Key takeaways

- The Democratic Party is narrowly favoured to retake the House of Representatives in November’s midterm elections, but Republicans are expected to retain the Senate majority.

- Should Democrats win control of the House, the Trump administration will struggle to deliver on its legislative agenda prior to the 2020 presidential election.

- The midterms will shape the ideological orientation of the Republican Party, which is being remade in President Trump’s image, and the Democratic Party, which is moving further to the left.

- Deepening polarisation between the two major parties will limit the US government’s ability to reach bipartisan compromises on foreign and defence policy, pass the federal budget on time, and avoid government shutdowns.

- After the midterms, Congress is highly unlikely to support – let alone vote in favour of – US re-entry to the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

US President Donald Trump’s ability to achieve legislative successes in the two years before the 2020 presidential election will depend in large part on the results of this year’s midterms. On 6 November, American voters will determine the composition of the 116th Congress. Every seat in the House of Representatives (435) and just over a third of the Senate (35) is at stake. Midterm elections are an important indicator of the national political climate that curb or enhance the power of the president’s party in Congress. If Republicans maintain majorities in the House and Senate, they will continue to pursue core policy priorities such as reducing government expenditure on healthcare and welfare, but remain internally divided between establishment and nationalist wings.1

Republicans currently hold majorities in both chambers of Congress. Due to a very favourable Senate map, Republicans are likely to retain the upper chamber at the midterms.2 But betting markets and pollsters narrowly favour Democrats to flip the House blue.3 Doing so would give Democrats a foothold on power in Washington that is likely to result in government paralysis. This is because an ascendant Democratic Party would have strong incentives to prevent the passage of Republican legislation and use its position to damage President Trump’s standing before the next presidential election.

Whichever party emerges from the midterms with a majority in the House and Senate, the election cycle is important for Australian interests.

Whichever party emerges from the midterms with a majority in the House and Senate, the election cycle is important for Australian interests. The primaries and general congressional election will indicate the extent to which Trump is remaking the Republican Party and the degree to which Democrats are moving to the left on economic and social issues. Polarisation within Congress is likely to increase after the midterms due to the retirement of incumbent Republican moderates and the arrival of new Republican and Democratic members with more hard-line views.

In the last decade, deepening polarisation has affected Congress’ ability to reach the bipartisan compromises required for basic governance, such as passing the federal budget on time and avoiding government shutdowns.4 If Washington becomes more dysfunctional and inwardly distracted, the US government will continue to find it difficult to deliver reliable expenditure for the Pentagon or review Executive Branch nominees in a timely manner. Both parties are becoming more sceptical of multilateral trade agreements, which will continue after the midterms. Consequently, Congress is highly unlikely to support – let alone vote in favour of – US re-entry to the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). Finally, the midterms will trigger a major turnover in congressional committee chairs; legislators who are relatively unknown to Australia will take the chairman’s gavel on key committees covering foreign relations, trade and defence.

A preview of the midterms

Midterm election results are difficult to forecast due to unpredictability over voter preferences and, more importantly, voter turnout. Barely 40 per cent of eligible American voters have cast a ballot in recent midterm elections, well below the presidential election average of around 60 per cent.5 Traditionally, the Democratic Party’s base of young and non-white Americans are significantly less likely to vote than their older, whiter Republican counterparts.6 Republicans, for instance, were more than 20 per cent more likely to vote than Democrats in 2010 and 2014.7 Yet, a strong Democratic turnout in recent special elections suggests a reversal of this trend in 2018.8 Much depends on whether Trump’s base will vote without the president on the ballot, and the degree to which Democrats can convert the noise and enthusiasm on the left into numbers at polling booths in November.

House

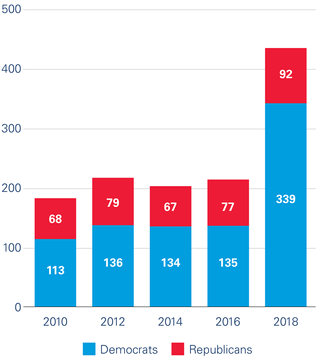

History and a string of Republican retirements favour Democrats to achieve the net gain of 24 seats necessary to retake the House in 2018. The president’s party typically loses an average of 26 House seats in post-World War Two midterms.9 This number has been considerably higher when the president’s approval rating sits below 50 per cent, as it has throughout Trump’s 14-months in office.10 Moreover, while both parties face a similar number of departures by House incumbents who are vacating their seats to run for higher office, only eight House Democrats are retiring outright compared to 24 Republicans.11 Democrats are favoured to pick up several of the seats held by retiring Republicans, many of whom are moderates who would have faced a difficult race for re-election.12

Democrats are also performing strongly in fundraising and candidate recruitment, indicating successful cultivation of the grassroots campaigners and donors who play a vital role in US elections.13 The Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee (DCCC) – the official campaign arm of House Democrats – outraised its Republican equivalent for eight consecutive months from May to December 2017.14 Far more Democrats, including a record number of women, have filed to run for office than in previous campaign cycles.15 The strength of well-resourced Democratic candidates in 2018 has made it possible for the party’s high command to target 101 Republican-held seats.16

Nonetheless, Democrats will have to perform very strongly to win the popular vote by the margin required to retake the House. The Democrats’ highly concentrated pockets of support and the national skew of gerrymandered districts give the Republican Party an advantage. For example, in the 2016 House of Representatives elections – concurrent to the presidential election – Republicans achieved 49.1 per cent of the popular vote, which translated to 55.4 per cent of House seats, whereas Democrats’ 48 per cent of the popular vote earned them just 44.6 per cent of House seats.17 According to FiveThirtyEight pollster Nate Silver, Democrats will have to win the popular vote by roughly seven points to have a competitive chance at retaking the House.18 This is shaping up to be a close call: for the last six months, Democrats have led party-preferred polling by a minimum of five points and often closer to ten points.19

Democrats’ disadvantage in the House

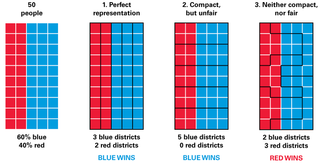

The total number of House districts apportioned to each state is derived from US Census figures and updated every ten years. In the majority of US states, these district boundaries are drawn by state legislatures, rather than by an independent electoral commission as in Australia.20 The party with a majority in a state legislature often uses control of electoral redistricting to create districts that confer a partisan advantage for their party’s candidates.

Partisan gerrymandering involves packing the opposing party’s voters into a few concentrated districts, diminishing the opposition party’s seat share relative to its state-wide share of the vote. While one party may win some districts in a landslide, they will be less competitive in districts overall (see graphic). In extreme cases this results in a large discrepancy between vote share and seat share. For example, in the 2012 North Carolina elections for the House, Democrats received 50.5 per cent of the popular vote state-wide, yet secured only four of the state’s 13 seats.21

Partisan gerrymandering involves packing the opposing party’s voters into a few concentrated districts, diminishing the opposition party’s seat share relative to its state-wide share of the vote.

This practice is not limited to the Republican Party. But the last round of redistricting took place in 2011, when Republicans controlled a majority of state legislatures.22 Of the 340 House districts not determined by an independent redistricting commission, Democrats drew less than 50.23 In recent congressional elections, Republicans have tended to win outsized shares of seats in the House relative to their share of the popular vote.

Partisan gerrymandering is only partly to blame for Democrats’ underrepresentation in the House. The party also faces a perennial disadvantage from electoral geography: Democrat voters are overwhelmingly clustered in urban areas and college towns. These concentrated majorities make it difficult for support to be spread across multiple districts and it easier for Republican controlled legislatures to engage in pro-Republican gerrymandering.

Gerrymandering, explained: Three different ways to divide 50 people into five districts

Senate

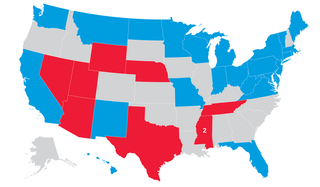

Despite the Republican Party’s razor thin majority in the upper chamber – 51 seats to 49 – the GOP is expected to retain the Senate. US Senators serve six-year terms, with one-third of the Senate elected every two years. Democrats up for re-election this year hold seats they won in 2012,24 in an election cycle that comfortably re-elected Barack Obama and elected several Democratic senators in either competitive or traditionally Republican states.25 The November midterms will be an uphill battle: Democrats will need to spread their resources to defend 26 Senate seats whereas Republicans are only defending nine.

This highly uneven Senate map favours Republicans, who stand to lose few seats but have an opportunity to gain many of the seats held by Democrats.26 If Republicans successfully hold all nine seats, or lose only one, they will retain the Senate majority.27 Most Republican Senators on the ballot this year are highly favoured to win re-election – only Nevada’s Dean Heller is defending a state won by Hillary Clinton in 2016.28

By contrast, ten of the 26 Senate seats that the Democrats are defending this year were won by Donald Trump in 2016.29 The Republican Senate campaign is targeting these vulnerable Democrats, whose approval ratings are falling amidst well-resourced media campaigns from their Republican challengers, the National Republican Senatorial Committee, and other conservative groups.30 The most vulnerable Democratic senators include Joe Manchin III in West Virginia (Trump carried the state in 2016 by +41.7 points) and Heidi Heitkamp in North Dakota (Trump +35.7 points).31 But neither seat is a shoe-in for Republicans due to these senators’ local brand and moderate voting record.

2018 Senate map

The quality of Republican Senate candidates will be critical to the GOP’s prospects of widening its slim majority. In recent midterm elections, the Republican base has nominated several controversial candidates in the primaries who then lost competitive general elections.32 The mistake was arguably repeated in Alabama’s special election last year, when Roy Moore won the primary against the establishment-backed Luther Strange, but subsequently lost the seat to Democrat Doug Jones in one of the most consistently Republican states in America.33 Upcoming competitive primaries – to be held from May to September – will be an important indicator of the trajectory of the Republican Party and determinant of its prospects in the November election.

Impact on US politics

If the Democratic Party takes either chamber, its political strategy after the midterms will have considerable influence on America’s political climate in the lead-up to the 2020 presidential election. Some centrist Democrats will want to find common ground with President Trump, potentially on infrastructure.34 Since President Trump’s election, many vulnerable, centrist Democratic senators have been prepared to curb their criticism of the president and vote for some of his priorities, due to their more conservative constituencies and desire not to invoke unbridled opposition from the Trump White House in their re-election bid.35 Indeed, President Trump’s unpredictable approach on many issues – such as his debt ceiling deal with Democrats in September 2017 – may offer some opportunities for bipartisan co-operation in 2019 and 2020.36

If Democrats retake the House of Representatives they will face considerable pressure from their base to immediately vote to impeach President Trump

But left-wing Democrats and much of the party’s liberal base demand full-throated resistance to President Trump. If Democrats retake the House of Representatives they will face considerable pressure from their base to immediately vote to impeach President Trump.37 Additionally, Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation is likely to continue into 2019 – once released, his report will add fuel to a highly-charged political climate.38 Impeachment in the House would be merely symbolic, because, after impeachment, a trial and guilty vote from a super-majority of two-thirds of the Senate is required. This is a very high threshold: in practice, all Democratic senators and, more importantly, almost 20 Republican senators would have to vote to convict and remove President Trump from office.39 Democrats might also create a special congressional committee with the express aim of damaging President Trump,40 in the mould of the Benghazi commission that was established by House Republicans in 2014 to smear Hillary Clinton in the lead-up to the 2016 election.41 Each of these scenarios would set a tone of hyper-partisan opposition to the president, create constant media distraction, and likely accentuate Trump’s erratic decision-making style.

More importantly for the US government’s ability to deliver on policy, a Democratic House of Representatives would have a platform to obstruct Republican legislation. The constellation of the House, Senate and White House between 2010 and 2014 provides a useful precedent: for the middle four years of Barack Obama’s presidency, Democrats had a majority in the Senate but the Republican House of Representatives successfully opposed a wide range of Democratic policy priorities and hamstrung the US government’s ability to function effectively.42 During this period of gridlock and polarisation, Congress enacted the highly damaging Budget Control Act and there was a 17-day government shutdown.43

Yet a ‘blue wave’ election that flips the House, followed by aggressive Democratic opposition to President Trump after the midterms, will not necessarily lead to the election of a Democratic president in 2020. For example, the Republican Party had major success in the 1994 and 2010 midterms, flipping control of one or both chambers of Congress in landslide results at the two-year mark of Bill Clinton and Barack Obama’s presidencies.44 But Clinton effectively reoriented his administration’s agenda and the US economy recovered under Obama, ensuring that both Democratic presidents were easily re-elected.

Neither party has a realistic chance of emerging with the filibuster-proof 60-vote majority required to prevent the Senate minority party from obstructing a range of legislation.

Whichever party emerges from the midterms with a Senate majority, the exact numbers in the upper chamber are critical. Neither party has a realistic chance of emerging with the filibuster-proof 60-vote majority required to prevent the Senate minority party from obstructing a range of legislation.45 At present, Senate Leader Mitch McConnell holds a very slim majority, leaving the Republican agenda vulnerable to defections by members of his caucus who have resisted party leadership on the grounds of personal conviction or state-specific concerns. Three defections prevented Republicans from repealing and replacing Obamacare.46 There will presumably be a new push to undo Obamacare after the midterms if Republicans hold the House and expand their majority in the Senate. A related complication is the health of the Republican Senate caucus that boasts half a dozen octogenarians.47 Health-induced absences in the Republican caucus deprive McConnell of important votes.48 If Republicans keep the Senate, but with a narrow majority, McConnell will continue to be plagued by the ‘difficult’ members of his caucus such as firebrand Rand Paul and moderate Susan Collins.

In the unlikely event that Democrats perform strongly enough to flip the Senate in November they would probably also win the House, enabling full-scale obstruction. A Democratic Senate may slow or prevent the confirmation of some of President Trump’s nominees to the Executive Branch – including the State Department, Defense, and ambassadorial posts – and potentially the Supreme Court.49 With his legislative agenda paralysed, Trump would presumably turn his focus to rule by executive orders and concentrate on foreign policy, as President Obama did in 2015 and 2016 when the Republicans controlled both houses.

The primaries and polarisation

The primaries and November midterms will be an important marker of the trajectory of both the Republican and Democratic parties. Since President Trump won the 2016 election, few congressional Republicans have been prepared to publicly champion multilateral free trade agreements or discuss the benefits of immigration, and the party is less willing to discuss entitlement reform.50 Whereas Republicans were vocal in their criticism of the ballooning government deficits and national debt under Obama, the Republican majority in the 115th Congress has voted for multiple bills that would push up the US national debt by more than a trillion dollars.51

The iron laws of arithmetic have played a key role in the party’s reorientation on policy: President Trump is much more popular with the average Republican voter than Mitch McConnell or Paul Ryan, who have Reagan-inspired ‘establishment’ policy biases, hence the party’s shift on trade, immigration and entitlements.52 The primaries will pit many incumbent establishment Republicans backed by Ryan and McConnell against candidates more closely aligned to Trump and populist forces. If these challengers are successful, they will accelerate the speed of the Republican Party’s ideological move away from Reagan, towards Trump.

The primaries will pit many incumbent establishment Republicans backed by Ryan and McConnell against candidates more closely aligned to Trump and populist forces.

Meanwhile, the Democrats are moving to the left, adopting many of the progressive priorities that helped Bernie Sanders win 43 per cent of votes in the 2016 primary against Clinton.53 For instance, many presumptive 2020 Democratic presidential candidates in the Senate – such as Elizabeth Warren, Kirsten Gillibrand, Kamala Harris and Cory Booker – have adopted the Sanders single-payer Medicare-For-All plan that was to the left of Obama-era orthodoxy.54 Some progressive Democrats will launch primary challenges against incumbents in the coming months who, if elected to Congress, will continue to pull the party leftwards on other issues including the minimum wage, reproductive rights and the national debt.55 Meanwhile, if 2018 produces a ‘blue wave’, a new cohort of Democrats will come to Congress in January 2019 powered by the hard-line, anti-Trump views of their liberal base and motivated to derail Trump’s legislative agenda and presidency.

In sum, America’s two major parties are moving further apart and are likely to continue to split throughout the midterms. House leaders Paul Ryan and Nancy Pelosi already face a difficult task reaching bipartisan compromise or even controlling their own caucus. As recent special elections in Alabama and Pennsylvania have illustrated, Republican and Democratic candidates are willing to run not just against the opposing candidate, but also against their own party leadership. Campaign season will exacerbate hyper-partisanship. President Trump will seek to mobilise his base through rallies and a focus on ‘cultural flashpoints’, such as arming teachers and criticising Americans who do not stand for the national anthem.56 As Democrats lack a national leader – Nancy Pelosi is unpopular, Senate leader Chuck Schumer is new to the role, and Barack Obama has largely remained outside day-to-day political combat – their campaign will centre on opposition to Trump, accentuating partisan differences.57

Implications for Australia

Deeper partisanship and polarisation after the midterms will make bipartisan compromise and stable governance harder to achieve. There has already been one government shutdown during this Republican-majority Congress, due to divisions within both parties and an absence of compromise between them. There may well be more shutdowns after the midterms if Democrats hold one or both chambers because a greater degree of bipartisanship would be required. In light of deepening polarisation, the US federal budget – and in particular the defence budget – will continue to be appropriated after a delay of months. Congress has not passed a defence budget on time since 2009, under presidents and congresses of varying partisan compositions. Consequently, the US military has been operating on a series of Continuing Resolutions that give senior leaders no certainty over funding, leaving them hamstrung in their ability to make long-term strategic decisions.58

There may well be more shutdowns after the midterms if Democrats hold one or both chambers because a greater degree of bipartisanship would be required.

Second, there is little indication that Congress has the political will to pass a multilateral trade agreement in the near future. For example, the successful vote in the House for Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) in June 2015 – which in effect served as a proxy vote for the TPP – passed by the narrow margin of 218-208. Only 28 of 186 House Democrats voted in favour of TPA, despite the fact that it was championed by then-President Obama.59 Almost three-quarters of Republican legislators voted in favour, but since then President Trump’s strident opposition to the TPP and other multilateral trade deals have led to a distinct cooling in Republican members’ views on trade. The recent letter by 25 Republican Senators urging President Trump to rejoin the TPP is an exception to this trend,60 but the Senate has historically been more pro-trade than the House, and trade agreements need to be approved by both chambers. For the United States to re-enter the TPP or sign new trade agreements, support from President Trump, a majority of Republicans and a significant number of Democrats would be required. Each seems unlikely, and would become even less plausible in the likely event that the midterms elect legislators sceptical towards free trade (left-wing Democrats and Trump-aligned Republicans). If Democrats take the House, there is little-to-no chance the United States would rejoin the TPP after the midterms.

Finally, the midterms will result in a major turnover in congressional committee chairmanships. Should Democrats retake the House, they will take the chairman’s gavel in every committee. In most cases, the current Democratic ranking member is in line to take over the committee, such as representatives Adam Smith on Armed Services and Eliot Engel on Foreign Affairs. If Democrats take the House and Republicans hold the Senate, co-ordination between correlating committees will become more difficult. Even if Republicans retain control of the House there will be a wide array of new committee chairs after the midterms due to the retirement of nine of the 25 House Republican committee chairmen, including Foreign Affairs Chair Ed Royce.61 The Senate personnel changes will be perhaps more important. Senate Foreign Relations Chairman Bob Corker and Finance Committee Chairman Orrin Hatch are both retiring, and the health of Armed Services Chairman John McCain is in question. They are likely to be replaced by figures who are relatively unknown to Australia, respectively: Jim Risch, either Chuck Grassley or Mike Crapo, and Jim Inhofe.62 To prepare for this future, senior Australian politicians visiting Washington should seek meetings with these representatives and senators poised to assume leadership roles on key policy issues from January 2019.