Preface

Australia’s long-standing strategic relationship with the United States is transforming. Two factors are driving this change.

First is the pace and intensity of global geostrategic change centred on the Indo-Pacific. Not since the Second World War has Australia found itself so proximate to shifts in national power and capability, nor with as much at stake. Technological changes and economic interdependence have reshaped the nature of interstate competition. Projections of state power take a myriad of forms, presenting Australia strategic challenges and opportunities across multiple domains.

Second, the United States remains consumed by a fractious debate about its role in the world and almost paralysed by disunity. While policy elites from both sides of American politics aspire to make the Indo-Pacific the primary geostrategic focus of the United States, policy detail and tangible action is slow to emerge. Domestic politics, Europe and the Middle East compete with the Indo-Pacific for US strategic and operational focus. This was true under the Obama administration, the Trump administration and remains our assessment today, just over a year into the Biden administration. The Quad and AUKUS are welcome and positive developments, but work is still needed to realise their potential for contributing to Australian security and prosperity.

As we complete this volume, Russia has invaded Ukraine and the mettle of US alliances are being tested in ways not seen since before the Cold War. Because Australia’s relationship with the United States is its most important strategic asset, the US focus and pull towards Europe carries significant implications for Australia. The attitudes and sentiment we surveyed in our polling predate this conflict, but provide important insights into how the American people may react and, therefore, inform the Biden administration’s approach toward juggling international challenges while facing a crucial domestic election.

This volume, State of the United States: Biden’s agenda in the balance, analyses these drivers for change and the resulting implications for Australia. Consistent with the Centre’s mission, we build on this analysis to advocate a positive potential for advancing an agenda for the US-Australian alliance in this critical phase.

Professor Simon Jackman

Chief Executive Officer

March 2022

Executive summary

Where the United States was a year ago

In January 2021 alone, a deadly insurrection overtook the US Capitol for the first time in US history, a record 96,654 Americans died from COVID-19, and Joseph R. Biden Jr became the 46th president of the United States.

A few weeks later the United States Studies Centre (USSC) published its inaugural State of the United States, with the theme “An evolving alliance agenda.” Key elements of that report were:

- Predicting that as much as Australia might have feared becoming a target of the Biden administration’s climate agenda, US political realities would “limit broader congressional legislation on climate change” and that such differences would “not in any way threaten the deep fundamental relationship between the two countries” because the administration’s efforts would mostly be limited to executive orders and rhetoric. This insight has proven correct.

- Cautioning that trade would “not be an urgent priority for the administration relative to domestic issues” since actualised by the Biden administration leaving intact much of the Trump administration’s protectionist and inward-focused trade policies.

- Urging Australia to pursue “innovative ways to advance defence industry integration with the United States, including by coordinating with Canada and the United Kingdom” — the sort of integration now sought through the AUKUS agreement.

- Warning that ever-deepening political polarisation would constrain much of the Biden administration’s ambitious agenda to a few key areas: an infrastructure package as well as domestic and defence investments, which help the United States compete with and better address the China challenge.1

When asked at the launch event for State of the United States in March 2021 how the US Government envisioned a pathway for an ambitious Biden administration agenda amid such overwhelming political unrest, the State Department’s Deputy Assistant Secretary of State Atul Keshap posited that, “America is a society that is constantly innovating and reinventing itself. We’re kind of like that wobble doll, where you punch it and then it sort of wobbles back at you. There’s a lot of resiliency.”2

Keshap’s optimism mirrors that of Joe Biden himself, who famously said while campaigning for president in 2019 that Republicans would have an “epiphany” and turn away from Donald Trump once he was out of office.3

Alas, our analysis leads us to a different conclusion, and one with some bracing implications for Australian policymakers and strategic thinkers.

The State of the United States in 2022

This year’s State of the United States makes clear that, contrary to the optimists’ hopes, America has neither “wobbled back” nor experienced any epiphanies.

A year after what many considered one of the darkest periods in US history sees the United States experiencing the worst inflation in 40 years, more US deaths from COVID-19 occurring during the Biden administration than the Trump administration, the prospect of the biggest European land war since the Second World War, and the capital cities of its closest allies experiencing “American-style” protests over personal freedoms — Australia included.

Despite several important accomplishments in their first year in office, much of the ambitious Biden agenda remains unfulfilled, with the administration’s political capital exhausted.

Our State of the United States volume for 2022, “Biden’s agenda in the balance,” concludes that despite several important accomplishments, much of the ambitious Biden agenda remains unfulfilled, with much of the administration’s political capital exhausted.

The Biden administration’s achievements to date should not be understated. In 2021, the United States saw:

- more than 200 million Americans fully vaccinated, reducing their risk of serious death or illness from COVID by orders of magnitudes;4

- a record number of new jobs and economic growth following the passage of a US$1.9 trillion COVID recovery package in March 2021;5

- a 30 per cent reduction in child poverty;6

- unprecedented coordination with US allies, most notably the ground-breaking formation of AUKUS as well as an expansion and deepening of the Quad’s remit;

- a US$1.2 trillion bipartisan infrastructure package passed in November — the first major infrastructure legislation to pass in decades;

- and a return to global leadership on combatting climate change.

Despite such achievements — or even because of them — our research reveals a United States deeply divided, increasingly isolationist and pessimistic, undergoing substantial democratic backsliding and at risk of more. Specifically:

- The United States has fallen out of the top 30 liberal democracies, a trend that continues as many Republican-controlled states enact laws making voter registration and turn out burdensome and election administration subject to partisan interference.

- Our original survey research finds that even those who voted for Joe Biden in 2020 are now just as pessimistic about the future of the United States as they were during the Trump administration, while the Republicans’ preferred candidate for the 2024 presidential election remains Donald Trump.

- And, having begun his presidency with a majority of Americans approving of his performance, Biden’s approval ratings in the low 40s are indistinguishable from President Trump’s at the same point in his tenure in office. Amid such pessimism and low approval ratings, President Biden faces the exceedingly likely prospect of his party losing control of both houses of Congress in the November 2022 midterm elections.

Beyond President Biden’s political headwinds, our survey finds that the United States faces deep partisan disagreements as to what problems America faces at home and abroad, as well as how to address them. Only half of Americans are satisfied with their democracy — compared to nearly 80 per cent of Australians.

Australians may take solace in the fact bipartisan US support for its alliance with Australia remains unwavering and the bipartisan American consensus that China is a major problem remains unchanged. Yet there is little indication Americans are convinced the Indo-Pacific is the priority region for the US Government compared to Europe and the Middle East.

Furthermore, isolationist American beliefs have steadily increased from 28 per cent in 2019 to 40 per cent at the end of 2021 while a plurality of Americans are simply unsure whether any of their alliances make them safer. This sentiment and the ubiquity of US political paralysis and dysfunction should not let Australians rest easy.

Among our key assessments of the first year of the Biden administration, a few come to the fore:

- AUKUS and multilateral regional partnerships shine: The administration’s security efforts in the Indo-Pacific prioritised correcting the course of US policy after four years of Donald Trump. Since taking office, they settled contentious defence cost-sharing talks with Japan and South Korea, revived a visiting forces agreement with the Philippines, convened the first in-person leaders’ meeting of the Quad, and expanded the Australia-US Force Posture Initiatives. But one initiative outshines the others. The establishment of the Australia-United Kingdom-United States (AUKUS) agreement in September 2021 and its flagship nuclear-powered submarine project which is now a critical model for the long-needed US approach to empowering key regional allies.

- Domestic issues dominate robust appetite for policy change: The administration came to office with an ambitious domestic economic agenda, exemplified by the largest-ever peacetime federal spending and budget deficits in its first year, though much of the agenda is yet to pass. On diverse economic issues ranging from supply chain security and innovation to trade and investment, the agenda remains inwardly focused, with domestic economic objectives, particularly a domestic industry policy, prioritised over international economic engagement.

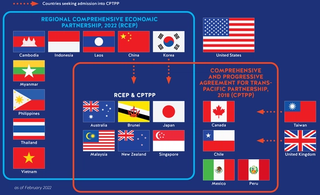

- No moves to fill the Indo-Pacific geoeconomic void, to China’s advantage: Without a doubt, the most glaring failure and consistent criticism of the Biden administration’s efforts thus far is on trade, where the United States finds itself outside the Indo-Pacific’s two most important trading blocs with little indication the administration will rectify the situation. Washington’s inability to develop a comprehensive economic strategy for the Indo-Pacific leaves vacant the rule-making space that will determine the future evolution of the Indo-Pacific and restricts the ability to compete with the source of Chinese influence on the issues that drive regional alignment preferences.

Implications and policy recommendations for Australian decision-makers

Security

Australia should seek from the United States:

- a clearer articulation of long-term US objectives vis-à-vis China;

- more focused efforts to empower regional allies;

- substantial investment in a more distributed and resilient Indo-Pacific force posture;

- greater engagement with Southeast Asian countries at the presidential level;

- an acceleration of defence industrial and export control reforms; and

- presidential leadership against domestic protectionism.

Domestic and foreign policy

The Biden administration’s so-called ‘foreign policy for the middle class,’ speaks to some of the domestic discontent tapped by Trump’s ‘America First.’ Accordingly, integrating the domestic economic agenda with industrial and technological cooperation with allies will remain one of the administration’s biggest challenges going forward. Australia should leverage AUKUS for institutionalising pathways for deeper Australian integration into the US defence industry. Ultimately, the United States should bolster allied coordination and seek to remove structural impediments to the US innovation system that would help the United States and its allies better compete with China.

Economics

On the economic front, Australia will need to continue more of the heavy lifting on regional trade developments, as it has done since the Trump administration left the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Australia should endeavour to actively shape the two major trading blocs that currently lack US participation — the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership — by making them as attractive as possible to potential US, not to mention Indian, membership in the future. This will require closer coordination with the region’s other economically developed states, such as Japan, South Korea and Singapore. Australia should also support the Biden administration’s yet to be released “Indo-Pacific Economic Framework,” shaping its final agenda to be as relevant and appealing to the region as possible.

Conclusion

In recent testimony to the Australian Parliament, the Secretary of Australia’s Department of Defence, Greg Moriarty, opined that “…Australia’s national resilience is an important contributor to our overall defence posture and national resilience depends on national unity.” Moriarty’s answer was in response to a question as to whether he concurred with the view of then Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) Secretary Frances Adamson, “when we are able to project a sense of bipartisanship and unity about what matters most in our values, that’s a powerful message.”7

On this fundamental point, our analysis leads us to a sobering conclusion: the United States lacks the national unity that leaders of Australia’s defence and diplomatic establishment view as critical ingredients of national defence.

The implication for Australia is clear. While the US alliance remains Australia’s single most valuable strategic asset, Australia must continue to rapidly evolve its own capabilities, resilience and autonomy.

Advancing Australia’s national interests demands a clear-eyed understanding of American power and resolve. This, in turn, is central to the mission of the United States Studies Centre and the purpose of the chapters that follow.

Section 1. Shifting political and social foundations of US power

Overview

by Professor Simon Jackman

Early 2022 sees the United States unable to put old issues to rest while new troubles emerge.

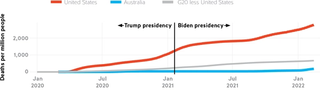

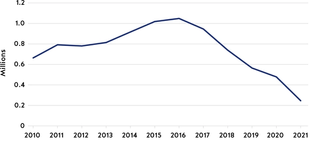

The COVID-19 pandemic ravaged the United States out of proportion to the nation’s wealth. By February 2022, the total number of lives lost to COVID in the United States is 4.2 times that seen across the rest of the G20, normalised by population (see Figure 1.1). Thus far, 940,000 Americans have died from or with COVID, the majority since Joe Biden took office in January 2021. The arrival of the Omicron variant coincided with the US winter, driving fatalities back to levels seen during last winter and the transition from the Trump administration to the Biden administration.

Figure 1.1. More Americans have died from COVID-19 during the Biden administration than during the Trump administration

Cumulative COVID-19 deaths per million people, United States, Australia and for the G20 absent the United States

The Biden administration’s ambitious legislative agenda has not been realised, frustrating the Democratic base who hoped that control of both House and Senate — and the pandemic — would provide the tailwinds for legislating a once-in-a-generation expansion of the US social safety net, infrastructure spending, and efforts to address climate change.

As we predicted in the 2021 State of the United States, a 50-50 Senate and a wafer-thin majority in the House of Representatives was always going to stymie Democrats’ ambitions. Democrats are torn between two impulses: to tread carefully, so as not to endanger marginal seats in the 2022 midterms, or alternatively to ‘go big’ and energise their base with a bold legislative agenda, and take advantage of this window of majority control in both houses of Congress.

Irrespective of how artfully Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi has managed her slim House majority, Democratic Senators Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona have been unwilling to support the more expansive and progressive elements of the administration’s agenda. Manchin and Sinema also baulked at repealing and amending the Senate’s filibuster rules that require 60 votes to end debate on many issues, the protection of voting rights key among them. Biden’s significant accomplishments — ranging from the approval of a record number of federal judges to the passing of the first major infrastructural legislation in decades — are lost in Democrats’ disappointment and outweighed both by their early expectations for success and frustration with Manchin and Sinema.

Every passing week in early 2022 brings more signs of inflation, driven by a combination of pandemic-deferred consumer demand, pandemic-recovery stimulus efforts and permissive monetary policy. This is set against pandemic-driven supply chain constraints, as well as changes in spending, working and commuting habits. For the first time in decades, Americans are worried about inflation and the “sticker shock” anxieties it induces.

Democrats are torn between two impulses: to tread carefully, so as not to endanger marginal seats in the 2022 midterms, or alternatively to ‘go big’ and energise their base with a bold legislative agenda, and take advantage of this window of majority control in both houses of Congress.

Away from home, the end of the US withdrawal from Afghanistan in August 2021 — marked by ignominy and tragedy — was a serious setback for President Biden given the opprobrium that came from across the US political spectrum. It was the first serious blow to Biden’s credentials as a competent steward of national security and international affairs. It also removed any doubt that Biden’s political honeymoon was over.

Now, in early 2022, Russian President Vladimir Putin tests Biden and NATO allies over Ukraine. Biden is under enormous pressure to simultaneously signal US commitment to NATO allies and partners, project authority and competence at home, and stand up to Putin without risking American lives.

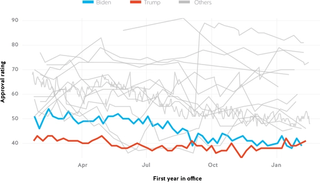

All of this weighs heavily on Biden’s standing, slowly draining his political capital as measured by his approval rating (Figure 1.2). In an era of profound partisan polarisation, US presidents seldom enter office with high approval ratings. Biden entered the presidency with approval ratings low by historical standards though still 10 points higher than Trump’s starting point. But over the course of his first year in office, Biden shed his lead over Trump and now finds himself competing with Trump for the lowest presidential approval ratings recorded at this stage of their presidencies.

Figure 1.2. One year into office, President Biden’s approval ratings have declined to Trump levels

Approval for Biden, compared with Trump and other presidents, at the same stage of their presidency

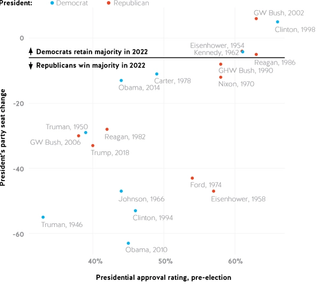

This erosion of Biden’s popularity all but ensures Republicans will win back the US House of Representatives in the November 2022 midterms. With only a six-seat majority in the House of Representatives, everything needs to go right for Biden and his party in order to buck one of the empirical regularities of US politics: that the party of the president loses seats in Congress at the midterms. Figure 1.3 indicates that with Biden’s approval rating in the low 40s, keeping midterm seat losses to under six seats would be unprecedented. History shows this can be done, but only when a president is especially popular: examples of first-term presidents accomplishing this include President George W. Bush in 2002 after the September 11, 2001 attacks, President Kennedy in 1962 and President Eisenhower in 1954.

Figure 1.3. The political party of the president usually loses congressional seats in midterm elections, especially with low presidential approval ratings

Midterm seat losses in the House of Representatives for the party of the president, by the president’s pre-midterm election approval rating, 1946-2018. Democrats take a small, six-seat majority into the 2022 midterm elections.

Expectations Republicans will win control of the House in the November 2022 midterm elections have loomed large over the Biden presidency since it began and will continue to do so. With Democratic senators Manchin and Sinema all but certain to oppose most of the Biden legislative agenda, any appetite Democratic House moderates might have had for boldness has largely evaporated. Indeed, Democratic boldness might only come from the “swan song” votes of a record number of retiring Democrats. The balance of the 117th Congress is then likely to be consumed by ’position-taking,’ with legislators in safe seats shoring up their position in their parties’ primaries, and Democrats using their control of the congressional agenda to find votes that put Republicans representing moderate seats in politically awkward positions. Little substantive legislating can be expected to result.

This erosion of Biden’s popularity all but ensures Republicans will win back the US House of Representatives in the November 2022 midterms.

Hovering over all of these developments is former President Trump and the spectre of his leadership, or inspiration, of yet more democratic backsliding in the United States (see more below).

Remarkably, despite Republican losses in the 2018 midterms, the 2020 presidential election, and the 2020 Senate and House elections, Trump’s hold over the Republican party appears mostly undiminished. The “Big Lie” that the 2020 election was stolen from Trump has, correspondingly, become an article of faith for Republicans. Perhaps more remarkably, only the bravest or most secure Republicans dare critically examine the January 6, 2021 Capitol riot and its attempted subversion of the 2020 election result. One recent indication of Trump’s hold was the Republican National Committee censuring the Republicans participating in the congressional investigation into the Capitol riot, despite many Republicans condemning those events at the time.8

In turn, the “Big Lie” has become the rationale for an accelerated Republican-led campaign of legalised voter suppression across several US states, involving the consolidation of election administration powers in Republican-controlled state legislatures, and partisan gerrymandering.

Meticulous research by New York University’s Brennan Center for Justice finds that 2021 saw far and away the most state legislative activity aimed at restricting voting access in the 11 years since they have been tracking these statutes. Indeed, a third of all the restrictive voting laws seen since 2010 were passed in 2021. According to the Brennan Centre, in 2021:

at least 19 states9 passed 34 restrictive laws…[that]… make it more difficult for voters to cast mail ballots that count, make in-person voting more difficult by reducing polling place hours and locations, increase voter purges or the risk of faulty voter purges, and criminalize the ordinary, lawful behavior of election officials and other individuals involved in elections.10

The following analysis traces the form, extent and sources of democratic backsliding in recent years in the United States, drawing on original survey research and analysis by the United States Studies Centre. In turn, it documents historically high levels of isolationism, a profound lack of optimism about the future of the United States, and deep partisan disagreements about what problems the United States faces — at home and abroad — and how to address them.

Quite simply, the United States is less democratic than Australia, perhaps not by much in decades past, but unmistakably so now.

It is commonplace to identify “shared democratic values” as the rationale for Australia’s close relationship with the United States. But, the analysis presented here leads to a more confronting, harder truth. Quite simply, the United States is less democratic than Australia, perhaps not by much in decades past, but unmistakably so now. Moreover, the United States remains prone to democratic backsliding at best, if not a deep erosion of liberal democracy.

Australia can and should put our democratic values at the heart of strategic policy. But Australia may well face a future in which the gap between reality and rhetoric about the alliance cannot be ignored. An honest appraisal of Australia’s interests in its deep and broad relationship with the United States now would be vital insurance for a future in which many Australians might rightly look askance at a United States they simply do not recognise as a healthy, flourishing liberal democracy.

Democratic backsliding in America

by Professor Simon Jackman

Over the course of the Trump presidency, analysis and commentary on democratic backsliding and authoritarian resurgence grew from a trickle to a flood. Turkey, Hungary, Poland, Brazil and India were the initial focus of this analysis, where the election of autocratic, “strong man” political leaders presaged an erosion of liberal democracy.

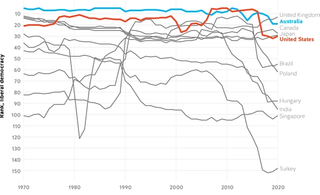

The United States joined this list of countries with diminishing levels of liberal democracy, as assessed by the internationally respected Varieties of Democracy (VDEM) project and shown in Figure 1.4.11 After falling to a global rank of 26th in 2001, the United States rebounded over the balance of the George W. Bush presidency, reaching a rank of fifth in 2007, the highest-ranking on liberal democracy ever obtained by the United States. The United States had fallen three places to eighth by the last year of the Obama presidency. But such a drop pales in comparison to the dramatic fall to 29th in the first year of the Trump presidency and a new low of 32nd in 2019.

Figure 1.4. The United States joins a list of countries where liberal democracy is in retreat

Varieties of Democracy Index, 1970-2020

Australia’s trajectory with respect to the VDEM liberal democracy index provides a vivid point of comparison. From Federation to 2006, Australia ranked as one of the world’s 10 highest-scoring countries on this metric. From 2016-2020, Australia’s median rank was 12th, compared to its 1901-2016 median rank of sixth. However, this fall is much less than that observed for the United States, which fell to a median rank of 30th since 2016.

In falling 25 places between 2014 and 2019, the United States joins a small set of countries in the 21st century to be or have been in the top 50 on this measure of liberal democracy and fall 25 places in a five-year span, thereby joining Poland, Hungary and Brazil.

Democratic backsliding, as assessed by expert ratings, measures democratic performance, typically, the actions of political elites, judiciary and the executive government of the day. Mass sentiment and support for democracy is a separate question.

USSC survey research reveals that despite the erosion of liberal democracy in the United States under the Trump presidency, ordinary Americans remain highly supportive of democracy as a system of government. On the other hand, evaluations about democratic performance are far more elastic, driven by partisan evaluations of incumbent leaders and parties.

In USSC surveys since 2019, survey respondents in both the United States and Australia were asked to evaluate the conduct and performance of democracy with the question:

On the whole, are you very satisfied, fairly satisfied, not very satisfied or not at all satisfied with the way democracy works in [America | Australia]?

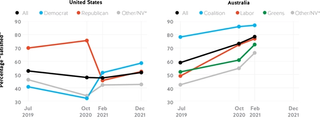

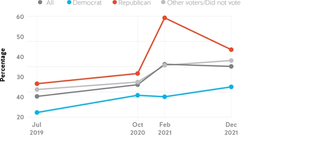

Over four separate surveys spanning July 2019 to December 2021, the US level of satisfaction with democracy hovers around 50 per cent (see Figure 1.5). Australians consistently report higher levels of satisfaction with democracy than Americans. Furthermore, Australians’ satisfaction with democracy across all partisan groups increased over the COVID-19 pandemic — from 60 per cent in July 2019 to almost 80 per cent in February 2021.

Figure 1.5. Americans are significantly less satisfied with democracy than Australians

Only half of Americans are satisfied with their democracy while four out of five Australians satisfied with theirs. Percentages reporting being “very” or “fairly” satisfied with democracy in their respective country, USSC surveys 2019, 2020 and 2021.

“Satisfaction with democracy” is strongly driven by partisanship. Supporters of the party in government report higher levels of satisfaction than partisans of the “out-party” in both countries. In the opening weeks of the Biden presidency, less than 50 per cent of Trump voters reported being satisfied with democracy in the United States, while Biden voters rebounded from 30 per cent before the 2020 election to more than 50 per cent after it and then 60 per cent in December 2021.

Asking respondents about their level of “satisfaction with how democracy is working” seems to elicit evaluations of the performance of the incumbent government more than a reflection on the performance of democratic institutions and procedures. It is seemingly akin to asking about presidential or prime ministerial approval. Note too, that in both countries and in each survey, respondents not voting or not supporting a major party or candidate consistently report lower levels of satisfaction with democracy — presumably both a cause and a consequence of being disinterested in politics and/or not supporting mainstream parties and candidates.

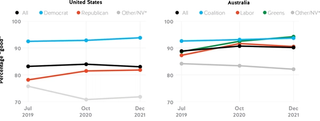

To better assess levels of support for democracy as a system of government we asked respondents if “having a democratic political system” was “very good, fairly good, fairly bad or very bad” for their respective country. Results from multiple USSC surveys are shown in Figure 1.6.

Figure 1.6. On average, US and Australian evaluations of democracy are similar, but this hides a concerning partisan divide in the United States

Percentages of respondents saying that a democratic system of government is either “very” or “fairly” good, by country and party, USSC surveys 2019, 2020 and 2021

Support for democracy as a political system is high and stable in the United States, with just above 80 per cent evaluating a democratic system of government as “very” or “fairly” good. Unlike evaluations of satisfaction with how democracy is working in the United States, partisan differences in evaluations of democracy as a system are smaller and more stable. Democratic voters are about 15 percentage points more likely than Republican voters to give a positive assessment of democracy as a system of government, irrespective of whether Trump or Biden is president.

Australians are slightly more supportive of democracy as a system of government than Americans, with a 90 per cent rate of positive assessments versus 83 per cent in the US data. There is no statistically significant variation between Coalition, Labor and Green supporters in evaluations of democracy as a system of government, with never more than five percentage points separating partisan groups (right panel, Figure 1.6).

The Australian data provides an important counterpoint to the situation in the United States. In the aggregate, support for democracy as a system of government sits just above 80 per cent in the United States. But like so much in contemporary US public opinion, it is concerning that views about such a fundamental tenet varies across parties in a stable and reliable way and by as much as 10 to 15 percentage points. Both well before the 2020 election and well after, two out of 10 Trump voters reported democracy as being “fairly” or “very” bad as a system of government. Anti-democratic sentiment reaching even this moderate level among the supporters of one of the major parties of the United States — the putative leader of the democratic world — is tremendously significant for democratic allies of the United States, given that shared democratic values figure so prominently in arguments for these alliances.

America’s illiberal turn?

by Professor Simon Jackman

Authoritarianism and populism are frequently invoked in describing what has been happening in American politics and society in recent years. But what are these phenomena? Why do they matter? And how can we measure their prevalence?

Authoritarianism manifests at both micro and macro levels: as a psychological attribute of individuals evidenced through measurements of relevant personality traits and attitudes; and as a property of a political system. At the micro-level, authoritarianism is constant and pervasive, with individuals more or less predisposed to authoritarianism in the same way that human beings differ with respect to other personality traits (like openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, etc). The more relevant question is how authoritarianism might become a feature of a nation’s politics, a question that has been studied almost continuously since the rise of totalitarianism in Europe ahead of the Second World War.12

The more relevant question is how authoritarianism might become a feature of a nation’s politics, a question that has been studied almost continuously since the rise of totalitarianism in Europe ahead of the Second World War.

Most accounts centre on whether political entrepreneurs are activating authoritarianism; in other words, building coalitions by appealing to individuals with authoritarian predispositions. This task may be easier if the polity is facing a threat or crisis where citizens are anxious and insecure and, as such, primed to receive authoritarian appeals. In addition, are political institutions porous, with low entry costs into the political marketplace, encouraging political entrepreneurs? Or does gate-keeping power and incumbency advantage vest in established political parties through electoral law and nominating procedures, in the media environment and in constitutional arrangements? Our assessment is that the US political system is far more porous than Westminster systems, or Canberra’s “Washminster” model.13

Populism is distinct from authoritarianism. It is a political ideology rather than a personality trait; rooted in the belief that political legitimacy derives from giving voice to “the will of the people” (or volonté générale, in Rousseau’s famous formulation). Central to populist narratives is opposition to an elite that purports to act in the national interest while corruptly enriching themselves, their patrons and clients (for example big business, intellectuals, foreigners, immigrants, racial and ethnic minorities).14 The elite at the centre of populist critiques is often portrayed as pervading mainstream political parties and other institutions like the media, rather than concentrated on any one side of a conventional left-right ideological continuum.

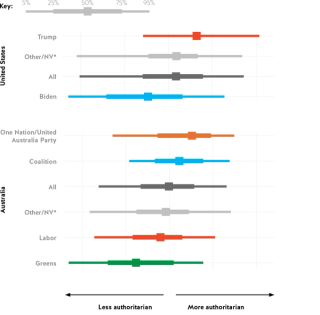

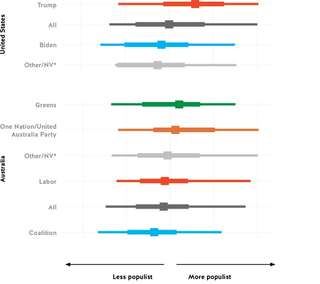

We investigated the prevalence and salience of authoritarianism and populism in US politics in our December 2021 survey. We measured authoritarianism with six items on characteristics deemed desirable in children, long-established as valid and reliable indicators of authoritarianism; and six items measuring components of authoritarianism, such as submission to authority, traditionalism and conventionalism.15 To measure populism we asked about attitudes toward political representation, perceptions of elites versus ordinary citizens, and willingness to compromise. These 18 items and a summary result for each country are shown in Table A2 of the appendix. Comparisons with Australian public opinion again provide a vivid counterpart.

We combine responses to the 12 items tapping authoritarianism and the six items tapping populism into two scales.16 Each scale is constructed such that zero is the mean score across both countries, with positive scores for respondents with more or populist attitudes and conversely for negative scores.

In short, authoritarianism tends to follow party affiliation across the political spectrum in both countries, but more strongly in the United States than in Australia. This is largely driven by the high levels of authoritarianism in Trump voters.

Overall, Americans score a little higher on authoritarianism than Australians, but these aggregate, cross-country differences are overwhelmed by the variation within each country (see Figures 1.7 and 1.8). As reported in appendix Table A3, the average difference between the United States and Australia is just 0.11 units, with the difference between Trump and Biden voters more than 10 times larger (1.18 units). Moreover, the probability that an American chosen at random has a higher level of authoritarianism than a randomly selected Australian is barely better than a coin flip, at 54 per cent; in contrast, a randomly chosen Trump voter has an 80 per cent chance of being more than a randomly chosen Biden voter.

Figure 1.7. Americans barely differ from Australians in levels of authoritarianism, but the US connection between political preference and authoritarianism is stronger

Distribution of authoritarianism by country and political support, formed by analysis of USSC surveys December 2021. In the US data, respondents are grouped by recalled vote in the 2020 presidential election; in the Australian data, by recalled 2019 House of Representatives vote. Details on scale construction appear in the methodological appendix.

Figure 1.8. Populism abounds in both countries, but Trump voters stand apart

Distribution of populism by country and political support, formed by analysis of USSC surveys December 2021. In the US data, respondents are grouped by recalled vote in the 2020 presidential election; in the Australian data, by recalled 2019 House of Representatives vote. Details on scale construction appear in the methodological appendix.

In Australia, only One Nation and United Australia Party voters come close to recording the same levels of authoritarianism typical of Trump voters. Trump voters are more authoritarian than Coalition voters by almost the difference between Coalition voters and Labor voters. In contrast, Labor voters appear slightly more authoritarian than Biden voters — and Green voters slightly less authoritarian — such that the distribution of authoritarianism over the combination of Labor and Green voters is extremely similar to that of Biden voters.

Every society has its authoritarians and it is not noteworthy that the United States has a significant proportion of its citizens exhibiting high levels of authoritarianism. So too does Australia. What is distinctive is that so many voters with authoritarian dispositions have parked their political loyalties with one of the United States’ major political parties, at least under Donald Trump. Conservative politics in Australia hasn’t been so captured, nor has it sought to capture the votes of authoritarians in the same way as the Republican party.

Trump voters also score high on populism (see Figure 1.8), with an average score of 0.56 standard deviations units above the overall mean score of zero; Biden voters have an average populism score of -0.17, with 0.73 standard deviation units separating the two voting blocs in the United States.

Overall, Australians display slightly lower levels of populism than Americans, but just as with authoritarianism, this cross-country variation is small relative to the within-country variation. Distinguishing between Americans and Australians in terms of the proportion of populists is barely more accurate than a coin flip: as reported in Table A4 in the appendix, the probability that an American chosen at random is more populist than an Australian chosen at random is just 54 per cent.17

However, comparing the concentration of populists among Trump voters contrasts starkly with what we observe in Australia. Between Coalition and Labor voters — supporters of Australia’s two parties of government — the difference in mean populism scores is just 0.29 units, or less than half the difference between Trump and Biden voters.

Populism in Australia concentrates among the supporters of smaller, non-governing parties: the Greens, One Nation and the United Australia Party. Supporters of the incumbent party of Australia’s national government, the Liberal-National Coalition, record the lowest average levels across both countries, so much so that populism does a very good job of distinguishing Coalition voters from Trump voters: the probability that a randomly chosen Trump voter is more populist than a randomly chosen Coalition voter is 75 per cent.

Some of the anti-establishment, populist sentiment reported by Trump voters is no doubt transitory, a reflection of the fact that Republicans have majorities neither in the House of Representatives nor the Senate and a Democrat is president. But these data also reveal a remarkable facet of contemporary US politics: that under Trump — and even after Trump was defeated in 2020 — the Republican Party’s supporters are disproportionately authoritarian and populist. Unlike Australian politics — where high levels of authoritarianism and populism are concentrated in the supporters of parties that do not form governments — authoritarianism and populism lie at the heart of mainstream US politics, shaping and structuring electoral competition and political discourse.

This illiberal turn in US politics has direct implications for Australian national interests, which we elaborate on in the following pages. Related to the currency, salience and concentration of authoritarianism and populism among Republican voters are historically high levels of isolationism, a profound lack of optimism about the future of the United States, and deep partisan disagreements as to what problems the country faces — at home and abroad — and how to address them.

The normalisation and mitigation of conspiracy

Long before QAnon or Pizzagate, conspiracy was enmeshed in American culture from its earliest days. Newly independent Americans were virulently anti-Masonic. The 19th-century Protestant majority was strongly anti-Catholic. After the Second World War, US senators and conspiracy theorists alike claimed godless Communists hid under beds and in the highest echelons of US institutions.18

The paranoid style of each movement is expressed through conspiracy theories. These theories most commonly hold that bad foreign actors are plotting to take down the United States and its experiment in democracy. Yet in addition to conspiracy, two newer catchwords have emerged in the age of social media, President Donald Trump and COVID-19: misinformation and disinformation. While often mistakenly used synonymously, these phenomena are distinct.

Misinformation “constitutes a claim that contradicts or distorts common understandings of verifiable facts.”19 By definition, misinformation is false. This falseness, however, is politically and ethically neutral; after all, ignorance and misunderstandings are normal features of our social lives. Claims hydroxychloroquine could treat COVID-19 were unsubstantiated, but like most misinformation about COVID treatments, were shared in an effort to try and help others.

Disinformation, on the other hand, is misinformation deployed to deliberately deceive and destabilise. When foreigners pretended to be Americans and ran online campaigns to shift votes in the 2016 election, they knowingly shared misinformation to achieve a certain outcome.

Conspiracy occupies shakier, less defined ground that, in turn, affects the foundations on which judgements are made about misinformation and disinformation. It is the assigning of intent in terms of a worldview that drives and spreads beliefs.

Conspiracy fuels both sides of US politics. The Russiagate assertions that Trump was a Manchurian candidate are as ridiculous or reasonable as claims that the 2020 election was stolen from Donald Trump. The dangers of partisan institutions touting conspiracy for political gain are evidenced by the January 6 Capitol riot.20

Complicating this challenge is the fact that traditional sources of knowledge and truth are fallible and fungible. Media outlets focus on topics, people and emphases that increase viewership; the US Supreme Court comprises partisan picks that set the parameters of US social and material life; rules and reasons around COVID-19 prevention change continually.

When this fungibility is combined with the intense affordances of online communication — where, for example, a very small number of often non-human accounts drive a disproportionate volume of misinformation21 — conspiracy becomes an almost necessary means by which to make sense of the world.

Merely dismissing citizens’ claims about the world as conspiracy has little positive effect because this kind of theorising is also undertaken by institutions and governments, which further destabilises the foundations on which any claims are made.

One increasingly bipartisan belief among members of Congress is that better regulation of speech on the internet could mitigate the dangers of misinformation, disinformation and conspiracy — most notably through amending Section 230 of the US Communications Decency Act. While this may constrain some extremes, conspiracy is ultimately an elemental feature of American life. Radical transparency in motive and action, as well as recognising the conspiratorial features of political communication, might be the only means by which institutional actors can responsibly navigate this challenging terrain.

America’s domestic policy priorities

by Professor Simon Jackman

Key issues for US allies are the US public’s appetite for bearing the costs of global leadership, the priority given to foreign policy and security challenges relative to domestic issues and, more broadly, America’s self-confidence and sense of purpose.

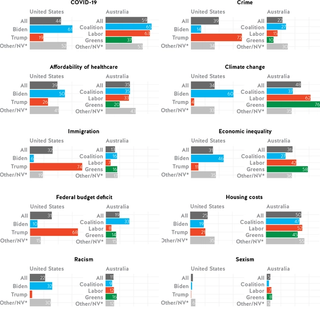

In USSC’s December 2021 survey, we asked Americans and Australians to choose their three most important issues from a list of 10. A summary of responses appears in Figure 1.9.

Figure 1.9. Americans can barely agree as to what are America’s most pressing problems, unlike Australia

Rates of listing a given policy issue as one of the country’s top-three problems, by country and party, United States and Australia, USSC surveys December 2021

COVID-19 is the primary concern, consistently selected as one of the United States’ top-three most important problems (MIPs), with 44 per cent of all respondents rating the pandemic in their top three. Thirty-nine per cent of Americans rate both crime and the affordability of healthcare among their top-three MIPs, followed by climate change (34 per cent) and immigration (32 per cent).

While COVID-19 is also the issue most frequently identified by Australians as a top-three issue (59 per cent), housing costs (50 per cent) and climate change (48 per cent), followed by economic inequality (36 per cent) and healthcare affordability (35 per cent), show a markedly different ordering of priorities than that seen for Americans. Crime is nominated as a top-three MIP by only 22 per cent of Australians, while just 25 per cent of Americans list the cost of housing as a top-three MIP. Twenty-two per cent of Americans nominate racism as a top-three MIP, but only 11 per cent of Australians.

We also observe considerable dispersion in the rates at which Americans select issues as MIPs. The top-three issues in the United States (COVID-19, crime and healthcare affordability) are nominated by 44 per cent, 39 per cent and 39 per cent of respondents. But the top-three MIPs selected by Australians (COVID, housing costs and climate) were selected by 59 per cent, 50 per cent and 48 per cent, indicating much more consensus in Australia about the country’s pressing issues than the United States.

Looking more closely at Figure 1.9, note the large cross-party differences in assessments of issue salience for the United States, with Biden voters’ MIPs being COVID-19 (61 per cent), climate change (60 per cent) and healthcare affordability (50 per cent), contrasted with Trump voters’ prioritisation of immigration (74 per cent), crime (72 per cent) and the budget deficit (68 per cent).

Table 1 further explores these cross-party differences in assessments of issue salience in both countries.

Table 1. Defining the country’s top problems: US and Australian political polarisation quantified

Differences across party lines on issue importance, by country. Table entries show percentages of each group of voters rating an issue as one of their top-three most important issues; |∆| is the magnitude of the difference of the ratings for each issue, between the two groups of voters in each country. Respondents are grouped by recalled vote in the 2020 US presidential election or the 2019 Australian House of Representatives election. The higher the |∆| number, the greater the magnitude of difference; the smaller the |∆| number, the more there is agreement between voters.

|

|

United States |

|

Australia |

||||

|

Issue |

Trump |

Biden |

|Δ| |

|

Coalition |

Labor |

|Δ| |

|

Immigration |

74 |

6 |

69 |

|

16 |

7 |

9 |

|

Crime |

72 |

14 |

58 |

|

27 |

15 |

12 |

|

Federal budget deficit |

68 |

10 |

58 |

|

33 |

8 |

25 |

|

Climate change |

4 |

60 |

56 |

|

37 |

62 |

25 |

|

COVID-19 |

19 |

61 |

41 |

|

65 |

63 |

2 |

|

Economic inequality |

11 |

46 |

36 |

|

27 |

42 |

15 |

|

Racism |

3 |

32 |

29 |

|

9 |

12 |

3 |

|

Affordability of healthcare |

26 |

50 |

24 |

|

35 |

33 |

1 |

|

Housing costs |

21 |

19 |

2 |

|

47 |

52 |

4 |

|

Sexism |

0 |

2 |

1 |

|

3 |

7 |

3 |

Take the case of COVID-19, the issue most frequently assessed as a top-three MIP in both countries. In the United States, 61 per cent of Biden voters rate this as a top-three MIP, but only 19 per cent of Trump voters agree. Contrast Australia, where 65 per cent of Coalition voters and an almost identical 63 per cent of Labor voters rate COVID-19 in their top three. Trump voters’ most frequently nominated issue, immigration (74 per cent), is ranked ninth out of 10 by Biden voters, with just six per cent of Biden voters placing immigration in their top three.

Americans are so polarised today that they disagree profoundly as to what are the nation’s most important problems, let alone what to do about those problems.

Climate change is rated as a top-three MIP by 61 per cent of Biden voters, making it the second-most salient issue for Biden voters; but only four per cent of Trump voters rate climate change a top-three MIP, ending up eighth out of the 10 for Trump voters. Climate change is one of the more polarising issues in Australian politics, but even in this case climate is the second-most salient issue for Labor voters (62 per cent rating it as top-three MIP) and the third-most salient for Coalition voters (37 per cent), the 25-point difference in salience ratings is the largest in the Australian data.

The high degree of cross-party consensus in issue salience in Australia is reassuring to a degree: supporters of Australia’s two major parties may disagree over policy, but there is, at least, consensus as to the challenges Australia faces. By contrast, the only things that Americans seem to agree on are that sexism is not an important problem and that housing costs are marginally important.

A bleak conclusion follows: Americans are so polarised today that they disagree profoundly as to what are the nation’s most important problems, let alone what to do about those problems.

America in the world

by Professor Simon Jackman

America’s foreign policy priorities

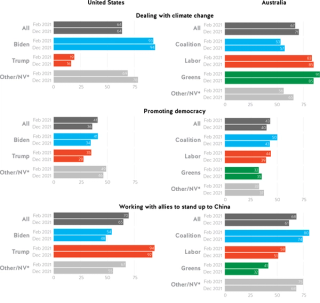

Repeating a question fielded in USSC’s February 2021 survey, we asked Americans to rate the importance of three different foreign policy priorities in our December 2021 survey. We asked Australians an identical question about Australian foreign policy priorities as well.

As shown in Figure 1.10, there is little change in the results between February and December 2021, save for a small increase in the importance accorded to “dealing with climate change” in the Australian data. Democracy promotion and “working with allies to stand up to China” fell in importance in both countries.

Figure 1.10. Polarisation in the United States extends to foreign policy priorities

Biden voters look similar to Australian Labor voters, but Trump voters stand apart from Coalition voters. Foreign policy priorities, by vote and country, USSC surveys February 2021 and December 2021. Respondents were asked to rate each foreign policy goal; the percentages plotted are the proportion of each group ranking the particular issue as their most important foreign policy goal or equally most important goal.

In aggregate, both climate change and the China-focused goal command the ‘highest importance’ assessments in both countries; climate change beats out “working with allies to stand up to China” in the Australian data, with 71 per cent giving climate change the top or equal top billing, versus 61 per cent for the China-focused item.22 In the United States, climate change and the “allies…China” goal are rated top or equal top by indistinguishable proportions, 64 per cent and 65 per cent, respectively.

The “Indo-Pacific” does not resonate for Americans

The “Indo-Pacific” is now firmly entrenched in the argot of strategic affairs, a successful case study in the way that the deft exercise of strategic imagination can give rise to strategic constructs and, in turn, changes in policy and facts “on-the-ground.” Unsurprisingly and unquestionably, the Indo-Pacific is the focus of Australian strategic policy. But how does the “Indo-Pacific” fare as a regional priority for ordinary Americans? In particular, from an Australian perspective, is it a helpful formulation to steer US strategic and public focus towards the region?

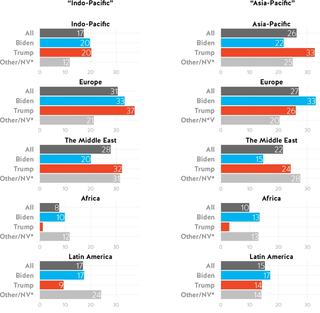

To assess this, USSC deployed a question-wording experiment, in which US survey respondents were asked “Which of the following regions should be the highest priority of the US Government?”

Five options were provided: Europe, the Middle East, Africa, Latin America and a random selection of either “Asia-Pacific” or “Indo-Pacific,” with the order of the five options also randomised. Responses are shown in Figure 1.11:

- Europe is the most popular choice for Americans irrespective of whether it is competing with “Asia-Pacific” or “Indo-Pacific.”

- The term “Indo-Pacific” appears to suffer from perhaps being unfamiliar to Americans, leading to a nine-point fall in the rate at which respondents nominate the region as their preferred “highest priority,” 17 per cent versus 26 per cent for “Asia Pacific.”

- While the “Asia-Pacific” (26 per cent) is virtually indistinguishable from Europe (27 per cent) and beats the Middle East (22 per cent) as a regional priority for the United States, the “Indo-Pacific” falls back to equal third with Latin America (17 per cent), far behind the Middle East on 28 per cent.

- Trump voters appear to be the most sensitive to the difference between “Indo-Pacific” and “Asia-Pacific.” “Asia-Pacific” is selected by 33 per cent of Trump voters, ahead of Europe (26 per cent) and the Middle East (24 per cent). Switching to the “Indo-Pacific” sees the region selected by only 20 per cent of Trump voters, far behind Europe (37 per cent) and the Middle East (32 per cent).

- Biden voters clearly see Europe as the most important regional focus for the United States, selected by 33 per cent (the same proportion of Trump voters that select “Asia-Pacific”), a position unchanged by whether Europe is competing with “Asia-Pacific” or “Indo-Pacific.”

Figure 1.11. Americans do not rate the Indo-Pacific as the priority region

Europe and the Middle East deemed more important while more preferred “Asia-Pacific” over “Indo-Pacific.” Respondents were asked to select one of five possible options in response to the question “Which of the following regions should be the highest priority of the US government?” Respondents were randomly allocated to one of two different versions of this question, one using the term “Indo-Pacific,” the other using “Asia-Pacific.” Results show the pattern of responses by the form of the question and by the 2020 presidential vote; USSC survey December 2021.

In the battle for hearts, minds and US strategic focus, words matter. Notwithstanding the success of embedding the “Indo-Pacific” in the world’s strategic vernacular, the term does not resonate with the US public, nor with Trump voters in particular.

On the contrary, the use of “Indo-Pacific” does nothing to draw the focus of Biden voters away from Europe; and drives Trump voters towards Europe, making Europe the single most popular choice of both Biden and Trump voters (33 per cent and 37 per cent, respectively).

Presumably, creating partisan consensus around Europe as the most important regional focus for the United States was not what thought leaders in the Australian strategic affairs community had in mind when popularising the term “Indo-Pacific.”

Presumably, creating partisan consensus around Europe as the most important regional focus for the United States was not what thought leaders in the Australian strategic affairs community had in mind when popularising the term “Indo-Pacific.”

Accordingly, it may be a case of carefully choosing the form of words being used when in dialogue with American counterparts: “Asia-Pacific” in public fora, and “Indo-Pacific” when in consultation with strategic affairs specialists.

Defence spending

Further, partisan disagreement is apparent when we turn to a critical policy variable: the size of the US defence budget. We asked survey respondents if the United States should “spend more” on defence, “spend less” or “maintain spending at current levels.” To assess the effect of different “frames” or “primes,” one version of the question references the current proportion of US Government spending directed towards defence; another version references the level of China’s defence spending relative to that of the United States; a “baseline” or “control” version of the item. Results are shown in Figure 1.12; the lower panel of the figure shows the difference between the “spend more” response and the “spend less” response, a measure of the strength of preference for increased or decreased defence spending.

Figure 1.12. Trump and Biden voters are almost diametrically opposed on defence spending, leaving no overall preference for increasing or decreasing defence spending

Quantifying US polarisation in defence spending shows little room for compromise. Respondents were asked if the US should “spend more”/“spend less” or “maintain spending at current levels” on defence, after being randomly assigned to one of three conditions: (1) a baseline/control condition with no additional text; (2) the question is preceded with the sentence “Currently, one out of every $10 spent by the US Government each year goes to defense” or (3) with a proceeding sentence which reads “Over the past 10 years, China’s annual defense spending has increased by 76 per cent to $250 billion. Over the same period, US annual defense spending has decreased by 10 per cent to $760 billion.” Responses grouped by 2020 presidential vote; USSC survey December 2021. The lower panel shows the difference between the percentages of those wanting more defence spending and those wanting less defence spending, by group. Positive/negative quantities imply a net preference for more/less defence spending within the group.

We see a familiar pattern in these data. Overall, there is very little appetite for increased defence spending, the result of strong preferences for decreased spending among Biden supporters, and, perhaps, slightly stronger preferences for increased defence spending among the slightly smaller group of Trump supporters. These differences across partisan lines are large and persistent and swamp the magnitude of any differences due to framing effects.

In aggregate, either of the two substantive priming conditions generates slightly more support for increased defence spending than the baseline, “vanilla” version of the question, where “spend more” trails “spend less” by seven percentage points. This margin drops to zero under the “China comparison” frame and is +3 in favour of “spend more” under the “US” frame.

The effects of the different frames or primes work inconsistently across partisan groups. Biden voters record their highest levels of “decrease” responses under the frame that reminds voters that defence accounts for about 10 per cent of US Government spending. Meanwhile, the “increase” response is seen least frequently among Trump voters under the frame that compares the United States and China, while this same frame seems to slightly tamp down Biden voters’ opposition to increased defence spending.

Partisan polarisation and the limits of American power

The most striking feature of these results is the large and persistent differences across party lines in the US data. Virtually every Biden voter in the survey rates “dealing with climate change” as the nation’s most important (or equally most important) foreign policy goal; less than one in five Trump voters are of the same view. Conversely, 92 per cent of Trump voters rate “working with allies to stand up to China” as their most important foreign policy goal, but just 48 per cent of Biden voters share this assessment.

There is more partisan agreement in the United States on the importance of allies standing up to China than on climate change as foreign policy priorities. But again, the contrast with the Australian data is revealing. Supporters of the conservative side of politics in both countries are more likely to prioritise standing up to China than climate change, while the converse holds for supporters of the centre-left parties. But even the largest partisan splits in Australia are small relative to those in the United States.

We assess that the Biden administration is probably slightly ahead of its supporters in its prioritisation of “working with allies to stand up to China” and defence spending, while probably lagging its supporters with respect to “dealing with climate change” as foreign policy goals.

Two conclusions follow. First, there is not a deep reservoir of political capital in the Democratic base for a tougher China policy; climate change animates the Democratic base much more than “working with allies to stand up to China.” Australian political leaders and policymakers ought to be sensitive to this fact: while there is a “policy establishment” consensus in Washington on the importance of China, this does not hold in the mass electorate. Perhaps ironically, the prospect of Republicans taking control of at least the House of Representatives over the second half of the Biden term will see fewer political headwinds in terms of defence spending and China policy from Congress, at the cost of deep deadlock on climate policy.

Isolationism

Any possible consensus on US foreign policy priorities must contend with other bleak data points revealed by our survey.

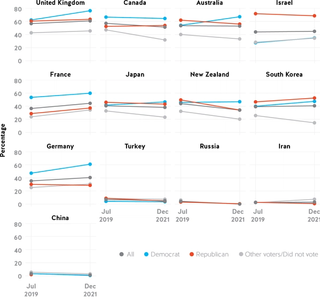

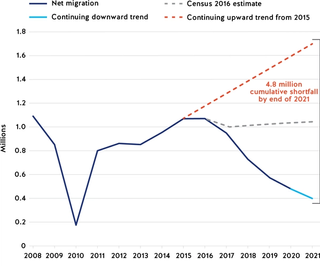

First, isolationism remains at historically high levels in the United States, with 40 per cent of Americans agreeing that “this country would be better off if we just stayed at home and didn’t concern ourselves with others’ problems” (see Figure 1.13). For decades, public opinion researchers used rates of agreement with this proposition as a measure of isolationism. Prior to 2016, the American National Election Studies never found more than 30 per cent of Americans to hold isolationist beliefs in a time series dating back to 1952, with levels of isolationism usually in the mid-20s.

Figure 1.13. US isolationism is at historically high levels, but remains a minority view

Percentages agreeing that “this country would be better off if we just stayed at home and didn’t concern ourselves with others’ problems,” by 2016 and 2020 presidential vote, USSC surveys July 2019 to December 2021.

It is also historically unusual for Republicans to be more isolationist than Democrats. But under Trump’s leadership, this long-standing regularity of US politics has been inverted. Well before Trump’s election loss in 2020, Trump supporters were already more than 10 percentage points more isolationist than Democrats. But note that all groups in the United States grew more isolationist between the July 2019 and October 2020 surveys. Immediately after Trump’s election loss in 2020, an unprecedented 60 per cent of Trump voters reported isolationist beliefs, moderating to about 45 per cent in USSC’s most recent December 2021 survey.

All political groups in the United States are growing more isolationist to levels seldom seen, if ever, in decades of public opinion research.

But at the same time — and with a Democrat as president — Biden voters have continued to trend in an isolationist direction, with more than 30 per cent reporting isolationist beliefs. The movement by Trump voters towards isolationism is a big part of the story. But all political groups in the United States are growing more isolationist to levels seldom seen, if ever, in decades of public opinion research.

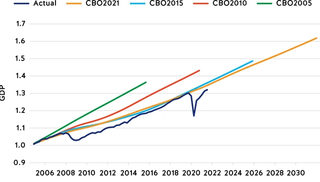

Pessimism about America’s future

Second, Americans have higher levels of pessimism about their country than we have seen in previous surveys. We measure this with a simple question asked on all of our surveys: “Are America’s best days in the future or have been in the past?” Figure 1.14 charts responses to this question over four USSC surveys, in both the United States and Australia.

Figure 1.14. Pessimism about the United States’ future is rising, even among Biden’s supporters

Percentages responding that America’s “best days are in the past,” by country and vote, USSC surveys 2019, 2020 and 2021

In USSC’s December 2021 survey, the proportion of Americans reporting that “America’s best days are in the past” rose to 60 per cent, comfortably more than a majority viewpoint, and an increase of about 15 percentage points, or a third, from July 2019. Again, this rise is not just a sour grapes response on the part of Trump voters, with 75 per cent of them giving the “best days in the past” response. Democrats have become more pessimistic even while they have a Democratic president, with almost 50 per cent providing the “in the past” response, their pessimism rising to levels they were reporting when Trump was president in USSC’s 2019 and 2020 surveys.

Optimism about the future of the United States is a minority viewpoint in Australia and across all voting groups, which largely tracks sentiment towards the United States more broadly. Coalition supporters are generally the least pessimistic about the future of the United States, followed by Labor and then the Greens. As has been the case in all our surveys, about 70 per cent of Australians say the United States’ best days “were in the past” — far more dour on prospects for the United States than Americans themselves.

Attitudes towards alliances and AUKUS

by Jared Mondschein and Professor Simon Jackman

Australia has had a formal security alliance with the United States since 1951. Australia has also fought alongside the United States in every major conflict since the Second World War. Little wonder then that Australia is consistently highly regarded as an ally within the United States. In the age of strategic competition, the US-Australia alliance is foremost among the US political and foreign policy establishment. But after enjoying preeminent status with a Trump administration not overly fond of most US alliances — and receiving one of the administration’s two State visits — has the perception of Australia been tarnished by US polarisation? How do ordinary Americans view the relationship between Australia and the United States?

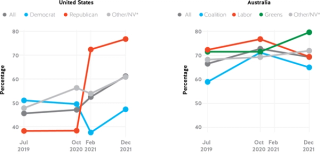

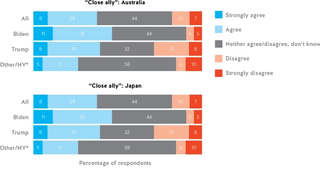

US respondents in both countries were asked to assess whether they saw other countries as an “ally” of their country, as “friendly” towards their country, as “unfriendly” towards their country, or as an “enemy” of their country (see Figure 1.15). About 53 per cent of Americans responded that Australia is an ally of the United States, a rate exceeded only by the United Kingdom (61 per cent). Australia outperformed other Indo-Pacific allies and partners on this measure, including Canada (51 per cent), New Zealand (34 per cent), Japan (28 per cent) and South Korea (41 per cent).

Figure 1.15. Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom remain the countries most often recognised as US allies

Percentage describing country as an ally of the United States, by 2016 and 2020 presidential vote, USSC surveys 2019, 2020 and 2021

Amid many differences between the Trump and Biden administrations, the role and view of US allies is one of the starkest contrasts. As much as the Trump administration prioritised ‘America First’ in their foreign policy, the Biden administration champions the role of allies, particularly in the age of strategic competition.

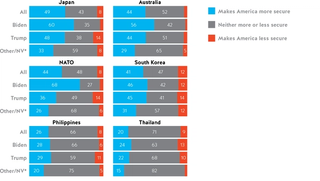

Given these different views as to the value of alliances between the Trump and Biden administrations, we asked US respondents whether six specific US alliances made the United States more secure, less secure or neither (see Figure 1.16).

Figure 1.16. Plurality of Americans are unsure if alliances make the country safer or not

"Do the following alliances make the United States more or less secure?” Responses grouped by 2020 presidential vote, USSC survey December 2021

Significantly more Americans said US alliances make the United States more secure than not — no more than 12 per cent of Americans said any of the six alliances made the United States less secure. Yet perhaps most striking is that, except for responses on Japan, the largest group of respondents — around half or more — said the US alliances made the United States neither more nor less secure. It seems that in most instances, the majority of Americans are unsure about the value of US alliances.

In September 2021, the Australian, US and UK governments announced the formation of the AUKUS trilateral security partnership. In addition to collaborating on deeper integration of security and defence-related science, technology, industry and supply chains, the longstanding allies pledged to support the Royal Australian Navy’s acquisition of nuclear-powered submarines.

Without mentioning that the AUKUS agreement had already been announced, USSC asked US respondents whether they agreed or not that the United States should share “technology used in nuclear-powered submarines” with close allies such as Australia and Japan (see Figure 1.17).

Figure 1.17. What’s AUKUS? Slightly more Americans support sharing nuclear-powered submarine technology with Australia than Japan

“The United States should share military technologies with a close ally, such as [Australia/Japan], including the technology used in nuclear-powered submarines.” Responses grouped by 2020 presidential vote; USSC survey December 2021. Respondents were randomly assigned to either the ‘Australia’ or ‘Japan’ version of the question.

Similar to respondent views on whether specific allies made the United States more secure or not, the plurality of US respondents appeared unsure on this issue. Slightly more Americans supported sharing the technology with Australia (35 per cent) than with Japan (31 per cent) but again, the largest group in both countries either did not know or were unsure.

2024 presidential candidates: US and Australian preferences compared

by Dr Shaun Ratcliff and Sarah Hamilton

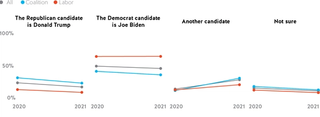

One year after the 2020 presidential election, Democratic presidential candidates maintain a small advantage in public support with both American and Australian audiences.

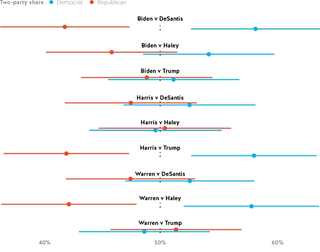

USSC tested presidential vote intentions by providing US respondents with three head-to-head electoral contests that randomly paired one of three potential Republicans versus one of three potential Democratic candidates for the 2024 presidential election. Despite the steadily declining approval rating of Democratic President Joe Biden — now lower at this point in his first term than any other modern president, except Donald Trump — most respondents still preferred the Democratic candidate, regardless of which Republican they faced. However, in most scenarios the margin was small.

Overall, there is little partisan movement from the November 2020 presidential election. Ninety-nine per cent of respondents who voted for Donald Trump at the 2020 presidential election said they intend to vote Republican in 2024, even if Florida Governor Ron DeSantis or former UN Ambassador Nikki Haley replaced Donald Trump as the candidate. Similarly, almost all (97 per cent) of those who voted for Biden in November 2020 still planned to vote for a Democrat in 2024, even if the head of the ticket was replaced with Kamala Harris or Elizabeth Warren.

Trump remains the preferred candidate for the 2024 presidential election for 95 per cent of Republicans. While the House Select Committee on the January 6 attack continues to close in on Trump’s inner circle, he still appears to be the Republican favourite for 2024. In general, voter sentiment about the Republican Party, and the former president himself, has recovered from prior lows.

Despite President Biden’s falling approval rating and Trump’s post-election sentiment recovery, more American voters still prefer a Democratic presidential candidate, regardless of which Republican they faced.

Our 2024 voting tournament

It is far from certain that either Biden or Trump will be their party’s candidate in 2024, or who may take their place as the top candidate for either party. Therefore, we tested the electoral strength of multiple potential candidates, three Democrats and three Republicans. Each respondent was presented with three random pairings from the set of nine possible Democratic/Republican match-ups, subject to the constraint that each respondent sees all three Democrats and all three Republicans in the match-ups presented to them. The following candidates were selected because they are recognisable to many Americans and are significant representatives of their respective parties:

Potential Republican candidates

- Former president Donald Trump

- Former US Ambassador to the United Nations and Governor of South Carolina Nikki Haley

- Current Governor of Florida Ron DeSantis

Potential Democratic candidates

- President Joe Biden

- Vice President Kamala Harris

- Senator for Massachusetts Elizabeth Warren

Respondents were asked, “If an election for president were being held today, and the following candidates were on the ballot, how would you vote?” A respondent received each candidate once, meaning they received all six over the course of three questions. However, the pairings were random.

The sample size of the two-party vote for these head-to-head match-ups was small (approximately 300). With a sample size of 1,200, and three match-ups presented to each respondent, each of the nine match-ups is shown to about 400 respondents, but each Democratic and each Republican candidate appears in 1,200 match-ups. This design sees us trade-off precision with respect to any particular match-up against unduly burdening our survey respondents, while at the same time giving us considerable statistical power with respect to the electoral strength of each candidate. The respondents were drawn from a representative sample of the United States, rather than filtering only for likely voters. Because voting is not compulsory, sentiment and candidate preference may not translate into actual votes and a significant factor in 2024 will be how well the candidates can draw voters to the polls.

Despite the apparent preference for Democratic candidates, in most scenarios the margin was small. In seven of the nine possible scenarios, the Democratic candidate was estimated to win the two-party popular vote (Figure 1.18). The exceptions to this were Elizabeth Warren versus Donald Trump, and Kamala Harris against Nikki Haley. In both cases, the Republican candidate’s lead was not statistically significant, suggesting caution in inferring too much from these results. In most scenarios, the Democratic lead was also often small and within the margin of error.

Figure 1.18. Nine hypothetical presidential match-ups

Estimated two-party vote with different candidates

However, in four instances the Democratic lead was larger. Three were exceptionally large: Biden versus DeSantis, Harris versus Trump and Warren versus Haley (all with margins of approximately 16 per cent). Biden versus Haley was also large (with an eight per cent gap) and outside the margin of error.

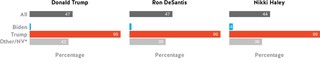

The preference results for Republican candidates are shown in Figure 1.19 and Democrats in Figure 1.20. These include estimated support across the entire sample (the grey bar in each plot) and by vote at the 2020 presidential election. Averaged over the nine match-ups, we find Trump to be unambiguously the best performing Republican candidate, followed by DeSantis and a substantial gap to Haley. Biden and Harris perform equally well over the pairings against the three Republican candidates, well ahead of Warren.

Figure 1.19. Biden still beats out Kamala Harris and Elizabeth Warren for the Democratic vote

Voter intention by 2020 vote if the 2024 Democratic candidate is...

Figure 1.20. Donald Trump and Ron DeSantis top Republican preferences

Voter intention by 2020 vote if the 2024 Republican candidate is...