The interactive component of this report is best viewed on desktop. We recommend mobile users view the report as a PDF.

Executive summary

- Innovation is critical to Australia's future. The economic and technological realities of an increasingly innovative world economy will inevitably catch up to Australia — and Australia needs to be ready. The Global Innovation Index (GII), the world's leading measurement of innovation across more than 80 indicators, shows Australia is simply not innovating enough.

- Australia ranks 23rd in the world and the GII makes it clear Australia is an inefficient innovator. Australia puts considerable effort into the elements that foster innovation — ranking 12th in the world on inputs — but has yet to see the results, ranking 30th on outputs of innovative activities. Ultimately this considerable discrepancy leaves Australia ranked 76th in the world in innovation efficiency.

- There is no doubt the United States, currently ranked fourth in the GII, is a world-class innovator — attracting much of the world's innovation output, including Australia's. As a close US ally in economic, military, intelligence, and diplomatic spheres, it makes sense to examine what Australia could learn from the United States.

- From a policy perspective, Australia would benefit from: incentivising foreign venture capital firms to be based in Australia, fostering an environment that welcomes both skilled immigrants and anchor firms, increased domestic awareness of the skills shortage in the existing and future workforce, and an international campaign that raises awareness of the role Australia can play in a global innovation ecosystem.

Australia’s world ranking in innovation is falling

Ranked as high as the 17th most innovative country in the world by the Global Innovation Index (GII) in 2015, Australia fell to 19th the following year. In 2017, Australia comes in at 23rd — overtaken by China and behind New Zealand.

Meanwhile, the US ranking in the GII’s assessment of innovative performance keeps improving. Currently ranked behind Switzerland, Sweden and the Netherlands as the fourth most innovative country in the world, the United States has never ranked lower than 11th since the GII began in 2007 and has either maintained or improved its ranking since 2010.

Why is innovation relevant in Australia?

Why is innovation relevant in a country like Australia, which has enjoyed an unprecedented quarter century of uninterrupted economic growth? Does our natural resource endowment mean we can afford to be less innovative?

Ultimately, innovation will determine Australia’s future. Innovation drives business competitiveness, new business growth, new jobs and is a key driver of economic growth. Defined by the OECD as “the implementation of a new or significantly improved product (good or service), process, new marketing method or a new organisational method in business practices, workplace organisation or external relations”, the OECD attributes approximately 50 per cent of member countries’ long-term economic growth to innovation. These economic and technological realities will ultimately catch up with Australia.

In order to maintain its productivity and lifestyle Australia has no choice but to embrace innovation.

Benefiting from more than a quarter century of continued economic growth, following deregulation in the 1980s and 1990s and a mining boom through much of the 2000s and 2010s, Australia now enjoys high wages and standards of living, as well as a strong social safety net. In order to maintain its productivity and lifestyle, however, Australia has no choice but to embrace innovation.

The importance of innovation is not lost on Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, who embraced innovation as a major early agenda item. In December 2015, less than three months after Turnbull became prime minister, the Australian government released its National Innovation and Science Agenda. Focusing on growing the innovation climate through improvements in capital, collaboration, talent and skills and the role government plays as an exemplar, Turnbull said this innovation agenda would “help create the modern, dynamic 21st century economy Australia needs”.

Why is the United States relevant?

One might argue that the United States has simply been “doing” innovation for longer than Australia, but a deeper dive into the data shows that the United States has certain characteristics that make it fundamentally better positioned for innovative growth. That is not to say that Australia lacks the ability to be more innovative. Analysing the 81 indicators of the GII provide a better explanation of these issues (as provided below).

Another question is why it's relevant to compare the United States to Australia when the United States has an economy 15 times larger and a population 13 times larger. The United States may be ranked as the fourth most innovative country in the world, but it remains a top destination for much of the output of Australia’s innovation — and much of the world’s, for that matter. The obituary for the loss of America’s innovative supremacy has been written many times, but this GII data — along with other research — make it clear such sentiment is still premature. Although many have proclaimed this to be the Asian Century, the United States still attracts the best and brightest minds for innovation, from Australia and the rest of the world.

As a close ally in economic, military, intelligence, and diplomatic spheres, it makes sense to examine what Australia does well compared to the United States and what Australia could learn from the United States. Examining how we differ on the indicators making up the GII is a good starting point.

What is the Global Innovation Index?

Produced jointly by Cornell University, INSEAD business school and the World Intellectual Property Organization, the Global Innovation Index assesses the innovation performance of 127 countries and economies around the world, based on 81 indicators. It is the most authoritative and comprehensive resource for quantifying innovation amongst nations. It also clearly articulates what Australia does well and what Australia could do better in when it comes to innovation.

The Global Innovation Index is the most authoritative and comprehensive resource for quantifying innovation amongst nations.

There has been a considerable debate in Australia (and elsewhere) as to the validity of the GII. Some have asked how you can quantify the impact of Australia’s popularisation of avocado on toast? Cafes around the world have now adopted the healthy Australian snack, which innovated a new way to use an avocado, but how is that innovation quantified in the GII measurements? The simplest answer is that avocado on toast is not quantified in the GII. But at the same time, neither is Japanese sushi or Korean Bibimbap or Scotland’s deep fried Mars bars. Ultimately, more comprehensive innovation measures should be sought after, but even then it would be unlikely improved measures would show Australia innovates more than countries ranked higher than it on the GII. Furthermore, while Australia's fondness for smashed avocado has seen Australian avocado production growth year on year for decades, it is simply not as impactful of an innovation as other Australian examples, such as Wi-Fi.

Measuring innovation is a difficult and imprecise process. The GII is by no means the only measure of innovation available. Other organisations, particularly the OECD and World Economic Forum, also analyse innovation using various data. Yet the GII has the most indicators spanning the breadth of the many components of innovation.

How the Global Innovation Index works

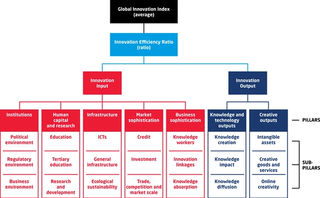

The overall ranking of each country in the GII is essentially done by averaging the scores of each country based on 81 indicators – with most scores ranging from 0 to 100. In 2017, the top composite score of 67.69 belongs to Switzerland, while the US score is 61.40 and the Australian score is 51.83.

More specifically, the 81 indicators are all located within either innovation input (which tries to capture the elements that enable innovative activities) or innovation output (which tries to capture the results of innovative activities). Within these two components are multiple pillars. There are five pillars within innovation input: institutions, human capital and research, infrastructure, market sophistication, and business sophistication. There are two pillars within innovation output: creative outputs, and knowledge and technology outputs. Each pillar is divided into three sub-pillars and each sub-pillar is comprised of a varying number of indicators.

It should be noted that the indicators and number of countries included in the GII can vary from year to year.

Interactive: Australia and US Global Innovation Index comparison

Sorting the indicators of the Global Innovation Index by score differential shows where the biggest differences are between the United States and Australia, and where the two countries are similar.

This interactive graphic can also be sorted by Australia’s maximum and minimum scored indicators and by the maximum and minimum scored indicators for the United States.

Hover over the data points to see the individual Australia and United States scores and differential for that indicator. Hover over the indicator name for the definition and data source.

Known challenges for innovation in Australia

Perhaps we can start with what was already known about the issue at hand. Given the importance of innovation to Australia’s future, extensive research has consistently shown three major areas that Australia lacks in its efforts to build a more innovative climate, especially when compared to the United States: capital, networks and culture.

Capital

As covered in prior USSC research, Australia is a resource rich, capital poor country, and has always been reliant on foreign injections of funds. For instance, if an innovative Australian company is trying to rapidly grow, the main source of capital will likely be the United States. It comes as no surprise, then, that thousands of Australians choose to live in major centres for venture capital and talent, like Silicon Valley, instead of remaining in Australia. If an Australian innovator is ambitious, Australia will likely not have the capital resources to facilitate future growth.

Networks

Along with capital, networks and serial entrepreneurs are critical for building capacity for innovation. Given the comparably less availability of capital and support networks for experienced professionals doing innovative work, many of the most successful firms simply do not stay around in Australia long enough to be impactful over the long term. Instead, many choose to go overseas — a brain drain of sorts. Ultimately this erodes Australia’s network for innovation.

While Australia has long been known for its rugged ingenuity developed in its island isolation, it lacks the ambitious and risk-embracing nature that is evident in more innovative nations.

Culture

The Turnbull government should be lauded for its initial embrace of innovation, but the fact that the government would barely mention the term just over a year into office is indicative of the political ramifications for embracing the relatively novel concept to Australia. While Australia has long been known for its rugged ingenuity developed in its island isolation, it lacks the ambitious and risk-embracing nature that is evident in more innovative nations. Data on risk taking in the Australian business environment is consistent with some stereo types about Australia, such as a Tall Poppy Syndrome and fear of failure.

Australia is an inefficient innovator

It has been clear since the first GII was released in 2007 that Australia is an inefficient innovator, today ranking 76th out of 127 countries in innovation efficiency. Essentially, Australia is putting considerable effort into trying to be innovative, but it has yet to see the results that match the effort.

Australia’s innovation inputs are indeed impressive, ranking 12th in the world when combining its scores across the five pillars of institutions, human capital and research, infrastructure, market sophistication and business sophistication. But Australia’s innovation outputs lag considerably, ranking 30th in the world, behind nations like Malta and Cyprus.

Australian strengths compared to the United States

Australia enjoys a number of remarkable strengths that make it ripe for becoming an innovative powerhouse. Of the seven pillars making up the GII, Australia is in the top 15 in the world in institutions (14th), human capital and research (9th), infrastructure (7th), and market sophistication (9th). Outside of market sophistication, Australia actually scores better on these pillars than the United States, with 20 indicators within these input pillars where Australia ranks ahead of the United States in the GII.

Education

Australia places ahead of the United States in education. Australia excels in many indicators within education, ranking first in the world in the number of years that students spend in school, averaging more than 20 years. The average American, on the other hand, spends an average of 17 years in school. Given the cost of tertiary education in the United States compared to Australia, this result is not surprising.

Australia enjoys a number of remarkable strengths that make it ripe for becoming an innovative powerhouse.

When comparing US and Australian student reading, scientific, and mathematical proficiency on a state level, the results are all the more striking. Almost all Australian states score above almost all US states.

Australia also ranks sixth in the world in percentage of foreign students that make up its university system while the United States ranks 40th. Australia’s remarkably high level of foreign university students, most of whom are from China, has been a financial boon to universities across the country.

Infrastructure and governance

As innovative as the United States is, American governments have never had much of an explicit innovation policy. A number of innovations — from the internet to bar codes to freeze drying technology — have been developed either by or with the aid of US government agencies and institutions, but the US government has by and large not successfully implemented any meaningful innovation policy, per se. This lack of policy is evident in its own processes: despite the fact that a US government agency helped create the modern internet, the US government itself is ranked ninth and 12th in the world in government online services and technology-supported participation in government processes.

The Australian government, on the other hand, is ranked second in the world both in government online services and technology-supported participation in government processes. Furthermore, Australia’s infrastructure pillar is ranked seventh while the US infrastructure is ranked 21st. The Australia government has not only taken it upon itself to implement an innovation policy with wide ranging implications for the broader society, but it has also, in many areas, become a leader in online accessibility and innovation infrastructure.

Where the United States excels compared to Australia

While Australia has strengths in innovation input, the United States has proven to be world-leading in its innovation output. Despite the United States having lower ranks on infrastructure, human capital, and research and institutions, it is more efficient in its innovation, doing more with less. The United States does not have as strong an innovation framework as other nations — outside of market sophistication, where it ranks first — yet it continues to produce leading innovation nonetheless.

With more than 25 indicators where the United States is significantly ahead of Australia, Australia has considerable room for growth. In three pillars in particular — namely business sophistication, knowledge and technology outputs, and creative outputs — Australia ranks moderately to significantly below the United States. Within these three pillars, the specific sub-pillars where Australia ranks significantly below the United States are innovation linkages; knowledge absorption; trade, competition and market scale; investment; knowledge creation; knowledge impact; knowledge diffusion; creative goods and services; and online creativity.

By far the starkest contrast between the United States and Australia in all these sub-pillars is within knowledge diffusion, where the United States ranks 12th and Australia ranks 96th. The GII’s knowledge diffusion sub-pillar is made up of four indicators: intellectual property receipts as a per cent of total trade, high tech exports as a per cent of total trade, ICT services as a per cent of total trade, and FDI net outflows as a per cent of GDP.

Patent applications

The United States ranks sixth in the GII for resident patent applications filed at a national patent office, while Australia ranks 45th.

This can largely be attributed to the fact that only six per cent of Australian patents granted in 2016 were held by Australians. Only 1,433 patents were granted by IP Australia for Australian residents in 2016, but almost six times that were filed by Australians in other countries. The top three destinations of patents filed by Australians abroad were the United States (43 per cent), the European Patent Office (10 per cent), and China (7 per cent). Cost is a huge factor in the small number of Australian patents. According to Paula Chavez, an American patent lawyer now working in Australia, a US patent application costs approximately $2,000-$3,000, while the cost will be upwards of $10,000 in Australia.

Venture capital deals

The United States ranks first in the number of venture capital deals per billion dollars of GDP while Australia ranks 22nd.

In 2016, Australia’s venture capital amounted to only 0.023 per cent of its GDP, less than half the OECD average of 0.049 per cent. Compared to the United States, there is 7.3 times more US venture funding than in Australia, per capita. In 2016, 21 US venture capital funds were raised that were individually larger than the whole amount raised in the Australian market in that year. Due to the limited availability of funds, many Australians seek capital abroad, especially in the United States, as it is much easier to raise money where there is more money to be distributed. In fact, in 2016's Startup Muster, almost one quarter of Australian start-ups were looking to undertake capital raising overseas. At the same time, venture capital fundraising in Australia reached the highest level on record in FY2016, with seven funds raising a total of $568 million. Australian VC investment hit $230m in the second quarter of 2017, with the number of deals increasing from 25 to 36.

Research talent in business

The United States ranks fourth in the world in researchers in business, while Australia ranked 46th in the GII and has the lowest rate of collaboration on innovation between industry and researchers in the OECD.

The government threatens the advancement of research in Australia with its replacement of the 457-visa, making it more difficult for foreign researchers to work in Australia.

The government threatens the advancement of research in Australia with its replacement of the 457-visa, making it more difficult for foreign researchers to work in Australia. The changes include the requirement of two years of working experience, which will prevent new PhD graduates from overseas to contribute to Australian research. This will further affect university lecturers, who made up nearly 2000 of the 457 visas, as they are now in the category for the short-term, two-year visa.

Business expenditures on R&D

While much of the data in the GII is country-focused, some of the data is available at a state level in both the United States and Australia. This enables a comparison of US and Australian states. One remarkable comparison is business expenditures on research and development (BERD) as a per cent of gross state product. Although Australia is ranked 16th on this indicator and only trails the United States (at 10th place) by a small margin, a closer look at state-level data shows greater discrepancies. New South Wales, the Australian state that spends more on R&D than any other (both in sheer size and as a percentage of gross state product) is ranked 26th overall when combining US states and Australian states into a comparison list. As a percentage of gross state product, New South Wales spends less on research and development than the US states of Idaho, Kansas, and New Hampshire.

Labour markets

While any standard comparison of nations will be the subject of debate, some measurements are more controversial than others. One such controversial indicator in the GII is the cost of redundancy dismissal, which measures the “notice period and severance pay for redundancy dismissal (in salary weeks, averages for workers with one, five, and 10 years of tenure, with a minimum threshold of eight weeks)”.

Australia ranks 43rd overall in this category while the United States is tied for first along with 19 other nations. While in most indicators, countries would like to be ranked first, this is one instance where Australia may prefer to have a lower rank. Ultimately, less notice and mandatory severance pay can instigate a social instability that some nations would prefer avoiding.

Areas for future research

Geographically-clustered research

While the GII focuses on innovation at a nation-wide level, there is growing consensus amongst innovation researchers that innovative activity is often concentrated in geographic clusters — such as the San Francisco Bay Area and Boston. Until the 2017 iteration of the GII, however, the innovative nature of these clusters wasn't quantified.

The GII’s first attempt at ranking them is done purely by number of Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) filings. Tokyo-Yokohama and Shenzhen-Hong Kong are, respectively, ranked first and second, with San Jose-San Francisco ranked third. The only Australian regions within the 100 listed clusters are Sydney, which ranks 44th in the world, and Melbourne, which ranks 60th.

Ability to attract skilled migrants

Innovative firms around the world are all in competition with each other to attract the best and brightest, particularly the best and brightest among those with STEM skills. Australia has benefited enormously from its family-friendly lifestyle — attracting and keeping skilled individuals who have gone on to make innovative contributions impacting the world. While stability, exam scores and safety are all important indicators, they do not reflect livability — a key attraction for innovators in Australia. Australian cities are some of the most livable in the world. Melbourne consistently ranks as the world’s most livable city, according to the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Livability Index which ranks 140 cities each year. Adelaide and Perth also rank in the top 10, with top scores on healthcare, education and infrastructure. Sydney is 11th and all five major state capitals rank in the top 20. A quantifiable livability indicator would enrich the GII.

Interactive: State by state comparison

A number of indicators making up the Global Innovation Index have data available at a state level, enabling a comparison of Australian states with US states (see interactive figure and table below).

Education data comparison

Comparing average exam results across reading, scientific and mathematical proficiency gives an insight into how Australian states compare with each other, and with US states.

PISA proficiency scores are used for Australia and NAEP scores for the United States. Both provide a common metric at a state level and test proficiency.

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (OECD) Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) only allows for comparison at a national level between Australia and the United States. Australian PISA scores are higher than US scores and above the OECD average across science, mathematics and reading. PISA scores for both Australia and the United States have been declining over the last three testing cycles (a six year period covering 2009, 2012 and 2015).

R&D spending comparison

Comparing business spending on research and development (R&D) as a percentage of gross state product gives an insight into the investment made by businesses in one of the key drivers of innovation. While many US innovations have been spurred by US government spending, particularly Department of Defense spending, the state data makes clear that the private sector in most US states spend a larger proportion of their gross state product on R&D than Australian states.

The US states of California and Massachusetts in particular stand out for their business spending on R&D — with proportional amounts around three times the size of Australia’s top state, New South Wales — but businesses in some US states stand out for less known reasons. In Delaware, for example, businesses may not necessarily be conducting more R&D — instead, many businesses located throughout the country list the small state as a headquarters for tax considerations.

Technology exports by state comparison

Comparing technology exports by state gives an insight into how critical technology is in a state’s economy. Based on the top 20 exports of each state in the United States and Australia, the data shows both the value of tech exports in 2015 as well as what percentage of total state exports are tech exports. For states that do not have a technology export amongst their top 20 exports, N/A is written.

In terms of percentage of exports that are technology-related, the District of Columbia – or Washington DC – stands out at more than 80 per cent largely because the city-state is only 177 square kilometres and does not have substantial natural resources.

Hover over each state to see the actual figures.

View the spatial data in tabular form by clicking on the dropdown menu below.

Policy recommendations

Incentivise venture capital

Australia is famously resource rich and capital poor. While innovative ideas come out of Australia, the lack of domestic capital restricts the ability to grow such ideas into major businesses. Many of Australia’s best and brightest companies and entrepreneurs end up moving to Silicon Valley, where the capital and networks they need to grow their firms is available. If Australian governments want ambitious firms to not only be created in Australia but to stay and grow in Australia too, they will need to incentivise venture capital firms (VCs), most of whom will be from the United States, to establish offices in Australia.

If Australian governments want ambitious firms to not only be created in Australia but to stay and grow in Australia too, they will need to incentivise venture capital firms to establish offices in Australia.

Government incentives for VCs is obviously not an easy policy to implement in an increasingly populist political climate. Yet one need only to look at Israel to see how effective such policies can be. Once lacking in VCs, the Israeli government established the Yozma program in 1993, which provided equity guarantees and tax breaks primarily for US VCs. Today, the program’s incentives have largely been phased out but Israel, now known as the “start-up nation”, has a higher rate of venture capital as a share of GDP than any other OECD country.

Welcome skilled immigrants

One of the primary reasons the United States has been able to maintain its innovative edge for so long is the fact that it has, for the most part, maintained an immigration system that has welcomed the likes of Elon Musk of Tesla and SpaceX, Sergey Brin of Google, and Andy Grove of Intel. More than 1,400 economists agreed that immigrants in the United States are significantly more likely to work in innovative STEM fields that “create life-improving products and drive economic growth”.

Australia has taken steps recently to limit skills-based business visas. Known throughout the world for its exceptional lifestyle, Australia can more easily attract highly-skilled migrants than almost any other country in the region. However, Australia should look to Canada’s Global Skills Strategy, which has the purpose of making it easier for Canadian businesses to attract the talent they need to succeed in the global marketplace. Canada is welcoming international talent, particularly in "global talent occupations" recognised as being in short supply. In doing so, Canadian firms can scale-up and grow, creating additional jobs. High-skilled work permits can be processed in two weeks.

Welcome anchor firms

Research into the formation of innovation hubs has found that “anchor companies” play a critical role. Countless start-ups around the world have been founded by former employees of major companies like Microsoft, Intel and Google. These firms allow for critical skills and talent transfers into new localities, but they also often provide mentorship and actively support the fostering of a robust start-up environment. Policymakers should understand that anchor companies provide a level of stability and experience that innovative start-ups can benefit from.

Moving beyond STEM in school

According to Amazon Web Services (AWS), the cloud-hosting platform responsible for up to a third of the world’s internet traffic, there are currently more than 5,000 unfilled job openings in Australia requiring AWS certification, while another 50,000 such job openings are expected in the next few years. There simply are not enough qualified technology workers in Australia to satisfy the demand for them.

There is a large existing workforce facing potential significant disruption over the next decade, meaning governments and industry alike need to be thinking about and planning for worker retraining.

With the national digital technologies curriculum, Australia now has the foundation in place for a future workforce with skills in computational thinking, data collection, interpretation and transformation, digital systems use and systems thinking. From Foundation year (e.g. kindergarten), and throughout their school life, all Australian students learn the concepts to enable them to write code. However, there is a large existing workforce facing potential significant disruption over the next decade, meaning governments and industry alike need to be thinking about and planning for worker retraining.

Increase international awareness of Australia’s innovative capabilities

In the United States, there is little awareness of Australia’s innovative capabilities, including in regions that are aggressively looking for more innovative talent, such as Silicon Valley, Boston, and New York.

This lack of awareness could be ameliorated with a public campaign by the Australian government in these regions that highlights Australia’s many strengths, such as less expensive engineers and a world-leading tech adoption rate. These innovative capabilities, when combined with the fact that Australia is one of the most livable countries in the world (public health care, affordable yet highly-ranked universities, and great weather), would surely help to draw the sort of innovative talent that Australia is looking to attract.

FAQs and methodology

What is innovation?

Innovation is defined by the OECD as “the implementation of a new or significantly improved product (good or service), process, new marketing method or a new organisational method in business practices, workplace organisation or external relations”. Broadly, innovation enables doing things differently, as well as doing different things. It turns ideas into opportunity.

Why is innovation important?

Innovation drives business competitiveness, new business growth, new jobs, and is a key driver of economic growth. The OECD attributes approximately 50 per cent of member countries long term economic growth to innovation.

In terms of its relevance to Australia, innovation will determine the country’s future. With more than a quarter century of continued economic growth following deregulation in the 1980s and 1990s, and a mining boom through much of the 2000s and 2010s, Australia now enjoys high wage standards and standards of living, as well as a strong social safety net. In order to maintain its lifestyle, however, Australia must find ways to innovate.

What is the Global Innovation Index (GII) and why should we use it?

Produced jointly by Cornell University, INSEAD business school and the World Intellectual Property Organisation, the Global Innovation Index assesses the innovation performance of 127 countries and economies around the world based on 81 indicators. It is the most authoritative and comprehensive resource for quantifying innovation amongst nations. It also clearly articulates what Australia does well and what Australia could do better in when it comes to innovation.

Why compare Australia and America?

The United States may be ranked as the fourth most innovative country in the world, but it remains the number one destination for the output of Australia’s innovation — and much of the world’s, for that matter. The obituary for the loss of America’s innovative supremacy has been written many times, but this data, along with other research, make it clear that such sentiment is still premature. Although many have proclaimed this to be the Asian Century, the United States still attracts the best and brightest minds for innovation, from Australia and the rest of the world.

Furthermore, as a close ally in economic, military, intelligence, and diplomatic spheres, it makes sense to analyse the differences in order to see what Australia does well compared to the United States and what Australia could perhaps learn from the United States.

What does innovation actually look like?

There are four broad categories of innovation:

- Product innovation: The introduction of a good or service that is new or significantly improved with respect to its characteristics or intended uses. This includes significant improvements in technical specifications, components, materials, incorporated software, user friendliness or other functional characteristics.

Example: The original iPhone. - Process innovation: The implementation of a new or significantly improved production or delivery method. This includes significant changes in techniques, equipment and/or software.

Example: Moving from manual spreadsheet business accounts management to cloud-based accounting software like Xero. - Marketing innovation: The implementation of a new marketing method involving significant changes in product design or packaging, product placement, product promotion or pricing.

Example: Introduction of bundling for telecommunications companies in the 2000s or the introduction of product placement in television shows, like Masterchef. - Organisational innovation: The implementation of a new organisational method in business practices, workplace organisation or external relations.

Example: A restructure that changes the organisational structure from product silos to customer segments, or to a matrix organisation.

Methodology

The data in this report comes from the Global Innovation Index (2010 to 2017). The data was processed in R. All data visualisations were created in D3.js. All code used to create the data visualisations can be found on the USSC's GitHub page.

Your feedback

This is an ongoing project that will continue to be expanded upon. Please email Jared Mondschein with comments, at: jared.mondschein@sydney.edu.au.

The authors are grateful for the research assistance of Innovation and Entrepreneurship Program interns Katie Schmidt and Elodie Lemesre.