Executive summary

This policy brief addresses the benefits and shortfalls of the Australian Defence Trade Controls Amendment Bill 2023.1 It argues that the proposed rules are necessary to strengthen Australia’s export control regime which is a key tenet of Australia’s protective security environment. The proposed rules will make Australian export controls bear a closer resemblance to the US system, facilitating AUKUS cooperation by making it easier for Australia to qualify for a US export control exemption by meeting US standards of sufficient comparability.

If the proposed rules pass, they are likely to prompt the US Congress to certify that Australia’s export controls system is comparable to that of the United States. If this occurs, the United States will provide Australia with a once-in-a-generation export control exemption. This exemption would remove barriers to defence technology trade and collaboration with US industry for Australian academia and industry — for example, the time and effort involved in applying for US export authorisations. Secondly, the proposed rules would create a licence-free environment for Australia, the United States and the United Kingdom to share Defence and Strategic Goods List (DSGL) controlled technology, whereas currently a licence is required. Combined, these two effects could also negate the issue of “ITAR taint”, referring to the fact that, at present, any technology co-developed with the United States “is ‘tainted’ by US design input, preventing all future uses, retransfers or even internal movement within a country’s own industrial base or supply chain network without permission from the State Department.”2

The proposed rules would also afford both Australian university and industry innovators and the Australian Government more control over foreign persons’ access to sovereign defence and dual-use technologies within Australia. The proposed rules are particularly relevant to universities and research and development organisations. They would provide a clear framework for identifying the international research collaborations that are within the national interest and that necessitate further investigation by the Australian regulator, Defence Export Control (DEC). Government scrutiny of foreign collaboration on technology research and development within Australia is not permitted under the current legal framework.

A further benefit, beyond the scope of this policy brief, is the expected economic benefits to the Australian industrial base. In the Government’s Impact Analysis on the proposed rules, the Government suggests the proposed rules will result in a net benefit on the Australian economy of A$614 million over a 10-year period when compared to the status quo.3

The bill will benefit Australia by making defence trade and technology collaboration with the United States, faster, less administratively burdensome and overall, more efficient, including in relation to AUKUS.

Conversely, Australian industry and academia have been vocal about the shortfalls of the proposed rules. Their concerns are focused on the additional compliance burdens they may place on Australian industry and the concern that this could disincentivise smaller innovative companies producing dual-use technologies from working in the defence sector.4 From the lens of academia, there is concern the proposed rules will unduly limit the ability to access leading international research, putting Australia behind other countries in future technology research and development.5 Additionally, Universities Australia, which is a peak body for the sector representing 39 Australian universities, argues that the proposed rules leave too much subordinate legislation, which they may or may not have input into.6 These are well-founded concerns that need to be addressed with the close involvement of industry and academia, including in the implementation, co-design and input into subsequent regulatory and policy updates.

The policy brief concludes that on balance the bill will benefit Australia by making defence trade and technology collaboration with the United States, faster, less administratively burdensome and overall, more efficient, including in relation to AUKUS. However, the bill undoubtedly involves concessions Australia must make to streamline defence trade with the United States. These concessions will come in the shape of additional compliance complexity for Australian industry and academia including the mandatory system, process and policy changes required to embed the proposed rules into business as usual.7

Recommendations

- The Australian Government should develop and include a mechanism which covers in-country transfers from Australian entities to a secondary Foreign Country List, inclusive of states with which Australia already has nascent defence industrial and technology collaboration relationships such as India, Japan, and South Korea.

- The Australian Government should consider an extension of the basic research exception for universities when operating at TRL 1-2 levels, with requirements for a permit only triggering if a project makes it past TRL2.

- The Australian Government should enable organisations to “screen” their own permanent employees captured under the Foreign Person rule against an exception, similar to the US International Traffic in Arms Regulations 126.18(c) screening option.8

- The Australian Government should include a mechanism to support compliance for commercial entities’ dual-use technology activities, such as a low-risk or category-specific dual-use Australian General Licence (AUSGEL) for in-country transfers, while still enabling regulatory oversight. This would be particularly valuable for SMEs in dual-use sectors who may struggle to implement the proposed rules in their current form due to the high compliance burden.

Introduction

On 30 November 2023, Australian Deputy Prime Minister and Defence Minister Richard Marles introduced to Parliament the Defence Trade Controls Amendment Bill 2023.9 The bill has since been referred to the Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Legislation Committee, after being open for public comment for only seven days. It is expected that the Committee will release its report by 30 April, with legislation anticipated to come into effect mid-year.

The bill was introduced for two reasons. Firstly, as the explanatory memorandum for the bill summarises, “the Defence Strategic Review made clear that Australia is facing the most difficult set of strategic circumstances since the Second World War. To keep pace with these emerging challenges, it is essential that Australia has a robust protective security environment.”10 Australia’s export control system is a key element of Australia’s protective security environment, which refers to the myriad of Australian laws and policies that protect Australian technology, information, systems and technology infrastructure against compromise or unauthorised access.

The second reason for the introduction of the bill is the need for Australia to demonstrate that it has a system of export controls comparable to that of the US International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR).11 This will enable the US Congress to legislate better terms for Australian — US defence trade.12 ITAR is the US regulation that governs the export and movement of United States-origin military items, technology and services.13 However, many say that ITAR itself is outdated; it is frequently criticised for creating significant regulatory and bureaucratic barriers and preventing the sharing and co-developing of critical and emerging technologies between the United States and its allies.14

This policy brief outlines the current export control legislative framework in Australia and compares the status quo to the proposed rules. It argues that the proposed rules would bring significant benefits for Australia, most notably, in prompting the United States to provide Australia with an AUKUS export control exemption which would alleviate some of Australian industry and academia’s issues with ITAR compliance. It also acknowledges the proposed rules have shortfalls in that they would add compliance complexity to Australia’s export control system which would be a significant impediment to Australian industry and academia in the short term as they seek to implement the new requirements into their systems, policies, and processes. To ensure the proposed rules are genuinely fit for purpose and to support industry and academia through the change, the Australian Government should consider the policy options outlined below which would address key industry and academia concerns and facilitate a smooth as possible transition to the new export control framework.

Current legislation

The current Australian export control regime restricts the export of tangible items and supply of intangible equipment and technology listed on the DSGL to a place outside Australia.15 Current Australian law says that if an entity or individual proposes to export a DSGL-controlled item, a Defence Export Controls Permit is required.

Australia’s defence export control framework is built around the DSGL. The Customs (Prohibited Export) Regulations 1958 and the Defence Trade Controls Act 2012 define prohibitions and regulations by reference to the DSGL. The DSGL is a list of military and commercial goods and technologies that Australia regulates. The items, software and technologies on the list are agreed upon between the members of various international non-proliferation and export control regimes. These items either have a military use or can be used to develop weapons of mass destruction.

Part 1 of the DSGL covers defence and related goods, essentially inherently lethal goods and technologies designed or adapted for use by militaries. Part 2 of the DSGL covers dual-use goods, essentially equipment and technologies developed to meet commercial needs but might also be used in military applications or for the development or production of military systems or weapons of mass destruction.

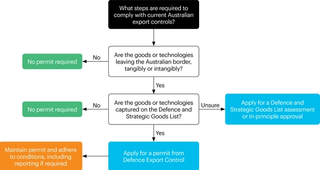

Under the current regime, there is no restriction on a person inside Australia providing controlled DSGL technology or services to another person inside Australia, regardless of that person’s nationality. Likewise, there is no extra-territorial application of Australian export control rules that requires the overseas end-user of Australian-controlled equipment to seek a DEC permit for any subsequent sale, resupply or re-export to another country. Figure 1 represents the current Australian export control requirements for Australian industry and academia.

Figure 1. Current Australian export control requirements

New legislation

The bill would create an export-licence-free environment between Australian, United States and United Kingdom persons for the supply of DSGL technology. As a result, it would remove permit requirements for supplies of DSGL technology to the United Kingdom or the United States, potentially resulting in fewer permit applications for Australian exporters overall. The current and future benefit of the Australia-US technology-licence-free environment is clear, as Australia is one of the United States’ largest defence customers and “the partnership is expected to deepen further over the coming decade, including in the area of defense industry cooperation.”16 On this basis, the proposed rule could be highly beneficial to Australian entities that would no longer need to obtain and maintain DEC supply permits where the supply of intangible technology is either going to a United States person in Australia or being sent to the United States. Australia — United Kingdom defence cooperation and collaboration would similarly benefit. It is anticipated that the proposed rules would reduce some of the Australian export control administrative burden for future technology design cooperation and collaboration on nuclear-powered submarines capability and AUKUS Pillar II collaborations. AUKUS and bilateral defence collaboration with the United States and the United Kingdom will be more efficient without the requirement to obtain a licence every time an Australian entity needs to share DSGL technical data.

The bill also creates three new criminal offences in the Defence Trade Controls Act 2012, pertaining to:

- The supply of certain DSGL Technology, as defined in the DSGL to a non‑exempt foreign person within Australia.17

- The supply of certain DSGL goods and technology, that was previously exported or supplied from Australia, from one foreign country to another foreign country, person or entity.18

- The provision of DSGL services related to Part 1 of the DSGL (Military List) to foreign persons.19

These proposed changes are substantial. The reformed controls would operate in two realms that they did not previously, being in-country (inside Australia)and extraterritorial. However, the proposed changes do come with exceptions. These exceptions would ensure a high initial threshold for engaging the new controls. The proposed offences, their exceptions and the circumstances in which industry or academia could be affected are outlined below.

The offences are broad. However, the proposed exceptions are far-reaching. The overall effect is a capture and release regulatory mechanism where a broad number of circumstances are initially captured by the offences (i.e. provision of controlled technical data to any foreign person within Australia),20 but a significant amount of the initial capture is subsequently released through the exceptions. In this case, this is done through identifying safe countries and releasing them from consideration around the offence.21

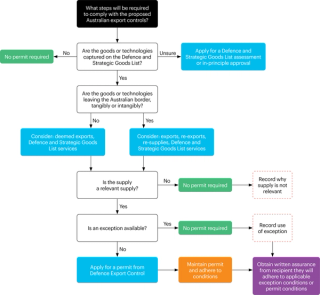

Though there are substantial exceptions available to industry and academia in the proposed bill, the everyday compliance requirements may be significantly more burdensome due to the proposed penalties. The additional workload to comply with the proposed requirements is clear when comparing current export control workflow shown in Figure 1 with the proposed workflow in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Proposed Australian export control requirements

Offence 1

The first proposed offence is for the supply of certain DSGL Technology, as defined in the DSGL (i.e. technical data such as blueprints), to a non‑exempt foreign person within Australia.22 It has the effect of requiring a permit from DEC, or an exception to apply, before the provision of controlled defence or dual-use technical data to certain foreign persons inside Australia.

The proposed exceptions include the supply or transfer of DSGL-controlled technical data to:

- A citizen or permanent resident of Australia, the United Kingdom or United States located in Australia;23

- A foreign person with a government security clearance issued by Canada, New Zealand, the United States or the United Kingdom;24

- A foreign employee who is a national of one of the Foreign Country List countries;25

- A visiting foreign person with the nationality of one of the countries on the Foreign Country List, where certain conditions are met.26

The first consideration is that this proposed offence only applies to DSGL-controlled technology — it does not apply to hardware, meaning tangible equipment, components or materials. Visual access to DSGL-controlled hardware is therefore not captured by the proposed rules unless it could be said that visual access gives a person information necessary for the “development”, “production” or “use” of a product.27

The second consideration is the definition of a foreign person provided in the bill. A “foreign person” is defined by the bill as a person who is not an Australian citizen or permanent resident of Australia.28 It does not include Australian citizens or permanent residents who hold another citizenship in addition to their Australian citizenship or permanent residency. Consequently, dual nationals are not captured by the proposed rules.

The final consideration is that 25 nationalities are treated as exempt from the offence. Third-country nationals of the United States and the United Kingdom are exempt, plus any third-country nationals from the list of 25 countries listed on the Foreign Country List.29 This further reduces the group captured under this offence substantially.

Taking into consideration the definition of “foreign person,” as well as the exceptions available, the effect is that third-country nationals in Australia who are not nationals of the 25 countries on the Foreign Country List will require a DEC permit before receiving or accessing DSGL-controlled technical data.

Offence 2

The second proposed offence is the supply of certain DSGL goods and technology that were previously exported or supplied by Australia from one foreign country to another foreign country, person or entity.30 Proposed exceptions to this include supply in the following circumstances of re-export or re-supply:

- to a citizen or permanent resident of Australia, the United Kingdom or the United States who is located in any of these countries;31

- a person with a security clearance issued by the governments of Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United States or the United Kingdom;32

- a foreign employee who is a national of a country listed on the Foreign Country List, or an Australian citizen or permanent resident, where their employer is the supplier;33 and

- certain supplies of DSGL goods and technology that are made from a foreign country that is specified in the Foreign Country List (note this is a proposed exception to be included in the resulting regulations).34

This proposed offence introduces end-use controls and extraterritoriality for DSGL-controlled technology previously exported from Australia. The purpose of this section is to ensure the current supply is regulated as a re-export or resupply, should this occur. If the earlier supply or export was not subject to permit requirements upon leaving Australia, this offence would not be relevant, as it is concerned with regulating re-exports and re-transfers of goods and technology that were previously subject to Australian export controls.

In practice, the end-user of DSGL goods and technology exported from Australia must obtain a DEC permit if they intend to send the goods or technology to another country (a third country) or person. This is called a re-export or re-supply. This only applies to re-exports to certain countries that are not exempt, i.e. countries that are not Canada, New Zealand, the United States, or the United Kingdom. It also does not apply if the original end-user is re-exporting or re-supplying to employees with nationalities on the Foreign Country List inside their own country.35

To comply with this proposed provision, Australian organisations would need to consider implementing additional contractual controls to highlight end-use requirements to their customers and make end-users/customers aware of the actions they are obliged to take if they re-export or re-supply.

Offence 3

The third offence relates to the provision of DSGL services related to Part 1 of the DSGL (Military List) to foreign persons.36 Exceptions in the bill include:

- a DSGL service provided to a citizen or permanent resident of Australia; the United Kingdom or the United States who is located in any of those countries;37

- a foreign person with a security clearance issued by the governments of Canada, New Zealand, the United States or the United Kingdom;38

- a foreign employee who is a national of a country listed on the Foreign Country List, where their employer is providing the DSGL services;39

- a DSGL service in connection with a permit issued under another section of the Defence Trade Controls Act 2012;40

- a DSGL service provided to a citizen or permanent resident of Canada or New Zealand (note this is a proposed exception to be included in the resulting regulations).41

This section creates an offence if a person inside Australia provides DSGL services to another person inside Australia, where an exception does not apply. There is an exception to this proposal where the person receiving the services is either inside Australia with a US or UK citizenship and extends to that person when the person is in the United States or the United Kingdom. There is a further exception if the recipient of the services has a security clearance from the governments of Canada, New Zealand, the United States or the United Kingdom or if the recipient is of a nationality listed in the Foreign Country List and the employee of the person providing the services. This provision does not capture services where the services have already been approved on an existing DEC permit.

Benefits

Though Australia had little choice but to develop the bill if it hoped to qualify for a US export control exemption, Australia can anticipate significant benefits to come from it. Benefits are outlined below.

If Congress certifies that Australia’s export control regime is comparable to the United States regime, Australia will receive a US export control exemption. This would make bilateral defence and dual-use technology trade faster and less complex by removing the standard export control regulatory requirements and approval process which takes between one and six months.

The proposed rules contribute to a stronger protective security environment for Australian sovereign technologies by giving legal justification to conduct thorough risk analysis on defence and advanced technology collaborators from foreign countries.

An export control exemption could alleviate many of the complaints that Australian industry and academia have about defence technology trade and collaboration with US industry. For example, it will remove much of the time and effort involved in applying for US export authorisations as an Australian company. The authorisation development process is a pain point for Australian companies that spend months corralling internal stakeholders, contractors, and subcontractors to provide information and complete documentation before the authorisation application can be submitted. However, it is unclear if the exemption will remove the concern Australian companies have with so-called export contamination, also known as “ITAR taint.” As explained in a previous United States Studies Centre report, ITAR taint refers to:

“The use of controlled US knowledge at the research and development stage that applies to a product or service forever, even if that product is predominantly ally-developed. This US input then ‘sticks’ to defence goods and services developed in collaboration with allies or partners, complicating their re-export by these collaborators even when these articles are predominantly allied-made. The result is that, under present interpretations and applications of export control law, anything that might subsequently result from this collaboration is ‘tainted’ by US design input, preventing all future uses, retransfers or even internal movement within a country’s own industrial base or supply chain network without permission from the State Department. This is particularly consequential given the absence of any materiality criteria in the definition of a defence article in US law, and the universal application of that definition.”42

The proposed rules also allow for the Australian legal system to vet and approve the foreign persons and entities that get access to sovereign defence and dual-use technologies not just on export, but also when foreign entities wish to access the technology in Australia. In doing so, the proposed rules contribute to a stronger protective security environment for Australian sovereign technologies by giving legal justification to conduct thorough risk analysis on defence and advanced technology collaborators from foreign countries.

Shortfalls

Crucially, the bill will make export control compliance even more onerous for Australian defence and dual-use industry and academia. Though large defence companies may have the resources to handle the additional compliance burden, it may disincentivise innovative dual-use companies from working with Defence and encourage small sovereign defence companies to diversify away from the defence market.43 It will also introduce new restrictions on collaboration for Australian research institutions that could extend to non-defence projects. This was outlined by the Academy of Science and the Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering in their joint submission to the exposure draft of the bill:

“Australia on its own is not globally competitive in many of the [non-military] areas on the Defence and Strategic Goods List (DSGL) (e.g. advanced materials, electronics, sensors, photonics, lasers, navigation, and aerospace), and relies on partnerships to gain access to knowledge, technology and capability. That means that intentionally or unintentionally limiting collaboration with key partners and individuals would result in insufficient homegrown know-how for us to benefit from the quantum of expertise we need.”44

This could have the effect of stalling or disincentivising Australian international collaboration, impacting Australia’s ability to access leading research. In their response to the bill, Universities Australia noted their concern as well.

“Universities are concerned that the bill, as drafted, could place at risk our sector’s ability to engage in collaborative research with non-AUKUS partner nations. This is not in anyone’s interest. The amount of detail that is deferred to subordinate legislation, in particular around the application of exemptions, is also a significant issue. Our researchers are working right now with their international peers to fight climate change, develop vaccines and drive innovations to help us grow and prosper. This work must continue. We are committed to supporting the government to deliver AUKUS, but it must not come at the expense of other important research projects with existing and future international research partners.”

Essentially, Australia’s academic sector is concerned about the current language of the proposed rules. Ultimately the concern is that the proposed rules may cause missed opportunities for Australian researchers to work with leading international researchers on critical defence and advanced technology research.45

Policy options

To address stakeholder concerns and facilitate the implementation of the bill, the Australian Department of Defence should consider modifications to the proposed language, as well as subordinate legislation.

1. A mechanism which covers in-country transfers to a secondary Foreign Country List (which could be inclusive of countries with nascent defence capability collaboration relationships, like India and South Korea).

Such a mechanism would need to allow Defence Export Controls (DEC), as the regulator of Australian export controls, to switch it on or off for certain projects, programs, or activities. This is to take into consideration the possibility of changing geopolitical circumstances.

While this would address industry and academia concerns best if it was included as a modification to the current language of the bill, it could also be effective post-enactment as a policy mechanism.

If it were a policy mechanism established by DEC, there could be additional controls placed on the use of the mechanism, including that it must be in furtherance of a current defence project or defence contract and can only be utilised up to a certain classification.

2. An update to the current bill language to include a mechanism aimed at universities to support compliance clarity for low TRL research collaborations. This mechanism could take a few different forms.

One example is an extension of the basic research exception for universities when operating at TRL 1-2 levels, with requirements for a permit only triggering if a project makes it past TRL2. This would give universities confidence in lower TRL collaborations by providing a definitive point at which export controls come online for their research activities.

In addition, post-enactment, DEC could consider providing more resources and support to academia to help clarify the intended use of the basic research exception. This would support industry with a better understanding and also support DEC in understanding whether the exception as currently framed is fit for purpose.

3. The ability for organisations to “screen” their own permanent employees captured by the Foreign Person rule against an exception (like the US ITAR 126.18(c) (2) screening option).

As stated by the Australian Industry Group in its submission to the Defence Trade Controls Amendment Bill 2023, “Companies face challenges if similar ITAR 126.18(c)(2) exemption provisions are not implemented.”46 This policy option would mean that instead of requiring Australian industry and academia to apply for a permit when an employee of theirs is a foreign person of a country not listed on the Foreign Country List, DEC could consider a self-screen option.

To reduce risk, this could be limited to certain security classifications of services and technology, proscribe specific services or technology that does not apply to using DSGL nomenclature or refer to the Department of Industry, Science and Resources published List of Critical Technologies in the National Interest.47 If implemented, DEC should co-develop supporting resources for industry to use to guide the development of their internal policies and procedures regarding self-screening, including examples of how it can be incorporated within common Human Resources practices.

This may reduce the volume of permit applications DEC would need to assess, focusing effort on higher sensitivity areas which could include nuclear materials and technologies, electronic warfare, autonomous systems, and submarine technologies.

4. A mechanism to support streamlined compliance for commercial entities’ dual-use technology activities, such as a low-risk or category-specific dual-use Australian General Licence (AUSGEL) for in-country transfers.

This would enable Australian entities designing, researching, manufacturing or developing inherently commercial technologies to apply for a project, activity, facility or program AUSGEL if they meet eligibility criteria for that AUSGEL. The eligibility criteria could include a list of eligible DSGL Part 2 categories, eligible purposes (i.e. the activities that the permit is required for) and countries of nationality that it does/does not apply to.

If recommendation 3 is adopted, recommendation 4 may not be considered necessary as recommendation 3 will already alleviate some of the compliance burden on dual-use entities by allowing them to self-screen their employees for risk of diversion rather than obtaining a permit for Foreign person employees where their country of nationality is not listed on the Foreign Country List.

Affected industry and academic stakeholders will require substantial support when these changes come online. To ensure a smooth transition, affected stakeholders would benefit from the ability to access swift support, from a knowledgeable and authoritative source with the capacity to provide solutions.48

The bill has been criticised by some for deferring significant details and decisions to subordinate legislation. However, this provides an opportunity for Australian industry and academia to shape and influence the makeup of the subordinate legislation. This is exactly what is occurring right now, with Defence forming an academia-focused working group and an industry-focused working group to support the implementation of the bill. Industry and academia should take this opportunity to share their expert insights and challenges with Defence and help co-design subordinate legislation in a way that addresses their issues.

Conclusion

On balance, the bill will benefit Australia by making defence trade and technology collaboration with the United States, faster, less administratively burdensome and overall more efficient, including in relation to AUKUS. However, the bill undoubtedly involves concessions Australia must make to streamline defence trade with the United States, which have attracted heavy criticism.

Though it is a critically important aspect of why this bill was introduced, qualification for a US ITAR exemption is not the only benefit that its implementation may bring to Australia. The proposed rules would also modernise Australian export controls in a way that makes them fit for purpose for the current Australian strategic environment by providing the legal basis upon which Australian industry, academia and government can mitigate the risk of foreign industrial, academic and technology espionage. The bill enables the Australian technology research and development ecosystem to be on the front foot when it comes to protecting critical and sensitive Australian technology from foreign persons who may not have Australia’s best interests at heart.

This research was supported by the US Department of State.

.jpg?rect=0,80,3000,1989&fp-x=0.5&fp-y=0.44772296905517583&w=320&h=212&fit=crop&crop=focalpoint&auto=format)