Executive summary

- US investment in Australia has declined for three consecutive years and Australia has underperformed peer economies in attracting US capital.

- Global foreign direct investment (FDI) flows decreased by 38 per cent in 2020 to only 1 per cent of world GDP, their lowest since 2005.

- For the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) area, FDI inflows fell by 51 per cent. Australia’s experience was in line with the rest of the OECD, with a 48 per cent decline in inward FDI transactions.

- But US FDI transactions in Australia underperformed, with an inflow of just $1.1 billion in 2019, followed by an outflow of $12 billion in 2020, the first such outflow since 2005.

- The total value of two-way investment between Australia and the United States was just under $1.8 trillion in 2020, down from a record $1.85 trillion in 2019.

- The decline was driven by an $84 billion decline in the value of US investment in Australia. Australian investment in the United States rose by nearly $27 billion.

- The stock of US foreign direct investment in Australia fell by $25 billion, while Australian FDI in the United States rose by nearly $22 billion in 2020.

- The value of Chinese FDI transactions in Australia across 2019 and 2020 was greater than from the United States, +$6 billion in total for China versus -$11 billion for the United States despite the fact that China’s global outward investment fell to a 13-year low in 2020.

- Data from the US Bureau of Economic Analysis shows that US FDI in Australia on a historical cost basis peaked in 2014 at US$177.4 billion and fell from US$169.7 billion in 2017 to US$162.4 billion in 2019, a decline of 4.3 per cent over the two years since the passage of President Trump’s Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) in 2017.

- On the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) measure, US FDI in Australia between 2017 and 2019 underperformed that in Australia’s peer economies and regions, including Canada, the United Kingdom, New Zealand, the euro area and the Asia-Pacific region excluding Australia.

- The biggest decline in US investment in Australia in 2020 was due to a $43 billion decline in portfolio investment in debt securities and an associated $33 billion decline in financial derivatives hedging these and other exposures.

- This most likely reflects US investors liquidating debt securities to raise and repatriate cash during the pandemic. At least some of this outflow will likely be reversed in subsequent years.

- The one bright spot in US investment in Australia in 2020 was portfolio investment in equity securities, which saw an inflow of $9 billion, the largest inflow since 2017, which partly offset the outflow in debt securities.

- The downturn in foreign investment in Australia, including from the United States, can be explained by the pandemic downturn in global investment, a reduced Australian international borrowing requirement, more competitive US tax settings and an increase in regulation and regulatory uncertainty arising from Australia’s foreign investment review process. However, US investment in Australia still underperformed in relative terms.

- The United States will become less competitive in attracting foreign capital relative to Australia as a result of the Biden administration’s proposed increase in the US corporate tax rate. However, the Biden tax changes will also reduce investment by US firms globally, so the implications for US investment in Australia are ambiguous.

- An agenda for increasing foreign, including US, investment in Australia, includes corporate tax reform, streamlining the regulation of foreign direct investment and re-opening the borders to facilitate due diligence on cross-border deals.

Introduction

The Australia-US bilateral investment relationship has traditionally been Australia’s single most important source of foreign financing for domestic investment and economic growth. The relationship provides Australian borrowers with access to the world’s deepest and most liquid capital market. It also complements the strong diplomatic and security relationship between the two countries.

Yet the bilateral investment relationship has shown significant weakness over the last three years and Australia has underperformed peer economies in attracting US capital, even before the onset of the pandemic in 2020. The pandemic-induced downturn in global investment and cross-border capital flows, excess saving and weak investment demand in Australia, US tax changes and Australia’s regulation of foreign investment are all potentially implicated in this weakness. Although the pandemic and President Trump’s tax changes are likely to be mainly temporary influences, Australian policymakers need to pay increased attention to policy settings that may be deterring US investment in Australia, even as some of these temporary negative influences moderate.

The pandemic led to substantial repatriation of investment globally, as international investors sold assets to raise cash and limit risk exposure. Global FDI flows decreased by 38 per cent in 2020 to only 1 per cent of world GDP, their lowest since 2005. For the OECD area, FDI inflows fell by 51 per cent.1 Australia’s experience was in line with the rest of the OECD, with a 48 per cent decline in inbound foreign direct investment transactions. But US FDI transactions in Australia saw an outflow of $12 billion in 2020 after only $1.1 billion in new direct investment in 2019.2 This was the first outflow of US direct investment since 2005; then the result of a single large corporate restructure.

Apart from the pandemic and its implications for Australian domestic saving and investment, President Trump’s corporate tax cut in 2017 has likely weighed heavily on US investment in Australia by making Australia a less attractive investment destination on a relative basis.

Over the same period, Australia has seen a dramatic reduction in its international borrowing requirement. An increase in domestic saving and weak domestic investment have resulted in record current account surpluses as a share of GDP, reducing the need for foreign capital inflow. Treasury expects the current account to remain in surplus until 2022-23. The surplus for 2020 was $49 billion, a $36 billion increase on the previous year.

The financial account recorded a net capital outflow of $154 billion in 2020 compared to an inflow of $5 billion in 2019. If the US share of that net capital outflow were the same as the average US share of the stock of foreign investment between 2001 and 2017 at around 26 per cent, then we would expect a reduction in US investment of around $41 billion. But US investment transactions in Australia saw outflows of $102 billion in 2020, accounting for 66 per cent of the overall net capital outflow. So, not all of the weakness in US investment can be attributed to a simple reduction in Australia’s international borrowing requirement.

The outflow of US investment in 2020 mostly took the form of a reduction in portfolio investment in debt securities and associated derivatives hedging those investments, as US investors sold overseas assets to raise cash during the pandemic. However, direct investment transactions and the stock of US FDI in Australia as a share of GDP both fell in 2020 for the third straight year.

Apart from the pandemic and its implications for Australian domestic saving and investment, President Trump’s corporate tax cut in 2017 has likely weighed heavily on US investment in Australia by making Australia a less attractive investment destination on a relative basis. While the new Biden administration will again revamp the US corporate tax system, it remains to be seen how this change will affect US corporate investment, including US corporate investment abroad. The United States will become a less competitive destination for investment, making Australia more attractive on a relative basis, but US corporates can be expected to reduce their investment both at home and abroad in response to a higher overall tax burden.

Australia could improve its policy settings with respect to inbound investment, which could help underpin economic recovery, especially if Australia once again becomes a net borrower internationally. The federal government’s 2021 Budget implements some of the recommendations of a report by the Australia as a Financial and Technology Centre Advisory Group, which will help make Australia a more attractive investment destination.

The closure of Australia’s borders has also impeded the ability of foreign investors to do due diligence on Australian acquisitions.

However, Australia has the third-highest tax burden on capital income among 30 OECD countries, pointing to the continued need for corporate tax reform.3 Australia’s increased screening of FDI and associated increased application fees for foreign investors, while unofficially targeted at China, weighs more heavily on the United States as the larger overall investor in Australia because of its non-discriminatory application. The closure of Australia’s borders has also impeded the ability of foreign investors to do due diligence on Australian acquisitions.

A renewed focus on corporate tax reform and international tax rules in Australia would attract more inbound investment, including from the United States. Both Australia and the United States could advocate for a corporate cash flow tax with full expensing of investment in the context of multilateral tax negotiations over a new global minimum corporate tax. Under this approach, taxes are only charged when profits are moved out of a business and not when a business reinvests its profits.4 Grubert and Altshuler have suggested a minimum tax on foreign earnings of US companies that fully exempts the cost of new investment.5

Streamlining the regulation of inward FDI on the part of established investors to reduce delays and uncertainty and lowering the burden of application fees for foreign investors could also benefit foreign investment. My Foreign Investment Uncertainty Index found uncertainty doubled in 2020 relative to 2019,6 although has moderated in the first quarter of 2021.

A progressive, risk-based re-opening of Australia’s borders and increase in net overseas migration relative to pre-pandemic levels, as recommended in my United States Studies Centre (USSC) report Avoiding US-style demographic stagnation,7 would also help facilitate due diligence on FDI transactions and given that immigration is highly complementary to cross-border trade and investment.

The bilateral investment relationship: the stock perspective

The bilateral investment relationship can be viewed from the perspective of both stocks and flows. Stocks measure the accumulation of foreign investment and reflect valuation effects from movements in exchange rates and prices, while flows measure underlying transactions at a given point in time.

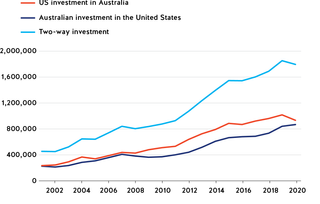

In stock terms, the total value of two-way investment between Australia and the United States was just under $1.8 trillion in 2020, down from a record $1.85 trillion in 2019 (Figure 1). The decline was driven by an $84 billion decline in the value of US investment in Australia. Australian investment in the United States rose by nearly $27 billion.

Figure 1. Bilateral investment relationship — stock ($m)

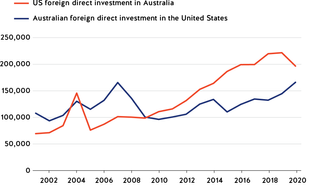

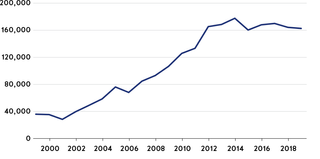

The stock of US foreign direct investment in Australia fell by $25 billion, while Australian FDI in the United States rose by nearly $22 billion (Figure 2). The level of direct Australian investment in the United States remains below that of the United States in Australia but is once again converging in value. Data from the US Bureau of Economic Analysis8 shows that US FDI in Australia on a historical cost basis (that is, excluding subsequent valuation changes) peaked in 2014 at US$177.4 billion and fell from US$169.7 billion in 2017 to US$162.4 billion in 2019, a decline of 4.3 per cent over the two years since the passage of the US Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Foreign direct investment relationship — stock ($m)

Figure 3. US direct investment in Australia ($m), historical cost basis

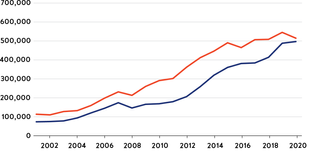

US portfolio investment in Australia fell by $35 billion in value terms, while Australian portfolio investment in the United States increased by $10 billion (Figure 4). Repatriation of US portfolio investment, as US investors sought to raise cash during the pandemic, together with the unwinding of associated hedging through financial derivatives, were the main sources of weakness in the overall investment relationship in 2020.

Figure 4. Portfolio investment relationship — stock ($m)

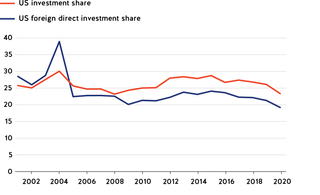

The US share of the stock of total foreign investment in Australia has been declining for three consecutive years, while the US share of the stock of FDI has now declined for two years (Figure 5).

Figure 5. US share of foreign investment in Australia — stock (%)

The bilateral investment relationship: the flow perspective

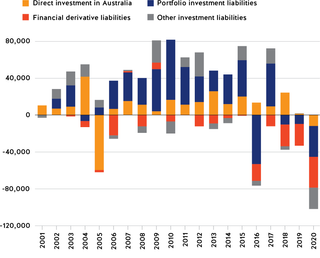

With outflows of just over $100 billion, 2020 was a bad year for US investment flows into Australia. This was the third consecutive year of such outflows. The reduction in US investment notionally accounted for 66 per cent of the overall reduction in Australia’s net external financing requirement in 2020. Over the last three years, Australia has lost nearly $150 billion in US investment.

In terms of FDI, US investment in Australia saw an outflow of $12 billion in 2020, the first outright decline in US FDI in Australia since 2005, which was then the result of a single large corporate restructuring. The year before (2019) was barely positive, with just over $1 billion in investment. The value of Chinese FDI transactions in Australia across 2019 and 2020 was greater than from the United States, +$6 billion in total versus -$11 billion for the United States. This is despite China’s global outward FDI falling to a 13-year low in 2020.9 The weakness in US direct investment in Australia in 2020 was offset by increased transactions from Japan (+$8.9 billion), France (+$14.2 billion), New Zealand (+$1.2 billion) and Ireland (+$1.5 billion) compared to 2019, highlighting the underperformance of US investment in Australia relative to that from other peer economies.

Figure 6. US investment transactions in Australia ($m)

Several factors likely account for the weakness in FDI in recent years. During the pandemic, it is likely US parents were borrowing from their Australian affiliates to raise cash. Australian affiliates are also likely to be paying off loans from their US parents. President Trump’s tax reforms mean that interest deductions on loans to US subsidiaries are less valuable. To the extent that US affiliates in Australia have been losing money or paying more in dividends to their US parent than income received, this could be expected to weigh on re-invested earnings. A decline in re-invested earnings accounts for 58 per cent of the decline in US FDI in Australia in 2020.

The weakness in US investment in Australia was reflected in public market cross-border mergers and acquisitions (M&A) transactions, a subset of FDI, where foreign bidder activity was at a decade low in 2020, continuing a three-year downward trend. Less than half of proposed foreign acquisitions were successful, the lowest success rate in 10 years.10 Of four large prospective deals with a US bidder in 2020, only one was completed and it was less than half the size of one large deal with a Chinese bidder which was successfully concluded (Table 1).

Table 1. Public cross-border mergers and acquisitions in 2020

|

Target |

US bidder |

Type |

Status |

Final transaction value ($m) |

|

Australian Unity Office Fund |

Starwood Capital |

Off-market takeover |

Withdrawn |

485 |

|

3P Learning |

IXL Learning |

Scheme |

Withdrawn |

188 |

|

Pioneer Credit Limited |

Robin BidCo |

Scheme |

Withdrawn |

120 |

|

National Veterinary Care Ltd |

Aus Vet Owners League |

Scheme |

Completed |

249 |

|

Target |

Chinese bidder |

Type |

Status |

Final transaction value ($m) |

|

Cardinal Resources |

Shandong Gold Mining |

Off-market takeover |

Successful |

565 |

The biggest decline in US inward investment transactions was due to a $43 billion outflow of portfolio investment in debt securities and an associated $33 billion outflow in financial derivatives hedging these and other exposures. This most likely reflects US investors liquidating debt securities to raise and repatriate cash during the pandemic. At least some of this outflow will likely be reversed in subsequent years. The one bright spot in US inward investment transactions was portfolio investment in equity securities, which saw an inflow of $9 billion, the largest inflow since 2017, which partly offset the outflow in debt securities.

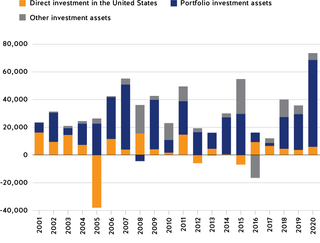

Australian investment transactions in the United States rose strongly in 2020, driven largely by portfolio investment in equity and debt securities, showing the largest flows into the United States since 2001. (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Australian investment transactions in the United States ($m)

Portfolio outflows reflect a growing share of superannuation assets being invested abroad as domestic capital markets become increasingly saturated with superannuation saving. The share of superannuation assets invested in Australia has been on a declining trend, from more than 90 per cent in the late 1980s and early 1990s, to 82 per cent more recently.11

Australian direct investment in the United States rose from $3.4 billion in 2019 to $5.6 billion in 2020 but below that seen in previous years. Australia’s overall direct investment transactions abroad were little changed in 2020, so Australian FDI in the US outperformed. On a flow basis, Australia has been a bigger overall investor in the United States over the last three years than the United States has been in Australia, including direct investment.

How does US foreign direct investment in Australia compare?

Overall US FDI outflows were unchanged in 2020 versus 2019 at around $US94 billion.12 US FDI in Australia can be benchmarked against other countries and regions using US data that measures FDI positions on a consistent basis (see Table 2). For reference, Table 2 also shows the change in the current account balance over the same period as a proxy for the change in the country or region’s overall external financing requirement.

Table 2. US foreign direct investment, selected countries/regions, 2017-19

|

|

% change US FDI |

Change in current account balance (ppts of GDP) |

|

Canada |

8.3 |

0.7 |

|

Europe |

-2.3 |

-0.7 |

|

United Kingdom |

4.5 |

0.7 |

|

Asia-Pacific |

1.8 |

- |

|

Australia |

-4.3 |

3.2 |

|

New Zealand |

-3.0 |

-0.4 |

|

Asia-Pacific ex-Australia |

3.1 |

- |

Over the two years 2017-19, growth in US FDI in Australia significantly underperformed peer economies such as Canada, the United Kingdom, New Zealand and regions such as Europe and the Asia-Pacific. This suggests recent weakness in US direct investment in Australia is specific to the Australia-US investment relationship, rather than being driven by weakness in US FDI more broadly. While Australia also had the largest reduction in its implied net external financing requirement as measured by the change in the current account balance as a share of GDP, both Canada and the United Kingdom also saw reductions in their external financing requirements while still enjoying strong growth in US FDI.

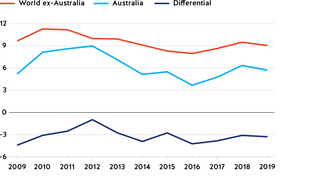

Returns to US foreign direct investment in Australia

It is possible to calculate the average return on US FDI in Australia by dividing income without current cost adjustment earned by US multinational enterprises (MNE)’s in Australia by their FDI position.13 This can be compared with average returns on US FDI abroad ex-Australia (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Average return on US foreign direct investment abroad (%)

The return on US FDI in Australia in 2019 averaged just under 6 per cent, which is in line with the return to FDI in developed economies.14 This is a little lower than the 9 per cent return seen around the peak of the mining boom earlier in the 2010s. While the return to FDI in Australia is lower than for US FDI in the rest of the world ex-Australia, this is to be expected given the high returns available in some developing economies relative to Australia’s developed country peers. There is no clear long-term trend in the return differential between US FDI in the rest of the world and US FDI in Australia that could explain the recent weakness in US investment in Australia, which suggests any weakness is due to changes in post-tax, not pre-tax returns.

Factors explaining recent weakness in US investment in Australia

Several factors can help explain the recent weakness in US investment in Australia. Some are temporary and can be expected to see US investment in Australia recover in the years ahead. Other factors are potentially ongoing but are amenable to being addressed through public policy.

The pandemic. The global economic downturn associated with the pandemic has weighed heavily on both business investment and cross-border capital flows. The pandemic has made due diligence on cross-border transactions more difficult. In Australia, the lowering of the monetary threshold for Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB) scrutiny to zero resulted in significant delays in the foreign investment screening process. The lower threshold was introduced due to concerns the pandemic might lead to the opportunistic foreign acquisition of distressed Australian firms, in particular, by China. In the event, China’s global FDI fell to its lowest in 13 years in 2020 and has been on a declining trend since 2016 due to its own controls on outbound FDI.15 Australia also introduced a new national security test from 1 January 2021, which likely raised uncertainty while the legislation and associated regulations were under consideration by parliament during 2020. While these factors help explain the overall downturn in inward investment, they do not explain the relative underperformance of US investment specifically.

External financing requirement. As already noted, from the end of 2017 to the middle of 2020, Australia’s current account saw a dramatic seven percentage point turnaround, from a deficit of 3.5 per cent to a surplus of 3.5 per cent of GDP, and 3.6 per cent of GDP in Q1 2021, the largest surplus on record. This implies a dramatic change in Australia’s external financing requirement, from a net borrower internationally to a net lender. The reduced need for foreign capital inflow reflects both an increase in domestic saving and weakness in domestic investment. The current account balance is cyclical and can be expected to return to a deficit as the economy recovers, assuming it can once again grow close to the trend. Treasury’s 2021 Budget assumes an eventual return to a deficit. However, the increase in the Superannuation Guarantee rate from 1 July 2021 and in subsequent years will contribute to Australia’s excess saving problem, all else equal.

Foreign direct investment from other jurisdictions is not a perfect substitute for US investment and may result in a loss of some of the benefits associated with access to US managerial talent, supply chains, intellectual property and innovation.

While the reduction in the overall financing requirement can help explain a reduction in US investment in absolute terms, it cannot explain a reduction in US investment in relative terms. While overall foreign capital inflows are mostly fungible, the benefits of FDI tend to be investor-specific. FDI from other jurisdictions is not a perfect substitute for US investment and may result in a loss of some of the benefits associated with access to US managerial talent, supply chains, intellectual property and innovation.

FDI regulation and uncertainty. Australia has the fifth most restrictive regulatory regime for FDI based on the OECD’s FDI Restrictiveness Index16 and continues to impose additional requirements on foreign investors, including a new national security test and increased application fees that act as a tax on inward investment. The Productivity Commission has quantified the cost of some of these regulations in terms of lost investment.17

While not targeted at the United States specifically, regulatory uncertainty and costs can still be expected to weigh on US investment. The Australia-US Free Trade Agreement provides significant relief from this burden relative to non-FTA countries, but inward FDI from the United States can still trigger FIRB scrutiny and consequent delays, costs and uncertainty, particularly if an entity in a non-FTA jurisdiction is involved in the transaction. In the case of global transactions, Australian subsidiaries will sometimes be off-loaded to Australian buyers, if only temporarily, to avoid FIRB delays affecting the global transaction. A recent PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) report highlights some of the ways in which US investment is caught, despite raising few policy issues, and proposes measures to streamline approvals.18

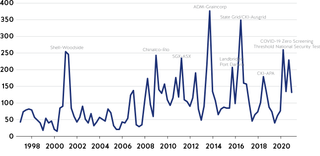

The USSC’s Foreign Investment Uncertainty Index found a near doubling in policy-related uncertainty over 2020 compared to the average for 2019, largely due to the reduction in FIRB screening thresholds in response to the pandemic and the new national security test.19 The first quarter of 2021 saw a 60 per cent reduction in uncertainty to its lowest level since the onset of the pandemic, as the monetary thresholds for investment screening reverted to normal from 1 January and more clarity was provided around the operation of the new test. The latest update to the Index is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9. Foreign Investment Uncertainty Index — Australia

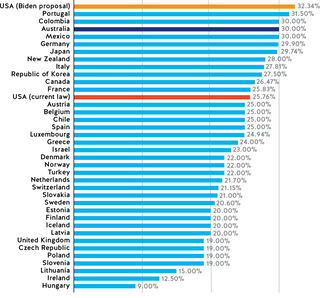

Taxation. The passage of President Trump’s Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) at the end of 2017 was always expected to weigh on US investment in Australia by cutting the US federal corporate tax rate from 35 per cent to 21 per cent, below Australia’s rate of 30 per cent, and closer to the OECD average (Figure 10). This left Australia’s corporate tax rate among the highest in the OECD.

Figure 10. Statutory corporate tax rates in the OECD (combined national and sub-national rates), 2022

By increasing the after-tax return on investment in the United States, the corporate tax cut could be expected to have negative spillovers on investment in the rest of the world, including Australia, to the extent that any resulting increase in US investment is financed from abroad (the United States runs a current account deficit). In the event, the investment response was lacklustre and the United States has experienced a decline in inward FDI ‘driven by the corrosion of US openness to trade and global cooperation’ under the former Trump administration.20

The TCJA changed US corporate taxation from a worldwide system of taxation with deferral to a territorial system. US MNC’s could previously defer the realisation of income for tax purposes by not repatriating income from controlled foreign corporations (CFCs) to their US parents, which tended to erode the US corporate tax base. The TCJA excluded dividends from CFCs from taxable income but also included provisions to limit the incentives for profit-shifting. These changes were widely expected to induce repatriation of foreign earnings after 2017 when the legislation was passed.

While Australia’s relative competitiveness as an investment destination will improve under the plan, US corporates will likely reduce their investment both at home and abroad in response to the higher corporate tax burden.

The Biden administration’s Made in America Tax Plan will increase the corporate tax burden and penalise both the domestic and foreign activity of US firms, reducing both domestic and global investment. The Biden plan will likely see a significant restructuring of the international ownership and operations of US firms away from US ownership and in favour of foreign ownership.21 The Biden tax plan thus has mixed implications for US investment in Australia. While Australia’s relative competitiveness as an investment destination will improve under the plan, US corporates will likely reduce their investment both at home and abroad in response to the higher corporate tax burden.

The Biden administration has also proposed a global minimum corporate tax of 15 per cent as part of OECD-sponsored multilateral tax negotiations. This is a lower rate than the administration’s original proposal of 21 per cent, which was supported by the Australian Government. As high corporate tax jurisdictions, the United States and Australia have a common interest in reducing international tax competition. By narrowing corporate tax differentials in favour of high tax jurisdictions, proposals for a global minimum tax and other measures could increase FDI to Australia. According to one estimate, the complete elimination of corporate tax differentials within the OECD at a common rate of 12.5 per cent would see a 20 per cent increase in inward investment in Australia due to its high tax status, but at the expense of other small open economies with currently lower corporate tax rates.22 As the analyst noted, the OECD’s proposed corporate tax reforms ‘would punish the world’s best-performing economies with regard to economic freedoms, trade and investment openness and the rule of law.’23 As much as 40 per cent of global FDI moves through these low-tax investment hubs.24 The current proposals for a global minimum corporate tax would adversely affect investment through these hubs.

An agenda for increasing US investment in Australia

As Australia recovers from the pandemic, domestic investment will recover, the external financing requirement will increase and once again see net capital inflows that have historically underpinned Australia’s economic growth. While foreign capital inflows are to some extent fungible, this is not true of foreign direct investment. FDI is accompanied by transfers of managerial skill, entrepreneurial talent, intellectual property and access to firm-specific global supply chains. US direct investment in Australia is not a perfect substitute for other forms of foreign capital inflow. We should therefore be concerned about a shift in the composition of foreign capital inflows away from the United States.

Australia’s federal and state governments devote significant resources to investment attraction and facilitation, not least in the United States. However, these efforts are often undermined by domestic policy settings that are unfriendly to foreign capital. Marketing efforts abroad need to be matched by improved domestic policy settings at home.

The 2021 Federal Budget contained some measures that can be expected to attract increased foreign investment, including the establishment of a fast-track process to provide investors with greater certainty around the tax implications of large investments, finalising the implementation of the Corporate Collective Investment Vehicle regime and establishing a more efficient licensing regime for foreign financial service providers. These measures are consistent with the recommendations of a report by the Australia as a Financial and Technology Centre Advisory Group.25 These changes will help offset some of the other factors weighing on foreign investment.

Australia can further improve its attractiveness to foreign capital in general and US capital more specifically through the following reform agenda.

Corporate tax reform. Reforming the Australian corporate tax system to lower the tax burden on capital in Australia and make Australia’s international tax rules more competitive would help cement any advantage from the Biden administration adopting a tax system that will be one of the least competitive in the OECD and bring Australia’s corporate tax rate into line with the OECD average ex-the United States. Abolishing interest withholding tax on interest paid to foreigners lending into Australia would also attract foreign capital while reducing the budget balance by around $1.2 billion, based on Parliamentary Budget Office estimates.26

Reforming the Australian corporate tax system to lower the tax burden on capital in Australia and make Australia’s international tax rules more competitive would help cement any advantage from the Biden administration adopting a tax system that will be one of the least competitive in the OECD and bring Australia’s corporate tax rate into line with the OECD average ex-the United States.

Adopting the ‘high road’ of domestic corporate tax reform would be preferable to the ‘low road’ of joining the Biden administration’s efforts to cartelise the multilateral tax system in favour of high tax jurisdictions at the expense of small open economies with lower corporate tax rates. While a narrowing in corporate tax differentials within the OECD would likely benefit foreign investment in Australia as a high corporate tax jurisdiction, it will also lead to a less dynamic world and Australian economy by reducing investment globally.

In the context of multilateral negotiations over a global minimum tax, both the United States and Australia could champion a corporate cash flow tax with full expensing of investment as a more investment-friendly alternative to current proposals. Under this approach, a tax liability is only incurred when profits are moved out of a business. If a business reinvests its profit, there is no recognised profit for tax purposes. As well as being less distortionary for investment decisions, a cash flow tax is more simple and less costly to administer and comply with.27

Regulating FDI. Rationalising the foreign investment screening process to capture fewer transactions that are unlikely to raise significant policy issues should be a priority, an issue dramatised by USSC’s Foreign Investment Uncertainty Index. US investment in Australia is unlikely to raise national security concerns and should benefit from a lighter regulatory touch. Ironically, many of the measures put in place to increase scrutiny of foreign acquisitions by non-traditional investors such as China have also hurt inbound investment by traditional partners like the United States because they are implemented on a non-discriminatory basis and because the United States is historically the larger investor.

US investors are likely to be less tolerant of illiberal screening regimes given the relative openness of the United States and opportunities to invest in other economies with fewer restrictions. For example, increased scrutiny of acquisitions by foreign government-linked entities can affect transactions involving US government pension funds. While non-discrimination is an important principle to uphold, investments from the United States raise far fewer national security issues and should therefore benefit from a lighter regulatory touch. Clearly articulating Australian policy on foreign investment and making foreign investment decisions consistent with that policy can help minimise the uncertainty that acts as a barrier to FDI. Corporate restructures involving no change in beneficial ownership should be eligible for a streamlined approval process. A passporting system for established US and other investors in Australia that pre-permissions certain types of acquisitions and that is periodically renewed would be preferable to the current system of reviewing acquisitions on a transaction-by-transaction basis.28

Re-opening the borders. Re-opening Australia’s international borders will facilitate FDI by increasing the ability of prospective foreign bidders to conduct due diligence on transactions involving Australian assets, while also benefiting investment in those sectors reliant on cross-border people flows.