Executive summary

Chinese authorities have hinted that they may use their dominant position as a supplier of rare earths and associated manufactured goods to retaliate against US restrictions on high technology exports to China. China is responsible for between 80 and 90 per cent of processed rare earths and products such as powerful rare earth magnets.

It is not in China’s interests to impose an embargo — the result would be the stimulation of competitive rare earths production and substitution. China’s rare earths companies are aware of the risks of pushing prices too high, because they’ve done it before in 2010. It seriously damaged the market. Total sales took a decade to recover, and for some rare earth elements, the damage has been permanent as substitutes have been found.

While rare earths have lots of promise, with the shift to electric cars and the continuing rollout of wind farms driving demand, there are good reasons why it has been hard to get rare earth projects developed. There are no transparent prices, separating the elements out of the host rock is technically difficult, often yielding radioactive waste, and the applications for rare earths are subject to unpredictable technological change. Also, any investor in a non-Chinese rare earth project must make a calculation about the response from its giant Chinese competitors.

Given the intensity of the US-China trade war, the Trump administration has resolved that it is a national security priority to eliminate the dependence of the US military on Chinese supplies of critical minerals, particularly rare earths and derivative products.

The Japanese government decided in 2010 that these risks justified government intervention. Australia’s Lynas, which now accounts for 8 per cent of global rare earth production, was a key beneficiary, with Japanese government funding supporting its development.

The United States has preferred to leave it to the market but given the intensity of the trade war, the Trump administration has resolved that it is a national security priority to eliminate the dependence of the US military on Chinese supplies of critical minerals, particularly rare earths and derivative products. The president has committed to provide financial assistance under the Defense Production Act, although the sums advanced under this are typically too modest to support a resource project development.

The Australian government is considering its response to the US push for non-Chinese sources of supply. Australia has at least half a dozen rare earth projects ready for development but needing commitments from potential customers and financiers. Neither banks nor equity markets will finance them. The Australian government could, at a stretch, use the “national interest account” at Export Finance Australia to assist. The Commonwealth, rather than the agency, would assume responsibility for any losses. The government has already used that account to establish A$3.8 billion facility to support its military equipment export program. However, it would have to go into any such commitment with its eyes open to the possibility of losses to the taxpayer — rare earths have often been in over-supply with poor prices.

It may be that the most promising source of commercial finance for developing Australia’s rare earth deposits comes from China, which is forecast to become an importer over coming years as growth in demand from its rare earths manufacturing outstrips supplies from its own mines. Chinese investors already have substantial stakes in some of the most promising Australian developments. The Foreign Investment Review Board should remain open to Chinese participation in Australia’s rare earths industry.

Introduction

Chinese authorities have made veiled threats that they will use their dominant position in the rare earths industry to withhold supplies to the United States in retaliation for moves by the US administration to ban sales of high-technology goods to China.

Building a dominant position in rare earths and their downstream products has been a strategic objective for the Chinese state ever since the mid-1980s. China is currently responsible for roughly 70 per cent of global mine production, 85 per cent of the initial processing of them into oxides and 90 per cent of the production of metals, alloys and magnets.1

But do these strengths give China the ability to bring the western technology companies that depend upon supplies of rare earth materials to their knees? When China exercised its market muscle in 2010, curbing shipments to Japan, Europe and the United States with export quotas, export tariffs and an informal embargo, it sent global prices for key rare earth compounds skyrocketing.

US, Japanese and European authorities were shocked and embarked on strategic reviews of their vulnerabilities. Over the past nine years, China’s share of mine output has been diluted as Australian and United States production has been brought on stream, alongside smaller increases in output elsewhere in Asia, Africa and Latin America.

If Western governments are uncomfortable with leaving the sourcing of rare earths and their downstream products to market and/or Chinese forces, there are many entrepreneurs eager to develop rare earth resources if only they could obtain the finance and committed customers.

Many more projects are in various stages of development. But the continuing high dependence on China for rare earth processing and derivative manufactured goods has Western governments worried once again. They are reviewing their strategic options.

This report argues that any attempt by China to impose an export embargo on rare earths or downstream products would be the catalyst for the development of non-Chinese production and substitution that would ultimately weaken China’s strong position in the market.

The 1973 oil embargo by OPEC provides a lesson. On the eve of the crisis the OPEC nations were producing 1,500 million tonnes of oil a year while the rest of the world’s output was 1,400 million tonnes. Within a decade, OPEC annual production had dropped to 850 million tonnes while the rest of the world’s output had soared to 2,000 million tonnes.2

The Chinese rare earths industry is aware of the risk of pushing prices too high, making it unlikely that Chinese authorities would attempt any repetition of the 2010 squeeze on global supplies. However, it is possible shipments to US customers could be disrupted in a deteriorating trade conflict.

China’s longer-term interest is better served by continuing to build on the comparative advantage it has already achieved in this high-technology niche of the resources industry.

If Western governments are uncomfortable with leaving the sourcing of rare earths and their downstream products to market and/or Chinese forces, there are many entrepreneurs eager to develop rare earth resources if only they could obtain the finance and committed customers.

It was the provision of concessional debt finance backed by Japanese authorities and a sales agreement with Japanese buyers in the wake of the 2010 crisis that made possible the development of Lynas’s rich deposit at Mt Weld in Western Australia. It now provides 8 per cent of global rare earth mine output and operates a large processing plant in Malaysia. The US government is taking tentative steps to deliver financial support to the rare earths industry.

However, governments would have to go into any rare earths ventures with their eyes open to the possibility of losing money. The history of rare earths is that they are often in over-supply with low prices leaving many operators struggling to make a profit.

Australia’s government policy should be flexible. Australia is mindful of the concerns of its ally, the United States, about the security of its supplies and has established a taskforce under the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet to prepare Australia’s response. It should be ready to match any US initiatives to source supplies in Australia with tangible support.

However, it should also be aware that China’s manufacturing of products incorporating rare earths is about to outstrip its own supplies, which would lead to China becoming a net importer. It may be that the best prospect for financing the development of Australia’s incipient rare earth projects rests with China, a possibility that the Foreign Investment Review Board needs to consider. Australia’s national security is not jeopardised by Chinese participation in Australia’s rare earths industry, any more than by its participation in iron ore or coal sectors.

It may be that the best prospect for financing the development of Australia’s incipient rare earth projects rests with China, a possibility that the Foreign Investment Review Board needs to consider.

This report is organised as follows:

- The first section puts the current threats to use rare earths as a weapon in the trade war between the United States and China into the context of China’s previous use of trade restrictions as an instrument of foreign policy. It argues that a formal trade embargo on rare earth exports to the United States is unlikely but that some disruption to shipments is possible.

- The second section examines the consequences of China’s squeeze on rare earth global supplies in 2010. Soaring prices encouraged widespread substitution and efficiency drives by consumer industries that slashed global demand which, for some rare earth products, has never recovered. It also led to the development of non-Chinese supply, including a decision by the Japanese authorities to finance the development of the Mt Weld deposit in Western Australia, owned by Lynas. The effect of slumping demand and a surge in supply was that prices crashed.

- There are more than half a dozen listed Australian companies with proven rare earth deposits that are chasing customers and finance to develop their projects. The third section highlights the hopes and difficulties they confront.

- The rapid development of electric motor vehicles and wind farms holds out the promise of strong growth in demand for rare earths for magnets. However, the rare earths market carries high risks:

- There is no transparent market pricing,

- The technology for processing rare earths can be unreliable,

- Demand for rare earths can swing dramatically with technological change, and

- The dominant participants in the market are Chinese enterprises — some state owned — that may not respond to market signals. - The fourth section compares the strategic responses of Japan and the United States to China’s dominance of the rare earths industry. Japan, with a long history of resource vulnerability and state economic intervention, has found it easier to marshal resources for both financing new supplies and research into substitution and recycling. The United States has preferred market-based solutions, however, in the context of rising geopolitical tensions, the United States now sees breaking its dependence on China for rare earths as a national security priority.

- Finally, Australia’s national interest is to see its rare earths projects developed ahead of competitor projects in other parts of the world. Under existing industry policy, the most important government contribution is ensuring an efficient approvals process for project development and supporting the provision of infrastructure. If development of projects is made a national security priority in the context of Australia’s alliance with the United States, there is potential to use the Export Finance Australia’s special ‘national interest’ account. Any such move would have to be in the context of firm customer contracts and would carry the risk of taxpayer loss. Australia’s Foreign Investment Review Board should also be open to further Chinese involvement in developing rare earth projects.

What are rare earths?

Rare earths — a set of 17 metal elements — have a wide range of high technology applications, from making powerful magnets, to separating petrol and plastics from oil, the treatment of kidney disease, making coloured or optically clear glass, raising the melting temperature of turbine blades and generating white phosphor for LED lights and screens. Their unusual chemical properties stem from their ability to give up and accept electrons. Military applications include missile guidance systems, lasers that penetrate water, night vision goggles and electronic communications systems that are impervious to jamming.

Each of these applications uses only small quantities of rare earths. The total global production is only around 170,000 tonnes or roughly half the output of tin, and the total value of the market is only about US$4 billion globally. Although the United States is dependent on imported rare earth compounds, its purchases of rare earth oxides are only around US$150 million a year, which is almost a rounding error in the context of US imports in excess of US$2 trillion. US imports of manufactured goods containing rare earths are much higher than imports of the oxide raw material. The special qualities rare earths bring to manufactured goods can be difficult to replace.

About half the economically recoverable reserves of rare earths are in China (while around 3 per cent are in Australia). Only a minute portion of reserves is mined — Australia’s reserves could supply the world’s needs for decades.

While the spread of applications is remarkable, it is the use of two of the 17 elements — neodymium and praesodymium — to make powerful permanent magnets that accounts for as much as 90 per cent of the total market by value.3 An NdPr magnet is about seven times more powerful than a simple iron magnet. Electric motors work with either electric (copper coils) or permanent magnets, but the latter are lighter and favoured by most makers of electric motor vehicles and wind turbines. Both electric cars and wind turbines are markets with strong growth prospects.

Geologically, rare earths are relatively common — on a par with nickel or tin. About half the economically recoverable reserves of rare earths are in China (while around 3 per cent are in Australia). Only a minute portion of reserves is mined — Australia’s reserves could supply the world’s needs for decades.

The rare earth elements are found in rock, mineral sands and clays, with most of the 17 elements (which are actually metals, not earths) bound in the same mineral structure. Separating the diverse elements is difficult, expensive and, depending on the orebody, can produce large volumes of toxic and often radioactive waste. With the total market relatively small, they are hard to develop profitably.

Table 1: List of rare earths and their applications

|

Rare earth elements |

Atomic symbol |

Application |

|

Lanthanum |

La |

Cracking catalysts in petroleum refining, lasers and green phosphors. |

|

Cerium |

Ce |

Glass polishing, catalysis and component in phosphors. |

|

Praesodymium |

Pr |

Pigment (yellow), optical properties in fibre and magnets. |

|

Neodymium |

Nd |

Permanent magnets, lasers and filters in welding goggles. |

|

Samarium |

Sm |

Permanent magnets, lasers, and optical and microwave devices. |

|

Europium |

Eu |

Phosphors. |

|

Gadolinium |

Gd |

Phosphors and scintillation agents, and Co medical X-rays. |

|

Terbium |

Tb |

Phosphors, lasers and magneto-optic recording systems. |

|

Dysprosium |

Dy |

Additive to Nd magnets to improve temperature properties. |

|

Holmium |

Ho |

Strong magnetic and microwave properties — niche scientific uses. |

|

Erbium |

Er |

Phosphors, fibre-optics and lasers. |

|

Thulium |

Tm |

Lasers, magnetic and microwave uses. |

|

Ytterbium |

Yb |

Silicon photocells and strain gauges. |

|

Lutetium |

Lu |

X-ray phosphors and X-ray detectors. |

|

Yttrium |

Y |

Phosphors and microwave generators. |

|

|

||

The rare earth weapon

There is a long history to the use of trade embargoes for political ends. The US embargo on oil shipments to Japan in 1941 was one of the catalysts for Japan’s Asian war, while France attempted to impose an embargo on trade between Europe and the United Kingdom in 1806 in an effort to force a British surrender in the Napoleonic wars. More recently, the Arab oil exporting nations embargoed oil shipments to nations seen to have supported Israel in the Yom Kippur war in 1973, while Russia has, on several occasions, suspended gas shipments to Ukraine.

In contrast to this history, China’s use of trade embargoes as a foreign policy weapon has been ambiguous, with neither clear threats nor objectives.

President Xi Jinping’s tour of east Chinese provinces in late May was a long time in the planning and his whistle-stop tour of the JL Mag Rare Earth Company in Jiangxi had likely been on the schedule well before US President Donald Trump signed an executive order effectively barring US technology exports to Huawei a week earlier. The Chinese leader praised the permanent magnet manufacturer’s commitment to scientific research while recognising its efforts at environmental protection. He did not mention the trade war. The simple fact of his visit was sufficient to draw everyone’s attention to China’s potential to use its dominant position in rare earths and their downstream products to retaliate over Huawei.

The key economic planning body, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), made the threat more explicit a week later, distributing a bulletin quoting an unnamed official in a scripted Q&A. “Will rare earths become China’s counter-weapon against the US’s unwarranted suppression? What I can tell you is that if anyone wants to use products made from rare earth to curb the development of China, then the people of the revolutionary soviet base and the whole Chinese people will not be happy.”4 In other words, if the United States was going to ban the export to China of technology that used Chinese rare earth products, then the United States could not expect China to continue supplying them.

Table 2: Rare earth production by region ('000 tonnes), 2010-2018

|

Region |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

|

Africa |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.01 |

0.70 |

|

Asia (excl. China) |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

2.1 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

|

Australia |

- |

- |

- |

1.1 |

7.2 |

10.5 |

13.8 |

17.3 |

19.1 |

|

China |

176.9 |

185.4 |

174.4 |

171.0 |

156.5 |

148.2 |

137.4 |

132.8 |

127.9 |

|

Europe |

1.5 |

1.4 |

2.1 |

1.4 |

2.1 |

2.3 |

2.5 |

2.8 |

2.8 |

|

North America |

3.0 |

3.7 |

2.5 |

3.6 |

4.8 |

4.0 |

- |

- |

5.2 |

|

South America |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.6 |

1.0 |

2.5 |

|

Total |

181.9 |

191.0 |

179.5 |

177.7 |

171.2 |

165.7 |

156.4 |

155.8 |

160.2 |

|

|

|||||||||

The People’s Daily editorialised that the United States should not underestimate China’s ability to fight the rare earth trade war saying, “don’t say we didn’t warn you”. The nationalist daily, Global Times, explained that “those familiar with Chinese diplomatic language know the weight of this phrase”. It was used by the People’s Daily ahead of China’s 1962 war with India and before its 1979 war with Vietnam.5

But, as is often the case in China, the threats were vague and qualified. The foreign ministry’s spokesman Lu Kang said Xi Jinping’s visit to the permanent magnet factory was routine. “Inspection by China’s state leaders to relevant industries is very normal. Please do not read too much into it,” he said.6

The NDRC did not follow up with any specific threats. The trade conflict was not mentioned at an NDRC conference on rare earths a week later. An official there canvassed the introduction of export controls, but the focus was on curbing illegal rare earth operations and environmental quality control, rather than gaining an edge over the United States.

However, China is holding its options open. When, in late July 2019, the United States announced it would impose 10 per cent tariffs on all remaining Chinese imports, the Rare Earths Association released a statement declaring that the industry would “unswervingly” support China’s counter-measures against the United States and was fully aware of the implications of exporting rare earth products.

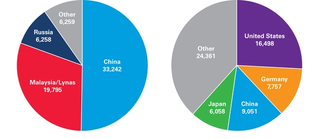

Figure 1 (left): Rare earth exports (tonnes), 2018-2019

Figure 2 (right): Rare earth imports (tonnes), 2018-2019

There was similar ambiguity the last time China was tempted to use its economic power in the rare earths market. It is widely accepted that China imposed an embargo on rare earth exports to Japan in the middle of a heated dispute over the sovereignty of disputed islands in September 2010. Japan’s industry minister Akihiro Ohata reported he had heard from trading firms that Chinese exports of rare earths had been halted.7 China’s premier Wen Jiabao emphatically denied any official embargo with commerce minister Chen Deming telling a sceptical media that trading companies may have independently chosen to suspend exports to Japan. However, the idea of an embargo took hold, with New York Times columnist Paul Krugman declaring “the incident shows a Chinese government that is dangerously trigger-happy, willing to wage economic warfare on the slightest provocation”.8

The US government was more equivocal. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton commented: “The Chinese claim that they did not in any way interfere with the delivery and the continuing exporting of rare earth minerals. Whether or not their motivation was as they describe it or as the Japanese fear it, the fact is they control the vast majority of the supply. That’s not healthy. So, in effect, the Chinese action was a wake-up call to the rest of the world. Now you see Japan and Vietnam cooperating; you see Australia moving forward; the United States is looking at our potential deposits. I think that’s a good outcome of what may have been an inadvertent effort to send a message to Japan.”9

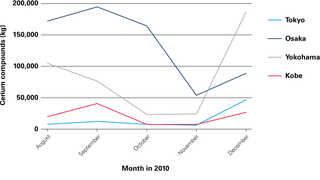

An analysis of shipments through the four main Japanese ports in September, October and November of that year shows the flow of rare earths was volatile — shipments of cerium compounds soared through Osaka in September but plunged in Yokohama. Although shipments overall were lower in October than in September, there was an increase for about a fifth of the various rare earth lines that China sells to Japan.10

Figure 3: Japan's rare earth imports during the 2010 'embargo'

Although this may seem like a historical detail, the pattern of the 2010 incident may be a guide to future action by China. There may be no overt ban on shipments of rare earth related products to the United States, but importers may find they become less reliable and take longer, particularly if there are specialised products with narrow uses in defence related applications.

In a similar manner, Australian coal exporters have been frustrated by delays in landing at China’s ports since February 2019. While there have been official Chinese denials of any politically motivated bans, many in the coal industry believe the purchases of Australian coal were deliberately slowed as an expression of Chinese disappointment with Australia’s stance on a range of bilateral issues.

There are other cases of China deploying informal trade restrictions as an arm of foreign policy. Chinese imports of Norwegian salmon collapsed in 2011 following the award of the Nobel Peace Prize to a Chinese dissident in 2010, while tourism to South Korea plunged following the sighting of US missiles near the North Korean border. Philippine banana and pineapple exports to China were also targeted in the wake of a United Nations Law of the Sea ruling in the Philippines favour in 2016.

There may be no overt ban on Chinese shipments of rare earth related products to the United States, but importers may find they become less reliable and take longer, particularly if there are specialised products with narrow uses in defence related applications.

Chinese shipments of rare earths to Europe and the United States also slowed in September, October and November of 2010. Some saw political motive in this — was the United States being punished for launching an action in the World Trade Organization (WTO) against China’s imposition of increasingly tight export quotas and steep export tariffs on rare earths?11

What was unarguably at work from the mid-2000s was a strategy to limit exports of lightly processed rare earth compounds in favour of building the country’s domestic manufacturing capability. The story of embargoes on Japanese rare earth imports hit an already tight market because of China’s export curbs. When businesses and governments sought to guard against future disruptions by stockpiling supplies, they sent prices soaring. The threat, as much as the reality, of an embargo can be the trigger for a reaction if the market believes it is serious.

The 2010 market squeeze and its aftermath

The few years following the global financial crisis were a period of extraordinary turmoil in resource commodity markets generally with prices soaring, driven by China’s phenomenal stimulus efforts and the slashing of global interest rates. Copper, which had spent most of the previous 15 years hovering at around US$1 a pound shot to nearly US$4 in 2010 while gold was on its way to its 2011 zenith of US$1,900 an ounce. There was a widespread belief, shared at the time by Australian policymakers, that resources were headed for a period of long-lasting scarcity as the industrialisation of emerging nations, led by China, outstripped the capacity of the resources industry to respond.

China had been gradually lowering its rare earth export quotas which came down from 51,000 tonnes in 2005 to 45,000 tonnes by 2007. The objective was to favour local manufacturers. The export quotas then started to be squeezed much more aggressively, dropping to 31,000 tonnes in 2009 and just 24,000 tonnes in 2010.

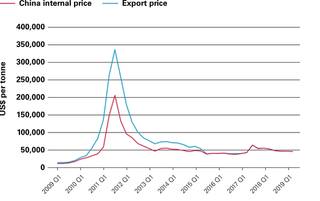

The scramble for supplies sent prices for the various rare earth elements up between three and nine-fold. The elements used for magnets jumped from around US$40 a kilogram to about US$500. Another rare earth, dysprosium, used for magnets that have to operate at high temperatures, leapt from US$170 a kilogram to US$1,600. Even cerium oxide, which is one of the most abundant of rare earths and used for polishing glass and as a phosphor in lighting and screens, rose more than threefold from US$30 to US$100 a kilogram.12

Figure 4: Neodymium oxide price (US$ per tonne), 2009-2019

Consumers started hunting for substitutes. The cerium market has never recovered. Glass manufacturers switched to zirconium as a polishing agent while the replacement of fluorescent tubes by LED lights decimated its other major market. It now sells for around US$2 a kilogram and Chinese research and development institutes expend significant efforts trying to find viable commercial uses for it. Magnet makers also found they could use less rare earths, while technology for recycling rare earth products advanced. Alternative magnets were developed, although with compromises on properties such as weight or strength. Production of rare earth magnets dropped from 85,000 tonnes in 2010 to 60,000 by 2013 and did not recover until 2016.13 It was not until 2018 that total world demand for rare earths matched 2010 levels.

The lesson from the 1973 oil crisis was clear, introducing to the advanced world a new ethos of energy efficiency. In the United States, petrol consumption per person has dropped by a third, while programs initiated in the 1970s ultimately contributed to the research that led to breakthroughs in drilling and fracturing shale deposits.

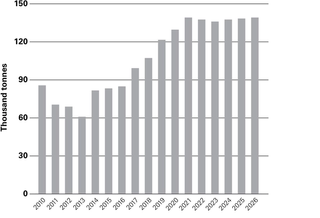

Figure 5: Global rare earth magnet demand ('000 tonnes), 2010-2026

While consumption was falling, China’s efforts to restrict supply were not going so well. The WTO action initiated by the United States was joined by Japan and the European Union. Although the WTO treaty was primarily about lowering barriers to imports, it included a bar on the use of export quotas. Exceptions were allowed for the preservation of natural resources, and China argued this point, saying the export restrictions were designed to protect the environment. However, the WTO found they were effectively an industry protection policy favouring domestic users of rare earths. China appealed but lost in 2014, and was ordered to remove both its export quotas and tariffs. In a victory for the WTO dispute settlement mechanism and the force of its trade rules, China abided by the finding rather than court retaliation. The WTO’s authority is being challenged by the trade conflict between the United States and China, but it continues to provide a vehicle for disciplining the use of export quotas.

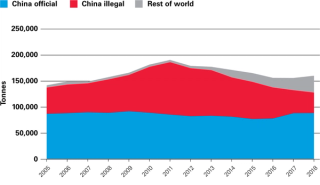

Supply responded to the price shock of 2010, with the biggest boost coming from China itself, where illegal production leapt from an estimated 66,000 tonnes in 2008 to around 95,000 tonnes by 2011, at which point it outstripped China’s official production.14

While the squeeze on rare earth supplies affected consumers in the United States and Europe, it was the Japanese who responded most forcefully. The government funded the state-owned resources company, Japan Oil, Gas and Metals Exploration Corporation (JOGMEC) to support the development of rare earths mines. The Japanese government set aside US$1.25 billion to mitigate future disruptions, with US$490 million allocated towards technological innovation for recycling and improved efficiency and US$370 million to supporting offshore rare earth mining ventures.15

Figure 6: Global rare earth oxide production, 2005-2018

Australia was a key target, with foreign minister Seiji Maehara visiting shortly after the crisis with China. “Australia stands ready to be a long-term, secure, reliable supplier of rare earths to the Japanese economy in the future,” Prime Minister Kevin Rudd told him.16 The following year, Japanese conglomerate Sojitz and Australian rare earths developer Lynas announced a deal, financed by JOGMEC, in which low-interest debt totalling US$250 million would be provided to fund development of a mine at its Mount Weld deposit in Western Australia and processing plant to be located in Malaysia, with Japanese rare earth customers guaranteed an offtake of a minimum 9,000 tonnes. Offers of Japanese funding were also extended to rare earth developments in Vietnam, Kazakhstan and the United States.

The mothballed Mountain Pass mine in the United States had been sold in 2008 to an investment group which assembled funding to restart mining and processing, with a supply agreement to deliver rare earths to a US firm that supplied catalysts for the oil refining industry. Sumitomo and Mitsubishi both offered funding to support the development but withdrew when they could not line up Japanese customers, however the mine recommenced operations in 2012.

By 2014, both Molycorp and Lynas had helped lift non-Chinese production from 4,500 tonnes to 14,000 tonnes. China was still dominant. As the country lost its fight before the WTO, it increased its domestic production quotas and, combined with the illegal Chinese production, the reduced global market was heavily oversupplied and prices crumbled.

Molycorp was forced into bankruptcy by 2015 and suspended operations while Lynas was only kept alive by the steadfast support of its Japanese financiers who were determined to preserve a non-Chinese source of supply.

Some suggest the Chinese engineered the surplus to crush competitors, but with the collapse in demand, it was not until 2016 that its exports surpassed the level of 2009, while the surplus was fed by illegal production that Chinese authorities were demonstrably trying to control. Having lost the case before the WTO and been forced to remove export quotas and tariffs, it was not surprising that exports rose and prices fell.

Rare earths mining has been barely profitable for most of the major Chinese producers over the past nine years.

A constant complaint in China’s academic economic literature is that the country has been unable to extract economic rents from its dominant position in the rare earths market. In the Chinese rare earth industry, the saying is that the international market delivers “cabbage prices”.17

Rare earths mining has been barely profitable for most of the major Chinese producers over the past nine years. A share index of 50 Chinese companies with rare earths interests boomed along with the rest of the Chinese sharemarket in 2015, but was in decline and below 2014 levels until earlier this year, significantly lagging the market index, when the Chinese government acted to stop imports of rare earths from Myanmar, most of which was illegal Chinese production being reimported. This supported domestic Chinese rare earths prices.

An analysis by Perth USAsia Centre’s Jeffrey Wilson argues the 2010 crisis and its response shows China does not have the capacity to impose an effective embargo. To do so would require that:

- Demand was inelastic,

- China had a monopoly on supply, and

- It had the institutional capacity to impose an embargo.

The experience in the wake of the 2010 crisis is that substitution was widespread, alternative supplies were developed, and China in any event was unable to control market supplies of illegal production.18 Any attempt to target just the United States could be readily circumvented by diverting supplies to customers such as Japan.

Chinese producers are mindful of this experience. The deputy secretary general of China’s Rare Earth Society, Zhang Anwen, set out the tensions in rare earths pricing in a recent TV interview. “If the price is too high, the downstream enterprises can't afford it, and they will switch to other substitutes.”19

Zhang’s aspiration is for a price which captures the costs of environmental protection and taxes while providing a decent profit margin for miners, processors and manufacturers, but he acknowledges that competition from black-market producers remains a problem.

China’s focus is on downstream processing. Increasingly, it is not just producing the permanent magnets, but also the electric motors and other devices that use them. There is a similar priority given to producing lasers, MRI scanners, lighting and the multitude of other manufactured goods using rare earths. In China’s state-directed economic model, rare earths and their downstream products are seen as a point of comparative advantage in a high technology niche. With a substantial investment in research and development, China has been filing more rare earths related patents than the rest of the world combined since 2011.

Although Chinese producers are increasing their production, the UK-based specialist resource consultancy Roskill anticipates the country will be a consistent net importer of rare earths by the early 2020s. Chinese investors already have stakes in rare earth ventures in other countries, including in Australia. They are likely to be a source of support for the development of new mine supplies.

Australian prospects in a difficult market

The rare earths price boom of 2010-2011 sparked a rush of investor excitement with one count reaching 400 listed companies around the world with rare earth prospects.20 Of these, only Lynas has gone through the transition from hopeful to significant producer, while the Mountain Pass mine in the United States, which had been mothballed since 2002, was brought back into production. There are still 30 to 40 listed companies with ambitions to bring on rare earth prospects around the world, with around a dozen in Australia.

Australia has a substantial history of rare earth mining — Geoscience Australia records that the first rare earths mine in the country was established in 1913 near Marble Bar in the Pilbara, at a time when the main applications were making flints and mantles for gas lanterns.21 Australia was the world’s leading producer of monazite — a rare earth rich host mineral — in the mid-1980s, but production came to a halt in 1995 when the French company which was processing it, Rhone Poulenc, could no longer obtain permits in France for storing radio-active waste.

Geoscience Australia estimates that Australia has resources equivalent to 3.2 million tonnes of rare earth oxides that could be economically developed. The global total is 115 million tonnes of which half is in China.

Geoscience Australia estimates that Australia has resources equivalent to 3.2 million tonnes of rare earth oxides that could be economically developed. The global total is 115 million tonnes of which half is in China. With total world production of just 170,000 tonnes, it is obvious the problem is not the availability of resources, but rather bringing those resources profitably onstream.

Of the Australian listed hopefuls, there are four with reasonably advanced Australian projects that are actively seeking funds to implement them.

- Northern Minerals: Has an unusual deposit of “heavy” rare earths (a high atomic weight) including a high concentration of dysprosium, an element used in magnets which need to operate at high temperatures. It became Australia’s second rare earths producer last year, commissioning a A$70 million pilot plant at its holdings in the Browns Ranges in Western Australia to prove the resource and is raising funds for a separation plant. It currently ships concentrates to China for separation. It is the only non-Chinese producer of heavy rare earth oxides. A range of Chinese investors have minority stakes in the company. (Market value A$155 million)

- Hastings Technology Metals: Aiming to produce 6,700 tonnes of NdPr rich oxides by 2022 from its Yangibana deposit in Western Australia. It has non-binding offtake agreements with both Chinese and German buyers, and is targeting German finance for the A$430 million capital investment. (Market value A$140 million)

- Arafura Resources: Is seeking A$1.1 billion to finance mine and processing for NdPr rich deposit at Nolan’s Bore north of Alice Springs in the Northern Territory. The project would produce 4,400 tonnes of NdPr oxide. Although targeting non-Chinese markets, it has a non-binding offtake agreement with a Chinese permanent magnet maker. Chinese resource industry investors have a minority stake. (Market value A$72 million)

- Alkane Resources: Alkane has approvals in place to develop a zirconium and rare earth deposit near Dubbo in New South Wales and is seeking A$808 million in funding for the first stage development. It has non-binding offtake agreements for the zirconium. (Market value A$192 million)

An Australian listed company, Peak Resources has an advanced project in Tanzania while another, Greenland Minerals, is working to develop its huge Kvanefjeld deposit in Greenland. China’s Shenghe Resources has a 45 per cent stake in Greenland and a non-binding offtake for its entire output.

Well established mineral sands miner, Iluka (market value A$4.6 billion), is planning to develop a deposit of rare earth rich monazite in Victoria’s Wimmera district. Monazite is one of the most plentiful sources of rare earth, but is difficult to manage because it usually has a high content of radioactive thorium.

Australia’s share market has long supported small resource exploration companies as has Canada’s, which has a similar spread of rare earth prospects on its lists.

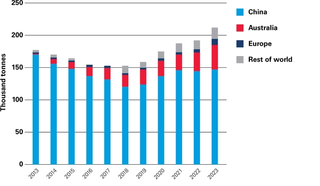

All tell the same story of demand for permanent magnets expected to surge over the next six years as the motor industry switches from petrol to electric drives while demand from wind turbine makers is expected to remain strong. The British consultancy Roskill is the main source of industry data and it expects demand for the NdPr oxides used for permanent magnets to rise by an average of 6 per cent a year between now and 2030. Roskill predicts that China will become a net importer of NdPr by the early 2020s as the enforcement of environmental guidelines brings a reduction in Chinese production. Roskill thinks there will be a big enough gap between supply and demand to lift the nominal NdPr price by 40 per cent (26 per cent real) over the next six years.

Figure 7: Global rare earth oxide production ('000 tonnes), 2013-2023

It expects new Australian projects will help to plug the gap, with total production of rare earths rising from 18,600 tonnes in 2018 (from Lynas and Northern Minerals) to a capacity of 50,100 tonnes by 2025 with production from Lynas, Northern and another two producers.22

It may happen, but it is a big jump for a company with a market value of around A$100 million to finance capital development of anywhere from A$500 million to A$1 billion. The Australian companies mentioned above have all had well defined projects for at least the last five years and are still on the launch pad, waiting for lift-off.

It can be argued that if shortages of rare earths became sufficiently acute, prices and market capitalisation of these projects would rise to a point that they could be financed. But investors would have to be satisfied that high prices, in an industry subject to booms and busts, were going to be sustained.

It is a big risk for an investor when the real operating costs of a difficult processing mill can only be guessed at and the market has frequently been oversupplied.

Of the two major projects responding to the 2010 crisis, Mountain Pass went back into Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2015 as prices slumped, while Lynas only survived because of the steadfast support of its Japanese financiers. Mountain Pass has recently been resurrected by a consortium of investors, with China’s Shenghe Minerals holding a minor non-voting 10 per cent stake. It is selling its concentrates to China for processing but is working to restart its US separation plant in 2020.

The biggest challenge for prospective producers in Australia and elsewhere is that projects are not bankable: banks will not lend to a project when the pricing is as opaque as it is with rare earths. Equity markets are similarly unprepared to deliver the capital required to bring these projects to life.

The biggest challenge for prospective producers in Australia and elsewhere is that projects are not bankable: banks will not lend to a project when the pricing is as opaque as it is with rare earths.

A Chinese metals exchange which traded rare earths collapsed amid widespread fraud in 2015. Since then, a number of research houses post public prices based on surveys of traders, mining companies and consumers, but there is no futures market or any forward pricing that could be used to secure finance. The reality is that prices are hammered out in private negotiations of long-term contracts with customers. Rare earths are not generic commodities but are mostly produced to the specification of individual customers.

There is a chicken and egg problem: potential financiers would want to see binding take-off contracts before committing, but potential customers will not commit until they are sure the project can deliver the volume and quality or purity of the material they require. Because of the technical difficulty in separating many rare earth ores, a pilot plant cannot provide that assurance — potential customers need to see the output from the full-scale plant before they are ready to sign a binding contract.

Rare earths are in many ways more like the chemical industry than mining: the heart of the business is the processing. Wesfarmers, which has a substantial chemical business, made a takeover bid for Lynas, but withdrew it after the company was only able to get a temporary extension of its operating licence in Malaysia.

Ultimately, the most likely source of finance is either from an enterprise with a big balance sheet like Wesfarmers which is making a bet on the future of batteries and electric motors and wants to get into production of the raw materials, or else it will come from a major customer which wants to secure its supplies. It would not surprise to see funding for rare earths projects emerging from the motor vehicle and energy industries, but it is not there yet. Those customers could be Chinese.

There are risks to both supply and demand. On the supply side, China may decide to develop its abundant reserves of monazite, which is not currently mined because of concerns around radioactive waste. On the demand side, technological development is unpredictable. Tesla had long preferred ‘induction’ electric motors (which use copper coils rather than permanent magnets), but recently adopted an innovative electric motor that uses much smaller amounts of rare earths than the standard permanent magnet motor and retains copper coils. Were the new Tesla design to become an industry standard, it would sharply reduce future growth for magnet materials.

Relative to more mature resource sectors such as the gold industry, the rare earths industry suffers from a series of information gaps. There is no open pricing, the cost and efficiency of a processing plant is highly uncertain with each orebody imposing unique demands and the end market use is vulnerable to unpredictable technological change.

Perhaps the biggest uncertainty facing potential developers of rare earth projects is the unpredictable actions of China, the dominant producer.

Strategic responses of Japan and the United States

The approaches of Japan and the United States to China’s dominant position in the rare earths market are an illuminating contrast, with the Japanese government much more focussed on alleviating its national economic vulnerability while the US administration’s greatest concern is ensuring self-sufficiency for its military.

Japan’s dependence on imported resources has been a dominant feature of its history, motivating its imperialism in the 1930s and 1940s, particularly following a US embargo on oil and steel shipments. Japan was also severely exposed to the 1973 OPEC oil embargo and reacted with a major government led strategy to reduce dependence on oil in favour of natural gas and nuclear power while also encouraging energy efficiency.

The approaches of Japan and the United States to China’s dominant position in the rare earths market are an illuminating contrast, with the Japanese government much more focussed on alleviating its national economic vulnerability while the US administration’s greatest concern is ensuring self-sufficiency for its military.

In 2005, as the commodities boom was just beginning to gather steam, Japan began work on a strategy to secure supplies of non-ferrous metals and in 2007, during the first administration of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry released a paper focused on rare earths. It called for the use of public funds, including overseas development assistance, to help Japanese firms acquire mining interests abroad. It also urged greater government stockpiles of critical materials. Funding for the development of non-Chinese supplies would be made available through the government-owned Japan Oil, Gas and Metals National Corporation (JOGMEC), which provides finance and guarantees as well as geological and technical support to Japanese minerals and energy companies.

In rare earths, it has worked with a trading company Sojitz to secure long-term supply agreements and joint ventures in Vietnam, Kazakhstan, India and Mongolia, as well as its most successful rare earth venture, backing Lynas. JOGMEC’s refinancing of Lynas debt this year means, as one commentator remarked, it enjoys “some of the cheapest debt in corporate Australia”.23

As a result of government interventions, non-Chinese sources now account for roughly 60 per cent of Japan’s spending on rare earths according to the UN trade database, compared with less than 20 per cent in 2010. (There are few accurate figures for a trade characterised by secrecy and smuggling.)24

The United States chose not to direct public funds to ensure an independent supply of rare earths. Its only rare earths mine at Mountain Pass has twice been mothballed because of poor profitability, although it is now back in business.

Efforts to legislate government debt guarantees for rare earth production in the wake of the 2010 crisis were unsuccessful. There is a strong view in the United States that allowing corporate failure is the process of natural selection that makes its capitalism so strong.

However, the vulnerability of the military to Chinese supplies is keenly felt and in 2017, President Donald Trump issued an executive order that the Departments of Interior and Defense should develop a strategy to reduce the country’s dependence on foreign critical minerals.

The United States has maintained a strategic stockpile of resources deemed necessary for military preparedness since the late 1930s and has, since 1973, had laws prohibiting the use of foreign specialty metals in US weapons systems although these did not refer specifically to rare earths until last year. A Reuters investigation showed that in 2012, suppliers to the F-35 strike fighter program had to obtain waivers from this legislation to include Chinese-made permanent magnets in the aircraft’s radar system and landing gear.25

A review of the Department of Defense management of rare earths by the US Government Accountability Office in 2016 found there was no systematic collection of data about what rare earths were used with knowledge confined to specialists in particular weapons systems. This meant there was no overall management of risks to supply. It was critical of the strategic stockpile, saying many of its materials were not in a useable form, with the United States lacking the commercial capability to process them.26

The response to President Trump’s executive order, a strategy to “ensure secure and reliable supplies of critical minerals” published by the Department of Commerce in June, highlighted the fact that the erosion of United States manufacturing capability is as much of an issue as the lack of a secure supply of raw materials. “Increasing mining without increasing processing and manufacturing capabilities simply moves the source of economic and national security risk down the supply chain and creates dependence on foreign sources for these capabilities,” it said.27

The report included several concrete recommendations, such as improving the funding for the strategic stockpile, streamlining mining approvals, easing land access requirements and improving collaboration between the US Geological Survey and its peers in allied countries, particularly Canada and Australia.

It also highlighted the need for greater federal support for research and development in rare earths and downstream products and for stimulating private sector investment in production capacity. In both these cases, however, it did not articulate strategies but rather suggested they should be developed.

It said options to support the private sector included investment tax credits, capital gains tax exemptions, low interest loans and guarantees, workforce training support, trade assistance and policies for domestic sourcing and small business procurement.

President Trump has taken a significant step to stimulate investment in rare earths processing by invoking the Defense Production Act, which empowers the Department of Defense to provide financial assistance to ensure critical supplies are available.

President Trump has taken a significant step to stimulate investment in rare earths processing by invoking the Defense Production Act, which empowers the Department of Defense to provide financial assistance to ensure critical supplies are available. It also gives the government the power to order private companies to meet the needs of defence-related contracts before they satisfy their commercial demand.

His declaration says that in the absence of government intervention, US industry cannot reasonably be expected to provide production capability for separating light or heavy rare earths, or manufacturing rare earth magnets.

The act was devised in 1950 to ensure the military was adequately supplied during the Korean war and the Cold War. It enables the Department of Defense to make loans or offer loan guarantees, with or without interest.

Generally, the amounts involved are not large — congressional approval is required for advances of more than US$50 million. Larger sums can be advanced with a presidential waiver and congressional approval for defence projects is rarely a problem. In practice most loans and guarantees offered under the scheme have been below the US$50 million threshold. The Department of Defense will not take overall project financing responsibility. The intent is that access to early stage funding may help companies in reaching their investment decision. It is still assumed that projects would have offtake agreements lined up and would be essentially commercial in their nature.

The most prospective direct Australian response to US defence needs is a plan by Lynas to establish a heavy rare earths separation plant in Texas, in joint venture with US chemicals business Blue Line Corporation. The cost and funding of the plant has not been disclosed, with Lynas suggesting it will be funded from internal resources. It would likely qualify for assistance under the Defense Production Act. Lynas chief executive Amanda Lacase highlights that there is no significant capacity to separate heavy raw earths outside China. Lynas has a very clear market positioning as a non-Chinese supplier with no major Chinese shareholding. This makes it attractive to US rare earths users. Lacase cautions it can take many years to progress from investment commitment to first production.

In the United States, MP Materials’ profitability has been hit by the imposition of 30 per cent tariffs on its exports of concentrates to China in retaliation for US tariffs. The company is working on a US$200 million plan to reopen its mothballed separation plant next year to give the United States its own refining capacity, and bringing competition to Lynas for non-Chinese markets. The tariff war may cause delays to the project.

The United States has been discussing broader opportunities for cooperation and collaboration with Australia to promote the development of non-Chinese sources of rare earths. Following discussions between President Trump and the then prime minister, Malcolm Turnbull, in February 2018, shortly after the US president’s executive order, an interdepartmental taskforce was established under Prime Minister and Cabinet to explore options.

There are some obvious opportunities, such as a collaboration between Geoscience Australia and the US Geological Survey which has been underway since July last year with a formal letter of intent concluded last December. The US strategy document noted that less than 5 per cent of the United States had regional aeromagnetic data sets, and contrasted this with Australia and Canada, where the provision of comprehensive geophysical data as a public good had fostered the development of mineral resources. The CSIRO’s mineral resources division also gives Australia a unique capability for government-led research and development. It has been working on improving rare earth processing methods which remains very energy and resource intensive.

There are as yet no obvious channels for the US interest in improving the resilience of its critical materials supply chain to support the development of new Australian rare earth projects, which need offtake agreements and base funding to build mines and processing plants.

However, there are as yet no obvious channels for the US interest in improving the resilience of its critical materials supply chain to support the development of new Australian rare earth projects, which need offtake agreements and base funding to build mines and processing plants. Both Arafura and Alkane visited the US Defense Department during a trade mission in February without securing commitments.

Part of the problem is that the Department of Defense needs are small, amounting to only 1 per cent of US demand overall, according to the GAO report. The use of rare earths by suppliers to the Department of Defense is very fragmented, so it does not have the obvious customers with demand of sufficient scale to under-write new projects.

In the absence of financial incentives for domestic sourcing, US industry has continued purchasing from China. According to the UNCOM database, the United States directed 54 per cent of its spending on rare earths imports to China in 2017, down from 65 per cent in 2010.

Although the cost of insuring against supply disruption has been too high to support the development in the United States of a parallel rare earths industry to that in China, there has been some movement, as shown by the revival of the Mountain Pass mine. The proposed joint venture between Lynas and Blue Line for a heavy rare earth plant shows that if there is a large enough gap in the US market, someone will fill it. In a similar manner, there was a period where there was no US capacity for manufacturing rare earth magnets after the major manufacturer was bought by a Chinese consortium and its plant relocated to China. However, several US magnet manufacturers have since moved into that market, although the majority of supplies are still imported, mainly from China.

Australia’s interests as a producer

As a producer rather than a consumer of rare earths, Australia’s national interest is in the development of its resources ahead of those in other prospective countries. Of the several dozen rare earth projects around the world, no more than four or five would have a prospect of being funded over the next five years.

Although Australia’s alliance with the United States means it understands the US drive to develop critical mineral supplies independent of China, Australia is not opposed to Chinese involvement in developing Australian projects. For example, a Chinese state-owned enterprise has long been a minority shareholder in Arafura.* Chinese investors have also been important in the development of Northern Minerals.

The specialist critical minerals consultancy Roskill expects China will require the development of Australian rare earth resources to meet the growing demand from its rare earths manufacturing industry. It is China that would be taking the risk with these investments, not Australia, as its assets could face expropriation and export controls in any conflict.

The Foreign Investment Review Board recommended against allowing a full Chinese takeover of Lynas in 2009, but would have been prepared to allow the purchase of 49 per cent with a minority of board seats. Although the Foreign Investment Review Board assesses each foreign investment on its merits, it would likely take a similar position to future acquisitions, bearing in mind that China is a deep source of expertise in rare earths processing and marketing. Under the 2015 China-Australia Free Trade Agreement, private Chinese companies can make investments of up to A$1 billion without Foreign Investment Review Board approval.

Australia’s national interest is to have its rare earth projects developed ahead of competitors, and the best contribution government can make to foster commercial development is to ensure that infrastructure costs are as low as possible and environmental and other approvals are speedy.

Australia released a Critical Minerals Strategy in early 2019. It emphasises the government’s role in investment promotion and supporting research and development.

Geoscience Australia has sought to define Australia’s potential in critical resources, while it has received A$100 million in funding to conduct high-resolution geoscience mapping. The government also funds a Cooperative Research Centres on mineral exploration and battery technology.

Austrade has helped to introduce companies to potential sources of finance by funding roadshows. The Northern Australia Infrastructure Facility has been considering applications from both Arafura Resources and Hastings Technology for loans to finance infrastructure associated with their developments. However, this funding, which is only available for projects in the north of Australia and is only supplementary, assuming that the project has a base of its own finance.

The strategy also incorporates the Commonwealth’s Major Projects Facilitation Agency, a body that assists projects to gain regulatory approvals. Resource developers say the agency makes a huge difference to the ease of navigating the regulatory hurdles.

Much like the United States, Australia has difficulty in crafting programs specifically for a sector like rare earths, even if it believed there were elements of market failure in the failure to develop established resources.

One of the most innovative rare earth developers, Northern Minerals, was financially stretched by a decision of the Department of Industry to reject its application for research and development grants. The decision that it did not qualify for the R&D grant came after it had already received A$13.4 million, which it was required to repay to the tax office, and also meant it did not receive A$10.8 million it was counting on. For a start-up company, these were large sums. Although the Australian Taxation Office extended the deadline to make the repayment, it had borrowings secured against the R&D grants, which it had to refinance rapidly. The decision was over whether its pilot plant qualified as research and development, with the department concluding that it was a business production asset. Northern was among a number of small resource companies which had claims for R&D grants rejected.

Northern is appealing the finding, with its chief executive George Bauk arguing that the firm’s rare earth processing plant is still at an experimental stage. Although it is producing the high-value rare earth oxide dysprosium, he cannot yet say what his operating costs are, because the processes have not yet stabilised.

The R&D support scheme has been overhauled since Northern made its applications, and under the current scheme, firms with sales of under A$20 million can claim a maximum of only A$4 million, which greatly limits the use of the scheme by junior resource companies, although they are a highly innovative sector of the Australian economy. The level of revenue is a poor guide to the potential proceeds from innovation, which the scheme is intended to promote.

If a decision were made on national security grounds that the Australian government should provide financial support for the development of rare earth or other critical mineral resources, it would have to confront the biggest hurdle for rare earth developers, which is the difficulty in obtaining their base funding.

If a decision were made on national security grounds that the Australian government should provide financial support for the development of rare earth or other critical mineral resources, it would have to confront the biggest hurdle for rare earth developers, which is the difficulty in obtaining their base funding. Financial guarantees for project development, such as those provided by the Japanese for Lynas, would be a big step for the Australian or US governments.

The government’s critical minerals strategy made mention of the potential to use its export finance agency to support the expansion of resource projects to meet international demand, within WTO guidelines. Export Finance Australia includes a ‘national interest account’, under which the trade minister can direct it to extend loans or offer guarantees in support of an export business. Any losses from such transactions are borne by the Commonwealth, not by Export Finance Australia (formerly known as the Export Finance and Insurance Corporation). The government used that account in 2018 to support its defence equipment export strategy with a total facility of A$3.8 billion. It could be used to support sales to US customers, although there is no precedent for it providing the development finance for a start-up project.

The environmental problem

Most mining poses challenges to environmental management in the extraction and the processing. It can be profitable to extract gold at a grade of only 1 or 2 grams per tonne of ore, but it uses 250 litres of cyanide-enriched water for every gram. Rare earths are more complicated than most minerals, because they usually bound together in compound rocks with different forms of mineralisation. Processing requires numerous steps consuming water, acid, electricity and heat. A study of China’s Bayan Obo mine found it used 38,000 litres of water and 180 megajoules of energy (equivalent to raising 400 litres of water from freezing to boiling temperature) to produce one kilogram of refined rare earth oxide.28 And then there is the waste. The Bayan Obo tailings dam is about 9 kilometres in diameter and is composed of acidic and moderately radioactive materials. Having been inadequately sealed, the dam is leaching into the ground water and is a threat to the headwaters of the Yellow River.

The environmental problems are worse at the sites of the illegal rare earth mines in the south of China, where acid is poured directly into trenches to dissolve the rare earths in clay which is then taken away to be processed. Illegal strip mining in Southern China generates 2,000 tonnes of tailings, 1,000 tonnes of wastewater containing heavy metals and 300 square metres of ground cleared for every tonne of rare earth oxide.29 Illegally-produced oxides are frequently smuggled into Vietnam and Myanmar and then reimported to China as ‘clean’ material for further processing.

The Chinese authorities have been making more determined efforts to shut illegal operators down and to improve the environmental performance at the Bayan Obo and other legal rare earth operations. China has barred rare earth imports from Myanmar in a bid to stop it being used to ‘launder’ illegal Chinese production and is trying to get ‘traceability’ certification accepted for rare earths.

Xi Jinping, who made combatting pollution one of the three “tough battles”, alongside alleviating poverty and reducing financial risks, wants China to reject the economic model where lax environmental protection is seen as an acceptable price for development.

Rare earths producers outside China must also contend with the difficult environmental consequences. Lynas was encouraged to establish its US$800 million processing plant in Malaysia by generous investment incentives. The company has always denied that it expected easier treatment of environmental issues than in Australia. However, there was a bad history with rare earths in Malaysia, with a prolonged and ultimately successful community battle in the 1980s and 1990s against the waste dump of a rare earths company in which Mitsubishi Chemical Industries was the major shareholder. International experts found excessive levels of radiation and unsafe storage.

The activists involved in that battle believed Lynas would repeat this history, particularly after a New York Times report in 2011 of leaked emails from Lynas engineers concerned sub-standard steel was being used in the plant. Following the unexpected overthrow of the long-established UMNO government of Najib Razak in 2018, there was a widespread expectation that Lynas would be forced to close its processing plant, particularly when long-standing opponents of the plant, Fuziah Salleh and Yeo Bee Yin were appointed deputy minister in the Prime Minister’s department and environment minister respectively. Lynas chief executive Amanda Lacaze has acknowledged that most of the opposition to the Malaysian plant has come from members of Malaysia’s Chinese community but says she cannot say whether that is related to China’s desire to regain its market monopoly, noting simply that the geopolitical importance of Lynas gives her confidence that a good outcome will be reached.30

Lynas argues that its waste is no more radioactive than imported phosphate fertilisers. Reviews commissioned by the Malaysian government have confirmed it meets guidelines, however opposition continues. The company was given a highly conditional six-month extension to its operating licence in September, after Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad voiced concern that Malaysia’s reputation for foreign direct investment would suffer if the plant were forced to close. Lynas has to come up with a means of permanent storage for mildly radioactive waste it has already produced in Malaysia, identify a location for it, and win the approval of the state government. It has also agreed to build a plant in Western Australia to remove most of the radioactive materials before minerals are sent to Malaysia for further processing.

Closure would have returned China’s share of global production to around 90 per cent. The Malaysian government would doubtless have been made aware of the strategic concern of the Japanese and Australian governments over the decision.

* An earlier version of this report incorrectly identified Shenghe Resources as a shareholder in Arafura.