The COVID-19 pandemic sweeping the world brings more than illness, death and economic chaos; it brings existential and ethical dilemmas about how to provide care for the elderly who are most at risk of contracting the virus and who are dying as a consequence. The grim reality is that for the elderly, the novel coronavirus is “an almost perfect killing machine”.

This brief provides a look at how the United States and Australia are dealing with these critical issues.

What the data indicates

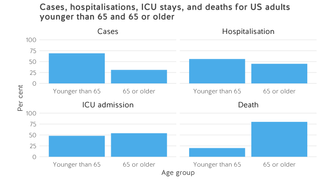

A report from the United States Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) confirms that, as in other badly affected countries such as China and Italy, COVID-19 is having the most severe impact among the elderly in America. The data show that 31 per cent of all cases, 45 per cent of hospitalisations, 53 per cent of ICU admissions, and 80 per cent of all deaths occurred among adults aged 65 or over, with the highest percentage of deaths among those aged 85 and older. For these oldest patients in America, the fatality rate is 10.5 per cent, ten times the national average.

In Australia, the majority of cases to date are reported in those aged 20 to 69 years, with only seven per cent in those aged older than 70. This is likely because the majority of confirmed cases are in people with a recent history of overseas travel. However, all of the eight deaths so far are people aged 70 years and older. The case fatality rate for patients in Australia aged 80 years and older is likely around 15 percent.

This is not surprising: the risk of infection increases with age simply because older people’s immune systems are less robust. Chronic conditions like cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease and diabetes – all of which are increasingly prevalent with age – also increase the severity of the virus. In disadvantaged population groups such as African Americans in the United States and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia, for whom the burden of chronic disease is higher, the risk of infection and death from COVID-19 increases at earlier ages and rises more quickly.

Nursing homes are becoming islands of isolation with shocking mortality rates

These shocking statistics mean that people in aged care are particularly vulnerable, especially those in residential facilities and nursing homes.

Across the United States, the number of cases of COVID-19 in nursing homes continues to spike. Late last week, at least 73 facilities in 22 states reported infections and at least 55 deaths (one quarter of all fatalities) occurred in these facilities. Indeed, it was an outbreak at a nursing home in Washington state that began in late February that jolted the United States into action and showed just how deadly the novel coronavirus can be in such settings, with at least 129 patients infected and 35 deaths.

Australia was alerted in the same way in early March, with infections at a residential aged care facility in Macquarie Park in Sydney’s north west that now accounts for three of the eight deaths nationally.

A variety of factors make nursing homes especially at risk: sick, older residents, poor staffing with minimal clinical training, and lax infection prevention — not helped because visitors are constantly coming and going. Residents live in close proximity, eating in communal spaces and often sharing rooms.

The Australian Royal Commission on Aged Care Quality and Safety has been shining a light on all these deficiencies and more since 2019. A recent issue brief from the non-profit Kaiser Family Foundation showed the situation is no better in the United States. It found almost 40 per cent of nursing homes across the United States had at least one infection control deficiency. Each year about 380,000 of America’s nursing home residents die from infections, and failure to prevent them is the leading cause of citations that state inspectors bring against nursing homes.

In both countries, the relevant government authorities have recently issued updated guidance for aged care facilities to limit exposure to coronavirus, but both countries are also facing challenges with the responses. Families are fearful that their loved ones (frail, perhaps with dementia) will not be well cared for if their visiting opportunities are curtailed. Poorly paid aged care workers with few benefits are reluctant to self-isolate if potentially exposed to the virus, and nursing home operators are complaining that they can’t meet additional staffing and costs required to boost infection control. One Australian estimate is that the additional cost of coronavirus to aged-care providers will be about $15 per resident per day.

In the United States, the situation is made more fraught because the Trump administration, responding to a push from the industry, has been actively working to relax regulations governing the United States’ nursing homes. This includes weakening a rule imposed by the Obama administration that required every nursing home to employ at least one specialist in preventing infections. Now staff are scared, exhausted, and increasingly, they and the people they care for are sick.

What can be learned from other countries?

One likely reason Italy has been hit so badly by coronavirus is that the country has the oldest average age in Europe and the second oldest in the world. But Japan, with the world’s oldest population, is an outlier with a surprising low number of reported cases and deaths. Germany, too, currently has a very low mortality rate (just 0.3 per cent), despite being severely hit by the pandemic and having a high percentage of citizens aged 65 and over.

Smoking and air pollution may be contributing factors: those with already damaged lungs are more likely to succumb to pneumonia. This could explain why China and Italy have been so vulnerable but does not account for Japan, which has the world’s ninth-largest cigarette market.

Smoking and air pollution may be contributing factors: those with already damaged lungs are more likely to succumb to pneumonia. This could explain why China and Italy have been so vulnerable but does not account for Japan, which has the world’s ninth-largest cigarette market.

Media articles from Italy suggest that there is a silent surge in fatalities in nursing homes, where many patients, already sick, die untested for the virus. At the same time, there are indications from the United States that low-paid home health aides are increasingly at the epicentre of the pandemic. In Australia, some 140,000 elderly receive community-based Home Care Packages, with limited ability to control exposure to coronavirus from service deliveries.

The ethical issues that must be confronted

In Italy, medical facilities are overwhelmed with COVID-19 patients while New York is described as being at a “tipping point”. Increasingly, doctors in some hard-hit cities are unable to care for everyone who seeks treatment amid a critical shortage of needed equipment such as ventilators. In such crisis situations, hospitals and doctors find themselves in the terrible position of having to decide who does and does not get access to intensive care facilities.

In the United States, it is quite public that such conversations are already happening with the goal of ensuring that hospitals have consistent, transparent guidance for patient care when lifesaving resources are scarce. These "crisis standards of care" prioritise the survival of the group over the survival of the individual patient during disasters. Still, as medical experts have noted, the primary criterion for rationing should be a negligible chance of survival, whatever a patient’s age.

In such crisis situations, hospitals and doctors find themselves in the terrible position of having to decide who does and does not get access to intensive care facilities.

The CDC outlines general principles, but it is ultimately up to individual hospitals, health systems and states to decide policy. The result is a patchwork system. States like New York and Minnesota have drawn up detailed guidelines for allocating resources. Others are yet to confront these tough issues.

If the ventilator shortages - and the pandemic generally - get as bad as the worst predictions, some postulate that palliative care will have to be offered to people who might have survived with intensive care. Essentially, doctors in the world’s wealthiest nation will be forced to ration care.

In Australia, there seems to be more optimism that hospitals can cope with the surge in demand, with plans drawn up for the provision of 2,000 more ICU beds. The topic of rationing is mentioned in passing, but whatever expert discussions are taking place are out of public view and do not involve public consultation.

In Italy, the peak body for intensive care medicine has published a grim guidance, stating that “resources may have to be used first for those with a higher probability of survival and, secondly, who has the most years of life left, and offer the maximum number of benefits to the majority of people”.

Some doctors in the United States have reached the same conclusions. “If we give scarce resources to those who don’t stand to benefit (and have a high chance of dying anyway), then not only will they die, but those with higher likelihood of survival (but require ventilator support) will also die,” says Professor Lydia Dugdale, director of the centre for clinical medical ethics at Columbia University in New York City. “It’s not fair to distribute scarce resources in a way that minimises lives saved.”

A comment from a British researcher serves as an appropriate endpoint for this brief summary of some very difficult issues: “You have to be really clear about what you are trying to achieve. Maybe you end up saving more people, but at the end you have got a society at war with itself. Some people are going to be told they don’t matter enough.”