Executive summary

In times of economic crisis, the resilience of business is tested, often in unprecedented ways. There are always winners and losers. Right now, the United States is headed for astonishing levels of unemployment due to the economic shock of COVID-19. Nearly ten million Americans had filed for weekly unemployment benefits by the end of March, up from around 220,000 per week in the first two months of 2020. Estimates put this at an unemployment rate of around 13 per cent.1 More concerning is that following the United States’ Great Recession triggered by the global financial crisis, it took seven years for employment numbers to recover.

However, in previous US downturns, rates of entrepreneurship have risen alongside rising unemployment rates. Successful new ventures tend to have radically innovative products serving emerging market sectors. Successful businesses often have high-growth potential and a global perspective. Sectors doing well immediately in this current crisis include staple goods, food delivery, health and medical services and products. The emerging market of digital products that bring connectivity, entertainment, information and exercise directly to those staying at home are seeing strong growth.

Growing new ventures to a global scale is vitally important for the development of Australia’s entrepreneurial ecosystems.

While this research reflects the situation before COVID-19, it raises important questions about how Australians perceive and approach entrepreneurship, which will be critically important over the next months as the world faces into a global economic crisis.

Growing new ventures to a global scale is vitally important for the development of Australia’s entrepreneurial ecosystems. Australia has a very high proportion of small businesses, but both entrepreneurial activity and attitudes lag the United States.

Australians are about half as likely as Americans to be in the process of starting a business, less likely to know someone who has started a business in the last two years, less likely to identify business opportunities and, when a profitable opportunity is spotted, Australians are less likely to act on it than Americans.2

Additionally, despite the World Bank rating Australia as a very easy place to start a business — one of the top ten countries globally — only around two-thirds of Australians think this is the case. The relatively more challenging American business start conditions are not perceived that way with more than 70 per cent indicating it is easy to start a business.3

Prior to the COVID-19 crisis — and despite 28 years of economic growth — Australians were more anxious than Americans about a) losing their job or business, b) failure at work and c) losing everything and having to start from scratch. And while this anxiety decreased for high-income Americans, there is very little difference between high and middle-income Australians for these issues.4 Given more than a million Australians have just lost their jobs or businesses, kick-starting entrepreneurial thinking will be critical to overcoming the reality of COVID-19 impact on the economy.

Successful new ventures build networks and provide positive feedback of experience and capital that raise the quality and scale of entrepreneurship. The tech entrepreneurial ecosystem in Australia is already rising to this challenge. These companies and those that lead them become both the exemplars and the mentors for the next generation of entrepreneurs. There is no real substitute for this role of successful pioneers. Such pioneer entrepreneurs who remain active as mentors and angels are the key mechanism for the transformation of the Australian innovation system.

As Australia emerges from the immediacy of the COVID-19 crisis, building a culture that encourages and celebrates entrepreneurship is key. The eight companies highlighted as case studies in this report should serve as role models for other companies looking for US expansion.

The experience of these entrepreneurs suggests several insights that will be useful for other Australian ventures:

- Be prepared — but at the same time, there is no substitute for learning on the ground.

- Be proactive in building networks — for marketing as well as personal and professional support.

- Be informed about the many sources of advice and support that can complement your drive, focus and resilience.

- Be an insider. Locating some business processes in the United States and establishing a subsidiary or in some cases, a US headquarters may be preferable.

- Be aware that cities other than San Francisco or New York may be more appropriate for building your venture.

Australian start-ups scaling into the US market

The United States has long offered opportunities for Australian entrepreneurs and professionals. Close to 100,000 Australians are living in the United States, almost half of whom have tertiary or advanced research qualifications.5 There are estimated to be at least 20,000 Australians working in the San Francisco area.6 Over the past ten years at least 100 Australian start-ups have entered and built sustainable businesses in the US market. Many — like Atlassian, 99designs and Deputy — have been immensely successful.7

Growth-oriented Australian start-ups with a global perspective from the outset must direct scarce time and resources to engage with offshore customers and networks at a relatively early stage in their growth. This will be an uphill battle for some firms and managers as many lack experience developing and marketing innovative products and services for overseas customers and markets. COVID-19 will present a hurdle for some and an opportunity for others.

While the world is currently in a state of uncertainty, the 2018 Startup Muster report suggests, based on a survey of Australian start-up founders, that while increasing sales domestically was the top immediate priority, increasing sales outside Australia was the top priority beyond the next 12 months.8 Raising capital outside Australia was a significant priority for almost 30 per cent of the ventures over the next 12 months and beyond — however, raising capital from within Australia was a more important priority for most.9 If history is anything to go by, raising capital following a major economic downturn becomes very difficult. Following the DotCom crash, venture capital investment bottomed out in Q3 2002 and didn’t start to pick up until Q2 2003. Following the global financial crisis, Q1 2009 was the lowest point for venture capital investment, picking up again in Q3 2009.10

The best places to start a business in the United States

While it is too early to see the impact of economic stimulus in the wake of COVID-19, the ecosystem for business in the United States can vary widely from state to state. Beyond geography and population, the differences in taxation and incentives can be markedly different. Rankings of a range of factors to determine the best states in which to do business are published by several organisations. However, many of the factors analysed may be of more or less importance to Australian companies looking to enter the United States so are worth examining in detail.

Looking at six factors that indicate growth across the largest metropolitan statistical areas in the United States: job creation, population growth, net business creation, rate of entrepreneurship, wage growth and high-growth company density; the 20 best places for starting a business are set out in Table 1. These locations match up closely with LinkedIn’s Workforce report for February 2020, which sets out the US cities gaining the most workers in the previous month as determined by changes in members’ LinkedIn profile locations.

Table 1. Best cities for starting a business in the United States

|

Rank |

Best city to start a business |

State/territory |

US cities gaining workers |

|

1 |

Austin |

Texas |

1 |

|

2 |

Salt Lake City |

Utah |

|

|

3 |

Raleigh |

North Carolina |

8 |

|

4 |

Nashville |

Tennessee |

2 |

|

5 |

San Francisco |

California |

|

|

6 |

San Jose |

California |

|

|

7 |

San Diego |

California |

|

|

8 |

Denver |

Colorado |

4 |

|

9 |

Orlando |

Florida |

|

|

10 |

Portland |

Oregon |

10 |

|

11 |

Phoenix |

Arizona |

7 |

|

12 |

Seattle |

Washington |

5 |

|

13 |

Miami |

Florida |

|

|

14 |

Jacksonville |

Florida |

|

|

15 |

Boston |

Massachusetts |

|

|

16 |

Los Angeles |

California |

|

|

17 |

Dallas |

Texas |

|

|

18 |

Atlanta |

Georgia |

|

|

19 |

Washington |

DC |

|

|

20 |

Las Vegas |

Nevada |

9 |

Different things will be important to companies when looking at business locations. Access to resources like talent and investment can be a critical reason for choosing a particular location. For other businesses, costs such as office space, labour and cost of living are going to be more important. Table 2 sets out the best large cities for access to financial and talent resources and for business costs. On this analysis there is no overlap between the two groups of cities, although the state of North Carolina appears in both.

Table 2a. Cities that rank highly on access to resources including financing, venture investment and human capital

|

City |

State |

|

Irvine |

California |

|

Raleigh |

North Carolina |

|

Austin |

Texas |

|

Lubbock |

Texas |

|

Oakland |

California |

|

Durham |

North Carolina |

|

Laredo |

Texas |

|

San Diego |

California |

|

New Orleans |

Louisiana |

|

Denver |

Colorado |

Table 2b. Cities that rank highly on business costs such as office space affordability, labour costs, corporate taxes and cost of living

|

City |

State |

|

Winston-Salem |

North Carolina |

|

St Louis |

Missouri |

|

Tulsa |

Oklahoma |

|

Jacksonville |

Florida |

|

Oklahoma City |

Oklahoma |

|

St Petersburg |

Florida |

|

Kansas City |

Missouri |

|

Hialeah |

Florida |

|

Tampa |

Florida |

|

Orlando |

Florida |

While an external perspective on the United States often focuses on California, New York and Washington, DC, opportunity for business is spread much more widely. Looking across a variety of business drivers, Table 3 sets out the top 20 American states for business. The more detailed analysis indicates which states are particularly strong in the ten factors important for business, indicating whether the state ranks in the top five, top ten and top fifteen for those factors.

Table 3. Top 20 US states for business

|

Rank |

State |

Workforce |

Economy |

Infrastructure |

Cost of doing business |

Quality of life |

Education |

Technology and innovation |

Business friendliness |

Access to capital |

Cost of living |

|

1 |

Virginia |

Top 5 |

|

Top 15 |

|

|

Top 5 |

|

Top 5 |

Top 15 |

|

|

2 |

Texas |

Top 5 |

Top 5 |

Top 10 |

|

|

|

Top 10 |

|

Top 5 |

Top 15 |

|

3 |

North Carolina |

Top 10 |

Top 5 |

|

|

|

|

Top 10 |

|

Top 10 |

|

|

4 |

Utah |

|

Top 5 |

|

|

Top 10 |

|

|

Top 15 |

|

|

|

5 |

Washington |

Top 5 |

Top 5 |

|

|

Top 5 |

Top 15 |

Top 5 |

|

Top 10 |

|

|

6 |

Georgia |

Top 15 |

Top 15 |

Top 5 |

|

|

|

|

|

Top 10 |

Top 15 |

|

7 |

Minnesota |

Top 15 |

|

Top 10 |

|

Top 5 |

Top 5 |

Top 10 |

|

|

|

|

8 |

Nebraska |

|

Top 10 |

|

Top 5 |

Top 15 |

Top 10 |

|

Top 10 |

|

|

|

9 |

Colorado |

Top 10 |

|

|

|

Top 10 |

|

Top 10 |

Top 15 |

Top 15 |

|

|

10 |

Ohio |

|

|

Top 5 |

Top 10 |

|

Top 15 |

Top 15 |

|

Top 15 |

Top 15 |

|

11 |

Indiana |

|

|

Top 5 |

Top 5 |

|

|

|

Top 5 |

|

Top 10 |

|

12 |

Florida |

Top 15 |

Top 10 |

Top 15 |

|

|

|

|

Top 15 |

Top 5 |

|

|

13 |

Tennessee |

|

Top 5 |

Top 5 |

|

|

|

|

Top 10 |

|

Top 10 |

|

14 |

Massachusetts |

Top 5 |

|

|

|

Top 15 |

Top 5 |

Top 5 |

Top 15 |

Top 10 |

|

|

15 |

Wisconsin |

|

|

|

|

|

Top 5 |

|

|

|

|

|

16 |

Iowa |

|

Top 15 |

|

Top 10 |

Top 15 |

|

|

|

|

Top 15 |

|

17 |

North Dakota |

|

|

|

|

Top 5 |

Top 10 |

|

Top 5 |

|

|

|

18 |

Idaho |

|

Top 5 |

|

Top 15 |

|

|

|

Top 10 |

|

|

|

19 |

Kansas |

|

|

Top 5 |

|

|

|

|

Top 10 |

|

Top 10 |

|

20 |

Arizona |

Top 5 |

Top 15 |

Top 15 |

|

|

|

|

Top 10 |

|

|

Entrepreneurial activity and attitudes in Australia and the United States

Despite almost 98 per cent of Australian businesses being small or medium-sized with fewer than 20 employees,11 the proportion of Australians owning or managing an established business of more than 3.5 years old is only around two-thirds of the rate at which Americans are doing so.12 When it comes to those at the earliest entrepreneurial stage, before anyone has been paid any salaries, Australians are about half as likely as Americans to be in the process of starting a business (5.8 per cent compared to 11.8 per cent).13

It is often said that small businesses are the engine of Australia’s economy. However, the majority of businesses in Australia do not have any employees, around 62 per cent are sole traders.14 They are also not large contributors to wealth, with almost one-quarter of Australian businesses having an annual turnover of less than A$50,000 and more than half having a turnover of less than A$200,000. While some of Australia’s small business activity is due to entrepreneurs starting and running a business, some of it is also due to investment structures, including self-managed super funds (SMSFs), which require the establishment of a trust and an Australian Business Number. There are more than 500,000 SMSFs in Australia.15 The micro businesses (those with zero to four employees) are also the least innovative of Australian businesses. Less than a third reported any innovative activity in 2016.16

Not only are Australians less likely to see business opportunities when a profitable opportunity is spotted, Australians are less likely to act on it than Americans.

Small business activity in and of itself is not a good indicator of entrepreneurism. The comparison data of the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor provides a different lens to look at not only the entrepreneurial activity, but also the attitudes towards entrepreneurship across Australia and the United States.

The importance of role models in entrepreneurship is well established.17 People are likely to follow the steps taken by others, whether that be in a family context or a business context. Knowing someone who has started a business in the past two years is a measure of how visible entrepreneurs are. Australians are less likely to know someone who has started a business in the past two years compared with Americans.18

Perhaps surprising, given the small business data for Australia — not only are Australians less likely to see business opportunities — when a profitable opportunity is spotted, Australians are less likely to act on it than Americans.19 This is despite a larger proportion of Australians agreeing they have the required knowledge, skills and experience to start a business when compared with Americans20 (see Table 4). This may prove problematic as the Australian economy weathers COVID-19.

Table 4. Attitudes and perceptions of Australian and American entrepreneurs

|

|

Australia |

United States |

|

Knowing a start-up entrepreneur: |

55.9 |

60.9 |

|

Perceived opportunities: |

45.7 |

67.2 |

|

Proactivity: |

63.7 |

54.1 |

|

Perceived capabilities: |

70.0 |

65.5 |

Fear of failure is a characteristic of Australian entrepreneurs. The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor data shows almost half of Australian entrepreneurs agree they see good opportunities but would not start a business for fear it might fail, compared with just over a third of Americans.21 Previous USSC research into what causes anxiety in Australians compared with Americans found Australians are more anxious than Americans about a) losing their job or business, b) failure at work and c) losing everything and having to start from scratch.22 Unlike Americans, where high family income results in significantly lower levels of anxiety across these risks, there is very little difference between high and middle-income Australians. One-quarter of both high and middle-income Australians feel anxious about failure at work — this is below 20 per cent of middle-income Americans, dropping to almost ten per cent of high-income earners.

There are several well-told stories of Australian companies pitching for funding to US venture capitalists and being criticised for over-ambitious hockey stick graphs only to be told they are actual sales figures, not projections.

There are two schools of thought on the attitude towards fear of failure amongst entrepreneurs. One is that fear of failure drives success. There are several well-told stories of Australian companies pitching for funding to US venture capitalists and being criticised for over-ambitious hockey stick graphs only to be told they are actual sales figures, not projections. The other is that fear of failure has a chilling effect on taking the risk to start a new business. Given the lower level of entrepreneurship in Australia, this is an issue that warrants further investigation. In the coming months as Australia emerges from COVID-19 lockdown, entrepreneurship will be critical to restarting parts of the economy.

The motivating, knowledge-sharing dynamic of a network of like-minded people is a key concept measured in the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. Beyond this, the importance of a network of interconnected people and ideas as both an enabler of innovation and as an integral part of entrepreneurial ecosystems has recently been examined in the context of founders and funders within the nascent AgTech sub industry. Important for funding, talent and collaboration, a social network analysis has found Australia’s AgTech network is smaller and less dense than the US comparison. Australia also compares poorly to New Zealand on this social network measure. New Zealand with a smaller domestic market appears to have a more global perspective.23

This lack of global perspective is evident in the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor where Australia not only has a lower national scope for its customers and new products or processes than the United States, but only has half the global scope of the United States.

One instantly recognisable aspect of the COVID-19 era is the extent to which it is bringing start-up ecosystem founders and funders together. Facebook groups, Slack channels, webinars are springing up everywhere as entrepreneurs try to make sense of what is happening around them and sharing knowledge about how they are managing the impact on their business. Ironically, the need for social distancing may lead to stronger networks.

Ease of starting a business

Australia is a generally considered an easy place to start a business, however this isn’t reflected in the attitudes of entrepreneurs. Despite the World Bank rating Australia as a very easy place to start a business — one of the top ten countries globally — only around two-thirds of Australians think this is the case. The relatively more challenging American business start conditions are not perceived that way with more than 70 per cent indicating it is easy to start a business24 (see Table 5).

Table 5. Entrepreneurs and the World Bank have different views of how easy it is to start a business

|

|

Australia (%) |

Australia (Rank) |

United States (%) |

United States (Rank) |

|

Ease of starting a business: |

66.8 |

10/50 |

71.2 |

8/50 |

|

World Bank ‘Starting a Business’ rating (2019) |

96.6 |

7/190 |

91.6 |

55/190 |

Entrepreneurship in a COVID-19 era

While the impact of COVID-19 is a day-by-day moving target, lessons from previous downturns indicate how entrepreneurs generally fare. It is partly a positive story, with rates of entrepreneurship increasing as unemployment rises. It is also partly a dire story featuring a significant failure rate.

The US recession following the global financial crisis saw an increase in business bankruptcy filings and closures, and the US economy lost more than 8 million jobs seeing the national unemployment rate double to more than ten per cent. However higher local unemployment rates were found to increase the probability that individuals start businesses.25

Often this takes the form of necessity entrepreneurship, where people start businesses because they need some kind of income. Sometimes this leads to highly-successful businesses able to disrupt a market or create value where none existed previously. Airbnb, Uber and Dropbox all emerged after the GFC. More than 70 US software companies that have raised more than US$100 million in funding were founded between 2008 and 2009.26 In Australia, only one company, Deputy, is in the same category.27 However other Australian software powerhouses Canva, Culture Amp and Brighte were all founded in the years after the GFC and have raised more than US$100 million.28 The case study companies found elsewhere in this report were all founded from 2008 onwards.

While these are the well-known success stories, new ventures typically have a high failure rate. Most fail within the first two years. Analysis of new ventures formed around the DotCom crash found a higher rate of failure within the first two years of operation for those established in 2000-2001 (53 per cent) compared with those established in 1998-1999 (41 per cent).29

One reason is that venture capital funding is likely to become more difficult to obtain. Following the DotCom crash it took a few quarters for venture capital to dry up and once it bottomed out it took three quarters before it started to rise again. A similar trend followed the GFC, but it started to rise again after two quarters.30 However, even at the lowest point post-DotCom crash (Q3 2002), 319 venture capital investments totalling US$3.1 billion were made. Following the GFC’s lowest point (Q1 2009), 594 venture capital deals totalling US$4.7 billion were made.31 This indicates investors are still open to good opportunities.

There are certain characteristics that correlate with success. Analysis of new US ventures32 launched during the period of economic expansion and downturn around the DotCom crash finds a high correlation between the success of the first product and the success of the venture overall. More than three-quarters of new ventures with a successful33 first product survived while just over one in ten that had an unsuccessful first product survived. Products based on radical innovation, serving emerging market needs and using established technology standards were all more successful. Both technology development and an analysis of customer needs were indicators of successful first products.34

In this COVID-19 era, just like prior downturns, there will be big winners as well as big losers. A focus on radical innovation, a strong product-market-fit, technology development and customer needs are the guides to success coming from previous downturns.

Entrepreneurship Framework Conditions for Australia and the United States

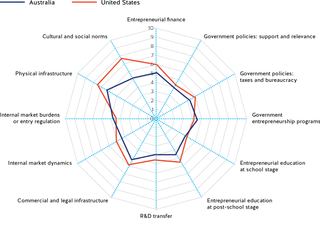

Australia and the United States are both high-income, developed economies. Comparing an assessment of the conditions for entrepreneurship from the perspective of national experts in entrepreneurship35 within Australia and the United States highlights where there are key differences.

While these perspectives about Australia and the United States are effectively self-assessments within each economy and so care must be taken in comparing them, what is clear is that there is a significant difference between the perception of the culture and social norms around entrepreneurship in Australia compared with the United States. The question asked of national experts in relation to this is: Does national culture stifle or encourage and celebrate entrepreneurship, including through the provision of role models and mentors, as well as social support for risk-taking? And experts are asked to rate this statement on a scale from zero (completely false) to ten (completely true).36

Figure 1. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor expert ratings of the entrepreneurial framework conditions in Australia and the United States

Case studies of Australian ventures entering the US market

The following eight case studies of diverse, young Australian ventures37 showcase examples of successful entrepreneurship, outlining how these businesses entered the US market and gained customers.

The founders of these ventures were interviewed in person or by telephone. The interviews sought to understand:

- What relationships the founders had with the United States prior to their current venture.

- What role intermediaries played in advising and assisting market entry.

- The reasons for engaging with the United States.

- Any obstacles that had to be addressed.

- The outcomes of their market entry efforts.

Table 6. Case studies of Australian ventures entering the United States market

|

Venture |

Products |

Sector |

Founded |

|

awe |

Software — SAAS |

Virtual and augmented reality tools |

2016 |

|

Biteable |

Software — platform |

Online tools and content for video production |

2014 |

|

Blisspot |

Digital content subscription |

Platform for wellness advice |

2016 |

|

enigmaFIT |

Digital content subscription |

Consulting in leadership development to major corporates |

2015 |

|

Liquid Instruments |

Software enabled hardware |

Test and measurement equipment using signal processing |

2014 |

|

QuintessenceLabs |

Software and hardware |

Cybersecurity |

2008 |

|

Rosterfy |

Software — marketplace |

Software for event workforce recruitment and coordinatione |

2011 |

|

Snappr |

Software — marketplace |

On-demand professional photography booking service |

2016 |

Case study: awe

Awe provides virtual and augmented reality (VR and AR, together often referred to as mixed reality) tools through a user’s web browser. It is the first commercial, completely web-based platform that supports the creation and consumption of mixed reality experiences across many devices (smartphones, tablets and mobile, desktop and standalone AR and VR goggles).

Although awe was founded in 2016 by Alexandra Young and Rob Manson, its first manifestation, buildar.com, was founded in 2009. awe remains a private company with 12 employees, across Sydney and Europe — where the first customers were. Despite time zone challenges, awe places a high priority on supporting users to make effective use of the tools, and they don’t outsource any of their operations.

The founders of awe considered Australia would not be a lead adopter, building links with the global Augmented Reality community was an objective from the start.

The mixed reality market has been slow to develop but is now beginning to take off, with education and corporate training being the major markets — segments that the founders had not expected to be so strong. Branding and marketing agencies have more recently been a growing segment, with agencies often seeking a form of partnership with awe, in delivery services to the agencies’ customers. The cultural organisation market (galleries and museums) is also growing.

Young and Manson recognised from the outset that the web would be the key platform for augmented and virtual reality and so began with a global mindset. As the founders considered Australia would not be a lead adopter, building links with the global AR community was an objective from the start.

Until recently Young and Manson have focused on building the business and have not invested their time into seeking venture capital. However, as investment could accelerate growth, over the past 12 months they have explored the interest of potential venture capital investors in Australia, Europe and the United States. The growth of the market is beginning to attract larger and better-resourced competitors.

Developing engagement with the United States

awe had contact with the United States from the early years of the business. Young had also lived in the United States for three years. The founders regularly attended the annual Augmented World Expo in the United States and travel to the United States a few times each year to attend conferences for tool developers and increasingly those for AR users. Direct user links and marketing via ‘word of mouth’ has been more significant for market growth than other forms of marketing.

Before founding awe, Young and Manson participated in several pitch events in the United States and met many US venture capital investors. The AR sector as a whole, and web-based AR tools, in particular, were in the early phase of evolution. The investors they met were interested to explore the potential but none were prepared to invest. Those that did show some interest would only consider investing if the company relocated to the United States, something the founders decided against.

While awe had not actively marketed to the education market in the United States, an increasing number of customers from that sector had begun to use the service. Consequently, the founders have had to develop a good understanding of the US education market. In some cases, individual schools use AR for their projects and make independent procurement decisions, but in other cases, school districts or consortia of schools or districts facilitate selection and procurement.

awe is in the process of recruiting US-based staff for the first time, particularly for the education, brand management and advertising market. A US legal firm is being used to advise on the legal and regulatory aspects of employing US staff.

Key insights

- Having a global mindset at the outset is particularly important for emerging technologies where the market is small and evolving in unexpected ways.

- US investors may only be interested in companies that want to relocate to the United States, however, US customers won’t necessarily care where a service is located if it provides the product, service and support customers need.

Case study: Biteable

Biteable provides an online library of animations, video footage and tools to enable users to make their own high-end, studio-quality videos. The platform offers a ‘freemium’ model or a subscription option of US$99 per year.

Biteable was formed in Hobart in 2014 by James MacGregor, Tommy Fotak and Simon Westlake, all of whom had substantial prior experience working together, and founding and running start-ups. While making videos for start-ups, they saw there was growing demand but the time and expense of making an animated video from scratch was a barrier.

The three founders brought together their complementary skills and experience, covering the key dimensions of Biteable’s technology, product development, and marketing and established the company as an online platform with a global perspective from the outset. In 2015, when the venture had attracted 10,000 users, the founders began fundraising. They raised A$1.1 million seed funding with 13 investors, including Sydney venture capitalists Tankstream and BridgeLane Capital and a number of angels. This capital was used to hire engineers and animators to complete further product development, including software and content. They found that Hobart has a strong community of software developers, is a significantly lower-cost location, and experiences much lower levels of staff turnover.

Strong growth continued and by 2018 Biteable had over three million users and raised Series A funding of A$2.8 million from a new Australian venture capital investor, Equity Venture Partners, and further support by Tankstream. These funds were focused on building the marketing and customer service team in addition to continued product development. Biteable now has more than 30 employees. In addition to Hobart, it has opened an office in Melbourne and has begun to recruit staff in the United States and Canada. The focus is further product development and ensuring that all production, administrative, marketing and customer support systems are scalable.

Developing engagement with the United States

By early 2015, with the number of users growing rapidly, only four per cent of those users were based in Australia with the rest across the globe. The United States was Biteable’s largest market from the early days, accounting for about 30 per cent of users. In 2016, Biteable was accepted into Austrade’s San Francisco Landing Pad program and MacGregor moved his family to San Francisco for several months while he worked in the Landing Pad office, drawing on their US market expertise and contacts.

The United States was Biteable’s largest market from the early days, accounting for about 30 per cent of users.

Once there, MacGregor focused on developing partnerships with companies such as Adobe and Shutterstock, better understanding the US market, talking with Australian founders who have raised funds in the United States, talking with relevant US venture capitalists and hiring staff. Biteable is now proceeding to also establish a US entity and continue hiring staff. MacGregor considers it is easier to find people in the United States with strong skill sets in product management and product design. He says “as there are few platforms in Australia that have scaled up to manage a very large number of users, these skill sets are generally less developed in Australia.”

Raising capital for the growth phase is the next major challenge for Biteable. They expect that to be a future focus and involve US venture capitalists. “It is possible to raise Series A in Australia but after that it is difficult — there are few venture capital funds in Australia with the appetite for the level of growth funding we would require,” MacGregor says.

Key insights

- Due to the longer history of digital businesses in the United States, there is a larger pool of experienced talent in many fields.

- Biteable found that there are few venture capital funds in Australia with the appetite for growth funding beyond Series A levels.

- Australian engineering salaries are lower than in Silicon Valley.

Case study: Blisspot

Blisspot was founded by its CEO and serial entrepreneur Deborah Fairfull in late 2016 as an online personal development community. Building on Fairfull’s expertise in counselling, psychology and kinesiology, the platform features articles by experts in the fields of emotional wellness, nutrition, wellness, family and relationships as well as access to a growing online community, expert insight and online courses.

As a web-based venture, Blisspot was global from its founding with a range of personal development content largely coming from a diverse range of third parties. The revenue model is currently based on eCourses — structured guides for personal development intended to be used as self-managed courses — though it is expanding into gamification, events, mobile learning, and wearable technology. In the future, online coaching options may be added on a fee-for-service basis. The market in Australia is now growing strongly.

Fairfull found that the New York immersion program enabled her to develop a larger vision for the venture and the confidence to grow toward that.

Blisspot has developed to this point based on self-funding. However, Fairfull has recently begun efforts to raise capital. While US angels and venture capitalists were considered, the current focus is on raising investment from Australian venture capitalists and particularly, according to Fairfull: “from smart money investors who have a passion for the wellbeing space and can bring useful contacts”. Fairfull considers that an Australian investor which matched that profile would be preferable because of the scope for regular interaction. Blisspot is now located at Fishburners at the Startup Hub in York St, Sydney.

Developing engagement with the United States

The launch of the Springboard Program,38 a personal and professional development program for women, brought Fairfull into contact with the New York immersion program of FD Global Connections at a time where more than 70 per cent of Blisspot’s users were in the United States. The customer base had grown through passive marketing — customers found Blisspot through web searches — and active marketing, using Facebook ads.

The program in New York involved extensive briefings on all aspects of doing business in the United States and introductions to senior advisors and potential partners. Fairfull found the program valuable: “it was fantastic, it opened many doors and changed me as a businessperson — it opened my horizons”. The experience led Fairfull to consider corporate clients in addition to direct interaction with customers.

The FD Global Connections program also provided introductions to some US venture capitalists, which Fairfull approached as an opportunity to build relationships for possible future investment. She keeps in touch with these venture capitalists and updates them on Blisspot’s progress. The potential US investors provided validation for the business concept and stressed the importance of ensuring that all aspects of the business model were scalable.

Fairfull found that the New York immersion program enabled her to develop a larger vision for the venture and the confidence to grow toward that. She did not find major differences between the business cultures of New York and Australia.

Key insights

- Web interest from US customers may indicate a sweet spot for market entry.

- Organisations such as Austrade, Springboard and FD Global Connections can assist start-up founders in assessing the opportunities and refining the products and services offered, the business model or the vision for the company.

Case study: enigmaFIT

Phillip Campbell founded his third company, enigmaFIT, in 2015 after more than 25 years working in the field of cognitive science; and extensive involvement with leadership development in multinational companies across diverse industries. enigmaFIT focuses on assessment and development of senior executive capabilities, particularly ‘agility and adaptive expertise’ for managing change in complex and ambiguous contexts.

enigmaFIT grew strongly in Australia prior to adopting a focus on the US market in 2017. Having staff in Australia to support ongoing client relationships and development enabled Campbell to focus on other markets. enigmaFIT had not raised capital at this stage as the development of capabilities, services and client numbers enabled steady growth in staff and revenue in Australia.

Developing engagement with the United States

Campbell is an American Chamber of Commerce (AmCham) governor and visited the United States for marketing his business. He had also participated in an AmCham innovation-focused mission and stayed a few weeks after the mission to continue market research.

Campbell found that specialist professional advice was essential — the regulatory requirements in the United States, at the Federal, State and city level, can be complex.

While enigmaFIT had some major customers in the United States, the objective in engaging further was scaling-up their presence, with a focus on major corporates in New York.

After positive feedback from initial introductions, and deciding to launch in New York, Campbell needed advice on the complex US federal and local regulatory requirements. His AmCham links also helped with establishing further links in New York, including with Austrade, Australia’s New York Consul General and with the American Australian Association in New York.

He knew that developing a network in the target market was vital, and having decided to focus on the New York market, Campbell engaged FD Global Connections, a consultancy specialising in assisting Australian firms to expand their business in the United States, to assist with introductions to potential clients and advisors. The enigmaFIT launch event in New York, organised by FD Global Connections, was attended by over 20 senior executives from major global companies — three of which became enigmaFIT clients within three months of the launch. enigmaFIT’s clients in the United States now include Boston Consulting Group, Loews Corporation, Novartis, a leading global fashion company and a global coffee company. The company now has an office in New York.

Campbell considers that enigmaFIT has benefited greatly from the professional support provided by Austrade, the American Australian Association and the detailed guidance and targeted introductions in New York by FD Global Connections. Campbell found that specialist professional advice was essential — the regulatory requirements in the United States, at the federal, state and city level, can be complex. Withholding tax needs to be addressed and visas for staff can be particularly difficult. Establishing relationships with local service providers, including for financial services, is vital for effective business operations. The ability to do business in the United States could be delayed by six to 12 months if these business establishment issues are not sorted out, Campbell says.

Campbell’s experience shows the importance of being clear on the target market and identifying the appropriate people, and their roles, in the target organisations. As recommendations are vital for a new entrant, having clients prepared to provide case studies in networking and marketing events is valuable. This, and other evidence of the value of the service for clients, helps to ‘de-risk’ for buyers.

Campbell found the United States to be more open to networking; good relationships with one contact often led to introductions to their contacts. He found the Australian business culture to be more reserved in comparison.

Key insights

- Understanding the US federal and local regulatory requirements for establishing a business in the United States is critical. Not getting this right can significantly delay the ability to do business.

- Having existing customers prepared to provide case studies at networking or marketing events is valuable.

- US connections are more open to networking, and more prepared to share relevant contacts.

Case study: Liquid Instruments

Liquid Instruments was founded in 2014 by a team of twelve researchers from the School of Physics at the Australian National University (ANU). The team’s leader and the CEO of the firm, Daniel Shaddock, is currently a Professor in Physics at ANU. Shaddock got his PhD at ANU but spent five years in the United States at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory as a postdoctoral researcher. He returned to Australia but continued working for NASA for several years, travelling often back to the United States and building up a strong team of postdoctoral fellows and students at ANU.

When the major project with NASA was coming to an end, Shaddock looked for a way to keep the research team going and formed Liquid Instruments.

The foundation of Liquid Instrument’s core technology was developed as tools for fundamental research — specifically as instruments to detect gravitational waves. The main product is a device (Moku:Lab) that can be programmed to function in a range of analysis applications based on signal processing, (that is software-enabled hardware). At this stage, the device can be used for at least 12 specific applications. Liquid Instruments currently provides free software upgrades — which can substantially increase the utility of the device platform — to all customers.

At founding, an initial investment of A$1.3 million came from two local venture capital sources: ANU Connect Ventures (with funds from the Motor Traders Association of Australia (MTAA)); and Australian Capital Ventures Limited (ACVL), an early-stage investment fund formed by the Hindmarsh construction and property development company. Seed stage funding from the United States was deemed an unlikely prospect, even though the amount of investment from US seed investors would likely be higher and the share of equity they would require likely to be lower than comparable Australian seed investors. While the entrepreneurial ecosystems in Australia are strengthening, Shaddock found few advisors and mentors in Australia had deep experience of scaling a new venture in this technology space.

ANU was flexible in supporting the formation of the company. Liquid Instruments negotiated a research contract with the ANU through which all staff formally remained as employees of the university, reducing their career risks. In exchange for equity, the ANU assigned to Liquid Instruments the intellectual property developed by the group while employees of the ANU.

Liquid Instruments’ hardware device was initially manufactured at ANU but is now manufactured in Malaysia by a company that has become an investor in the venture.

Developing engagement with the United States

From his prior work at NASA, Shaddock had extensive links in the United States and was always aware the United States would be the venture’s largest potential market. He estimates the United States would account for about 30 per cent of a potential global market of around US$25 billion, while Australia would be about half a per cent.

The venture was commercialising a potentially disruptive technology, that would challenge a range of more specialised instrument manufacturers. But, as it is based on research tools, the underlying technologies were largely in the public domain — although also on tacit knowledge and key skills that were not. The combination of the firm’s unique hardware design, software and chip with encrypted digital signal processing form a strong barrier to entry for potential competitors. The team decided upon a key strategy of early-market entry and rapid scaling — this would lower unit costs and enable continuous upgrading to maintain technology leadership. Hence, in approaching the United States, the initial priority was marketing.

Shaddock estimates the United States would account for about 30 per cent of a potential global market of around US$25 billion, while Australia would be around half a per cent.

It was considered essential to form a US entity as the limited reputation of Australian companies in the development of high-tech devices was expected to be a potential barrier to adoption. Sales to US customers — largely universities, research organisations and increasingly corporates — would be assisted by the perception that Liquid Instruments was a US firm. The initial market has been largely research organisations, particularly in fields familiar to the founders of Liquid Instruments. However, due to the increasing capability of the venture to widen the range of applications of the instrument the hitherto unfamiliar, but the larger, industrial testing market was also attractive.

With the formation of Liquid Instruments in the United States, the Australian entity became a subsidiary. Nevertheless, the 15-strong engineering team remains in Australia. Liquid Instruments has found that the technical talent they need is available in Australia at a lower cost than in Silicon Valley.

One of the co-founders at ANU, US citizen Danielle Wuchenich, returned to the United States but later worked on business development — marketing and building a global distributor network – for the venture. As the Chief Strategy Officer, Wuchenich now has executive responsibilities in management and marketing and is the venture’s US representative. The venture now has 17 distributors around the world, operating in 30 countries.

Second stage engagement

After entry and rapid growth in the US market, Shaddock sought additional capital for expansion. Although the venture has benefited from two ‘Accelerating Commercialisation’ grants from the Australian government, it was difficult to raise venture capital in Australia. Capital raising for hardware ventures is often more challenging than for a software venture as the time scales are often longer, the challenges of production greater and the costs and risks higher. However, as Liquid Instruments already had an established production relationship and growing sales, the business model was established.

It was also difficult to develop links to US venture capitalists while based in Australia, as the Australian networks did not generate any ‘serious introductions’ to US venture capitalists. Therefore, as part of a strategy to raise capital in the United States, Liquid Instruments decided to work with Austrade’s San Francisco Landing Pad and make its co-working space the office for Wuchenich. A US angel investor who Shaddock had met in Australia became a key link into US venture capital firms. He also invested in the venture. The search for investors led to raising US$8.16 million in Series A capital from investors that included a US venture capital firm, Anzu Partners, the Malaysian manufacturing partner and ANU Connect Ventures.

Having a longstanding member of the team who is a US citizen with strong links in the United States has been a valuable cultural bridge. Shaddock has found that while the culture in California is not too different from Australia, this is less the case in other parts of the United States. This bridge is likely to also be important as the venture grows, recruits staff in the United States and integrates them into the overall team. Good links with the United States have helped Liquid Instruments get into the networks. Being well received by some in those networks, their referrals can be a great help to extend credibility, as the investors tend to be quite collaborative.

Key insights

- A strong network can provide an ideal initial customer base.

- For some products and services, creating the perception of being an American company can assist the sales and marketing approach.

Austrade

The Australian Government’s Trade and Investment Commission (Austrade) assists Australian businesses to succeed in trade and investment with expertise in connecting Australian businesses to the world and the world to Australian businesses. In the United States, Austrade has offices in Chicago, Houston, New York, San Francisco and Washington DC.39

Austrade’s San Francisco Landing Pad

Austrade’s San Francisco Landing Pad40 provides market-ready start-ups and scale-ups with potential for rapid growth a cost-effective option to land and expand into the United States. It provides a three-month residency program for Australian ventures through which participants benefit from advice and a program of workshops covering topics from legal and accounting essentials to marketing and pitching in the United States. The San Francisco Landing Pad also facilitates introductions to mentor networks and strategic partnerships designed to drive growth. The Landing Pad has relationships with accelerators, universities, government entities, corporate innovation offices and investors. It also has close links with the Aussie Founders Network, a member-driven community of Australian founders, investors and industry advisors in the Bay Area. Participants also benefit from post-residency business advice to help them continue to grow their business.

The Landing Pad’s Australian entrepreneur’s guide to the San Francisco Bay Area includes details on preparing for a US expansion, the nuts and bolts of establishing and growing a company in the United States, and an overview of the diverse resources available to Australian entrepreneurs during the journey. Austrade’s resources for entrepreneurs include guides to doing business in a range of US cities, reports on six sector-specific US clusters, and guides on specific aspects of US regulations.

FD Global Connections

Sydney-based FD Global Connections41 helps scale-ups, small business and mid-sized companies prepare to launch into the US market. It provides a range of support services including:

- Assessing a firm’s international readiness;

- Developing a “Go-To-Market” strategy which involves researching locations, competitors and local messaging for the target market and distribution strategies;

- A New York City Immersion Program which facilitates entry to the New York City target market by connecting Australian companies with FD Global Connections’ deep US networks, including local business partners who can assist with key market-entry roles such as sales, business development, and technical and account managers. Other US and international target markets are also served by FD Global Connections.

Trena Blair, the Founder and CEO of FD Global Connections, lived and worked in New York and has a particular passion and track record for preparing and successfully launching Australian companies in New York.

Aussie Founders Network

The Aussie Founders Network (AFN)42 is a member-driven community of Australian founders, investors and industry advisors. Its ambitious mission is to support, build and elevate the role and impact of the Aussie tech community, globally. AFN grew out of informal networking among Australian founders in Silicon Valley but was formally launched in 2016. A New York chapter was launched in May 2019.

AFN has produced two resources that are invaluable for start-ups looking at growing business in the United States:

- Aussie Startup Advice: USA, a nine-episode podcast that AFN co-produced with Austrade (http://www.aussiefounders.org/podcast)

- Rockstar Aussie Founders Living in the USA, a publication AFN co-produced with the Australian Computer Society (http://www.aussiefounders.org/publication).

Case study: QuintessenceLabs

QuintessenceLabs (QLabs) is a cybersecurity company with a portfolio of products that enable the protection of data by combining advanced data protection capabilities with quantum technology.

Vikram Sharma founded QLabs in Canberra in 2008 and remains its CEO. Its technology was based on research on quantum technology conducted at Australian National University (ANU) by Sharma and others. Growing concern about cybersecurity coupled with a large public sector market, including several security agencies, made Canberra (where QLabs is headquartered) a strong foundation market for QLabs.

QLabs has a team of 50, including 30 engineers, with offices in Canberra, Brisbane and San Jose, California. QLabs also has a sales and support presence in the United Kingdom and business representation in Washington DC. Asia is an expected growth market over the coming couple of years.

Participation in relevant trade shows and taking up opportunities for speaking at US conferences also contributed to the development of a network in the United States.

It took six years and substantial support from investors for QLabs to develop its first product. Its investors are predominantly Australian with the addition of one major European investor. Westpac has been both a major customer and a major investor through two rounds of funding in 2015 and 2017. QLabs also received an A$3.26 million grant from the Australian Department of Defence’s Innovation Hub in 2017 and has benefited from the government’s R&D Tax Credit program. QLabs remains a private company and collaborates with researchers at several Australian universities.

QLabs’s strategy is for steady rather than rapid growth, responding to a changing and growing market. The current focus is on major vertical markets (government, finance, defence and cloud), particularly in the United States. While the Australian market remains important for QLabs, growth into the large global security markets in North America and the European Union — where new regulations such as General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) have strengthened the demand for cybersecurity solutions — is also an opportunity.

In February 2020, QuintessenceLabs, announced that it secured an investment from In-Q-Tel, Inc. the non-profit strategic investor that accelerates the development and delivery of cutting-edge technologies to the national security communities of the United States and its allies.

Developing engagement with the United States

As the largest IT security market in the world, there is a strong incentive for QLabs to establish itself in the United States. A US office was opened in 2014 and by late 2018 had seven staff recruited from the United States, most in business development with one in a technology support role. QLabs manufacture their equipment in Silicon Valley through a contract manufacturer having found suppliers prepared to manufacture small volumes at competitive quality and price.

To support marketing, QLabs developed a partnership with a Washington DC-based strategic consulting and engineering firm established and managed by a team of former senior technology executives from the US intelligence community. QLabs’s partner had strong links into the US market, particularly government. Establishing links with US consultants and partners was challenging and QLabs has relied on the advice of their network in forming links and assessing potential partners. QLabs also found Austrade advice and support helpful.

In 2017 QLabs formed partnerships with two US companies who incorporated technology into their products and services, PKWARE (an enterprise software company), and VMware (a subsidiary of Dell Technologies that provides cloud computing and other services). More of these alliances are likely to develop through a Technology Alliance Partnership program that QLabs has developed.

QuintessenceLabs has now built a foundation for continued growth in the United States with strong manufacturing capabilities, a support team, and global business development, as well as strategic technology partnerships with US companies.

Sharma’s prior involvement in US organisations assisted in developing networks and gaining entry to the US market, in particular his links with NASA (QLabs’s first US office was at a NASA facility). Participating in US trade shows and speaking at conferences also contributed to the development of a network. QLabs was recognised in the 2015 SINET (Security Innovation Network) awards, backed by the US Department of Homeland Security Science and Technology Directorate, and was named a Technology Pioneer in 2018 by the World Economic Forum, both of which raised its profile in the United States and beyond.

Market development in the United States requires substantial investment to learn about the market and to develop relationships, which was possible due to QLabs’s strong financial position, resulting from investor support. QLabs had its first significant sale within six months of entering the US market.

QuintessenceLabs has now built a foundation for continued growth in the United States with strong manufacturing capabilities, a support team, and global business development, as well as strategic technology partnerships with US companies such as VMware, PKWARE, NetDocuments, and a number of channel partners.

Key insights

- Development of leading-edge technology requires patient investment.

- Strong networks and partnerships in the target market can assist with both growth and assessing opportunities.

- US conferences and trade shows are a good way of reaching the right target market and building a US network.

Case study: Rosterfy

Bennet Merriman and Shannon Gove co-founded Rosterfy — initially called Event Workforce Group — in 2011. The two were students of sports management and commerce at Deakin University and the work experience requirement of the course presented their business problem — organising work experience is a discovery and coordination challenge for both the students and the workplaces. Facilitating work experience placements was the initial focus of Rosterfy.

By 2012, they had expanded interstate, hired their first employee and brought in a third co-founder, Chris Grant, a friend and software developer. A more sophisticated product was launched in 2013 and Rosterfy grew rapidly and extended to workforce recruitment and coordination for events of all sorts — more than 1,000 per annum by late 2014. At this stage, they also began licencing their event workforce software and providing client support to event owners who could then organise their own workforce. In addition to supporting recruitment for events, Rosterfy began working with tertiary institutions to provide casual work opportunities, event industry training and certificates.

Rosterfy now has clients in 11 countries, which has raised the necessity to develop multilingual capacity.

Developing engagement with the United States

The organisers of one of the major Australian endurance events, Tough Mudder, recommended Rosterfy to the organisers of the US Super Bowl. This led to the ventures’ first client in the United States and exposure to the US market. Rosterfy has now supported four Super Bowls. In 2017, it used its workforce management technology to help mobilise 30,000 volunteers at the Super Bowl, the largest volunteer workforce in the event’s 50-year history.

Merriman and Gove followed up by attending US industry conferences and assessing US market opportunities. They also joined the San Francisco Landing Pad’s first cohort in 2016. Landing Pad participants are given an operational base for up to 90 days — in Rosterfy’s case, this was in RocketSpace, a start-up accelerator hub whose alumni include Spotify and Uber. The Austrade Landing Pad also provided tailored business development assistance.

Merriman found that interacting with the other ventures in the Landing Pad and with the Aussie Founders Network in San Francisco were great sources of information and support. These links led to relationships with an accountant and an insurance broker — both Australian-owned — in the United States. The Landing Pad base also led to a partnership with Verified Volunteers, which facilitates background checks on volunteers.

Merriman found that interacting with the other ventures in the Landing Pad and with the Aussie Founders Network in San Francisco were great sources of information and support.

Rosterfy has found participating in industry conferences to be particularly useful for marketing and lead generation. In particular, industry conferences highlighted the key role state and city-level sports commissions play in coordinating sporting events in their area.

Their experience in the Landing Pad opened a wide range of links and of opportunities to explore, but it became very clear that these would become overwhelming without a clear idea of objectives and strategies — even if these changed over time. As opening the market in the United States became a focus, it was also essential that the Australian business was ‘on an even keel.’

Rosterfy has now established a US company with one of its co-founders and two employees while the team in Australia has grown to four. The business in the United States is growing steadily and major new clients include the Aspen Ski World Cup. Although the sales process in the United States is similar to that in Australia, Merriman found that the US market is very competitive, with lower margins. Rosterfy has found that the good reputation of Australians in the United States for hard work and trustworthiness has helped to open doors. However, they have found that employment regulation in the United States is more flexible than in Australia and this aspect of recruitment and management for events is less challenging.

The venture may seek venture capital in the future, but if it does so, the founders intend to first look locally in Australia for investors. They would also consider raising capital in the United States if the investors could also assist Rosterfy’s growth in the US market.

Key insights

- A recommendation from an existing customer can provide valuable information on how to explore opportunities in new markets.

- Australians have a reputation in the United States for hard work and trustworthiness which can open doors.

- US conferences and trade shows are a good way of reaching the right target market, building a US network and developing market intelligence.

Case study: Snappr

Snapper was co-founded in 2016 by Ed Kearney and Matt Schiller who had experience with another venture, Gown Town, which they founded in 2012 to sell graduation gowns to university students. Gown Town had been quite successful, and the two founders planned to expand throughout Australia and then to the United Kingdom and the United States. Thinking about how to broaden their business’s offerings and counteract intermittent market demand, they explored the scope for adding photography services. A pilot program offering photography services indicated strong demand, an opportunity for attractive margins and scope for a more scalable business than graduation gowns. This ultimately led to a decision to focus on the photography services market through a two-sided market, linking a diverse range of customers with photographers who are validated through interviews and a review of their portfolio.

Planning entry to the United States

Kearney and Schiller realised the best way to deal with potential competitors replicating their business model was to build market share and reputation as quickly as possible in the largest market. They formed Snappr, raised some funding from Australian angel investors and initially focussed on growing the business in the Australian market while assessing how to launch and raise funds in the United States. Snappr grew rapidly in Australia, enabling the partners to develop processes for recruiting and assessing photographers and validating the business model. Product focus was on removing the ‘pain points’ for the customer: how much will this cost; will the photographer I approach be available; and how quickly can I finalise an arrangement?

Interacting with a range of other start-ups and advisors helped Snappr to strengthen the business model and develop a much clearer strategy for implementing the business and managing growth in the United States.

Pursuing their strategy to enter the US market, Snappr applied to join Y Combinator, a world-renowned Silicon Valley-based seed funder and start-up incubator. Based on the success of its business model in Australia, it was accepted and a team of six from Snappr were based in the United States at Y Combinator for three months in 2017. A Snappr employee also worked in the San Francisco Landing Pad.

After pitching at the Y Combinator’s well-known ‘Demo Day’, Snappr raised US$2 million from a range of investors, including US angels, a small US venture capital fund and the Australian venture capital fund, AirTree.

Interacting with a range of other start-ups and advisors at Y Combinator helped Snappr to strengthen the business model and develop a much clearer strategy for implementing the business and managing growth in the United States. The key learnings were to focus on ‘getting the product-market fit right’.

Developing engagement with the United States

San Francisco proved to be a very expensive location — the costs of establishing the head office there was financed by the capital raised in Australia and the seed funds from Y Combinator. However, Snappr has now launched in a succession of US cities. First up and down the west coast and then in the ‘NFL cities’ — those large enough to have a national football league team. Preparing to launch in each city involved developing the supply side, by recruiting photographers, and marketing through digital channels, including paid channels. The market that has developed is roughly evenly spread across the business sector and families. Since launching in the United States, growth has been strong and sustained.

Snappr has used US legal firms to convert the firm into a US corporation and to advise on the legal aspects of the relationship with the photographers they use. Y Combinator also assisted with managing US legal and regulatory issues.

Key insights

- San Francisco is an expensive location to establish an American head office.

- Well-respected incubators can assist with getting the ‘product-market fit’ right, setting start-ups up for strong and sustained growth.

Engaging with customers in the United States: Insights from the case studies

Each of these start-ups founders was asked to reflect on their experience of growing their business in the United States. Although the start-ups have different histories and are in different industries, the lessons they drew from their experience share several themes:

Preparation and planning

Be prepared — the pace of change can be fast, there may be setbacks, finding a strong product-market fit may take iterations. Having a strong drive, tenacity, clear long-term goals and a focus on the customer problem and on your key growth challenges will help keep on track.

US markets are larger, generally more competitive and have lower margins than Australia, despite being fragmented across states. Preparation prior to marketing or capital raising in the United States pays dividends. This means gaining an understanding of the industry and regulatory context; understanding US legal, taxation, and general IP frameworks; developing clarity and focus around objectives; ensuring that all aspects of the business model are scalable; and assess the costs of doing business, including flights, housing and insurance.43

Building networks

While the business relationships are strongly transactional and a very upbeat presentation of the business case is essential, most people in US businesses are inclined to be helpful and to respond positively to ambition and talent.

Networks can provide a ‘springboard to the market’, through referrals and leads, and provide insights into the target markets.

Build networks and be proactive in creating opportunities to be an insider in an industry and ecosystem. The best way into the market — industry conferences, key initial clients and recommendations, web-marketing — will depend on the industry. However, experience shows that in the United States, developing a network in the target market is vitally important. Networks can provide a ‘springboard to the market’ through referrals and leads, and provide insights into the target markets. These networks can also help with recruitment in the United States and with capital raising. However, funding the travel and networking over the time needed to build a profile in the United States may require substantial resources.

Developing support networks among advisors, mentors, other founders and investors is also likely to be essential.

Consider an incubator or accelerator

A number of the ventures had benefited from a short period in an appropriate and — often specialised — incubator. The Australian ventures that did participate in US incubators benefited from the advice on their business model and marketing strategy and on managing growth in the United States. Interaction with other founders in the incubator also provided information and support that the founders considered valuable. Nevertheless, founders should vet incubator and accelerator programs before applying to enter, taking into account: location, whether the facility has the appropriate industry and mentor networks, and whether the equity terms are reasonable.

The Landing Pad program provides a tailored residency for scaling Australian tech companies. Unlike traditional accelerators that may charge a fee or take equity, the Landing Pad is a taxpayer-funded initiative that provides free, non-diluting services including office space, market-entry round tables and workshops, and bespoke business development assistance to participants. While the US Landing Pad is San Francisco-based, it links ventures with Austrade’s network across the Americas.

Professional advice

Most of the ventures found that specialist professional advice was needed to understand the complex US federal and local regulatory requirements. Relationships with local service providers and often locally recruited staff is essential for effective business operations. Incubators and intermediaries, such as the Landing Pad and FD Global Connections, provide advice on local service providers and can also provide connections to US contacts that participants value highly. Consider locations outside Silicon Valley, which will often be cheaper and more relevant to particular industries.

US subsidiary or headquarters?

Some of the case study ventures found that the reputation of Australians in places such as Silicon Valley meant that the Australian origins and ownership of the venture was not a barrier to market entry. Others, particularly in precision hardware, considered that being seen as a US company would present fewer barriers to customer acceptance. Those ventures that did form a US entity maintained their product development teams in Australia — they had found that the ‘talent’ they needed was in Australia and at a substantially lower cost than in the United States. However, close links with networks in the United States was invaluable for market development. Prior market traction in Australia can help with credibility but having a good US customer base has a greater impact.

The most-relevant entrepreneurial ecosystem

Many entrepreneurial ecosystems and clusters are developing in the United States outside Silicon Valley. These tend to be specialised in specific industries or technologies (for example, San Diego for biotech; Boston for digital health technologies; Seattle for business software; New York for fintech or media).44 For some ventures, one of these locations may offer a more appropriate and lower-cost base than Silicon Valley.45