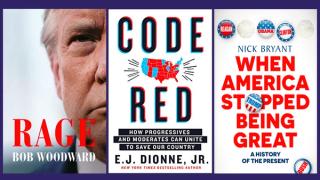

Bob Woodward’s new book, Rage, is based on 18 taped interviews with US President Donald Trump, totalling nine hours and 41 minutes. In one of them, the author talks in terms of writing the first draft of history.

While occasionally mired in controversy, Woodward normally achieves much with his books. It can be said that All the President’s Men and The Final Days (with Carl Bernstein) represent definitive conclusions.

Woodward has won two Pulitzer prizes for reporting on Watergate and 9/11. As an associate editor of The Washington Post, he has assumed the journalistic proportions of the Smithsonian Institution, as a Washington point of reference, recording the ebb and flow of the Republic’s affairs.

Trump’s intended charm offensive appears to have been his undoing, causing at least one commentator to observe that the President had become his own whistleblower. He is disarmingly open about the impact of COVID-19.

Woodward’s previous book, Fear, was a scathing indictment of the chaos of the early Trump administration. This time around, as with a number of his predecessors, Trump agreed to be interviewed by Woodward.

Judging by the tapes of the interviews, the US President approached Woodward in a manner similar to a devoted fan catching first sight of Mick Jagger backstage at a Rolling Stones concert.

Trump’s intended charm offensive appears to have been his undoing, causing at least one commentator to observe that the President had become his own whistleblower. He is disarmingly open about the impact of COVID-19.

Unfortunately, he is less than candid with the American people on the serious public health challenge that the virus presents. He also boasts to Woodward about a new American weapons system, one apparently unknown to adversaries.

Trump is keen to please, presenting Woodward with gifts and mementos that underline his foreign policy forays, especially involving North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un.

Woodward not only interviews, he offers advice. Trump listens, but rarely does this President take advice kindly. His Cabinet understands that.

Indeed, in a searching interview with Woodward, Stephen Colbert observes that it is a pity Trump’s flaws prevent an able administration doing better. This is born out eloquently by an observation from former defense secretary, James Mattis: “When I was basically directed to do something that I thought went beyond stupid to felony stupid, strategically jeopardising our place in the world and everything else, that’s when I quit.”

Director of National Intelligence, Dan Coats, suffered other difficulties. A conservative Christian and dedicated Republican senator, Coats fell out with Trump and tried to resign, unsuccessfully.

Code Red argues thoughtfully for moderate and progressive Democrats to focus on their common beliefs and reach out to liberal Republicans, especially on core issues such as healthcare and living wages.

But at the Aspen Security Conference of July 2019, Coats committed a mortal sin: celebrity. While being interviewed on stage by Andrea Mitchell of NBC, he was told that Trump had agreed to a White House meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin. Coats was stunned and blurted out: “That’s going to be special.” Sitting in the audience, I laughed along with everyone else, including Coats, thinking he would not survive long. Ultimately, he learned of his sacking from The New York Times. As usual, Woodward has had remarkable access to the players in Washington DC. He endeavours to be fair, but he concludes that Trump is not right for the job.

A similar conclusion is reached by EJ Dionne, a columnist with the Washington Post. His book, Code Red, argues thoughtfully for moderate and progressive Democrats to focus on their common beliefs and reach out to liberal Republicans, especially on core issues such as healthcare and living wages.

The effective co-operation between the Biden and Sanders wings of the Democratic Party, and the emergence of the Lincoln Project by dissident Republicans, shows that some understand this common sense notion. It was Gore Vidal who made the case that the US ceased being great when it became a debtor nation. Most would agree that this occurred systemically during the Reagan administration, when the US federal deficit metastasised.

The US had been the ‘‘indispensable country’’, to borrow Madeleine Albright’s memorable expression, since the Great War. In 1915, the Angophilic JP Morgan and a group of New York bankers marshalled a loan of some $US500m for the Anglo-French allies to enable them to maintain their war effort.

Nick Bryant’s book, When America Stopped Being Great, is an impressive endeavour to identify just when the US arrived at the threshold of decline. He comes close. Bryant is a BBC correspondent in Washington DC, having previously worked in Australia among other destinations. He is a first class journalist, but he is also possessed of undeniable skills as an historian, having earned a PhD in American politics from Oxford. He writes with confidence because he has a deep understanding of American political culture.

Bryant begins his journey in Los Angeles in 1984, the year of the Olympics. Reagan is president and Vietnam, Watergate and the Iran hostage crisis are apparently behind the US.

Reagan’s campaign slogan that year perhaps sums it up best: “It is morning in America.” Of course, Reagan had also routinely used the expression ‘‘Make America great again’’ in 1980, a rhetorical device Bill Clinton reused in 1992.

Trump’s unforeseen election in 2016 showed the world the point that America had reached. November 3, 2020, will be a glowing indicator of its future.

At times, Bryant writes with an archness worthy of Vidal. A good example is his discussion of the cannibalism in Congress after the impeachment of Clinton. Speaker Newt Gingrich lost his office when the Republicans suffered a setback in the 1998 midterms. Oh, and he also admitted to an extramarital affair himself.

Then Gringrich’s replacement, Bob Livingston, also resigned after an extramarital affair was exposed. “ ... he was impaled on his own penis,’’ Bryant writes. “A grotesque irony was that the speakership then passed to Dennis Hastert, a former teacher considered back then to be irreproachable, who was later exposed as a child molester.”

On Trump’s election to the White House, Bryant quotes the insightful Alexis de Tocqueville, who wrote Democracy in America in 1836. De Tocqueville argued that the French Revolution of 1789 was inevitable but unforeseen. However, Bryant traces the arrival of Trump back to Senator Barry Goldwater’s insurgent campaign for president in 1964, which brought Reagan to the national political arena. Reagan delivered ‘‘The Speech’’, ‘‘A Time for Choosing’’, arguing persuasively in support of Goldwater.

Reagan is seen by Bryant as the godfather to polarisation in American politics. Running for president in 1980, Reagan chose to open his campaign in Neshoba, Mississippi, deliberately building on the success of Richard Nixon’s ‘‘Southern Strategy’’. Neshoba was not far from where three young civil rights advocates were murdered in 1964 by Klansmen.

Reagan ran against Washington and against government itself, which had a certain irony to it, given he was the governor of California at the time. But as president, following Jimmy Carter, Reagan revived the Imperial Presidency in style and fanfare, while delivering uplifting and optimistic speeches, centred at times on American myths. However, he was weak on the detail required by the office, once quipping, ‘‘hard work never hurt anyone, but hey, why take the risk?’’. Bryant draws much of the Trump era from the Reagan years.

However, he appears to have missed the impact of Nixon’s vice-president, Spiro Agnew, in forging ‘‘the silent majority’’, which has been sketched in undeniable detail in Republican Populist by Charles J. Holden, Zach Messitte and Jerald Podair.

These three books analyse the continuing shift in the American political. Trump’s unforeseen election in 2016 showed the world the point that America had reached. November 3, 2020, will be a glowing indicator of its future.

Rage by Bob Woodward (Simon and Schuster, 480pp)

When America Stopped Being Great: A History of the Present by Nick Bryant (Viking, 432pp)

Code Red: How Progressives and Moderates Can Unite to Save Our Country by EJ Dionne (Saint Martin’s Press, 272pp)