Foreword

Gauging public opinion is a key tool for policy makers and others to better understand levels of popular concern about issues and support for national priorities. This also applies to foreign policy and international relations. In October 2015, the United States Studies Centre at the University of Sydney and the Perth USAsia Centre at The University of Western Australia, in cooperation with a network of partner institutions, conducted a public opinion survey on America’s Role in the Asia-Pacific almost simultaneously and with nearly identical questions in Australia, China, Indonesia, Japan and Korea. The results of this survey were released in 2016 with a particular focus on comparing and contrasting different national perspectives on the major issues in the region.

While a single data point or “snapshot” is interesting, additional data points, particularly over time, provide the opportunity to identify trends and assess the impact of particular developments on public opinion. Between Brexit in the United Kingdom, the election of Donald Trump in the United States, tensions in the South China Sea and progress in North Korea’s missile and nuclear programs, there were significant developments in 2016 which might be presumed to influence public opinion in Asia about America’s role in the region.

To test that presumption, in March of 2017 we conducted a second survey, composed largely of the same questions as our first survey with a few new questions to capture specific reactions to recent developments.

As in 2015, this process has benefited tremendously from the collaborative efforts of a network of partner institutions in the region. In addition to the United States Studies Centre and the Perth USAsia Centre in Australia, we were joined by the Foreign Policy Community Indonesia, the Shanghai Institutes for International Studies in China, the Canon Global Institute in Japan and the Asan Institute for Policy Studies in Korea. Of note, in recognising the growing reality of an “Indo-Pacific” region, this year we opted to expand the survey to include results from India and we welcomed Brookings India to our network. As before, this “Indo-Pacific Research Network” worked together to help refine the survey and analyse the results. This summary publication not only includes an overview of key findings, but also country-specific chapters from each of our partner institutions, highlighting the results most relevant to their national perspectives.

Once again, we recognise the excellent survey work done by other organisations such as the Pew Research Center, the Chicago Council on Global Affairs and others in the region, including our network partners. It is our hope that this survey, conducted as it has been by a network of institutions based in the Indo-Pacific and benefiting from a collective regional perspective in approach, will provide a point of view unique to those surveys driven by US-based institutions.

Professor Simon Jackman

Chief Executive Officer, United States Studies Centre at the University of Sydney

Professor Gordon Flake

Chief Executive Officer, Perth USAsia Centre at the University of Western Australia

Executive summary

The survey was conducted during the first weeks of March 2017. During this period, the global landscape was dominated by events that included the US presidential election campaign, the lead-up to an Australian Federal election, the slowdown of Chinese economic growth to a “new normal”, the acceleration of North Korea’s nuclear missile testing, the impeachment of South Korean President Park Geun-Hye and the deployment of the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) system on the Korean Peninsula. These events, in the region and beyond, provide the backdrop against which responses were gathered.

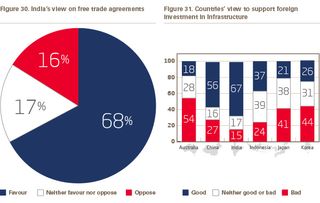

The overall survey results show that assessments of American influence and value in the region have diminished — particularly in Australia, Japan and Korea, but not in China. All surveyed countries, except China, generally perceive that the United States has a positive influence in the region, all countries see trade with the United States as overwhelmingly positive and all countries are in favour of free trade agreements. India (67 per cent), China (54 per cent) and Indonesia (37 per cent) welcome foreign investment in critical infrastructure while Korea (26 per cent), Japan (21 per cent) and especially Australia (18 per cent) do not. Highest levels of isolationism were reported in India (50 per cent) and Australia (43 per cent) with China reporting the lowest levels (18 per cent). Among all surveyed countries, Australia and Korea place the highest value on democracy although all value democratic forms of government.

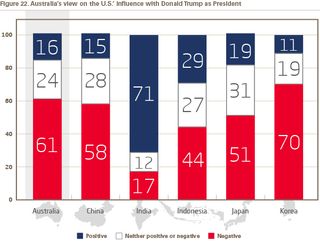

More than half of Australians perceive American influence in the next five years as negative under US President Donald Trump.

In Australia, respondents increasingly see China as having the most influence in the Indo-Pacific region (72 per cent). More than half of Australians (62 per cent) perceive American influence in the next five years as negative under US President Donald Trump. Despite this, most Australians (71 per cent) still see the United States as the global "rule setter" and the majority of Australian respondents (93 per cent) believe in the Australia-US alliance such that in the event of a crisis America would come to Australia’s aid. Australians remain concerned about Islamic extremism (37 per cent) although are increasingly concerned about possible involvement in a conflict with China (13 per cent) and internal political instability among its Asian neighbours (12 per cent).

In China, most perceive the influence of the United States in the region as declining with its best years in the past (71 per cent) and see the United States as doing more harm than good in the region (43 per cent). The majority of Chinese respondents appreciate the importance of the US-China bilateral relationship and feel it has improved since the 2016 report despite the public negativity towards China expressed during President Trump’s election campaign. More than half of Chinese respondents (65 per cent) believe China will eventually become a superpower and replace the United States. Chinese respondents generally perceive isolationism unfavourably (82 per cent), however, concern about a conflict between North and South Korea has markedly increased amongst Chinese respondents (64 per cent).

Indian respondents are the most optimistic about the United States with 61 per cent believing that its best years are ahead of it. Strikingly, 53 per cent of Indian respondents believe that India will have the most influence in Asia in the next ten years, contrasting with the views of Japan (15 per cent), Australia (6 per cent), South Korea (3 per cent), China (1 per cent) and Indonesia (1 per cent). More than half of Indian respondents (52 per cent) feel that the United States does more good than harm, should increase its military presence in Asia (53 per cent) and has a positive influence on India (65 per cent). In contrast, 48 per cent of Indian respondents feel that China generally does more harm than good in the region and has a negative influence on India (46 per cent). However, 47 per cent also feel that ties between India and China should be stronger. Indian respondents were generally conscious of an intensification in US-China competition characterising that relationship by fear (77 per cent), and many feel that a US-China conflict (40 per cent) was more likely than a conflict in the Korean Peninsula (37 per cent), although Indians still rated an Indian-Pakistan conflict as more likely (55 per cent). There was a 50-50 split with Indian respondents believing that India would be better off “staying home” and not concerning itself with problems in other parts of the world, in contrast with China (18 per cent) and Korea (23 per cent). Indian respondents also have concerns about immigration and its impact on employment (42 per cent) and culture (41 per cent) and feel strongly that being born in India (78 per cent), having respect for Indian institutions (77 per cent) and “feeling Indian” are of utmost importance (78 per cent).

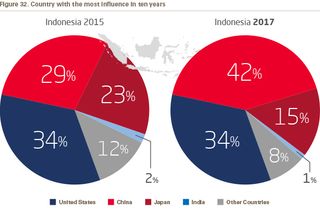

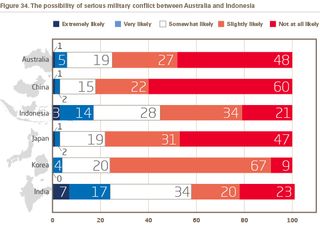

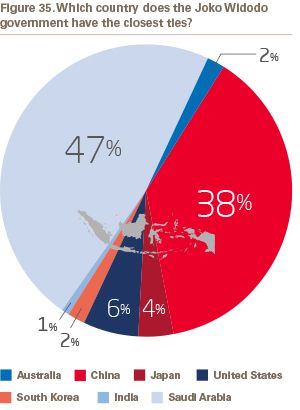

More Indonesians feel that President Trump will have a negative influence on the region (44 per cent) than a positive influence (29 per cent). China (58 per cent) has overtaken the United States (46 per cent) as the country with most current influence in Asia according to Indonesian respondents as well as having the most influence in ten years’ time, although respondents had a generally positive view on the influence the United States has on Indonesia (40 per cent). The threat from Islamic extremism (31 per cent) has replaced “China’s increasing economic power” (0 per cent) as America’s greatest challenge according to Indonesian respondents. The majority of Indonesian respondents (67 per cent) believe there will be a serious military conflict between the United States and China. An even greater majority (73 per cent) believe there will be a serious military conflict between the United States and Russia. Less than half of Indonesians surveyed (45 per cent) also see a conflict between Indonesia and Australia as “likely”, significantly higher than Australians’ perceptions (25 per cent) of an Australia-Indonesia conflict. Indonesian respondents feel closest to Saudi Arabia (47 per cent) and that Malaysia is the most hostile towards them (41 per cent). Indonesian respondents are highly concerned about the effects of immigration stealing Indonesian jobs (97 per cent), although the notable majority (74 per cent) do not feel Indonesia should isolate itself from problems in other parts of the world.

South Koreans think the Trump presidency will not be helpful in addressing the situation in North Korea and most identify the development of North Korea’s nuclear weapons and military provocations as the most serious threat to South Korea’s national security.

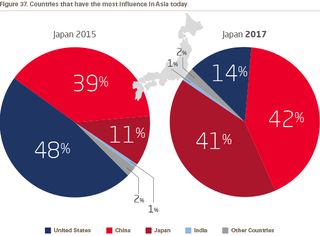

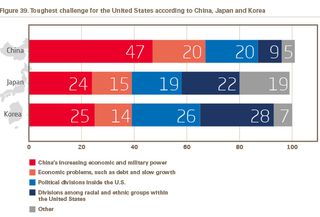

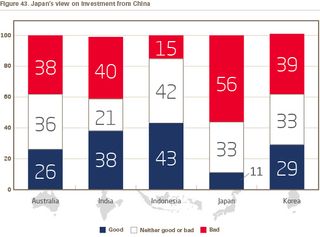

Japanese respondents perceive China and Japan to have the most influence in Asia today (42 and 41 per cent respectively) with a significant decrease in the perception of American influence (decreased by 34 per cent from previous survey). A greater proportion of Japanese respondents see US domestic issues, particularly its domestic economy (15 per cent), internal political division (19 per cent) and racial/ethnic divide (22 per cent), as more challenging to America than China’s increasing military (17 per cent) and economic power (7 per cent). A notable majority of Japanese respondents do not believe that China will overtake the United States as a superpower (78 per cent) and Chinese investment in Japan is generally viewed negatively (71 per cent).

South Koreans generally perceive China as having an increasingly negative influence on the region, as well as the decline of US influence, especially President Trump. There has generally been a rise in anti-China sentiment in South Korea with 60 per cent of South Koreans perceiving China as having a negative influence — a 38 per cent increase from the previous survey. However, half of South Korean respondents (50 per cent) felt the relationship should be strengthened and that trade with China has a positive effect (45 per cent). South Koreans generally view foreign investment in critical infrastructure unfavourably (75 per cent) and also hold unfavourable views about China’s military expansion in the region (47 per cent). A majority of South Korean respondents feel that the election of President Trump will negatively affect South Korea (70 per cent) and expect the relationship between South Korea and the United States to be “bad” (72 per cent). South Koreans also think the Trump presidency will not be helpful in addressing the situation in North Korea (72 per cent) and most identify the development of North Korea’s nuclear weapons and military provocations as the most serious threat to South Korea’s national security (68 per cent).

America’s role in the Indo-Pacific

Authors: Simon Jackman, Professor and CEO, United States Studies Centre at the University of Sydney and Luke Mansillo, PhD Candidate, United States Studies Centre

The tumultuous 2016 US presidential election campaign, its outcome, and the eventful start to the Trump administration set the stage for this iteration of the survey distributed in late February and early March 2017, just one month into the Trump presidency. As a candidate and in his inauguration speech, Trump promised to remake America’s relationship with the world, to put “America First.” As a candidate, Trump argued that its allies ought to shoulder more of the costs of their national defence and perhaps should arm themselves with nuclear weapons. A more robust approach to China in trade and security was also a key part of Trump’s agenda as a candidate. During the interregnum, Trump and Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen spoke by phone, sparking intense speculation as to Trump’s intentions with respect to China and possible reactions from Beijing.

Shortly after taking office, and before the survey had been distributed, Trump announced that the United States was withdrawing from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). President Trump also signed executive orders that directed the US Government to minimise costs and burdens stemming from the operation of the Affordable Care Act (aka “Obamacare”) and restricted entry to the United States from seven, majority Muslim nations (later blocked by the courts). On 13 February 2017, Trump’s National Security Advisor Michael Flynn, resigned after acknowledging he had misled officials (including the Vice President) about the nature of his communications with Russian diplomats, renewing controversy about possible ties between the Trump campaign and Russian attempts to influence the outcome of the 2016 US presidential election.

How have these developments in the United States shaped attitudes about America’s role and its influence in the Indo-Pacific and on specific countries? Have assessments of security challenges changed? Has Trump’s “America First” message — backed up by America’s withdrawal from the TPP — changed attitudes towards international trade and investment in the region? This survey was designed to answer those questions.

Summary of findings

- Assessments of American influence in the Indo-Pacific have diminished, and by large margins among American allies such as Australia, Japan and Korea. Of the six countries surveyed, Australian respondents are the most likely to nominate China as the most influential country in Asia today (72 per cent) and the least likely to nominate the United States (11 per cent).

- Assessments of American influence on specific countries remain positive in all countries, except China. Australians are indifferent with respect to the value of American versus Chinese influence on Australia (continuing a pattern observed in the previous survey), while Indian, Japanese and Korean respondents give much more positive evaluation to the influence of the United States on their respective countries.

- Trade with and investment from the United States is seen as overwhelmingly positive for all countries. Korea, Japan and India would prefer increased trade with the United States over China, while the opposite holds in Indonesia and Australia. In all countries, investment from the United States is strongly preferred over investment from China.

- Foreign investment in critical infrastructure is welcomed in the developing countries surveyed (Indonesia, India, China), but faces more opposition than support in Japan, Korea and especially in Australia.

- The Korean Peninsula remains the most likely site of a militarised conflict. North Korea is thought to be the country most likely to initiate a conflict in four out of six countries surveyed. Chinese suspicions about Japanese militancy remain high, but have fallen substantially from the previous survey.

- Conflict between the United States and China is generally seen as more likely now than in the previous survey, but is still seen as a relatively remote prospect in most countries. Just 10 per cent of Chinese respondents report a US-China conflict as being “very” or “extremely” likely.

- Nationalism runs high in Indonesia and India, followed by China. Australians report the lowest levels of nationalism among the six countries surveyed. Increasing levels of nationalism predicts a desire for stronger ties with the United States in all countries except China and Indonesia. Increasing levels of nationalism also predicts wanting stronger ties with the United States and less strong ties with China in Japan and India.

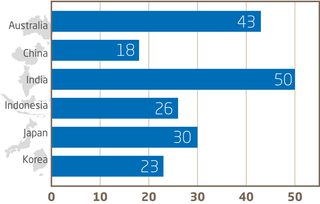

- Isolationism runs high in India and Australia. Fifty per cent of Indians and 43 per cent of Australians agreed that “this country would be better off if we just stayed home and did not concern ourselves with problems in other parts of the world.” Only 18 per cent of Chinese accept that proposition.

- Free trade agreements (FTAs) are favoured in all six countries. Korea is the most predisposed towards free trade, by a favourable-to-unfavourable margin of 56 per cent. Australia is the least in favour of free trade, with favourable attitudes outpacing negative attitudes towards FTAs by 29 per cent.

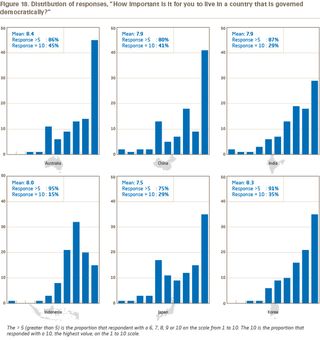

- Democratic forms of government are highly valued in all six countries surveyed, but with Australia and Korea scoring especially high on this measure. Japanese respondents recorded the lowest “importance of democracy” score. The importance of democracy varied by age in Japan and Australia, with older respondents especially emphatic about democracy. The opposite pattern holds in China, with cohorts socialised during the Cultural Revolution less likely to report that democracy is important to them.

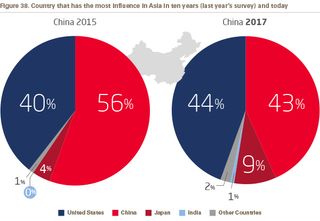

US allies report diminished US influence in the Indo-Pacific

Assessments of American influence in Asia have diminished in Australia, Indonesia, Japan and Korea, but not in China. The falls in Japan and Korea are especially large. In the previous survey, 48 per cent of Japanese respondents nominated the United States as the most influential country “in Asia today;” this percentage has fallen to just 14 per cent. In Korea, the fall is from 60 to 31 per cent and from 22 to 11 per cent in Australia. Assessments of China’s influence in Asia are higher in Indonesia and Korea and stable everywhere else, except in China itself (see Figure 1). Japanese respondents are much more likely to nominate Japan as the country with the most influence in Asia than in the previous iteration of the survey. Forty four per cent of Indian respondents nominated India as the country with the most influence in Asia today; just 2 per cent of Australians shared this assessment, and even smaller percentages elsewhere.

Of the six counties surveyed, Australian respondents are the most likely to nominate China as the most influential country in Asia today (72 per cent) and the least likely to nominate the United States (11 per cent).

There is more agreement about which country will be the most influential in Asia ten years from now (see Figure 2). China is the plurality choice in Australia (64 per cent), China (74 per cent), Indonesia (42 per cent), Japan (31 per cent) and Korea (66 per cent), with Indian respondents rating China behind India (53 per cent) and the United States (21 per cent).

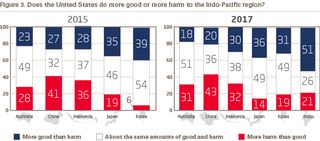

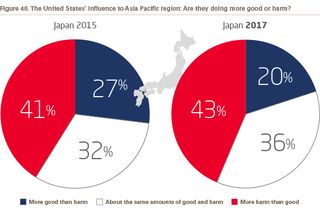

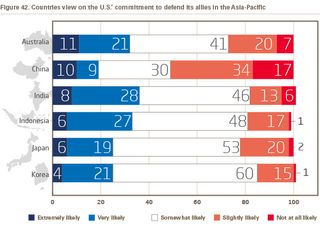

Evaluations of America’s impact on the Indo-Pacific are largely unchanged from the previous survey (see Figure 3). Japan and Korea remain especially positive in their evaluations of whether the United States “does more good or harm” to the Indo-Pacific region, with 36 per cent of Japanese respondents (previously 35 per cent) and 31 per cent of Korean respondents (previously 39 per cent) reporting “more good than harm.” Fifty two per cent of Indian respondents see the United States as doing more good than harm in the Indo-Pacific region, far and away the most positive assessments of the United States among the six countries surveyed. Just 20 per cent of Chinese respondents see the United States as doing more good than harm (down from 27 per cent), while 18 per cent of Australians report that the United States does more good than harm in the Indo-Pacific, down from 23 per cent in the previous survey.

At the same time, Australians do not have especially favourable views of the impact of China on the Indo-Pacific. Just 21 per cent of Australians rated China as doing more good than harm (down from 24 per cent). Koreans and Japanese respondents have even more negative assessments of China’s impact, with just 13 and 9 per cent respectively offering positive assessments of China’s impact on the Indo-Pacific while 63 per cent of Chinese respondents rated China’s impact as positive (down from 70 per cent in the previous survey).

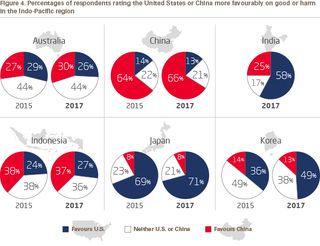

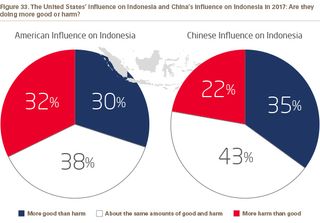

Australians are the most likely to offer even-handed assessments of the impact of both China and the United States (see Figure 4) with 51 per cent of Australians saying the United States does about the same amount of good and harm to the Indo-Pacific, 50 per cent make the same assessment of China’s impact and 44 per cent give the same assessment of the United States as they give China. Thirty per cent of Australians give more positive assessments to China than to the United States, while 26 per cent give more positive assessments to the United States. The resulting net positive score of 4 per cent towards China is statistically distinguishable from zero, but the smallest US/China differential across the six countries surveyed. Indian respondents have much more positive evaluations of the United States over China (+33 per cent), as do the Japanese (+63 per cent) and Koreans (+36 per cent). Indonesians rate Chinese influence on the Indo-Pacific more positively than American influence (+10 per cent towards China). Unsurprisingly, Chinese respondents are the most positive about China’s influence on the Indo-Pacific, with a net positive score for Chinese influence over US influence of 53 per cent.

Does the United States have a positive influence on specific countries?

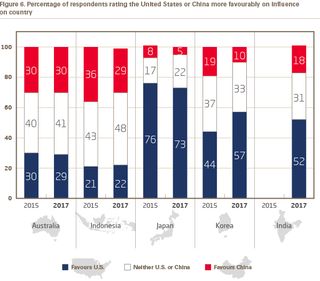

Respondents were asked if the United States had a positive or negative influence on their country, (see Figure 5). Positive assessments outnumbered negative assessments in Australia (+8), India (+44), Indonesia (+15), Japan (+30) and Korea (+19); only in China are negative assessments of US influence more prevalent than positive assessments (-45). Evaluations of American influence have become less sanguine in Australia since the previous survey (+16 to +8), as well as in China (-3 to -45) and Korea (+40 to +19), with Japanese assessments unchanged (+32 to +30).

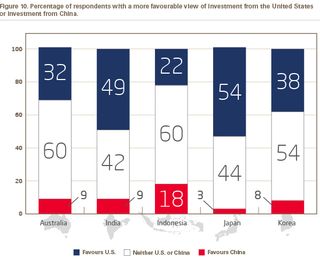

Figure 6 displays the proportions of respondents giving either the United States or China more favourable assessments with respect to the influence of those countries on their home country. This comparison is not meaningful for Chinese respondents. Australian responses are indistinguishable from their responses in the previous survey, with four in ten Australians giving the same rating to both China and the United States. Roughly equal proportions of Australians rated the United States over China and vice-versa.

Indonesian respondents displayed a slight tendency to evaluate China’s influence more favourably than that of the United States, 29 to 22 per cent for a net positive towards China of 7 per cent, down from a 14 per cent net positive rating in the previous survey. Other countries surveyed all reported much more favourable evaluations of the influence of the United States relative to their evaluations of China. In Japan, the net positive score in favour of the United States was 68 per cent (67 per cent in the previous survey). In Korea, this figure was 47 per cent (previously 25 per cent) and in India was 34 per cent.

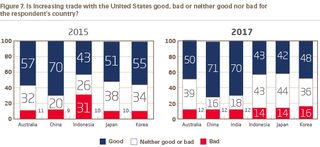

Trade with the United States

Increasing trade with the United States is generally perceived as a good thing in every country surveyed (Figure 7), with very little change from the previous survey. Fifty per cent of Australians (previously 57 per cent) have a positive view of increased trade with the United States while 71 per cent of Chinese respondents (previously 70 per cent) hold this view, as do 43 per cent of Indonesians (no change), 42 per cent of Japanese (previously 51 per cent) and 48 per cent of Koreans (previously 55 per cent). Seventy per cent of Indians report a positive view of increasing trade with the United States (see Figure 7).

Figure 8 contrasts preferences for increased trade with the United States with China. Twenty seven per cent of Australians are more positive about increasing trade with the United States than with China, while 17 per cent hold the contrary views, for a net positive towards increased trade with China of 10 per cent (unchanged from the previous survey). Indonesians also have a slight tendency to report more positive views about trade with China than with the United States, a net positive towards China of five per cent. In Japan, Korea and India, there is a clear preference for increasing trade with the United States over China, with net positive ratings of 27 per cent in Japan (down from 35 per cent in the previous survey), 7 per cent in Korea (a swing from a 7 per cent net positive towards China over the United States in the previous survey) and a large 37 per cent net positive towards the United States in India (see Figure 7).

Investment from the United States

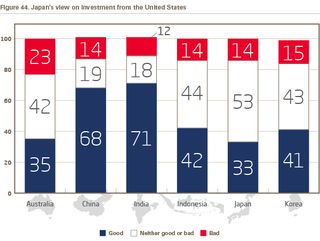

Respondents were asked a similar set of questions about investment from the United States; these questions that were not asked in the previous survey. Figure 9 displays these results with 23 per cent of Australians reporting that investment from the United States is either bad or very bad for Australia, the highest proportion of negative assessments among the six countries surveyed; the corresponding percentages are 13 per cent in China, 12 per cent in India, 14 per cent in Indonesia and Japan and 15 per cent in Korea. Positive assessments of US investment tended to outweigh negative assessments, with 68 per cent of Chinese respondents reporting that investment from the United States is either good or very good for China; the corresponding percentages are 71 per cent in India, 42 per cent in Indonesia, 41 per cent in Korea, 35 per cent in Australia and 33 per cent in Japan.

Not only is investment from the United States generally seen as desirable, it is also generally seen as more desirable than investment from China. Thirty two per cent of Australians expressed more positive sentiment towards investment from the United States than from China, with just 9 per cent holding the contrary view for a net positive of 23 per cent towards the United States. Net positive scores for US-sourced investment over investment from China ranged from 51 per cent in Japan and 40 per cent in India, to just 4 per cent in Indonesia.

Security challenges

Respondents were asked questions about the likelihood of various interstate conflicts that could arise in the region, as well as to nominate which country might be most likely to initiate conflict.

Concern over North Korea

Figure 11 summarises responses about which country is likely to start a conflict in the Asia-Pacific. In four out of six countries, North Korea remains the most likely belligerent, at rates that vary from 59 per cent in Japan, to 31 per cent in Indonesia. The exceptions are China, where Japan remains the country thought to be the most likely to start a conflict (24 per cent, but sharply down from 56 per cent in the previous survey), and India, where 35 per cent reported that China is most likely to start a conflict.

After North Korea, China is perceived to be the next country most likely to start an interstate conflict. Thirty five per cent of Indians rated China most likely to start a conflict, 29 per cent of South Koreans also nominated China (up from 8 per cent in the previous survey), as did 25 per cent of Japanese respondents (down from 37 per cent in the previous survey). Fifteen per cent of Indonesians and 13 per cent of Australians nominated China as most likely to start a conflict in the Indo-Pacific.

Dumping on Trump is no boost for Beijing

Heightened fears about conflict on the Korean Peninsula have helped reduce the rate at which respondents see Japan as initiating conflict. In the previous survey 56 per cent of Chinese respondents nominated Japan as most likely to start the next regional conflict; this has more than halved to 24 per cent. Similarly, only 16 per cent of South Koreans nominated Japan as most likely to initiate conflict, down from 22 per cent in the previous survey.

There is very little movement in the rate at which respondents nominate the United States as the country most likely to initiate conflict in the Indo-Pacific with rates ranging from 4 per cent in Japan to 22 per cent in Indonesia. Australia is the only country with a significant increase in the rate at which the United States was selected: 19 per cent versus 10 per cent in the previous survey. More Australians think the United States is the country most likely to initiate an Asian-Pacific conflict than China (19 to 13 per cent), a reversal of the results in the previous survey. Indeed, Australians nominated the United States as the initiator of conflict at higher rates than the Chinese (13 per cent), Indians (13 per cent), Japanese (4 per cent) or Koreans (5 per cent).

Specific interstate conflicts

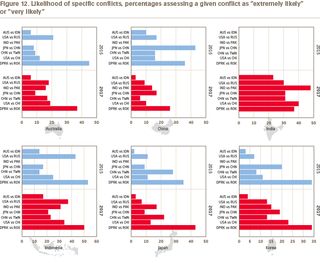

Respondents were asked about the likelihood of seven specific conflicts: (1) between North and South Korea; (2) Japan and China; (3) the United States and Russia; (4) China and Taiwan; (5) the United States and China; (6) Australia and Indonesia; and (7) India and Pakistan. Figure 12 summarises the responses, presenting the percentage of respondents assessing each conflict to be “very likely” or “extremely likely,” by year and country of respondent. Note that respondents were not asked about a possible India-Pakistan conflict in the previous survey.

Again, a North and South Korea conflict is thought to be the most likely of the seven hypothetical conflicts presented to respondents in five out of six countries. Half of Indonesian respondents rated a North Korea-South Korea conflict as “very” or “extremely” likely; a quarter of Chinese respondents made that assessment. Yet, with the exception of Japanese respondents, the likelihood of a Korean conflict is generally seen as unchanged or slightly lower than in the previous survey. Assessment was unchanged in South Korea, with 34 per cent reporting that conflict with the North is very or extremely likely.

In China, there was a sharp decline in the proportion of people who believe that a conflict would emerge between China and Japan. In 2017, 17 per cent of Chinese respondents thought a conflict with Japan was very or extremely likely. This is a 26 per cent decline from our previous survey, in which 43 per cent of Chinese respondents assessed a conflict with Japan as very or extremely likely. There were no other significant shifts in views in the other countries studied.

A more belligerent United States?

In most of the countries surveyed the results show a greater likelihood attached to a US-China conflict than in the previous survey. In Australia, the percentage of respondents assessing this conflict as very or extremely likely increased from 12 to 19 per cent; in Indonesia, the increase is from 25 to 34 per cent; in Korea the increase is from 11 to 23 per cent; in Japan the increase is small and not statistically significant, from 11 to 13 per cent. Indian respondents attached the highest likelihood to a US-China conflict with 40 per cent rating it as very or extremely likely. Chinese respondents attached the lowest likelihood to a US-China conflict, with just 10 per cent assessing it as very or extremely likely, down from 16 per cent in the previous survey.

A US-Russia conflict is generally seen as less likely than in the previous survey, according to respondents in Australia, China, Indonesia and Japan while 13 per cent of Koreans say that a US-Russia conflict is very or extremely likely, up from 7 per cent in the previous survey. Indonesians believe a US-Russia conflict is more likely than a US-China conflict (37 per cent versus 34 per cent) or an India-Pakistan conflict (31 per cent) and second only to a Korean conflict (50 per cent reporting very or extremely likely).

Assessing a China-Taiwan conflict

A serious military conflict between China and Taiwan is considered more likely in Australia, Indonesia and Korea in 2017 compared to the previous survey, but the reverse is true in China and Japan. Seventeen per cent of Australian respondents (up from 9 per cent), 23 per cent of Indonesians (up from 14 per cent) and 13 per cent of Koreans (up from 8 per cent) all report that a conflict between China and Taiwan is very or extremely likely. Conversely, there was a 10 per cent decline in China with just 6 per cent of respondents assessing a China-Taiwan conflict as very or extremely likely. Thirty one per cent of Indian respondents think a China-Taiwan conflict is very or extremely likely, the highest rate among the six countries surveyed. Chinese assessments of the likelihood of this conflict differed markedly from those in all other countries: while just 6 per cent of Chinese rated this conflict as very or extremely likely, the corresponding rates elsewhere are two to five times higher.

The low likelihood of an Australia-Indonesia conflict

An Australia-Indonesia conflict is considered the least likely of the seven conflicts respondents were asked about. There has been little change on views towards the likelihood of a conflict between Australia and Indonesia since the previous survey. Just 3 per cent of Chinese respondents considered this conflict as very or extremely likely, down from 10 per cent while 3 per cent of Japanese respondents and 4 per cent of Korean respondents assessed an Australian-Indonesian conflict as very or extremely likely.

Australian and Indonesian respondents’ assessments of a conflict between the two countries are also low, but highly asymmetric. Just 6 per cent of Australians but 17 per cent of Indonesians say that a conflict is very or extremely likely; the Indonesian result is almost three times that of the Australian figure, but still the least likely conflict according to both Australian and Indonesian respondents.

India-Pakistan

The 2017 survey included an item asking about conflict between India and Pakistan, reflecting the inclusion of India as one of the countries surveyed. Indian respondents see an India-Pakistan conflict as the most likely of the seven conflicts nominated, with 48 per cent of respondents assessing conflict as very or extremely likely. Thirty one per cent of Indonesian respondents also made this assessment, but fewer than 20 per cent of other countries’ respondents did. While Indians see an India-Pakistan conflict as the most likely of the seven, an India-Pakistan conflict ranked fourth in Australia and Korea and third in China, Indonesia and Japan.

Both Indian and Indonesian respondents are more likely to believe a serious military conflict would escalate between India and Pakistan than the other countries surveyed; 48 per cent of Indian respondents and 32 per cent of Indonesian respondents believe conflict is likely. In contrast, far fewer Australians (17 per cent), Chinese (14 per cent), Japanese (17 per cent), and South Koreans (15 per cent), believe that conflict is likely on the subcontinent.

Nationalism and isolationism

The 2017 survey included measures of nationalism and isolationism used widely in the social sciences.

Nationalism is measured using a scale constructed from responses to the following seven items.

Each item has four response options, ranging from very important to not at all important.

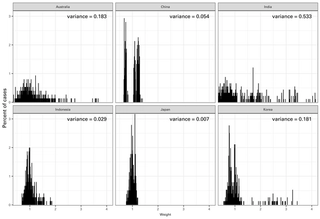

Factor analysis of these seven items suggests a two-factor solution, corresponding to an “ethnic nationalism” and a “civic nationalism.” A score was derived for each respondent on the “ethnic nationalism” dimension, dominated by responses to the items about country of birth, ancestry, residence and religion. The resulting scale measure was normalised to have mean zero and standard deviation one; negative scores correspond to relatively low levels of nationalism, conversely for positive scores. The factor analysis pooled the data across the six countries surveyed, ensuring that the nationalism scale measure is comparable across all countries.

Figure 13 displays the distribution of nationalism scores by country. Indonesia has the highest nationalism scores, followed by India; both countries have a large spike in the distribution of nationalism scores at the high end, driven by the fact that a large proportion of respondents in Indonesia and India gave extremely nationalistic responses to the underlying survey items (country of birth ancestry, residence, language, religion). China is the third most nationalistic country in the data with an average nationalism score of .27. Japan, Korea and Australia have average nationalism scores of -.27, -.34, and -.67, respectively. Not only does Australia have the lowest levels of nationalism, there is virtually no one in the Australian data reporting nationalist attitudes with the same ardency and consistency seen in the “spikes’’ in the Indonesian, Indian or Chinese data.

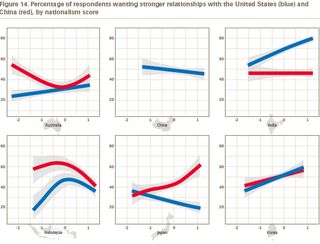

Nationalism and support for engagement with the United States and China

Nationalism is related to other important political attitudes and policy preferences in many interesting ways. Figure 14 displays the association between wanting a closer relationship with either the United States (blue line) or China (red line) and nationalism (horizontal axis). In every country except China and Indonesia, higher levels of nationalism predict a desire for a stronger relationship with the United States.

The relationship between nationalism and the desire for stronger relations with China is more complicated.

In Japan and Indonesia, increasing levels of nationalism predict less desire for closer ties with China. In Japan, this pattern is virtually the mirror-image of the relationship with respect to the United States: high levels of nationalism predict a strong desire for closer ties between Japan and the United States, but falling levels of support for closer ties between Japan and China. In Indonesia, as nationalism increases, the desire for stronger ties with either the United States or China tends to fall, with a marked preference for stronger ties with China over stronger ties with the United States among Indonesian respondents scoring low on nationalism.

Nationalism predicts a desire for stronger ties with both China and the United States in Korea, but not in India, where nationalism is unrelated to a desire for stronger ties with China. Among Australian respondents with low levels of nationalism, a majority report wanting stronger ties with China, but just one quarter report wanting stronger ties with the United States. Increasing rates of nationalism see less enthusiasm for closer ties with China among Australians, such that at median-to-high levels of nationalism in Australia there are only small and statistical differences between rates of wanting closer ties with China and with the United States.

In summary, low levels of nationalism see a divergence between preferences for closer ties with the United States and China in Australia and Indonesia: in both countries, low levels of nationalism are associated with a preference for stronger ties with China over the United States. In India and Japan, this pattern is reversed: high levels of nationalism are associated with a clear preference for stronger ties with the United States than with China.

Isolationism

Isolationism was measured by asking respondents if they agreed or disagreed with the proposition: “This country would be better off if we just stayed home and did not concern ourselves with problems in other parts of the world.’’ Results are presented in Figure 15. Australia and India are the most isolationist countries of those surveyed, with 43 per cent of Australians and half of Indians agreeing with the proposition. Isolationist sentiment runs low in the other four countries. Just 18 per cent of Chinese respondents agree with the isolationist proposition. Korea, Japan and Indonesia are intermediate cases, with 23, 30 and 26 per cent respectively of respondents in those countries reporting agreement with the isolationist proposition.

Free trade agreements

Attitudes towards free trade are summarised in Figure 16. Favourable attitudes prevail in all countries surveyed. Korea is the country most predisposed towards free trade, with 63 per cent of respondents favouring free trade and just 7 per cent opposing, for a net positive score of 56 per cent. India, China and Japan follow, with net positive scores of 52, 48 and 40 per cent respectively. Australians are the least predisposed towards free trade, with a net positive score of 29 per cent. Twenty per cent of Australian and Indonesian respondents reported opposing free trade agreements, the highest rates of opposition observed.

Foreign investment in infrastructure

Respondents were asked about attitudes towards foreign investment in infrastructure; specifically, “foreign investment in enterprises that deliver important services in [country], such as electricity, water, transport, communications.” Responses are summarised in Figure 17. India is the country most predisposed to foreign investment in infrastructure, with 67 per cent of its respondents approving and just 15 per cent disapproving, for a net positive score of 52 per cent. China and Indonesia are also positively disposed towards foreign investment in infrastructure, with net positive scores of 29 and 13 per cent respectively. Korea, Japan and Australia are negatively disposed towards foreign investment in infrastructure, with net negative scores of -18, -20 and -36, respectively. Australian opposition to foreign investment in infrastructure is especially pronounced, with 54 per cent of Australians reporting that this type of investment is bad (32 per cent) or very bad (22 per cent) for Australia, the highest rates of opposition across the counties surveyed.

Importance of democracy

Respondents were asked “how important is it for you to live in a country that is governed democratically?” Responses are on a 10-point scale, mirroring an item asked on the World Values Survey and other international survey projects. Figure 18 displays the distribution of responses by country. Responses tend to cluster around the high end of the scale in almost every country except Indonesia, where a score of 8 is the most common response. Australians have both the highest average score (8.4) and the highest propensity to give the maximum score of 10 (45 per cent) while 41 per cent of Chinese respondents responded with a score of 10, the second highest rate among the countries surveyed. China’s average score of 7.9 is the same as India’s average score and higher than Japan’s average score of 7.5 with 25 per cent of Japanese respondents answering with 5 or lower, and Japan’s average score at 7.5 being the lowest of the countries surveyed.

Figure 19 displays the average rating given to the importance of living in a country governed democratically, smoothed by age. There is no meaningful relationship between age and support for the importance of democracy in India, Indonesia and Korea, but there is a pronounced age gradient in Australia and Japan, with younger respondents much less likely to report democracy being important than their older compatriots. There is a two-point movement over the age distribution in both Australia and Japan. Older Chinese respondents are less likely to report democratic governance as being important, with about a one point shift across age cohorts aged 50 to 75 (those old enough to remember the Cultural Revolution), but no meaningful variation below the age of 50. Interestingly, Australians under the age of 40 report the same importance of democracy as do all other countries, including China, but not Japan. The high, overall, average ratings for democracy reported by Australians are largely driven by the near-universally high importance of democracy reported by older Australians.

Australia

Authors: James Brown, Research Director and Adjunct Associate Professor, United States Studies Centre at the University of Sydney and Kim Beazley, Director and Distinguished Fellow, Perth USAsia Centre at The University of Western Australia

Introduction

This survey is the first to substantially stress test the Australian public’s thinking on the American alliance and its interaction with the geopolitics of our region since the election of the Trump administration. It is essentially a measure of the effect of Trump’s campaign and the very early days of his administration, given it went to field in February this year. At that point, the Trump campaign’s scepticism of traditional United States alliances in Asia was making way for reassuring remarks from Secretaries Mattis and Tillerson, hewing US foreign policy towards a more establishment perspective. The testy first contact between President Trump and Prime Minister Turnbull, and indeed the affectionate commemorations and alliance endorsements of the Coral Sea anniversary dinner on board USS Intrepid in New York, both occurred after this survey polled respondents.

Trump, during the campaign as now, is deeply opposed to institutions and practices that constitute the post-World War II, US-guaranteed, global economic environment. This view has the potential to roil trading arrangements between most of the countries in this survey. Similarly, Trump’s instinctive approach to international security is premised on the unstinting application of military power when United States interests are engaged. His outreach to China to foil North Korea’s nuclear objectives is interlaced with the threat of military action should diplomacy fail. Australia is a trading nation, globally engaged, and dependant for its security and prosperity on the stability of the international system. Australians are a watchful people on these aspects of our circumstances and do not welcome a strategy of disruption. Intuitively one would expect a Trump Administration to heighten concerns of the Australian public about the trajectory of US power and influence in the region. This first cut of opinion verifies that.

But in Australia there is recent concern about China’s role in the region and influence on this country. In the past 12 months, there has been an increasingly visible and wide-ranging debate on Chinese soft power in Australia, prompted largely by revelations about the extent and nature of Chinese donations to Australian politicians. There have been various efforts to catalogue the extent of Chinese soft power initiatives and influence in Australian media, schools and universities, and political institutions. There has been a number of closely reported arrests of Australian academics and business people in China. Similarly, there has been a number of decisions rejecting Chinese state investment into Australian companies on national security grounds: the August 2016 decision by the Australian Government to reject the acquisition of electricity network Ausgrid by China’s state-owned State Grid Corporation being the highest profile.

There is currently some degree of flux in Australian public opinion regarding both the United States and China, strategic currents in Asia, and Australia’s place and role in the region. In the Australian federal election held on 2 July 2016, few of these issues were decisive. This is typical of the low priority Australians have traditionally accorded to national security and foreign policy issues at election time. However, since that election there have been disparate points of political emphasis on some of the issues canvassed in this survey, notably free trade, foreign investment, United States leadership in Asia and immigration. A note of caution on the sample is worthwhile here before interpretation of its findings. When questioned on their vote at the last election 29 per cent of Australians recorded for the Coalition; 34 per cent for Labor; 7 per cent for Greens; 15 per cent for other parties, while 15 per cent voted informal or did not vote. This suggests a slight weighting of the poll toward the centre left.

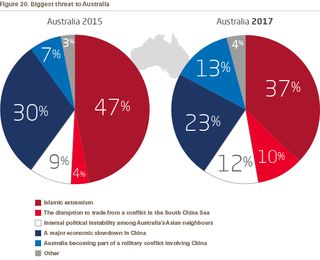

The big questions on the alliance

Australia’s American alliance was conceived in and is sustained by a search for reassurance in a strategic environment perceived as threatening, at least potentially, to Australian security and wellbeing. There has been some change in how Australians perceive their security from 2015 to 2017 (Figure 20). In 2015, 47 per cent of Australian respondents judged the major threat to the country to be Islamic extremism. That has now (in 2017) dropped to a still very high and dramatic 37 per cent, though this is perhaps less noteworthy than might be thought. The re-prioritisation of threat perceptions is entirely covered by an upgrading of possible conflict with China; a rise from 4 to 10 per cent in those concerned with the disruption of trade from a conflict in the South China Sea; an increase of 7 to 13 per cent in Australian respondents concerned about involvement in a military conflict with China. These numbers remain low but the movement is apparent. Australians this year again overwhelmingly characterised the US-China relationship as a competitive one. During the Obama administration, the United States had many disagreements with China, yet its overwhelming focus was to contain them through diplomatic engagement underpinned by intense, structured activity. The early stages of the Trump administration, by contrast, stressed “unfair” trade competition with China and a need to enhance the United States’ military profile in the region. One possible interpretation of the evolved threat perceptions apparent in this survey is that Australians have formed a slightly dimmer view of the likely outcome of strategic competition between the United States and China.

Asked whether the alliance made the biggest threat more likely, Australian respondents showed limited movement from the 2015 survey, mostly well within the polling margin of error; 39 to 40 per cent on the “likely” front; 50 to 54 per cent on the “no difference” default position. There was a small though significant shift in those stating that the alliance makes major threats to Australia less likely: 11 per cent down to 6 per cent. One wonders at the content of the biggest threat in the mind of these respondents. Given the drop in the perception of the Islamic extremist threat but the relative stability in all but the last number it seems likely that the latter have China-US relations in mind.

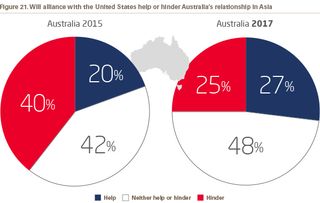

In that light, the answers to the question of whether the alliance helps or hinders Australia’s relationships in Asia (Australian respondents identified us an Asia-Pacific nation two to one in both polls) are somewhat counter intuitive. The “helps” group moved from 20 to 27 per cent and the default, “neither helps nor hinders,” from 42 to 48 per cent (Figure 21). The “hinders” group dropped from 40 to 25 per cent. These are big movements on big numbers. They suggest that whatever Australian respondents might feel about a general movement in strategic weight against the United States, they are not concerned that the alliance will restrict Australia’s ability to navigate the new strategic environment. This is amplified by the fact that of the 25 per cent who see the alliance as hindering Australia’s relationships in Asia, 19 per cent see it as doing so only a little.

Which leads to the critical question of support for United States access to Australian defence facilities. “Allow military bases or increased access” responses stayed at 24 per cent; the default, “keep the same access” at 59 per cent; and “decrease or remove” at 18 per cent. Perhaps in the answers to this series of questions about threats, the impact of the alliances and defence access we might expect to see movement on the next survey. The trajectory of US policy in Afghanistan, Iraq/Syria and Korea may well produce a greater ask of Australia. While support for the alliance and US-Australian defence connections have been remarkably resilient through US administrations with jarring policies, the disconnection of the Trump administration from the verities of its post-World War II global stance might begin to impact as attitudes translate into policies and actions.

Continuities and discontinuities

Looking more broadly at the region, there are some discontinuities in Australian perceptions between 2015 and 2017. The difference this year is that the gap between Australia and the other regional countries surveyed has closed. China is overwhelmingly perceived by them as much more influential, a reaction perhaps to deep uncertainties in Japan and South Korea arising from the Trump campaign’s dismissal of US Asian alliances and criticism of trading relationships. Australians remain even handed on whether or not the United States and China do “more good than harm” in our region; on the United States 18 per cent “more good,” on China, 20 per cent “more good.” On harm, 31 per cent see the United States as “harmful” and 30 per cent China. The default position on the trend line on the United States, “about the same” is 51 per cent, on China 50 per cent.

On the value of trade with China and the United States, Australians are overwhelmingly and basically equally in favour of its impact. Likewise, Australians are favourably disposed to free trade agreements.

Overwhelmingly Australians perceive the United States as the global rule setter: 71 per cent the United States, 11 per cent China, 5 per cent Russia and 12 per cent some other. The institutions that are part of those rules, the United Nations, the International Monetary Fund and the World Trade Organization, are viewed more sceptically: “effective”’ 31 per cent; “ineffective” 29 per cent and “neutral” 40 per cent. Chinese opinions have much more confidence in these institutions: “effective” 66 per cent, “ineffective” 29 per cent and “neutral” 23 per cent.

On the value of trade with China and the United States, Australians are overwhelmingly and basically equally in favour of its impact. Likewise, Australians are favourably disposed to free trade agreements: 49 per cent “in favour,” 20 per cent “opposed” and 31 per cent “neutral.” On investment, we diverge: on investment from China, 26 per cent see it as “good,” 38 per cent “bad” and 26 per cent “neutral.” In the case of investment from the United States, 35 per cent “good,” 23 per cent “bad” and “neutral” 42 per cent.

The one question in the survey which clearly focuses on the Trump Administration reveals the challenge before Australian policy makers. It also indicates the possibility that the numbers we are dealing with in this poll may change substantially over the next year. This is particularly so when one considers how little of an experience with Trump is caught up in this survey.

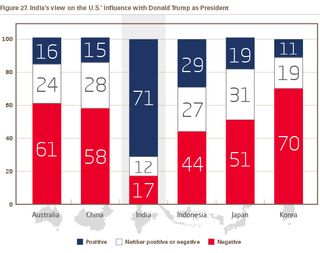

The question seeks answers on how positive or negative his impact will be (Figure 22). “Positive” records 16 per cent, “negative” 61 per cent, “neutral” 24 per cent (rounded out figures). These are very bad numbers indeed. They suggest these sentiments have only had a marginal effect so far on the other numbers discussed. The next survey will reflect actual experience of the administration, as opposed to perceptions of the president and his campaign rhetoric. One is reminded of the answer given by late prime minister Harold MacMillan of Britain when asked what would determine the outcome of the next election: “events, dear boy, events.”

Further questions

Beyond considering what an Australian sample more experienced with the Trump administration might conclude on the issues canvassed here, there are two issues that arise in this poll worthy of further consideration. The first is how Australian sentiment might change should there be an increased Chinese military presence in the Asia-Pacific. Australian responses to regional security questions and the issue of US-China strategic competition in Asia seem to draw to the ambivalent centre for now. One explanation for this might be that Australians see themselves as somewhat separate, or insulated, from the strategic dynamics of Asia. We did not ask for responses to this specific question, but responses to the question as to whether Australia should pursue an isolationist response indicate that 57 per cent of Australians would reject this approach, suggesting instead a preference for active Australian engagement in and with the Indo-Pacific region. Australians also record a relatively benign view overall of the potential for conflict in the Indo-Pacific. But when presented with a starker question regarding the desirability of Chinese military presence in the region, Australian responses are quite strong: 43 per cent would like to see a lower Chinese military presence. That’s greatly at odds with Chinese respondents, of whom nearly seven in ten would like to see an increased presence of their own military forces in the region. Those same respondents overwhelmingly supported (82 per cent) an actively engaged role for China in the Indo-Pacific. The Australian public debate mostly focuses on the economic aspects of China’s re-rise in the region: it would be interesting to understand how Australian sentiments might change in this survey and others were the role of China in the region to be more predominantly framed as a security or military issue.

The second issue worthy of further examination is Australian views on the utility and relevance of alliances. Australian officials are prone to speak of the Australian-American alliance (ANZUS) ahead of the Australian-American relationship; that is the instrument of the alliance frames narratives of the bilateral relationship. This survey shows that Australians believe the US alliance guarantee to Australia is credible — 93 per cent believe that in the event of a crisis America would come to Australia’s aid. Yet a majority of Australians believe that the alliance makes no difference to the major threats that Australia faces, and half as many respondents this year as last believe that the alliance reduces the likelihood of threats to Australia (6 per cent down from 11 per cent in 2015). Only one in four of respondents (27 per cent) believe that the US alliance is an asset to Australian engagement in Asia, though as previously mentioned fewer Australians this year are inclined to conclude that the alliance hinders Australia’s relationship with Southeast Asia specifically. Australians generally show a poor awareness of other US alliances in Asia, and in this survey at least are less likely than other countries to see the United States as actively engaged in regional institutions. It seems that Australians see little utility resulting from alliances themselves, or at least their alliance with the United States. Certainly, it would be interesting to probe more deeply Australian understandings of what an alliance entails, particularly during periods short of war. And to probe what understanding Australians have of the ways that alliances can stabilise Asia during times of peace. This would seem critical work given the way that discussion of the alliance dominates the US-Australia relationship.

China

Author: Dr Shao Yuqun, Executive Director, Shanghai Institutes for International Studies[1]

General positive evaluation of China’s overall development and its influence

In general, the Chinese respondents were quite satisfied with China’s regional influence, both in 2017 (43 per cent) and in ten years’ time (74 per cent). Most think that China’s influence in the region and on other regional countries has been positive although respondents from some other regional countries such as South Korea, Japan and India perceived China’s influence somewhat negatively. Sixty six per cent of Chinese respondents believe current global institutions like the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the World Trade Organization are effective and they are optimistic about China’s capability of setting rules for international affairs. One new phenomenon is that Chinese respondents’ concern about North Korea or South Korea starting a conflict has risen markedly. However, overall, the Chinese respondents are quite optimistic about the future peace of the Asia-Pacific region, as evidenced by their concerns about possible conflicts between China and Japan, South Korea and North Korea, and China and the United States, which have declined dramatically.

Chinese respondents’ generally positive attitude can be explained from the following perspectives. First, while the speed of China’s economic development has slowed to be the “new normal” it is characterised by structural change, better growth and emission reductions, with stability that is meeting people’s expectation. The Chinese central government has made great efforts to create jobs for young people, fight corruption, address the challenges of environmental pollution in the cities, transform the economic structure and narrow the gap between rural and urban areas. The government’s policies are being well received by the Chinese people.

Secondly, China’s foreign policy is promoting China’s relations with the regional countries and serving its national interests. Seventy four per cent of Chinese respondents support China’s developing economic and trade relations with regional countries and believe China’s influence in the region will increase in the future. With its developing capacities on all fronts, China can contribute to the security and development of the region and the world and the successful creation of the Asian Infrastructure and Investment Bank (AIIB) is testimony to that belief.

Thirdly, China has been a contributor to the current international order which has been established since World War II. Since China adopted reform and open policies at the end of the 1970s and progressively joined the institutions named above, its economic and social developments have been huge, and have not only drawn attention from all over the world, but most importantly, have helped ordinary Chinese people get rid of the feeling of 100 years of humiliation. Though some unfairness towards developing countries, especially regarding the setting of rules is still obvious, and the Chinese government has expressed its dissatisfaction and criticism publicly, and is pushing to reform these institutions, it has never tried to build a new international order.

Fifty eight per cent of Chinese respondents believe that the influence of the United States in the Asia-Pacific region will decline in the next five years.

Fourthly, at the conclusion of the survey respondents believed the Asia-Pacific region has maintained peace and stability. China has continued its policy of peaceful development and although there are some difficulties with relations between and among certain parties, the possibility of military conflicts is low. Since Tsai Ing-wen came to power in Taiwan in 2016 the cross-Strait relationship has entered into a phase known as “cold peace.” This means the narrow sense of status quo of the relationship has been broken because the Tsai administration has not recognised either “One China” or the “1992 consensus” which is the political foundation for the peaceful development of the cross-Strait relationship. However, the broad sense of status quo is still there as the Tsai administration has learned lessons from the Chen Shuibian administration from 2001 to 2008 and has not sought constitutional independence. China’s relationship with Japan has been stable, albeit on a low level last year. While no hotspot or crisis has occurred, so far there have not been many signs of improvement of this bilateral relationship. It is noteworthy that since the disputes on the Korean Peninsula have become tense, the number of Chinese respondents concerned that either North or South Korea will start a conflict has increased by 11 and 17 per cent respectively. This reveals that the legacies of the Cold War are still a threat to regional security and need to be managed carefully by all concerned parties.

Interestingly, the perception of Chinese respondents on China’s role in the Asia-Pacific region differs slightly compared with some other surveyed countries, especially South Korea, Japan and India (Figure 23). Due to the cold relations between China and Japan it is not surprising that 71 per cent of Japanese respondents continue to see China’s influence more negatively. It is a pity that a growing number of South Korean respondents surveyed this year think China has a more negative influence on South Korea than the previous survey. A possible reason for this is because China has strongly criticised the South Korean Government’s acceptance of the deployment of the US anti-ballistic missile system Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) in its territory, and in some Chinese cities citizens have angrily boycotted products related to the Lotte Group, a South Korean/Japanese conglomerate which offered land to the South Korean Government for the deployment of THAAD. Another possible reason for the worsening image of China among South Korean people is China’s policy towards North Korea. India, as a new member of this survey group, has shown a somewhat negative attitude towards China. This may be explained by the popular views in India that China does not support India’s ambition to be a global power, China takes a pro-Pakistan position regarding disputes between India and Pakistan, and China has been frequently challenging India’s control in the disputed territory between it and Pakistan.

Perception of the US role in the region

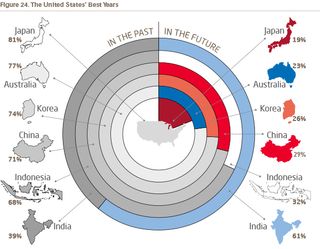

The overall Chinese respondents’ perception of the US role in the Asia-Pacific region has not changed from the results of the last survey (Figure 24). A majority of Chinese respondents think that the influence of the United States is declining and will continue to decline in the future. Forty three per cent of Chinese surveyed think that the United States does more harm than good in the region and regardless of whether President Trump was or was not mentioned in the questionnaire, 58 per cent of Chinese respondents believe that the influence of the United States will decline in the next five years. This result is quite different compared to the results of US allies in the region, and show that some respondents have no confidence in President Trump, whose behaviour and attitude towards the US allies were considered to be extreme during last year’s election campaign.

Interestingly, more than 40 per cent of the Chinese respondents were mistaken in believing that the United States was a member of regional institutions, such as Association of Southeast Asian Nations, AIIB, Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership and East Asia Summit.

The reasons for this could be interpreted from the following two angles. On one hand, the Obama administration’s Rebalance to Asia and the Pacific strategy was seen by most Chinese as a threat to China’s interests in the region. Though the Obama administration had repeatedly said that the Rebalance strategy was more of a hedging policy, ordinary Chinese still believed the strategy aimed to contain China. For example, the United States is not a concerned party in the so called South China Sea issue and the territorial and sovereign disputes are between China and some other regional countries, but the South China Sea arbitration case initiated by the Philippines was planned and supported by the Obama administration. Hence the South China Sea issue was perceived to be a tool for the Obama administration to exert its influence in the region. Some Chinese people also believe that the United States has been hypocritical since it has never accepted an international court’s ruling when it infringed sovereignty or territorial interests while it asked China to do so.

Additionally, the US decision to deploy THAAD in South Korea has angered some Chinese people. The North Korean nuclear issue has been in place for decades but when the situation started to get tense in 2016, the United States decided to deploy THAAD in South Korea. According to the Chinese official statement and academic research, THAAD cannot offer security protection for South Korea in the face of a North Korean nuclear or conventional military threat, but will put China under United States military surveillance. To the Chinese this is another example of the Obama administration trying to narrow China’s strategic space in the Asia-Pacific region.

The relatively high number of Chinese respondents who wrongly held the perception regarding US participation in regional institutions and the UNCLOS[2] can be explained in two ways. One is that recognition of these institutions in China is relatively low, either because of their ineffectiveness in regional affairs, or the lack of reports about US policies towards these institutions by the Chinese media. The other is that ordinary Chinese are more geostrategically-focused and pay less attention to international law or regional institutions.

Perceptions of the China-US relationship and its future development

Overall, 75 per cent of Chinese respondents support maintaining the current status of the bilateral relationship, or to strengthening it in the future, which means that the majority of Chinese people understand the importance of the relationship, not only for China, but for the region too. They support developing economic and trade relations with the United States, with two figures worthy of special attention. Forty three per cent of the Chinese respondents think that a China-US conflict is not at all likely while 5 per cent think that the conflict is very likely. Comparing these results with 27 and 12 per cent respectively for the last survey, it is a positive sign for the future of this bilateral relationship.

Some Chinese respondents have referred to domestic matters such as the increasing political divide within the United States and its huge debt, but the majority of respondents regard the biggest challenge for the United States to be China’s economic development (29 per cent).

The survey results indicate that 45 per cent of Chinese respondents realise that China and the United States do not have to fight each other, since neither can afford a military confrontation between two nuclear countries.

With the US presidential elections occurring in November 2016, both campaigns attracted much interest in China. This was partly because the Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton was very well known in China and the Republican candidate Donald Trump had an image of being a loud-mouthed, anti-establishment, successful businessman. Donald Trump has since become quite popular in China where he is seen by many Chinese as a good deal maker without an ideological bias. At the same time, due to a more mature understanding of the US political system and its domestic politics, Chinese people understood that the campaign rhetoric was different to real policy options. The presidential candidates criticised China and made China a scapegoat for domestic political reasons, however, once a candidate is in the White House, they understand the importance of a stable US-China relationship and return to the framework that previous US governments have strengthened.

The survey results indicate that 45 per cent of Chinese respondents realise that China and the United States do not have to fight each other, since neither can afford a military confrontation between two nuclear countries. Nor do they accept the theories raised by some international relations experts or the media, that sooner or later, a rising power (China) will challenge the established power (United States) militarily.

China’s increasing power was seen by 39 per cent of Chinese respondents as the biggest source of conflict between China and the United States, which is much higher than the South China Sea issue (19 per cent) and the Taiwan question (16 per cent). The results also indicate that many Chinese respondents think that the Rebalance strategy adopted by the Obama administration was to hedge, if not contain, the rise of China.

Perception of China’s future

Generally, Chinese respondents are quite confident and optimistic about China’s future (Figure 25). Seventy six per cent of Chinese respondents believe that China will eventually become a superpower. Eighty two per cent of Chinese respondents believe that China should pursue an internationalist engagement with the world; this is strikingly the highest among all the surveyed countries. The confidence about the future is based on respondents’ satisfaction with the current status of their country and their strong belief in the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation. On one hand, although China has met many challenges on the economic and social fronts, the policies adopted by the central and local governments have been quite successful in maintaining peace, stability and economic growth. On the other hand, the violence after the Arab Spring in some Middle Eastern countries, together with the rise of populist forces in Europe and the United States have become negative examples to Chinese citizens that democracy does not necessarily bring good governance and that China should continue to develop ways that are based on its own experiences and with its own characteristics.

Seventy six per cent of Chinese respondents believe that China will eventually become a superpower.

Perhaps because the Chinese respondents are satisfied with China’s current status and they still consider they are beneficiaries of globalisation, 56 per cent welcome foreign investment into China’s own infrastructure building. Fifty five per cent support signing free trade agreements with other countries and 49 per cent think immigration is good for the economy. This attitude is quite different to the developed economies in the region.

While they are more open to economic globalisation, culturally the Chinese respondents were more sensitive about safeguarding their own traditions and cultural roots. Forty one per cent worry about the Chinese culture being harmed by immigrants; 91 per cent think it’s important to “feel” Chinese and respect political institutions and laws; 71 per cent think it’s important to be followers of national religion(s);[3] and 86 per cent believe it is important to have Chinese ancestry. Perhaps an explanation for these beliefs could be found in China’s long history. The Chinese have a strong commitment to their traditions and the Chinese culture has always been strong enough to absorb the outside cultural factors. The strong influences of globalisation have not changed that so far.

India

Author: Dhruva Jaishankar, Fellow, Brookings India

India stands at an important juncture today. Its central government has probably its strongest political mandate since the 1980s, and arguably since the 1970s. The country’s economic growth is going well by global standards, but with considerable room for improvement. It has also become more diplomatically active with unprecedented cooperation with the United States and Japan, continuing defence relations with Russia, complex security and economic ties with China, and new forms of outreach and engagements in its immediate neighbourhood, the Indian Ocean, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East. Today, the rest of the world matters more for India than ever before. India’s trade-to-GDP ratio is higher than China’s or the United States’, it is the world’s largest defence importer, it has a large diaspora that is a major source of investment and remittances, and it is among the most dependent major economies on energy imports.

Despite these developments, the understanding of how the Indian public perceives international developments is poor, with few large-scale, face-to-face or telephone surveys conducted outside major metropolitan areas. Many surveys also display a lack of awareness or opinions about international issues. The latest survey helps to fill the gap in understanding of public Indian attitudes concerning the United States, China and the international system; India’s role and relations with Pakistan; Indian identity and democracy; and perspectives on trade, investment and immigration.

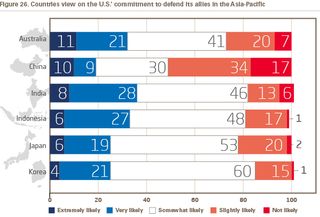

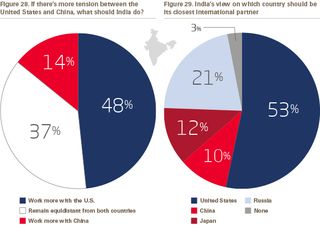

The United States, China and the Asian Order

Perhaps the most striking takeaway from the survey is that the Indian public remains overwhelmingly optimistic about the United States with 52 per cent believing it has more influence in Asia than it did ten years ago, and an astounding 61 per cent believing that the United States’ best years are ahead of it. This is in contrast to responses from the five other countries polled, where only between 19 and 32 per cent believe the United States’ best years are in the future (Figure 26). The survey revealed that 53 per cent of Indian respondents would like to see an increased US military presence in Asia, and 82 per cent believe that the United States is somewhat, very, or extremely likely to keep its alliance commitments in the region. Most tellingly, 52 per cent of Indian respondents believe the United States does more good than harm, which is very favourable compared to 18 to 36 per cent among US allies such as Australia, Japan and South Korea. By contrast, given the large number of Indian elites who now study in the United States, Indian respondents showed a lower preference (32 per cent) for going to university there over their home country — if costs were the same — than respondents from China (61 per cent), South Korea (46 per cent) and Indonesia (35 per cent).

The Indian public remains overwhelmingly optimistic about the United States with 52 per cent believing it has more influence in Asia than it did ten years ago, and an astounding 61 per cent believing that the United States’ best years are ahead of it.