Executive summary

Subdued wages growth has been a feature of the Australian and US economies in recent years, posting the slowest growth on record on some measures. This has led some to question whether workers are sharing in the benefits of increased productivity and greater economic prosperity.

The United States has seen a long-running debate over the supposed ‘decoupling’ of wages from productivity and its implications for the labour share of income and income inequality. There is an extensive US literature on ‘decoupling,’ with evidence presented both for and against this phenomenon.

It is important to distinguish between the earnings of the average and the median (sometimes called ‘typical’) worker. Economy-wide productivity growth is mostly expected to raise average rather than median earnings.

This report finds the link between productivity and compensation in Australia remains robust under existing institutional arrangements, although this does not preclude the possibility of further reforms that could boost productivity, worker compensation and improve the distribution of productivity gains.

The literature supporting the ‘decoupling’ thesis based on median earnings confuses the productivity-compensation nexus with distributional issues. This confusion can lead policymakers to neglect policies focused on productivity growth and focus too much on redistribution.

This report finds the link between productivity and compensation in Australia remains robust under existing institutional arrangements, although this does not preclude the possibility of further reforms that could boost productivity, worker compensation and improve the distribution of productivity gains.

The long-run increase in the capital share in the United States, other G7 economies and Australia is largely driven by the housing component of the capital share. This in turn reflects the increased scarcity of housing driven by excessive regulation of land use and dwelling construction. Policymakers concerned about income inequality should focus on improving housing supply rather than workers’ bargaining power.

This report also shows that the cyclical variation in the labour share is a consequence of the relatively greater volatility of the capital share and not changes in workers’ bargaining power.

Monetary policy can also play a role in improving nominal wages growth by returning inflation to the central tendency of the Reserve Bank’s inflation target.

Introduction

Subdued wages growth has been a feature of the Australian and US economies in recent years, posting the slowest growth on record on some measures. Real wages should be closely linked to productivity and nominal wages to productivity and inflation. Inflation and productivity growth have also slowed relative to previous decades and this accounts for some of the observed weakness in wages.

But slow wages growth has still led some to question whether workers are sharing in the benefits of increased productivity and greater economic prosperity. If wages do not keep pace with productivity growth, then the labour share of income will decline over time relative to the capital share. A declining labour and rising capital share of income is also a stylised fact for many advanced economies in recent years.

The view that the link between productivity and wages is broken has been the basis for a number of public policy recommendations, including suggestions Australia should return to some form of national wages policy or centralised wage fixing and that the Superannuation Guarantee contribution rate should be increased. The Reserve Bank has also blamed the undershooting of its inflation target on slow wages growth.

The United States has seen a similar and longer running debate over the supposed ‘decoupling’ of wages from productivity and its implications for the labour share of income and income inequality. This debate has informed populist politics on both the left and the right. There is extensive US literature on ‘decoupling’, with evidence presented both for and against this phenomenon.

The US debate points to a key distinction that needs to be made to avoid confusion about these issues and to draw the right policy conclusions. It is important to distinguish between the earnings of the average and the median (sometimes called ‘typical’) worker. Median measures of compensation are more representative of the typical worker in capturing the middle of the income distribution. Average wages growth may be higher than median wages growth if there is stronger growth at the top end of the earnings distribution relative to the middle of the distribution. The average/median ratio can be viewed as a measure of wage and income inequality.

Economy-wide productivity growth is mostly expected to raise average rather than median earnings. The link between productivity and average compensation does not guarantee that productivity and income growth will be equally distributed. Much of the US literature on ‘decoupling’ between productivity and compensation references median rather than average earnings to argue that the ‘typical’ worker does not benefit from productivity growth.1 But this is the wrong measure to use when examining the productivity-compensation nexus.

The literature supporting the ‘decoupling’ thesis based on median earnings confuses the productivity-compensation nexus with distributional issues, whereas these should be viewed as distinct, albeit related, questions. A robust compensation-productivity nexus does not preclude problems with the distribution of productivity gains and growing income inequality, as the US literature arguing against the ‘decoupling’ thesis readily acknowledges.2

Both sides of the debate recognise that productivity growth is a necessary but not sufficient condition for improving wages growth for all workers. The danger in confusing the productivity-compensation nexus with distributional issues is that it can lead policymakers to neglect policies focused on productivity growth and focus too much on redistribution. In particular, it may lead policymakers to move away from competitive wage determination on the basis that it is not delivering for workers. But as Australia’s historical experience with non-market approaches to wage setting before the early 1990s demonstrates, this is likely to lower productivity, as well as break the productivity-compensation nexus, to the detriment of growth in incomes.

This report examines the relationship between productivity and compensation in Australia and the United States. In particular, it replicates work by former US Treasury Secretary Larry Summers and Anna Stansbury on the productivity and compensation link using Australian data. Consistent with Stansbury and Summers, I find that the link between productivity and compensation in Australia remains robust under existing institutional arrangements, although this does not preclude the possibility of further reforms that could boost productivity, worker compensation and improve the distribution of productivity gains. While Stansbury and Summers also examine the ratio of average to median compensation, Australia lacks adequate data on median hourly compensation that would permit a similar analysis.

The evidence for Australia suggests that the evolution of labour market policies from centralised wage fixing to more flexible enterprise bargaining arrangements is still serving Australia well in ensuring that wages growth is closely tied to productivity growth.

The US debate has also focused on the declining labour share of income relative to capital as a measure of both the productivity-compensation nexus and income inequality. The declining labour share has been interpreted as evidence of a decline in the bargaining power of workers. In fact, the long-run increase in the capital share in the United States, other G7 economies and Australia is largely driven by the housing component of the capital share. This in turn reflects the increased scarcity of housing driven by excessive regulation of land use and dwelling construction. Policymakers concerned about income inequality should focus on the issue of housing supply rather than workers’ bargaining power. I also show that the cyclical variation in the labour share is a consequence of the relatively greater volatility of the capital share and not changes in workers’ bargaining power.

I also follow Stansbury and Summers in testing whether technological change is driving the decline in the labour share of income in Australia. Consistent with their results for the United States, I find no long-run relationship between productivity growth and the labour share of income. When labour productivity is decomposed into contributions from capital intensity and multifactor productivity, it is capital intensity that has the greater explanatory power for the labour share of income. This reflects the increased capital intensity of the Australian economy following the terms of trade and mining investment boom.

Low inflation and low inflation expectations in Australia and the United States have also weighed on nominal wages in both countries, with inflation running below the Reserve Bank’s 2-3 per cent target range for an extended period.3 I show that nominal gross domestic product (GDP) largely explains nominal wages in aggregate. Nominal GDP is in turn fully determined by monetary policy in the medium- to long-run. Monetary policy can accordingly play a role in restoring nominal wages growth by returning inflation to target.

The evidence for Australia suggests that the evolution of labour market policies from centralised wage fixing to more flexible enterprise bargaining arrangements is still serving Australia well in ensuring that wages growth is closely tied to productivity growth. Raising productivity growth is still the best way to improve average workers’ incomes.

The Australian debate

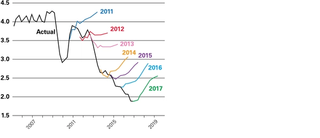

Concerns about the strength of wages and its relationship to productivity growth have been voiced by a number of policymakers, those in the trade union movement, academia and others. The debate reflects persistent downside ‘surprises’ to nominal wages growth relative to official and private sector forecasts. Figure 1, from Bishop and Cassidy,4 shows the evolution of the wage price index relative to the Reserve Bank’s expectations in its February Statements on Monetary Policy.

Figure 1: Wage price index forecasts (%), year-ended*

These persistent forecasting errors imply the Reserve Bank (RBA) is operating with a flawed model of wage determination. The RBA is not alone in this. A similar bias is evident in the forecasts of Treasury and the private sector. The RBA views wages as one of the main determinants of inflation.5

The most recent realisation of the wage price index was a growth rate of 2.3 per cent for the year-ended December 2018. Inflation over the same period was 1.8 per cent, implying subdued real wages growth of 0.5 per cent. Subdued wages growth has been broad-based across different industries, states and territories, job levels and between the public and private sector,6 with declining levels of wage growth dispersion.7 This points to economy-wide, rather than sector-specific or microeconomic, factors as the main explanation. It is noteworthy that measures of the dispersion of labour productivity growth across industries has also declined.8

Reserve Bank Governor Philip Lowe has called for a return “to a world where wage increases started with a three rather than a two”. He argues that low wages growth is contributing to low rates of inflation, raising real debt burdens and “diminishing our sense of shared prosperity”.9 Central banks around the world have been puzzled by the failure of wages growth and inflation to accelerate as labour markets have tightened again in the wake of the financial crisis.10

Former Prime Minister Paul Keating also addressed the relationship between wages and productivity in 2018:

“But something more troubling is afoot than a short run mismatch between the growth in nominal wages and the growth in the underlying productive capacity of the economy. What is concerning many people is the possibility that one of the key drivers of a market economy — the link between real wages growth and the growth in labour productivity — may have lost its magic. Simply put, wages growth is only keeping pace with inflation. This means that wage earners are failing to benefit from the growth in labour productivity.”11

Keating raised the question:

“Are we living in a new world where the structure of the economy has changed, where the bargaining position of workers has declined — and declined to such an extent, that they can no longer secure the benefits of their own productivity? Or are we heading back to a world where, of necessity, productivity growth will need to be delivered centrally?”

Apart from raising the spectre of a return to centralised wage fixing, Keating’s observations on the relationship between wages and productivity were intended to support his perennial call for a greater percentage of workers’ wages to be diverted to superannuation through a higher Superannuation Guarantee defined contribution rate. In Keating’s view, increased superannuation would force employers to hand productivity gains back to workers. This ignores the reality that the burden of superannuation contributions falls on workers through reduced take-home pay and not employers. Compulsory contributions reduce competition in superannuation, leading to excessive asset management fees. Superannuation is also more heavily taxed than some competing asset classes, most notably housing.12 Keating’s policy prescription would directly weaken worker compensation exclusive of superannuation benefits.

Labor Party Assistant Treasurer Andrew Leigh wrote in The New York Times under the heading ‘The End of the Australian Miracle?’:

“Stagnant wages for average workers could reflect poor productivity. But that isn’t true here [in Australia], with productivity growing at a healthy rate. A bigger problem for employees is that they have less bargaining power.”13

In light of recent weakness in wages growth, some in the trade union movement now view the move away from centralised wage fixing to enterprise bargaining as a mistake. According to Tim Lyons, a former assistant secretary of the Australian Council of Trade Unions:

“I’m increasingly of the view that we need to describe firm-level enterprise bargaining as a failure. If I’d been there at the time, at the ACTU, I probably would have made roughly the same decisions that were made, but in retrospect, we overshot the mark. Going from complete centralised wage fixing all the way back to firm-level bargaining was really a recipe for very poor outcomes.”14

Yet centralised wage fixing, at least under the Labor Party-ACTU Accord in the 1980s, was designed explicitly to suppress wages growth and eliminate a real wages ‘overhang’ in exchange for improvements in the ‘social wage’.15

Even some financial market economists have called for a return to some form of wages policy. According to the Commonwealth Bank’s chief economist, Michael Blythe:

“Given the usual economic fundamentals, like the unemployment rate, you would be expecting to see wages growth faster than it is right now. There’s a market failure here, in a way, and governments are there to sort out market failures. We used to talk about wages policy. I think maybe the time has come again to think about that.”16

Some academics have also pointed to a decline in trade union power as a factor behind weak wages growth. According to Emeritus Professor Joe Isaac:

“…an important explanation is to be found in the change in the balance of power in the labour market in favour of employers and against workers and unions… the institutions that have in the past driven wages to take up productivity advances, have lost much of their capacity to influence wages…To restore the institutional mechanism for wages growth, a return to some of our earlier industrial relations law may be called for.”17

Isaac argues that “this conclusion is based on the association over time of union power decline and slow wages growth, [and] it seems reasonable to claim, at least prima facie, a causal connection between them”.

In 2013, the Australian Council of Trade Unions released an analysis arguing there had been a decoupling of labour income and productivity, noting that this will “result in higher income inequality”.18

With such a broad spectrum of opinion suggesting that some of Australia’s most fundamental economic institutions are not delivering for workers, it is important that these claims are put to the test.

The US debate

The United States has also seen a debate about the causes and implications of weak wages growth. The US debate has been running for longer than that in Australia and pre-dates the financial crisis of 2008.

Dean Baker summarised a widely held view when he said in 2007 that “most workers have seen relatively little benefit from the economy’s growth over the last three decades”.19 One commonly cited stylised fact is that average hourly wages adjusted for consumer price inflation have not increased since the 1970s.20 This is true enough as conventionally measured, but this report shows why this measure is misleading.

The debate over the productivity-compensation nexus has fed into a wider debate about income inequality, which has been a more salient issue in the United States than Australia. According to William Galston, writing in the Wall Street Journal:

"In the past two decades there has been a sharp drop in the share of national income going to working- and middle-class Americans. As the discontent among these workers begins to affect their livelihoods and the entire nation’s politics, policymakers must either hope the market will somehow fix wage stagnation or enact policies to reverse it."21

Harold Meyerson, the editor of The American Prospect, says that “today, for the vast majority of American workers, the link between their productivity and their compensation no longer exists”.22 This leads Meyerson to recommend changes to minimum wages and corporate taxes designed to transfer income from capital to labour.

One commonly cited stylised fact is that average hourly wages adjusted for consumer price inflation have not increased since the 1970s. This is true enough as conventionally measured, but this report shows why this measure is misleading.

According to the Economic Policy Institute, raising Americans’ pay is “our central economic policy challenge”.23 But the EPI’s researchers have little confidence in the ability of increased productivity growth to meet this challenge:

"…although boosting productivity growth is an important long-run goal, this will not lead to broad-based wage gains unless we pursue policies that reconnect productivity growth and the pay of the vast majority."24

Yet as other economists note, slow wages growth is not necessarily a surprise given low inflation and productivity growth relative to earlier decades. According to the former chair of President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers, Jason Furman:

“This is simply what a high-pressure economy looks like when productivity growth rates and inflation are both relatively low. Some of the other explanations — including inequality, an especially popular answer these days — appear to point in the wrong direction. For instance, despite what you may have heard, economists broadly accept that in the past few years, wage growth has actually been stronger at the bottom than at the top…

“The wage puzzle is not particularly puzzling when you think about what determines wage growth. The policy solutions are even less of a mystery. We may not have the solution for magically improving productivity. But there’s a lot we can do to continue to increase wages for all workers.”25

According to Furman, it is weak inflation that is the larger puzzle, although he correctly implicates the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy as the main driver of low inflation outcomes.

What does US research tell us about the productivity-compensation link?

US research points to a number of important methodological considerations that need to be taken into account when evaluating the relationship between productivity and worker compensation. The introduction to this report has already mentioned the important distinction between the average and median worker. There are other factors that need to be considered in ensuring that both productivity and compensation are being measured correctly.

Adjusting for inflation

Many of the figures in relation to real wages cited by participants in the Australian and US debate are based on adjusting wages growth for consumer price inflation as measured by the consumer price index. This is a relevant adjustment if the aim is to measure the purchasing power of workers’ wages. But it is the wrong measure to use in evaluating the link between workers’ compensation and productivity. Employees are compensated on the basis of the value of the goods and services they produce and not on the basis of what they consume. The consumer price index includes the cost of goods such as imports that domestic workers do not produce.

As Martin Feldstein notes “basic theory reminds us that real compensation should be measured using the same price index that is used to calculate productivity. When this is done, the rise in [US] compensation has been very similar to the rise in productivity”.26 Robert Lawrence finds similarly.27 This adjustment is particularly important at the industry level for high productivity, high-tech industries in the United States, where output prices have fallen over time in contrast to the increase in consumer prices. In Australia, the terms of trade boom drove a wedge between producer and consumer prices that yields very different results when adjusting wages for inflation. Compensation deflated by the GDP deflator (the real producer wage) in Australia tracks labour productivity more closely than compensation deflation by the consumption deflator (the real consumer wage).

Compensation is more than just wages

Total compensation is typically greater than ordinary time wages and the non-wage share of total compensation has been growing over time in the United States and Australia. These non-wage employee benefits are often paid in lieu of wages, as employers must still bear the cost of these benefits. Non-wage compensation can include paid leave, health insurance, supplemental pay and bonuses and retirement benefits. According to the US Council of Economic Advisers, ignoring non-wage compensation understates growth in total compensation per hour worked by 0.2 percentage points in recent years, both by understating the numerator and exaggerating the denominator.28 In the United States, health insurance benefits are an important source of non-wage compensation for many workers. In Australia, the Superannuation Guarantee (SG) sees 9.5 per cent of wages and salaries diverted into superannuation funds at the expense of take-home pay. The SG rate has been increasing over time and is legislated to increase further.

Lags are important

The expected one-for-one relationship between growth in real compensation and productivity does not necessarily hold in the short-run, only the long-run.29 For any given period, compensation growth may be faster or slower than productivity growth. The lag could operate in both directions. It would not be surprising for changes in compensation to lag changes in productivity as nominal wage contracts lag changes in output per worker. However, to the extent that firms and workers anticipate future productivity gains, changes in compensation might also lead productivity. Subtracting the current inflation rate from current wages growth and comparing to productivity growth over the same period (as Paul Keating does in his op-ed cited previously) may give a misleading picture.

In the US context, Feldstein notes that allowing for lags of up to two years strengthens the statistical relationship between compensation and productivity.30 Similarly, Stansbury and Summers find that using longer moving averages of the data strengthens the statistical association between compensation and productivity.31 In modelling the Australian data, this report allows for considerable flexibility in fitting lags to these relationships.

US studies

When these and other methodological considerations are taken into account, the gap between productivity and compensation in the United States largely disappears. Two major studies exemplify the anti-‘decoupling’ literature.

The Robert Lawrence study

Robert Lawrence decomposes the supposed productivity-worker compensation gap in the United States based on these and other methodological considerations and finds that:

“Between 1970 and 2001 properly measured, there was no difference between the growth of real output per full-time equivalent worker and the growth in real (product) compensation paid to workers. This also implies there was no increase in the share of income going to profits over these three decades.”32

The picture since 2000 is more mixed and the gap widened in the wake of the 2008-09 recession, but by far less than suggested by measures that fail to take the above methodological considerations into account.

The Stansbury-Summers study

Anna Stansbury and Larry Summers (Stansbury and Summers) investigate the productivity-compensation link, exploiting “the natural quasi-experiment provided by the fact that productivity growth fluctuates through time”.33 They seek to explain both average and median measures of real wages with reference to economy-wide productivity, while controlling for spare capacity in the labour market as measured by the change in the unemployment rate. They find that median and average compensation growth increases by between 0.7 and 1.0 per cent for a one per cent increase in productivity growth between 1973 and 2016. The elasticity tends to be larger the longer the moving average applied to the data, implying that lags are an important factor in this relationship. It should be noted the authors use a consumer price deflator to measure real wages and wages not total compensation to measure employee benefits. They note that this introduces a downward bias to their estimates of the relationship between compensation and productivity.

Stansbury and Summers also model the labour share of income to test whether the labour share falls more quickly in periods when labour productivity growth is more rapid. The mean/median compensation ratio (a proxy for income inequality) is also tested to see whether it rises faster in periods of faster productivity growth. Productivity growth can be viewed as a proxy for technological change and its effect on wages. They find no apparent relationship between changes in the rate of productivity growth and changes in the labour share before 2000, although the results are more mixed for the period since. There is no significant relationship between productivity growth and changes in the mean/median compensation ratio. Overall, Stansbury and Summers conclude that “other factors orthogonal to productivity have been acting to suppress compensation even as productivity growth has been acting to raise it”.

The US evidence suggests that the long-run relationship between productivity and compensation still holds and does not explain changes in the labour share of income. There is evidence of a weaker relationship between productivity and compensation in the period since 2000, but the relationship has not disappeared altogether as some have claimed.

Replicating Stansbury-Summers with Australian data

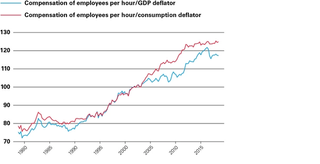

The relationship between labour productivity and wages in Australia is shown in the following charts. Figure 2 shows the consumer and producer wage indexed to March 2003, coincident with the onset of the terms of trade boom.

Figure 2: Consumer and producer wage, March quarter 2003 = 100

The terms of trade boom drove a wedge between the consumer and producer wage, which has narrowed more recently as the boom has moderated. The consumer wage shows a flatter trend after the terms of trade boom peaked, consistent with recent weakness in wages growth. The producer wage also shows weakness more recently.

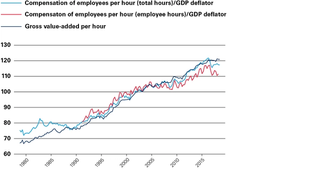

Figure 3 compares labour productivity measured by gross value-added per hour worked and two measures of the producer wage based on different measures of hours worked. One measure is for total hours worked by employed persons, the other is hours worked by employees, which has a closer, although not perfect, alignment with compensation of employees.34 Treasury and the Reserve Bank typically reference the former hours worked series on the basis that the differences in coverage are not material for most purposes and to ensure that their measures of hourly wages are based on publicly available sources rather than less transparent internally derived measures.

Figure 3: Labour productivity and the producer wage, March quarter 2003 = 100

The two measures of the producer wage have a close relationship with labour productivity for much of the sample period for which they are available, although compensation lags productivity growth more recently. The weakness is more pronounced and more persistent based on the employee measure rather than the employed persons measure of hours worked. Both measures are consistent with the observation that real wages have somewhat lagged productivity in recent years. Note the real wage ‘overhang’ in the early 1980s that was corrected through weaker real wages growth under the Accord in the mid- to late- 1980s. The shift to enterprise bargaining from the early 1990s was associated with a stronger relationship between productivity and compensation, at least until recently.

Modelling the compensation and productivity relationship

The relationship between the data shown in Figure 3 can be modelled more formally to test whether there is a long-run relationship between productivity and compensation and better quantify the relationship. I model the relationship between the producer wage and productivity in Australia, controlling for labour underutilisation as a proxy for spare capacity in the economy and workers’ bargaining power. I also subsequently model the effect of productivity growth on the labour share of income. The Australian Bureau of Statistics does not produce a sufficiently long or high frequency time series on median earnings to allow the modelling of the median/mean compensation ratio. The median earnings series is also not sufficiently inclusive of non-wage benefits.

The modelling framework is specified in Appendix 1.35 It is well-suited to estimating long-run relationships between the level of real compensation and productivity in the presence of lags. It allows the data to determine the dynamic relationship between compensation and productivity by searching across all possible models with lags up to an arbitrary length (eight quarters or two years in this case) and then choosing the model with the best fit. The model is thus theoretically agnostic about the nature of the dynamic relationship between productivity and compensation. Although somewhat different to the methodology reported in Stansbury-Summers, they note that the approach used here produced similar results to those reported in their paper. My approach is more flexible in incorporating lags, allows for direct estimation of long-run relationships and improves on Stansbury and Summers by employing a measure of total compensation and using the GDP deflator for inflation adjustment.

The first model seeks to explain the producer wage (compensation of employees (COE) per hour worked by employed persons and adjusted for inflation by the GDP deflator). COE is the most inclusive measure of employee compensation, including superannuation benefits, although is susceptible to effects from changes in the composition of the workforce. Note that this measure does not capture employee compensation for unincorporated enterprises. Cowgill constructs a measure of labour income including the unincorporated sector that shows greater decoupling between labour income and productivity between 2000 and 2011 than shown in Figure 3.36

Three sample periods are considered. A full sample from Q3 1978 to Q3 2018, with the start of the sample period determined by the availability of data on aggregate compensation and the lag structure of the model. A second sample from Q1 1992 to Q3 2018 seeks to capture the period since the introduction of enterprise bargaining in Australia.37 The third sample seeks to capture the period since Q1 2000, a period for which both the US and Australian literature finds greater evidence of decoupling.

Table 1 reports the estimated long-run response of the producer wage to gross value added per hour worked by employed persons and the labour underutilisation rate, as well as the quarterly speed of adjustment to the deviation from the long-run relationship.

Table 1: Long-run response of producer wage (based on total hours) to labour productivity

|

|

Full sample |

Pre-ent. barg. |

Post-ent. barg. |

Post-2000 |

|

Productivity |

0.87*** |

0.01 |

0.92*** |

0.89*** |

|

Underutilisation |

-0.05 |

0.11 |

0.03 |

0.06 |

|

Speed of adjustment |

-0.16 |

-0.38 |

-0.28 |

-0.28 |

|

F-bounds test stat. |

6.05** |

2.08 |

5.72** |

4.43* |

|

t-bounds test stat |

-4.15*** |

-1.96 |

-4.14*** |

3.63** |

A one per cent increase in productivity raises the producer wage by around 0.9 per cent for the full sample period and the period since the introduction of enterprise bargaining. There is no evidence to support a weaker relationship between productivity and earnings in the period since the introduction of enterprise bargaining. The test statistics indicate that these are statistically significant long-run equilibrium relationships. Note that for the period prior to the introduction of enterprise bargaining in the early 1990s, there is neither an economically or statistically significant relationship between productivity and compensation. The real wage ‘overhang’ noted earlier would work against finding such a relationship.

Table 2 re-estimates the model based on hours worked by employees rather than employed persons. Because the former data are only available from 1991, the model is estimated for the post-enterprise bargaining period.

Table 2: Long-run response of producer wage (based on employee hours) to labour productivity

|

|

Post-ent. barg. |

Post-2000 |

|

Productivity |

0.67*** |

0.52*** |

|

Underutilisation |

0.03 |

0.14*** |

|

Speed of adjustment |

-0.20 |

-0.40 |

|

F-bounds test stat. |

2.30 |

5.38*** |

|

t-bounds test stat |

-2.41 |

-3.81** |

For the period since the introduction of enterprise bargaining, the employee hours based measure of real wages shows a less than one for one relationship with productivity, although this is not a statistically significant long-run relationship. For the period since 2000, the coefficient on productivity weakens to around 0.5 per cent and a statistically significant long-run relationship is found. This result is heavily influenced by the most recent observations.

Other literature using the real wage price index as the measure of compensation finds a long-run elasticity of real wages growth to productivity growth of 0.26 per cent,38 although these estimates are not directly comparable to the relationship in levels reported in Tables 1 and 2. As a pure price index designed to be invariant to the quality of labour, the wage price index would not necessarily be expected to enjoy a strong relationship with productivity growth.

Labour underutilisation is not an economically or statistically significant determinant of average real compensation in the long-run in Table 1, although there is a positive relationship shown in Table 2. This likely reflects the counter-cyclical nature of real wages growth in Australia, an anomaly long established in the literature on Australian business cycles.39 It is worth noting that the unemployment rate and underutilisation rate are also statistically insignificant in the real wage price index model estimated by Chua and Robinson.40 The speed of adjustment (or error correction term) shows the percentage of the variation from the long-run relationship that is corrected every three months.

While not strictly comparable, these estimates are consistent with Stansbury and Summers’s results for the United States in pointing to an economically and statistically robust relationship between compensation and productivity for Australia, at least for the period since the introduction of enterprise bargaining, although the relationship is quantitatively weaker based on employee hours rather than hours worked by employed persons.

Explaining the labour share of income

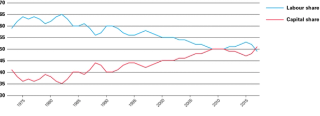

The labour share of income has declined in both Australia and the United States, as well as many other advanced economies, relative to previous decades. The labour share of income in Australia has typically been lower than in the United States on commonly used measures and has fallen by at least as much as the United States, if not more so.41 The lower labour share of income relative to the United States reflects differences in industry composition between the two economies, with industries of differing labour and capital intensity. Figure 4 shows the labour and capital shares of income for the market sector in Australia, with the income of the unincorporated sector apportioned to the labour and capital shares. Cowgill presents alternative estimates to those derived from ABS.42

Figure 4: Labour and capital share of income (%)

The decline in the labour share of income and the associated rise in the capital share in advanced economies is at odds with the traditional view that the labour and capital shares should be approximately constant.

Changes in the labour share can be due to a number of related factors. Labour and capital income can grow at different rates. The economy can change its capital intensity. The labour income share can also change because real compensation does not keep pace with labour productivity, causing the labour share of income to decline.

A decomposition of changes in the labour share in Australia shows that the labour share of income has declined for different reasons in Australia and the United States. In Australia, capital income has grown more strongly than labour income, but labour income still experienced robust growth. In the United States, labour income growth weakened relative to capital income. As Parham puts it, in recent years, Australia experienced the distribution of plenty, while the United States experienced the distribution of pain.43

The terms of trade boom in Australia benefited both capital and labour income. However, an increase in the capital intensity of the economy due to investment in the mining sector and related industries had the effect of increasing the capital share of the economy. The increase in capital intensity was necessary before Australia could capture the benefits of the terms of trade boom in terms of increased output and net exports. These are the same forces that drove a wedge between consumer and producer price inflation noted earlier.

The labour share of income will also decline if real compensation growth lags productivity growth. This is related to the issue of whether technological change is driving a weaker labour share of income. As Stansbury and Summers note:

“...pure technology-based theories of the falling labour share… have a testable implication. If the fall in the labour share has been caused by technological change and the mechanism operates over the short to medium term, we should expect the labour share to fall more quickly in periods where labour productivity growth is more rapid, under the natural assumption that the technological change in question also increases labour productivity.”44

They find that labour productivity does not explain the decline in the labour share of income, at least prior to 2000, with more mixed results since.

Cyclical influences

As noted previously, the decline in the labour share has been widely interpreted as reflecting a decline in the bargaining power of workers relative to employers. The decline in unionisation rates over the same period has led many commentators to suggest these two trends are linked.

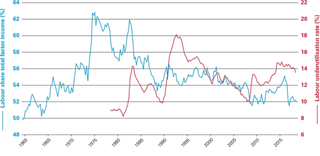

However, the labour share of income can be shown to be counter-cyclical. To the extent that capital income is more cyclical than labour income, then during recessions, the percentage fall in overall income is likely to be greater than the percentage fall in labour income. Since the numerator falls less quickly than the denominator, the labour share of income becomes counter-cyclical, reflecting the cyclical dynamics of the components of factor income.45 The counter-cyclical behaviour of the labour share is evident in Figure 5 comparing the compensation of employees as a share of total factor income with the labour underutilisation rate in Australia.

Figure 5: Labour share and labour underutilisation rate

The labour share tends to increase along with the labour underutilisation rate, most notably during periods of recession such as the early 1980s and ‘90s. It would seem unlikely that workers’ bargaining power or wages would increase when the economy is weak. While the decline in the labour share of income has been secular rather than cyclical, cyclical weakness in the economy should amplify any structural decline in workers’ bargaining power, but this is not evident from the behaviour of the labour share in economic downturns. Changes in the labour share of income in Australia and the United States are due to factors other than changes in workers’ bargaining power.

The role of housing in explaining a rising capital share

The decline in the labour share of income and the associated rise in the capital share would appear to be a stylised fact for many advanced economies. US economist Matt Rognlie shows that the increase in the capital share in the United States and other G7 economies is entirely explained by housing. As Rognlie notes:

“the rise in housing’s contribution to the capital share can be explained in part as the result of scarcity. The rising real cost of residential investment and the limited quantity of residential land have conspired to make housing more expensive, and given low elasticities of substitution this has meant a rise in housing’s share of income. With these trends in mind, policymakers concerned about the distribution of income should keep an eye on housing costs.”46

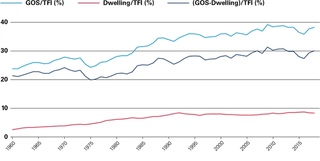

Australia shows a very similar trend to the United States in terms of housing’s contribution to the capital share with housing’s share of total factor income rising from 2.4 per cent in 1960 to 8.2 per cent most recently (Figure 6). Housing accounts for 40 per cent of the increase in gross operating surplus (GOS) share of total factor income in Australia since 1960.

Figure 6: Capital and dwelling share of total factor income (%)

It is worth noting that factor income shares only measure the initial distribution of income.47 Capital income ultimately accrues to those households that own equities and corporate debt, both directly and indirectly via superannuation, although capital income is also more unequally distributed than labour income. Given that the housing stock in Australia is largely owned by households, the increase in the capital share attributable to housing may not be a significant concern for homeowners, but would remain a concern for those unable to access homeownership because of high house prices. Restrictions on housing supply also reduce labour mobility, which directly reduces growth in labour incomes by limiting access to more productive and more highly paid jobs. US evidence suggests that restrictions on housing supply have reduced economic growth by 50 per cent between 1964 and 2009.48 Housing supply regulations help explain why regional income convergence in the United States has declined over time.49

The role of housing in driving the increase in the overall capital share suggests that those concerned about income inequality should focus on improving the supply of housing rather than the bargaining power of workers.

Modelling the labour share of income

As noted earlier, if employee compensation is not keeping pace with productivity, then the labour share of income will fall over time. This would be consistent with the idea that technological change has driven reductions in the labour share.50 However, Stansbury and Summers’s results indicate that labour productivity does not explain changes in the labour share of income before 2000, although their results are more mixed for the period since 2000.

I follow a similar approach in modelling the labour share of income shown in Figure 4 in terms of labour productivity and the two components of labour productivity growth, the capital-labour ratio and multifactor productivity. The same modelling approach is used as previously, but with annual data and lags of up to four years to capture persistence in the labour share over time.51 Three samples are considered. A full sample using all available data adjusted for lags, a sample from 1991-92 for the period since the introduction of enterprise bargaining and since 1999-2000, which has been widely identified as a potential breakpoint in these relationships in both Australia and the United States.

Like Stansbury and Summers, I find a small negative effect of labour productivity on the labour share, but this is not a statistically significant long-run relationship at conventional significance levels (Table 3). Unlike Stansbury and Summers, the post-2000 period does not look exceptional in this regard.

Table 3: Long-run response of the labour share of income to labour productivity

|

|

Full sample |

Post-ent. barg. |

Post-2000 |

|

Labour productivity |

-0.28*** |

-0.16* |

-0.17 |

|

Speed of adjustment |

-0.42 |

-0.26 |

-0.28 |

|

F-bounds test stat. |

5.33* |

3.46 |

2.29 |

|

t-bounds test stat |

-3.15* |

-1.87 |

-0.93 |

Labour productivity can be decomposed into contributions from the capital-labour ratio per hour worked (capital intensity) and multifactor productivity per hour worked (MFP). Substituting these variables for labour productivity in the above model yields the results shown in Table 4.

Table 4: Long-run response of the labour share of income to capital intensity and MFP

|

|

Full sample |

Post-ent. barg. |

Post-2000 |

|

Capital intensity |

-0.16*** |

-0.16*** |

-0.26*** |

|

MFP |

-0.13 |

-0.16 |

-0.19* |

|

Speed of adjustment |

-0.55 |

-0.54 |

-1.30 |

|

F-bounds test stat. |

3.73 |

6.68*** |

15.87*** |

|

t-bounds test stat |

-3.29* |

-4.25*** |

-5.70*** |

Splitting labour productivity into its components shows that capital intensity has the predicated negative effect on the labour share of income. Multifactor productivity subtracts from the labour share in the first two sample periods, but contributes positively to the labour share in the period since 2000. The long-run relationship is statistically significant in the post-1992 samples. Note the very fast speed of adjustment factor in the post-2000, implying the adjustment to the long-run relationship occurs in less than a year.

These results are consistent with Stansbury and Summers, who find “no apparent relationship between changes in the rate of productivity growth and changes in the labour share before 2000” and conclude “the results do not tend to support theories which posit a long-term underlying relationship between technology and the labour share”.52 However, Stansbury and Summers do find a statistically significant effect for the period 2000-2013.

Explaining nominal wages

Nominal wages growth can be thought of as the sum of productivity growth and the inflation rate. However, this relationship is complicated by many of the factors discussed above, including lags. Expected rather than actual inflation will determine the wage setting behaviour of employers and employees, but this is not something we directly observe. Expected inflation in turn reflects expectations for monetary policy. The Reserve Bank controls inflation largely through its control over inflation expectations, which then determines price and wage setting behaviour. Under an inflation targeting regime, only inflation expectations should have explanatory power for inflation outcomes if monetary policy is fully credible. If other variables forecast inflation, this likely reflects a failure of monetary policy to adjust to economic conditions.

Chua and Robinson note that the contribution of inflation expectations to nominal wages growth has fallen considerably in recent years. Their decomposition of recent nominal wage growth outcomes points to lower inflation expectations and productivity growth as the main contributors, with labour market slack playing a relatively modest role.53 Yet the Reserve Bank continues to view wages and inflation as primarily a function of the unemployment rate and its deviation from an estimated non-inflationary rate.54 Many of the RBA’s inflation models are based on long-run equilibrium relationships between unit labour costs, import prices and inflation. Yet the data frequently reject mark-up models of inflation.55

An alternative model views nominal wages growth as a function of nominal GDP growth. Indeed, compensation of employees is the largest component of nominal GDP measured on an income basis. This approach is significant from a policy perspective, because nominal GDP is fully determined by the central bank’s conduct of monetary policy, at least over the medium to long-term time horizons that matter for monetary policy.56 This implies that the central bank determines the level and growth rate of nominal wages in aggregate, although not the distribution of wages. Indeed, nominal wages have been suggested as a potential target for the central bank instead of inflation. As the modelling below will suggest, a nominal GDP rather than an inflation target would serve as a de facto target for aggregate wages.

The relationship between compensation and nominal GDP can be estimated using the same modelling approach employed above. In this case, we examine the relationship between compensation of employees on a national accounts basis and nominal GDP (NGDP), again controlling for undertuilisation in the labour market. In addition to the full sample period since Q3 1978 (adjusted for lags), I consider sub-samples for the period before and after the introduction of enterprise bargaining in 1992. Centralised wage fixing could be expected to hold wages either above or below their equilibrium level over some parts of the sample. Note that 1992 also roughly coincides with the move towards inflation targeting on the part of the Reserve Bank. The results are shown in Table 5.

Table 5: Long-run response of compensation of employees to nominal GDP

|

|

Full sample |

Pre-ent. barg. |

Post-ent. barg. |

|

Nominal GDP |

0.91*** |

0.89*** |

0.95*** |

|

Underutilisation |

-0.30** |

-0.18 |

-0.07 |

|

Speed of adjustment |

-0.11 |

-0.20 |

-0.19 |

|

F-bounds test stat. |

23.39*** |

8.86 |

10.34*** |

|

t-bounds test stat |

-2.78 |

-1.79 |

-3.81*** |

The test statistics in Table 5 indicate that for the period since the introduction of enterprise bargaining and inflation targeting, there is a robust long-run relationship between compensation of employees and nominal GDP, with an elasticity very close to one. Note that this can also be viewed as a test of whether the labour share of income as measured by compensation of employees is stable over the sample period, implying that it is. Note that labour market underutilisation does not enter the relationship in an economically or statistically significant way.

While quantitatively similar, the long-run relationship prior to 1992 is not statistically significant. This is not surprising given the behaviour of wages under centralised wage fixing already noted, which served to prevent nominal wages from equilibrating.

The estimated relationship implies that the Reserve Bank enjoys considerable leverage over the overall level and growth rate of aggregate employee compensation through its role in determining the level of nominal GDP. This adds to the case for the adoption of a market-driven nominal income targeting regime instead of inflation targeting, similar to that advocated in the United States by Scott Sumner.57 However, the full case for nominal GDP targeting lies beyond the scope of this paper.

Conclusion

Nominal and real wages growth has shown weakness in both the United States and Australia in recent years. In Australia, real compensation of employees has lagged productivity, particularly in the last five years. However, the long-run relationship between real compensation and productivity remains intact. Similar to US studies, I find that an increase in labour productivity of one per cent raises real compensation of employees per hour by between 0.7 per cent and 0.9 per cent for the period since the introduction of enterprise bargaining. As with the United States, there is evidence of a weaker relationship since 2000.

Both the United States and Australia have seen a trend decline in the labour share of income, which has been widely interpreted as a decline in workers’ bargaining power translating into weaker wages growth. In Australia, the decline in the labour share of income has been driven by the increased capital intensity of the Australian economy as a result of investment in the mining sector seeking to capitalise on the terms of trade boom. Capital income growth has outpaced growth in labour income, but labour income has also increased.

Even in the presence of a declining labour share of income, American households with below median incomes have enjoyed significant growth in consumption between 1960 and 2015.58 Similar to US studies, I find that labour productivity does not have a long-run relationship with the labour share of income. When labour productivity is decomposed into the capital-labour ratio and multifactor productivity, it is the capital-labour ratio that better explains the labour share of income.

The long-term decline in the labour share of income in the United States and Australia is largely attributable to the rising share of housing in capital income.

The labour share of income is counter-cyclical, rising when labour underutilisation increases during economic downturns. These cyclical dynamics argue against the view that the labour share of income is a proxy for workers’ bargaining power. Instead, the long-term decline in the labour share of income in the United States and Australia is largely attributable to the rising share of housing in capital income.

The strength of the relationship between compensation and productivity does not preclude rising wage or income inequality, a fact acknowledged by both sides of the ‘decoupling’ debate in the United States. As Robert Lawrence says, “there are numerous explanations for rising inequality that are consistent with the assumption that labour is paid its marginal product”.59

However, there is a danger in confusing the two issues. If the compensation-productivity nexus is thought to be broken based on inappropriate measures of compensation, this may lead policymakers to neglect policies that raise productivity in the belief this will not help typical workers. Instead, policymakers may focus too much on redistributive policies at the expense of productivity-enhancing policies. But productivity growth still remains the best way to lift average worker compensation. The subsequent distribution of productivity gains is a second-order issue. As Stansbury and Summers conclude:

“the potential effect of raising productivity growth on the average American’s pay may be as great as the effect of policies to reverse trends in income inequality. Conversely, they suggest that a continued productivity slowdown should be a major concern for those hoping for increases in real compensation for middle income workers.”60

There is no reason to abandon the competitive model of wage determination based on the relationship between worker compensation and productivity.

Aggregate compensation of employees also enjoys a robust relationship with nominal GDP, which gives the Reserve Bank considerable leverage over nominal wages growth if it chooses to exercise it. The RBA can lift nominal wages growth by credibly committing to return inflation to the middle of its 2-3 per cent target range. Low nominal wages growth is merely symptomatic of declining inflation expectations driven by the RBA’s failure to meet the central tendency of its medium-term inflation target since 2014. Waiting for the labour market to tighten sufficiently to raise wages in the hope that this might flow through to inflation gets the relationship between wages and inflation backwards.

Appendix

The Appendix: Model specification can be seen in the PDF version of this report.