On 6 November 2023, Stephen Gageler was officially sworn in as the fourteenth Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia, replacing the retiring incumbent, Susan Kiefel. Despite the significance of this appointment, it received limited media attention in Australia. This stands in sharp contrast to the United States, where appointments of justices to the Supreme Court are highly politicised events that attract extensive national and international coverage, including in Australia.

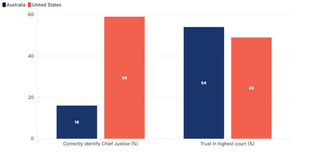

While Australians are less aware of the High Court’s processes and key players, they express greater confidence in their country’s top court than Americans do in the Supreme Court. Research on the Australian public’s awareness of the High Court is scant. However, a 2018 study revealed that only 16 per cent of Australians could correctly identify Susan Kiefel as the Chief Justice of the High Court. Nevertheless, a majority of Australians (53.7 per cent), irrespective of their political affiliation, agreed that “the High Court can generally be trusted to make decisions that are right for Australia as a whole.”

In the United States, the situation is notably different. A 2023 survey found that 59 per cent of Americans could correctly identify John Roberts as the Supreme Court's Chief Justice. Yet, Gallup polls show a dwindling level of approval for how the Supreme Court is handling its job. Between July 2020 and September 2021, public approval of the Supreme Court declined precipitously from 58 per cent to just 40 per cent — lower than at any time in at least the last 20 years. Support fell particularly sharply after a controversial decision in September 2021 when the Supreme Court allowed a restrictive abortion law in Texas to take effect. That decision foreshadowed the 2022 ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, the landmark judgement which overturned the constitutional right to an abortion. Approval of the Supreme Court continues to sit at this historic low. There is also a partisan divide in opinion of the Supreme Court’s performance: 62 per cent of Republicans approve of the court's performance, compared to just 17 per cent of Democrats.

Australians know less about their highest court, but trust it more

Sources: Australia, United States (trust), United States (identification)

What follows is an explainer of the establishment, structure and functioning of the Australian High Court and the US Supreme Court. From the nomination of justices to the influence of ideology in their decision-making, these factors may help to explain the significant differences in American and Australian perceptions of their respective countries’ highest courts.

The Supreme Court of the United States

When was the US Supreme Court created?

The Supreme Court is the highest court in the United States, meaning it is the final court of appeal for all federal court cases and state court cases that deal with federal law. The Supreme Court had its first sitting on 2 February 1790, in New York City, which served as the temporary US capital at the time. While the number of justices has changed throughout history from the original seven, it has remained at nine since 1869.

Court packing

The Constitution does not specify how many justices should sit on the US Supreme Court. Instead, the number is determined by legislation passed by Congress. Since the Supreme Court’s inception, there have been numerous instances of "court packing" — increasing the number of seats on the court to alter its ideological makeup — and "unpacking," which refers to reducing the number of justices.

The most infamous attempt at court packing occurred in 1937 when President Franklin D. Roosevelt, frustrated by the Court’s conservative majority, proposed legislation to appoint up to six additional justices. However, the public, media, and numerous Congress members viewed the bill as a blatant attempt to "pack" the court with justices who would rubber-stamp Roosevelt’s legislative initiatives, and it ultimately was never brought to a vote in Congress.

Modern court packing is less about simply adding more justices to the bench. Instead, the term is increasingly used to describe attempts to politically manipulate the court by adding justices that are perceived as either more conservative or liberal.

There is renewed interest from some Democrats in court packing as a way to counterbalance the current conservative majority on the Supreme Court. In May 2023, a group of Democrat lawmakers proposed a bill to add four seats to the US Supreme Court. However, the bill is unlikely to pass in the Republican-controlled House, and President Biden has warned that increasing the number of Supreme Court justices could “politicise it maybe forever, in a way that is not healthy."

What is the tenure of a US Supreme Court justice?

Justices can remain on the Supreme Court until they die, opt to retire, or are impeached and removed from office. Only one justice has ever been impeached, in 1804, in a controversial effort to have him removed for alleged partisanship, which ultimately failed.

The lifetime appointments of the Supreme Court continue to be a topic of debate. While Alexander Hamilton dismissed the “imaginary danger of a superannuated bench” during the Constitution’s drafting, critics today argue that the extended tenure of justices leads to various issues. A 2018 New York Times study found that since the Civil War, the average length of tenure for a Supreme Court justice has grown by about a decade, in large part because of longer lifespans. The same study also found that modern justices are appointed at younger ages, on average.

Throughout history, many unsuccessful attempts have been made in both the House of Representatives and the Senate to pass proposals for a constitutional amendment instituting judicial age limits, term limits, or both. A 2023 survey found that 74 per cent of the American public supports maximum age limits for Supreme Court justices and a group of Democratic senators introduced a bill in October 2023 to establish term limits for Supreme Court justices.

How is a US Supreme Court justice appointed?

When there is a vacancy on the Supreme Court, the president can nominate a replacement who must be confirmed by a simple majority of 51 senators. In recent times, this appointment process has attracted considerable public interest. Key portions of this procedure, such as the Senate Judiciary Committee hearings and the Senate debate, are broadcast on C-SPAN, allowing the public to closely follow the proceedings.

1. Pre-nomination considerations

While the Constitution does not specify qualifications for justices, every appointed justice has been a lawyer. In selecting a nominee, presidents are free to consult with, and receive advice from, whomever they choose. Typically, before making a nomination, a president may consult with Senate party leaders, members of the Senate Judiciary Committee, high-level advisers, House members, and special interest groups. For example, the Federalist Society (a conservative legal organisation) has played an important role in helping Republican presidents fill Supreme Court vacancies by providing presidents with a list of recommended nominees.

2. Senate Judiciary Committee review

Once the president has nominated someone, the responsibility shifts to the Senate Judiciary Committee. The committee conducts hearings to evaluate the nominee, during which witnesses, both supporting and opposing their nomination, present their views. Senators also question the nominee about their qualifications, past judgments, and judicial philosophy. The committee then votes on the nomination. They may recommend confirmation or rejection, provide no recommendation, or refuse to consider a candidate at all.

An example that highlights the power and discretion of the Senate in the process is President Barack Obama’s nomination of Merrick Garland to the Supreme Court in 2016. The Republican-led Senate, under Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, decided not to hold hearings on Garland's nomination, effectively refusing to consider Obama’s choice in an election year. However, this has never been a formal rule of the Senate, as evidenced by the nomination of Justice Amy Coney Barrett by President Trump in the 2020 election year.

3. Senate debate

After the committee makes its recommendation, the full Senate then debates the nomination. This debate can be ended by a vote from 51 senators.

4. Final senate vote

Once the debate ends, the Senate votes on the nominee. Confirmation of a nominee requires a simple majority of the senators present and voting, which is typically 51 votes. If the vote results in a tie, the Vice President casts the deciding vote.

Bork nomination

One of the most contentious and closely watched nominations took place when Republican President Ronald Reagan nominated Robert Bork to the Supreme Court in 1987. Bork’s nomination was among the first to be broadcast to the public. Bork faced intense scrutiny over his conservative views and past writings, with the Democratic-controlled Senate eventually rejecting Bork's nomination in a 58-42 vote. The rejection of Bork’s nomination gave rise to the term "borking," referring to the discrediting of a nominee’s reputation and views through political attacks, often on aspects seemingly unrelated to their role. This tactic has since been used by both Republicans and Democrats.

Who are the judges on the US Supreme Court?

John Roberts has served in the role of Chief Justice since 2005. Of the nine justices on the Supreme Court, three were nominated by Democratic presidents, while six were nominated by Republican presidents. A 2016 study found evidence of a loyalty effect, where justices were more inclined to rule in favour of the government of the president who appointed them.

In the 2022–23 Supreme Court term, major decisions were decided by a 6-3 ideological split, such as in Biden v. Nebraska, which struck down President Biden's student loan forgiveness program. However, despite the attention these decisions received, only five of the 58 decisions for that term followed this 6-3 split. This represents a decrease from the 14 decisions decided along an ideological split in the previous term, marking the lowest number of strictly ideologically split decisions in the past six years.

Justice Name |

Year Appointed |

Nominating Prime Minister |

Party of Prime Minister |

|---|---|---|---|

John Roberts (Chief) |

2005 |

George W. Bush |

Republican |

Clarence Thomas |

1991 |

George H.W. Bush |

Republican |

Samuel Alito Jr. |

2006 |

George W. Bush |

Republican |

Sonia Sotomayor |

2009 |

Barack Obama |

Democratic |

Elena Kagan |

2010 |

Barack Obama |

Democratic |

Neil Gorsuch |

2017 |

Donald Trump |

Republican |

Brett Kavanaugh |

2018 |

Donald Trump |

Republican |

Amy Coney Barrett |

2020 |

Donald Trump |

Republican |

Ketanji Brown Jackson |

2022 |

Joe Biden |

Democratic |

The High Court of Australia

When was the Australian High Court created?

The High Court of Australia is, as the name suggests, the highest court in Australia. Drawing inspiration from the US Constitution, the drafters of the Australian Constitution designed the High Court to be the ultimate umpire in a federal system. The High Court had its first sitting on 6 October 1903 in Melbourne, with its initial three justices growing to seven in 1913 and remaining so since. Originally, decisions from the High Court could be appealed to the Privy Council (an advisory body to the reigning monarch of the United Kingdom) in London, giving it a final say on Australian legal matters. However, appeals to the Privy Council were fully abolished by legislation in 1986.

What is the tenure of an Australian High Court justice?

High Court justices must retire once they reach the age of 70, though this mandatory retirement age was only introduced through a referendum in 1977. Former High Court Justice Michael Kirby praised fixed retirement, arguing in 2003 that “the regular appointment of younger people to a nation’s supreme court is a means of injecting new approaches and new ideas.”

The Constitution states that federal judges can be removed from their position for "proven misconduct or inability to perform their duties." However, no federal judge has ever been removed from office, and the High Court of Australia has never interpreted the meaning of these terms.

How is an Australian High Court justice appointed?

Under legislation, to be eligible for appointment, a person must either currently be or have previously been a judge of another court or have practised law for over five years. The Constitution states that justices “shall be appointed by the Governor-General in Council”— a provision that has been interpreted to mean that the Governor-General appoints justices based on the advice of the federal government.

The selection process for a High Court justice has been criticised for its lack of transparency. There is no formal application process. The only requirement is that the Commonwealth Attorney-General must consult with the attorney-generals of state governments. The Attorney-General may review candidates' past judgments, writings, and speeches, and often consults with senior judges and lawyers. Occasionally, Commonwealth Attorneys-General have issued papers or statements discussing selection criteria for appointments, emphasising considerations such as gender. Some recent Attorneys-General have also consulted with law school deans and organisations like Australian Women Lawyers. The court has attracted criticism for its homogeneity — every justice of the High Court of Australia since Federation in 1901 has been white, and all but six have been men.

Many issues have been noted with the appointment of High Court justices. Yet, the process is largely politically uncontroversial and is not used as a political bargaining tool by major parties, unlike in the United States. In Australia, the High Court, similar to the Supreme Court, decides cases that often generate political controversy. However, media commentary predominantly focuses on the individual justices' reasoning, as opposed to the government that was in power when they were appointed.

One possible reason is the limited public awareness about judges; for instance, no stage of the appointment process is televised. Australian governments have consistently emphasised that “merit” is the foundational principle for making judicial appointments. Former High Court Justice Bell speculated that if Australian justices were “subject to [the same] form of celebrity” as US Supreme Court justices, their roles would become more politicised, potentially tarnishing the public's esteem for the court and its legitimacy. Given the reaction to US Supreme Court decisions like Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, Australian politicians and the public might be hesitant to adopt an openly politicised appointment process.

Who are the judges on the Australian High Court?

Of the seven justices on the High Court, three were nominated by Labor Prime Ministers and four by Liberal Prime Ministers though there is far less public concern over ideological differences in the High Court.

Compared to the United States, there has been limited research into the relationship between the government’s nominations and the High Court justices’ decision making. However, a 2021 study found that justices appointed by Prime Ministers John Howard and Malcolm Turnbull were more likely to rule in favour of the federal government when the Prime Minister who appointed them was in office. Another study from 1995–2019 found that progressive High Court justices were typically appointed by the Labor party, while the Coalition were more likely to appoint conservative justices to the court.

Justice Name |

Year Appointed |

Nominating Prime Minister |

Party of Prime Minister |

|---|---|---|---|

Stephen Gageler (Chief) |

2012 |

Julia Gillard |

Labor |

Michelle Gordon |

2015 |

Tony Abbott |

Liberal |

James Edelman |

2017 |

Malcolm Turnbull |

Liberal |

Simon Steward |

2020 |

Scott Morrison |

Liberal |

Jacqueline Gleeson |

2021 |

Scott Morrison |

Liberal |

Jayne Jagot |

2022 |

Anthony Albanese |

Labor |

Robert Beech-Jones |

2023 |

Anthony Albanese |

Labor |