Executive summary

- China is increasingly assertive in its militarisation of maritime features and use of coercion in the South China Sea. This not only undermines the national interests of Southeast Asian states but also the rules-based maritime order.

- While Australia and the United States already pursue a range of security cooperation activities in Southeast Asia, this report examines how they can work together to strengthen the maritime security resilience of key Southeast Asian partners.

- The report brings together four leading experts from Indonesia, the Philippines, Singapore and Vietnam to explore what role Australia and the United States could play in supporting more robust maritime security capabilities with their countries.

- For Indonesia, Ristian Supriyanto looks at how exercises and patrols; defence capability transfers; industrial and technological collaboration; and education and training can be enhanced, with a focus on trilateral military exercises and coordinated patrols.

- For the Philippines, Renato De Cruz Castro discusses how Manila’s bilateral security relations with each partner have struggled to align trilaterally and why legal frameworks need to be updated to support Manila’s force modernisation efforts.

- For Singapore, Collin Koh examines how the robust access, training and logistics arrangements with both partners can also support more holistic cooperation to build regional security resilience such as infrastructure financing.

- For Vietnam, Lan-Anh Nguyen focuses on how Australia and the United States can play complementary roles in supporting capacity building and maritime domain awareness while also improving multi-domain resilience.

- The report concludes by outlining four possible pathways by which Australia and the United States could support their Southeast Asian partners.

- The first pathway is to accelerate naval and coastal shipbuilding programs. The second is to prioritise lethal high-end munitions and strike capabilities. The third is to expand maritime surveillance data-sharing. The fourth pathway is to increase Australian and US access arrangements and expand presence operations.

- Australia and the United States should consider how to better identify joint lines of effort across these four pathways and the relative trade-offs they involve.

- The report makes an important contribution to policy debates about how Australia, the United States and Southeast Asian partners can work together in the South China Sea in the coming years.

1. The challenge of collective resilience in maritime Southeast Asia

Peter K. Lee, United States Studies Centre

China’s escalating pressure in the South China Sea

Over the past decade, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has steadily gained the “upper hand” in the South China Sea over Southeast Asian states.1 Claiming 80 per cent of these waters and almost all land features under its so-called ‘nine-dash line,’ the PRC has clashed with Southeast Asian claimants, especially in the Spratly Islands. The PRC initially asserted that it was building facilities for scientific research, ecological conservation, and maritime rescue and navigation, but it is now clear that these bases have primarily military functions.2 In practice, the PRC seeks de facto control over disputed features and to be able to dictate the conditions under which other states transit these waters.3

The PRC has become more assertive and sophisticated in its use of maritime “grey zone” activities to coerce and dominate its Southeast Asian neighbours in crises short of armed conflict.4 The People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM), China Coast Guard (CCG), and People’s Liberation Army-Navy (PLAN) vessels have been at the forefront of this campaign.5 The PRC has also engaged in an unprecedented program of dredging and land reclamation. These fortified outposts are the centrepiece of the PRC’s campaign to change the status quo without resorting to the use of military force. In March 2022, US Indo-Pacific commander Admiral John C. Aquilino stated that the PRC had “fully militarised” three of its outposts at Mischief Reef, Subi Reef, and Fiery Cross Reef in the Spratly Islands.6 The PRC now deploys anti-ship and anti-aircraft missile systems, military jamming equipment, anti-submarine warfare aircraft and airborne early warning aircraft to these outposts.7 The strategic value of the outposts in any high-level military contingency remains disputed, but their existence under PRC control adds a new dynamic to military planning for all states.8

Southeast Asian responses to maritime coercion

Southeast Asian states share a desire to prevent the militarisation of the South China Sea and potential conflict in these waterways. But presenting a unified front is complicated by the differing threat perceptions and territorial stakes among Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) member states. ASEAN’s official position emphasises maritime security and safety, mutual trust and confidence, and peace and stability in the South China Sea.9 Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam have competing claims to maritime features. Indonesia disputes the PRC’s nine-dash line infringing on its maritime boundaries. Mainland Southeast Asian states such as Cambodia, Laos and Thailand are not directly implicated in such territorial disputes but have a role to play as ASEAN member states in collective negotiations.

Southeast Asian claimants have tried different methods to respond to PRC maritime coercion, with mixed success. The PRC’s actions undermine the 2002 ASEAN–China Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (DOC). It also hinders efforts to negotiate a Code of Conduct in the South China Sea (COC) that would establish a legal and diplomatic mechanism between ASEAN and the PRC.10 As such, at different points, Southeast Asian claimants have attempted quiet diplomacy, high-level talks, public condemnation, collective negotiations via ASEAN, and appeals to international arbitration. The most notable example of the latter is the Philippines’ successful 2016 Permanent Court of Arbitration ruling against the PRC’s nine-dash line claim.11 Claimants and non-claimants alike have also increased funding for force modernisation and maritime capacity, expanded their coast guards, and conducted naval exercises with each other and extra-regional partners.12 But the reality is that Southeast Asian states, individually and collectively, have struggled to deter the PRC’s maritime coercion.13

Australian and US interests in the South China Sea

In May 2022 a People’s Liberation Army Air Force’s (PLAAF) Shenyang J-16 fourth-generation fighter jet conducted a dangerous intercept of a Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) P-8A Poseidon maritime patrol aircraft on a routine surveillance mission in the South China Sea. The PLAAF J-16 flew only metres in front of the P-8A, firing flares and releasing aluminium chaff into its engines.14 As highlighted by US Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Mark Milley, the incident was merely the latest in a series of PRC actions to deny aircraft and vessels access to the airspace and waters around its disputed maritime claims.15 Such incidents threaten escalation into a major crisis.

Extra-regional partners such as Australia and the United States clearly have strategic interests in the South China Sea.

Extra-regional partners such as Australia and the United States clearly have strategic interests in the South China Sea. Though they take no position on disputes over ownership of contested features, both countries reject the PRC’s maritime claims. They assert that states should peacefully resolve their differences in accordance with international law and norms.16 Extra-regional partners have little direct territorial interest in undersea oil and gas extraction or fisheries but a long-standing interest in ensuring freedom of transit and navigation.

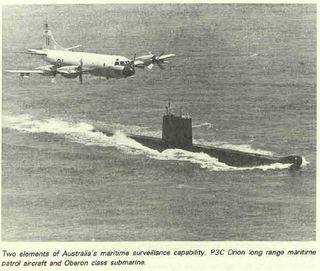

The South China Sea was first mentioned in the 2011 Australia-United States Ministerial Consultations (AUSMIN) Joint Communiqué and is an area for alliance cooperation.17 Australia and the United States nonetheless view the South China Sea in distinct ways. The 2020 Australian Defence Strategic Update defined the South China Sea as part of Australia’s “immediate region” within which it “must be capable of building and exercising influence in support of shared regional security interests.”18 But the South China Sea has been a priority theatre for defending Australia’s national interests for more than a century due to geographic proximity and dependence on maritime trade.19 Australia’s presence in these waters long predates the PRC’s recent interventions, with maritime surveillance patrols having previously focused on the Soviet naval presence at Cam Ranh Bay in Vietnam during the Cold War.20 Australia today has vital economic interests at stake, with nearly two-thirds of its exports flowing through these waters to Northeast Asia.21 Successive Australian governments have thus viewed the increasingly contested South China Sea environment as a long-term task in which shaping the norms of behaviour is just as important as high-end warfighting.22

For the United States, the shifting balance of power in the South China Sea presents emerging risks for how it is able to project power and defend its allies and partners in the Western Pacific.23 The South China Sea is only one of several flashpoints in dealing with the PRC’s growing power which also includes the Korean Peninsula, the East China Sea, and the Taiwan Strait.24 This leads to some differences between the two allies, such as US freedom of navigation operations which Australia has traditionally been more cautious about.25

Aligning Australian, US and Southeast Asian responses

Attempts by Australia and the United States to support Southeast Asian states in maritime crises have produced mixed reactions. A decade ago, a more cautious US approach to supporting Southeast Asian partners was often criticised, such as the US response to the 2012 Scarborough Shoal standoff between the Philippines and the PRC.26 In that instance, the Philippines sought clarity that its Mutual Defense Treaty with the United States would apply in the case of a Chinese attack inside the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone (EEZ). It did not receive such reassurance from the Obama administration, which instead offered the Philippines increased intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) support, US$30 million in military financing, coast guard cutters, and increased bilateral military exercises.27 These contributions did not ultimately prevent the PRC’s de facto control of Scarborough Shoal. Subsequently, the Philippines’ presidential office declined US support in later instances, including the 2021 Whitsun Reef standoff.28

Extra-regional partners like Australia and the United States, but also Canada, Japan and European countries have tried to be more responsive and forceful in responding to PRC coercive provocations in recent years. This includes diplomatic criticism, increased aerial surveillance flights, freedom of navigation operations, and transits and forward deployment by European vessels.29 However, these actions have often appeared to go beyond what Southeast Asian states themselves are prepared to do. For example, the 2020 West Capella incident was sparked when the PRC intervened against Malaysia’s West Capella drillship operating in the South China Sea.30 The United States initiated a major military presence operation of aircraft, bombers, submarines and warships to closely monitor Chinese activities.31 While some experts hailed the response as a “model for naval statecraft,”32 Malaysia criticised the actions as insufficiently consultative.33 As the above two examples suggest, there remains a gap in how to respond to PRC coercion between some Southeast Asian states and their extra-regional partners.

Australia and the United States currently pursue multiple streams of maritime security cooperation with Southeast Asian partners. For decades, Australia’s Defence Cooperation Program (DCP) has funded training, exchanges and exercises, as well as conducted surveillance missions. The United States has long-standing maritime cooperation activities with its treaty allies the Philippines and Thailand, and the US Indo-Pacific Maritime Security Initiative (MSI) funds capacity-building and maritime domain awareness programs.34 Australia and the United States also work multilaterally with other extra-regional partners to provide diplomatic, capacity, and operational support to Southeast Asia. Australia is updating partnerships like the Five Power Defence Arrangements (FPDA) and, together with the United States, is strengthening the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue to respond to China’s challenge to the regional maritime order.

Between these two streams of effort — bilateral and multilateral — there exists a third option: Australia-US alliance cooperation with key partners.

Between these two streams of effort with Southeast Asia — bilateral and multilateral — there exists a third option that has received increasing interest in Canberra and Washington: Australia-US alliance cooperation with key partners.35 As John Bradford, senior fellow in the Maritime Security Programme at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore, has recently argued in the case of US-Japan alliance cooperation with maritime Southeast Asia, “the modernised Alliance operational structure serves as a force multiplier which is increasingly magnifying the capabilities and effectiveness of the two allies’ maritime initiatives in Southeast Asia.”36 Bradford notes five areas where an alliance can be a ‘force multiplier’ beyond separate efforts, including leveraging allied bases adjacent to the South China Sea, combined operations such as for humanitarian assistance, partnerships that play to each ally’s strengths, extra-regional coordination, and cooperative capacity-building such as integrating US electronic sensors on Japanese-gifted TC-90 aircraft for maritime patrols. The same logic and aspirations apply in the Australia-US alliance.

Many hands make light(er) work

This report argues that supporting key Southeast Asian partners’ resilience in the maritime security domain serves their national interests as well as Australian and US objectives. A focus on ‘resilience’ also complements ASEAN’s “2018 Vision for a Resilient and Innovative ASEAN,” which emphasises the need to address maritime challenges in a “coordinated, integrated and effective manner.”37 Resilient partners may or may not respond more assertively to PRC coercion, but weak partners do not have that choice. As one recent report by prominent Southeast Asian scholars concluded: “The greatest value of external players lies in helping empower the strategic, economic, and even social capacity of regional states to determine their own policy choices.”38 The fact is that these states will continue to assess and respond to PRC activities in the South China Sea in accordance with their national interests, just as Australia and the United States do. Empowering key strategic partners to be more self-reliant for their own maritime security is vital to upholding a rules-based order in the South China Sea.

The report primarily focuses on ‘maritime security cooperation’ as it relates to inter-state challenges to sovereignty at sea. Each author draws on the national contexts of how ‘maritime security cooperation’ is understood in their specific countries. Nonetheless, this broadly corresponds to the ‘regional security’ and ‘anti-crime’ categories of maritime security cooperation as outlined by ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) working groups.39 These issues include the militarisation of disputed features, use of maritime militias, freedom of navigation and overflight, maritime sovereignty, use of coast guards, maritime law enforcement, and patrol and resupply interference. Some of the following chapters also address aspects of ‘maritime safety’ such as search and rescue and environmental protection insofar as they relate to national resilience against coercion rather than general erosion of security.40

The report looks at the specific cases of Indonesia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Vietnam. Australian and US policymakers regularly identify these four countries as critical to any successful Southeast Asia security strategy in documents such as the 2016 Australian Defence White Paper and the 2022 US Indo-Pacific Strategy.41 These countries also represent a diverse cross-section of the region’s political diversity, national power, population size, geography, and maritime security capacity.42 While the Philippines and Vietnam are claimants in the South China Sea, Indonesia’s disputes primarily focus on the PRC’s expansive nine-dash line claims and Singapore has no direct disputes with the PRC. The opportunities for what Australia and the United States can jointly do with each state therefore varies, but by focusing on four countries that both see as priorities, the report can better compare the triangular dynamics of alliance cooperation.

There are other states that could have been included, such as Malaysia, Thailand, or Brunei. Malaysia in particular is an important partner for Australia and the United States, and it has experienced PRC maritime coercion as mentioned above in the case of the West Capella incident.43 Australia maintains deep defence relations with Malaysia as part of the FPDA, its 2021 Comprehensive Strategic Partnership, and a military presence at Royal Malaysian Air Force Base Butterworth in Malaysia. Nonetheless, Singapore was chosen for examination rather than Malaysia based on the strong momentum of its recent security cooperation with Australia and the United States and greater scope for expansion relative to Malaysia.44 Many of the recommendations proposed in this report nonetheless will be applicable to Malaysia, Brunei, and even Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia to an extent.

There is a growing constituency throughout Southeast Asia who recognise that existing responses have been insufficient and that new strategies are needed.

This report goes beyond official Southeast Asian government positions in exploring opportunities for more robust cooperation with Australia and the United States. There is a growing constituency throughout Southeast Asia who recognise that existing responses have been insufficient and that new strategies are needed.45 These include voices at the highest levels in these countries, including the former Philippine Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana’s pointed criticism of PRC fishing fleets, Indonesian Defence Minister Prabowo Subianto’s ambitious defence procurement agenda and calls by experts for Vietnam to take the PRC to arbitration.46

The Southeast Asian contributors to this report offer diverse perspectives on the role that Australia and the United States can and should be playing in the region. This is a reminder that there are many different voices within Southeast Asia than those usually heard outside the region. This report hopes to generate more vigorous discussion than either official talking points or not-for-attribution commentary have offered to date. The contributors offer insight into important debates unfolding throughout Southeast Asia about how to best respond to the PRC’s maritime coercion and what role Australia and the United States should be playing. Perhaps most valuably, their judgements may portend nascent changes in Southeast Asian strategic outlooks, especially in the contested times ahead.

2. Indonesia and China’s maritime encroachment: Opportunities for Australia and the United States

Ristian Atriandi Supriyanto, Universitas Indonesia and S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies

Introduction

The second half of 2021 witnessed Indonesia facing one of its toughest maritime security challenges to date. For months, Indonesian and PRC naval and law enforcement vessels were embroiled in a protracted standoff near the Natuna Islands. Though bilateral maritime incidents had previously occurred, the 2021 standoff was the first of its kind. Past bilateral maritime incidents merely concerned Indonesia’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ) over fishery rights, but, between July and December, the PRC challenged Indonesia’s oil drilling inside the Continental Shelf.47 In response, Indonesia deployed naval and law enforcement vessels to counter the PRC’s so-called ‘grey zone tactics.’ Driving these tactics is Beijing’s skewed ‘historical’ interpretation of international law, particularly the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), to fit its ‘nine-dash-line’ (9DL) claim.48 Indonesia and the PRC may continue their ‘waltz-like’ standoff in the South China Sea, resulting in occasional bilateral tensions.49

The integrity of Indonesia’s maritime borders are thus in the interest of Australia and the United States.

Time, however, is not on Jakarta’s side. Maritime incidents between the PRC and Indonesia have increased and will only grow in both frequency and intensity. Jakarta has little capacity to counter, much less deter, such tactics.50 While Indonesia’s main maritime security challenge remains poaching, marine resource disputes between Indonesia and the PRC are less commercial than geopolitical in essence.51 The South China Sea is a contested geopolitical theatre between China, on the one hand, and the United States and its allies, especially Australia, on the other. Any military conflict between them is unlikely to spare Indonesian waters and airspace due to geographical imperatives. US and Australian military manoeuvres between the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea must transit through the Indonesian archipelago. This could invite PRC encroachment during a military conflict for sabotage or attack in order to defend its control over the 9DL.52 The integrity of Indonesia’s maritime borders — which challenges the PRC’s 9DL — is thus in the interest of Australia and the United States. Canberra and Washington could help Indonesia in this regard through critical initiatives in four areas: exercises and patrols, capability transfer, industrial and technological collaboration, and education and training. These four areas are interrelated and overlap, but scrutinising each area can reveal current gaps for new initiatives.

Exercises and patrols

Exercises and patrols are an area where outcomes can be achieved more rapidly with Indonesia, even if only in terms of publicity. While Australia and the United States are Indonesia’s most frequent partner countries in combined military exercises, their interactions assume both bilateral and multilateral formats. Bilateral exercises can be tailored to specific requirements, but ‘multiple bilaterals’ may exhibit little compatibilities, create duplications, and overstretch limited national resources. Multilateral exercises, on the other hand, promote a diversity of activities but can become all-too-inclusive and subject all participants to the lowest common denominator. Instead, the ‘sweet spot’ may reside in trilateral or ‘minilateral’ cooperation that caters to a specific scope of interests, activities, or regions. Examples of such minilateral exercises include coordinated patrols in the Malacca Straits and Sulawesi (Celebes) Sea that involve Indonesia and up to three other littoral states.

Recently, joint and combined multinational military exercises have pursued a trilateral or minilateral format. Exercises Super Garuda Shield and Crocodile Response 2022 can set the standards for future trilateral and minilateral cooperation. Super Garuda Shield originally started as a confidence-building exercise between the Indonesian and US armies, but it expanded in 2022 to include army contingents from Australia, Japan, and Singapore, as well as select involvement of multinational naval and air force units.53 The expansion owed largely to the initiative of Indonesia’s commander-in-chief’s rapport with his US military counterparts, as well as Indonesia’s less-publicised concerns over the PRC’s maritime encroachment.54 Meanwhile, Crocodile Response signified the inaugural trilateral exercise between the Australian, US and Indonesian civilian and military agencies on humanitarian response.55

The two exercises above may provide cues for future trilateral and minilateral collaboration involving Australia, Indonesia, and the United States. For instance, the US-Indonesia CARAT and Australia-Indonesia New Horizon naval combat exercises could proceed under one series, with the participation of air force maritime surveillance units. If naval combat exercises may seem too ambitious, maritime law enforcement or ‘white-hull’ agencies provide an alternative. With the Australia-Indonesia coast guard-fishery Gannet patrols as an example, Indonesia can invite the US Coast Guard and Australian Border Force for a trilateral exercise near the Natuna Islands.56 Another potential can grow out of the Indonesia-Singapore Defence Cooperation Agreement, which welcomes third countries in bilateral exercises.57 Since Australia and the United States are already the top military exercise partners of both Indonesia and Singapore, the upgrade to a minilateral format among them seems natural.58

Strategic wargaming exercises, such as on Taiwan or South China Sea military conflict scenarios, could serve as additional US and Australian initiatives to improve collaboration among Indonesian civil-military agencies, especially between diplomats and military officers. Academic institutions or think tanks are suitable partners in these exercises, which could also invite other Southeast Asian participants and instructors to ‘regionalise’ the scope of interactions in these scenarios. A regional approach is warranted as, given the scale and impact of these scenarios, they are likely to implicate not just Indonesia, but also all of Southeast Asia.

Capability transfer

Capability transfer is another area where trilateral and minilateral collaboration can take shape. To date, the transfer of arms and equipment proceeds in a rather fragmentary and disparate fashion due to ‘siloed bilateralism’: the capabilities from one donor country may not be compatible with those from the other partners. Perhaps a defence or military model of the World Bank’s erstwhile ‘Consultative Group on Indonesia’ (CGI) is relevant for US and Australian consideration.59 A coordinated, if not collaborative, Australia-US approach to building Indonesia’s defence — especially maritime — capabilities could ensure their long-term operational sustainability, as opposed to mere institutional-bureaucratic accomplishments for the donor nations.

A coordinated, if not collaborative, Australia-US approach to building Indonesia’s defence — especially maritime — capabilities could ensure their long-term operational sustainability.

Capabilities to improve Indonesia’s maritime domain awareness (MDA) are already a top US priority, such as the US-funded Integrated Maritime Surveillance System (IMSS) in 2008 and eight ScanEagle maritime surveillance drones operated by the Indonesian Navy’s newly formed Squadron 700 in Juanda, Surabaya.60 However, the IMSS requires Indonesia’s dependence on US proprietors for maintenance and repair, which the former resented given its insistence on self-reliance.61 But it does not have to be. When transferring capabilities to Indonesia, the US and Australia should empower Indonesia’s self-reliance, if not self-sufficiency, which is partly the objective of industrial and technological collaboration covered in the next section below.

In capability transfer also lies the promise of the Quadrilateral Security Partnership or the ‘Quad’. In addition to the Indo-Pacific Partnership for Maritime Domain Awareness (IPMDA),62 the Quad could assist with the construction and operation of offshore patrol vessels (OPVs) with custom designs for Indonesia’s white-hull agencies such as the coast guard-equivalent, Indonesian Maritime Security Agency (Badan Keamanan Laut, Bakamla), and fishery surveillance unit of the Ministry of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries (Kementerian Kelautan dan Perikanan, KKP).63 More and bigger white hull vessels could enable Indonesia to counter PRC grey zone activities near the Natuna Islands, but fuel shortages often hamstring their operations. By partly offsetting white-hull operational costs, the Quad could stiffen Indonesia’s resistance to the PRC’s maritime encroachments rather than just enabling these agencies to observe such activities at a distance. Empowering Indonesia’s white-hull agencies to operate at sea may reassure Jakarta of the sincerity of the Quad powers to defend Indonesia’s maritime rights and interests.

Industrial and technological collaboration

Capability transfer to Indonesia should not just be about furnishing Indonesia with more arms and equipment. More importantly, such transfer should take into account Indonesia’s domestic industrial capacity to sustain the lifecycles of these capabilities. Though Indonesia’s defence industrial capacity is limited by research funding and development expertise, it nonetheless has shown some nascent growth in platform manufacture and assembly lines. The United States and Australia could sustain this growth by channelling resources, financial or otherwise, into Indonesia’s defence industry to produce and/or assemble units. Copyright terms and conditions and classification protocols may become potential issues, but they are not insurmountable in the case of basic platform designs and assembly. Australia and Indonesia, for instance, have started collaborating to assemble Bushmaster armoured personnel carriers at Indonesian plants.64 Following the Bushmaster example, the United States and/or Australia could bid for the 33-tonne stealth ‘fast missile boat’, which the Indonesian Navy plans to acquire up to 120 units.65

Barring this, the United States and Australia could offer Indonesia a proprietary role in the manufacturing of arms components or sub-components. In addition to platforms, Indonesia’s reliance on US arms exports lies in the area of munitions, especially torpedoes (such as Mk 46 and now-obsolete Mk 44), guided bombs, and missiles. With Australian support, the United States could allow Indonesia some legal and technical leeway to assemble, if not manufacture, the export version of these munitions. Though catered mainly to Indonesia’s own requirements, the assembly line should be available for export to third countries with US and/or Australian clearance and licenses.

Education and training

Ultimately, the implementation of all of the above initiatives depends upon the decisionmakers and operators in the field. Their understanding of the initiatives should not just be practical and technical, but also strategic. Education and training must nurture cadres of the future to build compatible ‘mindsets’ not just during joint exercises and patrols. Building Indonesia’s interoperability with the United States and Australia starts from the brain. Absent compatible mindsets, miscommunication and misunderstanding can quickly emerge and sow Indonesian doubts about Washington-Canberra sincerity behind these initiatives. For instance, in 2021 the Indonesian Defence Ministry agreed to send Indonesian officer cadets to study at Australian “defence educational facilities.”66 These cadets could establish long-standing personal rapport and networks with Australian (and US) officials, which would be critical during the implementation of joint initiatives.

More US and Australian collaboration in scenario or threat-specific initiatives could elevate Indonesian operational standards.

Education and training, however, should go beyond mere exchanges of military staff and students. More US and Australian collaboration in scenario or threat-specific initiatives could elevate Indonesian operational standards, such as in cyber and electronic warfare where experience counts much more than education and training. Learning from experienced instructors or facilitators then becomes a vital part of education and training. With US support, Australia and Indonesia established the Jakarta Centre for Law Enforcement Cooperation (JCLEC) whose activities include scenario-based maritime security table-top exercises, which the US-funded Bakamla Maritime Training Centre (BTC), once built, will follow suit.67 These exercises incorporate real-life contingencies with which Indonesian officials may only have little experience, if at all. Cyber and electronic warfare should thus be a focus in future multinational exercises that JCLEC and BTC organise.

Next steps

In the short to medium term, or between five to 15 years, exercises and patrols as well as capability transfer seem to be the most likely initiatives to take hold. Among all the initiatives, exercises and patrols are relatively the quickest to plan and yield outcomes, which, unfortunately, tend to be measured merely in the extent of their publicity and press coverage. Capability transfer is a much longer process, usually a decade or more, from the statement of intent for capability acquisitions to obtaining political approvals from the donor country. Equally important, the transfer should be concomitant with building Indonesia’s capacity to operate and service these capabilities more or less independently of their donors.

Meanwhile, industrial collaboration as well as education and training require a period of more than 15 years, which befit long-term planning. Industrial collaboration requires significant investments not only in money, but also in both time and personnel to adequately prepare for transfer in technology, skills, and experience. Industrial collaboration is thus contingent upon the education and training of the relevant workforce. While the immediate objective of education and training is to develop personal networks among officials, its ultimate aim should be cultivating interdependent partnerships where trilateral and minilateral collaboration exists across all domains in the other initiatives. After all, the sustainability of these initiatives depends on the decisionmakers and operators in the field who should see the value of collaboration not just in their practical and technical matter, but importantly, in the wider strategic picture: the inescapability of the Indonesian archipelago in US-China competition over maritime access and control in the South China Sea.

3. Philippine-Australia-US security cooperation for maritime security

Renato Cruz De Castro, De La Salle University

Introduction

A little-known fact in the latest 26 May P-8 Incident between Australia and the PRC in the South China Sea is that the Australian P-8 maritime surveillance aircraft had been flying out of Clark Air Base in the Philippines.68 The incident revealed that Australia and the Philippines share a mutual interest in continued regional security and stability in the face of the looming PRC challenge in the South China Sea. It also showed that both sides had shared real-world military operations, most recently during the 2017 Siege of Marawi City when the RAAF deployed two AP-3C Orion aircraft that provided surveillance and reconnaissance support to the Philippine military’s combat operations against the Muslim militants.69

Prior to 2016, it has been argued that security ties between Manila and Canberra have evolved slowly.70 However, under the Duterte administration, the Philippines became more strategically important and relevant to Australia.71 This led to opportunities for heightened security cooperation on training, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR), and capacity-building support.72 This chapter addresses how Australia and the United States can better support the Philippines in defending its maritime security interests. Specifically, it explores how the United States and Australia can assist the Philippines in modernising its navy and coast guard, and in developing its capabilities to address the PRC’s grey zone operations in the South China Sea.

China’s grey zone operations and the Duterte administration

Despite the Philippines’ rapprochement with China under the Duterte administration, PRC grey zone operations in the South China Sea remain unabated. On 20 March 2021, then-Department of National Defence (DND) Secretary Delfin Lorenzana officially informed the Philippines about the presence of around 220 blue-hulled PRC fishing vessels moored in line formation at Julian Felipe Reef (internationally known as Whitsun Reef).73 According to him, the Philippine Coast Guard (PCG) sighted 220 Chinese fishing vessels, allegedly manned by the PRC maritime militia, as early as 7 March 2022. Filipino military officers and diplomats interpreted the gathering of PRC fishing vessels in Whitsun Reef as a prelude to a grey zone operation similar to what happened in Mischief Reef in 1995 and again in Scarborough Shoal in 2012.74

The then-Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) Chief Lieutenant General Cirilito Sobejana directed the Philippine Navy (PN) to immediately deploy additional naval vessels to reinforce the country’s “maritime sovereignty patrols” in the disputed waters. Former Secretary Lorenzana ordered the PCG and Philippine Navy to increase their sovereignty patrols near Whitsun Reef. The Philippine Air Force’s (PAF’s) reconnaissance planes conducted several aerial reconnaissance flights near PRC-controlled land features despite being challenged by the People’s Liberation Army Navy’s (PLAN) forces. The PCG activated its “Task Force Pagsasanay (Training)” to intensify the capacity building of its personnel and assets to protect the Philippines’ EEZ amid the tense and critical stand-off. This incident revealed that, whether a littoral Southeast Asian country is appeasing or challenging the PRC, Beijing’s grey zone operation will remain business as usual.

The revitalisation of Philippine-Australian security relations

Under the Duterte administration, the Philippines tried to move away from its traditional and formal security ties with the United States towards closer economic and political alignment with the PRC. Early on, President Duterte was predisposed to downgrade relations with the United States and engage in more multi-faceted interactions with Russia and the PRC. On 12 September 2016, President Duterte declared that the contingent of US Special Forces operating in Mindanao must leave the country, arguing that there could be no peace in this southern Philippine island as long as US troops were operating there.75 The following day, he declared that the Philippine Navy would stop joint patrols with the US Navy in the Philippines’ EEZ to avoid upsetting the PRC.76 During his two-day official visit to Vietnam in late September 2017, he promised that the Philippine-US Amphibious Landing Exercise (PHILBEX) 2016, which took place from 4-12 October 2016, would be the last military exercise between the two allies during his six-year term.77 President Duterte explained that, while he pledged to honour the long-standing defence treaty with the United States, the PRC opposed joint military drills in the Philippines. This left him no choice but to serve notice to the United States that this would be the last joint military exercise between the two allies.78

In late September 2017, President Duterte announced that he would forge “new alliances” with the PRC and Russia to cushion the fallout from the possible withdrawal of the United States from the Philippines.79 President Duterte also announced that he was inclined to review the 2016 Enhanced Defence Cooperation Agreement (EDCA) although the Philippine Supreme Court had declared in finality that it was a constitutional agreement. President Duterte’s threat to distance the Philippines from its formal treaty ally and to unilaterally abrogate the EDCA was his reaction to Washington’s growing criticism of alleged human rights violations resulting from his anti-narcotics/anti-criminal campaign in the Philippines.80

These developments led, however, to a dramatic improvement in Philippine-Australian security relations. The Philippines has long-standing defence cooperation with Australia facilitated under a series of bilateral agreements, including the 1995 Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) on Cooperative Defence Activities, and the 2007 Philippine-Australia Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) that offers legal guarantees for Australian forces conducting joint-counter terrorism exercises in the Philippines. It also commits the Australian Defence Force (ADF) to advise the AFP on logistics and its acquisition policy.

President Duterte’s efforts to gravitate closer to Beijing alarmed Canberra, as this would strain Philippine-US relations. However, this allowed Australia to enhance its security ties with the Philippines, given that Washington and Canberra are the only two countries with formalised security arrangements with Manila. Moreover, given that Philippine-Australia security relations partly operate within the context of the US-led hub-and-spokes system of bilateral alliances in Asia, the bilateral relationship between Manila and Canberra was seen as robust enough to stand on its own.81

President Duterte’s efforts to gravitate closer to Beijing alarmed Canberra, as this would strain Philippine-US relations. However, this allowed Australia to enhance its security ties with the Philippines.

The following four bilateral defence arrangements reflect the dramatic improvement in Philippine-Australian Security relations.82 First, there is the Australian Embassy Note 482/17, October 2017. Signed by the Australian Embassy in Manila and by the Department of Foreign Affairs, the Note enumerates several forms of defence cooperation between the AFP and the ADF, such as operational support against organised armed groups in the Philippines, the provision of training and advisory role upon the request of the Philippine Government on enhancing intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance, enhanced maritime security engagements and patrols and the temporary deployment of ADF and civilian personnel in the Philippines. Second, there is Operation Augury—Philippines, 2017, a training program conducted by the ADF to the AFP that was established after the five-month battle for Marawi City. The program has trained more than 10,000 AFP personnel in urban combat and joint operations, air coordination in the urban environment, and maritime security.

Third, there is the September 2018 Terms of Reference (TOR) on Cooperation between the major services of the Philippines and the Australian Armed Forces. This agreement completes the series of armed services’ exchanges by adding the Terms of Reference of the Philippine Army-Australian Army Staff Talks that designated the guidelines and procedures for Army-related activities between the Philippines and Australia. It should be pointed out that PN-RAN Strategy Talks began in December 2015, while the PAF-RAAF Airman-to-Airman Talks commenced in September 2017. Finally, the signing of the 2021 Philippine Australia Mutual Logistic Support Arrangement (MLSA) is the most significant recent security arrangement between the Philippines and Australia which is expected to deepen the two countries’ security partnership. The agreement allows Philippine and Australian naval ships and air force aircraft to refuel and access each other’s military bases.83

The improvement in the Philippine-Australian security partnership coincided with the rapid pace of the AFP modernisation program.

The improvement in the Philippine-Australian security partnership coincided with the rapid pace of the AFP modernisation program. The Philippine Air Forces acquired a squadron of FA-50 lead-in fighter planes and re-established the Philippine Integrated Air Defence System (IADS). The Philippine Navy got its three guided missile frigates from South Korea and eight locally-made fast attack craft. In June 2019, the Duterte administration agreed to bankroll the second phase of the AFP’s 15-year modernisation program. This phase provides big-ticket items that the AFP would acquire, with the bulk of the US$56 billion modernisation fund going to the Philippine Navy and the Philippine Air Force. This development has two implications: 1) the development of the Philippine Navy and Philippine Air Force creates opportunities for joint training exercises between the AFP and the Australian Defence Force (ADF) on territorial defence; and 2) this will strengthen the Philippines’ political will and capabilities to confront PRC grey zone operations in the South China Sea.

The revival of the Philippine-US alliance: Implications for the Philippine-Australia partnership

Following tumultuous negotiations throughout 2021 over terminating and then maintaining the 1999 Visiting Forces Agreement, the Philippines and the United States announced on 16 November 2021 the “Joint Vision for a 21st Century United States-Philippines Partnership” to revive Philippines-US security relations after President Duterte’s efforts to marginalise the alliance as part of his failed efforts to appease the PRC. The document states the two sides’ intention to ensure the Mutual Defense Treaty’s relevance in addressing current and emerging threats. It also mentions their common efforts to support a mutual understanding of the two allies’ roles, missions, and capabilities within the alliance.84 These developments indicate both countries’ consensus on the need to transform the Mutual Defense Treaty from a mere consultative mechanism to an anchor that will provide stability to their alliance as they address common security challenges they will face throughout the 21st century.85

On 29 September 2022, Philippine DND Undersecretary and Officer-in-Charge Jose Faustino and US Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin formally announced their countries’ commitment to the 1951 Philippine-US Mutual Defense Treaty.86 This will be accomplished by enhancing maritime cooperation and improving their respective armed forces’ interoperability and information sharing. Both defence secretaries also acknowledged the necessity of improving and modernising their alliances to help secure the Philippines’ future, address regional security challenges, and promote peace and security in the Indo-Pacific region.87 This goal requires the two allies to accelerate the implementation of the EDCA by concluding infrastructure enhancements and repair projects at existing EDCA-agreed locations inside five Philippine Air Force (PAF) bases all over the country. This will also entail the two allies exploring new locations that will be built to create a credible mutual defence posture. And finally, the two defence secretaries announced the signing of the US-Philippine Maritime Framework that will jump-start the two countries’ maritime cooperative activities in the South China Sea, which might include the resumption of joint naval patrols by the US and Philippine navies.88

These developments have two implications for the Philippine-Australian security partnership. First, they offer Australia the opportunity to assist the United States in tipping the scale as the Philippines adjusts its appeasement policy towards the PRC to one characterised as limited hard balancing as this would encourage Manila to challenge PRC expansion in its maritime domain. Second, they provide the United States and Australia the chance to organise other American treaty allies, Japan and South Korea, who are also the Philippines’ security partners, to coordinate their efforts to help modernise the AFP and strengthen Manila’s will to confront the PRC’s grey zone operations in the South China Sea.

To maintain momentum in the Philippine-Australian security partnership, Canberra should consider the following recommendations.89 First, there should be an enhancement, or at least sustainment, of the quality of activities conducted under the Philippine-Australia defence and security cooperation partnership, ensuring that progress is made in all said activities, especially on joint training and capability building. The Philippines and Australia should maximise the benefits of the 2021 MLSA during their conduct of military exercises and visits by RAN ships and RAAF planes in the Philippines. The Philippines might also consider allowing the temporary deployment of more RAAF reconnaissance planes in PAF bases across the country to enhance the AFP’s maritime domain awareness (MDA) capabilities. Second, a clear, focused, and strategic engagement plan on defence and security engagements with Australia and other partner countries at the defence department level should be formulated; and current country-specific engagement plans at the AFP level should be revised and regularly updated to take into account new developments at the domestic, regional, and global context.

Canberra should also cooperate with Washington, Tokyo, and Seoul in engaging Manila in a vigorous training and education program relative to the Philippine military modernisation.

Third, the institutionalisation of strong and credible planning, monitoring, assessment, and documentation mechanisms and processes with the Joint Defence Cooperation Committee (JDCC) and the Defence Cooperation Working Group (DCWG) with Australia to be able to set the strategic direction of the bilateral defence and security cooperation and more adequately track and chart its progress. Fourth, the creation of a Military Cooperation Working Group (MCWG) between the Philippines and Australia that would address both countries’ issues and concerns on defence and security cooperation at the military level. Fifth, Canberra should inform Manila that it will expand the scope of its security partnership to include PRC grey zone operations in the South China Sea. The two countries’ navies and coast guards should also conduct joint training on countering grey zone operations at sea and increase the number of Philippine-Australian joint naval and air exercises focusing on territorial defence and confronting PRC grey zone operations.

Conclusion

To assist the United States and its other allies in tipping the scale in the Philippines’ shifting policy toward the PRC, Canberra should also cooperate with Washington, Tokyo, and Seoul in engaging Manila in a vigorous training and education program relative to the Philippine military modernisation and holding joint trilateral patrols in the South China Sea. Canberra can also assist Washington in organising other allies in forming a consortium that will program and systematise their military training, assistance and sales to the Philippines and manage the competition among the allied countries’ commercial arms sales to Manila. And, finally, Canberra needs to ponder the prudence of its opportunistic policy of boosting the Philippine-Australian security partnership to the point that it will be robust enough to stand on its own without considering that this partnership exists and operates within the broader context of the US-led hub-and-spokes system in the Indo-Pacific region.90

4. A Singaporean perspective on maritime security cooperation with the Australia-US alliance

Collin Koh, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies

Introduction

How Singapore approaches maritime security cooperation with Australia and the United States logically stems from the island city-state’s high dependence on access to critical sea lines of communications for its national prosperity and survival. It also hinges on the country’s geostrategic position emanating from its lack of strategic depth and being practically “boxed in” by larger neighbours that sit aside those key sea routes. Singapore has not publicly espoused any overt threat to its national maritime interests. Given its paucity of an exclusive economic zone and a distant-water fishing fleet — beyond the post-9/11 emphasis on counter-terrorism and piracy, Singapore naturally faces a holistic spectrum of potential maritime security challenges to seaborne trade and freedom of navigation, generally couched in terms of threats to “good order at sea.”

While Singapore has not traditionally considered the PRC a maritime security threat, in recent years Beijing’s activities have posed two challenges to Singapore’s maritime interests. First, PRC port and infrastructure development in recent decades, which largely reflected the country’s growing economic might and influence, has taken some shine off Singapore’s position as once the top premier seaport. While commercial in nature, this challenge has also started to filter into Singapore’s immediate neighbourhood. For example, Beijing’s investments in Malaysia’s East Coast Rail Link may potentially incentivise shippers to bypass the Straits of Malacca and Singapore (SOMS) and thus result in a loss of business for Singapore.91

The second challenge is how the PRC’s growing military might and assertiveness in regional geopolitical flashpoints could sharpen a sense of strategic uncertainty. In this regard, Beijing’s continued military and coast guard build-up in the proximate South China Sea, continued disregard of the 2016 arbitral award and documented instances of maritime coercion against its Southeast Asian rivals in the disputed areas challenge the rules-based order. As a non-claimant but nonetheless still a keen stakeholder in the South China Sea, Singapore’s pervading interests would be to safeguard freedom of navigation and overflight; ensure the continued viability of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and regional security architecture; as well as to maintain crisis stability despite the ongoing and likely persistent China-US rivalry.92

Singapore’s view of maritime coercion

By “maritime coercion”, one should perhaps look beyond the application of kinetic force. If this broadened definition is adopted, Singapore has been subject to such grey zone instances before. But the country has so far not been subjected to kinetic forms of coercion from China. The closest, most recent example would be Singapore’s maritime standoff with Malaysia off Tuas in late 2018, during which the former pitted its navy and coast guard against the latter’s civilian vessels in what constituted a form of “grey zone” challenge. Beijing’s coercion of Singapore over the South China Sea was indirect, subtle perhaps. Following Singapore’s statement that took note of the 2016 arbitral award on the South China Sea,93 the island was embroiled in an exchange of public barbs with Beijing, and soon after Singapore’s consignment of Terrex fighting vehicles was detained in Hong Kong.94 While there was no clear evidence to show that Beijing was behind the Terrex incident, the timing was too tantalising to be written off as a mere coincidence — not when Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong was also not invited to the Belt and Road Summit in May 2017, despite the country being one of the most supportive of the Belt and Road Initiative in Southeast Asia.95

To deal with maritime coercion, Singapore has relied on indigenous solutions that suit its operational environment. Notably, its navy inaugurated the Maritime Security and Response Flotilla in early 2021 — taking lessons from the 2018 Tuas standoff with Malaysia to create a specialised unit optimised to deal with such grey zone instances.96 Given its capabilities, Singapore could adequately cope with foreign maritime coercion within its territorial sea — chiefly against threats emanating from its immediate neighbourhood. Against other, “indirect” types of grey zone challenges, the island city-state has promulgated relevant, but at the same time, controversial laws, notably the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act of 2019 to deal with disinformation97 and the Foreign Interference (Countermeasures) Act of 2021.98

Extra-regional access and presence

A major facet of Singapore’s approach is to ensure the continued engagement of friendly extra-regional powers to help maintain peace and stability. The provision of access to military facilities, especially the frequent port calls by extra-regional maritime forces such as those of Australia and the United States to Singapore’s Changi Naval Base and Sembawang Wharves, for example, facilitate the logistical sustainment of their regional operations, including in the South China Sea. Australia and the United States are major players with whom Singapore has cultivated tight military interoperability. Australia is a member of the Five Power Defence Arrangements (FPDA), which has served as a useful platform for Singapore and Malaysia to build maritime defence and security capabilities through joint exercises and information exchange. The Singapore Armed Forces (SAF) maintains a large training presence in Australia, such as the Shoalwater Bay Training Area (SWBTA) in Queensland. The SAF conducts Exercise Wallaby, involving all three armed services, in SWBTA. Under this framework, the SAF and the Australian Defence Force also conduct a tri-service exercise codenamed Trident, which involves high-end capabilities and complex manoeuvres such as amphibious landing operations.99

A major facet of Singapore’s approach is to ensure the continued engagement of friendly extra-regional powers to help maintain peace and stability.

Singapore regards the United States as its primary security partner with close defence engagements stretching over decades, buttressed by a series of milestone bilateral documents. Namely, these documents are 1) the 1990 MOU Regarding United States Use of Facilities in Singapore that grants access to SAF facilities such as Changi Naval Base and Paya Lebar Air Base; 2) the 2005 Strategic Framework Agreement that designated Singapore as a Major Security Cooperation Partner; and 3) the 2015 Enhanced Defence Cooperation Agreement (EDCA). The United States is the primary source of state-of-the-art weapon systems for the SAF, especially combat aviation, and a major provider of training ground access. Some of the high-end SAF training exercises, such as Forging Sabre, conducted in the United States were crucial in validating new warfighting concepts.100 Moreover, it must not be overlooked that bilateral training exercises have been deep and extensive in scope.

Both Australia and the United States maintain a military logistics presence in Singapore through their facilities in Sembawang Wharves under the FPDA and the Commander, Logistics Group Western Pacific (COMLOG WESTPAC) arrangements, respectively. For example, the littoral combat ship USS Montgomery, following her arrival in Singapore in July 2019, carried out numerous missions in the South China Sea from Changi Naval Base, including the first freedom of navigation operation off Chinese-occupied features in the contested Spratly Islands in 2020.101 In addition, under the 2015 EDCA, the US Navy also rotationally deploys P-8A Poseidon maritime patrol and reconnaissance aircraft to Singapore; the platform has been an instrumental workhorse for regional maritime domain awareness missions, including over the South China Sea. In the same vein, the Royal Australian Air Force appears to have also been flying P-8A missions from the island city-state.102 Both countries have also consistently supported Singapore’s regional maritime security cooperation initiatives, chiefly through the deployment of international liaison officers to the Information Fusion Centre based in Changi Naval Base,103 which is envisaged to be one of the partner institutions to the Quad’s Indo-Pacific Partnership for Maritime Domain Awareness (IPMDA), which seeks to work with regional partners to respond to, amongst various security challenges, illegal fishing which is rampant in the South China Sea.104

Australian and US access has remained stable, reliable, and not lent to political travails [….] notwithstanding the fact that Singapore is not a formal US treaty ally.

Broadly speaking, Singapore’s defence and security engagements with Australia and the United States have been comprehensive, covering many areas such as joint training, access to military facilities, logistics support, intelligence exchange and information sharing, defence industrial cooperation as well as dialogues and exchanges across holistic military domains, including cyber.105 All in all, Singapore’s arrangements with Australia and the United States have generally facilitated the sustainment of their military presence in the region, not least the South China Sea. Australian and US access has remained stable, reliable, and not lent to political travails unlike the case of the Philippines, especially under the then Duterte administration — this notwithstanding the fact that Singapore is not a formal US treaty ally.106

Any further expansion of this access would have to be carefully deliberated, predicated on both Singapore’s national interests and those of Australia and the United States. Singapore’s caution was reflected in November 2020 when then US Secretary of Navy Kenneth Braithwaite proposed the establishment of the 1st Fleet tailored for Indo-Pacific operations, with Singapore identified as one possible basing location. Soon after, the Singapore Ministry of Defence released a curt statement emphasising the pre-existing standing arrangement to deploy up to four littoral combat ships to the island city-state on a rotational basis, and that “no further requests from or discussions” with Pentagon had been made on additional deployments.

Singapore’s approach to engaging Australia and the United States

Overall, dealing with the PRC’s maritime coercion falls neatly into the broader quest to maintain a rules-based order in the region. To that end, maintaining a viable, sustainable extra-regional security presence is crucial. Following the “verbal war” with the PRC over the South China Sea issues in late 2016, Singapore has sought to avoid similar megaphone diplomacy with Beijing and instead chosen to act more and talk less. Aside the often bland, standard language expressing support for international law, especially the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) in the official discourse, the island city-state has elected to push initiatives that sought to entrench not only the rule of law in practice but also, an extra-regional military presence that is believed to promote peace and stability in the South China Sea.

The 2019 Protocol of Amendment to the 1990 MOU, for example, extends the US forces’ access to Singapore’s military facilities for another 15 years.107 That same year, a bilateral agreement was signed establishing a permanent Republic of Singapore Air Force training detachment in Guam,108 a development which ought to be seen in the light of the PRC military build-up including an expanding missile arsenal believed capable of striking far-flung key US military hubs.109 In an apparent snub to the PRC’s suggestion to exclude or limit foreign military exercises in the Single Draft Negotiating Text of the proposed Code of Conduct for the South China Sea, ASEAN conducted its inaugural maritime exercise with the United States in September 2019 — and Singapore had a role to play in it as the ASEAN chair during the time of its announcement at the 12th ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting, chaired by the country, in October 2018.

Also in late 2019, the Republic of Singapore Navy signed an MOU with Australia’s Maritime Border Command on sharing and protection of information related to White Shipping.110 Then, in 2020, Singapore and Australia elevated the 2016 MOU on Military Training and Training Area Development in Australia to a 2020 Treaty on Military Training and Training Area Development, which allows both countries to jointly expand and develop SWBTA and the new Greenvale Training Area in Queensland, which would also facilitate the deepening of bilateral defence cooperation including joint exercises.111

Finally, Singapore’s reaction to the announcement of the Australia-United Kingdom-United States trilateral partnership (AUKUS) in September 2021 was also positive.112 Altogether, even while not openly endorsing the Indo-Pacific visions or strategies espoused by Australia and the United States, Singapore has preferred to facilitate and support these associated endeavours through concrete measures. However, it was not until recent years that many of these initiatives have decidedly fallen within the realm of defence and security.

Conclusion

Over the decades, Singapore has already cultivated a set of comprehensive and deep defence and security partnerships with Australia and the United States. While not particularly designed for addressing maritime coercion or “grey zone” challenges per se, these partnerships sought to uphold the rule of law and promote peace and stability in the region, including the South China Sea. Singapore’s recent new initiatives look set to further cement these relations with Australia and the United States. For example, the recent Submarine Staff Talks between the Singapore and US navies herald further cooperation and integration of their undersea forces.113 The Australia-Singapore agreement signed in July 2021 to expand SWBTA to host 14,000 SAF personnel for 18 weeks at a time annually until 2046,114 also looks set to further entrench Canberra’s role as one of the key defence partners of choice for Singapore.

What is needed going forward, would be cooperative initiatives aimed at boosting regional resilience against coercion. Singapore’s role in supporting the IPMDA would represent a contribution towards building regional resilience within the maritime domain. However, this is not sufficient in itself — building general resilience that facilitates the exercise of agency and strategic autonomy against coercion should also be seen as an equally important agenda. In this case, the 2019 Framework to Strengthen Infrastructure Finance and Market Building Cooperation signed between Singapore and the United States, which seeks to promote sustainable infrastructure financing in the Indo-Pacific region through market-oriented, private-sector investments,115 is noteworthy. More such non-military, holistic approaches towards enhancing regional resilience against coercion can be potential areas to explore by Singapore, Australia and the United States. It also alleviates the pressure on Singapore given its bid to cultivate buoyant, primarily economics-driven relations with the PRC on the one hand, and to contribute towards the maintenance of regional peace and security in conjunction with long-standing partners such as Australia and the United States.

5. A Vietnamese view of maritime security cooperation with the Australia-US alliance

Lan-Anh Nguyen, Diplomatic Academy of Vietnam

Introduction

The South China Sea in 2022 appears calm for Vietnam since there have been no major incidents like the oil rig incident in 2014 or the seismic survey in the Vanguard Bank in 2019. However, the rise in the PRC‘s naval presence has led to an increase in the PRC’s sea and air exercises, along with a proliferation of restrictions on maritime traffic, aviation and littoral states’ legal rights in the exclusive economic zone and continental shelf.116 For the first time, the PRC conducted a nearly two-week military drill outside the Gulf of Tonkin’s mouth in parts of Vietnam’s exclusive economic zone in March 2022.117 The PRC held another military drill within 12 nautical miles of Woody Island (Phú Lâm), a feature in disputed sovereignty with Vietnam, in the South China Sea in June.

Over half of the South China Sea remains subject to a unilateral and illegal fishing ban from 1 May to 31 August each year by the PRC, including partial exclusive economic zones (EEZ) of Vietnam and the Philippines. The PRC enacted a new Coast Guard Law authorising the use of force against foreign military, government and commercial vessels violating the PRC’s jurisdictional waters, including the disputed maritime zones.118 With the promulgation of the new Coast Guard Law, the Chinese Coast Guard, which has more and bigger ships than other navies in the region, will have a greater “legal basis” to coerce and prevent legitimate fishermen in coastal nations, including Vietnamese, from fishing in their countries’ exclusive economic zones. In addition, through the use of grey zone tactics, i.e., limiting maritime activities between peace and war, harassing below the threshold of conventional warfare, and creating ambiguity between civil and military acts,119 the PRC continues to successfully change the status quo unilaterally, de facto controlling the South China Sea and preventing littoral states from exercising their legitimate maritime rights.

The People’s Republic of China continues to successfully change the status quo unilaterally, de facto controlling the South China Sea and preventing littoral states from exercising their legitimate maritime rights.

The PRC projects its maritime claims contrary to UNCLOS, including Vanguard Bank (Bãi Tu Chính), a submerged feature on Vietnam’s continental shelf. It has been reported that the PRC’s law enforcement forces were present at Vanguard Bank for 142 days in 2020 alone.120 At the same time, maritime militia forces harass Vietnam’s maritime economic activities within Vietnam’s exclusive economic zone, as designated by UNCLOS. PRC forces are expanding geographically, getting deeper and deeper towards Vietnamese coasts, and extending from the seabed to the airspace; and their activities have become increasingly diverse, ranging from resource-related activities to marine scientific research and law enforcement.121 In April and June 2020, the PRC named 55 underwater mountains and ridges in the continental shelf of Vietnam in the South China Sea and 50 underwater features near the Sekaku/Diaoyu Island in the East China Sea.122 Dangerous manoeuvres were also reported between a PRC J16 jet and RAAF P8 maritime aircraft in the South China Sea in June 2022.123 AMTI-CSIS statistics showed that, since 2019, PRC survey vessels in the South China Sea have been deployed four times.124

This development will certainly concern countries in the region, including Vietnam, leading them, on the one hand, to improve their self-defence capabilities and, on the other, to expand international cooperation in order to maintain and protect the rules-based order in the South China Sea. Given its geostrategic characteristics, particularly from its history of being a victim of strategic competition between great powers, maintaining an independent and self-reliant foreign policy, maintaining a peaceful environment and stability for economic development, and maintaining open foreign relations are critical objectives of Vietnam’s foreign policy. Like many other countries, Vietnamese nationalists have always demanded that the government take stronger measures to protect their interests.

Following the conflict in Ukraine, the practice of great powers arbitrarily interpreting international law and infringing upon the sovereign and territorial integrity of another country has become more and more prevalent. Vietnam is also concerned that the conflict in Ukraine could ripple through Asia and directly or indirectly affect Vietnam, that the South China Sea could once again be a target of the illegal use of force and that it is necessary to closely monitor the PRC’s movements in order to avoid being passive and unprepared.125

Vietnam’s interests in capacity-building and domain awareness

During recent years, Vietnam, Australia and the United States have engaged in several maritime cooperation activities, focusing primarily on three areas: port visits, capacity building, and raising maritime domain awareness.126 The purpose of port visits is not only to promote cooperation between navies but also to build trust, promote cultural exchange and facilitate both people-to-people and high-level contacts.127 As part of the series of events held during the IPE Task Group’s visit, a maritime security workshop was organised by Vietnam and Australia. The workshop covered a wide range of contemporary maritime security issues, including frameworks for cooperation and dispute resolution, grey zone tactics, maritime law enforcement and the use of force, as well as advancing a common understanding of international law, including UNCLOS, by maritime security policymakers and maritime operators.128

In terms of capacity building, the Vietnam Coast Guard has undertaken several key projects, including refurbishing two former US Coast Guard cutters under the Excess Defense Articles program and purchasing MetalShark patrol boats. USCGC Morgenthau, a Hamilton-class vessel (the second-largest class in the US Coast Guard), was transferred to the Vietnamese Coast Guard in 2017 and commissioned as CSB 8020. USCGC Midgett, the last member of the US Coast Guard’s endurance fleet to be decommissioned, was transferred and renamed CSB 8021 in 2021.129 From 2017 to 2021, a total of 24 Metal Shark high-speed patrol boats were sold to Vietnam. These are milestone projects to improve Vietnam’s law enforcement capacity at sea, particularly in light of the increasing number of incidents and the expansion of grey tactics in the South China Sea.130

Training in English is at the core of capacity-building cooperation between Vietnam and Australia. Over the past 20 years, more than 2,600 Vietnamese soldiers and officers have received English language training from the Australian Defence Force (ADF) and over 500 Vietnamese military personnel have also completed advanced training in Australia, including 170 officers with master’s degrees.131 In addition, Australia conducts maritime security and Law of the Sea exchanges and training with the Vietnam People’s Navy during annual ship visits.

Cooperative activities in maritime security between the United States, Australia and Vietnam complement one another. Australia focuses on soft skills, while the United States provides defence articles and equipment. Despite this, the level of cooperation has not yet been able to keep up with the expansion of maritime incidents into untraditional spaces, such as cyber, undersea, air and outer space. Furthermore, given that the majority of tensions in the South China Sea result from grey zone tactics, maritime domain awareness will be critical for any law enforcement agency to be able to respond in a timely manner. As a result, building contacts, and sharing information, including real-time satellite images and surveillance flight data, as well as training tactical skills and operational tactics, techniques and procedures would further assist Vietnam in improving its maritime law enforcement capability.

In addition to the existing cooperation mechanism, the Indo-Pacific Maritime Domain Awareness Initiative (IPMDA) announced at the Quad Summit in May 2022 also offers a better coordination framework for addressing common concerns and promoting cooperation on maritime security of Vietnam and other countries in the region. For the first time, the issue of maritime militias was mentioned in the Quad’s members’ leaders’ statement. It was also mentioned in US Defense Secretary Austin’s speech at the Shangri-La Dialogue that efforts would be made to respond to grey zone tactics in the South and East China Seas. They are important ideas and should be converted into concrete cooperative initiatives and projects to maintain a rules-based order in the South China Sea.

Vietnam’s emerging priorities in the South China Sea

With the PRC’s grey zone tactics increasingly expanding, not only in the military field, but also in the areas of cyber security, economics and geopolitics — and not only on land and at sea, but also in the air, cyberspace and outer space — joint efforts to maintain and protect the rules-based order will become even more critical.132 Maritime security cooperation and the development of Vietnam’s capacity to protect its legitimate rights and interests are still the priorities and are well received. In this regard, the goal of maritime capacity-building cooperation should be to enhance the Coast Guard’s response capability, while also taking into account monitoring capability in new and non-traditional domains.

The goal of maritime capacity-building cooperation should be to enhance the Coast Guard’s response capability, while also taking into account monitoring capability in new and non-traditional domains.

In the quest for new and feasible areas of cooperation, cooperation in marine environment protection and conservation, marine scientific research, and transferring of ocean management technologies should be emphasised to address the pressing issues of increasingly degraded and polluted marine environments and marine debris. Likewise, at the COP26 UN Climate Change Conference, Vietnam committed to achieving net-zero emissions by 2050. Vietnam also issued a strategy for the sustainable development of its marine economy to 2030, with a vision to 2045.133 Cooperation in the field of marine economics towards green and sustainable development, therefore, should be focused on and promoted at both bilateral and minilateral levels, including the participation of the PRC.

On the legal front, despite a battle of diplomatic notes at the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf, non-compliance with the 2016 Arbitral Award remains the greatest obstacle to upholding the rules-based order in the South China Sea. Therefore, there is a need for joint efforts to highlight arbitrary interpretations of international law and UNCLOS, as well as the application of grey zone tactics that undermine the rules-based order. Meanwhile, the parties may consider imposing sanctions on individuals and organisations involved in violations in order to increase the risk of illegal activity.134

Furthermore, Australia and the United States may consider multilateral and minilateral cooperation with countries with similar cooperation needs such as Japan and India, in addition to bilateral cooperation — for example, training for law enforcement officers, marine scientific research, and marine environmental protection, particularly cooperation in joint patrolling and tabletop exercises.

Conclusion