Introduction

During the 2016 presidential campaign, Donald Trump complained that the United States’ “military is a disaster” and promised to make it “so big, so powerful, so strong that nobody – absolutely nobody – is gonna mess with us”.1 So far the president has not delivered on his rhetoric. Although Trump has requested additional funding for defence, the magnitude of the increase falls well short of his promises. Republican defence hawks are advocating for additional resources above the president’s request. But a combination of ongoing spending caps imposed by the Budget Control Act (BCA) and political gridlock in Washington will prevent Congress from passing more than a modest increase in defence spending for 2018.

Washington’s inability to return the defence budget to pre-BCA levels is having a serious impact on America’s global strategic presence. As Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Joseph Dunford warned in June: “Without sustained, sufficient, and predictable funding, I assess that within five years we will lose our ability to project power; the basis of how we defend the homeland, advance US interests, and meet our alliance commitments.”2 His comment was more than a bureaucratic bid for extra funding. Ongoing conflicts in the Middle East and growing operational demands in Europe and Asia are taxing the military’s ability to procure, train, repair, and deploy its forces at sustainable levels. The US military cannot continue to modernise and fix these “military readiness” problems without greater political certainty and a commitment to higher spending.

While there is no solution in sight to the defence budget crisis, there are signs that America’s strategic presence in Indo-Pacific Asia will be prioritised in this budget cycle. Congress has emphasised the need to strengthen regional capabilities in response to Chinese and North Korean challenges, including by increasing cooperation with allies and bolstering extended deterrence. Like the White House, Congress is allocating resources to some readiness issues – though not at levels that will satisfy the Pentagon – as well as supporting advancements in space, cyber, electronic warfare, and ballistic missile systems. Australia should welcome this sustained military engagement in the Indo-Pacific, but remain cautious about Washington’s ability to reverse the impact of budget uncertainty on the American armed forces.

Congress and the defence budget

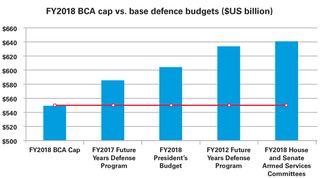

Although the president and Department of Defense make a budget request, it is Congress that ultimately determines total annual expenditure on national defence, and makes minor but nonetheless significant changes to the substance of the defence budget.3 The current chairmen of the Senate and House Armed Services Committees, and some Democrats, are pushing for significantly higher military spending than the White House. The President’s Budget request (PB), released by budget director Mick Mulvaney in May, requests a total of $667.6 billion in discretionary national defence funding for the 2018 fiscal year (FY), including $639.1 billion for the Department of Defense (DoD).4 Although the White House touted this as a major increase of $25 billion, defence budget analysts and key congressional Republicans regard it as insufficient—noting the topline is only three per cent higher than was projected in President Barack Obama’s final budget. 5 According to Katherine Blakeley, a nonpartisan budget analyst, national security is “an afterthought in the FY 2018 President’s Budget request, playing fourth fiddle to tax cuts, cutting non-defence discretionary spending by 30 per cent over a decade… and balancing the federal budget within ten years.”6

By contrast, the Armed Services Committees are pursuing a defence budget topline that is approximately $30 billion more than President Trump’s request. In light of the military’s declining capacity to train, maintain, and deploy forces abroad at levels the Pentagon deems sustainable, there is an emerging bipartisan consensus in Congress that the base defence budget should rise – or else a mismatch will emerge between US objectives and capabilities. The chairmen of the Senate and House Armed Services Committees, John McCain and Mac Thornberry, are driving this agenda.7 In July, the House has passed a National Defense Authorisation Act of $696 billion, while the Senate’s version of this bill totalled $700 billion and was passed on 18 September. The final defence budget, however, is the product of difficult compromises, and there are significant currents working against higher spending.

Defence budget factions in the 115th US Congress

- 'Republican defence hawks’, led by Senator McCain and Representative Thornberry, are the most prominent advocates for increased defence spending, driven by concerns over the state of the US military and a desire to repeal the BCA. Compared to other Republican groups, defence hawks are less preoccupied with domestic spending relative to defence spending.

- ‘Mainstream Republicans’ represent the centre of gravity in the Congressional Republican Party. Like defence hawks, they have proposed – and voted for in the House – a defence budget far higher than President Trump’s request. But mainstream Republicans also want to reduce discretionary non-defence spending. Its members will be hesitant to vote for a major increase in defence spending if the political price tag is a commensurate increase in non-defence spending.

- ‘Republican fiscal hawks’ are mostly members of the far-right House Freedom Caucus, which seeks to reduce the size of the government through spending cuts.8 Fiscal hawks are a larger portion of House Republicans than Senate Republicans, but have lost traction within the Republican Party to defence hawks in recent years. The overwhelming majority of Republicans in the 115th Congress are mainstream Republicans or defence hawks.

- ‘Pro-defence Democrats’ are few in number, but comprise arguably the most important faction in this budget cycle. Their votes will be critical in any bipartisan attempt to repeal the BCA caps. Like their Republican defence hawk counterparts, pro-defence Democrats believe that BCA caps on all government spending should be increased or eliminated, because they pose unacceptable risks to the military.9 Senator Jack Reed and Representative Adam Smith, the ranking Democrats on the Armed Services Committees, are the leaders of this group.

- ‘Mainstream Democrats’ are more ambivalent about the defence budget. Most support higher spending and want to appear strong on defence. But when it comes to a vote, they typically link defence spending increases to securing additional funds for health, education, and other domestic political priorities.10 They also oppose the Trump administration’s proposal to cut funding from the State Department and USAID to pay for defence. Still, many Democrats have a vested interest in maintaining or increasing spending on major job-creating military facilities in their state or district.11

- ‘Progressive Democrats’ are primarily concerned with non-defence domestic issues and oppose increased defence spending. Senator Bernie Sanders, reflecting the sentiment of this group, said this year: “at a time when nearly half of children live near the poverty line, when millions of people are without healthcare, when our infrastructure is crumbling – should we really be investing in pouring more money into the military industrial complex?... I think not.”12 During debates over military spending, progressive Democrats more actively invoke domestic issues than their colleagues at the centre of the Democratic Party.13

Constraints on increased defence spending

Congress faces two serious obstacles to increasing defence spending: the Budget Control Act and political gridlock among six factions with competing views on how to prioritise defence against discretionary non-defence domestic spending. The BCA, introduced in 2011, imposes hard limits on defence and non-defence discretionary spending through 2021, or until Congress repeals or amends the caps. It applies to the Pentagon’s regular expenditure – often known as the “base budget” – but not the “overseas contingency operations” (OCO) account, intended as top-up funding for current deployments. More than 80 per cent of the total defence budget comes from the base budget, which is capped at $549 billion for the FY 2018, starting on 1 October. Although BCA caps have been lifted three times before – between FY 2013 and 2017 – these increases were only in the vicinity of $10-$20 billion. This is far from the level currently required to satisfy congressional defence hawks or the Pentagon.

Both the President’s Budget and House defence budget proposal exceed the $549 billion BCA base budget cap, by $54 billion and $72 billion respectively. The BCA does not impose limits on OCO expenditure, which was approximately $60 billion last year and funded deployments in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, and Europe.14 A substantial increase in OCO funding could be used to siphon funds to other defence priorities; but this is not its purpose and would require difficult compromises in the Senate. Any negotiations over a defence budget exceeding the $549 billion BCA cap are redundant until Congress decides whether the caps will be lifted. In the unlikely event that President Trump signs off on a cap-busting budget before a BCA deal, a process of budget “sequestration” would take effect – triggering a 13 per cent across-the-board cut to all defence accounts, except personnel costs, and bringing expenditure within BCA levels. In short, absent a deal in Congress, the president cannot raise the base defence budget above the BCA caps.

In this political climate, the most likely outcome is a compromise between Republicans and Democrats that includes a small increase for defence and no cuts to non-defence spending.

Political divisions within Congress will make it extremely difficult to lift the BCA caps by a substantial amount. Any move to amend the BCA requires 60 votes in the Senate, which, in practice, requires the support of most, if not all, Senate Republicans and at least eight Democrats. Given the divergent priorities among congressional factions, this is a tall order. Senate Democrats, for instance, have consistently demanded parallel increases for defence and non-defence spending, which most Republicans are unwilling to grant at high levels. A key question for the FY 2018 budget will be what concessions Republicans offer in non-defence spending to entice Democrats to support proposed defence increases. This is a delicate political balancing act. Significant increases in non-defence spending would cause many Republican fiscal conservatives to withdraw their support, meaning that even more Democrats would need to be recruited. In this political climate, the most likely outcome is a compromise between Republicans and Democrats that includes a small increase for defence and no cuts to non-defence spending.15

Strategic priorities in Congress

While Congress is wrangling over the size of President Trump’s first defence budget, it is also using the tools at its disposal to indicate strategic preferences and set some defence priorities. Together with the President’s Budget, the 2018 National Defense Authorisation Acts (NDAAs) drafted by the Senate and House Armed Services Committees suggest four strategic priorities.

Ongoing focus on Asia

Strengthening US military presence in Indo-Pacific Asia remains a top priority for Congress’ Armed Services Committees. The chairmen of these committees have released White Papers highlighting the need for additional resources to respond to Chinese military modernisation and North Korea’s nuclear program.16 Most significantly, Senator McCain has proposed an Asia-Pacific Stability Initiative which, if implemented, would deliver $7.5 billion over five years to supporting military readiness in Asia, building munitions stockpiles, and funding additional exercises and strategic infrastructure.17 Representative Thornberry has released a similar proposal to “strengthen security in the Indo-Asia-Pacific,” outlining $2.1 billion for the 2018 financial year.18 These bills are designed to transfer existing resources towards Asia-related priorities. As such, they are an important signal of Congress’ commitment to Asian allies in the face of emerging threats to the regional rules-based order and amid uncertainty about the Trump administration’s Asia policy.

The House 2018 NDAA places considerable emphasis on American strategic priorities in the Indo-Pacific region.19 Compared with the last two House NDAAs, the 2018 version contains detailed sections on US forces, regional allies, and funding priorities for the Indo-Pacific, including dedicated sections on China, North Korea, India, Australia, trilateral cooperation with South Korea and Japan, and regional bodies such as ASEAN.20 It also requires several major reports on the region to be prepared by the Department of Defense for Congress, including: an assessment on the future of US strategy and force posture in the region, a plan for strengthening extended deterrence in the region, and a report on China’s influence in the Indo-Pacific.21

Strengthening US military presence in Indo-Pacific Asia remains a top priority for Congress’ Armed Services Committees.

Improving military readiness

When addressing congressional leaders about the Pentagon’s FY 2018 budget priorities in June, Secretary of Defense James Mattis listed building military readiness as the main goal, followed by investing in advanced capabilities.22 There is a broad consensus between the Pentagon and congressional leaders that addressing military readiness – America’s ability to prepare, deploy, and sustain existing forces abroad – is an immediate and urgent budget priority. Thornberry and other Republican defence hawks have repeatedly stressed that “the current readiness crisis is the consequence of years of budget cuts and neglect”, while many mainstream Democrats agree defence cuts have been overly severe.23 As a sign of growing congressional oversight on this issue, the House 2018 NDAA requests three reports from the Pentagon in the next financial year on readiness issues, including quarterly reports on personnel, unit, and cyber shortfalls.

The Senate and House NDAAs have also allocated funding to a large number of “unfunded priorities” – items the US military has requested, but which have not been provided for in the President’s Budget. These include procurement of new equipment, additional munitions, and funds for personnel and training activities. For example, the House NDAA includes a further $88.3 million on top of the president’s request to improve training for Army units above the brigade level, $1.26 billion for “space based sustainment and readiness shortfalls”, and $57.5 million for “cyber security readiness shortfalls” in global and early warning systems for the Air Force, among others.24 Similarly, the Senate lists addressing readiness shortfalls to justify its expenditure above the President’s Budget, including an additional $1.1 million for Army strategic mobility, $8.9 million in “airmen readiness training,” and $146 million in “installation readiness” for the Air Force.25 While the administration’s budget prioritised military readiness, the Senate and House versions make it clear that there are still important shortfalls that remain unfunded.

Space, electronic warfare, and cyber capabilities

Congress has sharpened its focus on space policy and the increasingly integrated domains of electronic, space, and cyber warfare in the 2018 budget cycle. The most significant proposal is from the House Armed Service Committee for establishing a dedicated Space Corps as a new military service. The congressional champions of the idea, Republican Michael Rogers and Democrat Jim Cooper, intend the corps to be drawn from the Air Force, with a Chief of Staff that would sit on the Joint Chiefs. While the idea is not new, it is the first time that it has passed a vote in the House NDAA with bipartisan support.26 The Space Corps will not necessarily be included in the final budget, but is a key example of both chambers’ concern about the military’s ongoing superiority in future warfare domains.

Relatedly, the Senate NDAA recommends a Chief Information Warfare Officer be appointed to oversee all policy relating to space and space-launch systems, the electromagnetic spectrum, and cyber warfare. The Chief Information Warfare Officer would also serve as the chief cyber adviser to the secretary of defense. This would amount to a sweeping reform of the way policy is formulated across these domains. Growing concern over America’s cyber capabilities also has an Asia-Pacific focus in the House NDAA. It directs the secretary to form a plan to enhance “joint, regional, and combined information operations and strategic communication strategies to counter Chinese and North Korea information warfare”, which would be largely focused on US Pacific Command in Hawaii.27 The prioritisation of these issues in FY 2018 reflects Congress’ growing concern that Russian and Chinese investments in new warfare technologies have catapulted them to near parity with America – an issue that has been repeatedly expressed by senior Pentagon officials.28

An oversized focus on ballistic missile defence

Ballistic missile defence (BMD) remains one of the biggest outlays in the US defence budget. But there is some disagreement between the Pentagon and Congress regarding its status as a funding priority. The Pentagon’s FY 2018 request for the Missile Defense Agency maintains current funding levels, putting it at odds with the Senate and House NDAAs which allocate more resources for BMD in the context of North Korea’s missile program.29 Some members of Congress have even floated the idea that increased funding for missile defence could be exempted from any continuing resolution in 201730 In terms of research, BMD continues to be one of the largest R&D accounts across the entire Defense Department at US$3.1 billion for defence-wide expenditure, an increase of $233 million over FY 2017.31 This trend is likely to continue. President Trump’s budget forecasts a 12-25 per cent increase in R&D funding for BMD between FY 2018 and FY 2022.

Ballistic missile defence remains one of the biggest outlays in the US defence budget. But there is some disagreement between the Pentagon and Congress regarding its status as a funding priority.

The House and Senate NDAAs devote significant sections to BMD. The House bill elevates missile defence to a Major Force Program alongside programs like Strategic Forces, Research and Development, and Special Operations Forces.32 If implemented, this move would unify all the elements of BMD into a single budget item, allowing for a more strategic approach to long-term planning and funding.33 The House NDAA also urges the Missile Defense Agency to begin developing a space-based BMD sensor and interceptor, budgets for a new boost phase BMD capability by 2020, and plans for a new BMD radar facility in Hawaii – which is also proposed in the President’s Budget.34 Similarly, the Senate NDAA calls for “persistent space-based sensor architecture” for BMD, urges the secretary of defense to accelerate the development of BMD capabilities, and increase the tempo of missile defence testing. To expand the accuracy and coverage of America’s Ground-Based Midcourse Defense system, the Pentagon has also requested a funding increase for the Sea-Based X-Band Radar to 330 days a year from its current 120 days.35

Implications for Australia

While the final defence budget is probably months away, there are signs that it will focus resources on strategic and operational challenges in Indo-Pacific Asia. Amid the ongoing budget uncertainty, this is welcome news for Australia and other regional allies. The Asia bills proposed by McCain and Thornberry – while smaller than their European counterparts – highlight a push by key stakeholders in Congress to focus US commitment on defending Asia’s rules-based order. Attention to military infrastructure and readiness in the region would, if implemented, offset some of the broader negative trend-lines in US power abroad. Although there is little doubt that the administration will sustain a “military-first rebalance” to Asia in the short-term, it is unlikely that Congress will succeed in broadening this into a integrated economic, political, and developmental strategy.36

A more sobering judgement for Australia from current budget deliberations is the reminder that the Budget Control Act – while only halfway through its scheduled lifespan – continues to prevent sensible and strategic defence budget planning. The BCA not only complicates the politics of defence spending and slows the budget process, but it also distracts Congress from a clear-eyed focus on major strategic issues like nuclear modernisation and competition with near-peer adversaries. It is encouraging that a growing number of US lawmakers are aware of the military’s readiness problems and resolved to address them. It is also positive that reforms are advancing in certain domains – like cyber and electronic warfare – which will deliver intelligence and technological benefits to allies like Australia. But simultaneous investment in military readiness, procurement, and modernisation cannot effectively take place until a political agreement is reached or the BCA expires. There is a risk that America’s global military lead may atrophy in the meantime.

Reports published by the United States Studies Centre are anonymously peer-reviewed by both internal and external experts.