Executive summary

- South Korea is as important to Australia’s interests as many of the Indo-Pacific’s larger states. But Australian policy documents tend to neglect the pivotal role that non-great powers like South Korea may play in the future of the Indo-Pacific.

- Drawing on the literature on alternative futures, this report canvasses four plausible strategic futures to the 2040s: Unified Korea, Collapsed Korea, Stalled Korea and Techno Korea. These alternative futures would result in very different approaches to defence spending, capability acquisitions and nuclear deterrence. Depending on which strategic future comes to pass, South Korea could have significant implications for the Indo-Pacific’s multipolar balance of power and cooperation with regional allies and partners, including the United States and Australia.

- While a materially and militarily Stalled Korea that is unable to overcome demographic and economic stagnation could be a source of instability in the multipolar regional order of the 2040s, a Techno Korea harnessing the full industrial and technological potential of a global and entrepreneurial economy could be a formidable major power.

- For South Korea’s US ally and strategic partners like Australia, contributing to the realisation of a Techno Korea, or even a Unified Korea, and averting a Stalled Korea or Collapsed Korea is an investment in upholding a favourable regional balance of power.

Introduction

That the future of the Indo-Pacific region will be multipolar has almost become an article of faith in Australian policy discourse. This assumption rejects the idea of a regional order dominated by US-China competition, that prevails in Washington and Beijing, and instead gives agency to other states to shape the region’s future. While Australian debates have hitherto focused on ‘great’ and ‘major’ powers, the pivotal role that non-great powers, like the Republic of Korea (hereafter ROK or South Korea), might play in shaping the regional balance of power in the coming decades is missing from the Australian foreign and security policy paradigm.

While Australian debates have hitherto focused on ‘great’ and ‘major’ powers, the pivotal role that non-great powers, like the Republic of Korea, might play in shaping the regional balance of power in the coming decades is missing from the Australian foreign and security policy paradigm.

This report examines the possible trajectories of South Korea’s national power out to the 2040s. It specifically focuses on the 2040s as the timeframe in which economic, strategic and demographic trends will have transformed the distribution of power and Australia’s relations within the Indo-Pacific.1 The report proceeds as follows. First, it introduces South Korea’s underappreciated position in a multipolar regional order. Second, it discusses South Korea’s varying conceptions of multipolarity to date. Third, it considers plausible strategic futures for how South Korea will develop by 2040, especially what it calls the “Stalled Korea” and “Techno Korea” futures. Fourth, it examines how these futures might affect key defence policy areas, including defence spending, capability acquisitions and nuclear deterrence. This report concludes by discussing the implications for South Korea’s place in the complex Indo-Pacific multipolarity of the coming decades.

1. South Korean power and multipolarity

The nature of Indo-Pacific multipolarity as articulated in successive Australian policy documents has tended to limit its focus to the great powers such as the United States and China, as well as major powers such as Japan, India, and Indonesia. For example, the Julia Gillard government in its 2012 Australia in the Asian Century White Paper identified the “major powers” of the coming decades as “China, Japan, Indonesia, India and the United States.”2 The Scott Morrison government’s 2020 Defence Strategic Update similarly emphasised a desire to prioritise “partners whose active roles in the region will be vital to regional security and stability, including Japan, India and Indonesia.”3

Despite its relative absence from recent Australian strategic documents, South Korea is as important, if not more so, to Australia’s interests as many of the other large Indo-Pacific states regularly cited by Australian officials as major powers in a multipolar regional order. South Korea was Australia’s fourth-largest trading partner in 2022 (A$81.8 billion), three times larger than with Indonesia.4 The bilateral economic relationship will likely continue to grow thanks to the 2021 Australia-ROK Comprehensive Strategic Partnership, which will facilitate deeper cooperation on renewable energy, critical minerals, secure supply chains, and emerging technologies.5

The Lowy Institute’s Asia Power Index consistently shows that South Korea’s military capability ranks higher than Japan and Australia, and more than doubles that of Indonesia.6 On most of the sub-indices, such as defence spending, size of armed forces, military posture, weapons and platforms, and signature capabilities, South Korea ranks in the top five and is likely to do so for the foreseeable future, with year-on-year defence budget increases of over seven per cent.7 These are favourable trends from an Australian perspective, given the two countries’ growing strategic alignment, defence industrial cooperation and range of combined military exercises.8 To borrow an economic analogy, while South Korea’s net security capacity to contribute to the regional balance of power may currently be low due to its primary focus on the North Korean threat, its gross security capacity is high due to its national mobilisation and defence build-up.

2. South Korean conceptions of multipolarity

South Korean experts nonetheless tend to interpret multipolarity through two distinct geographic lenses that sit at odds with Australian thinking about multipolarity.9 The first is through a classical Northeast Asian lens, in which Korea’s agency is diminished or constrained by the fact that it is surrounded by great powers. In this sense, South Korean leaders do not consider their country to be an independent pole in a multipolar regional order, either now or in the future.10 Instead, Seoul’s priorities have been the pursuit of relative autonomy and the preservation of national sovereignty within shifting great power dynamics.11 This peninsular-oriented mindset, which privileges South Korea’s immediate strategic neighbourhood over wider regional and global power dynamics, continues to manifest in mainstream policy discourse, with international crises largely viewed through the prism of the North Korean threat.12

The second lens for South Korean thinking about multipolarity is at the global level. In this view, South Korean progressives aspire to escape from US-China superpower rivalry by emphasising the importance of, and cooperation with, regional blocs such as the European Union and Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), as well as with countries of the so-called ‘Global South’, as a means to enhance South Korea’s strategic autonomy.13 South Korean conservatives, meanwhile, talk about multipolarity at the global level mostly through a global governance, rather than a strategic, prism. This view is currently expressed in the Yoon administration’s self-description as a “global pivotal state” able to play a role commensurate with its growing power in international institutions and regimes, but as a complement to, rather than a replacement for, the ROK-US alliance.14

Seoul’s priorities have been the pursuit of autonomy and preservation of sovereignty within shifting great power dynamics.

It is between these two conceptions of multipolarity—Northeast Asia and the global level—that South Korea’s national power and strategic capacity may enjoy a Goldilocks status. Scholars have developed new theories that incorporate the security choices of middle powers, such as South Korea, into great power transitions as either pivotal states in their own right or as part of multilateral coalitions.15 Most recently, the Yoon Suk Yeol administration committed to deploying its national power in a regional context by enhancing strategic partnerships with like-minded regional powers and fellow US allies.

In short, South Korean leaders have rarely thought about their own country as a major power in a multipolar regional order, but they have quietly laid the foundations for becoming one. For example, South Korea’s 2022 Indo-Pacific Strategy clearly recognises the need to proactively contribute to Indo-Pacific peace and stability.16 The Yoon administration is also pursuing security efforts like the Korea-ASEAN Solidarity Initiative, which aims to increase security cooperation with Southeast Asia, and the ROK-Pacific Islands Forum Summit Action Plan, which includes capacity-building efforts in areas such as maritime security.17 These proposals encompassing security issues go beyond the primarily trade-focused regional efforts of previous administrations.

The relationship between growing power, rising status expectations and South Korea’s place in a multipolar order is best illustrated by its defence industrial ambitions. Initially, South Korea’s defence industrial resilience was closely linked to the sustainment of a perpetual war footing against North Korea since the end of the Korean War. The maintenance of ‘hot’ production lines to keep up with domestic orders for the ROK military has also distinguished South Korea from the post-Cold War peacetime defence industrial bases of most US allies.18 Today, these unique characteristics have paved the way for South Korea’s emergence as the world’s eighth-largest arms exporter.19 In the face of Russian and Chinese military coercion, a growing number of non-great powers have turned to South Korean firms to supply defence capabilities in a market historically dominated by great powers.20 Looking ahead, the Yoon administration views defence exports as part of a “virtuous cycle” that reinforces South Korea’s own military capabilities through technological innovation.21 An existential threat driving the quest for self-reliance and industrial resilience that is accelerated through exports has been one of the hallmarks of South Korea’s modern prosperity. The next section turns to whether this model can be sustained in the coming decades.

3. South Korea’s plausible strategic futures

Scholars of alternative futures have extensively researched how South Korea, and the Korean Peninsula more broadly, may develop over the next 20 to 50 years.22 These are comprehensive national assessments that include social, economic, political, technological and environmental change to imagine alternative futures.23 A straight-line extrapolation into the future from today would assume a continuation of the status quo, with South Korea as Asia’s fourth-largest economy and military. But holding onto this position will not be easy. Leading economists project that South Korea’s economic growth rate will have almost halved to between 1.4 and 1.6 per cent by 2040 due to a shrinking workforce.24 Militarily, holding onto fourth place will also be difficult as countries like Indonesia and Vietnam start converting their rising economic affluence into military armaments.25

The ideal case scenario by 2040 would be the rise of a peaceful and prosperous unified Korea.26 This could fundamentally change the Indo-Pacific order in a manner comparable to German unification in Europe.27 Korean unification would produce a combined population of almost 80 million people with newfound synergies between South Korean capital and innovation and North Korean labour and resources. This unified Korea could be the world’s eighth-largest economy and a military powerhouse.28 It would also be a nuclear weapons power or at least a nuclear-threshold state. South Korea already possesses most of the requisite scientific and military expertise, including civil nuclear energy and weapons delivery systems, and this would be bolstered by the absorption of North Korea’s nuclear scientists, even if the regime’s nuclear weapons stockpile was dismantled.

However, the security posture of a unified Korea could vary widely depending upon the manner of unification, and the state of US-China-Russia trilateral dynamics.29 Its security posture could take many forms, including the 1990s German model of military restraint, a Swiss model of armed neutrality, or a Cold War Finlandisation of constrained sovereignty, and more.30 In terms of behaviour, a unified Korea could become a power maximiser for a US-led alliance coalition against China, bandwagon with a rising China, join a third bloc of non-aligned states, or seek armed neutrality. The possibilities and implications associated with each would be wide-ranging.

At the other end of the spectrum would be the end of South Korea as a middle power. This might involve a recurrence of South Korea’s 1997 economic crisis, in which the economy and currency almost collapsed, major conglomerates went bankrupt, unemployment tripled and the country had to request a bailout package from the International Monetary Fund.31 Such status decline could also be sparked by geostrategic developments, such as a second Korean War or a limited nuclear exchange on the Korean Peninsula. In this scenario, the question of South Korea’s strategic weight in a multipolar Indo-Pacific would become less relevant.

3.1. Stalled Korea and Techno Korea

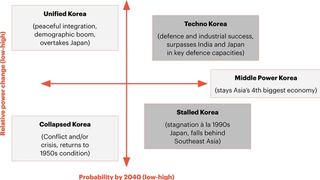

Figure 1. South Korea’s plausible strategic futures in 2040

In contrast to the status quo, unification and collapse scenarios, there are several alternative more plausible futures with less significant consequences for Korea’s national power. These possible futures are illustrated in Figure 1, measured against their probability and expected change in South Korea’s relative power.32 The first is what might be called ‘Stalled Korea.’ This would be similar to Japan’s “lost decade” in the 1990s or the economic stagnation that has recently afflicted Argentina.33 In fact, many of the economic and demographic indicators by 2040 are ominous. For example, the US National Intelligence Council predicts that South Korea will “face constraints on economic growth” as the world’s fastest ageing population, losing 23 per cent of its working-age population (age 15-64) by 2040.34 An ageing population would see a drop in workforce productivity, research innovation, new business start-ups and investment. This would likely see South Korea’s relative power in a regional context declining, with Seoul devoting ever larger proportions of its budget to social welfare rather than defence capacity.

The second future could be a thriving ‘Techno Korea’ that leverages its technological and innovation strengths into a stronger and more resilient country. It is possible to envision that the next three South Korean presidents to 2040 may harness high-tech industries to make South Korea one of the world’s top economies and military powerhouses, even without the benefits of unification.35 South Korea could achieve this by becoming a post-industrial economy using emerging technologies such as robotics, artificial intelligence and biotechnology to not only offset the negative effects of demographic decline but also to make population size an irrelevant input to national power. Techno Korea would be able to preserve or potentially even increase its current power advantage over today’s rising Southeast Asian countries whose continued economic growth heavily depends on their large and young workforces.

4. South Korea’s defence policy futures

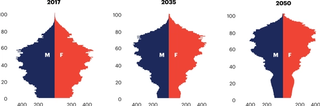

These alternative futures would transform South Korea’s strategic profile. For example, on military manpower, Figure 2 illustrates how South Korea is fast approaching a youth demographic squeeze in the next decade. South Korea’s current mandatory military service cohort of 20-year-old men, which currently accounts for about 80 per cent of Korea’s total defence personnel, is forecast to halve from 333,000 in 2020 to 143,000 in 2040. These trends are already impacting South Korean force structure today. Since 2020, the ROK Ministry of National Defense (MND) has disbanded the 8th Army Corps and merged the 5th and 6th Army Corps as part of its Defense Reform 2.0 plan due to declining troop numbers.36 This trend can only be reversed with unprecedented policy changes such as mass immigration or all-gender conscription, ideas which have been raised by lawmakers but are currently unlikely to be taken up due to political opposition, who have mostly called for an all-volunteer or a technology-driven military force instead.37 Stalled Korea and Techno Korea would both face a similar demographic constraint, not to mention the associated decline in government revenue from a smaller working-age population in 2040.

Figure 2. The ROK’s changing demographic pyramid: 2017, 2035 and 2050 (left: males; right: females | x axis: population in thousands; y axis: age bracket)38

4.1. Defence spending forecast

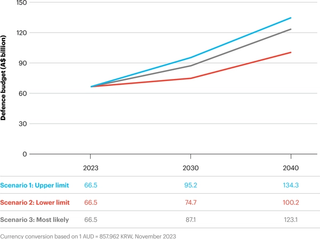

All other things being equal, these alternative futures would nonetheless lead to different approaches to defence spending, capability acquisitions and nuclear deterrence. On defence spending, Figure 3 shows the most likely forecast by 2040 will be 105.6 trillion KRW (approximately A$123 billion). While gross domestic product (GDP) forecasts obviously vary widely to 2040, this would amount to a defence budget of approximately 2.8 per cent of GDP, roughly similar to today’s 2.7 per cent of GDP.39 Total defence spending would be approximately double what it is today, at 52 trillion KRW. By contrast, the Stalled Korea scenario would see the defence budget 19 per cent lower, at 86 trillion KRW (A$100 billion). In the Techno Korea scenario, the higher limit would be 9 per cent higher at 115.2 trillion KRW (A$134 billion), with ample scope for even higher levels of spending. The three ranges are shown in Figure 3 below. Put simply, the gap in annual defence spending between the two future scenarios could be roughly A$34 billion.

Figure 3. ROK long-term defence budget outlook by scenario (A$ billion)40

4.2 Capability acquisition forecast

On capability acquisitions, the ROK MND currently allocates about 16-17 trillion KRW ($18-20 billion AUD) each year towards capability acquisitions, or what the MND calls “force enhancement projects”, which is roughly a third of the defence budget. Stalled Korea would spend about $30-35 billion AUD on capability acquisitions while Techno Korea would spend closer to $45-50 billion AUD. The A$15 billion difference between the two figures is the difference between many of the ROK MND’s investment priorities being funded or neglected. The ROK MND’s Basic Plan on Defense Innovation 4.0 and the Defense Acquisition Program Administration’s (DAPA) 2022-2036 Core Technology Plan heavily rely on technological solutions and unmanned systems.41 The ROK Army’s ‘Transformative Innovation of Ground forces Enhanced by the 4th industrial Revolution technology’ (TIGER 4.0) similarly focuses on shifting capability investments towards drones, reconnaissance robots and manned-unmanned platforms.42 Furthermore, there would be greater political pressure to reduce personnel-heavy capabilities for which the different ROK armed services currently advocate, and to instead find technology solutions to South Korea’s operational requirements.43 For example, the 50,000-tonne ROK CVX-class aircraft carrier under consideration for construction by 2033 is only likely to require a crew of 440 compared to over 1000 on similarly-sized ships in other countries, making them only marginally more crewed than the existing Dokdo-class amphibious assault ships.44

4.3 Nuclear deterrence forecast

Absent a dramatic change in North Korea’s nuclear capabilities and threats, it is reasonable to assume that South Korea’s nuclear debate will cross new thresholds by 2040. The ROK-US alliance has recently made important strides to reassure South Korea about the US extended nuclear deterrence commitment to South Korea’s security in the face of an escalating North Korean nuclear arsenal and coercion, such as establishing the bilateral Nuclear Consultative Group (NCG) and visible visits by US nuclear strategic assets to the Korean Peninsula. Yet, to date, the allies have found little if any success in denuclearising or disarming North Korea.45 Pyongyang’s continuing development of the means to hold the US homeland at risk poses a long-term challenge to the credibility of extended nuclear deterrence. These unfavourable trends will only increase pressure on Seoul to consider tougher deterrence measures in the coming years. Without addressing the central problems of North Korea’s possession of nuclear weapons and secure delivery systems or the concomitant erosion of credible US security assurances, South Korea is likely to re-think its nuclear deterrence strategy. In a March 2021 assessment of future scenarios, the US National Intelligence Council predicted that, in a worst-case outcome in 2040, “the United States attempted to preserve ties to remaining allies in the region, but Japan and South Korea pursued increasingly independent military modernization programs and even their own nuclear weapons programs, in part out of concern about the reliability of the US security umbrella against China and North Korea.”46

Stalled Korea would be dependent on the United States, which in turn would reduce its risk appetite for indigenous nuclear armament.

The nature of South Korean power will affect whether it can successfully pursue an independent nuclear option. For example, Stalled Korea would likely become more dependent on the United States, which in turn would reduce its risk appetite for indigenous nuclear armament if this would risk firm alliance commitments. The pursuit of an independent strategic deterrent and greater security autonomy could be discarded given the financial, technical and diplomatic challenges. By contrast, Techno Korea would have put in place all the requisite conditions for a nuclear weapons capability by 2040, at the very least leaving open the option of an independent strategic deterrent if circumstances required it.

5. Implications

The plausible strategic futures canvassed in this report suggest that greater caution is warranted in predicting the future distribution of power in a multipolar Indo-Pacific. It is not just the trajectory of the United States or China that will shape the regional balance of power but also the internal trends across a larger number of major and middle powers. The different composition of national power in the Stalled Korea and Techno Korea scenarios outlined above would have significantly different implications for how South Korea affects the regional balance of power.

In short, a materially and militarily Stalled Korea, unable to overcome demographic and economic stagnation, would be a weak contributor in upholding a favourable balance of power in the multipolar regional order of the 2040s. It could be closing military bases across the country due to a shortfall of troops, much as it is currently closing kindergartens in the countryside today. Its military would be overstretched just managing the North Korean threat whilst trying to preserve its maritime sovereignty against Chinese, Russian and North Korean incursions.

For South Korea’s US ally and strategic partners like Australia, contributing to the realisation of a Techno Korea or even a Unified Korea is an investment in upholding a favourable regional balance of power.

By contrast, a Techno Korea harnessing the full industrial and technological potential of a global and entrepreneurial economy could overcome the looming demographic crisis and pull far ahead of potential regional rivals. This would be a South Korea that leads the world in military modernisation by devoting large proportions of its defence budget to technology research and development. Its arms exports alone would be game-changers for many regional militaries as they make generational leaps from Cold War-era platforms to state-of-the-art South Korean fighter jets, submarines and missiles.

For South Korea’s US ally and strategic partners like Australia, contributing to the realisation of a Techno Korea or even a Unified Korea, and averting a Stalled Korea or Collapse Korea, is an investment in upholding a favourable regional balance of power. While much of the outcome will ultimately depend on South Korea’s own leadership and national efforts, these partners can help by preserving the necessary conditions for national power discussed in this report, including demographic vitality, economic and technological innovation, and free trade and stable investments.

Conclusion

Forecasting the contours of multipolarity out to 2040 is a fraught exercise. Whether the Indo-Pacific region becomes truly multipolar in the next two decades depends on whether the United States and China can preserve their preponderance of material power over the rest of the region. If they can, then the region will be bipolar for all intents and purposes. If they cannot, then the region will transition to a new form of multipolarity in which power is distributed across several states and various sectors. The scope for middle powers like South Korea and Australia to become independent poles, as in a classical understanding of multipolarity, will remain limited. Nonetheless, they might be strong enough to defend their sovereignty, pivotal to strategic contests and exert collective influence that could offer an alternative to US-China domination.

But strong, rather than just big, countries may be best placed to preserve their sovereignty and contribute to balancing dynamics in the coming decades. The key determinants of whether South Korea is a stronger or weaker country in 2040 will be its demographic vitality, economic prosperity and technological innovation.47 Without all three, military capacity will be ephemeral and resilience fleeting. South Korea represents an interesting case study of how power and resilience need to be considered in assessing the regional balance of power. Looking out to the 2040s, South Korea may prove more powerful and resilient than imagined.

.jpg?rect=0,80,3000,1989&fp-x=0.5&fp-y=0.44772296905517583&w=320&h=212&fit=crop&crop=focalpoint&auto=format)