconomic risk of Europe relative to the United States. Recent macro-political issues in Europe, such as the Greek debt crisis, the so-called “Brexit” vote in the United Kingdom, and the macroeconomic issues facing several southern European countries all speak to an increasingly uncertain macroeconomic environment. The second factor is that participants in the European debt market – such as insurance companies – typically have a different mandate and/or operating strategy than US pension funds.

Currency is also a major factor in making US markets more attractive than other markets. The Australian Dollar (AUD) is the fifth most traded currency in the world. One market participant said of the Australian dollar: “the Australian currency is a globally relevant currency – and it is increasingly used as a proxy for Asia.”

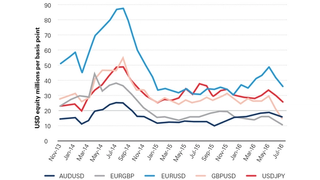

Moreover, Australian borrowers access what are essentially synthetic Australian-dollar denominated prices using cross-currency/basis swaps, a form of interest-rate derivatives. Given this, one indicator for the depth of the US market for Australian borrowers is by looking at the cost of swapping Australian and US dollar (USD) interest payments. A natural approach is to look at the interbank lending volumes in the AUD-USD market. In that market, a lower “per pip” (unit of foreign exchange price movement) USD equivalent indicates a deeper market – so moving between the AUD and USD is cheaper. The following chart shows this for a number of currencies and the US dollar. The AUD-USD line is notable, which shows how deep this market is for Australian companies.

It is also worth noting that seemingly small differences in funding costs, or maturity structure, can strongly tilt the balance towards the US market over other markets.

Summary

US capital markets have a critical role in Australia’s economy: they are an indispensable source of capital for Australian businesses. The Big 4 banks are the most obvious cases-in-point, given their large wholesale funding requirements. Their capacity to access US markets is crucial for their own funding but that, of course, flows directly on to their customers through an increased capacity to provide credit.

Australian households are a huge and clear beneficiary of this. It is not a stretch to say that Australians’ mortgages are brought to them by US capital markets.

Australian small and medium enterprises (SMEs) are also important beneficiaries. SMEs rely on Australian banks to provide them with the credit they require to maintain and grow their businesses. The access the Big 4 have to the US capital markets allows SMEs more credit, through more flexible and sophisticated products, at a lower cost.

This report touches briefly on the following point in the section on policy implications, but, notwithstanding, the very efficient “trans-Pacific pipe of capital” could be further improved and fine-tuned through greater financial-market comity. For instance, Australian issuers, typically, need two ratings for a US debt offering, in addition to significant amounts of documentation. Legal opinions, such as a 10b-5 opinion, are also involved. In fact, of the Big 4 banks, only Westpac is currently registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Greater integration would enhance financial market activity between the two countries, and have benefits analogous to free trade agreements for goods and services. As we mentioned previously, even seemingly small transaction costs of a few basis points can have material effects on behaviour, and hence investment and major growth.

Survey analysis

In early discussions with academics and business leaders concerning research on the US-Australia investment relationship, there was a common sentiment that US foreign direct investment was particularly valuable because there was a distinct benefit to having US expertise in Australian business operations.

Anecdotally, various parties said that many Australian firms would go out of their way to hire Americans or individuals with significant American expertise for their management and corporate boards. The given reasons for this strategy varied. Some offered the notion that Australian corporate boards were often “old boys clubs”, filled with old friends instead of innovative business leaders. Others opined that the typical American business mindset was simply more ambitious than the typical Australian’s.

Various parties said that many Australian firms would go out of their way to hire Americans or individuals with significant American expertise for their management and corporate boards.

While there are studies of Australian business attitudes towards specific markets – particularly Australian companies engaged in exporting – there appears to be no recent research concerning business leaders’ attitudes towards the “spill over” effects of international investment, such as better business skills. One 1964 study on US investment in Australian manufacturing by Don Brash, the future governor of the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, reported that 57 of 75 American-affiliated companies in Australia said that US technical know-how was vital to their total operation.[44]

Given the abundance of anecdotal evidence and scarcity of systemic research on the topic we conducted, a business survey was conducted to determine the veracity of the claim that Australian businesses explicitly sought out US expertise. More importantly, however, was the need to quantify the value of expertise and investment from certain countries – the United States, Japan, China and Australia – to businesses with operations in Australia.

Specifically targeted were Australian-based company representatives knowledgeable as to their company’s ownership, revenue, size, and strategy. For these reasons, C-Suite level executives were specifically sought out to complete the survey.

The online survey was conducted in May and June 2017 and was completely anonymous in the hope that respondents would give their honest answers.

Survey design

The survey was designed to be easy to complete, comprising just 33 multiple choice questions and the opportunity to add qualitative responses on an additional six optional questions. The average completion time was six minutes.

Company information sought included annual revenue, number of employees, sectors engaged in, states and territory locations, location of world headquarters, which locations the companies primarily sell their goods or services, and whether they engage in research and development.

We asked the following five questions with reference to Australia, the United States, China and Japan:

- How valuable is this country’s expertise on your corporate board?

- How valuable is this country’s expertise in your management?

- How valuable for your business is an increased market share in this country?

- How valuable is this country’s expertise in growing your business?

- How valuable is increased ownership from this country in your business?

We defined expertise as a citizen of that country or someone with significant experience or education from that country.

The available options to respondents for these questions: “no value”, “little value”, “moderate value”, “high value”, “extremely high value”, or “not applicable”.

Both the order in which the countries were listed and the questions asked were randomised.

A total of 45 company representatives with operations across Australia completed the survey. Twenty-seven of the companies were foreign owned, with all but three of the foreign-owned companies being US-owned. The median company had between 250 and 500 employees in Australia, while almost half of the companies reported A$250 million or more in annual revenue.

More than two-thirds of the companies had staff operating in New South Wales or Victoria, and just over half had staff operating in Western Australia, South Australia, or Queensland. Less than a third of the businesses had staff in the Northern Territory or Tasmania.

Around two-thirds of the companies engaged in research and development in Australia.

Given the limited sample size of the survey, it is difficult to say that the survey results confidently represent the wide array of business leader sentiment in Australia. Nonetheless, the 45 respondents provided valuable insights into the value of foreign expertise, ownership, and business ambitions.

Perhaps the most striking conclusion from the survey respondents is the fact that non-US owned firms operating in Australia generally valued US expertise less than Australian expertise. At the same time, however, a remarkable disparity appears in terms of attitudes towards US expertise compared to expertise from China and Japan. No more than 12 per cent of non-US owned respondents preferred Japanese or Chinese expertise of any kind over US expertise. Indeed, around three quarters of non-US companies preferred US board expertise, management expertise, and expertise in growing their business to Japanese or Chinese alternatives.

An oft-repeated theme in our case studies is the fact that Australia is often seen as a great launching pad into Asia, yet surprisingly few of the respondents preferred increasing their market share in Japan or China more than the United States. Only 11 per cent of non-US owned firms valued increasing their Chinese or Japanese market share more than increasing their US market share.

The value of US expertise compared to Australian expertise

Less than a quarter (16-22 per cent) of the non-US owned firms operating in Australia preferred US board expertise, US management expertise, and US expertise for growing a business, over the Australian alternative. Although a sizeable amount of the non-American firms held neutral views, about half or more (47-61 per cent) preferred Australian management expertise, Australian expertise in growing their business, and Australian board expertise over the US alternative.

American firms in Australia reported a stronger preference for US expertise over Australian expertise than non-US firms did, but not by an overwhelming margin. Indeed, American firms were split in regards to US versus Australian management expertise; with a third preferring US expertise, a third preferring Australian expertise and a third remaining neutral. Furthermore, nearly half of the US firms (46 per cent) were neutral about whether US or Australian expertise would grow their businesses.

Most American firms (52 per cent) preferred US board expertise, while most non-US owned firms (61 per cent) preferred Australian board expertise.

The most stark contrast between US and non-US firms was with respect to board expertise: most American firms (52 per cent) preferred US board expertise, while most non-US owned firms (61 per cent) preferred Australian board expertise.

The value of US ownership compared to Australian ownership

Interestingly, one notable exception to a clear preference for Australian business dealings was in ownership. While 19 per cent of non-US owned firms preferred US ownership, a similar proportion (25 per cent) preferred the Australian alternative, with more than half of the remaining respondents being neutral on the topic. This suggests that increased US ownership or investment into these non-American companies operating in Australia is generally seen to be generally equal in value to increased Australian ownership or investment.

Compared to non-US owned firms, American firms indicated more of a preference for US investment, expertise, and market share over Australia in every measure. Yet even then, the stronger preference for US investment, expertise, and market share by US firms was not as dominant as one may have expected.

US investment, expertise and market share compared to China and Japan

When compared to China and Japan, there was very clear evidence that all firms surveyed valued expertise, ownership, and an increased market share in the United States more than China or Japan. Unlike comparisons between the United States and Australia, there was little ambiguity in answers on China and Japan between US and non-US owned firms.

Between 67-82 per cent of non-US firms valued US expertise for corporate boards, management, and growing their business more than Chinese or Japanese expertise. No respondents reported a preference for Japanese expertise for growing their business over US expertise, while only one respondent reported a preference for Chinese expertise for growing their business over US expertise.

Given continued economic growth in China, surprisingly few respondents (11 per cent) valued an increased market share in China more than in the United States (57 per cent). Even fewer respondents (8 per cent) valued an increased market share in Japan more than in the United States (67 per cent).

Industry insight on Australian corporate boards

Tim Boyle, managing partner of the Melbourne-based board advisory firm Blackhall & Pearl, told us that the argument that Australian corporate boards are “old-fashioned” may have been relevant 10 years ago but is not necessarily true today. According to Boyle, who has a doctorate in corporate board performance and whose firm has advised most of the top Australian firms, Australia is on par with the United States or even better in some respects, such as governance and training.

Unlike many US boards, where there is a mindset “that you’ve got to roll the dice sometimes”, Australian boards are not as tolerant of mistakes.

Ambition and risk appetite, however, are different stories. Boyle reported that Australian boards are not as aware of risk, accepting of innovation, or tolerant of failure as many US boards are. Unlike many US boards, where there is a mindset “that you’ve got to roll the dice sometimes”, Australian boards are not as tolerant of mistakes, he says. Furthermore, while Australian boards are moving to be more skills-based, Boyle has noticed that too many have a bias to only hire people they personally know.

In terms of whether US expertise is specifically sought out for corporate boards more than Australian expertise, Boyle finds that the types of US expertise are more important than the fact that a prospective board member is American or has US experience. American managerial expertise in the technology sector, for example, would be far more valuable to an Australian board than American expertise in manufacturing. Furthermore, US commercial experience – actually engaging in the business instead of just board membership – would also be more valuable to Australian boards. The United States benefits from not only being the world’s largest market but also having the deepest “gene pool” for finding board members, so there is an obvious bias for Americans on Australian corporate boards, Boyle said.

Policy recommendations

Although the investment environment in Australia is attractive, there are clear challenges to be addressed in ensuring that this remains the case in the future. It is also worth emphasising that a spirit of “continual policy improvement”, akin to continual process improvement in business, is important to making sure that Australia does not become less attractive relative to other destinations for US investment.

From a policy perspective, we see foreign investment into Australia taking two forms. Firstly, there is investment into the physical characteristics of a country, most clearly demonstrated by the numerous mining or oil and gas investments across Australia. These are investments that companies would want to make almost regardless of the local labour force and skills. Secondly, and most relevant to Australia, is foreign investment driven by local skills and talent. Companies, particularly those engaging in innovation, want to secure the best and brightest minds working at their firms and are willing to come all the way to Australia to do it.

For Australia to continue its highly valuable investment relationship with the United States, a consolidation of some of the important reforms of the past and resistance to populist impulses will be necessary.

All of the components of this report – the economic analysis, the survey of business leaders, and the case studies – point in the same direction regarding Australian public policy.

All of these components confirm that for Australia to continue its highly valuable investment relationship with the United States, a consolidation of some of the important reforms of the past and resistance to populist impulses will be necessary.

There are six main areas where public policy can best enhance the wide-ranging Australia-US investment relationship and deliver benefits to the Australian economy.

Policy priority 1: Immigration

The 457 visa is a temporary work visa for skilled migrants to Australia that permits a migrant to work in their nominated occupation by an Australian employer sponsor for up to four years.45 The visa has provided an important path to Australian permanent residency and citizenship.

The Coalition government announced changes to the 457 visa program in April 2017 that would restrict skilled immigration into Australia. As Peter Dutton, the Minister for Immigration and Border Protection, put it:

“The existing 457 visa program… essentially it is open-ended, and it results, in many cases, in a migration outcome.

What we propose is that under the temporary skills shortage visa short-term stream there will be a two-year visa, with the options of two years, but there won’t be permanent residency outcomes at the end of that.” 46

The number of 457 visas granted is significant, averaging around 100,000 migrants per year in recent years, compared to half that amount or less 15 years ago.

Concerns have been raised that existing workers on 457 visas will have their path to permanent residency curtailed, and that employers will no longer be able to attract high-skilled workers in the technology, university, and other sectors critical to Australia’s economy.

Discussions with Australian businesses undertaken in the course of preparing this report suggest that employer fears are both important and well-founded. One of the cornerstones of the business model of many of the firms highlighted in this report, particularly those engaging in highly-skilled work, is the ability to attract highly-skilled workers of exceptional quality to their Australia operation. Part of what makes Australia an enticing destination for such highly skilled overseas workers is the presumption they will have security of tenure in the country.

While abuse of immigration regulations should be addressed, the current changes and stances of both major political parties put that certainty of tenure in doubt, and thus threaten Australia’s investment into talent by restricting the flow of highly-skilled overseas workers into Australia.

There is also the very real possibility of a backlash from other countries that limits the ability of Australian nationals to work overseas, gain expertise, and return to Australia with those skills. The Australian E3 work visa to the United States, which allows Australians in highly-skilled fields and their spouses to work in the United States, is an example of a program that could be threatened if “tit-for-tat” immigration policies are pursued. The E3 is particularly attractive for Australians, allowing up to 10,500 Australians a year to gain access to the United States for employment purposes – although that quota has yet to be met.47

In short, the two-way knowledge transfer that is a critical part of the US-Australia investment relationship is under threat unless continued flows of highly-skilled workers between Australian and US employers are maintained.

Policy priority 2: Cities

As Australia’s mining boom slows, foreign investment in the country is increasingly becoming more talent-centric than physical-centric. One of the consistent messages raised by the people-centric companies spoken to for this report is that Australia is a very attractive place for employees, and that this “lifestyle dividend” allows them to maintain their investments by attracting highly-skilled and high quality workers.

One significant threat to that investment in people is Australia’s worsening housing affordability. This issue is particularly acute in Sydney and Melbourne, where many innovative businesses investing in Australia choose to locate.

A prominent international housing affordability index recently released listed Sydney as the second least affordable major housing market in the world, with a median house price of $1,077,000 standing at 12.2 times median household income of $88,000. Melbourne was only slightly better as the sixth least affordable housing market, with a median multiple of 9.5 times the median household income.48

Some of the most attractive areas for workers relocating from overseas, such as coastal areas in Sydney with proximity to the central business district (CBD), are more expensive, still. Given the geographic size of cities like Sydney and Melbourne, living further away from these areas may not only be less attractive in terms of amenities, but also involve substantial commuting times – a significant decrease to the quality of life.

Part of the attraction of Australia as a place to work is Australia’s “lifestyle dividend”. But housing affordability and infrastructure pressures in major cities like Sydney and Melbourne are challenging.

Innovative firms like Amazon Web Services emphasised that they chose to locate their offices in the CBD because employees wanted to live nearby. Thus, housing affordability can significantly curtail the “lifestyle dividend” that Australia is seen as conferring.

There has been significant policy debate in Australia about how to best address the housing affordability crisis. It is accepted by many commentators that a combination of increasing housing supply (through land releases and changes to zoning regulations, for example), combined with a reduction in demand-side measures (such as preferential tax treatment for investment properties) is required to adequately address with the issue.49

Cities are, of course, about more than just housing affordability. Transportation infrastructure, public goods and other amenities, cultural attractions, and other factors are all important components. While Australian cities rate very highly on most of these dimensions, the forecasted increase in population numbers over the coming decades will require continued policy responses to ensure that Australian cities remain highly attractive for talent-centric foreign investment.

Policy priority 3: Investment certainty

A basic tenet of the economic theory of investment is that, all else equal, greater uncertainty makes investment less attractive. A potentially major constraint on foreign investment in Australia is policy uncertainty.

Some degree of this is present in every jurisdiction and is, to a certain extent, unavoidable. However, Australia stands out in its uncertainty regarding energy policy and climate change.

Under the Gillard Labor government, Australia instituted a carbon tax of A$23 per tonne from 1 July 2012, and then raised the tax to A$24.15 the following financial year. Upon the election of the Coalition government led by Tony Abbott in 2014, the tax was abolished.

Since that time, the government’s “Renewable Energy Target” has sought to ensure that 23.5 per cent of Australia’s energy comes from clean sources, such as wind, solar, hydro-electric, by 2020. There are also a number of state-based targets.

Recently, there has also been discussion of an emissions trading scheme or a somewhat less market-based approach recommended by Australia’s chief scientist Alan Finkel in the so-called “Finkel Report”.50

So many policy changes and the continued lack of clarity about implications for business creates investment uncertainty for all business in Australia – as energy is ultimately a significant input for all businesses. As the Business Council of Australia puts it:

The markets believe governments, locally or globally, will ultimately require carbon emissions to be reduced. Until the mechanism is made clear, markets will factor a substantial carbon risk into investment decisions. This uncertainty is discouraging investment in generation, increasingly driving up the cost of electricity.51

In all areas – but particularly energy policy – greater certainty from government would improve the investment climate to make it more conducive from all sources, particularly FDI.

Policy priority 4: Tax rates

At 30 per cent, Australia currently has the fifth highest corporate tax rate in the OECD,52 yet in 2003 had only the 18th highest in the OECD. There is a further trend among countries like the United States and the United Kingdom to potentially lower their corporate tax rates by a significant amount.

Although Australia, too, has considered lowering its corporate tax rate, present legislation envisages only a very gradual lowering of the rate to 25 per cent, and quite possibly only for companies with annual turnover below A$50 million.53

Australia’s company tax rate has, in the space of 15 years, gone from being among the lowest in the OECD to one of the highest, at a time when reductions in rates by the United States and the United Kingdom are on the horizon.

This makes investing in Australia relatively less attractive, all else equal, than investing in other jurisdictions.

A recognition that financial capital is highly and increasingly mobile is important for continued foreign direct investment in Australia.

Policy priority 5: Barriers to portfolio investment

Portfolio investment already makes up more than 60 per cent of the total US investment into Australia but further progress could be made in this area.

Nearly a decade ago, there was a push for greater comity between US and Australian financial markets, with negotiations getting to the point of preliminary agreement on a “mutual recognition framework”.54 The arrangement – signed by and predicated on further cooperation between the US Securities and Exchange Commission and the Australian Securities and Investments Commission – was intended to allow US and Australian stock exchanges and brokers to operate in both jurisdictions without being subject to additional regulations. Essentially, US and Australian investors would have been able to engage with each other’s stock markets with less red tape.

Unfortunately, however, US and Australian officials signed preliminary documents on 25 August 2008 – less than a month before Lehman Brothers declared bankruptcy and the beginning of the financial crisis. This, along with the leadership changes, ultimately resulted in no implementation of a final agreement that was intended to go into effect as early as 2009.

Another barrier to more portfolio investment in Australia is the fact that it is often inadvertently captured by the Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Act of 1975, therefore necessitating extra scrutiny by FIRB. Major foreign portfolio investors could easily take a sizeable interest in a company that requires FIRB approval yet, as passive investors, not exercise control or even have the desire to exercise control over the company. This regulatory requirement acts as a significant deterrent to foreign portfolio investment. Preliminary discussions on addressing this took place between the United States and Australia as part of the US Free Trade Agreement but no final decision was made.55

Further progress in reducing transaction costs and creating greater contracting certainty would allow for even more two-way capital flows between the United States and Australia, with concomitant improvements to investment outcomes.

Policy priority 6: Statistics

Finally, the Australian government could certainly do more to document investment flows into and out of Australia. No economic challenge can be fully addressed without an appropriate comprehension of the relevant economic data. The data currently available through the Australian Bureau of Statistics is simply not granular enough – particularly when compared to the available US economic data. Ultimately, analysis of Australia’s economic status suffers as a result. Our research is but one of a plethora of analyses on foreign investment in Australia that has concluded that more data is necessary.56

Furthermore, the Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB) has a significant amount of “nascently available” data from the applications it receives. Through an appropriate anonymising and digitising process, these could be made publicly available to researchers and the business community.

A growth of data gathered from the Australian Bureau of Statistics and a sharing of data from FIRB could better document and understand the magnitude and importance of Australia’s investment relationships.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank a number of individuals and organisations for their help on this report.

Firstly, we would like to thank Niels Marquardt and the American Chamber of Commerce in Australia for helping the Centre fulfill its mission of educating Australians about our relationship with the United States.

We would also like to thank the many participants of our case studies for the considerable time they allowed us in speaking to them.

Our analysis of capital markets was enriched by the input provided by:

- David Livingstone (Australia Country Director, Citi)

- Mark Woodruff (Managing Director for Investor Sales, Citi)

- Fiamma Morton (Executive General Manager for Client Coverage Group, Commonwealth Bank of Australia)

Other individuals who helped in the project included:

- Mark Baillie (Chairman, US Studies Centre Board of Directors)

- Andrew Charlton (Director, AlphaBeta Advisors)

- Carolyn Conner (Manager for Strategy, Communications & Research, Australian Trade and Investment Commission)

- Maureen Dougherty (President, Boeing Australia & South Pacific)

- Eamon Fenwick (Partner, Deloitte Australia)

- Stephen Kirchner (Economist, Australian Financial Markets Association)

- Wei Li (Lecturer, University of Sydney Business School)

- Kevin McCann (Chairman, Citadel Group Ltd and Dixon Hospitality Ltd)

- Greg Medcraft (Chairman, Australian Securities and Investments Commission)

- Ian Satchwell (Senior Fellow, Perth USAsia Centre)

- Danielle Szetho (CEO, FinTech Australia)

- Michael Thawley (Senior Vice President, Capital Group)

- Doug Wallace (Commercial Counselor, U.S. Department of Commerce).

Meetings with officials from the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, the Australian Trade and Investment Commission, and the Australian Department of Treasury also helped us frame the scope of our research.

We acknowledge the contributions of two anonymous peer reviewers. The report is stronger for their contributions.