Introduction

The novel coronavirus is first and foremost an international health disaster. A quarter of the world is under restricted conditions, if not total lockdown. Yet, sadly, this pandemic will be measured almost equally in the economic damage it wreaks as in the tragic loss of life that it will no doubt provoke in its months-long reign of terror.

COVID-19 will destroy the travel and tourism industry. The World Travel and Tourism Council estimates a decline of 13 per cent of economic input from the sector globally within a month. In February, inbound flights to some Asian cities fell by more than 75 per cent.1 The same happened globally in March.2 By April, ghost flights within the United States were flying with sole passengers on board.3 The United States Transportation Security Administration screened fewer than 130,000 air travellers on 3 April 2020, compared with 2.5 million on the same day in 2019.

The United States Transportation Security Administration screened fewer than 130,000 air travellers on 3 April 2020, compared with 2.5 million on the same day in 2019.

There are, of course, forecasts that are far more pessimistic than President Trump’s initial hopes for a resurrection by Easter weekend. There are many epidemiologists and virologists who recognise this as the devastating pandemic they have warned about for decades.4 Both health professionals and economists recognise this as a pandemic that could shutter the global economy for years and lead to another great depression.

This pandemic was caused, in part, by air transport. Just as the (erroneously named) Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918-19 was spread by the global transport of returning troops from the Great War, so too, COVID-19 was spread to all four corners of the globe by rapid travel. The most effective method was by air; infected travellers from the epicentre in the Chinese city of Wuhan on work trips to Singapore and Tehran, among other transit hubs. Of course, some of the most effective vessels of transmissions have proved to be cruise liners, whose capacity to incubate disease has long been known.

Commercial air travel is the leading edge of COVID-19 industrial impact

Commercial air transport is at the forefront of COVID-19. No industry has been hit harder or more rapidly. In February 2020, more than 20,000 cities were connected by commercial flights. In late March 2020, this had fallen to just 6,500.5

Travel bans have descended not just between countries, but in many federal countries, along state lines too.6 By early April 2020, commercial air transport had ceased to exist as a frequent means of travel in most developed countries. Domestic, as well as international flights are unviable as physical distancing measures mean no movement outside personal homes is permitted.

In a matter of weeks, the airline industry worldwide has been brought to its knees by this new coronavirus, with carriers slashing schedules, thousands of aircraft grounded, employees put on indefinite leave, and airports devoid of passengers.

Aerospace, the industry of making aircraft has been hit hard as well. Although there is a usually a four- to six-month lag between dips in airline fortunes and those of the airframers, Boeing and Airbus have both been eyeing up government bailouts since mid-March. Their teams of economists know just how catastrophic this pandemic will be, even if some are still talking of 15-day crises and temporary blips.

Australia’s dramatically smaller aerospace industry has seen subcontracts dry up as backlogs disappeared overnight following the scramble by global airlines to cancel aircraft orders planned into 2024.

In Australia, Rex Regional Express has entered a trading halt and Virgin Australia has announced mass redundancies. Qantas Airways, with slightly more time up its sleeves, has been redeploying staff and grounding flights while taking up its case with government, hoping the extent of its workforce, the reliance by government on its services and its national carrier and challenger status will hold it in good stead.

The United States commercial air industry is already teetering on the edge

Looking at the United States, the highly interwoven air transport industry already appears to be fraying at the seams. In the week to 18 March 2020, US airlines said they needed US$50 billion to survive, United Airlines grounded half its fleet, WestJet suspended its international operations. US regional carriers Compass Airlines and Trans States Airlines were the first US carriers to announce plans to cease operations in early April. Transat and Porter Air all followed suit, while dozens of air traffic control towers are now closed due to staff testing positive for the virus.7

The knock-on effect is that despite Boeing’s request for a US$60 billion bailout for the entire aerospace industry (which led to former US Ambassador to the United Nations Nikki Haley resigning from the Boeing board in protest at state aid), aerospace manufacturers have already started hitting the wall. Boeing, which has major operations in one of the COVID-19 hotspots of Seattle, Washington, has closed its assembly lines until further notice. Smaller US firms, like Longview Aerospace have also announced they will suspend production of Bombardier Dash-8 Q400s and de Havilland DC-8 Twin Otters.

So what does this mean for the future of air travel? The plain answer is that its future is in grave doubt.

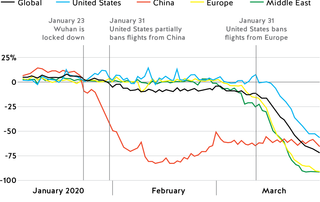

Figure 1. Change in the number of flights tracked compared to the same day a year earlier

The United States, responsible for some 37 per cent of all air traffic across the globe, is in lockdown in most states.8 Pandemic is not covered by most insurance policies for businesses, leaving many employers to push the envelope, potentially exposing many more to the virus.9 The United States is not alone in its slow response, other countries like Australia and the UK have lagged behind economies such as Taiwan and Singapore in flattening the infection curve.

Many of the world’s southern states, especially those in South America — on whose economy the United States is interlinked — have neither the resolve (in the case of Brazil) nor the fiscal space to invoke the massive public intervention required to halt the spread.

What’s next?

The current estimate as to how much the airline industry will lose this year has been published by the International Air Transport Association.10 It points to around US$250 billion in lost income for the year. This would see 2020 some 45 per cent down on 2019, assuming the travel restrictions ease by the middle of the year.

In Europe, most low-cost airlines are grounded until May, with airports also closed. In the United States, meanwhile, some US$40 billion of the US$2 trillion federal government bailout is earmarked for airlines, to cover their operations just until the end of April.

That assumes the peak is in April.

But if, as some epidemiologists suggest, that the peak is more likely to be July, August or October in the United States, then a far different scenario will emerge. The World Trade Organization rules on state aid to airlines will come under test, as more and more comprehensive bailouts and nationalisation programs take hold.

For now, airlines will focus on flying in medical supplies and aerospace manufacturers can convert some of their facilities to produce ventilators. This will provide short-term meaning to their employees and communities. But longer-term, things look dire for the global air transport industry.

Likely trends and potential scenarios

Should border shutdowns proliferate and air travel effectively be banned until the end of 2020, the global air transport system will collapse. This is clearly the worst-case scenario and there are other, less severe potential endgames for the air industry, governments and passengers.

1. How the air industry may respond

Onboard social distancing once business resumes. For commercial flights, this may mean leaving the middle seat free in economy. For those with access to business jets, there will likely be a boost in private aviation as the super-rich exercise social distancing via executive jets whisking them and their families between meetings, with little risk of exposure to COVID-19. Although private aviation is currently down some 75 per cent, due to movement bans, the National Business Aviation Association predicts an upswing from those needing to access remote airports.11

A rise in cargo operations from all commercial airlines offsetting lost passenger traffic, leading to a price war that could undercut sea freight. Coupled with the boost in home delivery, express package couriers like DHL, FedEx and UPS will face competition from postal services using national carrier’s belly freight holds. The Australian Government, for example, released a A$110 million International Freight Assistance Mechanism to assist Australia’s agricultural and fisheries export by subsidising flights.12

An end to thinner routes and a return to hub-and-spoke operations. During the early 21st century, airlines globally used 300-seater aircraft such as the Boeing 787 Dreamliner and the Airbus A350 to open up new city pairs, linking secondary cities with secondary city, bypassing the hubs. After COVID-19, however, with a severe curtailment to international routes, only the thickest (also known as trunk routes) will survive. The Boeing 787 Dreamliner and the Airbus A350, while essential in a few years’ time, will be furloughed as the far larger Boeing 747 jumbo jet and Airbus A380 superjumbo continue to ply the long-distance, high-capacity air routes that remain.

The focus on synthetic fuels and alternate propulsion to ease as airlines scramble for survival. With biofuel costing at least five times more that of traditional ‘jet A fuel’, airlines will be asking for extensions in their environmental pledges.

The tumbling of airline CEOs’ salaries. The US aviation assistance package, some US$78 billion of the US$2 trillion, is for loans and payroll support for airlines and aviation industry workers. However, in a portent of a correction, executive pay, stock buybacks and dividend restrictions are all in place to ensure the money flows to maintain employee levels, rather than reward the highly paid C-suite.

The proliferation of novel start-ups beginning in 2021. The availability of low-interest credit, combined with a glut in pre-owned aircraft becoming available at discounted costs will allow for a third wave of budget carriers.

2. How the government may respond

The government takeover of privately-owned national carriers, reversing 40 years of liberalisation. While less likely in the United States, the national ownership provisions of the Chicago Convention seem comforting right now. The ability of national governments to protect air routes into their territories, while loosened over decades, provided some cover after 9/11, with bankruptcies limited to Belgian national carrier Sabena and Swissair in Europe. US carriers were able to enter bankruptcy protection.

Increased state intervention in airline activities. This may be operational, but more likely to be in the form of tied bailouts or conditional restructuring loans. Either way, expect government around the world, even the United States, to start specifying what they expect to extract for their interventions. These conditions may be counter to what an unchained business community would ordinarily want, but a necessity in these unchartered times.

A government intervention of filling planes with government employees in order to restore connectivity between cities as part of recovery efforts. More likely are generous bailout packages that expand airline route subsidies like the US Essential Air Services scheme, or the Regulated Routes program in Australia. These schemes are funded by federal or state governments to underwrite air routes that in theory would not be economically viable without government support, in order to provide economic linkages. The US scheme, designed in the 1970s, is often regarded as part of the pork barrelling armoury of senators and congressmen, who deliver cheaper air travel subsidies to their communities. The Australian schemes, largely delivered by the states, are also useful in supporting regional communities, albeit less overtly politically.

A new virology status is demanded between countries. Akin to yellow fever certificates — a certificate proving that an individual has received a yellow fever vaccination — travel will only be possible between countries declared COVID-free for at least 40 days. Once air travel resumes, it will be only between those territories declared virus-free.

More checkpoints at many more points in the journey. As with previous epidemics, such as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), heat sensors will be a part of airport protocol. More onerous will be itinerary disclosures that will allow local and national health authorities to track arrivals’ movements. This may not be Chinese-style electronic tracking, but rather a handing over of travel agency data to authorities.

The waiving of departure taxes, fuel taxes and visa fees — all designed to recoup costs borne by government for air travel — waived in an attempt to stimulate growth. For those able to fly, there will likely be some very attractive fares in the market for 2021.

3. How airline customers may respond

Corporates become reluctant bookers of air travel even once routes re-open. The duty of care provisions will bar most employers from allowing staff to travel to COVID-19 affected territories. This will have knock-on effects for high-value forward bookings for airlines. For example, if a company’s health insurance provision prohibits placing that employee in danger for health reasons, that is likely to include unsanitised hotels, certain destinations and even airlines that do not comply. The compliance industry conversely will be bolstered as corporates will seek assurance from an accreditation body that the accommodation and transport options chosen by their employees are safe and clean. In the United States, with health insurance provided by employers, the last thing they want is employees exposed to new COVID-19 infections.

Premium economy seating spaces become the norm, albeit at a higher cost. As physical spacing rules become commonplace, passengers will request greater seat pitch once they resume flying. More legroom, even if the tradeoff is less frequent flying, could be a feature of mid-2020’s air transport.