President Donald Trump has hinted at a more muscular US foreign policy in the Asia-Pacific. In tweets and speeches since the election, he has adopted a hard-line on China’s island-building in the South China Sea, vowed to prevent North Korea from acquiring a functional nuclear missile, condemned Beijing over its unfair trade practices, and raised the prospect of deeper US-Taiwan relations.

His Asia team is shaping up to reflect Trump’s hawkish stance towards China on trade and security. But it is also likely to be an eclectic group whose perspectives on other Asia policy issues differ both internally and with figures on the national security cabinet. Australia will have to prepare for a more turbulent US-China relationship, as well as greater uncertainty in Washington’s Asia policy.

What’s the Asia team?

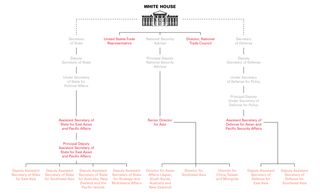

A president’s Asia team refers to the constellation of officials appointed to key positions in the US foreign policy bureaucracy responsible for designing and coordinating Asia policy. This loose grouping of approximately a dozen individuals cuts across agencies and is not organised in a hierarchical way. It revolves around three appointments:

- Senior Director for Asia at the National Security Council (NSC): responsible, under the National Security Advisor, for coordinating interagency implementation of security policy in Indo-Pacific Asia, and developing strategic options and advice for the president.1

- Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs: the leading State Department official for foreign policy in the Asia-Pacific — including major bilateral relationships, US alliances, regional organisations, and South China Sea policy — responsible for advising the department’s senior leadership and formulating policy with them.

- Assistant Secretary of Defense for Asian and Pacific Security Affairs: the leading Pentagon official for security and defence policy in the Indo-Pacific — including force posture, planning, and cooperation with military partners — responsible for advising its senior leadership, and developing and implementing regional defence policy.

Trade officials are not generally considered part of the Asia team. But given Trump’s focus on improving the terms of US trade relationships, they will have an outsized impact on this administration’s Asia policy, particularly towards China. Two appointments will be influential:

- United States Trade Representative (USTR): responsible for leading negotiations on trade agreements and disputes with foreign governments, representing the US in global trade organisations, and providing advice to the president on trade issues such as what positions Washington should adopt on trade deals.

- Director of the National Trade Council: a new position and office announced by Trump that will “advise the president on innovative strategies in trade negotiations” and “coordinate with other agencies” on trade initiatives, such as the “Buy America, Hire America” program.2

As in past administrations, the individuals occupying these positions will represent different and, at times, competing inputs into Asia policy. The balance of influence across these roles will vary according to who is appointed and the presidential priorities of the moment.3

Trump’s Asia team in the making

Reflecting President Trump’s prioritisation of economic issues over security policy in Asia, trade nominees have led the way on Asia team appointments. Vocal protectionist and China critic Robert Lighthizer will become the United States Trade Representative, and is poised to advance Trump’s “America first” trade policy in the Asia-Pacific. As a deputy USTR in the Ronald Regan Administration, Lighthizer imposed tough trade restrictions on countries, like Japan, for dumping in US markets; and has since represented US firms in their effort to minimise foreign competition.4 Lighthizer’s condemnation of Republicans in 2008 for “embrac[ing] unbridled free trade… no matter how many jobs are lost, [or] how high the trade deficit rises” aligns with Trump’s agenda to bring back jobs by ending bad deals.5 Like Trump, Lighthizer sees “Chinese mercantilism” and the relocation of US firms to China as the main driver of the United States’ trade imbalance. He advocates “aggressive trade measures” to combat the deficit, including tariffs and a possible abrogation of US commitments under the World Trade Organisation.6

An even more outspoken China hawk, Peter Navarro, will serve as director of the National Trade Council. Arguably Trump’s closest China advisor throughout the election campaign, the Harvard-trained economist espouses radical views about the dangers of free-trade with China, describing it as a “zero sum game” that erodes “prosperity in the global economy”.7 Navarro blames China’s unfair trade practices — such as currency manipulation, poor work standards, environmental damage, and intellectual property theft — for the loss of US manufacturing jobs and the trade imbalance.8 His solution, like Trump’s, is a 43 per cent tariff on Chinese imports.9 Navarro has also called for tougher US push-back on “China’s militarism” — advocating a 350 ship navy, strong regional alliances, and support for Taiwan on democratic and strategic grounds.10 He will likely have the president’s ear, at least on trade policy with China, and lobby for a muscular approach to broader US-China issues.

On the security policy side of Trump’s Asia team, the only sure candidate is Matt Pottinger, who will be the NSC’s senior director for Asia. Notwithstanding his close relationship with Trump’s national security advisor, Lt. Gen. Michael Flynn, the former US Marine is an unusual choice.11 Unlike his predecessors, Pottinger has never held a government position and has no background on Asia-Pacific security policy.12 Nor does he have established relationships with many Asia policy officials in the US and abroad. But Pottinger might bring unconventional qualifications to his role. Originally trained as a Mandarin linguist, he spent seven years as a journalist in China — an experience that has given him an inside-out perspective on the country’s challenges and opportunities.13 Likewise, after joining the Marines Pottinger gained valuable operational experience in military intelligence and demonstrated in a major report on US intelligence failure in Afghanistan — co-authored with Flynn — his ability to design sweeping changes to institutionalised operating procedures.14 These skills could make him an effective change-maker on Asia policy coordination.

Navarro has called for tougher US push-back on “China’s militarism” — advocating a 350 ship navy, strong regional alliances, and support for Taiwan on democratic and strategic grounds.

While little is known about Pottinger’s worldview, his writing suggests that he will adopt a sceptical and values-based stance towards Beijing. In 2005, Pottinger explained that living in China had taught him “what a non-democratic country can do to its citizens”, recalling the surveillance and state violence that he and others endured. This led him to appreciate “the institutions that distinguish the US” — such as “the separation of powers, a free press, and the right to vote” — and played into his decision to join the Marines.15 Pottinger was scathing of China in a 2007 letter in which he criticised the government’s “little respect for the truth” and imposed “self-censorship” of the media.16 These sentiments will chime with the hawkish line on China held by Navarro and others in Trump’s Asia team.

As Trump’s secretaries of state and defense are not Asia experts, their assistant secretaries are likely to be influential. Two accomplished Asia hands are under serious consideration.17 Former George W. Bush administration official, Randall Schriver, is the frontrunner for the defence position. He views Beijing as a strategic competitor, and is suspicious of its military modernisation, revisionist aims, and “backsliding” on democracy and human rights.18 Schriver is likely to push for an enhanced military rebalance to Asia — seeking a more muscular US forward presence and asking allies, like Australia and Japan, to contribute more to collective defence. As a leading advocate of deepening US-Taiwan defence relations, Schriver would support Trump’s engagement of Taipei provided it is not simply a bargaining chip with China.19

The other frontrunner for an assistant secretary role is Victor Cha, another Bush-era official and a specialist on North Korea. He is likely to be more nuanced on China than other Trump advisors. Cha views China as “America’s great power competitor in the Asia-Pacific region” and anticipates “natural friction”, but believes competition can be managed and cooperation advanced on “global issues like climate change”.20 On North Korea, he is more moderate than Trump and Secretary of State Rex Tillerson. Although Cha thinks Washington should press Beijing “to take a more responsible position” on non-proliferation, he has not called for sanctions on Chinese firms that trade with North Korea and believes Washington should engage Beijing and Pyongyang without preconditions.21 Crucially, Cha departs from their thinking on the importance of democratic progress within North Korea — calling on the US to “implement a proactive human rights agenda” because of the “symbiotic relationship between rights abuses and security”.22

Implications for Australia

Canberra should prepare for a Trump Administration that will be tough on Beijing across most aspects of trade and security policy. So far, this is greatest point of convergence within Trump’s Asia team and with his national security cabinet. Trump, Lighthizer and Navarro’s preference for a tariff on Chinese imports is likely to translate into early action, particularly in industries like steel.23 Where tariffs fall in the 10 to 45 per cent range is an open question. But tariffs would undoubtedly spark retaliatory measures by China, risking a trade war and raising production costs across the region. Were Trump to ask US allies to support a tariff regime, Canberra would face a difficult choice between saying no to the administration on one of its core priorities, or damaging Australia’s interests in free trade and stable relations with China.

On security, Trump’s Asia team and cabinet are likely to support a stronger US military presence in the Asia-Pacific — potentially raising demands on Australia to facilitate visiting forces, deepen military interoperability, or participate in actions like freedom-of-navigation operations in the South China Sea.24 It is in Australia’s interest to support the US military in safeguarding Asia’s rules-based order, provided US forces continue to play a stabilising role. Yet, whether or not specific requests are in Australia’s interests, Canberra will find it difficult to foster public support for US-Australia security cooperation under a president that 66 per cent of Australians oppose.25 This is even more true of changes to US-Taiwan relations. Given the alignment between Trump, Navarro, Schriver and possibly Pottinger on bolstering US ties with democratic Taiwan, this issue may emerge as the biggest source of friction in US-China relations. Canberra opposes moves to revise the “One China Policy” — a 1979 understanding that nations with diplomatic ties to Beijing will not support Taiwan’s independence — and could find itself at loggerheads with Washington over this issue.

By adopting tough policies against China on most major bilateral issues at once, Trump will create more, not less, volatility in US-China ties.26 This is contrary to Australia’s interest in a constructive major power relationship between its two most important foreign partners and may be destabilising for the entire region.27 Other American allies — like Japan, South Korea, and Singapore — will face the same predicament and, like Australia, could be asked by the Trump Administration to support policies that do not align with their priorities or factor in domestic sensitivities. To offset these risks, Canberra should clarify its position on issues like Taiwan, Chinese trade practices, and US basing in Australia prior to possible requests by the incoming administration. Canberra should also caucus more with likeminded US allies in Asia to ensure, where possible, that Australia is aligned with its other partners on issues of disagreement with the United States.

Canberra will have to get used to a degree of uncertainty in Washington’s Asia policy due to possible tensions both inside Trump’s Asia team and with the rest of his cabinet. While it is impossible to predict where these discrepancies will arise, three issues could stir discord within the administration. First, Tillerson and China Ambassador Terry Branstad may clash with Lighthizer, Navarro, and Trump over imposition of tariffs on China, though it appears that the protectionists are more influential at this stage.28 Second, it is possible that moderate voices on US-China relations, like Cha and Secretary of Defence James Mattis, will overrule the more provocative inclinations of the pro-Taiwan camp. Finally, there is a significant split on the issue of democratic values in foreign policy — with Navarro, Pottinger, Schriver, Cha and Mattis broadly in favour of defending ideals abroad, as opposed to Trump and Tillerson who are less comfortable with this approach. Australian officials will thus have to establish relationships with unfamiliar interlocutors that do not have deep networks in Australia to appraise the internal debates in the administration’s Asia policy.