Executive summary

- A change in the sources of foreign direct investment (FDI) in Australia and the United States has raised concerns about national security risks that may arise from such investments.

- Both Australia and the United States have mechanisms to screen FDI and retain statutory powers to block, or order the divestment of, foreign acquisitions. These processes are currently being revised to better protect national security.

- The issue for policymakers is how to maximise the benefits of foreign investment, while addressing legitimate national security concerns.

- Whereas Australia’s regime is built around an open-ended ‘national interest’ test, the US process is explicitly directed at investment that ‘threatens to impair the national security of the United States’.

- The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) provides a useful model for how Australia could reform its foreign investment screening process to better focus on national security issues, while leaving other non-security policy issues to domestic regulatory frameworks behind the border.

- Australia’s process has been more focused on protectionism and has struggled to integrate national security considerations in a systemic way, resulting in confused policymaking and uncertainty for foreign investors.

Policy recommendations

- The government’s discretion to reject foreign investment applications should be exercised only in relation to national security issues or cases where domestic regulatory frameworks are unable to address policy issues raised.

- Australia’s Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB) should be overhauled to better integrate consideration of national security and critical infrastructure issues. FIRB should report to the National Security Committee (NSC) of federal cabinet rather than the treasurer on national security issues. The NSC should be the decision-making authority rather than the treasurer.

- The Australian government should develop broad principles for assessing national security risks and make these principles publicly available. The principles should be suitable for multilateral adoption in free trade agreements and investment treaties. The process for applying these principles should be articulated in a publicly-available government guidance document.

- Critical infrastructure and other assets deemed too sensitive to allow foreign ownership should be identified either through statutory restrictions on foreign ownership or a negative list to increase certainty for foreign investors.

- FIRB should improve its reporting to parliament, including through confidential hearings to parliamentary committees to protect classified and commercially sensitive information.

- There is a lack of coordination between Australia and the United States in evaluating and addressing national security risks that may arise from foreign investment. A memorandum of understanding should be signed between the Australian and US governments for the exchange of information and setting out procedures for consultation and the joint consideration of cross-border acquisitions that raise common national security issues. This would complement existing ‘Five Eyes’ processes in relation to intelligence sharing.

Introduction

Both the United States and Australia rely on foreign direct investment (FDI) as a major source of capital to fund domestic investment and economic growth. FDI has long been recognised as an important driver of productivity growth. FDI, usually defined as foreign ownership of 10 per cent or more of a company, commonly involves the transfer of technology, management techniques, intellectual property, and other forms of intangible capital. These knowledge transfers typically enhance productivity in the local operations of foreign-owned enterprises, but also generate spillover benefits for productivity in the rest of the economy. FDI is typically more long-term and more stable than other forms of capital inflow, like portfolio investment, usually defined as ownership of less than 10 per cent of a company. FDI gives foreign investors a long-term stake in the economy.

Cross-border acquisitions of domestic businesses and assets by foreign firms can be controversial and raise a number of potential issues for policymakers. One of the more difficult issues facing policymakers is how to trade-off the mostly well-understood benefits of FDI against potential threats to national security from foreign acquisitions.

The prominent role of state-owned enterprises in outbound foreign direct investment from economies such as China raises concerns that such investments may have strategic rather than purely commercial motives.

While most foreign acquisitions do not raise national security concerns, security considerations have become more salient in recent years due to a change in the sources of FDI. Traditionally, most foreign investment in the United States and Australia was sourced from other developed Western market economies that also enjoyed close security ties through formal alliance relationships. In this context, FDI rarely raised national security concerns.

The rise of emerging market economies as net savers and exporters of capital in the world economy has seen the sources of inward FDI shift to countries such as China that have a more problematic strategic and security relationship with the United States and Australia. The prominent role of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in outbound FDI from economies such as China raises concerns that such investments may have strategic rather than purely commercial motives. In Australia, an estimated 83 per cent of Chinese acquisitions by number and 60 per cent by value were from private investors in 2017.1 In the case of the United States, 90 per cent of inward FDI still comes from private investors.2 At the same time, however, the proportion of companies having 50 per cent or more government ownership among the Fortune Global 500 grew from 9.8 per cent in 2005 to 22.8 per cent in 2014.3 In any event, even private firms can be responsive to demands from their governments. Intellectual property, technology, data and knowledge transfers have become more important as drivers of FDI and this may have security implications where these technologies or data have military applications or threaten to diffuse technology leadership from the United States and Australia to strategic rivals such as China.

China has increasingly resisted convergence with international market economy norms in favour of its ‘Made in China 2025’ state-led development model that aspires to global leadership in key industries and technologies with both civil and military applications. An important element of this mercantilist development and innovation strategy is the appropriation of knowledge and technologies through both inward and outward FDI. This industrial strategy is closely tied to China’s strategic and military objectives and has been given added impetus through the consolidation of domestic political power under President Xi Jinping since 2012. These developments call for a re-evaluation and re-calibration of frameworks for the regulation of FDI to focus more squarely on national security issues at the border, but also more rigorous governance and security arrangements for sensitive assets and critical infrastructure behind the border.

Australia and the United States are not the only countries seeking to address the national security issues raised by foreign investment. The United Kingdom, which has traditionally maintained an open-door policy with respect to FDI, has sought to introduce increased screening at the border. Other EU countries have also sought to implement increased scrutiny of foreign acquisitions on a national and EU-wide basis.4

This report outlines some of the national security issues raised by recent changes in the sources of FDI in Australia and the United States. The regulatory regimes for screening FDI in both countries are examined, with a particular focus on how these regimes handle national security issues. The policy recommendations are focused on how Australia can improve its regulatory regime for FDI to better focus on national security issues, using the United States as a model for reform. The aim of the report is not to prescribe the detailed content of Australia’s foreign investment policy. It is to articulate in general terms a better approach that elevates national security concerns to the centre of the FDI screening process by redefining the national interest test in terms of national security issues, while turning other issues over to domestic regulatory processes.

This can be done within the framework of current legislation, although would require a substantial re-writing of the government’s existing foreign investment policy.

Why reform is needed

Both Australia and the United States have processes in place to screen FDI and retain statutory powers to block, or order the divestment of, foreign acquisitions. In Australia, this process is based on advice from the Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB). In the United States, the process is administered by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS). Appendix 1 compares the FDI screening and approval processes in both countries. The most important difference between them is that whereas Australia’s regime is built around an open-ended ‘national interest’ test, the US process is explicitly directed at investment that ‘threatens to impair the national security of the United States’.5

The processes in both Australia and the United States are not as well-defined as they could be and have struggled to respond in a coherent and predictable way to some of the potential national security issues raised by recent foreign acquisitions. According to the Peterson Institute for International Economics, a US think-tank, “the CFIUS process…remain[s] opaque and grant[s] excessive discretion to the executive branch”.6 Similar criticisms have been made of Australia’s FIRB.7 This lack of transparency and excessive discretion has created uncertainty for foreign investors and may have a deterrent effect on FDI.

The processes in place to screen FDI in both Australia and the United States are not as well-defined as they could be and have struggled to respond in a coherent and predictable way to some of the potential national security issues raised by recent foreign acquisitions.

The challenge for policymakers is how to maximise the benefits of foreign investment, while addressing legitimate national security concerns. This requires a deeper understanding of how foreign ownership might affect national security, defence capabilities and critical infrastructure in both theory and practice. This understanding should then inform the institutions and processes put in place to screen FDI at the border and to regulate business investment behind the border. Without this understanding, acquisitions with substantial economic benefits may be blocked or deterred based on apprehended security concerns that are not well-founded. In the absence of this understanding and the implementation of sound review mechanisms, there is also an increased danger that the foreign investment review process becomes ad hoc and/or politicised.

Security concerns run in both directions between a source and host country. Foreign investors want to ensure that the value of their assets will be protected and not subject to arbitrary expropriation or divestment. To protect their assets, foreign investors, including foreign governments, have strong incentives to adhere to domestic law and avoid provoking retaliation by host country governments. The accumulated stock of inward FDI gives the host country leverage over foreign investors, including foreign governments. In the extreme case of armed conflict, FDI can be subject to expropriation by the host country government, inflicting economic and strategic harm on the source country. Indeed, the risks to the source country in this scenario are likely to be larger than to the host country to the extent that it has the larger stock of FDI at risk.

It is an open question as to whether economic integration through increased cross-border trade and investment reduces the likelihood of international conflict. The world was highly economically integrated before the First World War, but this did not prevent the outbreak of conflict. While there is a growing view that China has failed to converge on the international norms favoured by the United States and Australia, the underlying economic and political case for drawing China into the world economy remains valid. The regulation of foreign investment into Australia and the United States should be integrated with broader diplomatic and security strategies aimed at disciplining the behaviour of countries like China.

Indiscriminately pushing back against Chinese FDI could also be counter-productive and actually encourage China to double-down on its own protectionist actions and indigenous innovation strategy. If Chinese capital stays at home, it is more likely to be used to finance indigenous innovation at the expense of innovation in Australia, the United States and other allied economies. Failing to capitalise on Chinese investment may hinder domestic economic development, to the detriment of national security. The size of the economy is an important foundation for national security. The military, diplomatic, foreign aid and other capabilities Australia brings to its international and security commitments are ultimately constrained by the fiscal resources available to government, which in turn depend on the size of the tax base. This suggests a delicate balance between rejecting transactions that may pose specific national security risks while seeking to capitalise on the benefits of Chinese investment abroad.

Foreign direct investment and national security

There are a number of ways in which foreign acquisitions of domestic businesses and assets may give rise to national security concerns. Until recently, these concerns have been more apprehended than real. Rosen and Hanemann, experts on Chinese investment in the United States, made the following observation in 2011 before China’s recent authoritarian turn:

We find the open-source literature on the security risks associated with Chinese firms to be full of overgeneralisations, mischaracterisations and weak evidence — oftentimes consisting in large part newspaper citations of work by journalists that do not carry sufficient evidentiary weight… We are aware of no damage to US national security that can be attributed to a faulty approval process.8

This conclusion was also drawn in relation to foreign portfolio investment by sovereign wealth funds. According to David Marchick and Matthew Slaughter, “no one has pointed to a [sovereign wealth fund] investment that compromised national security in any country in the last five decades”.9

More recently, attitudes towards China have hardened in both Washington and Canberra. There are now good reasons to be less sanguine about foreign investment from countries like China. China’s increasingly assertive international economic and security policies make it prudent to consider the worst case scenarios arising from prospective foreign acquisitions. Probabilities can then be assigned to these scenarios and weighed against the economic benefits of a given transaction to make judgements about the appropriate policy response. Even if national security considerations are rarely invoked as a result of the FDI screening process, they are sufficiently important to require a well-developed and well-articulated process for analysing and addressing them. Even a single transaction could potentially undermine national security if not well handled.

Theodore Moran, a leading expert on the regulation of foreign investment, suggests a typology of national security threats that might arise in the context of FDI.10 These are:

- Threats to reliability of supply to the defence sector or broader economy of critical goods and services.

- Threats arising from technology or data transfer to foreign interests.

- Threats arising from an increased potential for infiltration, surveillance or sabotage.

While it is easy to identify potential threats in principle, it is much more difficult to establish that there is an actual threat in practice from a particular foreign acquisition. A transaction that might be viewed as benign today may become less so in the future as strategic circumstances change. FDI screening processes cannot anticipate all future contingencies. The burden of protecting national security needs to be met behind the border over time, rather than at the border at a particular point in time. The case studies discussed in Appendix 2 demonstrate that, historically at least, some of the transactions that have raised national security concerns did not constitute genuine security risks or these risks were successfully mitigated. It is nonetheless useful to establish benchmarks or thresholds for thinking about how each of these threats might trigger formal review processes and decisions to reject particular transactions.

Reliability of supply

Competitive and open domestic and international markets provide the best security against possible attempts to restrict supply in ways that might be harmful to national security as well as to the economy. Most markets for key industrial and agricultural commodities are supplied in this context, making it unlikely that a foreign acquisition could pose a significant threat to security of supply. This is particularly the case for the United States and Australia, both of which are net producers and exporters of some commodities. For example, the issue of food security has been raised in the context of foreign acquisitions of Australian agribusiness and agricultural land, but as a significant net producer and exporter of food, it is implausible that Australia could suffer from meaningful threats to food security through foreign acquisitions of Australian land or agribusiness.

Domestic competition policy addresses issues where mergers and acquisitions might reduce competition or supply in ways that are economically harmful and these regulatory frameworks can be applied without screening acquisitions at the border.

Energy security has raised similar concerns, although these have become less salient for the United States and Australia given that both economies are increasingly significant exporters of energy, particularly natural gas. China’s investments in oil and gas have sometimes raised concerns, but in the case of Chinese investment in oil production, almost all output is sold into world markets rather than being allocated specifically to the Chinese market.11 Most commodity markets are sufficiently fungible that there is no advantage to selling into a specific, as opposed to world markets, although China and the United States have recently discussed LNG purchases as a means of addressing trade imbalances. Rare earths have also been the subject of Australia’s FDI screening process on the basis of security of supply concerns, as discussed in one of the case studies in Appendix 2.

In principle, situations may arise where there is a single or small number of producers of a key technology or input, with few substitutes and high switching costs, which may give rise to security concerns, but this does not appear to be common in practice. Domestic competition policy addresses issues where mergers and acquisitions might reduce competition or supply in ways that are economically harmful and these regulatory frameworks can be applied without screening acquisitions at the border. If such acquisitions are not harmful from a competition policy perspective, it is unlikely they also pose a threat to the reliability of supply from a national security standpoint. Competition policy and strategic trade theory, which analyse the economics of markets that are imperfectly competitive, provide useful benchmarks for when a cross-border acquisition might threaten undue concentration or the reliability of supply. However, a notable characteristic of the literature in these fields is that these tend to be special cases that arise in theory more so than in practice.12

Technology, information and data security

There is a case for restricting foreign acquisitions involving sensitive military or dual-use technologies. Since technology and knowledge transfer are often important motivations for FDI, this concern is significant in principle. Typically, technology and knowledge transfers are a feature of outward FDI, with the benefits accruing to the host country and so this is less of a concern for the inward FDI screening process. However, technology and knowledge transfer can also run from host to source country.

Concern over China’s systematic, state-sponsored theft of foreign technology is legitimate, but increased restrictions on foreign investment may not be the right way to tackle the problem.

China’s use of joint venture arrangements to affect forced technology transfers from foreign firms in violation of the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) Trade and Investment Measures and its own WTO Accession Protocol has become an important issue for the United States and a source of friction in the overall trade and investment relationship between the two economies. Recent research has shown that these often forced technology transfers have significant positive productivity and technology spillovers for the Chinese economy via US investment in China.13 Chinese firms harvesting US technology through investments in start-ups and other entities that fly below the radar of the existing FDI screening process have become a key concern.14

Concern over China’s systematic, state-sponsored theft of foreign technology is legitimate, but increased restrictions on foreign investment may not be the right way to tackle the problem. There are alternative, more targeted policy instruments that can be used.

Both the United States and Australia maintain export control and technology transfer regimes that are better tailored to address the issue of technology transfer from host to source country and these regimes are in the process of being enhanced. China’s forced transfers of intellectual property through joint venture and other arrangements can and should be challenged through the WTO or through targeted sanctions on offending Chinese firms.

Data and information security has become increasingly important and potentially raises national security issues that have already led to a failure to approve foreign acquisitions in the United States (see, for example, the Ant Financial-MoneyGram transaction discussed in Appendix 2).

Technology transfer and data security risks can potentially be mitigated without rejecting acquisitions in their entirety. Key technologies and intellectual property can be carved out of foreign acquisitions as part of the FDI screening process or addressed through appropriate governance arrangements.

Ideas want to be free and new technologies will eventually diffuse across international borders. That is mostly for the better. It is unrealistic to expect that the world’s soon-to-be-largest economy will forever remain a technology laggard. However, the fact that China relies heavily on appropriating foreign technology is itself evidence that it is struggling to compete in fostering institutions and a culture conducive to innovation and progress. The history of state-directed economic development strategies such as ‘Made in China 2025’ is littered with costly failures. Japan in previous decades is an obvious example that also gave rise to security concerns about foreign investment similar to those now raised about China.

The main advantage the United States and Australia have over China is not specific innovations that will be appropriated by foreigners, either legally or illegally, but the institutional framework that sustains their creation. That framework includes open capital markets, the rule of law and intellectual, political and cultural freedom.

Infiltration, surveillance and sabotage

Foreign acquisitions of critical infrastructure or even acquisitions co-located with such infrastructure could give rise to opportunities for infiltration, surveillance and sabotage that might not otherwise be available to a foreign power. Yet such covert and overt threats exist even in the absence of foreign ownership, and foreign ownership would seem to be an inefficient and costly way of acquiring these capabilities. By comparison, Chinese and Russian government-sponsored hacking and cyber warfare represent more significant security risks, but do not depend on FDI or even a physical presence in the target country for their effectiveness and can be implemented at very low cost.

The threshold question that needs to be addressed in these cases is the potential for these threats to materialise as a direct consequence of foreign ownership. In many cases, these threats will exist independently of ownership.

The threshold question that needs to be addressed in these cases is the potential for these threats to materialise as a direct consequence of foreign ownership. In many cases, these threats will exist independently of ownership. A careless or poorly governed domestic owner of a critical asset that did not pay attention to security risks could provide opportunities for a foreign power to exploit vulnerabilities without ever making an appearance on the share register of the operating business.

These threats are better addressed by applying security screening to the employees and managers of the entity owning and operating sensitive assets, regardless of whether the entity is foreign-owned or not. Such screening should apply even when the asset is in domestic ownership and control given that security risks can be sourced domestically as well as internationally. Employees of domestically-owned firms can be bribed, blackmailed and otherwise coerced into providing information to foreign intelligence services or sabotaging domestic assets. Ideologically or politically-motivated domestic actors may threaten these assets even without direction from foreign governments. It is the role of domestic intelligence and law enforcement agencies to combat these threats. Resources devoted to screening FDI at the border may be more effectively devoted to domestic counter-intelligence efforts to combat real threats as opposed to apprehended threats that may never materialise.

These potential threats argue either for statutory restrictions on foreign ownership or the creation of lists of critical assets and infrastructure for which ownership might be regulated and subject to special conditions. These obligations should apply equally to domestic or foreign owners given that these threats are often independent of ownership. In the case of extremely sensitive assets, it might be thought desirable to maintain the assets in domestic and even public ownership. It is the nature and quality of the governance of these assets that needs the most scrutiny. While ownership is part of the governance structure, the composition of the share register of the operating entity may not be a good guide to security risks. A change in a foreign ownership stake from five per cent to 20 per cent might trigger the FDI screening process, but in itself does not seem very informative about national security risks.

Australia’s regulatory regime for FDI

Australia’s regulation of FDI at the border is built around the concept of ensuring that foreign investment is not inconsistent with the ‘national interest’. A negative test is applied to foreign acquisitions that fall within the scope of the screening process. The ‘national interest’ is deliberately left undefined in the Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Act 1975,15 mainly with a view to putting ministerial determinations in relation to foreign acquisitions outside the scope of judicial review. The government does maintain a foreign investment policy designed to give guidance to foreign investors on how the national interest test might be applied in various contexts, although this guidance is indicative only and non-binding on the treasurer as the final decision-maker under the Act.

Successive governments have interpreted the ‘national interest’ test as incorporating national security considerations, but the concept is a much broader one, taking in competition policy issues, tax considerations, economic and community impacts and the character of foreign investors. The test is much broader in scope than that applied in the United States and applies to a wider range of assets. The screening thresholds vary based on whether Australia has a free trade agreement with the source country and whether the foreign investor is privately or publicly-owned (see Appendix 1).

By both value and number of acquisitions, Australia had more cross-border inward and outward merger and acquisition transactions fail for regulatory or political reasons than any other jurisdiction between 2008 and 2012.

The national interest test affords the treasurer a broad discretion to reject foreign acquisitions based on a range of criteria with little effective judicial or administrative oversight. This discretion is valuable to politicians, giving them the flexibility to respond to controversial cross-border acquisitions in a way that is politically optimal for them. However, it is a sub-optimal regime from the perspective of investors because of the costly risk, uncertainty and delays the FDI screening process creates, even when transactions are ultimately approved. The treasurer’s discretion serves as a lightning rod for special interests, which politicises cross-border transactions caught within the screening framework.

The Shell-Woodside, Chinalco-Rio, SGX-ASX, ADM-Graincorp proposed acquisitions are all examples of major transactions that became politicised and ultimately failed as originally proposed due to the FDI screening process.16 The Australian government’s consideration of Chinalco’s proposal to increase its stake in Rio Tinto in February 2008, which was referred to the National Security Committee of federal cabinet by the Rudd government, was widely criticised, highlighting weaknesses in both process and policy.17 According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, by both value and number of acquisitions, Australia had more cross-border inward and outward merger and acquisition transactions fail for regulatory or political reasons than any other jurisdiction between 2008 and 2012.18 Australia ranked second only to China in one recent global survey of countries where significant rule of law risks occurred in relation to foreign investment.19

National security is explicitly invoked as a criterion for the national interest test in the government’s foreign investment policy. The policy states that:

The Government considers the extent to which investments affect Australia’s ability to protect its strategic and security interests. The Government relies on advice from the relevant national security agencies for assessments as to whether an investment raises national security issues.20

The policy also identifies sensitive sectors that are subject to more rigorous screening, including “defence related industries and activities and the extraction of uranium or plutonium or the operation of nuclear facilities as well as other critical infrastructure”. Otherwise, the statutory and non-statutory policy framework gives foreign investors little guidance on how the national interest test might be applied to prospective acquisitions. This creates uncertainty for foreign investors and has generated diplomatic and commercial frictions when the framework has been applied in ways that were not anticipated by foreign governments or investors.

Foreign government investors are subject to automatic scrutiny in situations where private investors are not. However, foreign government ownership may not be a good guide to whether an acquiring firm poses national security risks. A privately-owned foreign company might still be responsive to demands from its home government or be compromised in other ways. For example, concerns have been raised over the privately-owned Chinese telecommunications company Huawei and the links of its founder to China’s People’s Liberation Army. China’s government mandates cooperation with the state and its security services through its national security laws. These concerns resulted in Huawei’s exclusion by the Australian government from supplying equipment to Australia’s National Broadband Network.21 Huawei may also be precluded from participating in the development of Australia’s 5G network. It is worth noting that an extensive US government security review of Huawei failed to find evidence of Huawei facilitating Chinese espionage.22 A widely-cited US congressional report identifying Huawei as a security risk was also criticised for its lack of substance.23 However, both the Australian and US governments remain concerned about security risks from Huawei.

There are also statutory restrictions on foreign ownership of some assets, including banks, airports, shipping and the telecommunications company Telstra. These ownership restrictions are motivated by both economic and security concerns. Recently, the Australian government has flagged electricity generation, transmission and distribution assets as critical infrastructure potentially attracting special ownership restrictions or other conditions to be evaluated on a case by case basis.24 However, this merely confirmed what was already evident from government decisions in relation to Ausgrid that had previously caused confusion (see case study in Appendix 2).

The role of Australia’s Foreign Investment Review Board

The Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB), with a secretariat located within Treasury, advises the treasurer on foreign investment decisions, although this advice is not binding in exercising the treasurer’s powers to reject foreign acquisitions. FIRB in turn takes advice from other government departments, including national security agencies. Recently, there has been an effort to elevate security considerations within FIRB, including through the appointment as FIRB chairman of David Irvine, AO, a former director general of the Australian Security and Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) and the Australian Secret Intelligence Service (ASIS), Australia’s domestic and foreign spy agencies respectively.

More recently, there has been a whole-of-government effort to identify critical infrastructure and improve its resilience through the creation of a Critical Infrastructure Centre (CIC) in the Home Affairs portfolio, which now includes Australia’s intelligence agencies. This effort is supported by new legislation, the Security of Critical Infrastructure Act 2018, which seeks to “manage the complex and evolving national security risks of sabotage, espionage and coercion posed by foreign involvement in Australia’s critical infrastructure”.25 The Act implements a critical infrastructure assets register and gives the minister a last resort power to mitigate national security risks through directions issued to the owner or operator of critical infrastructure. The CIC is designed to complement the work of FIRB and is part of a broader consolidation of national security processes within government under the Home Affairs portfolio.26

The Critical Infrastructure Centre is a welcome development in that it potentially brings a more systematic approach to government policy consideration of assets that might be the subject of potential foreign acquisitions and that raise national security concerns

The CIC is a welcome development in that it potentially brings a more systematic approach to government policy consideration of assets that might be the subject of potential foreign acquisitions and that raise national security concerns. The legislation does not, however, offer much by way of additional certainty for foreign investors, with the register of critical assets not in the public domain. The last resort power is also welcome and provides greater reassurance that critical infrastructure can be placed in foreign ownership without compromising national security.

Reforming Australia’s FDI screening process to improve national security

The FIRB process has often lacked transparency to foreign investors, sometimes appearing arbitrary and capricious in its operation and sending mixed signals. FIRB officials have struggled to communicate the government’s foreign investment policy in clear and consistent ways, implying the policy was not well-defined, even within government.27 The information and data publicly supplied by FIRB has been inadequate in helping the government, parliament and the public understand the process and the nature of foreign investment in Australia.

A number of proposals have been made to reform the FDI screening and approval process in Australia.28 The aim of these proposals is to create a non-discriminatory regulatory framework that provides predictability and certainty for both foreign investors and vendors of Australian assets, enhances Australia’s reputation as an investment destination and maximises FDI inflows while also securing Australia’s security interests.

Narrowing the national interest test

The scope of the national interest test should be narrowed to cover only threats to national security. The concept of the ‘national interest’ should not be trivialised by associating it with issues that are not genuinely national in scope or of vital strategic concern. The national interest test should not be used as an arm of domestic competition, industry or employment policy or serve protectionist objectives such as preventing the offshoring of head office jobs. Nor should it be thought of as a second-best approach to fill gaps or fix problems created by regulatory failure in other areas of public policy such as housing or taxation. These issues should all be addressed behind the border on a non-discriminatory national treatment basis using domestic regulatory frameworks. FIRB already largely defers to domestic regulators in its consideration of these non-security related economic and other policy issues. Enforcement of restrictions on foreign investment in real estate, for example, is now largely the responsibility of the Australian Taxation Office.

FIRB’s primary focus should be consideration of the implications of foreign acquisitions for national security in conjunction with the new Critical Infrastructure Centre. This change would broadly align the mandate of FIRB with that of CFIUS in the United States. Better integrating national security into the FIRB process is a significant challenge that is made more difficult by the government’s foreign investment policy, which includes a laundry list of non-binding policy considerations FIRB must consider and make recommendations on. National security and economic policy issues are not easily reconciled given that national security risks and economic costs and benefits are fundamentally incommensurable as considerations for policy. However, where national security is genuinely threatened, these considerations should dominate economic ones.

The multiple policy considerations that form part of Australia’s foreign investment policy only serve to expand the scope of the treasurer’s discretion over FDI and make for confusion in articulating government policy. Narrowing the scope of the national interest test to national security and delegating other policy issues to post-establishment, behind the border regulation would sharpen the focus of Australia’s foreign investment framework and elevate national security concerns above domestic policy issues.

FIRB should develop broad principles for assessing national security risks and make these principles publicly available. The principles should be suitable for multilateral adoption in free trade agreements and investment treaties. The processes to be followed in applying these principles should be the subject of a publicly available guidance note. In the United States, there is a statutory list of security issues that inform the CFIUS screening process and a publicly-available government guidance document.

FIRB should consider foreign acquisitions based on a threat framework similar to that proposed by Moran and discussed earlier in this report. This would require an overhaul of FIRB to bring in more expertise from the defence and intelligence community at the expense of its current focus on other policy issues that largely duplicates or second-guesses the work of domestic regulators. FIRB should report to the National Security Committee of cabinet rather than the treasurer to ensure a whole-of-government consideration of national security issues.29

The government’s discretion to reject foreign investment applications should be exercised only in relation to national security issues or cases where domestic regulatory frameworks are unable to address policy issues raised.

The government’s discretion to reject foreign investment applications should be exercised only in relation to national security issues or cases where domestic regulatory frameworks are unable to address policy issues raised. Decisions to reject particular transactions should be carefully explained in terms of publicly-available principles and the guidance document. The principles could be harmonised with those used by CFIUS with a view to encouraging their adoption on a multilateral basis and inclusion in free trade agreements and bilateral investment treaties (BITS). Existing agreements often include a national security exception. The principles should govern how the national security exception is interpreted and should aim for a narrow construction that addresses only vital security interests.

The screening process should also seek to examine ways in which security risks can be remediated or otherwise addressed without necessarily rejecting the proposed transaction in its entirety. This may entail specific assets or operations being carved out of a proposed transaction, enhanced governance or security screening requirements. Specific assets may be brought within the scope of the recently legislated last resort power. FIRB should aim to facilitate transactions rather than serving as a bureaucratic roadblock to foreign acquisitions.

Based on the CIC’s Critical Infrastructure Asset Register, assets deemed too sensitive to allow foreign ownership should be identified either through statutory restrictions on foreign ownership or a negative list to increase certainty for foreign investors and ensure there is public scrutiny and debate around the content of the negative list.

The adoption of clear principles and processes for evaluating transactions reduces the risk that national security issues are conflated with other issues or used to serve domestic political and economic agendas that are not related to genuine security concerns. This would support stronger, more reliable and better understood foreign investment decisions by government. A well-defined and transparent process should deter acquisitions that raise security concerns from being proposed in the first place and investment proposals are more likely to be structured to satisfy the Australian government’s concerns.

FIRB could also improve its reporting to parliament. FIRB currently produces an annual report that is neither timely nor particularly informative. A process should be put in place to enable FIRB to brief a parliamentary committee in private on its consideration of national security issues in a way that protects classified and commercially-sensitive information that might not otherwise be made public, with a view to improving parliament’s understanding of the foreign investment review process. By helping parliamentarians understand how the FDI screening process protects national security, it is less likely that cross-border acquisitions will become politicised based on an ill-informed understanding of the review process or the relevant security issues on the part of politicians and the public.

The US regulatory regime for FDI

The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) is the inter-agency body charged with reviewing any merger, acquisition or takeover that would result in foreign control of a US business to determine the effect on the national security of the United States.30 It is chaired by the secretary of the Treasury, and includes secretaries from the departments of Homeland Security, Commerce, Defense, State, and Energy; the offices of the US Trade Representative and Science and Technology Policy; and the Attorney General. The secretary of labor and the director of national intelligence serve as ex-officio members to the committee; while five other executive offices — Office of Management and Budget, Council of Economic Advisors, National Security Council, National Economic Council, and Homeland Security Council — can also observe and participate in the CFIUS process. While CFIUS filings are voluntary, the committee may also initiate a review if it determines the transaction could raise national security concerns.

Following a review, if CFIUS finds the transaction does not present any national security risks, or that other laws provide adequate and appropriate authority to address the risks, CFIUS will conclude its review and provide ‘safe harbour’, meaning the transaction will not be subject to future review. CFIUS will not conclude action on a transaction if there are unresolved national security concerns identified by any CFIUS member. If CFIUS finds that a transaction presents national security risks and that other provisions of law do not provide adequate authority to address such risks, CFIUS may enter into an agreement with, or impose conditions on, parties to mitigate such risks; or it may refer the case to the president for action including a recommendation to block the transaction.31

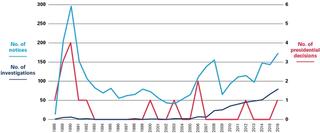

Figure 1: CFIUS number of notices and investigations

The most recent annual CFIUS report to Congress shows an upward trend in the number of notices filed with CFIUS, from 65 in 2009 to 172 notices in 2016 (see Figure 1). During 2016, only one transaction was subjected to a presidential decision. In terms of the acquirer home country, the report shows that acquisitions by investors from China accounted for the largest share of notices filed for the three-year period from 2013-2015, representing 74 of the total of 387 filings over this period. Investors from Canada, the United Kingdom and Japan accounted for 49, 47, and 40 transactions, respectively, over the same three-year period. Together, these four countries accounted for more than half (54 per cent) of CFIUS reviewed filings over this period.

The number of CFIUS filings continues to rise: the committee reviewed a record 172 notices in 2016 versus 143 notices in 2015 and nearly 240 notices in 2017, another record. At the same time, the number of filings requiring full investigations has increased, from just four per cent of filings in 2007 to 46 per cent in 2016 and 70 per cent in 2017. Also, the percentage of notices withdrawn during the CFIUS review process has increased from eight per cent in 2014 up to 16 per cent in 2016. The increased caseload, in combination with a more complicated threat environment as detailed below, has intensified CFIUS’ scrutiny of transactions and extended the typical CFIUS process timeline.

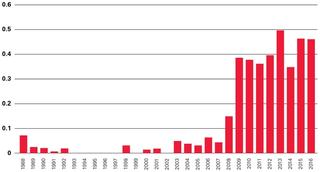

The increased scrutiny applied to foreign direct investment in the United States is evident in the increased ratio of investigations to notices since 2008 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Ratio of CFIUS notices to investigations

An evolving threat

The increase in CFIUS filings as well as the increase in percentage of those filings that advance to full investigations is attributed to a range of factors. In testimony before the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs in early-2018, Heath Tarbert (Treasury’s assistant secretary for international markets and investment policy) said the increased complexity confronting CFIUS is attributable to three key factors: First, foreign governments are using investments for strategic, rather than economic, goals; second, transaction structures are increasingly complex; and third, supply chains are increasingly globalised.32 He also noted the role of data and dual-use technology in contributing to the increasing complexity of transactions reviewed by CFIUS.

China’s rise

While CFIUS legislation does not name specific countries of concern, the CFIUS report to Congress highlights the committee’s coverage of transactions where the acquirer is ultimately controlled by a foreign government; is from a country with a record on “national security-related matters that raise concern”; has a history of taking or intentions to take actions that could impact US national security; and has a history of doing business in sanctioned countries. In that context, the first National Security Strategy (NSS) of the Trump administration flags China (along with Russia) as challenging “American power, influence and interests, attempting to erode American security and prosperity” and refers to some actors’ use of “largely legitimate legal transfers and relationships to gain access to fields, experts, and trusted foundries that fill their capability gaps and erode America’s long-term competitive advantages”.33

The more combative stance toward China coincides with a dramatic increase in the stock Chinese FDI in the United States. Just ten years ago, the stock of Chinese direct investment in the United States — which represents the cumulative value of annual investment flows — totalled US$3 billion; by 2017, the stock of Chinese FDI in the United States was valued at US$138 billion,34 making China the 11th largest foreign direct investor in the United States. On a stock basis, the largest direct investors in the United States are the United Kingdom, Canada, Japan, and Germany, all US allies and countries covered by Collective Defense Arrangements with the United States.35 China’s increasing investment in the United States represents the first time that a top investor in the United States is also considered — according to the NSS — a strategic adversary committed to shaping “a world antithetical to US values and interests”.

Suspicion of China and its motives in expanding economic ties with the United States did not start in the current US administration. In 2012, two separate congressional reports highlighted the potential national security threats posed by Chinese investment. The first, an October 2012 report from the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, detailed “the counterintelligence and security threat posed by Chinese telecommunications companies doing business in the United States” and called on CFIUS to block acquisitions, takeovers, or mergers involving two Chinese telecommunications equipment companies, Huawei and ZTE, given the threat of these companies specifically to US national security interests.36 A second report published in November 2012 by the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission raised concerns about the “potential economic distortions and national security concerns arising from China’s system of state-supported and state-led economic growth” and that state-backed Chinese companies may decide to invest “based on strategic rather than market-based considerations”. This report called for amendments to CFIUS, proposing (1) mandatory CFIUS reviews of all controlling transactions by Chinese state-owned and state-controlled companies wanting to invest in the United States; (2) a net economic benefit test to the current national security test that CFIUS conducts; and (3) a ban on investment in a US industry by a foreign company whose government does not allow foreign investment in that same industry.

Critical and ‘dual-use’ technologies

CFIUS defines critical technologies, with reference to US Export Control regulations, as (a) defence articles or defence services covered by the munitions list set forth in the International Traffic in Arms Regulation; (b) items on the Commerce Control List of the Export Administration Regulations that are controlled pursuant to multilateral regimes, for instance missile technology; (c) items and technology specified in the Assistance to Foreign Atomic Energy Activities and the Export and Import on Nuclear Equipment and Materials regulations; and (d) agents specified in the Select Agents and Toxins regulations.37 However, much of the current debate around the threat posed by foreign investment in critical technologies pertains to the adequacy of the above list to capture emerging critical technologies that may not have existed at the time the regulations were drafted.

In addition, some of the transactions reviewed by CFIUS involve advanced technologies that may (presently or eventually) have both commercial and military applications, so-called ‘dual-use’ technologies. The CFIUS report to Congress highlights that transactions involving such dual-use applications, as well as transactions that might entail a loss in US technological competitiveness that would be detrimental to national security, are among the considerations covered in reviews undertaken by CFIUS.

President Trump’s action in March 2018 to block the acquisition of Qualcomm by the Singapore-based Broadcom was motivated by concerns of future technological competitiveness.

A heightened concern regarding advanced technology transfer to China has been evident in recent years, including in the CFIUS process. President Obama’s December 2016 decision to prohibit the acquisition of the US business of Aixtron, a German firm with assets in the United States, by a Chinese investment firm; and in President Trump’s September 2017 action to block the acquisition of Lattice Semiconductor Corporation by another Chinese investment firm, Canyon Bridge Capital Partners present two recent (and public) examples. President Trump’s action in March 2018 to block the acquisition of Qualcomm by the Singapore-based Broadcom was also motivated by concerns of future technological competitiveness (see Appendix 2).

A further aspect to the debate concerns the government’s ability to identify ex-ante those technologies and transactions that may pose a threat to national security. In this context, a 2017 draft report by the Defense Innovation Unit Experimental (DIUx) details China’s efforts to attain global leadership in emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence, robotics, and augmented reality/virtual reality and financial technology. The DIUx report makes the case that in order to effectively mitigate the potential threat to national security posed by China’s ambitions, CFIUS should be reformed, including by upgrading a Department of Defense (DoD) critical technologies list and making the DoD list the basis for CFIUS reviews (as well as export controls); restricting investments and acquisitions by China in these critical technologies; and expanding CFIUS’s jurisdiction to cover all transaction types (e.g., greenfield investments and joint ventures, whether located in the United States or abroad).

Transaction structure

Increasingly complicated transactions structures may obscure the true ownership of the investing party and/or be designed to get around the concept of ‘control’ that is fundamental to CFIUS jurisdiction, e.g., licensing and contracting arrangements. Treasury officials have confirmed that CFIUS is aware that some transactions may be deliberately structured to avoid CFIUS review, while others are moving critical technology and associated expertise from a US business to offshore joint ventures. While this issue is relevant to the current discussion of CFIUS’s ability to address evolving threats to national security, it is not new. In fact, as originally drafted, the 1988 Exon-Florio amendments to CFIUS would have applied to joint ventures and licensing agreements in addition to mergers and acquisitions. But joint ventures and licensing agreements were ultimately dropped from the legislation because the Reagan administration and various industry groups argued at the time that such business practices were deemed beneficial for US companies. In addition, they argued that any potential threat to national security could be addressed by the Export Administration Act and the Arms Control Export Act.38

Greenfield investment

The DIUx report and others point to the increasing role of start-up or ‘greenfield’ investment by China, particularly in venture capital, to provide China with access to cutting-edge technologies. While China is the primary source of this concern, concerns around greenfield investments falling outside CFIUS jurisdiction first gained prominence following the attempt by the Russian space agency, Roscosmos, to build Global Positioning System (GPS) monitor stations in the United States in 2013. This episode generated interest in amending CFIUS’s jurisdiction to include greenfield investments, a recommendation that has gained additional traction because of the perceived threat stemming from Chinese investment.

Data concerns

The 2018 decision by China’s Ant Financial to abandon its bid to acquire MoneyGram International after failing to get CFIUS approval increased the profile of digital data and its possible national security implications (see Appendix 2). While the US government did not officially confirm that data were at the heart of national security concerns related to the transaction, at least one media outlet’s reference to congressional concerns that “approving Ant’s purchase of MoneyGram might allow ‘malicious actors’ to get hold of financial data belonging to American soldiers and their families” shed light on CFIUS’ assessment of the intersection between digital data and national security. While data and data analytics have been integral to national security analysis for decades, the full scope of data’s relevance to national security, including in the context of foreign investment, is raising questions about how governmental authorities should respond to the potential national security risks posed by access to data as well as the data itself.

Proposed CFIUS reforms

The evolving nature of the potential national security threats stemming from foreign direct investment has led to multiple legislative proposals in the US Congress that aim to close perceived gaps in the current CFIUS regime.39 The broadest proposal, known as The Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act of 2017 (FIRRMA), was introduced in both houses of Congress on 8 November 2017, in companion bills sponsored by Republican Representative Robert Pittenger (H.R. 4311, with 18 co-sponsors) and Republican Senator John Cornyn (S. 2098, with 10 co-sponsors). This legislation represents the most comprehensive reform of the foreign investment review process under CFIUS since the 2007 enactment of FINSA. The Trump administration has also given consideration to blanket restrictions on investment in certain sectors invoking the International Emergency Economic Powers Act 1977.

Left unchanged in FIRRMA are provisions that effectively serve as the core principles of the CFIUS process. The first provision states that CFIUS can proceed into the national security investigation phase only after it has determined during the national security review phase that a foreign investment transaction (1) threatens to impair the national security of the United States; (2) is controlled by a foreign government; or (3) would result in foreign control of any critical infrastructure that would impair the national security of the United States and that the impairment had not been satisfactorily mitigated.

Currently, parties to a transaction provide a voluntary notification to the committee. Under FIRRMA as initially drafted, CFIUS would require a written notification of a transaction in certain cases due to (1) the technology, industry, economic sector, or economic subsector of the US business being acquired; (2) the difficulty involved in remedying the harm to national security caused by the investment transaction; and (3) the difficulty involved in obtaining information on the transaction. FIRRMA would also expand the scope of CFIUS review to include any investment in a US critical technology or a critical technology infrastructure.

FIRRMA as initially drafted would add nine factors to the existing factors the committee and the president may choose to use in evaluating the implications of an investment transaction on US “international technological and industry leadership”.40 This would be a departure from the traditional focus on national security more narrowly defined. Furthermore, FIRRMA would require greater scrutiny by CFIUS of transactions from countries of ‘special concern’ that involve critical technologies or critical materials, including review of firms that provide services or support to entities that are associated with critical technologies or industries.41 Another provision of FIRRMA would strengthen information-sharing with US partners such as Australia and create a ‘safe list’ of certain allied countries, for which these new types of transactions would be exempt from review.42

The Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act has been the subject of numerous congressional hearings and received the vocal support of the Trump administration and multiple Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States agencies, including Treasury.

FIRRMA has been the subject of numerous congressional hearings and received the vocal support of the Trump administration and multiple CFIUS agencies, including Treasury as the CFIUS chair. Certain elements of the legislation have earned near universal support, for instance, the proposal to increase resources allocated to CFIUS agencies in order to keep pace with the increasing number and complexity of transactions to be reviewed by CFIUS; providing CFIUS with jurisdiction over real-estate transactions near military bases or other sensitive government facilities; and making the CFIUS review process mandatory for certain transactions, including those that involve government ownership.

Other proposals included in the draft legislation have received broad support in theory, but observers are sceptical that proposed reforms can adequately address the risk. One example is the proposal to define the list of critical technologies that would be evaluated in the context of a CFIUS review (also relevant to export controls). While there is broad agreement on the need to update the critical technology list, there is widespread scepticism regarding the government’s ability to update the list in a meaningful way given that future applications of emerging technologies cannot be known. Similarly, while there is support for differentiating CFIUS reviews depending on the source of the FDI, the basis for such differentiation is under debate. On increased information sharing among ‘like-minded’ countries, there are questions around how to define a ‘like-minded’ country and how to share information, including information shared on a confidential basis by private-sector entities.

In a move that was likely not a coincidence, House Foreign Affairs Committee Chairman Ed Royce and ranking member Eliot Engel in February 2018 introduced bipartisan legislation, H.R. 5040, the Export Control Reform Act of 2018, as an attempt to modernise US export control regulations of dual-use items. This bill would repeal the lapsed Export Administration Act (EAA) and replace it with a permanent statutory authority to better administer US dual-use and Department of Commerce-licensed military exports. It also stipulates that export controls guarantee enduring US leadership in science, technology, engineering, manufacturing and other such sectors. Also, it provides new authority to classify and appropriately regulate emerging critical technologies. Finally, the bill is an attempt to support US diplomatic efforts to advocate for greater international coordination and cooperation on export controls.43

As of this writing, the prospects for both the FIRRMA and export control legislation remain uncertain, though most analysts expect some version of both bills to eventually be enacted by Congress. Ultimately, it is the implementation of CFIUS — through regulations and presidential action — that may have the greatest bearing on how foreign investment reviews are conducted, notwithstanding any changes to the actual legislation.

Increased coordination between Australia and the United States

The acquisition of the Port of Darwin by the Chinese-owned Landbridge in 2015 became a point of diplomatic friction between Australia and the United States, as much due to a lack of consultation on the transaction and the screening process as the substance of the transaction itself, although specific national security concerns were also raised (see Appendix 2).

This episode argues for a more formal consultative process between Australia and the United States on foreign acquisitions that raise national security concerns. Both Australia and the United States source information from their own intelligence agencies as part of their FDI screening processes. There is already extensive cooperation between US and Australian intelligence agencies through the ‘Five Eyes’ intelligence sharing arrangements, however, FIRB and CFIUS have not traditionally been strong repositories of national security expertise.

Given the often shared and collaborative nature of defence industry development between Australia and the United States, a joint and coordinated approach to protecting technology from appropriation through foreign direct investment makes sense.

A memorandum of understanding between the Australian and US governments could be used to formalise cooperation between the two bodies. The FIRRMA Bill before Congress envisages increased cooperation with allied countries on these issues. This would complement existing ‘Five Eyes’ processes in relation to intelligence sharing. This argues for the creation of an improved capability within FIRB and CFIUS to handle classified information and process it in a way that integrates national security concerns with other elements of the FDI screening process. The more the screening process deviates from narrow security concerns, the more difficult this integration process becomes.

It is possible to imagine situations in which a cross-border acquisition affects assets in both Australia and the United States that raise national security concerns. This scenario may call for a joint FIRB-CFIUS review and a coordinated approach to either remediating or rejecting the transaction. Given the often shared and collaborative nature of defence industry development between Australia and the United States, a joint and coordinated approach to protecting technology from appropriation through foreign direct investment makes sense.

Conclusion

The negotiations over the Australia-US Free Trade Agreement (AUSFTA) nearly failed over US opposition to Australia’s foreign investment screening regime. One of the top US negotiating priorities was in fact the elimination of FIRB, which the United States correctly saw as a vehicle for Australian government protectionism rather than promoting national security.44 The agreement was successfully concluded in 2004 only after Canberra agreed to raise and rationalise its FDI screening thresholds. The AUSFTA set a benchmark for liberalisation of Australia’s screening thresholds that has since been adopted in Australia’s FTAs with other countries and in the context of the Trans-Pacific Partnership. The United States has thus been a force for liberalisation in Australia’s foreign investment regulatory framework.45

There is still much that Australia can learn from the United States in the regulation of foreign investment. The United States maintains a more liberal regulatory framework for FDI that is better focused on national security issues than the Australian process. CFIUS administers a set of statutory principles in relation to national security considerations that could be adapted by FIRB in its scrutiny of foreign investment applications. To date, the United States has resisted giving CFIUS a mandate to consider broader economic policy issues that are more appropriately addressed behind the border by domestic regulatory frameworks.

It is important to focus scarce regulatory resources on genuine risks to national security and not be distracted by the second-order policy issues that have proliferated in the Australian government’s foreign investment policy.

The United States and Australia have struggled to re-define their approach in response to the national security issues raised by China’s increased role in foreign investment and the relationship of that investment to its mercantilist industrial policies and increasingly assertive military posture. In this environment, it is important to focus scarce regulatory resources on genuine risks to national security and not be distracted by the second-order policy issues that have proliferated in the Australian government’s foreign investment policy. These non-security related policy considerations largely duplicate or second-guess domestic regulatory frameworks that already operate behind the border to regulate business investment. Screening acquisitions at the border based on these policy considerations adds little that is useful to the regulation of business investment in Australia and provides a vehicle for political interference in cross-border transactions that is mostly detrimental to Australia’s reputation as a reliable destination for foreign investment.

The principle that the economic regulation of FDI is best implemented behind the border also applies to national security regulation. National security needs to be achieved behind the border over time and not at the border at a particular point in time. Blocking transactions at the border may give a false sense of security in relation to risks behind the border that may arise independently of foreign ownership. Addressing these risks is a task for domestic law enforcement, security and intelligence agencies. Better resourcing of those agencies would do more to secure Australia’s vital national interests than additional resources devoted to screening foreign acquisitions that for the most part do not represent national security risks.

Appendix 1: Comparison of FDI screening and approval processes, Australia and the United States

| AUSTRALIA | UNITED STATES | |

|---|---|---|

| Legislation |

|

|

| Mandate |

|

|

| Scope |

|

|

| Process and fees |

|

|

| Key thresholds triggering regulatory review |

|

|

| Decision-making authority |

|

|

| Timeframe |

|

|

| Statistics on cases |

|

|

Appendix 2: Case studies

The following case studies highlight some of the issues of policy and process raised by previous foreign investment transactions and help identify the scope for improving the FDI screening process.

Australian case studies

Australian entity: OZ Minerals

Foreign entity: China Minmetals Corporation

Date: 2009

China Minmetals Corporation, a Chinese SOE, sought to purchase OZ Minerals, an Adelaide-based copper and gold mining company for A$2.6 billion. Treasurer Wayne Swan rejected the sale in March 2009 on national security grounds, citing OZ Minerals’s holding of the Prominent Hill Mine, which is located within the Woomera Prohibited Area military testing zone in South Australia. The Woomera Prohibited Area is the largest military zone in the world, covering 130,000 square kilometres, or roughly the size of England and is used to test guided missiles, unmanned aerial vehicles and electronic warfare systems. According to journalist David Uren, the transaction was rejected even though:

- China Minmetals Corporation had initially been told by the Australian Defence Department that it had no objections to the sale;

- the Woomera weapons testing zone is 160 km away from the mine;

- the proposal stipulated that the company intended to maintain the OZ Mineral’s Australian management and staff; and

- companies operating in military zones are required to allow any military inspection of their location, equipment and personnel at any time.46

A revised investment proposal was approved in April 2009 after the Prominent Hill Mine was excluded from the transaction and numerous non-security related conditions were attached to the approval that were explicitly protectionist in intent.47 There was considerable speculation around the treasurer’s motives for blocking the initial acquisition. This speculation points to a lack of clarity about the role of national security in the FDI screening process. The Australian government’s security concerns were not well flagged to foreign investors, while the advice the government received seems to have been inconsistent with the foreign investment decision taken.

Australian entity: Ausgrid

Foreign entity: State Grid Corporation and Cheung Kong Infrastructure

Date: 2016

The Chinese government-owned State Grid Corporation and Hong Kong-based Cheung Kong Infrastructure were bidders for a 99-year lease over a 50.4 per cent stake in New South Wales electricity distributor Ausgrid in a sale that was expected to be worth around A$10 billion to the state government.

The deal was rejected at the last minute by the federal treasurer, citing national security concerns, a decision that had bipartisan political support at the federal level. The decision came as a surprise given that the sale process had proceeded to an advanced stage before the foreign investment decision was made, with bidders having previously been given a green light from the federal government. State Grid operates electricity infrastructure globally and elsewhere in Australia. The government did not elaborate on the national security concerns at the time of the transaction.48

It has since been revealed that at the last minute the Australian Signals Directorate identified that Ausgrid hosts infrastructure supporting the Australia-US Joint Facility at Pine Gap, part of the US strategic nuclear early warning system and also an essential element of Australia’s intelligence gathering.49 The late identification of this security issue exposed weaknesses in the foreign investment review process, in particular, which federal government department was responsible for critical infrastructure. This episode became part of the impetus for the formation of the Critical Infrastructure Centre.50 It also informed changes to the government’s foreign investment policy to specifically flag electricity-related assets as critical infrastructure likely to give rise to increased scrutiny and special conditions for foreign acquisitions.

Australian entity: Northern Territory Government/Port of Darwin

Foreign entity: Landbridge Corporation

Date: 2015

The Landbridge Corporation, a privately-owned Chinese company, purchased a 99-year lease over the Port of Darwin from the Northern Territory government for A$506 million. Because the vendor was a territory government, the transaction was not subject to the usual scrutiny from the Foreign Investment Review Board, a loophole that has since been closed.

The sale, at least initially, raised no objections from the Australian Defence Department, although its consideration of the transaction only encompassed the issue of maintaining access for the Australian Defence Force, not wider security concerns. The US government was surprised and reacted adversely due to a lack of consultation by the Australian government. The port’s proximity to Australian and US forces based in Darwin, as well as a sensitive communications cable, potentially raises national security issues, in particular, whether Chinese ownership could facilitate intelligence collection on the deployment of Australian and US forces.51

The transaction was the subject of an Australian senate inquiry that exposed significant weaknesses in the way in which national security considerations were addressed by the Australian government.52 Whatever the merits of the security concerns raised by the acquisition, these issues were only seriously considered and debated after the transaction was announced. The Port of Darwin case also points to a failure of consultation between Australian and US authorities, highlighting the need for greater coordination on these issues. This episode highlights the need for security considerations to be elevated and better integrated into the FIRB process, as well as better consultation with the United States.

Australian entity: Cable & Wireless Optus Limited

Foreign entity: Singapore Telecommunications Limited (Singtel)

Date: 2001

Singtel, a state-owned Singaporean company, sought to purchase Optus, a private UK-owned telecommunications company that was the second largest telecommunications company in Australia, for A$17.2 billion. At the time, the transaction was the second largest corporate deal in Australian history.

A national security issue arose in that Optus-operated satellites used by the Australian Department of Defence. This issue was addressed by Optus agreeing to a number of conditions, including an agreement signed between the Defence Department and Singtel mandating relevant personnel obtain security clearance and that the Australian government could control the satellite networks in the event of a national security emergency. The United States, which supplied the satellite equipment, also gave its approval for the deal by stating that a US export license was unnecessary.

The deal encountered objections from some defence analysts and some in the business community. A mitigating factor was that control was passing from one foreign company to another and these entities resided in countries with which Australia has traditionally enjoyed a close security relationship. Australia was also hoping to expand its already positive relationship with Singapore with a free trade agreement, which was signed shortly after the deal.

This transaction would seem to provide a good model for how the FDI screening process should operate. The security concern was clearly identified and articulated by the Australian government, allowing the parties to the transaction to put in place arrangements that satisfied Australian government concerns, enabling the transaction to proceed. There seems to have been effective coordination with US authorities in this case.