Executive summary

Technological disruption is rapidly changing the nature of work and the skills needed to succeed at work. It’s estimated that around half of current work activities can be automated by adapting currently available technologies. To address this disruption, governments must prepare future workforces for jobs that will require more digital and interpersonal skills and less repetitive skills susceptible to automation.

Three areas of focus are seen as the critical components to developing the future workforce:

- computer science education to develop digital skills;

- pathways to skilled work — most commonly apprenticeships — to develop post-secondary school specialisation and qualifications; and

- soft skills training — such as effective communication, social and emotional intelligence, critical thinking and adaptability — to develop the means by which to most effectively facilitate the digital skills and specialisations.

In the United States, workforce development is a bipartisan priority, key to the agenda of most state governors across the country. As Australia faces the challenge of an uncertain future of work, looking at the strategies of US states, where there are diverse examples of excellence driven by a different educational system, provides an opportunity to put lifelong learning into practice.

Computer science

The United States currently has more than 500,000 open computing jobs nationwide and yet only graduated 63,744 computer science students into the workforce in 2018.1 Demand for the broader group of ICT workers in Australia projects the current 660,000 will increase to 750,000 by 2023, and yet Australia graduates less than 5,000 ICT students annually,2 around one-third of creative arts graduates.3

The experience of the US state of Arkansas suggests more could be done. In addition to legislative and regulatory changes supporting computer science education among students, Arkansas has focused on teachers, creating new professional development pathways and removing obstacles to qualification, supporting marked growth in the number of computer science specialist teachers.

Apprenticeships

The middle skill job market — roles that require some post-secondary education or skills training, but not a university degree — is being hollowed out in the United States. Youth apprenticeships are a proven pathway for non-college bound young people to find middle-skill jobs in non-traditional often high-tech industries. Australia’s youth apprenticeship system is longstanding, more cohesively governed and attracts greater participation than in the United States, but remains overwhelmingly geared toward middle skill roles in traditional industries such as construction. It also does little to train workers for non-traditional growth industries. Washington and Colorado are two US states with youth apprenticeship opportunities in advanced manufacturing, IT, financial services, business operations and healthcare.

Soft skills

The automation of repetitive tasks has prompted focus on honing soft skills — those innately ‘human’ qualities like creativity, leadership, critical thinking and resilience. While this appears to be a second-order concern for US leaders, it has nonetheless spurred partnerships across half the states to implement social and emotional learning standards.

Australia has a sound platform for soft skills integration, through the General Capabilities at the heart of the Australian Curriculum. However, the challenge facing teachers and policymakers in both Australia and the United States is that there is no history of best practice to draw upon when teaching soft skills, nor are there well-established methods of testing them.

Recommendations for Australia

1. Increase digitally-skilled teachers, not just students

Developing a leading digitally-skilled workforce requires leading digitally-skilled teachers. Policymakers and academics need to work together to ensure university curricula delivers lifelong learning of computer science skills and training for teachers. As new teachers graduate from university, they should be fully equipped with the digital skills anticipated for the future of work. Professional development for existing teachers should look to reduce barriers to computer science upskilling and provide ongoing encouragement and support.

2. Expand apprenticeship principles to cutting-edge fields

Several US states are applying apprenticeship principles to new fields such as advanced manufacturing, cybersecurity, renewable energy technology and financial services. Australia should look to leverage its considerable apprenticeship policy strength and success into areas of emerging digital skills shortage to be ready for the future workplace.

3. Increase deliberate soft skills training

As advanced as computers and robots have become, there are still complex skills they cannot replicate at this point in time. Creative and critical thinking, social responsibility, communication, leadership and empathy are increasingly valued for the way in which they enable students to process information and come to conclusions. However, teaching and measuring soft skill proficiency and progression is in an exploratory phase. The United States, with its decentralised and more diverse schooling system provides great opportunity for Australian policymakers to examine a variety of approaches.

Introduction

In America, state governors meet twice a year to share strategies on issues facing their states. These National Governors Association (NGA) meetings bring together not only the governors, but also business leaders and community stakeholders to look at particular themes where there is broad opportunity or concern for the governors. Building on escalating gubernatorial attention to workforce and technology issues, the NGA Chair’s Initiatives of both current head Steve Bullock (D-MT) and his predecessor Brian Sandoval (R-NV) address technology and labour disruption challenges.4 Of the 46 governors who delivered “State of the State” speeches in 2018, 37 spoke on the topic of workforce development.5

Technological change drives this focus. Over the past decade, the capabilities of artificial intelligence (AI), robotics and machine learning technologies have escalated dramatically, as have their commercial applications. Intelligent chatbots handle customer enquiries for companies around the world. Autonomous trucks haul iron ore at mines in Western Australia. Countless individuals interact daily with AI, conversing with Amazon’s Alexa and the Google Assistant. The timeline for pervasive commercial adoption of such technologies is uncertain. Adoption depends on factors such as ease of commercialisation, cost (especially relative to labour costs), ease of use and legislative conditions.6 However, be it within the next decade or over the next several, this so-called ‘fourth industrial revolution’ will undoubtedly redefine the nature of work.7

The ideal future employee is emotionally and socially intelligent, digitally capable and formally qualified.

Exactly what this redefinition will look like is unknown, although most researchers agree that repetitive or routine tasks will increasingly become the domain of robots.8 This will engender some level of workforce displacement, most likely of lower-wage, so-called lower-skilled workers (such as accounting clerks, truck drivers and assembly line workers) whose roles heavily entail such tasks. For most professions automation is expected to result not in displacement, but in change or augmentation.

One expectation is that for about 60 per cent of occupations at least one-third of the constituent activities could become automated.9 This figure refers only to technical feasibility of automation, and not likelihood. However, the implication is that as machines increasingly conduct repetitive tasks, humans will spend more time managing technology and focusing on the unpredictable, creative and social dimensions of work.10

Such changes would necessitate a radical shift in the experiences, credentials and skills that young people need to succeed in the emerging workplace. So-called ‘soft’ skills — leadership, social and emotional intelligence, problem solving, adaptability and the like — are expected to prove vital in capturing automation-secure jobs, given that such skills presently remain beyond commercial AI.11 As technology becomes more pervasive in the workplace, digital skills are also likely to be at a premium. In Australia, more than 90 per cent of the current workforce is predicted to require at least basic digital literacy within the next 2-3 years, whilst around 60 per cent will need to at least be able to use and configure digital systems.12 The United States will face similarly high levels of digital skill demand,13 and in both countries such skills will be key in capitalising on the boom in information technology-related employment.14

More broadly, post-secondary education is likely to be an increasingly crucial prerequisite for sustainable, well-paid employment. As summarised by a 2018 OECD report, ‘higher educational attainment translates into a lower risk of automation’.15 With the exception of some so-called ‘low-skilled’ but unpredictable occupations — such as gardeners, or personal care workers — jobs that can be entered without formal education or technical training beyond high school are generally those most readily automated.16 With opportunities expected to shrink for those with a high school diploma or less, university degrees or vocational credentials — and the higher-order skills they are taken to represent — are seen as increasingly necessary for secure employment.17 In short, the ideal future employee is emotionally and socially intelligent, digitally capable and formally qualified.

These same changes, challenges and expectations face American and Australian youth. Noting US governors’ collective focus in this space, it seems fruitful to examine popular workforce development strategies championed at the US state level to advance young people’s digital skills, qualification levels and soft skills. In so doing, it may be possible to determine areas in which US and Australian states can learn from each other to develop policy that will prepare youth for the changing workplace.

The big ideas: Prominent state workforce development policies

In their 2018 “State of the State” speeches, the 37 governors of US states who spoke on workforce development included 81 per cent of Republican and 85 per cent of Democratic governors. Bipartisan recognition of the need to help prepare the future workforce for technological change manifests in the popularity of particular policies, and emerges despite deep ideological separation on prominent issues.

For instance, Arkansas’s Asa Hutchinson (R) welcomed US withdrawal from the Paris Climate Agreement,18 whilst Washington state’s Jay Inslee (D) responded to withdrawal by forming an alliance of governors pushing climate action.19 However, both have pledged millions of dollars toward improving computer science education, and collaborated to launch a ‘Governors for Computer Science’ partnership.20 This objective — expanding computer science education in schools — is the crux of gubernatorial efforts to equip young people with digital skills.

Similarly, Oregon’s Kate Brown (D) and South Carolina’s Henry McMaster (R) have driven diametrically-opposed policy responses to undocumented immigration.21 Yet both propose expanding youth work experience programs.22 Increasing opportunities for young people to complete workplace experiences — most notably, youth apprenticeship programs — is central in governors’ efforts to boost youth acquisition of post-high school skills and qualifications.

Rhetorically, governors do not focus on soft skills development to the degree that they do on expanding computer science education and youth apprenticeships. Yet whilst less prominent, governors are nevertheless taking action in this space, most notably through efforts to integrate critical thinking, creativity, social responsibility and related soft skills into classroom learning.

Area of focus 1: Expanding computer science education

Between 2009 and 2015, US employment in computing occupations grew by 21.9 per cent, and by 2024, is predicted to increase a further 12.5 per cent from 2014 levels.23 This would create nearly half a million new computing jobs across the United States, exacerbating huge existing demand for qualified workers. According to Code.org, a non-profit dedicated to expanding computer science (CS) access, the United States currently has around 500,000 unfilled computing jobs.24 As at November 2018, state-level demand for computing workers ranged from 2.6 times the state average demand rate in Vermont and Montana to 5.5 times the rate in Louisiana.25

Moreover, most sustainable future professions will require at least basic digital literacy. Somewhere between 65 and 82 per cent of existing US middle-skill jobs have been found to require digital competency.26

There is broad recognition among US governors that computer science, as articulated by former Wyoming Governor Matt Mead (R), ‘is as important a classroom subject as any’, and ‘a requisite for our students to become life-ready, workforce ready’.27

Within the last five years — buoyed by the increasingly global ‘computer science for all’ movement — governors have widely begun to prioritise computer science as an essential area of K-12 study. In 2016, eight governors launched the now 16-member bipartisan Governors for Computer Science partnership, through which they share best practices for expanding CS, and lobby for supportive federal policies and funding.28

US national context |

|

By 1991, 98 per cent of US schools possessed and used computers for instructional purposes.[^29] However, the quality of this instruction varied widely — as of 1996, the average ratio of students to computers across the United States was 10 to one.[^30] Whilst programming and AP Computer Science exams had been offered in some schools since the 1980s,[^31] computers were used mainly to assist traditional instruction. Through the 1990s and 2000s, Presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush enacted policies expanding classroom computer access and internet connectivity, but these policies continued to characterise the computer primarily as a supplementary tool, and computer science as a fringe, elective subject.[^32] Enthusiasm for CS education grew in the early 2000s, driven by the private sector. In 2003, the Association of Computing Machinery (ACM) released a Model Curriculum for K-12 Computer Science, which became something of a default template for CS implementation in the absence of any centralised national standard.[^33] In 2004, ACM drove formation of the Computer Science Teachers Association. Through the National Science Foundation, the Bush administration began rolling out student and teacher CS development programs in states such as Georgia and Massachusetts. However, only under Barack Obama did the federal government begin to meaningfully promote CS as an essential area of school study. Through speeches and symbolic actions like becoming the first president to write a line of code, Obama enshrined K-12 CS access as a national priority.[^34] This goal received bipartisan endorsement. However, Obama’s role was largely that of agenda-setter, as Congress blocked his US$4 billion proposal for realising this vision.[^35] In 2017, Donald Trump directed the Department of Education to reallocate at least US$200 million annually toward grants promoting STEM and CS, and elicited a matching US$300 million pledge from several major tech companies.[^36] |

Since 2013, 44 states have enacted policies supporting K-12 computer science, including through funding increases, curriculum changes or the creation of CS leadership positions within state education agencies.37 These actions build on private sector efforts such as Google’s CSFirst initiative,38 and non-profits like Girls Who Code, Black Girls Code and Code.org.39 These nationally active organisations host coding and computing programs introducing children to CS, with a particular focus on girls and children from minority groups underrepresented in the tech industry. However, many state initiatives remain detached from robust planning and funding, and national progress toward universal K-12 computer science remains nascent. As of 2016, CS was only offered in around a quarter of US high schools (mostly in affluent areas), and often only very rudimentarily.40 Nevertheless, select states are making substantive progress in expanding CS education.

Exemplar case: Arkansas

Arkansas has become a national pioneer in K-12 CS education under the leadership of Asa Hutchinson (R), whose pledge to expand computer science was central to his 2014 campaign for governor. In 2015, the state became the first in the nation to pass legislation — Act 187 — requiring all public high schools to offer at least one computer science course.41 Complementing this legislation, Arkansas established a comprehensive strategy for developing and implementing K-12 CS standards, in place since 2016.42

This legislation and strategy is part of a state vision to see ‘all Arkansas students actively engaging in a superior and appropriate computer science education’, with the intent that the state be ‘a national leader in computer science education and technology careers’.43 To this end, Hutchinson has driven extensive efforts to integrate CS into education. These include creating a new course (Essentials of Computer Programming) to be offered in state schools,44 and regulatory changes mandating that CS be allowed to count toward mathematics or science credit for graduating high school students. Arkansas was the 15th state to make this change,45 and is now one of 39 states that permit computer science to count.46

Equally as important as these curricular and regulatory measures is the political momentum Hutchinson has built behind realising universal CS access; in September 2018 he completed his seventh ‘computer science tour’ of state high schools, promoting the value of CS and encouraging students to enrol.47

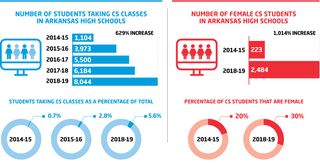

This cocktail of political momentum and curricular and regulatory changes seems to be producing positive results. In the 2015-16 school year — the first after passage of Act 187 — every public high school in the state offered at least one computer science course.48 Since then, the number of students sitting these classes has grown from less than one per cent to 5.6 per cent in 2018-19 (see infographic below), ensuring that the state’s goal of having 7,500 students enroled in CS classes was achieved one year ahead of schedule.49

Infographic: Arkansas changed the game in 2015 by legislating for computer science courses in all public high schools

Promisingly, Arkansas is also making progress in encouraging participation among populations underrepresented in IT, including increasing the proportion of females to 30 per cent of students.50 Strikingly, African-American female enrolments increased by more than 600 per cent in just the first year after passage of Act 187.51

A key ingredient in this rapid progress is the state’s robust investment in its more than 33,000 public school teachers.52 At Act 187’s passage in 2015, one of the state’s goals was to have a licensed computer science teacher in 95 per cent of public and charter high schools by 2020-21.53 At the time, there were only 20 fully qualified CS educators in Arkansas — a population clearly incapable of offering in-person instruction at all 305 public high schools in the state, let alone at its nearly 750 public elementary and middle schools.54 To overcome this shortfall the state offers schools free access to Virtual Arkansas — an online provider of CS classes. Alongside this resource, Hutchinson’s administration has devoted considerable attention and funding toward creating a pipeline of capable, certified teachers.

Accompanying Act 187, the state allocated an initial US$5 million to fund CS training for teachers and equipment acquisition for schools.55 Each year since, the state has allocated US$2.5 million toward teacher training, much of which has gone toward opening new pathways for professional development.56 In 2016 for instance, US$1 million was directed toward 15 different training programs, which by mid-2017 had been taken up by around 2,000 teachers.57 Over 2017 and 2018, Hutchinson allocated US$800,000 toward a ‘K-8 Computer Science Lead Teacher Training and Stipend Program’. This scheme subsidised 400 teachers to undergo a five-day training course, in which they not only learn to teach K-8 computer science but also learn to provide professional development to colleagues.58 Local universities are also offering teacher training, and in September 2018 Hutchinson launched a US$250,000 grant program through which public schools can gain reimbursement for professional development costs (among other expenses).59 Many of these efforts focus on upskilling in-service teachers. However, Hutchinson’s administration has also taken steps to expand recruitment of new computer science teachers, including by reimbursing assessment fees for individuals who successfully pass the state’s CS educator licensure exam.60

These efforts are bearing fruit. In addition to the thousands of teachers that have participated in more general professional development, Arkansas now has 372 qualified CS educators — 184 fully certified teachers, and 188 alternatively credentialed teachers (meaning individuals without a traditional education degree, but with qualifications in specialty subjects — in this case, computer science).61 This represents a 1,760 per cent increase from 2014, the year preceding Act 187. To further incentivise this progress, Hutchinson announced in September 2018 that all certified CS educators in Arkansas would have their state teacher license renewal waived, and would be provided with free membership to the national Computer Science Teacher Association. This membership provides discounted online professional development, support in gaining additional teaching certifications, and free teaching aids to use in the classroom.62

This comprehensive support for teachers is the defining feature of Arkansas’ approach to expanding student participation in CS. As Australian state and federal governments pursue similar goals, this is an area in which there may be room to improve.

Australian action

Australia is facing a supply and demand issue for IT skilled workers

As in the United States, Australia faces rising demand for IT workers, with predictions of an additional 100,000 jobs by 2023 and an average annual rate 1.6 times that of overall workforce growth.63 More broadly, an estimated 90 per cent of Australian jobs will require digital skills within the next five years and almost half will require workers to be able to ‘configure and use digital systems’.64

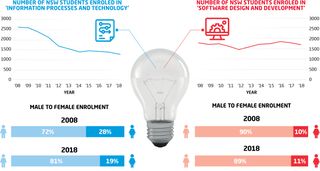

Problematically, young Australians’ participation in ICT has declined in recent years. University enrolments in IT degrees — although now rising rapidly — cratered throughout the 2000s following the dotcom crash, and remain well below peak 2002 levels.65 Meanwhile, Australia’s National Science Statement, released in 2017, noted that Grade 11 and 12 STEM subject enrolments were declining, and were at their lowest point in two decades.66 In NSW for instance, Higher School Certificate-level participation in ICT is low, especially among female students, and has plateaued for the last decade (see infographic below).

Infographic: In New South Wales, participation in HSC ICT subjects has plateaued or declined for the last decade, especially among female students

A national curriculum is a strength for Australia, but may inhibit experimentation

Australian politicians and policymakers have recognised these trends, and like their US counterparts, have stressed the need to expand and improve in-school ICT instruction.67 Crucially, Australian policymakers are acting to expand in-school ICT education, most notably through the national Foundation to 10 (F-10) Australian Curriculum.

This curriculum enshrines ICT Capability as one of the ‘General Capabilities’ — compulsory cross-subject development areas deemed essential for ‘young Australians to live and work successfully in the twenty-first century’.68 Building on this in 2015, Australia’s education ministers endorsed a national ‘Digital Technologies’ (DT) Curriculum. From F-9 (at which point students can undertake elective courses), the DT Curriculum sets out mandatory learning areas such as data analysis and representation, programming languages, and coding.69 The first cohort of students to study DT from Foundation year will begin school in 2019. According to Code.org, only six US states similarly provide access to CS for students from kindergarten to grade 10.70

Integration of ICT into the National Curriculum — both as a discrete subject and cross-curricular capability — speaks to a major advantage that Australia holds over the United States in strengthening computer science education. Broadly, governance of the Australian school system is a national affair. Although regulatory responsibilities primarily lie with the states, the federal government plays a crucial funding and agenda-setting role, and educational offerings across the states and territories exhibit only minor variations. By contrast, the United States lacks a national curriculum, and possesses a highly decentralised school system. Most responsibility for shaping educational standards and offerings is devolved to the state level, and in many cases to individual school districts. This structure limits standardised cross-state action, and there is considerable variation in educational content and quality between districts, let alone states.

To some degree this structure can support greater experimentation in schooling, and allow states and school districts to innovate in meeting challenges like CS access. In Arkansas, Governor Hutchinson was elected in 2015 and that same year engineered the legislative and curricular changes that underpin his state’s CS leadership. Were the governor more accountable to national educational directives and policymaking bodies, it seems unlikely that he would have been able to so rapidly implement such sweeping action. The flipside to this though is that a decentralised system innately leaves some states, and more importantly students, behind. For every Arkansas, there is a state like Maine that has no plan for implementing CS, does not allocate funding for relevant teacher training, and has a Department of Education that in 2017 opposed formalising CS as a more prominent part of schooling.71 Such are the consequences of an educational system that, on a spectrum of freedom to fairness, leans heavily toward the former.

The opposite is true in Australia. Absent the latitude of a decentralised structure, progress on ICT education in Australia is slow. Although development of the DT Curriculum began with a ‘Shaping Paper’ released in 2010,72 it was not until September 2015 — several Shaping Papers and close to an entire generation of high school students later — that the education ministers endorsed the Digital Technologies Curriculum, let alone began implementation.73 By the time the first cohort of students graduate that studied Digital Technologies from Foundation Year, it will be 2031. Yet whilst this sluggish progress is frustrating, it is also a testament to the depth with which experts and educators were consulted to develop a complex national curriculum that is well equipped to respond to technological change. Rather than focus on specific technologies, the DT Curriculum prioritises foundational computing concepts such as abstraction and computational thinking. Whilst it mandates instruction in programming languages, it is non-specific as to which must be taught, allowing space for content modernisation as technology evolves. This onus on teachers to progressively change their practices could be a source of risk. However, the curriculum itself is well positioned to be enduringly relevant. As a platform for improving the digital skills of all students, the DT Curriculum places Australia on much stronger foundations than the United States.

Breadth versus depth in computer science education |

|

A mandatory, nationwide Digital Technologies (DT) Curriculum seems to reflect a goal of breadth in Australian policymakers’ approach to CS education — i.e. one of ensuring that as many students as possible emerge from school with at least a moderate level of digital competency, even if they do not elect to study DT in senior years. This approach supports students’ collective employability, whilst addressing demand for digitally-skilled workers who can contribute to productivity across all sectors of an increasingly digitised economy. Breadth is also evident in President Obama’s flagship ‘Computer Science for All’ initiative announced in 2016 aimed at making students ‘job-ready on day one,’[^74] whilst the goals of the bipartisan Governors for CS partnership centre on universal and equal access to CS education.[^75] An alternative view argues ‘there are a finite number of students with both the interest and the talent to excel in computing and pursue high-paying computing careers’.[^76] In a world of limited resources, the ultimate goal of CS education policy should be ‘enabling a higher percentage of these students to acquire an in-depth education in computer science’ and go on to gain tertiary degrees in CS.[^77] This alternative strategy is one of depth, and prioritises developing the elite CS talent crucial in sustaining a nation’s high technology industries. Some American students can pursue depth in CS education through more than 100 math and science high schools — specialty schools in which students study more complex STEM subjects (including CS).[^78] Catering to those with pre-existing competency and interest in STEM, these schools tend to produce motivated and highly capable students likely to pursue tertiary STEM degrees.[^79] Investment in such schools supports the United States’ high-tech industries and technological edge — although such a strategy can provoke claims of elitism and ‘picking winners’.[^80] Australia also has technology schools: 24 in South Australia (linking STEM and employment in the defence industry), 10 in Victoria and 13 in NSW.[^81] Given the DT Curriculum strives to teach complex computational thinking over basic digital literacy or rudimentary technical skills, Australia seems well positioned to pursue both broad and deep CS education. If resources are available — which seems to be the case, given bipartisan support for robust CS education — there’s no reason these goals cannot be pursued complementarily. |

The success of Australia’s approach to increasing Digital Technologies capability rests on teachers, relying on them to skill themselves for success

Complemented by state schemes like NSW’s A$23 million ‘STEMShare Community’ program,82 federal policymakers have sponsored various initiatives supporting the DT Curriculum, and STEM participation broadly. Most notably, the 2015 National Innovation and Science Agenda (NISA) allocated A$51 million to initiatives in this area.83 Several of these initiatives offer teachers DT professional learning (PL) — most prominently, the A$10 million Australian Computing Academy (ACA) based at the University of Sydney,84 and the Computer Science Education Research (CSER) Group’s ‘Digital Technologies MOOC’ program, based at the University of Adelaide.85 The former hosts travelling in-person workshops orienting teachers in core DT concepts, whilst the latter performs a similar function via free online courses. Both initiatives are tailored to the curriculum, and in the case of CSER’s MOOCs, are highly accessible to teachers nationwide.86 However, several issues potentially limit their effectiveness.

The first is that the onus is on teachers to pursue these learning opportunities — on their own time for CSER MOOCs, and on their own dime for ACA workshops (A$100 per ticket). This voluntary system seems incongruous with the curriculum’s mandate that DT be compulsory, and ICT incorporated across all subject areas. A voluntary system means individuals may neglect training, perhaps due to a lack of confidence or overestimation of their own competency.

Whilst DT PL offerings are readily available to teachers, they must be ensured ample opportunity and incentives to pursue them. More than 90 per cent of NSW’s 18,000 public school teachers have indicated that rising administrative and reporting requirements are impeding their core job of teaching students.87

This could mean additional PL days, although this places a burden on schools to cover the cost of substitute teachers.88 According to the OECD, Australian teachers spend an average of four days per year at PL courses or workshops — half the average number for teachers across the 32 countries surveyed.89 Whereas annual PL requirements for Australian teachers range from five days in NSW to just 20 hours in several states,90 the minimum requirement in a basic Arkansas teacher’s contract is six days.91

Australia’s federally funded professional learning programs don’t remedy the nation’s undersupply of specialist computer science teachers.

Arkansas prioritises the funding of DT in PL, decreeing that ‘the first priority for the award of funds’ to teachers would be training undertaken in a small selection of fields, including Computer Science.92 State governments could also subsidise membership costs for state CS teacher associations. In NSW this would mean covering the A$70 annual cost of joining ICTENSW, a professional organisation for ICT educators. This association provides members with learning workshops, educational resources and discounted tickets to ACA programs, and enables teachers to connect and share DT approaches.93

The second and perhaps greater issue affecting government-sponsored training programs is that their focus is orientation level PL. For instance, the ACA’s workshops generally run for just two days, with the limited aim of building teachers’ confidence concerning basic DT concepts. This kind of introductory training seems particularly useful for primary school teachers, who instruct a single class of students across all subjects. However, it does little to train the specialist DT teachers needed to effectively implement the curriculum in secondary school, and who are crucial in equipping students with the skills and enthusiasm to undertake tertiary IT study. Unlike in Arkansas, where the growing number of certified CS educators reflects a focus on addressing this need, Australia’s federally funded PL programs don’t remedy the nation’s undersupply of specialist computer science teachers.

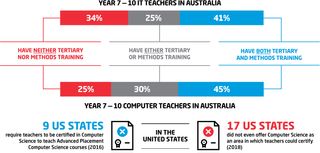

Australia and the United States have high proportions of ‘out-of-field’ ICT and computing teaching

The undersupply of specialist computer science teachers is evident in the degree to which ICT and computing classes are being taught by ‘out-of-field’ teachers. In Australia, around one third of Years 7-10 IT teachers are out-of-field — meaning they had not either studied the subject for at least one semester at university, or studied teaching methodology in that subject. Around 25 per cent of Computing teachers were similarly out-of-field, whilst the share of teachers that had not completed both relevant tertiary study and teaching methodology was around 60 per cent in both of these subjects (see infographic below).94 These figures do not account for non-DT specific teachers, who may lack digital training or expertise but — in the spirit of the Australian Curriculum — are expected to embed digital skills into traditional subjects areas.

Similar issues face the United States. Seventeen states do not even offer CS as a field in which teachers can certify,95 and as of 2016 only nine states required that teachers be certified in CS to teach advanced CS courses.96

Infographic: Many Australian and American ICT teachers are underqualified

There is a wealth of higher-paid employment opportunities available to IT specialists outside of teaching. However, in lieu of increasing pay for specialist DT teachers, universities could take action to address DT capability. For instance, universities could make DT a compulsory area of study for all teachers-in-training — if not at the level of a major, at least as a subject students must study for at least one semester. More generous government subsidies could be offered to university entrants who choose to specialise in IT, conditional on their teaching for a certain period after graduation. Subsidies and guarantees of favourable employment (such as permanent or ongoing contracts) could similarly incentivise IT specialists to gain teaching qualifications.

Area of focus 2: Expanding youth workplace experiences

Many US governors echo Kate Brown’s (D-OR) concern over ‘a gap between the skills Oregon’s workers have and the skills that our growing businesses need’.97 Specifically, many governors focus their concern on emerging shortages in middle skill roles — as explained by Rhode Island’s Gina Raimondo (D-RI), ‘70 per cent of jobs in Rhode Island require more training and education than just a high school diploma, but don’t all require a four-year degree’.98 Constituting more than half of current US employment, such roles are estimated to account for 40-55 per cent of job openings in every state.99

Many governors are taking action to instil young people with the requisite skills to fill these jobs — most prominently by increasing workplace experience offerings for school students. The logic behind this strategy is that such experiences can expose students to high-demand middle-skill opportunities, set them on a path to attain relevant post-secondary skills and credentials, and thereby create a talent pipeline of skilled workers from school to the workforce.100 The centrepiece of gubernatorial thinking in this space is the expansion of school-based youth apprenticeships — an idea that has undergone a contemporary renaissance in the United States.

US national context |

|

Established under the 1937 National Apprenticeship Act, registered apprenticeships are a longstanding feature of the US workforce training system. However, the federal government has generally held a minimal role in their management and funding, and enthusiasm for apprenticeships has historically fluctuated.[^101] This is particularly the case for registered youth apprenticeships. Youth apprenticeship programs differ from registered apprenticeship primarily in their focus on young people. In the United States, registered apprenticeship is primarily an adult training pathway, and participants usually commence in their mid to late 20s.[^102] Running anywhere from one to six years in duration, registered apprenticeship programs combine paid on-the-job training with classroom instruction, at the conclusion of which an apprentice earns an industry-recognised credential.[^103] Youth apprenticeship programs share this same basic formula, except that apprentices generally begin training in the final two years of school, and conclude after a maximum of four years (often much less).[^104] In response to widening inequality and the perceived threats of globalisation to American jobs, youth apprenticeships first drew meaningful federal attention as part of the ‘school-to-work’ (STW) movement of the late 1980s and early 1990s.[^105] George H. W. Bush and Bill Clinton pushed strongly for youth apprenticeships as a way to strengthen the skill levels and employment outcomes of non-college bound youth.[^106] This drive culminated in Bush’s unsuccessful proposal of the 1992 National Youth Apprenticeship Act, and bipartisan passage of the Clinton-driven School-to-Work Opportunities Act (STWOA) in 1994.[^107] Intended as a near US$2 billion federal investment in youth apprenticeships, STWOA was watered down in the face of political and legislative hurdles. Whilst it still allocated generous funding to states to expand school-to-work training, much of STWOA’s focus became job shadowing, career counselling and other less formal activities.[^108] Long before its 2001 expiration, federal momentum for youth apprenticeships had dissipated. Governors’ current support for youth apprenticeship mirrors a more recent spike in federal attention to youth workplace experiences, and apprenticeship broadly. The Obama administration built considerable national enthusiasm for apprenticeships. Despite failing to pass a US$2 billion proposal for growing the US apprenticeship system, Obama repeatedly stressed its expansion as a national priority, identifying apprenticeships as a vehicle for economic growth and upward individual mobility.[^109] President Obama directed some funding toward this vision, including US$60 million in 2016 ‘to support state strategies to expand apprenticeships’.[^110] President Trump has since increased funding, and established a taskforce charged with increasing US apprenticeship numbers by around 1,000 per cent within five years.[^111] Although US$200 million of Obama’s proposed US$2 billion spend specifically targeted youth programs,[^112] Obama’s and Trump’s efforts largely focused on registered apprenticeships broadly. Nevertheless, through his ‘Summer Opportunity Project’ and proposed US$5.5 billion ‘First Job’ fund, Obama made youth employment and skills training a major focus of his administration.[^113] In the Trump era, Congress has since approved funding increases for apprenticeship programs and youth skills training — respectively, through the 2018 Omnibus Appropriations Act, and bipartisan Strengthening Career and Technical Education for the 21st Century Act.[^114] |

Amidst the national ‘school-to-work’ (STW) movement and drawing inspiration from European models, 20 states inaugurated youth apprenticeship programs between 1990 and 1992, including Maine, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania and Arkansas.115 However, as the movement fizzled over the 1990s, only a handful of these programs meaningfully survived this period.

Two programs that still endure are those of Wisconsin and Georgia. Wisconsin launched the United States’ first registered youth apprenticeship system in 1991, followed by Georgia in 1994. Targeting students in the final two years of high school, these programs blended classroom instruction with paid on-the-job training at local businesses, emphasising the value of ‘contextual, real-world learning’.116

This focus remains unchanged today, as does both programs’ essential structure. Classroom learning is combined with 450-900 hours of paid on-the-job training in Wisconsin, and 2,000 hours in Georgia, whilst participants in both states graduate with a high school diploma and industry-recognised certificate.117 At launch, Georgia’s youth apprenticeship program was in just 24 of the state’s 195 school systems.118 As of April 2015 this number had reached 143,119 and at present the state spends around US$3 million annually to support more than 7,000 apprentices.120 Similarly, Wisconsin’s program began with just 21 students placed at a single printing company.121 In the 2017-18 financial year, the state spent US$3.9 million funding 4,362 youth apprentices, placed across more than 3,100 businesses in sectors such as health care, construction, manufacturing, agriculture, energy resources and IT.122

These programs appear to be functioning quite effectively. More than 95 per cent of participating employers in Georgia reported benefit for their business from hosting an apprentice, indicating strong private sector satisfaction with the system.123 Meanwhile, Wisconsin’s system appears to be successfully transitioning youth from school to the workforce — 84 per cent of participants completed the program in 2015-16,124 and 60 per cent of graduated apprentices are offered jobs by the businesses at which they trained.125

Yet despite their apparent promise, neither of these programs have had significant impact in relative terms. Despite student participation in Wisconsin more than doubling since 2010 (employer participation has also almost tripled),126 the 4,362 youth apprentices participating in the program over the 2017-18 school year represented just 3.3 per cent of Grade 11 and 12 students in the state.127 This share is even smaller in Georgia, where its approximately 7,000 apprentices amounted to only 2.9 per cent of students in the final two years of high school in 2017-18.128 Whilst impressive in absolute terms, even these most successful of US youth apprenticeship programs are limited in a relative sense. These two programs are exceptions in the US workforce development landscape, rather than the norm.

Youth apprenticeships have never truly taken off in the United States, as nearly all involved stakeholders have been persistently reluctant to commit to the concept. Since the School-to-Work movement’s decline, policymakers have largely prioritised raising academic standards and college preparedness.129 Employers — unfamiliar with the return on investment that often comes with training apprentices — have historically been put off by high initial costs and fears of employee poaching.130 Broadly, youth apprenticeship is also a culturally unfamiliar concept. In the United States, a college degree has long been identified as the preeminent ticket to socioeconomic mobility and a sustainable career.131 Even as its security has broken down, many parents remain reluctant to encourage their children’s diversion from this proven pathway.132 Historically, some parents have also feared that youth apprenticeships will subject children to ‘tracking’, whereby students that perform poorly in earlier years of school are prematurely funnelled toward non-college pathways, and second-class jobs.133

The US higher education system is also far more generously subsidised than vocational alternatives. In the 2019 budget, Congress approved US$27.4 billion in discretionary funding for post-secondary education, yet appropriated only US$1.27 billion for Career and Technical Education (CTE) (see infographic below).134 This disparity has long endured, the result being that students are more likely to encounter better-funded and more diverse programs, services and amenities at four-year colleges than they would if taking vocational routes.

Infographic: US federal government funding for college education is far more generous than it is for career and technical education

Non-traditional youth apprenticeships: A key to future training?

In spite of these cultural and financial obstacles, youth apprenticeship is experiencing a renaissance in several US states, including Kentucky, Illinois and Maryland.135 Programs have also gained traction in North and South Carolina, driven by Siemens and other German employers seeking to adapt Germany’s successful youth apprenticeship model to the United States.136 Broadly, policymakers in these states are advocating the applicability of apprenticeships to high-tech non-traditional sectors, taking an innovative approach to youth apprenticeship more narrowly tailored to high-growth future industries. One exemplar program is Governor Jay Inslee’s (D-WA) ‘Career Connect Washington’.

Launched in June 2017, this initiative aims to connect ‘100,000 students during the next five years with career-connected learning opportunities that prepare them for high-demand, high-wage jobs’.137 At the heart of this drive is expansion of youth apprenticeship and pre-apprenticeship opportunities — an objective toward which Inslee’s administration is partly utilising a US$6.4 million federal grant, with the intent of sponsoring 1,400 positions.138 With a fairly standard structure — classroom instruction and paid on-the-job training, at the end of which participants earn a high school diploma and industry-recognised certificate139 — this program stands out for being future-facing and industry-targeting. Focusing largely on STEM-related professions, the initiative is creating apprenticeship opportunities in high-tech, high-growth sectors such as advanced manufacturing, renewable energy technology, aerospace and IT.

A similar approach underpins former Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper’s (D) ‘Careerwise’ initiative, a three-year youth apprenticeship program that combines classroom education, on-the-job training and college level coursework. Launched in 2016 and supported by federal, state and private funding, this program aims to see 20,000 youths enter apprenticeships by 2027.140 This program welcomed 126 students in July 2018 (its second cohort), who were placed with a roster of employers presently totalling more than 75.141 Again, it is this initiative’s sectoral targeting strategy that is of greatest interest. As remarked by Hickenlooper, Careerwise does not offer ‘your grandparents’ version of apprenticeship’.142 As in Washington, the program is streamlined to fields with high-growth potential: advanced manufacturing, IT, financial services, business operations, and healthcare.

Lessons for Australia

Due to the relative strength of Australia’s apprenticeship and broader vocational education and training (VET) systems, at first glance it seems that Australian policymakers can learn little from US youth apprenticeship programs.

As of March 2018, there were more than 272,000 apprentices training in Australia.143 Only around 20,000 of these are in-school apprentices, who combine part-time paid on-the-job training with regular in-school study.144 However, 68 per cent of Australia’s apprentices are aged 24 or less (including 35 per cent below the age of 20).145 This is a key difference to the United States, where less than a quarter of registered apprentices are under the age of 25.146 This disparity testifies to the scant links between US schools and apprenticeship systems, reflecting an entrenched cultural prioritisation of college over technical education. Some Australian commentators identify a similar stigma around apprenticeships and VET.147 On the whole however, Australia’s apprenticeship system bears strong connections to secondary education.

In the United States, the federal Department of Labor technically oversees registered apprenticeships. However, regulation and administration of apprenticeships is overwhelmingly decentralised to states. This can lead to wide interstate variances in training quality and management. Although the governance structure of Australian and American apprenticeship is formally similar, Australian federal leadership is more profound, federal-state coordination is far stronger, training standards are more uniform across states and most apprenticeship qualifications are nationally recognised, enabling workforce mobility. Similarly, whilst state and federal governments in both countries offer financial incentives for companies to hire apprentices, these incentives are more comprehensive and readily accessible in Australia, despite being tightened in recent years.

This is not to say that Australia’s apprenticeship system does not face challenges, even relative to the United States. Most notably, participation is falling. Since 2012, the number of US registered apprentices has grown by 47 per cent, increasing annually to more than 530,000 as of 2017.148 Over the same period, Australia has experienced continuous decline in apprenticeship participation, due largely to a dramatic decrease in traineeship enrolments after the federal government tightened employer incentives.149 Since annual apprenticeship commencements peaked at more than 375,000 in 2012, they have now fallen to less than 45 per cent of that figure, and as of 2018 sit at their lowest point since 1998.150

Nevertheless, even this comparison principally serves to highlight the relative weakness of the US apprenticeship system. According to the World Bank and International Labour Organization, apprentices constituted around 3.7 per cent of Australia’s workforce in 2011. In the United States, they made up only 0.3 per cent.151 Although apprentices now constitute only 2.2 per cent of Australian employees, in the United States the share remains the same at 0.3 per cent.152 On top of its other advantages, this relative workforce penetration level suggests that Australia’s apprenticeship system should serve as a model for the United States, and not vice-versa.

Australia can do more to align the apprenticeship system with future skills needs

As technological advancement changes workplace requirements and stokes the emergence of new industries, Australia’s apprenticeship system isn’t shifting accordingly. Historically, periodic efforts have been made to expand the range of sectors catered to by the apprenticeship model. The most notable was creation of traineeships in 1985 — a shorter variant of apprenticeship that primarily serves the retail, hospitality, and personal care sectors.153 However, as it has done for all of its modern history, Australia’s apprenticeship system remains primarily focused on traditional trades — automotive repair, commercial cooking, plumbing, electrical and most notably, construction. As of March 2018, more than one-fifth (21 per cent) of Australian apprentices were employed in construction alone.154 This high concentration is to be expected, given apprenticeships have historically been a preeminent training pathway in this sector. Moreover, amidst a boom in construction, employment in the sector grew by 17.3 per cent in the five years to November 2018.155 In line with this, the number of apprentices in construction also climbed, growing 25 per cent in four years.156

Australia faces a persistent shortage of skilled construction workers and tradespeople, especially in states like New South Wales and Victoria with extensive public infrastructure agendas and (perhaps until recently) booming housing industries.157 Moreover, whilst employment of some specific construction trades workers — such as bricklayers and stonemasons — is predicted to decline in the five years from 2018, employment of construction trades workers as a whole is expected to increase by 6.5 per cent by 2023.158

In the longer term, workers in construction and other trades feature in some forecasts of occupations at risk of automation. According to the OECD, ‘building and related trades worker’ jobs face a 52 per cent mean probability of being automated (although a timeline for any such displacement is not clarified).159 This probability increases for more general labourers in the sector. It seems unrealistic to suggest that a traditionally trained 18-year-old apprentice bricklayer will manage even half a career before a robot can do much of their job faster, cheaper, safer and with greater precision. Although far from widespread commercial adoption, such robots already exist and are developing rapidly.160

The problem is not that Australia’s apprenticeship system continues to train traditional tradespeople, but that unlike emerging programs in Washington and Colorado, it doesn’t do enough to also train workers in high-tech or high-growth non-traditional industries.

In 2018, 27,405 Australians began apprenticeships as ‘Community and Personal Service Workers’; a group that includes difficult-to-automate jobs like personal, aged and disabled care workers.161 Although accounting for the largest share of commencing apprentices by occupation group, this figure is a 30 per cent decline relative to 2014 — a worrying trend given Australia’s rapidly aging population. By 2023, projections indicate Australia will require an additional 230,300 community and personal service workers. This represents an increase of 17.5 per cent on 2018 levels, and encompasses employment growth of 27.4 per cent for ‘Personal Carers and Assistants’ and 39.3 per cent for ‘Aged and Disabled Carers’.162

Clearly, there is a critical imbalance in Australia’s apprenticeship system: whilst continuing to funnel youth into traditional trades, it has little role in training young workers for high-tech, high-growth middle-skill jobs.

A similar pattern applies to IT. In March 2018, just 3,030 apprentices — one per cent of the national total — were employed as ‘Engineering, ICT and Science Technicians’.163 This represents a 66 per cent decline since 2014 — despite the fact that demand for such workers is rapidly trending in the opposite direction. Australia’s ICT workforce needs are predicted to grow by almost 100,000 by 2023, including almost 42,000 workers in ICT trades or technical and professional roles.164 Similarly, the federal Department of Jobs and Small Business projects 7.1 per cent employment growth for engineering, ICT and science technicians by 2023 — including 17.5 per cent growth for ‘ICT and Telecommunications Technicians’ and 18.5 per cent growth for ‘ICT Support Technicians’.165 Australian universities currently produce only around 5,500 IT graduates annually (including 1,500 postgraduates) — clearly not enough to meet this huge projected demand.166 Apprenticeships could be an effective alternative training pathway, but remain heavily underutilised.

Clearly, there is a critical imbalance in Australia’s apprenticeship system: whilst continuing to funnel youth into traditional trades, it has little role in training young workers for high-tech, high-growth middle-skill jobs.

The federal ‘Industry 4.0 Taskforce’, which convenes industry and education leaders in part to strategise on meeting future education and training needs,167 has produced two federally funded, privately overseen ‘Higher Apprenticeship’ pilot programs — one in advanced manufacturing and the other in business, IT and professional services.168 However, these programs are very exploratory, and small in scale: the first is training just 20 apprentices at a single employer, and the latter intends to train about 250. This collective total is equivalent to a mere 0.001 per cent of Australia’s apprentices. Clearly, there is abundant scope to accelerate the development of high-tech, non-traditional apprenticeship in Australia.

In the meantime, Australian policymakers are leaning further into traditional apprenticeship models. For instance, in the 2018 New South Wales Budget, Premier Gladys Berejikilian announced an A$285 million plan to sponsor 100,000 fee-free apprenticeships over the next four years — the centrepiece of her government’s efforts to ensure ‘a strong pipeline of skilled workers across the state’.169 This plan explicitly complements the government’s pledged A$80 billion investment in infrastructure construction over the same period, meaning that those apprentices sponsored will predominantly be traditional manual trades workers — in the government’s own words, the scheme is designed ‘to capitalise on our record infrastructure program by creating the electricians, plumbers and mechanics NSW needs’.170

In the short term, this plan should help assuage the state’s shortage of construction trade workers,171 whilst helping create the workforce needed to sustain the government’s ambitious 20-year infrastructure investment strategy.172 However, any infrastructure boom is impermanent. Whilst there is certainly a need to balance present and future demand, the long-term wisdom of so heavily funnelling youth into these sectors seems questionable. Moreover, the government’s plan — and the language they use to market it — betrays a limited imagination regarding the potential of apprenticeships. Gleaning insight from the future-facing examples of Washington and Colorado, there is space for Australian governments to diversify the industries to which the system caters, and make greater efforts to funnel youth into higher-tech higher-growth fields that promise sustainable middle-skill employment in the digital age.173

Area of focus 3: Expanding ‘soft’ skills education in schools

The first two sections of this report examined efforts to equip young people with ‘hard’ skills — technical capabilities and qualifications that can boost students’ employability in the changing workplace. However, such hard skills are but one aspect of the future workforce-training picture.

As machines grow increasingly capable of performing the repetitive or routine aspects of work, most researchers concur that workers will spend a shrinking amount of time on these kinds of tasks. The timeline for this pervasive task transfer is unclear, as many factors other than technical feasibility affect the rate at which businesses automate. This phenomenon creates a displacement risk for various low-wage workers, for whom automatable tasks often constitute a greater share of job duties. More broadly though, it is likely to drive a shift in the skills that workers depend upon in the workplace.

Regardless of skill level or industry, most researchers concur that workers will spend an increasing share of time relying on innately human qualities, which presently lie beyond the capabilities of technology. Variously referred to as ‘soft’, ‘enterprise’ or ‘evergreen’ skills, these traits include social and emotional intelligence, communication, adaptability, teamwork, critical thinking, creativity, leadership and problem solving.

These qualities are the subject of much present hype. Predictions they ‘will become more than twice as important by 2040’,174 or defining soft skills as the ‘emerging skills’ needed by employees175 seem somewhat excessive, in that employers have surely long valued teamwork, creativity, leadership and other such traits. However, there is evidence to suggest that some employers are placing an increasing premium on these skills.

The case for soft skills

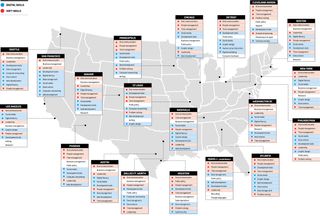

Increasing demand exists among Australian employers for various soft skills in early career online job advertisements — most notably critical thinking, for which demand grew by more than 158 per cent.176 Employer surveys have found similarly high demand for such qualities in the United States177 and globally,178 whilst research from the Foundation for Young Australians (FYA) and LinkedIn suggests that some Australian and US employers are valuing prospective workers’ soft skills at least as much as their hard, technical qualifications.179 One illustrative example is Google, which in 2013 conducted a study to determine the qualities that define its most successful managers. The top seven qualities identified were soft skills, and the company subsequently amended its hiring practices to place increased weight on these characteristics.180 More broadly, the infographic below illustrates the skills gap in the 20 biggest metropolitan areas in the United States. In almost all locations 40 to 50 per cent of the skills in high demand not being met are soft skills and for just more than half the locations 40 per cent or more of the skills in demand not being met are digital skills.

Infographic: Top skills shortages in 20 of the largest metropolitan areas in the United States: Mismatch between the skills US employers need (demand) and the skills workers have (supply) (View this as a PDF)

This is not to say that soft skills have not long been an important differentiator in hiring decisions, or that employers do not still value hard skills. Common sense suggests that the opposite is true. For example, a jobseeker could be boundlessly creative and a terrific team worker, but without advanced digital skills would certainly struggle to gain employment as a computer programmer. As Australia’s Chief Scientist Alan Finkel quipped in defence of the continued importance of specialist knowledge, an employer ‘will go badly astray if you pick ten people who collectively specialise in nothing at all’.181 Ultimately, the most successful employees of the future will complement deep technical capabilities with advanced soft skills.

The limited US experience with soft skills training

For US policymakers, soft skill development seems most often considered as a by-product of STEM and computer science study. For example, in December 2018 the Trump administration released a strategy to strengthen STEM education, which contends that participation in STEM subjects inherently builds problem solving, critical thinking, adaptability and perseverance.182 Similarly, in October 2018 New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy announced a ‘Computer Science for All’ initiative, which aims to equip students ‘with the critical thinking and problem-solving skills they need to think about the world in new and creative ways’.183

One prominent action was integration of ‘higher-order thinking’ skills into the Common Core State Standards (CCSS).184 Developed by the National Governors Association and championed by the Obama administration, the CCSS stake out content and capabilities that American students should learn from K-12 in English language and literacy, and mathematics. Although competency in these subjects is clearly the first priority of these standards, threaded throughout is a focus on teaching in ways that develop students’ collaborative, communication, creative and critical thinking skills. Since their 2010 launch, 41 states have implemented these standards.185

Various states have more explicitly committed to integrating soft skills into schooling. For example, in 2012, Kansas became the first state to adopt and implement social, emotional and character development standards for K-12 students.186 In 2018, Indiana passed a bipartisan bill decreeing that by mid-2019, each state public school must include ‘interdisciplinary employability skills’ in the school curriculum including work values and basic employment concepts.187 More broadly, the non-profit ‘Partnership for 21st Century Learning’ (P21) recognises 21 states as having developed plans ‘to embed 21st century learning (i.e. soft skills) within standards, assessments and professional development programs’.188 Similarly, 25 states have partnered with the non-profit Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning, working to develop social and emotional learning (SEL) standards.189

Similar action is occurring across the United States. For instance, the non-profit P21 identifies 95 exemplar schools and districts that innovatively integrate skills like problem solving and collaboration into traditional subjects.190 One example is a Californian school in which fifth graders were tasked with designing a playground for kindergarten students that would facilitate learning.191 This activity required students to draw on knowledge from science class, whilst utilising communication techniques learned from cooperatively building Lego sculptures. Other schools have conducted similar exercises, focusing on problem solving, collaboration and social responsibility.192

These initiatives evidence an emerging state-level focus on soft skills. However, they once more speak to the fragmented nature of the US education system. As with computer science education and youth apprenticeship programs, Australia’s centralised education system has enabled a more unified national approach to expanding the place of soft skills in schools.

US national context |

|

Soft skills education has gained only very limited direct support at the national level. Under President Obama, the Department of Labor developed a ‘Skills to Pay the Bills’ Curriculum in 2012 for use by youth development professionals.[^193] This aimed at teaching young people six key interpersonal and workplace readiness skills: communication, enthusiasm and attitude, teamwork, networking, problem solving and critical thinking, and professionalism. The Obama administration’s Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) education reforms, passed in 2015, also included the implementation of federal frameworks supporting Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) — some aspects of which support soft skills development. Although the actual ESSA legislation does not specifically mention SEL, it provides avenues through which educators and policymakers can source funding and resources for SEL-related programming.[^194] Since taking office in 2017, all three Trump administration budgets have proposed large-scale cuts to education, which would have eliminated key ESSA pathways through which schools can gain funding and support for SEL-related programming. However, Congress has consistently resisted such cuts, a trend almost certain to continue with Democrats now controlling the House of Representatives.[^195] Beyond the administration proper, First Lady Melania Trump’s ‘Be Best’ campaign perhaps shows some positive appreciation of SEL. Whilst diversely focused on promoting online safety and combating opioid abuse, this campaign broadly promotes youth well-being, stressing the need to ‘teach children the importance of social and self-awareness, positive relationship skills, and responsible decision-making’.[^196] To this end, in 2018 the Department of Education awarded a federal grant for a ‘Center to Improve Social and Emotional Learning and School Safety’, intended to help states and school districts implement SEL programs and practices.[^197] However, funding for this scheme is just US$1 million annually over five years, and the First Lady’s sentiments seem clearly at odds with the administration’s repeated attempts to cut funding for programs designed to meet the outcomes she advocates for. |

The limited Australian experience with soft skills training

Australian policymakers are not uniformly supportive of soft skills education. Whilst figures like NSW Department of Education Secretary Mark Scott have committed to equipping students with qualities like collaboration, creative thinking and resilience,198 others, like federal Education Minister Dan Tehan, have pushed back on the prominence of ‘soft skills’, stressing a need to reprioritise fundamentals like reading, writing and mathematics.199

Nevertheless, decades of reviews of Australia’s education system have consistently recommended that schooling should do more to promote problem solving, critical thinking, social skills and similar general qualities.200 These recommendations have been realised in development of the Australian Curriculum — specifically, the interdisciplinary General Capabilities at its heart. Of the seven General Capabilities deemed essential for ‘young Australians to live and work successfully in the twenty-first century’, four are soft skills: critical and creative thinking, personal and social capability, ethical understanding and intercultural understanding.201 For each of these, the Curriculum establishes ideal development benchmarks for students at each year level.

The challenge for schools and state education authorities is to ensure that General Capabilities are being taught and assessed effectively. Diverse action is occurring in this space. For example, the Australian Council for Educational Research’s Centre for Assessment Reform and Innovation (CARI) is developing an ‘assessment framework’ that can help teachers monitor and measure students’ competency in the General Capabilities. In trial across select Australian schools, this framework encompasses a set of problem-based assessment tasks, one of which entails Year 8 students planning how refugees can best be resettled in their community.202 This activity requires students to demonstrate creativity, collaboration and critical thinking, whilst engaging with real-world social issues. Similarly, Victoria University’s Mitchell Institute is working with 11 Victorian schools to trial methods of teaching the General Capabilities,203 whilst individual teachers and schools are creating activities, evaluation methods and interdisciplinary classes aimed at growing students’ soft skills.204

Best practice for soft skills training

In both the United States and Australia, integration of soft skills into schooling is still in an exploratory phase. Much of this space is uncharted territory, and there is little clarity among policymakers and educators as to how soft skill development should look in practice. US states and school districts are well positioned to test new approaches to this challenge, given the greater latitude for innovation inherent to the decentralised US education system. However, for many teachers in both countries, this new imperative demands unfamiliar styles of instruction. The NSW Department of Education offers various professional learning courses on critical and creative thinking, which to some degree can help the state’s teachers meet this challenge. Yet unlike traditional subject areas, there is no longstanding history of best practice to offer guidance in this area. Broadly, project-based learning is firming as a valuable and widely favoured approach in both Australia and the United States. However, there is not yet a concretely identified ‘silver bullet’ strategy for teaching creativity, collaboration and the like.

In both the United States and Australia, there is little clarity among policymakers and educators as to how soft skill development should look in practice.

Connectedly, there is no consensus when it comes to best practice for measuring soft skill progression. At the macro level, the OECD’s triennial Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) survey offers some indicators of students’ soft skill performance. The 2012 edition of this survey tested the creative problem solving skills of 15-year-olds,205 whilst the 2015 edition tested collaborative problem solving skills.206 In both cases, Australian students outscored their US counterparts (significantly so in 2012), and both nations’ results were above the OECD average. However, at an immediate in-school level there is no broadly recognised means of rigorously measuring students’ soft skill proficiency, and traditional assessment models are ill-suited. Whereas a quantitative grade can accurately reflect a student’s level of proficiency in algebra, for example, it would be largely meaningless as a reflection of their communicative or creative ability. In August 2016, the NSW Education and Standards Authority launched a pilot critical thinking exam for Year 11 students.207 This optional test consisted of 60 multiple-choice problems, and provided feedback on students’ analytical and logical reasoning skills relative to peers.208 Although now discontinued, this trial will inform the ongoing review of the NSW Curriculum (the state-level implementation of the Australian Curriculum). This review — the first in 20 years — could thus result in greater integration of soft skill development into education in NSW. As insights emerge from such trials and more and more schools try out different ways to teach and test soft skills, the primary challenge for American and Australian policymakers will be to identify best practices and metrics, and magnify their scale to the state and national level.