Key takeaways

- The US federal government has been slow to confront the COVID-19 pandemic, but the US military will assume a much larger role as the virus and its impact spread to other states.

- The National Guard will likely contribute tens of thousands of troops to the response, but specialty units from active duty and reserve military units will also play a role.

- The US military’s response will primarily support civilian authorities to confront the public health crisis and quickly re-establish a fully functioning economy as rapidly as possible.

- The large-scale, combined use of National Guard units, active duty troops, and civil authorities will create coordination challenges and complicate response effectiveness.

- The United States is unlikely to recall troops from overseas deployments to augment the domestic response, but the COVID-19 response will hinder military training and readiness.

Introduction

Although the US federal government was slow to mobilise resources to confront the novel coronavirus (COVID-19), President Donald Trump and the Department of Defense on March 17 began taking several significant steps – including mobilising two hospital ships and medical supplies such as protective masks – to increase the military’s role in the pandemic response.1 On March 22, for example, President Trump announced he would activate National Guard troops in California, New York, and Washington state.2 Even this step, however, is likely to be insufficient to confront the challenges ahead as the crisis spreads to other states.

While domestic civilian agencies are ultimately the best-suited to lead the pandemic response, the capacity of the American public health system is likely to become rapidly stretched. There is much the military can – and should – do in a time of national crisis. As the crisis intensifies, the military will assume a larger role, but the effectiveness of the pandemic response, US national security, and American democracy will be better served if the military clearly maintains a supporting role.

Calling up the guard

US military forces can be used during domestic emergencies, and there are numerous examples of their use throughout American history. In fact, when George Washington sent troops to subdue an uprising of farmers and distillers protesting a whiskey tax during the Whiskey Rebellion in 1794, he demonstrated that the new federal government had the capacity to quell violent resistance to federal laws.3 The Army continued to play a major role in doing so for much of the 19th century, enforcing federal law on frontiersmen who encroached on federal lands and implementing the policies of post-Civil War Reconstruction in the late 19th century.4

Modern uses of the military for domestic purposes have instead tended to focus on disaster responses, such as assistance during Hurricanes Katrina in 2005 and Sandy in 2012 or support to the US Forest Service to fight forest fires in California. Most commonly today, the troops used in domestic emergencies are members of the National Guard. There are three primary ways members of the National Guard can be called into active service and each has different implications for who pays the bill and who controls the troops.5

US National Guard

The United States National Guard is a reserve military force that augments an active duty force of approximately 1.3 million personnel. The National Guard is composed of reservists and airmen assigned in each state and all four US territories, for a total of 54 separate organisations. The vast majority of the approximately 440,000 National Guard troops across the country hold a full-time civilian job while also serving part-time as members of the National Guard. Approximately 337,000 National Guard troops serve in the Army National Guard while 107,000 serve in the Air National Guard.

National Guard training consists of one weekend per month and two weeks per year, except when troops are activated for a mission. National Guard units can fall under either the control of the state or federal government, depending on what legal authority political leaders choose to invoke. The National Guard has been used for both domestic support to civil authorities as well as for combat in America’s wars.

State Active Duty

The simplest — and usually the fastest — way to activate the National Guard is called “state active duty (SAD)”. Under this approach, a state governor mobilises members of the Guard from their state in support of a state-level mission within state borders. The governor retains full control over all units, and the state funds all costs related to operations and activation. By March 27, across all 50 states and four territories, a total of 12,000 National Guard troops were able to be mobilised. But as the state wields the financial burden and as demand looked set to increase exponentially, governors pushed for alternative activation options.6

Title 10

At the opposite end of the spectrum, the president can activate the National Guard using his statutory authorities under “Title 10” of the US Code, the official codification of the general and permanent US federal statutes. These authorities effectively “federalise” the National Guard, bringing activated units under the control of the president as commander-in-chief, granting him the ability to use the troops anywhere he sees fit, and shifting the financial burden entirely onto the federal government. So far, the president has not fully federalised any National Guard units in response to the current pandemic, but previous presidents have very rarely used Title 10 authorities to activate portions of the National Guard in response to disaster relief operations such as hurricanes or wildfires. Title 10 is also the authority under which tens of thousands of National Guard personnel are activated for their two-week annual training as well as for deployments to the Middle East and Afghanistan.

Title 32

In activating the National Guards in hot spots like California, New York, and Washington, however, President Trump instead chose to use his “Title 32” authorities. Title 32 activation is essentially a hybrid between state active duty and Title 10 activation, under which the federal government assumes most of the financial burden while allowing governors to retain control over the National Guard units in their respective states.7 Title 32 activation is exactly what all state governors requested in a March 19 joint letter to President Trump because it provides them with maximum flexibility to address local challenges while relieving the financial burdens that SAD places both on the states and their troops. As of 2 April 2020, 10 states, two territories and Washington DC have had Title 32 activation approved, with an additional 27 requests underway.8 Expect to see requests and Title 32 activation to increase.

Table 1. Summary of National Guard Duty states

|

|

State Active Duty (SAD) |

Full-time National Guard Duty (Title 32) |

Federal Duty (Title 10) |

|

Command and control |

State governor |

State governor |

President |

|

Who pays |

State government |

Federal government |

Federal government |

|

Where |

State borders |

State borders |

Worldwide |

|

Notable examples |

Snowstorms (routine) California wildfires (routine) Flooding (routine) COVID-19 (2020) |

Airport security (2001-) Hurricane Katrina (2006) southwest border (2018-) COVID-19 (2020) |

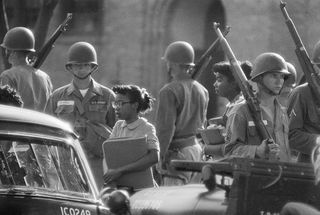

Little Rock School desegregation (1957) US Postal strike (1970) Hurricane Hugo (1989) Afghanistan (2001-) |

Command and coordination

Title 32 activations are not a panacea for resolving National Guard coordination challenges and could face several potential problems with respect to the COVID-19. Firstly, Title 32 activations are not designed to effectively coordinate the federal government’s response to a problem that crosses state boundaries because they rely on National Guard units conducting state-managed missions within state boundaries. As a result, neighboring state governors could implement competing policies and prevent the distribution of excess personnel and equipment to the most urgent needs or locations because governors are not required to help other states.

Secondly, Title 32 activations have historically relied on voluntary coordination between the states and federal civilian and military assets, with no clear unity of command 9 to ensure all organisations are working together toward a shared purpose.10 During Hurricane Katrina in 2005, for example, the Department of Defense designated Lieutenant General Russel Honore as the commander of federal relief operations in Louisiana and Mississippi. However, this arrangement caused problems because the governor of Louisiana refused to grant Honore command over Title 32 troops operating in his state.11 As a result, National Guard and Active Duty troops answered to different leaders who had different priorities, making coordination and resource allocation more difficult. When National Guard units aren’t fully-federalised under Title 10, coordination relies solely on voluntary cooperation between state and federal organisations.

The Department of Defense has attempted to mitigate challenges related to the use of the National Guard for disaster relief in the past. First, in 1999, Joint Task Force Civil Support was created to provide command and control of federal troops responding to domestic emergencies and to coordinate and assist in missions normally carried out by civilian authorities.12 In 2002, President George W. Bush placed Joint Task Force Civil Support under the new US Northern Command (USNORTHCOM), the combatant command in Colorado that is responsible for homeland defence.13 Although this task force still cannot control National Guard troops activated under Title 32, it has helped routinise coordination because it provides a standing, centralised command.

More recently, the military has attempted to tackle the problem of coordination between Title 10 and Title 32 units. In 2010, USNORTHCOM and the National Guard Bureau, the federal administrator of all national guards, partnered to create a position called a dual-status commander, a general officer in every state trained to simultaneously command the state’s National Guard forces under the state governor and the federal troops reporting to the active duty chain of command during disaster relief operations.14 This new arrangement ensured that both the National Guard and active duty troops answered to a dual-status commander during Hurricane Sandy relief operations in 2012 and Hurricane Harvey operations in 2017, greatly improving coordination between Title 32 and Title 10 troops.15 Together, these improvements have significantly mitigated challenges to cross-border operations and unity of command between state and federal authorities while ensuring the military remains in a supporting role during disaster relief operations.

Nevertheless, some analysts have predicted the COVID-19 will simultaneously place severe strain on the public health infrastructure of multiple states.16 If so, the National Guard could potentially play a larger role in domestic support to civilian operations than it has at any point in the modern era, testing its ability to coordinate across states and federal agencies at scale. Previous reforms have improved coordination for disaster relief operations within a single state, but these organisations have not been tested during a large-scale crisis simultaneously involving operations across multiple states.

A more active (duty) response

More than 17,000 National Guard Air and Army professionals have already been activated to support the COVID-19 response under either SAD or Title 32 orders, and that number seems likely to grow into the tens of thousands. While the National Guard can provide a large pool of manpower that understands local considerations quickly, units and capabilities are not equally distributed across states. Some states have more than 20,000 personnel with large amounts of equipment and logistics capacity while others have roughly 2,500 troops with limited capacity or inappropriate equipment. States’ resources could quickly be consumed since the local impact of the pandemic will vary across states. Moreover, in some cases, National Guard personnel already serve as civilian first responders, police, or medical personnel in their local communities. One estimate for Hurricane Katrina placed the number of National Guard soldiers unavailable for this reason to be more than 20 per cent.17 Others may have reported for National Guard duty, leaving shortages in their local communities. Activating guard members indiscriminately can pull them away from where they may be needed most. As a result, it is likely that some additional active duty soldiers and personnel may be called upon to fulfill specialised roles or surge personnel in support of authorities in the worst-hit areas.18

More than 12,000 National Guard soldiers have already been activated to support the COVID-19 response under either SAD or Title 32 orders, and that number seems likely to grow into the tens of thousands.

The Pentagon has the ability to utilise active duty soldiers or reserve units or personnel to provide additional capacity or capabilities that could become necessary as the civilian public health infrastructure or civilian governmental agencies are stretched beyond their capacity.19 Although almost 200,000 active duty US military personnel are deployed around the globe, roughly one million active duty service members remain in the United States and approximately 500,000 personnel remain in reserve status.20 While a large majority of these personnel are not organised or equipped to support operations immediately, military manpower dwarfs manpower in civilian organisations such as the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), with its mere 11,000 total personnel. This does not mean the military can replace public health officials or civilian agencies at the same level of effectiveness -- far from it in most cases. But it does mean that members of the active duty military can provide large numbers of personnel, supplies, and logistical capability quickly to allow more time to mobilise civilian resources. Additionally, the military can take on ancillary tasks to relieve pressure on civilian officials so that they are able to focus on healthcare provision.

Although there are some different statutory restrictions placed on active duty forces and members of the National Guard, there are few practical legal barriers placed on how they can be used during a domestic crisis. Now that President Trump has taken the unprecedented step of issuing a nationwide Stafford Act emergency – which unlocked additional resources for federal assistance to states upon their request – and issued the 61st US National Emergency declaration, he has a relatively free hand to use National Guard personnel and active duty troops to support civilian authorities for most activities.21 President Trump also can now reallocate some existing Department of Defense funds for other purposes.22

President Trump’s most controversial use of active duty troops and reallocation of Department of Defense funds in a domestic context has been in support of Department of Homeland Security operations at the southern border.23 Although this mission is extremely controversial, the courts have upheld the President’s authority to use federal troops and money for this purpose.

Some legal differences between the National Guard and active duty troops exist when it comes to use of the military for law enforcement purposes, but considerations tend to be more political than legal during a domestic crisis. Although commonly misunderstood, the Posse Comitatus Act, which applies only to active duty troops and not the National Guard, does not prevent the use of federal military forces for law enforcement. Rather, it forbids anyone from using the military to enforce laws, unless otherwise authorised by Congress or the Constitution.

Presidents have found ways to get around Posse Comitatus during previous crises. President Eisenhower invoked a post-Civil War Enforcement Act in 1957 to send the 101st Airborne Division to escort black children to school in Arkansas while George H.W. Bush invoked the Insurrection Act in 1992 to send the 1st Marine Division and the 7th Infantry Division to help quell the Los Angeles riots.24 President Trump so far has chosen not to use federal troops for law enforcement, but on March 28 he floated the idea of implementing a quarantine of Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York before deciding against it after he faced resistance from the New York governor.25 It remains possible that Trump could use the military in a law enforcement role in a dire situation. If he did so, it could be difficult for critics to roll back such action. In a different context, President Trump’s invocation of executive authority 26 to kill Iranian general Qasim Soleimani demonstrates that the President’s first-mover advantage can make it difficult for Congress to curtail this type of presidential action, especially in a crisis when a president can likely count on support from co-partisans in Congress.

More Marshall Plan than Martial Law

Despite the recent proliferation of conspiracy theories asserting otherwise, it is extremely unlikely President Trump will use the military to impose large-scale martial law.27 It is possible, however, that the National Guard – and even active duty troops – could play a role in enforcing quarantines, limiting movement, or securing critical infrastructure and supply nodes. Active duty troops on alert usually provide the fastest way to reinforce civil authorities if a state’s law enforcement capacity becomes overwhelmed. Still, using soldiers this way carries risk. Service members are heavily armed and most are not trained as police.28 The few military police the military does possess usually have little experience in civilian law enforcement. And, as violence resulting from National Guard involvement in union-busting in the late 19th century and bayonet injuries during Little Rock school desegregation in the 1950s show, it is usually best to keep the military focused on other missions.

As the crisis unfolds, the military will focus its efforts on supporting civilian authorities attempting to confront the public health crisis so that the United States can quickly re-establish a fully functioning economy. Secretary of Defense Mark Esper has stated, however, that the Department of Defense wants “to be the last resort” in reliefs efforts related to COVID-19.29 In fact, the 2018 National Defense Strategy – unlike the most recent defence guidance issued as part of the 2014 Quadrennial Defense Review – contained no mention of the military’s role in pandemic response, instead prioritising great power competition with China and Russia.[30]

This reluctance is understandable. The military is not a substitute for public health infrastructure and cannot be expected to lead the charge against the COVID-19. Moreover, pulling active duty assets and personnel away from their primary missions creates real costs in terms of military readiness and national security. Nevertheless, the military can provide two things that are needed in a pandemic response: speed and capacity. These two factors are a major reason why the military – including some National Guard soldiers – played a major role in the US government’s response to the Ebola outbreak in Liberia in 2014 despite wanting to be the last resort for that mission as well.31

The 2018 National Defense Strategy – unlike the most recent defence guidance issued as part of the 2014 Quadrennial Defense Review – contained no mention of the military’s role in pandemic response, instead prioritising great power competition with China and Russia.

Even in the Liberia case, however, the military focused on enabling civilian officials to confront the Ebola health crisis indirectly, by focusing on the types of tasks the military does better than civilian agencies, especially at large-scale: organisation and logistics. In Liberia, the Pentagon deployed almost 4,000 troops who provided supplies, logistical support, training, construction, and vaccine research. Military support to civilian authorities confronting the COVID-19 will likely focus on these same types of tasks.

The Department of Defense will certainly provide some high-profile medical assets, such as sending the USNS Comfort and Mercy hospital ships to New York and Los Angeles, respectively, as well as deploying field hospitals and providing mobile labs to process tests.32 These contributions will not provide direct medical support to patients suffering from the COVID-19, but instead will provide trauma treatment and routine medical care to free up capacity so that civilian professionals can focus on COVID-19 treatment directly.33 Nevertheless, the most substantial military contributions are likely to come in the following areas, with members of the National Guard providing the vast majority of the manpower:

Supplies

The Department of Defense has already committed to make a significant contribution of protective equipment to individual states, including nearly five million N95 masks and 2,000 ventilators.34 Additionally, the military has delivered more than 500,000 COVID-19 tests from military stocks, with more likely on the way.35 President Trump also has broad authority under the Defense Production Act (DPA), a Korean War-era law that enables him to compel industry to accept government contracts for critical supplies and to prioritise them ahead of private orders. The law also provides expansive powers and financial tools that allow the president to rapidly expand domestic production capabilities needed for national defense. Although President Trump was initially reluctant to exercise his full powers under the DPA, he has now granted the Secretary of Health and Human Services the authority to use the DPA to order General Motors to produce ventilators and is likely to further apply the DPA as equipment shortfalls become more apparent.36 In the state of New York alone, for example, Governor Andrew Cuomo has claimed that his state will need at least 30,000 additional ventilators after receiving only 400 from FEMA, although President Trump has questioned these numbers.37

Personnel

The National Guard and, if necessary, active duty units can provide large numbers of young, healthy personnel on relatively short notice. Some small units will provide niche capabilities to help expand civilian screening capacity, such as train-the-trainer teams. But the large numbers of able-bodied individuals can play a larger role in providing additional capacity to clean and disinfect common areas or medical facilities, screen and in-process patients at understaffed hospitals, stock shelves if supply chains break down, or support medical personnel and local police if requested.38

Logistics

The military can provide large numbers of trucks, helicopters, and other aircraft that can help deliver supplies within cities and states, and even across the country if FEMA requires support to re-allocate federal stockpiles and re-distribute state supplies to other states or cities that need them more urgently.39

Construction

In addition to providing military field hospitals and hospital ships, the US Army Corps of Engineers is also supporting FEMA to rapidly expand hospital capacity by adding 10,000 beds in New York City alone.40 In response to prioritised state requests, the Army Corps of Engineers executes contracts to quickly renovate existing buildings, such as dorms and unoccupied hotels, to increase the number of locations available for use as emergency intensive care units (ICUs).

Vaccine development

US government military laboratories are working to develop a vaccine for the fast-spreading COVID-19, as they have for previous outbreaks, including during the Ebola crisis.41 US military researchers have an excellent track record and have played a major role in developing vaccines for diseases such as yellow fever, adenovirus, and many others throughout history.42

Looking forward

As the effects of the pandemic expand throughout the United States, we should expect members of the National Guard and the active duty military to increase into the tens of thousands. It is possible these activations could rival or exceed levels seen during the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, previously the largest domestic response mission conducted by the US military when more than 45,000 guardsmen operated in Louisiana and Mississippi.43 A relief effort at this scale, carried out over weeks or months, would create a significant drain on core Department of Defense priorities.

As the effects of the pandemic expand throughout the United States, we should expect members of the National Guard and the active duty military to increase into the tens of thousands. It is possible these activations could rival or exceed levels seen during the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.

There is no modern precedent of a US president withdrawing military forces from overseas missions in support of a domestic emergency. It is possible, however, that the COVID-19 response will provide domestic political actors with additional ammunition to intensify their calls for faster troop reductions in Iraq and Afghanistan. These political arguments are less likely to gain traction in discussions about US force posture in the Indo-Pacific region. Secretary of Defense Esper has fully endorsed the 2018 National Defense Strategy’s focus on great power competition, and he remains unlikely to reallocate military forces away from this region.

Although the US military’s increasing role in the domestic response to the virus is unlikely to cause the US government to recall military units from overseas missions, it could disrupt the timing of deployments and transitions between units. COVID-19 will also impact military training and readiness. Much like their civilian counterparts, US military leaders are making decisions about which activities are essential and how to enforce social distancing during training and exercises. So far, their interventions have been minimal, but disruptions are increasing.44 On March 27, the Commander of US Forces Korea, General Robert Abrams, ordered his units to a bare-bones posture with only watch teams in place and all other personnel under a shelter-in-place order.45 As COVID-19 cases increase in the US military’s own ranks, there will be pressure to cancel more training to preserve readiness. Nevertheless, the United States has “redundancy in its tools of influence — and this may buy some peace of mind” in this moment of uncertainty.46

But the COVID-19 response will place a real burden on US military forces, and it will draw resources and funding from training the US military would prefer to be doing over the next weeks and months. Current projections suggest COVID-19 cases in the United States will peak in mid-April, though high case-levels and hospitalisations may persist until the summer in some areas.47 If these projections materialise, the US military is the only organisation with the speed and capacity to provide much-needed manpower.