Australia seems on the brink of embracing space in a coordinated manner, but how should we do it?

This week, the Australian government released three reports to help chart the future of Australia’s space industry. Their conclusions will feed into the review of Australia’s space industry underway by former CSIRO head Dr Megan Clark.

The reports examine Australia’s existing space capabilities, set them in the light of international developments, and identify growth areas and models for Australia to pursue. The promise is there:

- Australia has scattered globally competitive capabilities in areas from space weather to deep-space communication but “by far the strongest areas” are applications of satellite data on Earth to industries like agriculture, communications and mining

- Australian research in other sectors like 3D printing and VR is being translated to space with potentially high payoffs

- global trends, including the demand for more space traffic management, play to our emerging strengths

- the prize for success is real - the UK currently has an A$8 billion space export industry, and anticipates further growth.

While it is not the first time the government has commissioned this type of research, the updates are welcome given the fast pace of space innovation. Taken together they paint a picture of potential for the future of Australian space and a firm foundation for a space agency.

The rules of the game

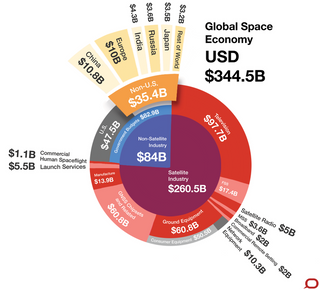

The Global Space Industry Dynamics report from Bryce Space and Technology, a US-based space specialist consulting firm, sets out the “rules of the game” in the US$344 billion (A$450 billion) space sector.

It highlights that:

- three quarters of global revenues are made commercially, despite the prevailing perception that space is a government concern

- most commercial revenue is made from space-enabled services and applications (like satellite TV or GPS receivers) rather than the construction and launch of space hardware itself

- commercial launch and satellite manufacturing industries are still small in relative terms, at about US$20.5 billion (A$27 billion) of revenues, but show strong growth, particularly for smaller satellites and launch vehicles.

The report also looks at the emerging trends that a smart space industry in Australia will try and run ahead of. Space is becoming cheaper, more attractive to investors and increasingly important in our data-rich economy. These trends have not gone unnoticed by global competitors, though, and the report describes space as an increasingly “crowded and valuable high ground”.

Five steps Australia can take to build an effective space agency

What is particularly useful about the report is its sharp focus on the three numbers that determine commercial attractiveness:

- market size

- growth

- profitability.

The magic comes through matching these attractive sectors against areas where Australia can compete strongly because of existing capability or geographic advantage.

The report suggests growth opportunities across traditional and emerging space sectors. In traditional sectors, it calls out satellite services, particularly commercial satellite radio and broadband, and ground infrastructure as prime opportunities. In emerging sectors, earth observation data analytics, space traffic management, and small satellite manufacturing are all tipped as potentially profitable growth areas where Australia could compete.

The report adds the speculative area of space mining as an additional sector worth considering given Australia’s existing terrestrial capability.

It is encouraging that Australian organisations have anticipated the growth areas, from UNSW’s off-earth mining research, to Geoscience Australia’s integrated satellite data to Mt Stromlo’s debris tracking capability.

Australian capabilities

Australian capabilities are the focus of a second report, by ACIL Allen consulting, Australian Space Industry Capability. The review highlights a smattering of world class Australian capabilities, particularly in the application of space data to activities on Earth like agriculture, transport and financial services.

There are also emerging Australian capabilities in small satellites and potentially disruptive technologies with space applications, like 3D printing, AI and quantum computing. The report notes that basic research is strong, but challenges remain in “industrialising and commercialising the resulting products”.

The concern about commercialisation prompts questions about the policies that will help Australian companies succeed.

Should we embrace recent trends and rely wholly on market mechanisms and venture capital Darwinism, or buy into traditional international space projects?

Do we send our brightest overseas for a few years’ training, or spin up a full suite of research and development programs domestically?

Are there regulations that need to change to level the playing field for Australian space exports?

Learning from the world

Part of the answer is to be found in the third report, Global Space Strategies and Best Practices, which looks at global approaches to funding, capability development, and governance arrangements. The case studies illustrate a range of styles.

The UK’s pragmatic approach developed a £5 billion (A$8 billion) export industry by focusing primarily on competitive commercial applications, including a satellite Australia recently bought a time-share on.

A longer-term play is Luxembourg’s use of tax breaks and legal changes to attract space mining ventures. Before laughing, remember that Luxembourg has space clout: satellite giants SES and Intelsat are headquartered there thanks to similar forward thinking in the 1980s. Those two companies pulled in about A$3 billion of profit between them last year.

Norway and Canada show a middle ground, combining international partnerships with clear focus areas that benefit research and the economy. Norway has taken advantage of its geography to build satellite ground stations for polar-orbiting satellites, in an interesting parallel with Australia’s longstanding ground capabilities. Canada used its relationship with the United States to build the robotic “Canadarm” for the Space Shuttle and International Space Station, developing a space robotics capability for the country.

The only caution is that confining the possible role models to the space sector is unnecessarily limiting. Commercialisation in technology fields is a broader policy question, and there is much to learn from recent innovations including CSIRO’s venture fund and the broader Cooperative Research Centre (CRC) program.

As well as the three reports, the government recently released 140 public submissions to the panel.

There is no shortage of advice for Dr Clark and the expert reference group; appropriate given it seems an industry of remarkable potential rests in their hands.