Foreword

Even as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine sees the United States confronted with a new set of protracted challenges in Europe, the Indo-Pacific remains the primary theatre for strategic competition. A seismic shift in the balance of power driven by China’s sustained military modernisation and rising assertiveness poses a major challenge to the United States, Australia, and their Indo-Pacific allies and partners.

China continues to wield its growing power in unprecedented ways, undermining the foundations of the regional order through a multi-dimensional, whole-of-government strategy. Beijing is leveraging an increasingly sophisticated toolset in the grey zone between peace and war, including non-military means, economic coercion, and political interference, to pursue incremental changes to the status quo. At the same time, China’s formidable military capabilities, its ongoing nuclear build-up, and its emerging advantages in new domains like cyber and space raise hard questions about the United States’ ability to deter or prevail in a regional conflict.

In this context, it has never been more essential for the United States and Australia to adapt and strengthen their approaches to regional deterrence and defence – individually, together, and with like-minded partners. But for a strategy of collective deterrence to succeed, Canberra and Washington will need to pursue deeper alliance integration in ways that are multi-domain in scope, coordinated at the interagency level, and in lockstep with the shared interests and objectives of other regional players. This work enjoys widespread support in Washington and Canberra, reflected in the ambitious agenda of recent Australia-United States Ministerial Consultations (AUSMIN) and in the creation of the Australia-United Kingdom-United States (AUKUS) trilateral defence industrial pact.

Advancing an integrated and collective strategy to deter Chinese aggression is no simple task. Canberra and Washington broadly agree on the nature of the threat Beijing poses and share overlapping strategic objectives. Yet, differences in capabilities, interests, policy priorities, and threat perceptions mean the two allies do not always see eye-to-eye on the ways and means of deterrence, the priority given to specific actions, or the risks of taking them. Reconciling these differences is crucial if the United States, Australia, and their allies and partners are to regain the initiative in the face of China’s efforts to reshape the Indo-Pacific order.

To strengthen dialogue and policy debate about growing requirements of deterrence within the alliance, the United States Studies Centre (USSC) and Pacific Forum hosted the third Annual Track 1.5 US-Australia Indo-Pacific Deterrence Dialogue virtually in March 2022, bringing together over 30 US and Australian experts from a range of government and research organisations. This year’s theme was “A new age for deterrence and the Australia-US alliance,” with a focus on exploring the next steps for the alliance’s deterrence agenda, including new and emerging avenues for integration.

Both institutions would like to thank the Australian Department of Defence Strategic Policy Grants Program and US grant-making foundations for their generous support of this engagement.

The following summary reflects the authors’ account of the dialogue’s proceedings. It does not necessarily represent their views or the views of their home organisations. It solely seeks to capture the key themes, perspectives, and debates from the discussions; and does not purport to offer a comprehensive record. Nothing in the following pages represents the views of the Australian Department of Defence or any of the other officials or organisations that took part in the dialogue.

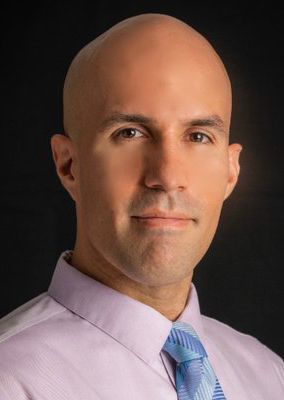

Ashley Townshend, Co-Chair, US-Australia Indo-Pacific Deterrence Dialogue, Non-Resident Senior Fellow at the United States Studies Centre

David Santoro, Co-Chair, US-Australia Indo-Pacific Deterrence Dialogue, President and CEO at the Pacific Forum

Executive summary

1. Australia and the United States are more firmly aligned than ever before on the need to advance a collective approach to deterrence and defence in the Indo-Pacific. This consensus has consolidated quickly over the past five years owing to China’s intensifying efforts to challenge the prevailing balance of power and a growing recognition in both Canberra and Washington that the United States can no longer defend the regional order by itself. While there is broad agreement that Australia, the United States, and Japan should form the backbone of collective efforts to deter high-end war-fighting threats, views diverge over what this looks like in practice and how much emphasis should be placed on bringing other regional countries into nascent collective defence arrangements or contingency-specific groupings.

2. Canberra and Washington have different views on the extent to which armed forces should prioritise shaping the regional strategic environment and preparing for high-end military contingencies. Most Americans hold that the Department of Defense should not play a major shaping role and should instead focus on setting the theatre, strengthening deterrence, and preparing for military challenges. For Australia, by contrast, defence engagements play a central role in efforts to shape regional alignment preferences and secure access and influence in key countries. While these priorities are not mutually exclusive, they point to differences in how each ally thinks about its regional military posture: whereas Washington plans “backwards” from projected war-fighting requirements, Canberra tends to plan “forward” in support of shaping objectives.

3. The role of expanded US-Australia force posture initiatives looms large in alliance debates about shaping the strategic environment. Canberra and Washington both regard the new suite of force posture initiatives as serving an important assurance function. By acclimatising regional countries to an increasingly regular tempo of bilateral and multilateral military exercises and operations centred around these arrangements, the alliance can shape perceptions about its collective commitment to regional security. From Canberra’s standpoint, leveraging Australia’s strategic geography to support a robust US forward military presence is a key contribution to both deterrence and shaping.

4. The United States’ concept of “integrated deterrence” is widely regarded as a useful framework for addressing the multi-dimensional strategic challenges China presents the region. But there are concerns that it does not clearly identify the types of activities that Washington seeks to deter, or precisely define the role for military force in this framework and its relationship with non-military means. Many believe that America’s failure to deter Russia’s invasion of Ukraine highlights the fact that credible military threats remain essential. There are concerns that overreliance on non-military tools in the Indo-Pacific could weaken deterrence and lead Washington and its allies to be self-deterred, particularly where there are asymmetries of interest between the United States and China.

5. There is broad agreement that efforts to resource a strategy of conventional deterrence by denial need to proceed with far greater urgency. For the United States, this requires larger investments in distributed forward basing, precision strike networks, fuel and munitions stockpiles, and integrated air and missile defences. Australia has a growing role to play in supporting this agenda though bilateral force posture initiatives. While the growing defence budgets and more proactive defence strategies coming out of Canberra and Tokyo are a welcome sign of investment in collective defence, the extent to which Australia and Japan are able and willing to tailor their defence forces to collective force structure requirements is less clear.

6. There is widespread support for deepening cooperative strategic planning initiatives between Australia and the United States on Indo-Pacific security flashpoints. These should focus on establishing shared thresholds for political risk and collective action ahead of a crisis, and on delineating alliance roles and responsibilities. Yet, there is less agreement on which scenarios should be the focus of cooperative planning efforts. Washington has identified Taiwan as the most likely flashpoint for high-intensity conflict in the region. Although Canberra shares US concerns over Taiwan, it is keen to focus collective planning efforts on a wider range of prospective contingencies in Southeast Asia and the Pacific, many of which lie at the intersection of Chinese grey zone coercion and conventional military activity.

7. Risk perceptions in Canberra and Washington will rarely align perfectly in crisis scenarios, not least because Australia, as a middle power, is more vulnerable to Chinese coercion. This reinforces the need for alliance processes to identify and reconcile political and military risk calculations ahead of a crisis. The operational significance of this endeavour must not be overlooked: Failure to develop a shared understanding of the costs and risks associated with combined military capabilities or force posture initiatives could have significant implications for the allies’ ability to employ these assets before a crisis, as a means of crisis management, or during a conflict.

8. There is uncertainty over the degree to which Southeast Asian nations share US and Australian assessments about the regional order. By and large, Americans tend to be more supportive of the argument that Southeast Asian nations are resigned to the local hard-power realities of US-China competition and, in many cases, are quietly supportive of initiatives designed to shore-up a favourable balance of power. Australians are more cautious. Rather than waiting for regional partners to catch-up to or adopt allied balancing preferences, Canberra seeks to adjust regional security architecture at a pace that these states can cope with and in a way that provides them with strategic benefits, irrespective of their willingness to align.

9. Washington and its Indo-Pacific allies can no longer think of nuclear weapons as separate from other instruments of war. Just as China has integrated its expanding nuclear arsenal with other elements of national power into its overall theory of victory, so too must the United States and its allies. Doing so will not lower the threshold for nuclear use but recognise the reality that any segregation of nuclear weapons is now artificial. As America’s Indo-Pacific allies do not have nuclear weapons, the logic behind greater integration is that they be read into US nuclear planning and operations at a much earlier stage ahead of a crisis, a proposition which seems attractive to Canberra.

10. Australia and the United States see expanded defence industrial cooperation as essential to enhancing the credibility of collective deterrence in the region. This should include deepening industrial base integration, reforming export controls, updating technology sharing and transfer arrangements, and accelerating processes for capability co-development. Yet, there are formidable obstacles to this agenda. These are primarily cultural in nature, though they manifest in a wide range of longstanding legal, regulatory, institutional, and bureaucratic barriers within the US system. Without sustained and disciplined leadership from the White House, Congress, and State Department, progress on defence industrial integration will be incremental at best.

Shaping the strategic environment

Regarding the role that defence departments and the armed forces should play in shaping the regional strategic environment, Australia and the United States have somewhat diverging views. By and large, American practitioners see it as risky and inappropriate for the US Department of Defense to assume anything more than a minor role in advancing a shaping agenda.

- In working to counter China’s grey zone tactics, Australia and the United States have embraced whole-of-nation efforts to shape the Indo-Pacific strategic environment in ways that promote stability, rules, and resilience to coercion. This has involved a shift away from “siloed” approaches to regional security and a bureaucratic push to integrate all elements of national power into a more pro-active statecraft. Inside government, this has manifested in efforts to fuse interagency tools – such as defence cooperation, development assistance, infrastructure financing, strategic communications, and intelligence authorities – to craft more effective domestic and regional resilience-building strategies. Efforts to mobilise non-government actors, while difficult in democracies, are also underway, particularly in the telecommunications, media, and cultural sectors.

- The deterrent value of shaping activities is one of denial and resiliency. By making China’s grey zone tactics – such as disinformation, economic pressure, malicious cyber activity, and covert interference etc. – more costly and difficult in the face of robust institutions, rules, and civil society practices, Canberra and Washington hope to convince Beijing that coercion will not achieve its strategic objectives. Shaping activities are also intended to thicken the network of relationships among like-interested partners across the region and thereby deliver a collective assurance effect. Crucially, by supporting regional countries’ efforts to bolster their own sovereign autonomy and resilience, Australians and Americans hope that shaping activities will positively influence alignment dynamics and help set the political conditions for future military access in the region.

- Regarding the role that defence departments and the armed forces should play in shaping the regional strategic environment, Australia and the United States have somewhat diverging views. By and large, American practitioners see it as risky and inappropriate for the US Department of Defense to assume anything more than a minor role in advancing a shaping agenda. They worry that shaping activities will take focus and resources away from the Pentagon’s core warfighting role, undercutting its preparations for future high-end conflict and increasing the risk that conventional deterrence could fail. Proponents of this view argue that shaping activities should be the responsibility of the State Department and other agencies, leaving the Pentagon to focus defence cooperation on military objectives.

- By contrast, most Australian practitioners see a key role for the armed forces in shaping the strategic environment beyond the narrow requirements of military deterrence. They argue that defence-focused discussions about setting the theatre for high-end contingencies do not resonate with the priorities of Southeast Asian and Pacific Island states; whereas defence cooperation initiatives that are designed to deepen relationships and build resilience can serve to position Canberra and Washington as security partners of choice. Both are needed in equal measure. From Australia’s standpoint, there is value in using defence-led shaping activities to bolster regional alignments, develop peacetime access arrangements, and counter day-to-day grey zone activities, even if the regional partners at the heart of these efforts are unlikely to directly support allied warfighting efforts or contribute to high-end conflict scenarios.

- The role of expanded US-Australia force posture initiatives looms large in alliance debates about shaping the strategic environment. Canberra and Washington both regard the new suite of force posture initiatives unveiled at AUSMIN 2021 as serving an important assurance function. Specifically, by acclimatising regional countries to an increasingly regular tempo of bilateral and multilateral military exercises and operations centred around these arrangements, the alliance can shape perceptions about its collective commitment to regional security. From Canberra’s standpoint, leveraging Australia’s strategic geography in this way is a key contribution to both deterrence and shaping.

- Yet, Canberra and Washington also tend to approach force posture initiatives from opposing directions. This is a function of their differently weighted priorities when it comes to the shaping and warfighting aims of defence cooperation. Whereas the United States approaches its force posture planning “backwards” to meet the needs of high-end warfighting scenarios, Australia generally plans its posture “forwards” as a way of facilitating the Australian Defence Force’s (ADF) role in shaping the regional strategic environment as well as advancing operational goals. In this way, while Canberra regards force posture initiatives as a critical component of both shaping and deterrence agendas, it is far from clear that Washington sees them in the same way. This expectation gap must be closed in future alliance consultations.

- The relationship between shaping activities and conventional military deterrence remains disputed at the higher end of the conflict spectrum. On the one hand, the Biden administration’s use of intelligence declassification to undermine and pre-empt Russia’s grey zone activities, narratives, and planning before and during its invasion of Ukraine demonstrated the considerable benefits of shaping activities in constraining and even foreclosing adversaries’ options short of conventional warfare. For Australia and the United States, there is ample reason to consider similar approaches with key partners in Southeast Asia and the Pacific to reveal and disrupt Chinese coercion. However, the failure of US efforts to ultimately deter Russian aggression raises questions about the effectiveness of relying on asymmetric tactics in isolation from conventional military power. In the Indo-Pacific, it is necessary to explore the extent to which conventional forces could underwrite more effective shaping or counter-grey-zone strategies; and whether this more integrated approach – through failure or success – might push China to resort to kinetic means to achieve its aims.

- Australians and Americans are alert to the fact that democracies are disadvantaged in prosecuting multi-faceted shaping strategies owing to checks and balances on government power and the inability of the state to directly coordinate non-government actors and tools. By contrast, China’s relative freedom of action to execute whole-of-nation grey zone activities allows it to generate geopolitical momentum through the slow but steady advancement of its revisionist goals.

Developing integrated deterrence

Looking ahead, the challenge will be to refrain from making integrated deterrence a strategy about everything and to define the precise behaviours, actions, or activities that need to be deterred. The process of narrowing the focus to deterring aggression in specific scenarios, with specific ways and means, has begun; and, in the wake of the war in Ukraine, is accelerating.

- The United States’ Indo-Pacific Strategy calls integrated deterrence the “cornerstone” of America’s approach to bolstering regional security. It adds that Washington “will more tightly integrate [its] efforts across warfighting domains and the spectrum of conflict to ensure that the United States, alongside our allies and partners, can dissuade or defeat aggression in any form or domain.” Broadly speaking, integrated deterrence seeks to provide a more comprehensive, or more holistic, framework for dissuading adversaries across the conflict spectrum than traditional approaches to deterrence. It aims to “tighten the net” across military domains and leverage all elements of national power, including in economics, trade, and investment, for deterrence effect. It is, in other words, a whole-of-nation approach to deterrence. It relies on strong coordination and cooperation across and between multiple government agencies and private entities, as well as among US allies and partners, such as Australia.

- Integrated deterrence is a multi-dimensional response to a multi-dimensional problem. Competitors such as China and Russia have developed strategies to contest and upend the established orders in the Indo-Pacific and Europe. Chinese and Russian strategies have involved the patient and methodical integration of the whole-of-nation ways and means to push back against these orders. This has taken place primarily at the grey zone level and, especially in China’s case, in non-military areas. Of late, pushback has taken more of a conventional and even nuclear character, as exemplified by developments in the ongoing war in Ukraine. China, too, has implemented sophisticated grey zone strategies backed up by increasingly frequent conventional shows of force that target Taiwan specifically. Better integration of deterrence equities by the United States and its allies and partners is needed as a response to these problems.

- Integrated deterrence is not an entirely novel concept. It is anchored in the fundamental and longstanding principles of deterrence, which include, deterrence by denial, deterrence by resilience, and deterrence by punishment. The combination of different instruments to generate deterrence is not new either; nor is the push to encourage greater interoperability with US allies to maximize deterrence effectiveness.

- But integrated deterrence does include new features. It is, at root, cross-domain in character, promoting not tighter integration between conventional and nuclear assets but a continuum between the conventional and nuclear domains, as well as enhanced resilience in, and better use of, the space and cyber domains. Integrated deterrence is meant to operate across the spectrum of conflict, from grey zone challenges to high-end contingencies. Finally, it is intended to work across geographic theatres and US combatant commands owing to the fact that China, and to a lesser extent, Russia, are not only active in an isolated geographical area, but have a global reach.

- Advancing a strategy of integrated deterrence is not without challenges. Connecting multiple warfighting domains that have traditionally been siloed is difficult, even more so when it comes to non-military tools. In the United States, the Department of Defense is often looked to as the lead for advancing this approach owing to its familiarity with strategies of deterrence and coercion. But queasiness often arises when the Pentagon seeks interagency assistance in its deterrence messaging. There is frequent pushback and a “don’t-tell-us-what-to-do” reaction. Another difficulty is operating across the spectrum of conflict and with non-military tools where the Pentagon is not well positioned to take the lead (as discussed above). Although the United States has rich experience in deterring high-end contingencies, it has proven less adept in deterring grey zone challenges. Determining the right policy leads and settings for integrated deterrence will be critical. In some cases, success will also hinge on leveraging the knowledge and experience of US allies.

- Looking ahead, the challenge will be to refrain from making integrated deterrence a strategy about everything and to define the precise behaviours, actions, or activities that need to be deterred. The process of narrowing the focus to deterring aggression in specific scenarios, with specific ways and means, has begun; and, in the wake of the war in Ukraine, is accelerating. There is growing integration across and between departments and allies over risk and threat assessments, military interoperability, and posture and planning decisions. In the Indo-Pacific, agreement on multilateral constructs, such as the Quad, or on the deepening relations with third parties, stand as foundations upon which integrated deterrence can develop. A considerable amount of work remains to explore how to best deter aggression against Taiwan using integrated means.

- Numerous questions remain. One is about extended deterrence. Some allies fear that integrated deterrence may spell the end of extended deterrence because a tighter security relationship with the United States could eliminate the US need to extend its nuclear forces to defend allies. The counterargument, however, is that greater integration between the United States and its allies increases the odds of a US intervention in the event of a conflict. (US officials also often stress that the nuclear dimension is distinct and separate from integrated deterrence.)

- Another question is whether integrated deterrence is meant to be a complement or a substitute to traditional, conventional deterrence. While the former would be an improvement, the latter would be problematic because it would dilute deterrence efforts. A related charge is effectiveness. Many wonder whether integrated deterrence can deliver. Some explain that the international campaign against Russia has failed to force Moscow to give up on its invasion of Ukraine. They add that mounting a similar campaign against China in the event of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan would likely be even less successful because many more countries are dependent on the Chinese economy than they are on the Russian economy. If that is the case, then why even focus on integrated deterrence instead of doubling down on traditional deterrence? According to this argument, the United States, Australia, and their allies and partners would do better to focus on improving their military capabilities – traditional, advanced and asymmetric – and developing new doctrine to strengthen their collective ability to deter and defeat Chinese aggression. Military deterrence, however, is not a silver bullet either and is limited by the strength of specific interests at stake. Rather than viewing integrated deterrence as a substitute for traditional deterrence, the two must work hand in hand.

Strengthening conventional deterrence by denial

While there is broad agreement that Australia, the United States, and Japan should form the backbone of collective efforts to deter high-end military threats – including by contributing to strategic objectives beyond the direct defence of Japanese and Australian territory – there is not yet a consensus over what this looks like operationally.

- A strategy of forward-based collective deterrence by denial is widely regarded by alliance practitioners as the best way to dissuade Chinese aggression in the Indo-Pacific in a cost-effective and timely manner. As laid out in the 2018 US National Defense Strategy, this strategy seeks to deter Beijing from attempting to forcefully revise the status quo by denying it the speed, surprise and conventional military superiority required to achieve a quick and easy fait accompli. Biden administration officials have stressed deterrence by denial remains a cornerstone of the 2022 National Defense Strategy. This approach enjoys active support from Australia, Japan and other capable allies and partners in the region.

- There is also widespread agreement that efforts to resource a strategy of denial need to move with far greater urgency. For the United States, this requires a suite of investments in distributed forward basing, precision strike networks, increased fuel and munitions stockpiles, and integrated air and missile defences. Despite incremental progress on these priorities through the Pacific Deterrence Initiative, there are growing concerns in US defence circles and allied capitals, including in Canberra, that the Pentagon is not on a trajectory to bolster its regional warfighting posture in a timeframe that is relevant to deterring Chinese aggression against Taiwan, which many expect could materialise this decade. Washington, for its part, sees the larger defence budgets and more proactive defence strategies coming out of Canberra and Tokyo as welcome signs of allied investment in a collective denial strategy. Ensuring that these investments complement existing and future US force structure and operational requirements is a critical objective for American thinkers, many of whom would like this issue feature in combined strategic planning initiatives within and between alliances going forward. The extent to which Australia or Japan are able and willing to tailor their defence forces to meet collective force structure requirements is less clear.

- Australia and the United States are more firmly aligned than ever before on the need for a collective approach to deny Chinese aggression in the Indo-Pacific. This consensus has consolidated dramatically over the past five years owing to China’s intensifying efforts to challenge the prevailing balance of power and a growing recognition in both Canberra and Washington that the United States can no longer defend the regional order by itself. While there is broad agreement that Australia, the United States, and Japan should form the backbone of collective efforts to deter high-end military threats – including by contributing to strategic objectives beyond the direct defence of Japanese and Australian territory – there is not yet a consensus over what this looks like operationally.

- At the same time, there are concerns in some US strategic circles over the true extent of Australian and Japanese commitments and their durability in the face of escalation, particularly in the context of a Taiwan contingency. While all agree on the need to clarify and test these mutual expectations, American practitioners tend to be sceptical as to whether any meaningful consensus can be reached before a crisis is in motion. Some take the unexpectedly robust Western response to the conflict in Ukraine as evidence that alignment dynamics will only become clear on the brink or during a crisis. Many, however, argue that the Ukraine experience should serve as a wake-up call and trigger immediate efforts to ensure tight alignment and coordinated military planning between the United States, Australia and Japan in the event of a contingency. Most Australians insist on the need to establish clear political and military risk thresholds to govern alliance action on a range of scenarios well ahead of time.

- There is no consensus among Americans on the extent to which reforms within the Department of Defense are required to prepare the United States to address Indo-Pacific deterrence challenges in sync with Australia, Japan, and other key allies and partners. Many defend the Pentagon’s record of building a capable military force – often in spite of bureaucratic and programmatic inefficiencies – as evidence that Washington is doing well enough. Others, however, argue that the pace of change inside the Pentagon – and the US Government more broadly – is not sufficient to prepare the Joint Force to integrate seamlessly with allies as part of a strategy of collective deterrence. Ongoing obstacles to information sharing, combined military planning, technical interoperability, export control reform, and defence technology transfer, to name a few key examples, are of significant concern. Many Australians view the glacial progress on bilateral defence industrial cooperation as a bellwether for Washington’s willingness to accept the risks inherent in advancing a more integrated alliance.

Strategic dynamics and extended nuclear deterrence

China could become more assertive and even more aggressive at the conventional and sub-conventional levels, especially in regional conflicts (and most notably over Taiwan), thinking that its nuclear arsenal gives it an ability to control and even prevent escalation. China could also rely more heavily on its strategic forces to put pressure on conventional conflicts and, by threatening outright escalation to the nuclear level, seek to terminate them in ways favourable to Chinese interests.

- China’s major nuclear build-up is one of the most dramatic strategic developments of the past year. Although officials have hinted at this build-up for several years, it was not until 2021 that satellite images appeared to publicly confirm that China was expanding its nuclear arsenal much faster and more widely than previously assumed. Significant uncertainty remains, however, because Beijing has rejected and even denied the evidence and continued to be deeply secretive about the size, shape, and composition of its arsenal and the endgame for its modernisation program. Still, several points are now clear. First, the Chinese nuclear arsenal is growing fast. Independent studies suggest that Beijing currently has approximately 300-350 warheads, with estimates of its future inventory ranging from 700 to 1,500 by 2035. Second, Chinese missiles, especially its intermediate- and medium-range missiles, are becoming increasingly accurate. Third, Beijing is now keeping part of its nuclear force in ready-to-launch mode during peacetime, a notable shift from its traditional practice of separating warheads and missiles. Finally, Beijing is buttressing its nuclear triad by expanding its land-based forces as well as investing heavily in nuclear submarines and new bombers. It has also tested new, “exotic” delivery systems, such as a fractional orbital bombardment system as well as hypersonic weapons.

- These developments have transformed China into a major nuclear-armed state. Beijing now has a sophisticated and highly diversified nuclear arsenal capable of conducting not only retaliatory strikes, but also, if necessary, of threatening first use. Yet, China has not abandoned all forms of nuclear restraint. Beijing continues to adhere, at least as a matter of policy, to no-first use. Moreover, it has been arming mostly short-range systems and has not opted for major force structure changes. Plainly, China could still do considerably more to embrace a combative nuclear policy and posture akin to Russia. But it has yet to make this choice. That said, Chinese nuclear developments are significant and, importantly, they have not taken place in isolation. Beijing has been engaged in a nuclear build-up and a major modernisation program of its advanced conventional forces, notably of its precision-strike and counter-space/cyber capabilities. It has developed, tested, and deployed many of capabilities, which, in recent years, have been maturing fast.

- Understanding the rationale behind these developments is critical to maintaining effective deterrence. At present, however, there is no clear-cut explanation, only speculation. Is Beijing merely trying to shore up weak retaliatory capabilities? Is it trying to go further and develop an arsenal as big and as sophisticated as the United States’ and Russia’s? Or has Beijing simply decided to “go big” without a strategy? Regardless, the net result of these developments is that they are entrenching the United States and China further into a situation of mutual vulnerability, at the nuclear level and increasingly across the board. As a result, following the logic of the “stability-instability paradox,” China could become more assertive and even more aggressive at the conventional and sub-conventional levels, especially in regional conflicts (and most notably over Taiwan), thinking that its nuclear arsenal gives it an ability to control and even prevent escalation. China could also rely more heavily on its strategic forces to put pressure on conventional conflicts and, by threatening outright escalation to the nuclear level, seek to terminate them in ways favourable to Chinese interests. In these instances, nuclear weapons would not be the main determinants of the use of force; this role would be filled by conventional capabilities. Nuclear weapons, however, would be the essential enablers of the use of force. Crucially, this means that a major conventional conflict with China is now probably more likely and that it would happen in the nuclear shadow.

- These developments require the United States and its allies to rethink and adapt their strategic policy and posture. The priority should be maintaining a favourable conventional balance of power because it is at that level that deterrence will likely succeed or fail. But Washington and its allies should not ignore the nuclear challenge. Not only do the United States and its allies now have to deter Chinese nuclear use, but they also have to deny Beijing’s reliance on nuclear weapons to support its conventional operations.

- At the most basic level, this means that the United States and its allies can no longer think of nuclear weapons as separate from other instruments of war. Just as China has integrated nuclear weapons with other elements of national power into its overall theory of victory, so too must the United States and its allies. Doing so will not lower the threshold for nuclear use but reflect the reality that any segregation of nuclear weapons is now artificial. Because it will increase US and allied flexibility vis-à-vis China, such integration is more important than proceeding with an American nuclear build-up in response, which some strategists in the United States are now proposing. Most, for now, reject a build-up, which they regard as unnecessary because the United States still dominates at the nuclear level and, for the foreseeable future, will continue to be capable of deterring both China and Russia, alongside other less capable nuclear powers.

- As America’s Indo-Pacific allies do not have nuclear weapons, the idea behind greater integration is that they be read into US nuclear planning and operations at much earlier stages in case a conflict arises, a proposition which, in the current regional security environment, seems increasingly attractive to Canberra. A side benefit of such a development will be reducing allied incentives to develop their own nuclear weapons, incentives which are currently increasing in Seoul and Tokyo. Aggregating conventional and nuclear assets, however, will pose difficulties for US extended nuclear deterrence. Because US extended nuclear deterrence in the Indo-Pacific has been premised on bilateral alliances and thus differed widely in its application, not every ally can be involved in US nuclear planning and operations in the same manner, or to the same extent. Looking ahead, tighter coordination and cooperation between and among the United States and its regional allies can help provide more uniformity.

- It is unrealistic to expect the United States and its Indo-Pacific allies to ever see completely eye-to-eye on how to deter or defeat China’s nuclear forces. Owing to proximity to China, regional allies, including Australia, are more concerned by Beijing’s theatre-range forces than its intercontinental missiles. The opposite is true for the United States. Similarly, while Americans see value in restricting US declaratory policy, allies are concerned by this possibility because they are on the frontlines in a rapidly deteriorating strategic environment and want the US to maintain its freedom of action to defend them. Reducing the daylight between and among Washington and its allies on these issues is within reach. Doing so, however, requires significant and sustained leadership focus and engagement across allied capitals.

Advancing collective defence within the alliance

There is no consensus among, or between, Australians and Americans on the degree to which Southeast Asian states share allied assessments of the regional order. Canberra and Washington appreciate the need to better address regional sensitivities surrounding new alliance initiatives, particularly in countries like Indonesia.

- While Australia and the United States agree on the importance of applying a framework of collective defence to Indo-Pacific contingencies, there are different views on which scenarios and issues should be the priority for cooperative strategic planning initiatives. Washington has identified Taiwan as the pacing challenge for high-intensity conflict in the region and, in this context, is especially focused on conventional-nuclear escalation dynamics. Canberra, too, is seized of the Taiwan challenge. But it is equally keen to focus collective planning efforts on a wider range of scenarios. These include deterrence challenges at the intersection of Chinese grey zone coercion and conventional military activity, and contingencies that could take place in Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands.

- There are several reasons for Australia’s interest in a wider strategic planning focus. First, most Australians do not regard a Taiwan crisis as unambiguously more important, or more likely, than other, more proximate, hybrid scenarios. Second, many Australians worry that the asymmetry in US and Australian interests in lower-intensity regional contingencies will complicate efforts to develop effective collective responses. Finally, Australians are concerned that prioritising one set of challenges over another creates a false dichotomy between high-end conflict and grey zone activity, rather than focusing attention on the linkages between these integrated challenges, often on the same escalation ladder.

- Australians and Americans have somewhat divergent views on the merits of pursuing multiple coalitions tailored to specific military challenges. To be sure, practitioners generally agree that Australia, Japan, and the United States are the most reliable parties when it comes to preparing for a high-end conflict over Taiwan, noting that shared political will on this problem is much stronger than in the recent past. Australia, however, places greater stock on the need to engage other partners on a range of other regional contingencies, irrespective of their support for allied forces in a Taiwan crisis. From Canberra’s perspective, premising defence engagement with Southeast Asian partners on a single high-end scenario oversimplifies regional strategic dynamics and alignment choices. By contrast, investing time and resources in collective arrangements that are unlikely to pay dividends in a Taiwan contingency is viewed as an unattractive prospect by many American strategists.

- There is no consensus among, or between, Australians and Americans on the degree to which Southeast Asian states share allied assessments of the regional order. Canberra and Washington appreciate the need to better address regional sensitivities surrounding new alliance initiatives, particularly in countries like Indonesia. But the extent to which regional countries identify with key assumptions about the declining strategic environment, and what diplomatic legwork is required to bring their outlooks into greater alignment with Australia and the United States, is debated. By and large, Americans tend to be more supportive of the argument that Southeast Asian nations are resigned to the local hard-power realities of US-China competition and, in many cases, quietly supportive of initiatives designed to shore-up a favourable balance of power. Australian assessments are far more cautious. Rather than waiting for regional partners to catch-up to allied balancing preferences, Canberra aims to pursue adjustments to regional security architecture at a pace that these states can cope with and in a way that provides them with strategic benefits. Southeast Asian countries, for instance, are interested in the maritime security assistance that allies can offer, even if this is not driven by converging alignment preferences. Australians and Americans both agree that misplaced and untested assumptions about regional political and strategic preferences risk constraining allied activities in a real contingency.

- There is a shared appreciation of the need to reform US-Australia alliance structures to deepen bilateral integration and advance collective defence objectives more effectively. Deepening cooperative strategic and contingency planning between Australia and the United States, and trilaterally with Japan, is a top a priority. Such initiatives should establish shared risk perceptions and thresholds for action across a range of potential conflict or sub-conflict scenarios. More effective processes for triaging intra-alliance requests on force posture initiatives are underway but need to be replicated in other areas – such as defence industrial integration and geoeconomic strategies – to maximise the collective effects of emerging alliance activities. For Canberra, such reforms are essential to offsetting bandwidth constraints, focusing US attention, and minimising the implementation risks that come with a burgeoning alliance agenda.

- Both sides recognise the barriers to this agenda are more political than technical in nature. Australian and US risk perceptions in any given scenario will rarely align perfectly, not least because Australia, as a middle power, is far more vulnerable to Chinese coercion. This reinforces the need to strengthen processes for identifying and reconciling different political and military risk calculations ahead of a crisis. This is not only a matter of strategic alignment, but one of operational significance. Failure to develop a shared understanding of the political significance of combined military capabilities or force posture initiatives in a range of different scenarios could have significant implications for the alliance’s ability to employ these assets before a crisis, as a means of crisis management, or during a conflict. This is especially relevant with respect to the prospective deployment or rotation of US bombers and submarines to Australian facilities. Only after broad consensus on these issues is reached can questions of how, when, and why to apply conventional force in different scenarios be properly addressed.

- One way of addressing these challenges might be to explore options for developing combined military advice for political consideration. Officials from both countries could be tasked with stress testing and reconciling bilateral assumptions on a range of potential combined planning initiatives, before presenting these findings for non-binding political review. This sort of process underpins NATO’s Flexible Response concept, and its measured response to the conflict in Ukraine offers some evidence of the benefits a common understanding of political thresholds and escalation risks. Though alliance dynamics in the Indo-Pacific are not comparable to those in Europe, delineating the limits of alliance consensus on any given contingency is a necessary step in advancing a sustainable collective defence agenda.

- As the risks of high-end conflict become more pronounced, US-Australia military exercises will need to strike a balance between serving as vehicles for deterrence signalling and providing testbeds for new concepts and strategies with suitable bandwidth for failure. There is concern on both sides that military exercises in their present form are not well calibrated to influence China’s strategic calculus, with some arguing that exercises do not simulate the kinds of operational challenges that the alliance would face in a high-end conflict. Conversely, there is political value in exercising as a means of signalling collective intent to develop solutions to specific operational or strategic challenges, even if initial concepts fail. When framed properly, the growing complexity of multilateral exercises like Talisman Sabre can provide valuable deterrent signals and innovation opportunities.

Defence industrial cooperation

According to US supporters of a reform agenda, Canberra should focus on precise requests for technology transfers and regulatory changes that can generate capability payoffs now and, hopefully, generate systemic change over the long term. Targeted requests will help to create the demand signals necessary within US industry and government for the transfer or production-at-scale of specific defence items.

- Australia and the United States see expanded defence industrial cooperation as key to enhancing the credibility of collective deterrence in the region. Deepening industrial base integration, reforming export controls, updating technology sharing and transfer arrangements, and accelerating processes for capability co-development are essential in this regard. These initiatives are not only about improving US and Australian force structure. Deeper defence industrial cooperation is also needed to underwrite expanding bilateral force posture initiatives, particularly in the development of a shared logistics, sustainment, and maintenance capacity in Australia.

- There are formidable obstacles to deepening bilateral defence industrial integration. These are primarily cultural in nature, though they manifest in a wide range of longstanding legal, regulatory, institutional, and bureaucratic barriers within the US system. Despite Australia’s efforts in recent years to drive a conversation about reforming bilateral defence industrial practices with US counterparts, these barriers have proven highly resistant to change. The Biden administration’s emphasis on closer coordination and integration with allies and partners on defence technology issues, not least through the AUKUS arrangement, is a welcome development with the potential to make progress.

- Without sustained and disciplined leadership from the White House, Congress, and State Department, progress on defence industrial integration will be incremental at best. Principals can drive these efforts through the creative implementation of existing authorities – such as the expanded National Technology and Industrial Base and defence cooperation treaty provisions – as well as by spotlighting defence industry issues on the annual AUSMIN agenda. Advocacy on these issues with Congress is one means for Australian officials to generate political support for targeted US reforms. At the working level, American policymakers should present senior officials with clear and actionable recommendations to prioritise and fast-track requests for specific capabilities and technologies to trusted allies like Australia.

- Ongoing bilateral conversations on the nature and requirements of defence industrial and technology integration need to evolve from dealing in generalities to specific requests for change accompanied by clear strategic policy rationales. Australia’s general frustrations with the lack of progress on export control reform, particularly through the NTIB, is well known, albeit not always understood. According to US supporters of a reform agenda, Canberra should focus on precise requests for technology transfers and regulatory changes that can generate capability payoffs now and, hopefully, generate systemic change over the long term. Targeted requests will help to create the demand signals necessary within US industry and government for the transfer or production-at-scale of specific defence items. This should be accompanied by efforts to spotlight acute barriers to implementation of agreed on initiatives as a way of building the case for reform and further streamlining bilateral processes for close allies like Australia.

- Bolstering the collective capacity to produce long-range, precision-guided munitions is widely considered as the most immediate priority for defence industrial integration efforts. Given the United States’ limited production capacity and the growing pressure on existing munitions stockpiles, the development of alternative sources of supply is essential for sustaining conventional deterrence vis-à-vis China. Notably, the depletion of munitions stocks during counter-ISIS air operations over Iraq and Syria in 2015 exposed the operational risks of shortfalls of critical items, even in a low-intensity conflict. Friend-shoring the production of common munitions and other key items in Australia will not only help to bolster US and Australian stockpiles within the Indo-Pacific area of operations, but could also provide other trusted partners with supply.

- Canberra and Washington should pursue two lines of effort to boost Australia’s guided munitions capacity. First, they should leverage existing US authorities, such as Title III of the Defense Production Act, to drive investments in workforce and production capacity for priority needs. Second, they should work together to expand Australia’s sovereign manufacturing capacity through intellectual property and technology sharing arrangements designed to realise Canberra ambition to develop a Guided Weapons and Explosive Ordinance (GWEO) enterprise. Noting Australia’s frustrations with the NTIB’s inefficiencies, revisions are required to maximise the participation of Australian industry in collaborative defence industrial and technology projects. At present, the complexity and sheer volume of regulatory hurdles are big disincentives for Australian industry to advance these initiatives within the US system.

***