Executive summary

It is possible the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) will need to lower the cash rate by more than its current level of 1.25 per cent to maintain nominal stability if there is adverse shock to the Australian economy. This will require the RBA to adopt a negative cash rate or change its operating instrument for monetary policy to the size and composition of its own balance sheet, also known as quantitative easing (QE).

If necessary, the RBA should transition quickly from a cash rate target to large and open-ended purchases of government bonds, as well as non-government debt and other securities, as its main monetary policy-operating instrument. These purchases should be tied to achieving explicit macroeconomic objectives, in particular, maintaining the stability of nominal spending.

The US Federal Reserve (Fed) engaged in large-scale asset purchases from 2009 to 2014 and offers important lessons for how best to frame a QE program.

The US experience shows that quantitative easing is effective in improving macroeconomic conditions and that the supposed zero lower bound on official interest rates is not a constraint on the effectiveness of monetary policy. The RBA is not in danger of ‘running out of ammunition’.

The cumulative effect of QE in the United States is estimated to have been the equivalent of a 250 basis point reduction in the federal funds rate, with effects on output and inflation comparable to a reduction in official rates, while reducing the unemployment rate by as much as one per cent.

The US Federal Reserve engaged in large-scale asset purchases from 2009 to 2014 and offers important lessons for how the Reserve Bank of Australia could best frame a quantitative easing program.

However, US experience also warns against the consequences of being too timid in the implementation of QE. The United States was slow to lower its official interest rate to near zero and embark on QE in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. The first episode of QE was limited in size and duration. The Fed’s policy of paying interest on reserves also blunted the transmission of QE to the broader economy.

Empirical estimates of QE’s effectiveness in the United States between 2009 and 2014 should thus be viewed as a lower bound.

The Fed ended its asset purchases in 2014 and raised the federal funds rate prematurely in December 2015. Like the RBA, the Fed has undershot its inflation target in recent years, indicating that monetary policy has been unintentionally tight, not ‘ultra-easy’.

The US experience suggests the Reserve Bank would need to buy securities equivalent to around 1.5 per cent of GDP to achieve the same effect as a 0.25 percentage point reduction in the official cash rate.

If the RBA were to implement a QE program equivalent as a share of GDP to that of the US Federal Reserve between 2009 and 2014, it would need to purchase assets to the value of AU$550 billion. This is around 70 per cent of the AU$783.4 billion in long-term government (Commonwealth and state) debt securities outstanding in Australia at the end of 2018.

The RBA could also broaden asset purchases to include non-government and non-debt securities. The stock of debt and other securities in Australia is not an impediment to implementing QE.

There are good reasons for thinking QE could be much more potent in Australia if the RBA avoids making some of the US Fed’s mistakes. In that event, the size of QE in Australia could be much smaller as a share of GDP.

The mistaken belief that monetary policy is ineffective at the zero bound can mislead policymakers into relying too heavily on fiscal policy and other interventions to achieve macroeconomic stabilisation objectives.

Fiscal policy is ineffective in stabilising the economy in the presence of an inflation targeting central bank and a floating exchange rate, even when the official cash rate is at zero.

Introduction

The Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA) official cash rate (OCR) has been lowered from 4.75 per cent in October 2011 to 1.25 per cent in June 2019 as Australia’s inflation rate has fallen. The OCR was kept on hold for 30 months from August 2016 to May 2019. The inflation rate has been below the mid-point of the RBA’s 2-3 per cent target range since 2014, a prolonged undershoot without precedent in the more than 25-year history of inflation targeting. The RBA has explicitly traded-off the inflation target against financial stability concerns, worried that further reductions in the cash rate might lead to increased leverage on the part of households, increasing their exposure to future adverse economic shocks.1 This failure to prioritise the inflation target has contributed to further declines in inflation, which demands further reductions in the cash rate if the RBA is to meet its agreement with the government on inflation.

With the nominal cash rate already very low by historical standards, it is possible the Reserve Bank will need to lower the cash rate by more than 125 basis points to maintain nominal stability, especially if there is adverse shock to the Australian economy. This will require the RBA to adopt a negative cash rate or change its operating instrument for monetary policy from the cash rate to the size and composition of its balance sheet, also known as quantitative easing (QE).

The Federal Reserve (Fed) in the United States engaged in large scale-asset purchases from 2009 to 2014 and offers important lessons for how best to implement quantitative easing. The US experience shows that quantitative easing is effective in improving macroeconomic conditions and that the supposed zero lower bound on official interest rates is not a constraint on the effectiveness of monetary policy.

The US experience shows that quantitative easing is effective in improving macroeconomic conditions and that the supposed zero lower bound on official interest rates is not a constraint on the effectiveness of monetary policy.

However, US experience also warns against being too timid in the implementation of QE. The United States was slow to lower its official interest rate to near zero and embark on QE in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. The first episode of QE was limited in size and duration. The Fed’s policy of paying interest on reserves blunted the transmission of QE to the broader economy. The Fed subsequently engaged in a more open-ended program of asset purchases, but undermined its effectiveness by continually talking up the prospects for an exit from QE through its forward guidance on policy. The Federal Reserve ended its asset purchases in 2014 and raised the federal funds rate prematurely in December 2015. Like the RBA, the Fed has undershot its inflation target in recent years, indicating that monetary policy has been unintentionally tight, not ‘ultra-easy’ as some would have it.

The Reserve Bank should prepare to implement QE in the event that the nominal official cash rate cannot be effectively lowered below zero. While it is possible to implement a negative cash rate, there are questions as to how this would be transmitted to the broader economy via wholesale and retail lending rates. In particular, the inability of banks to pass on negative deposit rates could constrain the transmission of negative official interest rates.2

By contrast, QE is a proven approach to easing monetary policy. To prepare financial markets and the public for this contingency, the RBA should clearly communicate that the zero bound on the official cash rate is not a constraint on the effectiveness of monetary policy. If necessary, it should transition quickly from a cash rate target to large and open-ended purchases of government and non-government securities as its main monetary policy operating instrument. These purchases should be tied to achieving explicit macroeconomic objectives, in particular, maintaining 2-3 per cent inflation and the stability of nominal spending.

The US experience with QE suggests the Reserve Bank would need to buy securities equivalent to around 1.5 per cent of GDP to achieve the same effect as a 0.25 percentage point reduction in the official cash rate. QE on the scale implemented by the US Federal Reserve between 2009 and 2014 would likely require the RBA to extend asset purchases beyond government bonds to include non-government and non-debt securities. However, there are good reasons for thinking QE could be much more potent in Australia if the RBA avoids making some of the Fed’s mistakes. In that event, QE in Australia could be much smaller as a share of GDP.

The US experience with QE: What did the Fed do?

The Federal Reserve began lowering its official interest rate (the federal funds rate) in September 2007 in response to the emerging financial crisis. However, the federal funds rate did not approach zero until December 2008. The failure of monetary policy to respond quickly to the emerging economic downturn in 2008 was a factor in the severity of the subsequent ‘Great Recession’.3 The Fed began purchasing assets as part of its effort to stabilise financial markets in 2008. As the Fed sought to put a floor under the federal funds rate at near zero, it turned to asset purchases as an alternative approach to implementing monetary policy.

The Fed’s asset purchases were complemented by ‘forward guidance’, a process by which the Fed signalled the likely future path of the federal funds rate.4 In particular, the Fed implied that official interest rates would be kept low for an extended period, although this guidance was frequently revised in terms of both timing and its relationship to future economic conditions. It is controversial whether this signalling channel was more or less potent than QE and whether QE was even necessary for forward guidance to be effective. However, QE can be seen as a mechanism through which forward guidance can be given increased credibility.

QE was implemented in four distinct episodes starting in November 2008 and ending in 2014. These episodes became known as QE1; QE2; the Maturity Extension Program, also called ‘Operation Twist’; and QE3. Each episode had its own characteristics and, together with the stop-start nature of QE, provides a policy experiment from which we can derive lessons for how best to implement QE in Australia, should that become necessary for the continued effective conduct of monetary policy in response to adverse economic shocks.

QE1: November 2008 to August 2009

In October 2008, the Federal Reserve began paying interest on reserves held by financial institutions with the Fed. The policy was designed to put a floor under the effective federal funds rate at around zero per cent so that the Fed could then adjust the size and composition of its balance sheet independently of the federal funds rate, facilitating the introduction of what became known as QE. However, the floor system also served to diminish the effectiveness of QE by providing an incentive for financial institutions to hold excess reserves at the Fed, reducing the transmission of QE to broader monetary and credit aggregates.5 QE largely accommodated the demand for excess reserves on the part of financial institutions, blunting but not negating its transmission to the broader economy via changes in asset prices and expectations for the future path of short-term interest rates.

In November 2008, the Federal Reserve indicated that it would purchase US$600 million in agency bonds and mortgage-backed securities as part of its effort to prop-up the mortgage market, although these purchases were offset by other asset sales. This initial asset purchase program was expanded in March 2009 to US$1.75 trillion, including US$1.25 trillion in mortgage-backed securities, US$200 billion in agency debt and US$300 billion in US government bonds (Treasuries), to be purchased by December 2009. These purchases amounted to around 12 per cent of US GDP at the time.6

At its December 2008 meeting, the Federal Open Market Committee also began forward guidance in relation to the federal funds rate, noting that ‘weak economic conditions are likely to warrant exceptionally low levels of the federal funds rate for some time’.7 At its March 2009 meeting, the Committee replaced ‘for some time’ with ‘for an extended period’ in its post-meeting statement.

QE1 played an important role in stabilising financial markets, as well as allowing monetary policy to support economic activity once the zero lower bound on nominal interest rates came to be seen as a constraint on policy conducted via the federal funds rate. However, QE1 was announced as a one-off policy action, with a finite amount of asset purchases to be made by a given date. The close-ended nature of QE1 limited its effectiveness, as did the policy of paying interest on reserves.

For comparison, 12 per cent of Australian nominal GDP for calendar 2018 was around AU$228 billion. This is equivalent to around 29 per cent of the AU$783.4 billion in long-term Australian government (Commonwealth and state) debt securities outstanding as at the end of 2018.8

QE2: November 2010 to June 2011

In November 2010, the Fed announced its intention to purchase an additional US$600 billion in US Treasury bonds to be completed by June 2011. The program amounted to around four per cent of US GDP at the time. The Federal Reserve also indicated that quantitative policy instruments would continue to be used to achieve its macroeconomic objectives. QE2 was thus a more open-ended policy commitment than QE1, although still characterised by an initially fixed and pre-announced program of asset purchases.

At its August 2011 meeting, the FOMC announced it would keep the federal funds rate at exceptionally low levels ‘at least through mid-2013’. At its January 2012 meeting, it replaced ‘at least through mid-2013’ with ‘at least through late 2014’. In the event, the federal funds rate would not be raised until December 2015. The Fed’s continual signalling of prospective increases in the federal funds rate and an end to QE likely weakened its effectiveness through its impact on financial market expectations for future interest rates.

‘Operation Twist’ — The Maturity Extension Program: September 2012 to December 2012

In September 2011, the Fed announced it would purchase US$400 billion in Treasury bonds with a maturity of greater than six years, while selling securities with maturities of less than three years over nine months. In June 2012, the program was extended until the end of 2012, totalling US$667 billion or four per cent of GDP.9

The Maturity Extension Program (MEP) sought to amplify the effect of QE on longer-term interest rates, but the accompanying sales of shorter-term securities of equal value limited the expansion in the Fed’s balance sheet and the effectiveness of the policy. This is one of several decisions that limited the overall effectiveness of monetary policy under QE, based on misplaced fears the expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet would be excessively inflationary.

QE3: September 2012 to October 2014

QE3 overlapped with the MEP. In September 2012, the Fed entered into open-ended purchases of mortgage-backed securities at a rate of US$40 billion per month. In December 2012, it entered into open-ended purchases of Treasury bonds at a rate of US$45 billion per month and discontinued the sale of short-term debt securities, bringing total monthly asset purchases to US$85 billion per month. In December 2013, the Fed slowed the pace of purchases to US$35 billion in MBS and US$40 billion in Treasury bonds, the so-called ‘taper’. The pace slowed further until the United States discontinued its quantitative easing program in October 2014, by which time, the Fed’s QE3 asset purchases had totalled US$1.5 trillion or nine per cent of GDP.

The more open-ended nature of QE3 enabled the Fed to relate the size and pace of the program to the evolution of macroeconomic conditions and so more effectively condition market expectations. However, the Fed changed its forward guidance four times between December 2012 and October 2014.10 While the changes in guidance were intended to strengthen QE, by continually shifting the goal posts, the Fed also weakened the credibility of policy. The end of QE in October 2014 and subsequent increase in the federal funds rate in December 2015 was arguably premature. The fact that it took another 12 months before the Fed was able to further raise the federal funds rate in December 2016 is an effective admission that monetary policy was tightened prematurely.

Table 1 summarises the main QE episodes and quantifies their economic significance in Australian dollar terms based on equivalent shares of Australian nominal GDP for the year-ended 2018.

Table 1: Summary of QE episodes in US$ and AU$ equivalent terms

|

Episode |

Asset purchases (US$) |

Share of US GDP (%) |

AU$ millions equivalent |

|

QE1 |

$1.25 trillion MBS, $200 billion agency debt, $300 billion US Treasuries |

12 |

227,488 |

|

QE2 |

$600 billion long-term US Treasuries |

4 |

75,829 |

|

MEP |

$667 billion long-term US Treasuries |

4 |

75,829 |

|

QE3 |

$1.5 trillion US Treasuries and MBS |

9 |

170,616 |

|

Total |

|

29 |

549,763 |

If Australia were to implement QE on the same scale as a share of GDP as the Federal Reserve between 2009 and 2014, the Reserve Bank would need to purchase assets to the value of about AU$550 billion. This is around 70 per cent of the AU$783.4 billion in long-term government (Commonwealth and state) debt securities outstanding in Australia at the end of 2018. Residential mortgage-backed securities outstanding were AU$114.8 billion at the end of 2018.

What effect did QE have in the United States?

Quantitative easing is an operating instrument rather than a monetary policy as such. Its effectiveness as an operating instrument depends on the policy framework in which it is announced and implemented. Studies which attempt to estimate the effects on QE typically take these policy frameworks and central bank operating procedures as given when, in fact, they are critical for understanding QE’s impact.

The effectiveness of QE in the United States was diminished by a number of features of the policy framework and operating procedures associated with its implementation. The Fed’s forward guidance and the policy of paying interest on the reserves held by financial institutions at the Fed to put a slightly positive floor under the effective federal funds rate reduced the effectiveness of QE.11 However, these are not criticisms of QE as such, only the monetary control framework in which it was implemented. In fact, it implies that QE could be much more effective than empirical studies of the US experience have found to date.

The Reserve Bank of Australia uses a corridor rather than a floor system for its official cash rate. Under a corridor system, there is no cost advantage to holding reserves versus borrowing any shortfall from the Reserve Bank. The demand curve for reserves lies within the interest rate channel set by the Reserve Bank.12 Whether the corridor system would remain viable in the presence of QE is an open question, but it is always possible for the RBA to penalise rather than reward financial institutions for holding excess reserves with the central bank.

The effects of QE can be viewed in terms of both intermediate policy objectives, such as lowering interest rates, as well as final policy objectives, such as supporting the growth rate and level of nominal demand. Empirical studies have mostly focused on the effect on interest rates and then assumed that other economic variables respond positively to lower interest rates. Estimating the impact on variables like inflation, economic growth and employment is less straightforward, but that is true for changes in any monetary policy instrument.

QE is typically thought to operate through its effect on longer-term, market-determined interest rates. All else equal, central bank bond purchases raise the price of these securities and lower their yields. QE also operates through a number of other channels, including the aforementioned forward guidance, lower risk premia and credit spreads, and a weaker exchange rate. As with monetary policy conducted via an official interest rate, transmission to final policy objectives such as inflation and output occurs through a variety of channels. Given the relatively small stock of debt securities in Australia, QE could be expected to be more potent than in the United States. For a small open economy like Australia, the exchange rate channel is also likely to prove more powerful than in a relatively closed economy like the United States.

The cumulative effect of QE in the United States is estimated to have been the equivalent of a 250 basis point reduction in the federal funds rate, with effects on output and inflation comparable to a reduction in the official interest rate, while reducing the unemployment rate by as much as one per cent.

This section follows Gagnon in summarising the empirical studies of QE in the United States to date.13 These studies mainly focus on how the Fed’s purchases of government bonds and the change in the composition of its balance sheet affected market-determined, longer-term interest rates (the portfolio balance effect). Given the way in which the operating procedures for US monetary policy sought to limit QE’s impact, these estimates can be viewed as a lower bound for QE’s potential effectiveness. In the absence of the policy of paying interest on reserves, QE could be expected to have a more expansionary effect on monetary and credit aggregates, which would enhance its effectiveness in stimulating nominal spending.

According to Gagnon, “rarely, if ever, have economists studying a specific question reached such a widely held consensus so quickly. But this consensus has yet to spread more broadly within the economics profession or the wider world."14 RBA Deputy Governor Guy Debelle has said that QE might be subject to “diminishing returns” but also notes that, “I acknowledge that much of the empirical evidence tends not to find that”.15 The consensus of academic economists is that QE in the United States lowered long-term interest rates by around 100 basis points (see Table 2), although some studies have found only ‘modest and uncertain effects on yields’.16 Lower long-term government bond yields have been shown to spillover into lower interest rates on other non-government debt securities, a weaker exchange rate and higher stock prices. The cumulative effect of QE in the United States is estimated to have been the equivalent of a 250 basis point reduction in the federal funds rate, with effects on output and inflation comparable to a reduction in the official interest rate, while reducing the unemployment rate by as much as one per cent.17

Table 2: Estimates of effects of QE bond purchases on 10-year yields

(purchases normalised to 10 per cent of GDP)

|

Study |

Sample |

Method |

Yield reduction |

|

Greenwood and Vayanos (2008)[a] |

1952 – 2005 |

Time series |

82 |

|

Gagnon, Raskin, Remache, and Sack (2011) |

2008 – 2009 |

Event study |

78 |

|

Krishnamurthy and Vissing-Jorgensen (2011) |

2008 – 2009 |

Event study |

91 |

|

Hamilton and Wu (2012) |

1990 – 2007 |

Affine model |

47 |

|

Swanson (2011) |

1961 |

Event study |

88 |

|

D’Amico and King (2013) |

2009 – 2010 |

Micro event study |

240 |

|

D’Amico, English, López-Salido, and Nelson (2012) |

2002 – 2008 |

Weekly time series |

165 |

|

Li and Wei (2012) |

1994 – 2007 |

Affine model of TP |

57 |

|

Rosa (2012) |

2008 – 2010 |

Event study |

42 |

|

Neely (2012) |

2008 – 2009 |

Event study |

84 |

|

Bauer and Neely (2012) |

2008 – 2009 |

Event study |

80 |

|

Bauer and Rudebusch (2011)[b] |

2008 – 2009 |

Event study TP only |

44 |

|

Christensen and Rudebusch (2012)[b] |

2008 – 2009 |

Event study TP only |

26 |

|

Chadha, Turner, and Zampolli (2013) |

1990 – 2008 |

Time series TP only |

117* |

|

Swanson (2015)[b] |

2009 – 2015 |

Yield curve TP only |

40 |

|

Christensen and Rudebusch (2016)[b] |

2008 – 2009 |

Event study TP only |

15 |

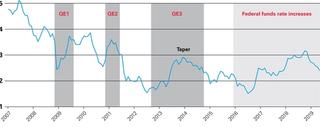

Confusion arises from the fact that long-term interest rates in the United States typically rose during QE episodes and declined during the intervening periods. Yields also rose in response to QE-related announcements.18 While QE is generally conceived to work through lowering long-term interest rates, that is only the static or liquidity effect. The dynamic effect is to raise expectations for long-term economic growth and inflation and this is also reflected in longer-term interest rates, which consistently rose during QE episodes and fell during the intervening periods (Figure 1). Notice that the end of QE saw a decline in long-term bond yields, implying weakening expectations for economic growth and inflation. Predictions that the end of QE would see rising interest rates have not been borne out. This argues against the notion that long-term interest rates were artificially suppressed by QE. In fact, long-term interest rates behaved as they should. Long-term yields should fall if monetary policy is prematurely tightened, which is what we see in Figure 1. The stop-start nature of QE provides something approximating a policy experiment in terms of assessing its implications for interest rates and other macroeconomic variables.

Figure 1: US ten-year bond yield (%) and QE episodes

For many advanced economies, including Australia and the United States, the decade since the financial crisis of 2008 has been characterised by low interest rates and low inflation. Economic performance has been subdued along a number of dimensions, including productivity growth and investment spending. The Reserve Bank has noted the ‘disappointingly low level of investment spending’ across developed economies, including non-mining business investment in Australia.19

A popular narrative to explain this post-crisis macroeconomic and financial environment takes as its starting point the assumption that monetary policy around the world has been exceptionally easy because official interest rates have been set at historically low levels (including at or below zero per cent) and central banks have resorted to quantitative operating instruments. Monetary policy in the United States, Japan, the Eurozone and even Australia has often been described as ‘ultra-loose’ and the use of alternative monetary policy operating instruments as ‘unconventional’ or ‘unorthodox’.

There have also been calls for central banks to reconsider their approach to inflation targeting and for greater reliance on fiscal policy as a macroeconomic policy instrument.

This narrative immediately runs into an obvious problem. If monetary policy has been so easy, why has inflation and nominal spending been so low and why has investment been slow to respond? This has led many to the conclusion that monetary policy is limited in its effectiveness, either because it is constrained by the zero lower bound or because quantitative easing is ineffective. There have also been calls for central banks to reconsider their approach to inflation targeting and for greater reliance on fiscal policy as a macroeconomic policy instrument.

This macroeconomic narrative has a financial market counterpart. It is claimed that monetary policy has kept interest rates artificially low and this has contributed to artificially high asset prices, artificially low asset price volatility and low price dispersion across asset classes. Some have gone so far as to characterise this as financial repression. Central banks have also been accused of engaging in beggar-thy-neighbour exchange rate depreciation or ‘currency wars’.

This narrative about the effects of monetary policy on financial markets sits uneasily with the narrative about the effects on inflation and economic performance. If monetary policy is so potent an influence on market-determined interest rates and other financial market prices, why is it deemed to be less effective in relation to macroeconomic variables such as investment spending given that financial markets are one of the main transmission mechanisms for monetary policy?

The problem with these narratives is that they proceed from a false assumption that monetary policy in the aftermath of the financial crisis has been ‘easy’. The effective stance of monetary policy cannot be inferred from its operating instruments. It can only be inferred from inflation expectations and inflation outcomes, as well as nominal spending. Milton Friedman made this argument more than 50 years ago:

As an empirical matter, low interest rates are a sign that monetary policy has been tight — in the sense that the quantity of money has grown slowly; high interest rates are a sign that monetary policy has been easy — in the sense that the quantity of money has grown rapidly. The broadest facts of experience run in precisely the opposite direction from that which the financial community and academic economists have all generally taken for granted.20

Nothing in the subsequent 50 years has invalidated Friedman’s empirical observation, both about the relationship between the level of interest rates and the stance of monetary policy, but also the failure of the financial community and academic economists to appreciate this insight.

In a macroeconomic environment in which the demand for safe assets, including the demand for money is elevated (or, inversely, the velocity of money is low), it is not surprising that monetary policy has to work harder to achieve a given inflation target. In the United States, Europe and Japan, quantitative easing (QE) has accommodated an increased demand for safe assets, which was an important contribution to stabilising inflation and nominal spending, but QE has not flooded the world with excess liquidity as many assume.

Milton Friedman used the analogy of a thermostat to describe how monetary policy needs to be calibrated to obtain the desired macroeconomic outcomes based on prevailing environmental conditions, including money demand/velocity.21 If we think monetary policy is less effective (which is possible in an environment of increased money demand) then that is an argument for doing more monetary policy, not less. Even if the effects of QE are thought to be modest, so long as there is some effect, it is possible to calibrate the size of QE to achieve the desired macroeconomic objectives, in particular, rates of inflation consistent with the central tendency of the inflation targeting framework. However, policymakers are not limited to changes in the size of QE to increase its effectiveness. As we have seen, the overall framework for monetary policy can enhance its effectiveness so that a smaller asset buying program can have more pronounced effects.

What did the Fed get wrong? Lessons for Australia

Quantitative easing made an important contribution to stabilising US financial markets and the economy in the wake of the financial crisis. However, persistently low inflation in the United States also implies that monetary policy has been unintentionally tight rather than easy. Rather than being an indication of monetary policy ineffectiveness, this implies that QE was not used as effectively as it could have been.

Apart from QE’s size and composition, the way in which the policy was framed and conditioned by forward guidance limited its effectiveness, as did the policy of paying interest on the reserves. By all accounts, the Federal Reserve was nervous that QE might be too potent, leading to an outbreak of inflation. It hobbled QE in such a way that a larger program of asset purchases over a longer period of time was ultimately needed to stabilise the US economy. In the end, the recovery from the 2007-09 recession was slower and more drawn out than it needed to be because monetary policy was not used aggressively enough.

The main lesson from this experience for Australia is that the Reserve Bank should transition quickly from the cash rate to QE as its main operating instrument for monetary policy before the level of the nominal cash rate becomes a constraint on the effective stance of monetary policy. The announced program of asset purchases should be open-ended in size and scope and tied explicitly to the achievement of macroeconomic objectives and not an expected future end date. QE in Australia should avoid merely accommodating the demand for excess reserves on the part of financial institutions. By applying the lessons from the US experience with QE, it is likely Australia could obtain a larger effect from a smaller quantity of asset purchases as a share of GDP.

Myths about quantitative easing

There are several widely-believed myths about QE that need to be debunked.

QE is ‘money printing'

QE does not involve ‘printing money’, although may have the effect of increasing the money supply depending on how it is implemented. QE in the United States involved purchasing Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities, adding them to the asset side of the Fed’s balance sheet, alongside the creation of additional currency in circulation and bank reserves on the liabilities side. However, the growth rate of currency in circulation under QE has been little different from its long-run trend. The stock of money, broadly defined, needs to grow over time to accommodate the demand to hold it if the price level is to remain stable. The Federal Reserve supplies currency on demand to financial institutions in exchange for bank reserves. Currency in circulation is driven by the demand to hold it. Financial institutions can also create money, defined more broadly to include other generally accepted media of exchange, through credit creation, but this process is only loosely connected to the Fed’s monetary policy.22 QE was very different from Milton Friedman’s ‘helicopter drop’ of money thought experiment, which gave rise to the moniker ‘Helicopter Ben’ to describe Ben Bernanke’s monetary policy. QE did not involve the US Treasury borrowing directly from the Fed to finance the US federal budget.

The Fed effectively short-circuited QE because it feared the increased liquidity would stoke excessive inflation but ended-up running an overly restrictive monetary policy instead, as evidenced by low inflation and nominal spending.

The reserves held by financial institutions at the Fed, which saw explosive growth as a direct result of QE, are not money in the conventional sense because they cannot be spent. While banks could convert reserves into money (along with the deposits they receive from the public) through the process of credit creation, they chose to hold increased reserves to improve their own balance sheets.

During QE1, the Fed sterilised its emergency lending to financial institutions, reducing the impact of the policy by removing liquidity from some financial institutions to offset the liquidity provided to others. When the Fed was no longer able to sterilise its lending to financial institutions through open market operations, it started paying interest on reserves held by financial institutions at the Fed. As already noted, this put a floor under short-term interest rates and gave financial institutions an even stronger incentive to hold additional reserves. The money multiplier that relates changes in the money base to broader measures of the money supply collapsed as a result. The Fed ensured that the liquidity provided to financial institutions would not make it out into the broader economy. This explains what for many commentators remains a mystery: increases in the money base (reserves held at the Fed plus currency in circulation) did not translate into growth in the broader money supply and higher rates of inflation. The Fed effectively short-circuited QE because it feared the increased liquidity would stoke excessive inflation but ended-up running an overly restrictive monetary policy instead, as evidenced by low inflation and nominal spending.

‘Monetary policy doesn’t work’

The Fed’s failure to use monetary policy as aggressively as it could have gave rise to a myth of monetary policy ineffectiveness. As already noted, because low interest rates have been mistaken for ‘easy’ monetary policy, many commentators assume that monetary policy has been tried and failed. Nothing could be further from the truth. Christina and David Romer have declared the idea that monetary policy is ineffective as ‘the most dangerous idea in Federal Reserve history’.23 They point to disturbing parallels between the views of today’s policymakers and policymakers in the 1930s, which led to the worst macroeconomic disaster of modern times.

Monetary policy is always effective because there is no in-principle limit to the size of a central bank’s balance sheet. Central banks cannot be rendered insolvent, because their balance sheets are denominated in their own, ultimately irredeemable, monetary liabilities. Monetary policy can always do more. In the limiting case, the central bank can purchase every asset in the economy, but long before that point is reached, the public will seek to offload their excess money balances, leading to increased nominal spending. Obviously, this power can be abused, resulting in high rates of inflation or even hyperinflation, as has been seen in countries such as Zimbabwe and Venezuela. But the effectiveness of monetary policy should not be in question. Monetary policy is only ineffective in stabilising inflation and aggregate demand when it is under-utilised or deliberately subordinated to another policy objective, such as maintaining a fixed foreign exchange rate.

Even if one believes the monetary policy transmission mechanism from the money supply and/or interest rates to inflation and nominal spending is somehow impaired, this is an argument for monetary policy to do more not less. As already noted, Milton Friedman used a thermostat analogy to explain how monetary policy should be calibrated.24 Nic Rowe makes a similar analogy to the accelerator on a car. A car may be travelling at a constant speed, but this still requires the driver to continually adjust the throttle to compensate for factors that might otherwise slow the car down or cause it to speed up, such as going up or down a hill. Those who claim that monetary policy is ineffective because they see no relationship between changes in monetary policy and spending are doing the equivalent of saying ‘All you guys who think that gas pedals and hills affect speed are wrong!’ Rowe notes ‘almost all economists are unaware of this important idea’.25

A special case of monetary policy ineffectiveness is the idea of a ‘liquidity trap’. When interest rates on government bonds fall to zero, bonds and cash are said to become perfect substitutes. Since interest rates are the opportunity cost of holding cash, a zero interest rate leads to absolute liquidity preference or an infinite demand to hold cash at the prevailing zero interest rate. Increases in the money supply are hoarded rather than spent and monetary policy is no longer able to increase nominal spending.

The belief that monetary policy is ineffective can mislead policymakers into relying too heavily on fiscal policy and other interventions to achieve macroeconomic stabilisation objectives.

This idea was central to Keynes’s General Theory, although as Scott Sumner notes, Keynes’s one real world example of a liquidity trap was really a constraint imposed by the inter-war gold standard, in which the gold reserve ratio was bounded at zero.26 Under a fiat money regime, monetary policy cannot lose its effectiveness because money is never a perfect substitute for other assets, even at zero interest rates, so long as its liquidity services are valued.

Some countries have seen their long-term government bond yields driven below zero. This is just as likely to reflect a failure to use monetary policy aggressively, lowering expectations for future growth and inflation, rather than a liquidity trap. It is always possible for a central bank to purchase non-government debt and other securities in the event long-term nominal bond yields are driven to zero or below and are no longer viewed as an effective transmission mechanism for monetary policy.

The belief that monetary policy is ineffective can mislead policymakers into relying too heavily on fiscal policy and other interventions to achieve macroeconomic stabilisation objectives. It is actually fiscal policy that is ineffective in the presence of an inflation targeting central bank and a floating exchange.27 As Delong and Olney note:

As a rule, today’s Federal Reserve does routinely neutralize the effects of changes in fiscal policy. Swings in the budget deficit produced by changes in tax laws and spending appropriations have little impact on real GDP unless the Federal Reserve wishes them to…The rule that prevails today and probably will prevail for the next generation is that the Federal Reserve offsets shifts in aggregate demand created by the changing government deficit.28

‘QE promotes inequality’

Another myth about QE is that it promotes inequality. A related view is that it hurts retirees reliant on the yields on interest-bearing securities for their income. Because QE is expected to raise asset prices and assets are disproportionately owned by higher income earners and the wealthy, QE is blamed for widening income inequality. This argument is not limited to those on the left. For example, former Treasurer Joe Hockey told the free market Institute of Economic Affairs that:

Loose monetary policy actually helps the rich to get richer. Why? Because we’ve seen rising asset values. Wealthier people hold the assets.29

Such criticism cannot be uniquely applied to QE, since ‘conventional’ monetary policy through changes in interest rates also works in part via changes in asset prices. But it also ignores the dynamic effect QE has on the economy as a whole, not just returns on specific assets. QE raises asset prices by improving expectations for future economic growth and inflation.

Contractionary monetary policy shocks have in fact been shown to worsen inequality.30 QE by the European Central Bank has been shown to reduce measured inequality in the euro area through its positive effect on wages and by lowering unemployment.31 Similarly, the Bank of England found that ‘the majority of [UK] households have gained from the accommodative stance of monetary policy’ under QE.32 QE reduces inequality when its economy-wide impact is considered. Monetary policy is neutral in the long-run with respect to the real economy and structural issues such as the distribution of income.

‘QE leads to excessive inflation/socialism’

QE in the United States was associated with some of the lowest inflation outcomes in the post-World War Two period. Predictions that QE would lead to excessive inflation were misplaced. The Fed designed QE to limit its inflationary impact. In principle, monetary policy can induce hyperinflation, but this is not an objective that would be viewed as acceptable to policymakers in countries like the United States or Australia. The fact that irresponsible monetary policy can lead to hyperinflation does, however, speak to monetary policy’s potential effectiveness. Whereas fiscal policy is limited by government solvency constraints, monetary policy is only constrained by the amount of inflation the monetary authority is prepared to tolerate.33

Many of the critics of QE on the right are justifiably suspicious of inflation and the idea that it can be used to promote economic activity in a sustainable way. They are also mindful of the possibility central banks will err in creating more inflation than intended. But historical experience suggests that central banks are more likely to err in not supporting nominal demand. This was one of the lessons of Friedman and Schwartz’s examination of the Great Depression34 and Scott Sumner’s examination of Fed policy in the Great Recession.35

There is also a danger that weak economic conditions induced by overly restrictive monetary policy will lead policymakers to use other more interventionist policy instruments. The use of fiscal stimulus by the US and Australian governments during the financial crisis in 2008 was in part the result of a mistaken view that monetary policy was limited in its effectiveness. Weakness in the economy induced by overly tight monetary policy can also fan populist politics of the left and right. While some have gone so far as to suggest that QE is to blame for the rise of left-wing populists like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and ‘millennial socialism’ in the United States,36 this is only true in the sense that excessively tight monetary policy has given rise to increased populism. As Scott Sumner has argued, the effective choice over policy outcomes is between a little more inflation or more socialism.37

Conclusion

The US experience with QE between 2009 and 2014 demonstrates that the zero lower bound on nominal interest rates is not a constraint on the effectiveness of monetary policy. The availability of quantitative operating instruments for monetary policy means that a central bank can never ‘run out of ammunition’.

QE is an operating instrument for policy rather than a monetary policy as such. As with policy conducted via official interest rates, QE’s effectiveness depends on the policy framework in which it is located, as well as how the policy is communicated and executed.

The United States implemented a quantitative easing program equal to around 29 per cent of GDP between 2009 and 2014. The evidence shows that QE was effective in lowering market-determined interest rates, stabilising financial markets and raising expected and actual economic growth and inflation.

The main lesson for the Reserve Bank is that it should quickly transition from using the official cash rate to outright purchases of financial assets before the level of the nominal official interest rate becomes a constraint on the ability of monetary policy to stabilise nominal spending.

However, the Fed also curtailed the effectiveness of QE in a number of ways. The early efforts at QE were explicitly limited in size and duration. Only during QE3 did the Fed enter into a more open-ended asset buying program. The Fed’s forward guidance and policy of paying interest on reserves limited the transmission of QE to the broader economy. The Fed was concerned that low interest rates and the liquidity provided via QE would spill over into excessive inflation. These fears proved to be misplaced, with the United States recording some of the lowest rates of inflation in the post-World War Two period under QE. This indicates that the effective stance of monetary policy was too tight rather than too easy. Those who argue that QE was ineffective because of this subdued post-financial crisis inflation and growth performance are missing the more obvious conclusion that monetary policy was never particularly easy under QE. The empirical estimates of QE’s effectiveness in the United States between 2009 and 2014 should thus be viewed as a lower bound.

If implemented in Australia, QE could be much more potent by learning from the Fed’s mistakes. The main lesson for the Reserve Bank is that it should quickly transition from using the official cash rate to outright purchases of financial assets before the level of the nominal official interest rate becomes a constraint on the ability of monetary policy to stabilise nominal spending. The RBA should communicate, even before it needs to adopt QE, that the zero lower bound is not a constraint on the effectiveness of monetary policy. If the Australian government believes that monetary policy is constrained, it could pursue fiscal and other policy options that are ineffective in stabilising nominal spending.

If needed to support nominal spending, the RBA should enter into large and open-ended purchases of government and non-government debt and other securities and undertake to maintain those purchases until its macroeconomic stabilisation objectives are achieved. US experience suggests asset purchases of around 1.5 per cent of GDP are needed to deliver the equivalent of a 25 basis point reduction in official interest rates. However, asset purchases by the RBA could be more effective in stabilising nominal spending than those of the Fed to the extent that they are part of a more effective and more clearly communicated framework for policy. Australia could implement a smaller but more effective QE program than the US Fed between 2009 and 2014.