Executive summary

Regardless of the 2024 presidential election result, US efforts to buffer against Chinese encroachments will continue to shape the contours of Washington’s and by extension, Canberra’s foreign policy calculus in the Pacific Island states for years to come. However, other facets of US statecraft should not be obscured by hard security priorities, especially people-to-people ties. This policy brief stresses the imperative for the United States to coordinate with Australia to develop new cultural and intellectual platforms by which Americans across various sectors can organically forge personal connections with Pacific Islanders.

As one of the United States’ closest allies, Australia can provide guidance to Washington on how to capitalise on people-to-people interactions as a mechanism to strengthen ties with the Pacific Islands. There is an obvious strategic imbalance between the two countries, especially in Melanesia, which is Australia’s default subregional focus and where the US diplomatic network remains most underdeveloped. In recent years, Canberra has significantly sharpened its diplomatic focus in the Pacific, through initiatives such as: accepting up to 3,000 citizens of Pacific Island nations and Timor-Leste every year to permanently live in Australia through its Pacific Engagement Visa scheme; expanding the Pacific’s telecommunications network via the launch of the Cable Connectivity and Resilience Centre in July 2024; and amplifying sports diplomacy for both men’s and women’s elite rugby leagues by producing the Australian-Pacific Rugby Union Partnership (APRUP).1

As one of the United States’ closest allies, Australia can provide guidance to Washington on how to capitalise on people-to-people interactions as a mechanism to strengthen ties with the Pacific Islands.

This paper concludes that fostering people-to-people exchanges will bolster US staying power in the region for three reasons. First, these linkages will allow Americans to gradually narrow knowledge gaps on the United States’ historical ties and its role in the Pacific Island countries. Second, they will demonstrate to Pacific stakeholders that Americans are sincerely invested in the issues that their region confronts that fall outside the bounds of mainstream geopolitics. Finally, Pacific Islanders, including the vibrant diaspora communities in both countries, will feel more empowered to share their stories on their terms.

Policy recommendations

- The United States should develop opportunities for American and US-based foreign policy observers, academics, entrepreneurs and practitioners, especially early in their careers, to pursue educational and research fellowships that raise awareness about the challenges the Pacific Islands face, as well as their regional aspirations.

- The United States and Australia should collaborate on media literacy and exchange programs to integrate Pacific voices into their media landscapes and ensure that their respective Pacific Island diaspora communities, which are arguably both countries’ enduring strengths in the region, can stay connected to their home country or territory.

- The United States and Australia should collaborate on ways to incorporate sports diplomacy into their engagement with the Pacific Island countries and diaspora communities.

Introduction: A collective amnesia and a short attention span

The United States holds strong foundations in the Pacific with the state of Hawaii and three of its territories — Guam, American Samoa and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI) — situated in the Pacific Ocean.2 Washington also maintains a Compact of Free Association (COFA) with three sovereign countries of the Freely Associated States (FAS): the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI) and the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) since 1982 and the Republic of Palau since 1986.3 The three Compact countries offer tremendous strategic and defence benefits to the United States by providing unimpeded military access and allowing the construction of bases such as the Ronald Reagan Ballistic Missile Defence Test Site located in the RMI.4 In return, COFA citizens can pursue employment in the United States and its territories; serve in the US military; and are eligible for certain federal aid programs such as disaster relief funds and educational grants.5 All of the COFA nations, Guam, and the CNMI are located north of the equator in Micronesia, which is the subregion where the United States has historically devoted the most strategic attention and economic resources. Meanwhile, Hawaii and American Samoa are located in the Polynesian subregion, where New Zealand is informally considered the main partner for most of these countries.

In recent years, Pacific Island leaders have noted subtle differences in how US officials and Pacific Islanders perceive the United States’ relationship with the Pacific Island countries. For example in 2019, then-Fijian Ambassador to the United States Naivakarurubulavu Solo Mara remarked that there is a “collective amnesia that sets in on every [US] delegation that arrives on our shores.”6 Mara added that Pacific Islanders are under the impression that Americans “act like strangers to [the Pacific islands]” despite the United States’ distinctive geographical, historical and cultural ties to the region.7 Multiple officials from the Pacific Islands have also expressed frustration with the lack of US governmental personnel in their respective countries, and characterised US regional engagement as inconsistent.8

Washington is acutely aware of these concerns, and senior officials under the Biden administration have acknowledged them publicly. On multiple occasions, US Deputy Secretary of State Kurt Campbell has noted that Washington has been hampered by diverting attention away from the Indo-Pacific to address challenges in other regions.9 In January 2022, he hinted that should a “strategic surprise” manifest in Asia, it would likely arise from the Pacific Islands region.10 This bandwidth dilemma is Washington’s Achilles heel, creating opportunities for other actors to exploit the lack of US focus. In 2022, the United States and Australia learned this difficult lesson.

The opportunity cost of putting the Pacific Islands on the back burner

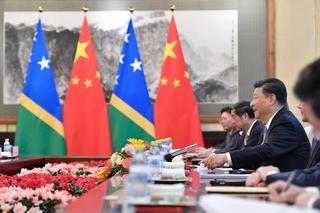

Since President Biden took office in January 2021, Beijing has demonstrated its ability to project coercive measures across the Pacific Island region, challenging US resolve to meet Pacific needs without undermining the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF)’s pledge to “deepen regionalism and solidarity,” in its 2050 Strategy for the Blue Pacific Continent.11 This became most apparent in March 2022 when the language of the “framework agreement” between the Solomon Islands and China was leaked online a month before the two countries formalised a security arrangement.12 The agreement highlighted Beijing’s capacity to surprise Canberra and Washington, corroborating concerns about China’s aspirations to sequentially cement its security presence in the Pacific.13 Despite appeals from Australian and American officials to Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare and other senior officials to reconsider the cooperative agreement, both countries failed to persuade him to do so.14

The signing of the agreement was a necessary wake-up call for both Australia and the United States. Australia’s then-Shadow Minister for Foreign Affairs Senator Penny Wong accused then-Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison of significantly weakening Australia’s position in the Pacific, declaring the pact as the “biggest foreign policy blunder that [Australia] has seen since World War II.”15 In Washington, the security agreement compelled officials to recognise the opportunity costs of neglecting the Pacific Islands.

In late April 2022, the Biden administration sent a delegation led by Kurt Campbell, then the Indo-Pacific coordinator at the National Security Council, to the Pacific, including the Solomon Islands. After the trip, the White House announced new bilateral initiatives and commitments between the United States and the Solomon Islands, stating it would “have significant concerns and respond accordingly” if the security agreement allowed China to establish a permanent military base in the future.16 This was a watershed moment that propelled the Biden administration to quickly shift its policy approach towards the Pacific Islands.

New rules of engagement in the Pacific under Trump 1.0 and Biden

Washington drew important lessons from the 2022 security agreement between the Solomon Islands and China. Most notably, that the United States must engage more frequently and consistently with the Pacific Island states. Given China’s ongoing diplomatic overtures in the region, US engagement in the Pacific Islands must take a hands-on approach that is predicated on upping the US regional presence.

Moreover, Beijing is determined to diminish Taiwan’s international space by courting its remaining diplomatic allies in the region. Since 2019, three Pacific Island countries — Kiribati and the Solomon Islands in 2019, and Nauru in January of this year — have broken diplomatic ties with Taipei and established relations with Beijing, leaving Taiwan with just three remaining allies in the region.17 More recently, China’s Special Envoy for Pacific Island Countries Qian Bo reacted strongly when a version of the PIF’s joint communique from this year’s summit inserted a sentence about Taiwan and the final version removed all mention of the self-governing island.18 According to The Australian, during the PIF summit, officials from the Solomon Islands were reportedly working at China’s behest to convince other PIF members that Taiwan should be prohibited from participating in next year’s summit, which will be held in their capital of Honiara.19 Considering these dynamics, which pose a challenge to US geostrategic interests, will far outlast the Biden administration, a key question is what the US relationship with its Pacific partners will entail once Biden leaves office in January 2025. Neither the Democratic nominee Kamala Harris nor Republican nominee Donald Trump have clearly outlined their policy direction in the Pacific Islands in a hypothetical future administration. It is therefore essential to examine how the Trump and the Biden administrations approached Pacific dynamics in more granular detail.

Since 2019, three Pacific Island countries — Kiribati and the Solomon Islands in 2019, and Nauru in January of this year — have broken diplomatic ties with Taipei and established relations with Beijing, leaving Taiwan with just three remaining allies in the region.

First, Washington under the Trump administration made notable changes to how it manages its relationship with the Pacific Islands. As evidenced through the rollout of the 2017 US National Security Strategy and the ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific’ strategy, this can largely be attributed to increased competition between the United States and China.20 With China’s assertive behaviour unsettling Washington and other capitals across the Indo-Pacific, the Trump team determined that blunting Chinese manoeuvring should be the new fulcrum of US strategy in Asia. Combatting the challenges associated with this new geopolitical paradigm ensured that Pacific affairs would remain on Washington’s foreign policy agenda. Thus, the Trump administration expanded ways to refine US engagement with the Pacific Islands, and it achieved some milestones. First, in 2018, they established the first directorship within the National Security Council whose portfolio solely entails Oceania and the Pacific Islands.21 In November of the same year, during the 2018 Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) meeting in Port Moresby, then-Vice President Mike Pence confirmed that the United States is collaborating with Papua New Guinea (PNG) and Australia to refurbish the decaying Lombrum naval base on Manus Island.22 A year later, then-Secretary of State Mike Pompeo became the first sitting secretary of state to visit the FSM.23 Shortly thereafter, Trump hosted all three leaders from the FAS at the Oval Office, which was the first meeting of its kind.24 A few months before the 2020 presidential election, Washington formally laid the groundwork to extend the economic assistance via COFA.25 Finally, news came out that the United States, along with Japan and Australia, intended to pursue a fibre-optic cable project for Palau.26

Since Trump’s departure in 2021, the Biden administration has accelerated efforts to reengage with the Pacific Islands, especially in response to the Solomon Islands and China finalising their security pact in 2022. First, the United States quickly reopened its embassy in the Solomon Islands; established embassies in Tonga and Vanuatu; and expressed its intention to construct another embassy in Kiribati.27 Second, administration officials and congressional Republicans and Democrats are courting officials from the Pacific Islands more frequently. The most recent high-profile visit in the Pacific Islands was made by Kurt Campbell, where he attended the 2024 iteration of the PIF leadership summit in Tonga; a commemoration ceremony of America’s newest embassy in Vanuatu; and a set of bilateral strategic dialogues in New Zealand.28 In September 2022, the Biden administration convened the first US-Pacific Island Country Summit in Washington, DC, presenting the United States’ first Pacific Partnership Strategy and hosting a second leadership summit the following year.29 While this particular development received limited media attention, last September, Biden upgraded US relations with Niue and the Cook Islands by officially recognising them as sovereign states (both countries are part of a free association with New Zealand).30 In March 2024, after months of domestic gridlock over funding, the US Senate successfully authorised US$7.1 billion in additional funding for the COFA nations over the next two decades.31 Finally, Guam and American Samoa became associate members of the PIF, although the CNMI’s application to upgrade their status to associate membership is still pending.32

Potential setbacks for the next US president

The following section assesses the political impediments that the next US president should anticipate in advancing closer ties with the Pacific Island countries once he or she takes office.

Kamala Harris

At the macro level, a hypothetical Harris administration is likely to duplicate Biden’s foreign policy agenda in Asia, building on her predecessor’s accomplishments. However, as Harris asserted during her debate with former President Trump, she is not Biden, and she has the prerogative to adjust Washington’s policy agenda.33 While it is sensible for her to tout her predecessor’s accomplishments, Harris will also need to address instances where the Biden administration is perceived to be falling short in the Pacific. For instance, Biden was slated to be the first sitting president to visit a Pacific island nation — specifically PNG — in May 2023, but he cancelled his trip at the last minute to reconcile a debt ceiling crisis with congressional leaders.34 While this incident is not a direct reflection of Harris, if she visits the Pacific Islands, local officials will likely approach her visit with scepticism. A more recent example involves delays in COFA funding, such as veterans’ benefits for citizens from the FAS who have served in the US military.35 It remains to be seen how significant the budgetary matters around COFA will be next year, but Harris and her team may have to provide additional explanations about why the funds are running behind schedule. The administration may craft its messaging to reflect that these challenges preceded her term in office, thereby tacitly distancing herself from COFA-related stumbling blocks.

Donald Trump

Considering that Trump is more mercurial in nature, it is difficult to predict what exactly US cooperation with the Pacific Islands will look like should he be re-elected. One former Trump official suggested that, as president, he would likely widen the scope of US partnerships with the Pacific.36 However, any daylight between Pacific Island leaders and Washington under a Trump administration will likely centre on how they prioritise climate change and related environmental issues. As outlined in the Pacific Islands Forum’s 2050 Strategy for the Blue Pacific Continent and the 2018 Boe Declaration, climate change is a formidable force that is threatening Pacific livelihoods, and has been labeled as the region’s existential challenge.37 Pacific Islanders, including the leaders from Fiji, Tuvalu and the RMI expressed great disappointment with Trump’s decision to withdraw from the Paris Climate Accords in 2016.38 During Trump’s 2019 meeting with the FAS leaders at the White House, Palauan President Tommy Remengesau Jr. indicated that the Pacific leaders deliberately avoided discussing climate change because of Trump’s scepticism of it.39 While they catered their talking points to accommodate Trump’s personal stance, the leaders did discuss pressing matters related to the environment like Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) fishing.40 Although Biden re-entered the United States to the Paris Climate Accords, Trump’s 2024 election campaign has indicated that the former president will once again withdraw America from the agreement again if he wins re-election.41 Trump’s consistency on his stance regarding climate issues is suboptimal for Pacific Island states. From their vantage point, this will validate their anxieties that he does not resonate with their number one concern for generations to come.

Taking cues from Australia

The United States should work closely with Australia to expand its presence in the Pacific Island countries. With diplomatic postings in all Pacific Island states, Australia has a more sophisticated understanding of where the Pacific stands on regional issues and priorities.42 According to the Lowy Institute’s Pacific Aid Map, Australia is the world’s largest provider of aid to the Pacific Island nations, with a 40% share of Official Development Finance.43 Moreover this year, under Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, Australia has further deepened its ties with the Pacific. Notably, PNG Prime Minister James Marape became the first Pacific leader to make an address at Parliament House.44 Additionally, Australia’s Minister for International Development and the Pacific Pat Conroy became the first politician to be appointed to the Cabinet with direct responsibility for the Pacific Islands.45 Finally, the Falepili Union, a groundbreaking security and climate agreement brokered by Australia and Tuvalu last year, came into effect in August 2024.46

It would appear sensible for Canberra and Washington to coordinate on initiatives for the Pacific Islands. Beyond their aligned strategic interests, Australia and the United States can use their diplomatic strengths to improve the quality of life for Pacific people through soft power mechanisms. Joint cooperation on certain ventures could be beneficial, provided both countries make good-faith efforts to minimise inefficiencies and bandwidth issues through duplicate lines of effort. However, it is also worth considering whether close coordination would be more of an asset or a liability for Canberra, given that Pacific leaders fear that both countries are stepping up their activism primarily to undermine — and complicate — Chinese revisionist movements in their region. As strategic competition continues to define US-China relations, this geopolitical pressure significantly impacts Pacific regional stability. This is why in March this year, Fijian Prime Minister Sitiveni Rabuka issued a clarion call for the Blue Pacific to cultivate a “zone of peace,” and in May 2023, the Cook Islands Prime Minster Mark Brown remarked that he has no desire to see his region morph into “an area of adversarial competition by our development partners.”47

Although Australia prides itself on being a reliable partner for its Pacific neighbours, its deliverables face increased scrutiny in a contested strategic environment, especially if Australia’s gestures are perceived to be driven by geostrategic imperatives — subtle or otherwise — or to be dictated by US efforts to outcompete China on all fronts.48 The fact that the freshly-minted Pacific Policing Initiative (PPI), which is an Australian initiative, was unanimously endorsed by Pacific leaders during the annual PIF leadership summit in late-August, reinforces this point.49 While Canberra relished in its diplomatic win, not all Pacific leaders immediately threw their weight behind the initiative. For example, Vanuatu Prime Minister Charlot Salwai posited that the PPI is an “important initiative,” but Pacific Island nations need to ensure that Pacific priorities guide the PPI and it is not designed to marginalise other big-power players like China from region-led initiatives.50 On the margins of the summit in Nuku’alofa, Tonga, a side conversation between Prime Minister Albanese and Kurt Campbell captured on video revealed that Washington paused a policing deal it was developing with its Pacific partners at the request of the Australian Ambassador to the US Kevin Rudd.51 As Kurt Campbell aptly put it, the United States gave “[Australia] the lane” to shepherd the PPI.52 This incident reveals how Australia and the United States must carefully frame the narrative behind their activism — joint or otherwise — in the Pacific Islands.

The benefits far outweigh the risks of Australia and the United States working in concert with each other to bolster regional connectivity in the Pacific.

Pacific leaders have historically enjoyed exercising their agency by leveraging relationships with China and Western countries to secure aid and attention, sometimes yielding political dividends. Thus, the effectiveness of US and Australian initiatives will depend on how both countries coordinate and pitch their efforts to Pacific stakeholders. If leaders believe that this outreach is not sensitive to regional concerns and/or is too narrowly focused on countering China, they may be less receptive. From a Pacific perspective, demanding outright Chinese exclusion from enterprises and initiatives could be antithetical to meeting their needs and addressing key priorities. It may also signal that the two countries, especially the United States, are unwilling to educate themselves on the complexities of China’s growing geostrategic footprint in the region. Finally, considering the Pacific’s significant capacity and resource constraints, Australia and the United States need to be careful not to overstretch these countries’ ability to absorb too much diplomatic attention.

These caveats aside, the benefits far outweigh the risks of Australia and the United States working in concert with each other to bolster regional connectivity in the Pacific. As Pat Conroy correctly noted earlier this year, not only do the two countries and the Pacific Islands occupy part of the same neighbourhood, but the fate of their security and aspirations are deeply intertwined.53

Policy recommendations

Irrespective of who wins the 2024 US presidential election, Washington and Canberra should make sincere efforts to expose their citizens to the Pacific Islanders’ way of life by visiting their region. Below are three recommendations by which the United States and Australia should coordinate to promote lasting exchanges, so that Pacific Islanders can feel genuinely represented in US statecraft in Asia.

1. The United States should develop opportunities for American and US-based foreign policy observers, academics, entrepreneurs and practitioners, especially early in their careers , to pursue educational and research fellowships that raise awareness about the challenges the Pacific Islands face, as well as their regional aspirations. While there are existing programs that bring talented students and professionals from the Pacific Islands to the United States, such as Johns Hopkins SAIS’ US-Pacific Institute for Rising Leaders and the US State Department’s upcoming Youth Ambassadors Program for the East Asia and the Pacific region, there are a lack of parallel programs for American students and young professionals to seek similar immersion opportunities in the Pacific Islands. Thus, the United States should consult with Australian stakeholders on how it can establish fellowships, scholarship programs and other forms of people-to-people linkages that will focus on professional development, youth and women’s empowerment, and cultural literacy opportunities in the Pacific Islands.54 The United States could consider establishing an initiative that mirrors the highly successful New Colombo Plan (NCP), which was launched in 2014 by Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.55 The NCP provides students the opportunity to pursue studies, language programs and internships in the Indo-Pacific, including the Pacific Islands.56 Rectifying the asymmetry in exchanges is essential for Americans to gain first-hand experiences in the Pacific Islands and demonstrate that the United States is determined to make an equal effort in forging deeper and lasting connections with its Pacific partners.57

2. The United States and Australia should collaborate on media literacy and exchange programs to integrate Pacific voices into their media landscapes and ensure that their respective Pacific Island diaspora communities, which are arguably both countries’ enduring strengths in the region, can stay connected to their home country or territory. This can be achieved through media exchanges that create opportunities for local American and Australian news outlets based in areas with a significant Pacific Islands diaspora population to collaborate with reputable Pacific and Australian media outlets with a strong presence in the Pacific. For instance, in February of this year, the Public Broadcasting Series (PBS) released an hour-long documentary, which explores one of the RMI’s biggest diaspora communities in the continental United States, specifically in Springdale, Arkansas.58 Similarly, in early-May, King 5, a local news station in Seattle, interviewed local Pacific Island residents from American Samoa, Fiji, Hawaii, RMI and Tonga to commemorate Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Heritage Month.59 To encourage more media initatives of this kind, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC), which has a strong foothold in the region and is the most trusted international media network in the Pacific Islands, should partner with smaller Australian and American media outlets that have limited resources to connect with a diverse array of Pacific leaders and members of civil society.60 Over time, this collaboration can help integrate more Pacific voices in the media landscapes of both countries, creating storytelling that will resonate with diaspora communities.

3. The United States and Australia should collaborate on ways to incorporate sports diplomacy into their engagement with the Pacific Island countries and diaspora communities. Canberra has already made progress in this area by offering to finance up to A$600 million for PNG to field a team within the Australian National Rugby League (NRL) in Port Moresby.61 With the next two summer Olympic Games set to take place in Los Angeles in 2028 and Brisbane in 2032, there is a timely opportunity for the two countries to embrace sports diplomacy and explore how Pacific voices can be incorporated into both countries’ Games.62 For example, Americans who are part of organising the Los Angeles Games could travel to US territories or the FAS to involve up-and-coming athletes and coaches from those areas into marketing campaigns and promotional events. Another way that Australia and the United States can strengthen bonds with their Pacific partners would be to establish a scholarship program for a select number of Pacific Islanders from all subregions and diaspora communities to volunteer for one of the Games. Spotlighting Pacific individuals will strengthen ties between Australia, the United States and the region, and leverage sports diplomacy to leave a lasting impression of the potency of American and Australian soft power.

Conclusion: Actions, not just words

The United States must strengthen its soft power projection and elements of its public diplomacy by amplifying people-to-people exchanges as a principal component of outreach in the Pacific Island countries. This brief’s recommendations share a common goal: to bolster US visibility in the Pacific Islands, a move that would be welcomed by Australia and Pacific stakeholders who have long called for greater US engagement in the region.63 While it is likely that the Pacific Islands will not be the central component of US strategy in Asia under a future Harris or a Trump administration, the United States and Australia are well-positioned to collaborate to generate new pathways by which to enhance people-to-people activities. More importantly, genuine efforts to expand people-to-people linkages that are not solely framed in geopolitical terms will demonstrate to Pacific Islanders that both countries resonate with Pacific stories and voices. The pursuit to forge closer ties, grounded on a shared history and future, is one that should not have an expiration date and should no longer be subordinated to other priorities.

Addendums

US and Australian diplomatic posts and missions in the Pacific Islands

Disclaimer: This chart excludes US states and territories in the Pacific (Hawaii, Guam, American Samoa, and the CNMI)

a. “US opens embassy in Vanuatu, latest step in China competition,” Reuters, July 19, 2024, available here: https://www.reuters.com/world/us-opens-embassy-vanuatu-latest-step-china-competition-2024-07-18/.

List of subregions in Oceania

.jpg?rect=0,80,3000,1989&fp-x=0.5&fp-y=0.44772296905517583&w=320&h=212&fit=crop&crop=focalpoint&auto=format)